Lenvatinib versus Sorafenib as first-line treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma: A multi-institutional matched case-control study

Abstract

Background

Advanced Hepatocarcinoma (HCC) is an important health problem worldwide. Recently, the REFLECT trial demonstrated the non-inferiority of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib in I line setting, thus leading to the approval of new first-line standard of care, along with Sorafenib.

Aims and methods

With aim to evaluate the optimal choice between Sorafenib and Lenvatinib as primary treatment in clinical practice, we performed a multicentric analysis with the propensity score matching on 184 HCC patients.

Results

The median overall survival (OS) were 15.2 and 10.5 months for Lenvatinib and Sorafenib arm, respectively. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.0 and 4.5 months for Lenvatinib and Sorafenib arm, respectively. Patients treated with Lenvatinib showed a 36% reduction of death risk (p = 0.0156), a 29% reduction of progression risk (p = 0.0446), a higher response rate (p < 0.00001) and a higher disease control rate (p = 0.002). Sorafenib showed to be correlated with more hand-foot skin reaction and Lenvatinib with more hypertension and fatigue. We highlighted the prognostic role of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS), bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and eosinophils for Sorafenib. Conversely, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) resulted prognostic in Lenvatinib arm. Finally, we highlighted the positive predictive role of albumin > Normal Value (NV), ECOG > 0, NLR < 3, absence of Hepatitis C Virus positivity, and presence of portal vein thrombosis in favor of Lenvatinib arm. Eosinophil < 50 and ECOG > 0 negatively predicted the response to Sorafenib.

Conclusion

SLenvatinib showed to better perform in a real-word setting compared to Sorafenib. More researches are needed to validate the predictor factors of response to Lenvatinib rather than Sorafenib.

Key points

-

Recently, the REFLECT trial demonstrated the non-inferiority of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) I line setting, thus leading to the approval of new first-line standard of care

-

With aim to evaluate the optimal choice between Sorafenib and Lenvatinib as primary treatment in clinical practice, we performed a multicentric analysis with the propensity score matching on 184 HCC patients

-

In our analysis, Lenvatinib showed to better perform in a real-word setting compared to Sorafenib. More researches are needed to validate the predictor factors of response to Lenvatinib rather than Sorafenib

Abbreviations

-

- AEs

-

- Adverse Events

-

- AFP

-

- Alpha-fetus protein

-

- ALT

-

- Alanine aminotransferase

-

- AST

-

- Aspartate aminotransferase

-

- BCLC

-

- Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage

-

- CI

-

- Confidence Interval

-

- DCR

-

- Disease Control Rate

-

- ECOG PS

-

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

-

- EHD

-

- Extra Hepatic Disease

-

- FDA

-

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration

-

- FGF

-

- Fibroblast Growth Factor

-

- HBV

-

- Hepatitis B Virus

-

- HCC

-

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma

-

- HCV

-

- Hepatitis C Virus

-

- HFSR

-

- Hand-Foot Skin Reaction

-

- HR

-

- Hazard Ratio

-

- NLR

-

- Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio

-

- NV

-

- Normal Value

-

- OS

-

- Overall Survival

-

- PDGF

-

- Platelet-Derived Growth Factor

-

- PFS

-

- Progression-Free Survival

-

- PS

-

- Propensity Score

-

- RR

-

- Response Rate

-

- TKI

-

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor

-

- VEFG

-

- Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary malignancy of the liver and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1-3

Sorafenib is an oral multiple kinase inhibitor targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptors, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors, BRAF and KIT. It was the first systemic therapy to be approved for the treatment of unresectable HCC after having demonstrated a survival benefit in patients with advanced HCC in the first-line setting.4, 5

Despite the treatments options for advanced disease have increased, thus achieving a relatively long-term survival even for patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C, the prognosis of these patients remains unsatisfactory.6

Since the results with Sorafenib were published, multiple phase III trials have failed to demonstrate improved outcomes over Sorafenib in this setting.7-11 Recently, the REFLECT trial meets the aim to demonstrate the no inferiority of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib as first-line in advanced HCC patients.12 Additionally, Lenvatinib demonstrated a significant improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) time, and a better quality of life evaluated as time to clinically meaningful deterioration of role functioning, pain, diarrhea, nutrition and body image12: the results obtained leaded to the approval of Lenvatinib as new first-line standard of care, along with Sorafenib.13

Recently, a new class of drugs have been evaluated in the advanced HCC setting, including the first-line setting: immunotherapy. From the global, open-label phase 3 study IMbrave150, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab achieved a 42% reduction in the risk of death versus Sorafenib (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.42–0.79; p < 0.001), thus leading to the approval by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the new combination in the first-line setting advanced HCC patients.14

To date, no randomized prospective trials have demonstrated the superiority of the new combination compared to Lenvatinib, and further studies about biomarkers able to define patients likely to respond to the combination regimen instead the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) are mandatory in order to optimize treatment in this setting. For this reason, nowadays TKIs remain a main stone in the treatment of advanced HCC patients.

However, the real-word data in literature are insufficient15, 16 and the optimal choice between Sorafenib and Lenvatinib as primary treatment in clinical practice is still controversial.

With the aim to fill this gap, we performed a multicentric analysis with the propensity score matching to evaluate the real-word treatment outcomes between Sorafenib and Lenvatinib in patients with unresectable HCC.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The study population derived from prospectively collected data of patients treated with Sorafenib or Lenvatinib as first-line for advanced-stage HCC (BCLC-C) of for intermediate HCC (BCLC-B) deemed not eligible for first- or for re-treatment with surgical or loco-regional therapies. The overall cohort included Western and Eastern populations from two countries (Italy and Japan) between March 2018 and June 2020. For reduce bias derived from period selection we selected patients treated with Sorafenib or Lenvatinib in the same period. Eligible patients had HCC diagnoses confirmed histologically or confirmed clinically in accordance with international guidelines and none of them received previous systemic therapy. Common inclusion criteria for the use of Sorafenib or Lenvatinib were applied.

The present study was approved by ethics committee at each center, complied with the provisions of the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and local laws and fulfilled the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data.

The primary outcome of the study was overall survival time, defined as the time from initiation of Sorafenib or Lenvatinib treatment to the date of death or the patient's last follow-up. Follow-up ended on August 2020.

All patients were treated with Sorafenib, until Lenvatinib approval. After Lenvatinib approval, the choice between the two therapies was left to physician in-charge discretion. Lenvatinib was administered as described in the REFLECT trial thus,12 patients received 12 mg if baseline bodyweight was ≥60 kg or 8 mg if baseline bodyweight was <60 kg, given once daily orally. Sorafenib was administered as in common clinical practice, and all patients in the Sorafenib group received a starting dose of 400 mg orally twice daily.4, 5

Treatment interruptions and dose reductions allowed to manage adverse events (AEs). Hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR), diarrhea hypertension, fatigue, decreased appetite, proteinuria and hypothyroidism were the main AEs recorded and were graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.03.

STATISTICALLY ANALYSIS

Frequency tables were performed for categorical variables. Continuous variables were presented using median and range. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from start date of Sorafenib or Lenvatinib to date of death. PFS was defined as the time from start date of Sorafenib or Lenvatinib to date of progression or death or last follow-up whichever occurred first. OS and PFS were reported as median values expressed in months, with 95% confidence interval (CI). Survival curves were estimated using the product-limit method of Kaplan-Meier. The role of stratification factor was analyzed with log-rank tests. Propensity score (PS) is the conditional probability of being treated given a set of observed potential confounders. In this way all the information from a group of potential confounders is summarized into a single balancing score variable, the so-called PS. PS assures that the distribution of measured baseline covariates is maintained unchanged in both arms. Standardized difference was used as balance measure to compare the difference in means in units of the pooled standard deviation.

A MedCalc package (MedCalc® version 16.8.4) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

One hundred eighty-four consecutive patients with HCC were available for the analysis. Ninety-two patients were treated with Lenvatinib from November 2017 in Italian institutions, and from March 2018 in Japanese institutions to June 2020, and 92 patients were treated with Sorafenib from March 2016 to June 2018.

Patient characteristics for the two groups are shown in Table 1.

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib | Lenvatinib | p | Sorafenib | Lenvatinib | p | |

| n | n | n | n | |||

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Italy | 62 | 32 | 40 | 25 | ||

| Japan | 82 | 123 | 0.000036 | 52 | 67 | 0.03 |

| Age | ||||||

| <65 | 57 | 34 | 33 | 23 | ||

| >65 | 93 | 121 | 0.002 | 59 | 69 | 0.15 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 129 | 124 | 81 | 75 | ||

| Female | 21 | 31 | 0.17 | 11 | 17 | 0.30 |

| BCLC stage | ||||||

| B | 37 | 99 | 36 | 36 | ||

| C | 113 | 56 | <0.000001 | 56 | 56 | 1.00 |

| Etiology | ||||||

| HCV | 73 | 70 | 41 | 38 | ||

| HBV | 21 | 28 | 15 | 18 | ||

| Others | 56 | 57 | 0.60 | 36 | 36 | 0.85 |

| Performance status | ||||||

| 0 | 106 | 125 | 65 | 70 | ||

| 1 | 44 | 30 | 0.04 | 27 | 22 | 0.40 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | ||||||

| No | 86 | 142 | 78 | 81 | ||

| Yes | 64 | 13 | <0.000001 | 14 | 12 | 0.83 |

| Macrovascular invasion | ||||||

| No | 104 | 106 | 82 | 84 | ||

| Yes | 46 | 49 | 0.90 | 10 | 8 | 0.80 |

| Child | ||||||

| A | 139 | 150 | 85 | 87 | ||

| B | 11 | 5 | 0.12 | 7 | 5 | 0.56 |

| AFP | ||||||

| <400 | 106 | 122 | 67 | 67 | ||

| >400 | 44 | 33 | 0.11 | 25 | 25 | 1.00 |

| NLR | ||||||

| <3 | 69 | 90 | 45 | 52 | ||

| >3 | 81 | 65 | 0.007 | 47 | 40 | 0.30 |

| Eosinophils | ||||||

| <50 | 26 | 34 | 15 | 22 | ||

| >50 | 124 | 121 | 0.31 | 77 | 70 | 0.20 |

| Extrahepatic spread | ||||||

| No | 80 | 110 | 48 | 48 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 45 | 0.002 | 44 | 44 | 1.00 |

| Bilirubin | ||||||

| <NV | 97 | 127 | 68 | 74 | ||

| >NV | 53 | 23 | 0.0001 | 24 | 18 | 0.37 |

| Albumin | ||||||

| <35 | 49 | 37 | 28 | 22 | ||

| >35 | 101 | 113 | 0.15 | 64 | 70 | 0.40 |

| ALBI grade | ||||||

| 1 | 126 | 147 | 77 | 86 | ||

| 2 | 24 | 3 | 0.00002 | 13 | 6 | 0.09 |

| AST | ||||||

| <NV | 40 | 58 | 24 | 37 | ||

| >NV | 110 | 92 | 0.03 | 68 | 55 | 0.06 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | ||||||

| <NV | 20 | 5 | 9 | 5 | ||

| >NV | 130 | 145 | 0.001 | 83 | 87 | 0.40 |

- Note: Numbers written in bold correspond to the statistically significance p.

- Abbreviations: AFP, Alpha-fetus protein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HR, Hazard Ratio; HFSR, Hand-Foot Skin Reaction; NLR, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio; NV, Normal Value; OS, Overall Survival.

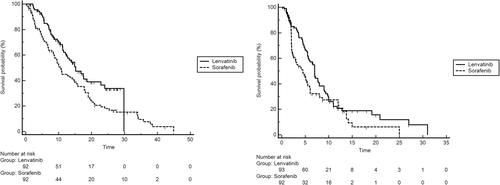

Median OS was 15.2 (95% CI: 12.0–29.8) for patients receiving Lenvatinib, and 10.5 (95% CI: 8.6–45.0) for patients treated with Sorafenib (Figure 1a). The result from univariate unweighted Cox regression model showed 36% reduction of death risk for patients on Lenvatinib (95%CI: 0.45–0.91; p = 0.0156), compared with patients on Sorafenib.

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS in Sorafenib and Lenvatinib cohorts (a), and Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS in Sorafenib and Lenvatinib cohorts (b). Abbreviations: OS, Overall Survival; PFS, Progression-Free Survival

Following adjustment for prognostic clinical covariates normally know in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (BCLC stage, performance status, portal vein thrombosis, macrovascular invasion, child pugh, alpha-fetus protein [AFP], Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio [NLR], ALBI grade and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) and unbalance basal patients characteristic (Country of origin), after propensity score matching analysis, multivariate analysis confirmed Lenvatinib's treatment (HR 0.57; 95% CI: 0.43–0.77; p = 0.0011) as independent favorable prognostic factors for OS.

Median PFS was 7.0 (95% CI: 5.6–29.8) for patients receiving Lenvatinib, and 4.5 (95% CI: 2.6–25.0) for patients treated with Sorafenib (Figure 1b). The result from univariate unweighted Cox regression model showed 29% reduction of progression risk for patients on Lenvatinib (95% CI: 0.50–0.98; p = 0.0446), compared with patients on Sorafenib.

Patients treated with Lenvatinib showed a higher percentage of response rate (37.6 vs. 9.7; p < 0.00001) and disease control rate (73.1 vs. 49.5; p = 0.002) compared to patients treated with Sorafenib.

Table 2 reports the AEs observed. Overall, 96.4% and 94.6% experienced at least one (any grade) AE in Lenvatinib and Sorafenib arm, respectively. Main drug-related AEs in Lenvatinib arm were fatigue (57.0%), decrease appetite (55.9%) and hypertension (54.8%). Conversely, Main drug-related AEs in Sorafenib arm were HFSR (48.3%) decrease appetite (47.3%), fatigue (35.5%), and hypertension (33.4%). Data highlighted that Sorafenib was correlate with more HFSR (p = 0.000001), while Lenvatinib was correlate with more hypertension (p = 0.003) and fatigue (p = 0.005).

| Lenvatinib arm | Sorafenib arm | ‘P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| All toxicity | |||

| No | 3.6 | 5.4 | |

| Yes | 96.4 | 94.6 | 0.72 |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 48.4 | 44.2 | |

| >2 | 51.6 | 50.4 | 1.00 |

| HFSR | |||

| No | 76.4 | 51.7 | |

| Yes | 23.6 | 48.3 | <0.000001 |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 19.3 | 21.5 | |

| >2 | 4.3 | 26.8 | 0.004 |

| Diarrhea | |||

| No | 91.4 | 89.2 | |

| Yes | 8.6 | 10.8 | 0.80 |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 4.3 | 3.2 | |

| >2 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 0.63 |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 45.2 | 66.6 | |

| Yes | 54.8 | 33.4 | 0.003 |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 43.0 | 18.3 | |

| >2 | 11.8 | 15.1 | 0.029 |

| Fatigue | |||

| No | 43.0 | 64.5 | |

| Yes | 57.0 | 35.5 | 0.005 |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 39.8 | 22.6 | |

| >2 | 17.2 | 12.9 | 0.63 |

| Decrease appetite | |||

| No | 44.1 | 52.7 | |

| Yes | 55.9 | 47.3 | 0.30 |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 38.7 | 38.7 | |

| >2 | 17.2 | 8.6 | 0.79 |

| Proteinuria | |||

| No | 65.6 | NR | |

| Yes | 34.4 | NR | |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 20.4 | NR | |

| >2 | 14.0 | NR | |

| Hypothyroidism | |||

| No | 54.8 | NR | |

| Yes | 45.2 | NR | |

| GRADE | GRADE | NR | |

| 1–2 | 45.2 | NR | |

| >2 | 0 | ||

| Other toxicity | |||

| No | 18.3 | 16.1 | |

| Yes | 81.7 | 83.9 | |

| GRADE | |||

| 1–2 | 75.3 | 73.1 | 0.70 |

| >2 | 6.4 | 10.8 | 0.42 |

- Note: Numbers written in bold correspond to the statistically significance p.

- Abbreviations: AFP, Alpha-fetus protein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; HR, Hazard Ratio; HFSR, Hand-Foot Skin Reaction; NLR, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio; NV, Normal Value; OS, Overall Survival.

In patients with response rate (Lenvatinib arm 29.8 vs. 24.2 months in Sorafenib arm; p = 0.57) and post-progression anticancer medication (Lenvatinib arm 22.8 vs. 17.8 months in Sorafenib arm; p = 0.33) no different were found in term of OS between two arms.

OS with respect to patient baseline characteristics of both cohorts are also shown in Table 3. Data highlighted the prognostic role of BCLC stage, Performance status, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase as continue variable and eosinophils for the arm of patients treated with Sorafenib. Conversely, data highlighted the prognostic role of albumin, AST and alkaline phosphatase as continue variables and NLR in patients treated with Lenvatinib.

| Sorafenib arm HR (IC 95%) | p value | Lenvatinib arm HR (IC 95%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <65 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >65 | 1.07 (0.68–1.68) | 0,7527 | 1.26 (0.65–2.43) | 0,5079 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.24 (0.60–2.55) | 0,5200 | 1.02 (0.49–2.12) | 0,9512 |

| BCLC stage | ||||

| B | 1 | 1 | ||

| C | 1.67 (1.07–2.60) | 0,0257 | 1.24 (0.69–2.22) | 0,4697 |

| Etiology | ||||

| HCV | 1 | 1 | ||

| HBV | 0.99 (0.53–1.85) | 0.62 (0.29–1.33) | ||

| Others | 1.10 (0.67–1.79) | 0,9179 | 0.52 (0.27–0.99) | 0,1197 |

| Performance status | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.83 (1.03–3.23) | 0,0132 | 0.70 (0.36–1.35) | 0,3409 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.37 (0.72–2.65) | 0,2749 | 0.56 (0.26–1.20) | 0,2237 |

| Albumin | ||||

| >NV | 1 | 1 | ||

| <NV | 0.83 (0.53–1.32) | 0,4596 | 2.02 (1.01–4.02) | 0,0182 |

| Bilirubin (C.V.) | 1.54 (1.05–2.25) | 0,0250 | 2.03 (1.15–3.58) | 0,0145 |

| ALBI grade | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 1.73 (0.47–6.33) | 0.2899 | 1.30 (0.67–2.50) | 0.3788 |

| ALT (C.V.) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0,6629 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0,5745 |

| AST (C.V.) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0,4432 | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0,0035 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (C.V.) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0,0012 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0,0351 |

| AFP | ||||

| <400 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >400 | 1.27 (0.75–2.15) | 0,3269 | 1.80 (0.88–3.65) | 0,0559 |

| NLR | ||||

| <3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >3 | 1.20 (0.77–1.88) | 0,3993 | 2.75 (1.52–4.98) | 0,0004 |

| Eosinophils | ||||

| >50 | 1 | 1 | ||

| <50 | 2.16 (1.23–4.81) | 0,0090 | 1.09 (0.56–2.14) | 0,7830 |

| Extrahepatic spread | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.60–1.46) | 0,7844 | 1.34 (0.75–2.38) | 0,3124 |

| Creatinine (C.V.) | 0.85 (0.39–1.84) | 0,6797 | 1.60 (0.59–4.32) | 0,3542 |

- Note: Numbers written in bold correspond to the statistically significance p.

- Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetus protein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HR, Hazard Ratio; NLR, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio; NV, Normal Value; OS, Overall Survival.

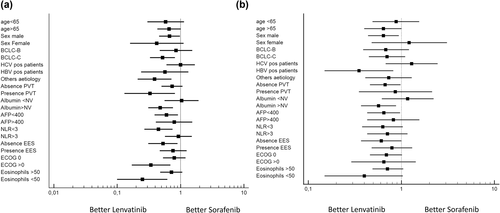

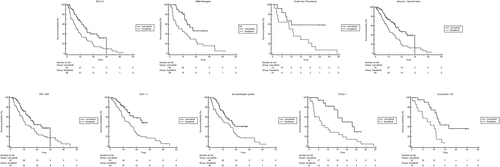

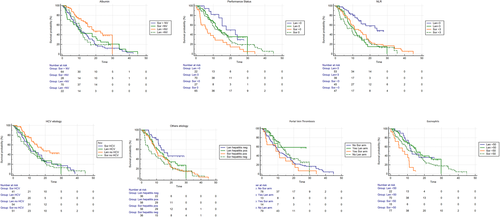

Forest plot (Figure 2a) highlighted that Lenvatinib had better overall survival respect Sorafenib in patients with BCLC-C stage (Figure 3a), others etiology (Figure 3b), presence of portal vein thrombosis (Figure 3c), albumin > NV (Figure 3d), AFP < 400 (Figure 3e), NLR < 3 (Figure 3f), absence of extrahepatic spread (Figure 3g), ECOG 1 (Figure 3h) and eosinophil < 50 (Figure 3i) (Table 4).

Forest plots for overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b)

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS in Sorafenib and Lenvatinib cohorts respect to BCLC-C stage (a), others etiology (b), presence of portal vein thrombosis (c), albumin > NV (d), AFP < 400 (e), NLR < 3 (f), absence of extrahepatic spread (g), ECOG 1 (h) and eosinophil < 50 (i). Abbreviations: BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; NLR, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio; OS, Overall Survival; NV, Normal Value; PFS, Progression-Free Survival

| Median OS | HR (CI 95%) | p value | Interaction test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib arm | Lenvatinib arm | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <65 | 10.1 (6.7–17.8) | 22.8 (7.5–29.8) | 0.58 (0.30–1.14) | 0.1186 | |

| >65 | 10.8 (6.8–44.9) | 14.9 (11.2–18.6) | 0.66 (0.43–1.01) | 0.0580 | 0,7588 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 10.5 (7.9–44.9) | 14.9 (11.4–29.8) | 0.67 (0.46–0.98) | 0.0505 | |

| Female | 10.8 (2.7–22.8) | 15.2 (7.0–15.2) | 0.42 (0.16–1.12) | 0.0857 | 0,4773 |

| BCLC stage | |||||

| B | 15.8 (10.0–44.9) | 16.8 (11.4–18.6) | 0.85 (0.47–1.54) | 0.6111 | |

| C | 7.9 (4.9–10.9) | 14.9 (10.0–29.8) | 0.52 (0.33–0.82) | 0.0049 | 0,3380 |

| Etiology | |||||

| HCV | 10.8 (8.3–38.5) | 12.4 (8.3–29.8) | 1.00 (0.60–1.68) | 0.9794 | 0,0512 |

| HBV | 10.9 (7.9–44.9) | 18.6 (7.0–22.8) | 0.57 (0.24–1.33) | 0.1959 | 0,9013 |

| Others | 9.3 (4.1–14.6) | 17.5 (11.4–17.5) | 0.39 (0.21–0.72) | 0.0029 | 0,0691 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | |||||

| No | 10.5 (7.9–44.9) | 14.9 (11.4–29.8) | 0.74 (0.50–1.08) | 0.1327 | |

| Yes | 8.7 (2.3–34.2) | NR | 0.33 (0.13–0.82) | 0.0279 | 0,0959 |

| Albumin | |||||

| <NV | 9.5 (4.7–44.9) | 11.2 (7.0–13.2) | 1.04 (0.56–1.93) | 0.8788 | |

| >NV | 10.8 (7.9–14.9) | 18.6 (14.9–29.8) | 0.48 (0.31–0.76) | 0.0016 | 0,0357 |

| AFP | |||||

| <400 | 10.5 (7.0–44.9) | 17.5 (12.7–29.8) | 0.60 (0.39–0.91) | 0.0210 | |

| >400 | 10.1 (4.3–34.2) | 12.4 (5.4–18.6) | 0.80 (0.41–1.54) | 0.5173 | 0,5386 |

| NLR | |||||

| <3 | 13.4 (8.7–44.9) | 24.0 (14.9–24.0) | 0.45 (0.27–0.75) | 0.0041 | |

| >3 | 9.5 (5.2–35.7) | 11.2 (7.0–29.8) | 0.93 (0.57–1.51) | 0.7723 | 0,0562 |

| Extrahepatic spread | |||||

| No | 10.9 (5.6–17.8) | 16.8 (11.2–18.6) | 0.53 (0.31–0.90) | 0.0205 | |

| Yes | 10.5 (8.0–44.9) | 14.9 (11.2–29.8) | 0.76 (0.47–1.25) | 0.2997 | 0,3888 |

| Performance status | |||||

| 0 | 12.7 (9.5–44.9) | 14.0 (11.2–29.8) | 0.80 (0.53–1.20) | 0.2889 | |

| 1 | 6.4 (2.7–34.2) | 15.5 (13.2–24.0) | 0.34 (0.17–0.69) | 0.0047 | 0,0283 |

| Eosinophils | |||||

| >50 | 12.7 (8.7–44.9) | 15.2 (12.4–29.8) | 0.72 (0.48–1.07) | 0.1187 | |

| <50 | 8.3 (2.1–11.0) | 12.0 (8.7–16.8) | 0.25 (0.10–0.62) | 0.0030 | 0,0524 |

- Note: Numbers written in bold correspond to the statistically significance p.

- Abbreviations: AFP, Alpha-fetus protein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HR, Hazard Ratio; NLR, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio; NV, Normal Value; OS, Overall Survival.

Forest plot (Figure 2a) highlighted that Lenvatinib had better progression-free survival respect Sorafenib in patients with AFP < 400, absence of extra hepatic spread, gender male, absence of portal vein thrombosis and normal value of albumin (Figure 2b).

Interaction test highlighted the positive predictive role of albumin > NV, ECOG > 0, NLR < 3, patients without Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) positivity, patients hepatitis negative and presence of portal vein thrombosis in favor of Lenvatinib arm; Conversely, eosinophil < 50 and ECOG > 0 were negative predictive for Sorafenib arm (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS in Sorafenib and Lenvatinib cohorts respect to albumin > NV (a), ECOG > 0 (b), NLR < 3 (c), patients without HCV positivity (d), patients hepatitis negative (e), presence of portal vein thrombosis (f), and eosinophil < 50 (g). Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; NLR, Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio; NV, Normal Value

DISCUSSION

This analysis based on real-word data demonstrated significant advantage in terms of OS of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib. For improve the quality of the result of this study and for reduce the bias of this retrospective study we used a propensity score for balance the effect of uncontrollable factors that can impact the results of an experiment. Moreover, the Response Rate (RR) and the Disease Control Rate (DCR) resulted in the two study cohorts confirmed the superiority of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib (p < 0.00001 and p = 0.002, respectively).

Another important aspect was that both the median OS and RR obtained in the Lenvatinib arm of our study resulted to be longer than the ones of the Lenvatinib group in the REFLECT trial (15.2 vs. 13.6 months; 37.6% vs. 29.6%, respectively).12 This occurred even though the present study population included patients with >50% of hepatic involvement and with main portal vein invasion, which constitutes a subset of patients excluded in the REFLECT trial. On the other hand, the present study population included patients with less BCLC-C stage (36% vs. 78%), ECOG 1 (19% vs. 36%), Extra Hepatic Disease (EHD; 29% vs. 61%) diseases. Even though a direct comparison between the two survival values is inappropriate for the overmentioned reasons, this study demonstrated that patients treated with Lenvatinib in real life can reach a very high mOS, similar to thus obtained in a phase III trial. In a previous work conducted by our research on 385 patients receiving Lenvatinib and 555 patients receiving Sorafenib, Lenvatinib did not show a survival benefit over Sorafenib (HR: 0.85, 95% CI 0.70–1.02), even after an inverse probability of treatment weight adjustment (HR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.62–1.07).17 On the other hand, the survival curves we reported in the previous work showed an overlap since start until about 1 year of follow-up, thus suggesting the presence of a “harvesting effect,” meaning that it is likely that Lenvatinib could provide a benefit with respect to Sorafenib in those patients with less advanced tumor spread, and whose baseline conditions are not so compromised. What we concluded in this previous work, was that Lenvatinib was likely to be superior to Sorafenib, but with a magnitude of effect which is not immediately detectable.17 It is probably that the differences in terms of results reported in the present work and our previous work could be related to two different samples of patients, which show different magnitudes and different baseline characteristics, and to the choice of statistical methodology. Nevertheless, we can recognize that both the works are consistent in showing a trend toward a better survival outcome obtained by treating patients with Lenvatinib in first-line therapy. Nowadays, the optimal choice between Sorafenib and Lenvatinib as primary treatment in clinical practice is still controversial. Moreover, the recent approval of the combination atezolizumab plus bevacizumab make further complex the choice of the best treatment in this clinical setting. The IMbrave150 trial demonstrated a benefit in terms of OS and PFS of the new combination compared to Sorafenib, by showing an OS at 12 months and a PFS of 67.2% (95% CI 61.3–73.1) and 6.8 months (95% CI 5.7–8.3) with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and 54% (95% CI 45.2–64.0) and 4.3 months (95% CI 4.0–5.6) with Sorafenib, respectively.14

Nowadays, no prospective trials have been conducted to direct compare the combination strategy (atezolizumab plus bevacizumab) with Lenvatinib. A network meta-analysis has been recently presented at ASCO annual meeting, with the purpose to indirectly compare multiple studies looking at atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus Lenvatinib. Data from the exploratory analysis suggested that the benefit of the combination regimen is not statistically significant for patients with advanced HCC. More specifically, researchers reported an estimated median hazard ratio (HR) for the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab compared to Lenvatinib of 0.81 (95% CrI: 0.61, 1.08; posterior P = 0.078) for overall survival (OS). When looking at PFS, the median HR was 0.99 (95% CrI: 0.76, 1.28; posterior P = 0.454) between atezolizumab and bevacizumab compared to Lenvatinib.18 Since data are already insufficient and no validated biomarkers exist in clinical practice able to select patients which are likely to respond to a regimen instead to another, treatment with the approved TKIs remain a main stone in this setting of patients, and real-word data are mandatory in order to optimize the knowledge.

The aim of our study was to fill this gap by evaluating the efficacies and safeties in a real-word setting and identifying prognostic and predictive factors of response to Lenvatinib and Sorafenib, thus helping clinicians in the decision-making process.

Basically, the liver function and stage disease are the most important prognostic parameters for both drugs.

BCLC stage has been evaluated as clinical predictive criterion of response to Sorafenib in both the SHARP trial4 and in the real-life SOFIA trial, where it was reported a significant survival advantage in BCLC-B patients treated with Sorafenib compared to BCLC-C patients (mOS 20.6 vs. 8.4 months, p < 0.0001, respectively).19 More recently, a pooled analysis of SHARP and Asia-Pacific trials confirmed the prognostic and predictive role of BCLC-B stage compared to BCLC-C in advanced HCC patients treated with Sorafenib (HR = 1.59, p = 0.02).20 This study highlighted that serum bilirubin and serum albumin values turned out to be prognostic factors for Lenvatinib and Sorafenib treatments, respectively. Moreover, albumin > NV was highlighted to be a predictive factor in favor of Lenvatinib treatment. Of note, both the bilirubin and albumin values are included in the Child-Pugh score, which is the hepatic function's parameter used in the BCLC staging system.21, 22 Similarly, as parameter of the BCLC stage, the ECOG PS was expected to result a prognostic factor.23, 24 Actually, in the present study, ECOG PS was highlighted to be not only prognostic, but predictive factor both in patients treated with Sorafenib and Lenvatinib. Considering a treatment burdened with important AEs as TKI treatment, a good ECOG PS could be related to a better treatment tolerability, thus reducing the treatment suspension and, consequently, improving the outcomes.

Other parameter that was found having a good correlation with the prognosis in Lenvatinib arm, was increased AST value, which is inconsistent with a previous analyses of SHARP and AP trials.25 Pathological process related to high proliferative status, high tumor cell turnover and tissue damage lead to an increase of AST but not ALT,26 thus probably explaining the negative prognostic impact of AST but not ALT.

The HCV related etiology was revealed to be a negative predictor of response to Lenvatinib in our analysis. This interesting result is consistent with data reported in a previous network metanalysis that demonstrated a greater efficacy of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib in HBV-positive patients.27 In the optic to find new tools to guide treatment decision, the identification of biomarkers, including ones related to the HCC's etiology,28 able to predict response or resistance to treatments is of meaningful importance.

This study highlighted other prognostic and predictive factors besides the liver function. In the last years a growing interest in the interplay between HCC, inflammatory microenvironment and circulating immune cells has emerged.29-31 The present study revealed a positive predictor role of NLR value < 3 in favor to Lenvatinib. Data highlighted that in the subgroup of patients treated with Lenvatinib it was reached a mOS of 24 months compared to only 13.4 months in patients treated with Sorafenib. No significant differences were found in patients with NLR > 3 in the two cohorts of patients. In the sub-analysis of SHARP and Asia-Pacific trials conducted by Bruix et al.,20 NLR has already demonstrated to be a discrimination tool for patients which reached benefit or not from Sorafenib. In our knowledge, this is the first study which demonstrated the predictive role of NLR in patients treated with Lenvatinib.

Another important point revealed in our analysis was the negative predict role of eosinophil count in patients treated with Sorafenib. In a previous work, Orsi et al. demonstrated a negative prognostic impact of eosinophil count <50 in a training cohort and in two validation cohorts.32 Our study demonstrates for the first time the predictive role of this peripheral cells.

A further point of discussion is the safety profile. In our analysis, the incidence of AEs of any grade in the two treatment arms is similar, but the quality of toxicity profile is different. In the Sorafenib arm the incidence of HFRS in significantly higher, while in the Lenvatinib arm the principal AEs reported were hypertension and fatigue. Generally, dermatological AEs are not related to risk of death, but they often compromise the patient's quality of life,33-35 which is in line with the sub-analysis of the REFLECT trial.11 Of interest, no differences in the incidence of diarrhea were reported in our study.

Our study has a number of limitations. The principal ones rely on its retrospective nature and on the lack of a standardized follow-up protocol in regard to clinical monitoring of HCC, which depended on each institution's clinical practice. Nevertheless, the present work captures real-word observational data which could help to clarify the efficacy and tolerability of Lenvatinib compared to Sorafenib in advanced HCC setting. Moreover, the use of a propensity score matching reduces the selection bias inherent in the nature of a retrospective trial which compare two heterogenous cohort of patients, thus helping the understanding of the real impact of Lenvatinib rather than Sorafenib. Since data from randomized designed to capture data of superiority of Lenvatinib over Sorafenib are not available, our results could be of clinical interest in helping physician in the daily clinical practice's choice.

CONCLUSION

In our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrated a superiority in terms of overall survival of Lenvatinib over Sorafenib in a real-word setting. This study confirmed higher response rate of Lenvatinib compared Sorafenib. For the first time, NLR < 3 has turned out to represent a good tool for preferring the use of Lenvatinib rather than Sorafenib in advanced HCC setting. The safety profile is consistent with what observed in the REFLECT trial, thus legitimating the use Lenvatinib as a first choice in the advanced HCC setting. Biomarkers able to identify responders to Lenvatinib rather than Sorafenib lack in clinical setting, and further trials of validation are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.