Effectiveness of a comprehensive educational programme for Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) to identify individuals in the Udupi district with bleeding disorders: A community-based survey

Funding information

This manuscript was produced as a part of the project titled “Identification, Diagnosis, Education, and Empowerment for Action (IDEEA) of the people with bleeding disorders in south India”, which was funded by Novo Nordisk Hemophilia Foundation, Zurich, Switzerland. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Abstract

Introduction

The awareness and knowledge on bleeding disorders is generally poor among the rural population. Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) serve as the facilitators between the rural community and the health care system. Training of ASHAs in screening of rural population for early identification of bleeding disorders can enable prompt referral, timely detection and management of bleeding disorders.

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an ASHA training programme for identification of suspected bleeding disorder cases.

Methods

A population-based, cross-sectional survey was implemented by 586 Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in rural Udupi district, who underwent a structured training programme on identification of bleeding disorders. A survey record book with a screening tool on assessment of bleeding symptoms was given to each ASHA. The screening tool consisted of symptoms related to bleeding disorders and family history of bleeding disorders. Using the screening tool, ASHAs carried out a door-to-door survey. After screening, those who reported with bleeding symptoms were referred by the ASHAs to the investigator, who conducted further assessment. A detailed bleeding history was documented and bleeding symptom assessment was carried out using bleeding assessment tool (BAT) at the haemophilia treatment centre. Further coagulation assessments were carried out as per the treatment centre protocol. This paper highlights the evaluation of an ASHA training programme on identification of individuals with bleeding symptoms in the rural population.

Results

A total of 586 trained ASHAs surveyed a population of 318 214 in rural Udupi district. Out of the 124 cases reported by ASHAs, 29 bleeding disorder cases were identified; haemophilia (A and B) was the most commonly found bleeding disorder 22 (75.8%), followed by von Willebrand disease (vWD) 3 (10.3%) and 4 (13.8%) immune-mediated thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), with an overall prevalence of 2.2/10 000 population.

Conclusion

Training ASHA health care workers, who are the most important link between the community and health services, resulted in increased awareness among the public for the early detection of bleeding disorders.

1 INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of bleeding disorders could be as high as 1% of the population, depending on what type of bleeding disorder is included and what are the diagnostic measures used. Haemophilia, vWD, factor deficiencies and platelet function disorders are the types of bleeding disorders seen in the population.1 The 2015 WFH Global Annual Survey reported that individuals with a bleeding disorder received the following diagnoses: 187 183 with haemophilia, 74 819 with von Willebrand disease (vWD) and 42 360 with other bleeding disorders (rarer factor deficiencies and inherited platelet disorders) and in India 18 134 patients had a bleeding disorder, of which 17 346 had haemophilia and 788 had some other bleeding disorder.2 An active surveillance system used to identify all residents of Colorado, Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York and Oklahoma with haemophilia reported that the age-adjusted prevalence of haemophilia in all six states in 1994 was 13.4 cases/100 000 males (10.5 for hemophilia A and 2.9 for B).3 However, the current case detection in India is much lower than the USA, which has an excellent Haemophilia surveillance system in comparison.4 WFH data suggest that only 20% of people with a bleeding disorder in India are diagnosed.5 Thus, underdiagnoses of bleeding disorders in developing countries such as India are evident.

Educating health care professionals about bleeding disorders in the community is one approach to address this need. Without a diagnosis, people cannot receive the treatment they need. On the other hand, without an accurate number of people known to be affected by the disorder, governments are much less likely to provide funding for the treatment and research required for better treatment. Haemophilia A is the most commonly inherited bleeding condition, constituting 80% of reported cases.6 Bleeding disorders often are inherited conditions that last throughout a person's life, and although treatment is available for bleeding disorders, a cure is not always possible. Often, affected individuals or family members do not recognize the disorder or ignore the bleeding disorder completely. This article reports the results of a survey carried out by trained Accredited Social Health Activists (AHSAs) to screen individuals with bleeding symptoms and their subsequent referral for confirmation of bleeding disorders. This study is part of a project titled Identification Diagnosis Education and Empowerment for Action (IDEEA) of persons with bleeding disorders in South India.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study population and setting

The study was carried out in three taluks of the Udupi district viz.: Kundapur, Udupi and Karkala. This area consists of 233 villages with 177 762 households, including a rural population of 843 300, which represents 72% of the total population as per the 2011 census.7 As part of the health care system, ASHAs assist in the delivery of care in underserved populations living in the rural areas of the district. Each ASHA is meant to cover a population of 1000 and receives performance- and service-based compensation for home visit and referrals for appropriate medical care.8-10 Prior to implementing the study, permission from the Director of Health and Family Welfare Karnataka was obtained to utilize the ASHA services. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Kasturba Hospital, Manipal.

2.2 ASHA training programme

The training programme for identifying individuals with bleeding disorders was conducted at the Udupi district level with the help of a training manual on identification of cases with bleeding disorders.11 The content of the training manual consisted of six sections: basic elements of blood; the blood clotting process; bleeding disorders and their types; screening people with bleeding symptoms; managing bleeding disorders; and the role and responsibility of community health workers. ASHAs were provided with a skill-based training programme in the local language (Kannada) for 1 day at the community health centre using a training manual geared towards identifying people with bleeding disorders. The training also included a session concerning home visits, with a guide on how to perform an assessment at the community level to screen for bleeding symptoms. A total of 586 ASHAs were trained by the investigator with support from ASHA mentors and a social worker. A hands-on training programme was carried out through role-playing of a home visit to assess for bleeding symptoms in the family using the screening tool.

2.3 Development, pretesting and piloting of Screening Questionnaire

A questionnaire was designed and developed to screen the rural community for possible bleeding symptoms in order to identify suspected bleeding disorder cases. The questions were framed after thorough literature review and its content was validated by giving to experts from the fields of nursing, public health, community health and clinical haematology. The content validity of the screening questionnaire was established in terms of accuracy, relevancy and appropriateness of the question in the tool by subject experts. There was 100% agreement among all the experts and scale content validity index (SCVI) of tools was 1. The validated tool consisted of two sections. The first part included socio-demographic information including the name of the head of family and informant, home address, number of members in the family, gender and phone number. The second section (Table 1) of the tool included questions on bleeding symptoms, which were related to the areas of focus such as family history of bleeding disorders and presence of bleeding symptoms.

|

1. Do you or any of your family members have any bleeding disorder, such as hemophilia or von Willebrand disease? Or have you ever needed medical attention for a bleeding problem? 2. Have/do you or any of your family members had/have prolonged bleeding problems: • after surgery • from the gums, after brushing, loss of teeth, with dental procedures • with a mild trauma or injury • during menstruation or child birth • easy bruisability with swelling under the skin • joint swelling due to spontaneous bleeding into the joints |

After content validation of the screening questionnaire, it was then translated into the local language (Kannada) and pretested by five ASHAs on a group of five people with no bleeding disorders and a group of five people with bleeding disorders in a hospital setup. After pretesting, the questions in the questionnaire were reframed and improved to enable efficient screening of bleeding symptoms by the ASHAs. A pilot test was performed on 10 ASHAs to assess their skill in administering the questionnaire and evaluating the signs and symptoms of bleeding disorders. During the pilot testing, ASHAs visited households in the community, under the observation of an investigator who monitored the quality of the assessment performed by the ASHAs. Each ASHA was given a log book that contained the purpose of the screening, instructions for door-to-door surveying and screening questions.

2.4 Screening, referral and confirmation

A door-to-door survey was carried out by the ASHAs in the rural population using the screening questionnaire during their routine home visits, and family members were screened. The houses that were locked were revisited by the ASHAs after 1 week to complete the survey. When the ASHA workers identified cases with bleeding symptoms during the screening process, those individuals were referred to the haemophilia treatment centre where the investigator collected these individual's demographic and clinical information using demographic and clinical proforma which comprises of variables such as consanguinity, age at onset of bleeding symptom with details of bleeding, drug history, past medical and surgical history, history of blood transfusion and any blood investigation. Further assessment using a standardized bleeding assessment tool (ISTH-BAT) was done. Permission to use the BAT was obtained from the author. The BAT consisted of 14 bleeding symptoms (R), and each symptom was scored from 0, or no bleeding symptoms, to 4, the maximum number of bleeding symptoms present. The score could range from 0 to 56 in women and from 0 to 48 in men.12, 13 The BAT was tested for reliability through the inter-rater reliability method and was administered by two haemophilia nurses at the centre who rated 20 individuals presenting with bleeding symptoms at different intervals. The BAT reliability “r” value was 1, which showed that the tool was reliable. The total time taken to administer the BAT was 10-15 minutes for each individual. In the case of females who had attained menarche, additional information on blood loss at menstruation was assessed by the Pictorial Bleeding Assessment Chart (PBAC).

If the clinical data and BAT assessment indicated any bleeding diathesis wherein bleeding score (BS) is above 2, informed consent was obtained before subjecting to further screening tests such as bleeding time (BT), prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), thrombin time (TT), platelet count, factor XIII screen, clot retraction and direct smear. Depending on the result of these tests, in consultation with haematologist-specific tests (mixing studies, factor assays, von Willebrand factor (vWF) assay and platelet aggregation studies) were performed.

3 RESULTS

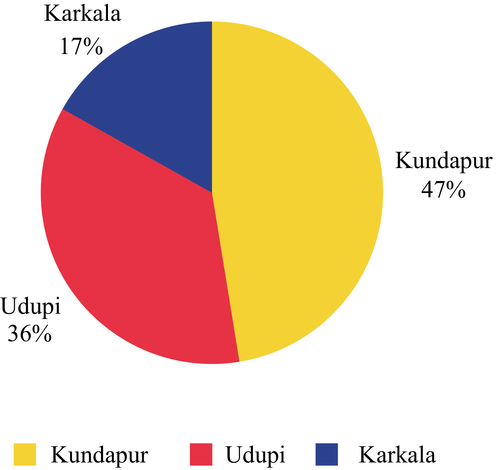

A total of 586 trained ASHAs covered a population of 318 214 in rural Udupi district. The population covered in Kundapur, Udupi and Karkala taluks was 150 937(47%), 113 620 (36%) and 53 657 (17%), respectively (Figure 1). Out of 586 ASHAs, 109 ASHAs identified and reported 124 cases of bleeding symptoms from 76 villages covering a population of 128 915 (Table 2). During the preliminary screening of 124 reported cases, 30 cases (32.2%) were excluded [17 (21.08%) had no bleeding symptoms, and 13 (10.4%) had been diagnosed with other haematological disorders] and the remaining 94 (74.8%) cases with bleeding symptoms were evaluated by the investigator using the BAT.

| Taluks of Udupi district | Number of villages covered | Number of households surveyed | Population covered | Number of cases reported with bleeding symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kundapur | 28 | 11 318 | 60 946 | 42 |

| Udupi | 34 | 9761 | 47 612 | 60 |

| Karkala | 14 | 4546 | 20 652 | 22 |

| Total | 76 | 25 625 | 128 915 | 124 |

Among the 94 cases, 54 (57%) were female. Of these, 8 (8.5%) were less than or equal to 13 years old, 36 (38%) were 14-40 years old and 9 (9.6%) were 41 years old or above. There were also 40 (43%) males. Of these, 13 (13.8%) were less than 13 years old, 17 (18%) were 14-40 years old and 10 (10.6%) were 41 years old or above (Table 3).

| <13 years | 13-40 years | >40 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 8 (8.5%) | 36 (38%) | 9 (9.6%) | 54 (57%) |

| Male | 13 (13.8%) | 17 (18%) | 10 (10.6%) | 40 (43%) |

| Total | 21 | 53 | 19 | 94 |

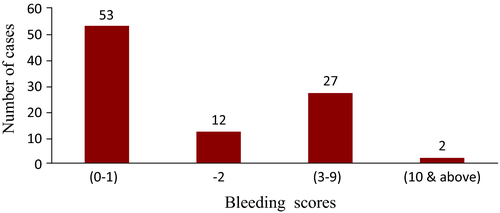

Among these 94 cases, 53 (56.4%) had a BS of 0 or 1 and were not considered for further testing because their bleeding symptoms were considered insignificant. The remaining 41(43.6%) cases had a BS of 2 or above and were considered for further workup (Figure 2). Among the 41 suspected cases, 12 (29%) cases had a BS of 2 with a normal haemostatic workup, 27 (65.9%) cases had a BS of 3-9, among whom 22 (53.7%) had prolonged APTT, 2 (4.9%) had thrombocytopenia and 3 (7.3%) had a normal screening test and were diagnosed with vWD. Two (4.9%) cases had a BS of 10 or above and had thrombocytopenia (Table 4).

| Diagnosed cases of bleeding disorders | Predominant Symptoms | BT Mean ± SD | PT Mean ± SD | APTT Mean ± SD | PLT Mean ± SD | Factor assay Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemophilia A&B (N = 22) |

Heamarthroses Bleeding after injury |

3.0 ± 0.6 | 13.3 ± 2.3 | 79.5 ± 16.7 | 266 ± 101.5 |

3.2 ± 2.7 (FVIII & IX) |

| von Willebrand type 1 (N = 3) | Menorrhagia | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 13.0 ± 13.0 | 25.7 ± 13.0 | 261 ± 66.6 |

26.8 ± 14.6 vWF Assay |

| ITP (N = 4) | Cutaneous bleed | 8.8 ± 2.4 | 16.4 ± 1.0 | 29.5 ± 3.2 | 16.1 ± 12.3 | - |

| Normal (N = 12) | Cutaneous bleed | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 15.9 ± 0.9 | 32.4 ± 4.1 | 294 ± 47.5 |

111 ± 25.9 (FVIII & IX) |

- Bleeding Time (BT): 2-8 min, Prothrombin Time (PT): 9-14 s, Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT): 24-34 s, Immune-mediated thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), FV III&IX assay): 50%-150%, vWF Ag assay: 47%-197%.

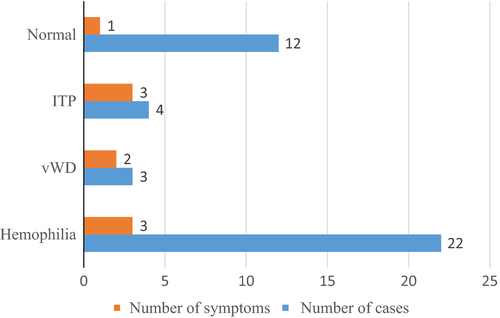

Bleeding symptom analysis revealed a number of symptoms reported by haemophilia cases. Among the 22 diagnosed cases of haemophilia A & B, the predominant symptoms seen were prolonged bleeding after injury, cutaneous bleed and joint bleed. In the 3 vWD cases which were all type I had menorrhagia as a predominant symptom. Among the four diagnosed thrombocytopenia cases, cutaneous bleed followed by prolonged bleeding after injury were the predominant symptoms (Table 4), (Figure 3).

4 DISCUSSION

This study provides an import ant insight into the utilization of ASHAs at the grass root level because efforts towards screening and identifying bleeding symptoms in the rural community have been very insignificant in low- and middle-income countries. In the present study, the ASHAs covered 42% of the population in the rural Udupi district. Black et al.14 of India reported that ASHA workers covered 60% of the villages and 54% of the rural population. Due to this deficiency there can be underreporting of cases with bleeding symptoms from the rural population by ASHAs. The results of the present study showed that out of 53 cases with bleeding symptoms as reported by ASHAs, 41 (77%) cases had significant BS and were considered for further haemostatic workup. Hence, it is important to note that such reported cases by ASHAs should be further assessed using scientific tools such as bleeding assessment tool (BAT), pictorial bleeding assessment chart (PBAC) and laboratory testing by clinicians.

The Bleeding symptom (BS) data reported by Elbatany et al.13 suggest that the cut-off for BS in children is lower than that in adults. Moreover, root cause analysis for high BS in children suggested that this condition is due to delayed referrals, inadequate differential diagnosis and symptomatic treatment. This study proves that such delayed referral can be prevented through training of ASHAs in screening and identification of bleeding disorders and thus prompting early detection, accurate diagnosis and timely treatment.

A study conducted to detect bleeding disorders in Lebanon in 2014 reported that 1.4% of the study population was diagnosed with a bleeding disorder and concluded that the prevalence of the full spectrum of various blood disorders from mild to severe may be higher than the previously assumed rate of 1%.15 These findings support the current study findings of a bleeding disorder prevalence of 2.2 per 10 000 individuals as reported by ASHAs in rural population. A hospital-based study in western India by Manisha et al.16 reported that haemophilia A (70.5%) was the most common disorder followed by haemophilia B (14%) and vWD (10.8%). These findings support those of the present study, which found that haemophilia A and B were the most commonly found bleeding disorders (75.8%), followed by vWD (10.3%) whereas one must reflect of having a possibility that vWD could be undetected because of milder bleeding symptoms. So, a much more rigorous survey of the community is needed for such an evaluation.

Accredited Social Health Activists can communicate effectively with the family members concerning health care services. They act as an important link between the community and health care system. Das VNR et al.17 in 2014 reported that there were increased referral rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis from a baseline of 7%-28% by ASHAs after a single round of training in Bihar. Similarly, the results of this study showed that the training of ASHAs on screening and identification of bleeding symptoms facilitated referral of 124 cases to the haemophilia treatment centre from the rural community as compared to zero cases of referral by ASHAs before training.

The high competency and efficiency of trained ASHAs have facilitated health care changes. However, detailed performance monitoring is limited to aggregate statistics, and detailed performance records for all ASHAs were not available. One such limitation is the inability to record the home visits of ASHAs, so it remains unclear whether they adequately cover their locations and the quality of their work is not assured, especially in remote and poorly populated areas. So, repeated training along with complete performance monitoring of ASHAs is recommended for further studies.

Training of ASHAs on screening and identification of bleeding symptoms can benefit the community through referral of suspected cases of bleeding disorders (especially children) to a facility for testing and diagnosis.18, 19 A comprehensive evaluation should occur after referral by the ASHAs from the community because bleeding symptoms are not only the major criteria to confirm bleeding disorders.20 When the referred cases had a significant bleeding history, the ISTH/BAT was practical in doing further assessment for diagnosis and confirmation of bleeding disorders. The BAT can be easily integrated into a routine clinical practice to facilitate an accurate assessment of bleeding symptoms.

5 CONCLUSION

The approach described herein resulted in an improved performance of the ASHAs in screening and identifying cases with bleeding symptoms in the rural community. As a result, the district health department adopted this training for ASHAs on bleeding disorders and for novice ASHAs during their training programme. This training programme for identifying bleeding disorders can facilitate early identification of bleeding disorders through referral and improve the health of the community. ASHAs are an important asset for health care system especially in the community as they act as facilitators in the health care delivery system and are widely accepted by the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the large network of ASHAs of the Udupi district who were part of the training programme and performed the study. We express our gratitude to Ms. Rita Rosy Rego, Ms. Anitha, Ms. Saritha, Ms. Sweatha and the ASHA Mentors for their support during the implementation of the educational programme. We express our appreciation to Mr. Gururaj Kotwal, social worker, for his efforts in coordinating the training programme at the district community health centre. We thank all members of the “Hemophilia Society”, Manipal, for their support. We express our appreciation to the local health department, Udupi district, which permitted us to perform the training programme for the current research project.

DISCLOSURES

The authors state that they have no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias. This paper was produced as a part of the Project titled “Identification, Diagnosis, Education, and Empowerment for Action” of the people with bleeding disorders in South India (IDEEA) funded by Novo Nordisk Hemophilia Foundation, Zurich, Switzerland. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

S. Badagabettu, D. M. Nayak, A. Kurien, V. Kamath and A. George contributed to the study conception and design, collection and assessment of data, data analysis and interpretation and manuscript writing/revisions. A. Kamath contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and manuscript/revisions. All authors provided final approval of the submitted manuscript.