Genetic diversity and structure of diploid Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) cultivars and breeding materials in Japan based on genome-wide allele frequency

Abstract

To reveal the genetic diversity and structure of cultivars and breeding materials of diploid Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) in Japan, using genome-wide allele frequency data obtained by genotyping by random amplicon sequencing, direct of pooled DNA, we investigated genetic diversity among and within 89 accessions. We selected 2629 reliable alleles at 456 polymorphic loci to evaluate allele frequency in each accession. Results of hierarchical cluster analysis based on Nei's standard genetic distance and of principal component analysis and nonhierarchical cluster analysis based on the complete set of allele frequencies classified the accessions into a large group including major Japanese cultivars and their ancestral landraces with a wide range of maturity, and a small group with mainly medium maturity, including ‘Gulf’, introduced from overseas. The genetic relationships fully reflected the kinship inferred from the breeding history in Japan. Mean expected heterozygosity (HE) and number of alleles per locus (A) were evaluated as indices of genetic diversity within each accession. We found a significant negative correlation between the year of application for varietal registration and HE or A in 14 early-maturing Japanese cultivars. The genetic diversity profile can be used for breeding to maintain or increase the diversity within cultivars or breeding materials.

1 INTRODUCTION

Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) is an annual ryegrass species with superior yield potential and high forage quality (Humphreys et al., 2010). In Japan, it is a typical winter forage crop, mainly in temperate and warm climates south of the Tohoku region. Its introduction into Japan can be traced back to the end of the 19th century (Nishimura, 1977). Cultivars bred overseas are still being used in Japan. Breeding in Japan was started in the public sector in the 1960s (Kinoshita et al., 1973; Yoshioka et al., 1971), followed by private seed companies. Italian ryegrass is available in diploid and tetraploid varieties, but the diploid ones are more common in Japan. Early breeding of diploid Italian ryegrass focused on early maturity, high yield and erect plants with lodging tolerance. Since then, cultivars with extremely early to medium maturities have been bred to suit regional cropping systems. In recent years, disease resistance and forage quality have also been targeted (Arakawa, 2021; Harada et al., 2003).

Owing to Italian ryegrass's allogamous and self-incompatible nature, cultivars and breeding lines consist of heterogeneous populations made up of heterozygous individuals. Generally, breeding of Italian ryegrass is based on a recurrent selection strategy, whereby a population is evaluated, a subset of superior genotypes is selected and the selected plants are intercrossed to generate a population for the next selection cycle or as a new cultivar (Humphreys et al., 2010). During recurrent selection, breeders select plants to accumulate additive gene effects, but to avoid inbreeding and reduction of genetic flexibility, it is vital to keep genetic diversity at a certain level within a population (Humphreys et al., 2010). Studies of some forage grass species suggested that selection of parents for high genetic diversity of molecular markers allows breeders to exploit heterosis, improving yield performance (Kölliker et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2011). High genetic diversity also provides insurance against environmental stresses (Prieto et al., 2015), conferring adaptability to diverse environments, which is required to secure minimum sales volumes.

Many studies have assessed genetic diversity in forage grass species using DNA-based methods (reviewed in Loera-Sánchez et al., 2019). In Italian ryegrass, random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers were used to assess genetic diversity between and within populations of breeding cultivars and ecotypes (Guan et al., 2017; Nie et al., 2019; Vieira et al., 2004). In these studies, genotyping was conducted for each individual or bulk composed of a dozen individuals within each population, but in the latter case, allele frequency cannot be evaluated. Genomic loci genotyped were limited to about 30 in these studies (Guan et al., 2017; Nie et al., 2019). In contrast, high-throughput genotyping methods such as diversity array technology (DArT) and multiplexed single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) methods (Kopecký et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014) allow hundreds to thousands of markers to be genotyped at once. The SNP method requires sequence or polymorphic information in advance. The DArT method does not, but suffers from redundancy and ascertainment bias (Loera-Sánchez et al., 2019). To overcome these limitations, Byrne et al. (2013) proposed genome-wide allele frequency fingerprints (GWAFFs) as population-based genomic profiles. GWAFFs are based on allele frequencies of thousands to tens of thousands of genome-wide SNPs obtained by genotyping-by-sequencing of the pooled DNA of a hundred individuals from each population. In addition to genetic diversity studies (Pembleton et al., 2016; Verwimp et al., 2018), GWAFFs were used to genotype heterologous populations of forage grass species as a unit in a variety of applications such as genomic prediction (Fè et al., 2016). Recently, a new random PCR-based genotyping-by-sequencing technology called genotyping by random amplicon sequencing, direct (GRAS-Di), was developed (Enoki, 2019; Enoki & Takeuchi, 2018). This method has the advantages of simplicity of library construction and useful numbers of highly reproducible polymorphisms (SNPs or indels or haplotypes) in short amplicons.

Here, to reveal the genetic diversity of cultivars and breeding materials of diploid Italian ryegrass in Japan, we investigated genetic diversity among and within 89 accessions by using genome-wide allele frequencies obtained by GRAS-Di. We discuss the genetic diversity profile in the context of the history of Italian ryegrass breeding in Japan and its application to future breeding.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

We used 89 Italian ryegrass accessions: 38 Japanese cultivars, including some bred overseas and sold in Japan, such as ‘Gulf’; 29 Japanese public breeding lines, including the inbred line ‘ILW1’ used as a check for heterozygosity; 7 traditional Japanese landraces adapted to local regions (developed by farmers); 3 Japanese ecotypes (locally adapted populations developed by natural selection); and 11 cultivars and 1 ecotype from other countries (Table 1). Table 1 also shows the origins of cultivars and breeding lines in Japan for which information is publicly available as far as we know. It also shows year of application for Japanese Plant Variety Protection (PVP, http://www.hinshu2.maff.go.jp/en/en_top.html) or its forerunner (before 1978) for cultivars. When the original seeds of cultivars were available, we sowed those; when they were not available, we sowed commercial seeds.

| Acc. No. | Acc. name | Source | Accession type | Heading datea | Maturity typeb | Year of application for Japanese PVP | Originc and characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Waseaoba | CARC/NARO, Japan | Cultivar | 52.6 | Early | 1970 | From ‘Tottori Zairai’ (68) |

| 2 | Nioudachi | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Cultivar | 54.6 | Early | 1995 | From ‘Waseaoba’ (1) |

| 3 | Nakei 33 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Cultivar | 55.1 | Early | 2016 | Back-crossed progeny of genotypes with crown rust resistance from ‘Hataaoba’ (25) |

| 4 | Nasuhikari | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Cultivar | 70.1 | Late | 1974 | From ‘Tottori Zairai’ (68) and 16 cultivars |

| 5 | Hm4Pc | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 34.7 | Extremely early | From two genotypes of progeny of a single cross ‘Sachiaoba’ (32) × ‘Waseaoba’ (1), crown rust resistance | |

| 6 | BMSL | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 48.2 | Extremely early | ||

| 7 | BMS1 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | – | Early | ||

| 8 | BMS2 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | – | Early | ||

| 9 | Nakei 34 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 55.4 | Early | Back-crossed progeny of genotypes with crown rust resistance from ‘Hataaoba’ (25) | |

| 10 | Nakei 38 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 52.1 | Early | From 31 breeding lines and cultivars: ‘Nioudachi’ (2), ‘Hataaoba’ (25), ‘Yushun’ (26), ‘VE02’ (47), ‘Inazuma’ (48), ‘Satsukibare’ (52), ‘Tachiwase’ (57) and ‘Tachimasari’ (58), same as ‘Nakei 35’ (15) | |

| 11 | BME2 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 50.6 | Early | From 22 breeding lines and cultivars: ‘Waseaoba’ (1), ‘Nioudachi’ (2), ‘Nasuhikari’ (4), ‘Hataaoba’ (25), ‘Yushun’ (26), ‘Yamaiku 185’ (36), ‘Yamaiku 177’ (38), ‘Yamaiku 180’ (40), ‘Yamakei 32’ (41), ‘Yamakei 34’ (42), ‘VE02’ (47), ‘Inazuma’ (48), ‘Harukaze’ (51), ‘Tachiwase’ (57), ‘Tachimasari’ (58), ‘Tachimusha’ (60), ‘Miyazaki Zairai’ (69) and ‘Magnolia’ (85) | |

| 12 | LNG9 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 52.3 | Early | From ‘Parental Line Nou 3’ (13), low nitrate-N | |

| 13 | Parental Line Nou 3 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 54.4 | Early | 2010 | From ‘Nioudachi’ (2), ‘Waseyutaka’ (34), ‘Tachimasari’ (58) and ‘Tachimusha’ (60), low nitrate-N |

| 14 | Parental Line Nou 2 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 57.9 | Medium | 2007 | From three genotypes of progeny of a single cross ‘Yamaiku 130’ (43) × ‘Waseaoba’ (1), crown rust resistance |

| 15 | Nakei 35 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 61.5 | Medium | From 31 breeding lines and cultivars: ‘Nioudachi’ (2), ‘Hataaoba’ (25), ‘Yushun’ (26), ‘VE02’ (47), ‘Inazuma’ (48), ‘Satsukibare’ (52), ‘Tachiwase’ (57) and ‘Tachimasari’ (58), same as ‘Nakei 38’ (10) | |

| 16 | ILW1 | ILGS/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 65.7 | Late | S6 inbred line from one genotype of ‘Waseaoba’ (1) | |

| 17 | Kyushu 1 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Cultivar | 34.8 | Extremely early | 2017 | From ‘Yamaiku 185’ (36) and ‘Yamakei 32’ (41), blast resistance |

| 18 | Kyushu 3 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 26.4 | Extremely early | From ‘Yamaiku 185’ (36) and ‘Yamakei 32’ (41), blast resistance | |

| 19 | Kikukei 13 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 57.4 | Medium | From ‘Hataaoba’ (25), ‘Yamaiku 185’ (36), ‘Yamaiku 167’ (37), ‘Yamakei 32’ (41), ‘Inazuma’ (48) and ‘Tomokei 30’ | |

| 20 | QGB17 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 58.5 | Medium | From 6 ecotypes collected in Kagoshima prefecture, Japan (‘08-KK-02’ [74], ‘08-KK-05’ [75] and ‘08-KK-08’ [76]), ‘Imperial’ (82) and ‘Magnolia’ (85) | |

| 21 | QM16 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 62.3 | Medium | From ‘Satsukibare’ (52), ‘Tachimusha’ (60) and ‘Tomokei 30’ | |

| 22 | QE19 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 52.0 | Early | From ‘Nakei 38’ (10), ‘Nakei 35’ (15), ‘Hataaoba’ (25), ‘08-KK-08’ (76), ‘Magnolia’ (85) and some breeding lines | |

| 23 | QM19 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 61.0 | Medium | From ‘Nakei 38’ (10), ‘Nakei 35’ (15), ‘Hataaoba’ (25), ‘SI-14’ (59), ‘KAIR-12M’ (53), ‘08-KK-02’ (74), ‘08-KK-05’ (75), ‘08-KK-08’ (76), ‘Imperial’ (82), ‘Magnolia’ (85) and some breeding lines including lines from QM16 | |

| 24 | QML19 | KARC/NARO, Japan | Breeding line | 65.9 | Late | From ‘Nakei 35’ (15), ‘08-KK-05’ (75), ‘08-KK-08’ (76), ‘Dasas’ (78), ‘Baroldi’ (79), ‘Imperial’ (82) and some breeding lines | |

| 25 | Hataaoba | IPLRC, Japan | Cultivar | 53.6 | Early | 2003 | From breeding lines in IPLRC and ‘Uzukiaoba’, ‘Tachiwase’ (57) and ‘Nioudachi’ (2) |

| 26 | Yushun | IPLRC, Japan | Cultivar | 49.3 | Early | 2005 | From ‘Nioudachi’ (2), ‘Tachiwase’ (57) and 3 breeding lines |

| 27 | Haruyutaka | IPLRC, Japan | Cultivar | 52.1 | Early | 2015 | From some cultivars, low Ob (low digestible fiber) |

| 28 | Tomoiku 160 | IPLRC, Japan | Breeding line | 52.8 | Early | ||

| 29 | Tomokei 32 | IPLRC, Japan | Breeding line | – | Early | ||

| 30 | Minamiaoba | YPAFGTC, Japan | Cultivar | 42.7 | Extremely early | 1988 | From ‘Minamiwase’ (33), ‘Waseyutaka’ (34) and ‘W:Florida R.R.’ |

| 31 | Shiwasuaoba | YPAFGTC, Japan | Cultivar | 31.6 | Extremely early | 1998 | From ‘Minamiwase’ (33) |

| 32 | Sachiaoba | YPAFGTC, Japan | Cultivar | 31.6 | Extremely early | 2002 | From ‘Yamaiku 176’ |

| 33 | Minamiwase | YPAFGTC, Japan | Cultivar | 35.1 | Extremely early | 1977 | From 4 landraces (‘Ibaraki Zairai’ [67], ‘Tottori Zairai’ [68], ‘Kuroishi Zairai’ [70], ‘Kochi Zairai’ [71]), 6 Australian cultivars and 1 US cultivar |

| 34 | Waseyutaka | YPAFGTC, Japan | Cultivar | 52.8 | Early | 1972 | From ‘Tottori Zairai’ (68), ‘Kuroishi Zairai’ (70) and ‘Kochi Zairai’ (71) |

| 35 | Yamaaoba | YPAFGTC, Japan | Cultivar | 70.1 | Late | 1972 | From 3 overseas cultivars (‘B2138’, ‘C·B’ and ‘Gorka Norodowa’) and ‘Obahikari’ |

| 36 | Yamaiku 185 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 31.6 | Extremely early | From 10 cultivars: ‘Sachiaoba’ (32) and ‘Yamakei 32’ (41), blast resistance | |

| 37 | Yamaiku 167 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 49.1 | Early | From ‘Yamakei 30’ | |

| 38 | Yamaiku 177 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 52 | Early | From ‘Yamaiku 167’ (37) | |

| 39 | Yamaiku 179 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 53.3 | Early | ||

| 40 | Yamaiku 180 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 52.3 | Early | From some cultivars: ‘Yamakei 30’ and ‘Sachiaoba’ (32), blast resistance | |

| 41 | Yamakei 32 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 55.7 | Early | From 3 breeding lines: ‘Yamakei 30’ | |

| 42 | Yamakei 34 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 52.5 | Early | From 14 breeding lines: with high digestibity and 3 overseas cultivars | |

| 43 | Yamaiku 130 | YPAFGTC, Japan | Breeding line | 58.1 | Medium | Inbred line from ‘Gulf’ (88) genotype(s) with crown rust resistance | |

| 44 | Niigatakei | NAES, Japan | Cultivar | 69.2 | Late | From commercial cultivars sold in 1954 | |

| 45 | JFIR-20 | JGAFSA, ILGS/NARO, Takii, Japan | Cultivar | 51.4 | Early | 2014 | From progeny of ‘Parental Line Nou 3’ (13) × one breeding line, low nitrate-N |

| 46 | Hayamaki 18 | JGAFSA, Japan | Cultivar | 50.1 | Early | 2015 | |

| 47 | VE02 | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 48.3 | Extremely early | 2006 | |

| 48 | Inazuma | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 51.7 | Early | 2004 | From 3 ecotype populations in Japan |

| 49 | Raizin | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 52.1 | Early | ||

| 50 | LN-IR01 | Kaneko Seeds, ILGS/NARO, Japan | Cultivar | 54.5 | Early | 2013 | From progeny of ‘Parental Line Nou 3’ (13) × one cultivar, low nitrate-N |

| 51 | Harukaze | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 56.4 | Medium | Introduced from another country | |

| 52 | Satsukibare | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 62.8 | Medium | 2006 | |

| 53 | KAIR-12M | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 60.1 | Medium | 2014 | |

| 54 | Excellent 2 | Kaneko Seeds, Japan | Cultivar | 70.9 | Late | Introduced from another country | |

| 55 | Hanamiwase | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 27.4 | Extremely early | 1996 | From ‘Minamiaoba’ (30), ‘Tachiwase’ (57) and ‘Sakurawase’ |

| 56 | Yayoiwase | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 30.9 | Extremely early | 2015 | |

| 57 | Tachiwase | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 49.4 | Early | 1985 | From ‘Waseaoba’ (1), ‘Tottori Zairai’ (68) and ‘Miyazaki Zairai’ (69) |

| 58 | Tachimasari | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 52.4 | Early | 1989 | From ‘Waseaoba’ (1), ‘Waseyutaka’ (34), ‘Tottori Zairai’ (68) and ‘Miyazaki Zairai’ (69) |

| 59 | SI-14 | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 52.4 | Early | 2014 | From ‘Parental Line Nou 3’ (13) and other breeding lines |

| 60 | Tachimusha | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 59.6 | Medium | 1994 | From ‘Yamaaoba’ (35), ‘Tachiwase’ (57) and ‘Gulf’ (88) |

| 61 | Dryann | Snow Brand Seed, Japan | Cultivar | 62.1 | Medium | 1996 | From ‘Yamaaoba’ (35), ‘Tachiwase’ (57), ‘Tachimasari’ (58) and ‘Gulf’ (88) |

| 62 | Wasehudo | Takii, Japan | Cultivar | 40.3 | Extremely early | 1998 | From ‘Haruaoba’ (originated from ‘Tottori Zairai’ [68], ‘Miyazaki Zairai’ [69] and ‘Kuroishi Zairai’ [70]) and 2 breeding lines |

| 63 | Harutachi | NFACA, Japan | Cultivar | 65.3 | Late | Introduced from another country | |

| 64 | Green First | NFDCA, Japan | Cultivar | 60.8 | Medium | Introduced from another country | |

| 65 | Wase Up | Nihon Sogyo, Japan | Cultivar | 53.6 | Early | Introduced from another country | |

| 66 | Waseou | Nihon Sogyo, Japan | Cultivar | 50.4 | Early | Introduced from another country | |

| 67 | Ibaraki Zairai | NLBC Ibaraki Station, Japan | Landrace | 57.3 | Medium | ||

| 68 | Tottori Zairai | NLBC Tottori Station, Japan | Landrace | 54.6 | Early | ||

| 69 | Miyazaki Zairai | NLBC Miyazaki Station, Japan | Landrace | 62.6 | Medium | ||

| 70 | Kuroishi Zairai | KARC/NARO, Japan | Landrace | 58.9 | Medium | ||

| 71 | Kochi Zairai | NLBC Kochi Station, Japan | Landrace | 60.1 | Medium | ||

| 72 | Shiga Zairai | Shiga Prefectural College, Japan | Landrace | 68.5 | Late | ||

| 73 | Shikoku Zairai | WARC/NARO, Japan | Landrace | 59.7 | Medium | ||

| 74 | 08-KK-02 | Collection from Kagoshima, Japan | Ecotype | 61.3 | Medium | ||

| 75 | 08-KK-05 | Collection from Kagoshima, Japan | Ecotype | 61.2 | Medium | ||

| 76 | 08-KK-08 | Collection from Kagoshima, Japan | Ecotype | 58.9 | Medium | ||

| 77 | R.V.P. | Belgium | Cultivar | 66.5 | Late | ||

| 78 | Dasas | Denmark | Cultivar | 68.3 | Late | ||

| 79 | Baroldi | Netherlands | Cultivar | 73.5 | Late | ||

| 80 | Tur | Poland | Cultivar | 70.7 | Late | ||

| 81 | Midmar | South Africa | Cultivar | 72.9 | Late | ||

| 82 | Imperial | Sweden | Cultivar | 67.1 | Late | ||

| 83 | Axis | Switzerland | Cultivar | 70.1 | Late | ||

| 84 | Aber Marino | United Kingdom | Cultivar | 69.4 | Late | ||

| 85 | Magnolia | United States | Cultivar | 52.9 | Early | ||

| 86 | Stonevill Rust Resistant | United States | Cultivar | 70.1 | Late | ||

| 87 | Marshall | United States | Cultivar | 70.6 | Late | ||

| 88 | Gulf | United States | Cultivar | 62.7 | Medium | Commercial cultivar sold in Japan | |

| 89 | CPI26071 | Australia | Ecotype | 70.0 | Late |

- Abbreviations: CARC/NARO, Central Region Agricultural Research Center Hokuriku Research Station, NARO; ILGS/NARO, Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science, NARO; IPLRC, Ibaraki Prefectural Livestock Research Center; JGAFSA, Japan Grassland Agriculture and Forage Seed Association; KARC/NARO, Kyushu Okinawa Agricultural Research Center, NARO; NAES, Niigata Agricultural Experiment Station; NFACA, National Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations; NFDCA, National Federation of Dairy Cooperative Associations; NLBC, National Livestock Breeding Center; WARC/NARO, Western Region Agricultural Research Center, NARO; YPAFGTC, Yamaguchi Prefectural Agriculture and Forestry General Technology Center.

- a Investigated at Nasushiobara, Japan, in 2020 (days after March 1).

- b Assigned according to heading date (days after March 1) as extremely early, <49; early, 49–56; medium, 56–63; late, >63. Maturity types of Accessions 7, 8 and 29 were determined from our unpublished data.

- c Cited from data of Japanese PVP or published literature or unpublished information from authors involved in the breeding.

2.2 DNA preparation, sequencing and calculation of allele frequency

Sampling methods for DNA preparation followed the method of Byrne et al. (2013). For germination, 0.5 g of seeds from each accession was put on wet filter paper in a rectangular plastic plate (14 cm × 10 cm) and incubated under light at 25°C for 8–10 days. Then, 2-cm fragments of shoots >1 cm above the seeds were cut and gathered in one bulk. If fewer than 100 seeds germinated, additional seeds were germinated to add to the bulk. Thus, each shoot bulk originated from 100–200 individuals, with the exception that only 22 ‘ILW1’ plants were used. DNA was isolated with a Plant DNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For ‘QM16’, ‘QM19’ and ‘Niigatakei’, three DNA samples per accession were prepared as biological replicates. A GRAS-Di library was prepared for all 98 pooled-DNA solutions by Bioengineering Lab. Co., Ltd. Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan), under license. The library was constructed by two sequential PCR steps as described in Ito et al. (2020). For ‘Waseaoba’, four libraries from one DNA solution were prepared as technical replicates. Sequence data of paired reads (150 bases × 2) were obtained on a NextSeq 500 sequencer (Illumina) by Bioengineering Lab. Co. A list of unique sequences and read numbers was generated in GRAS-Di software (v. 1.0.3, Toyota, Aichi, Japan). The sequences were mapped to L. multiflorum 130 k scaffolds (Knorst et al., 2019) as a reference genome using BWA (Li & Durbin, 2010). Sequences with mapping quality ≥20 were filtered using SAMtools (Li et al., 2009). The output SAM file was split by the mapped scaffold, and the unique sequences mapped to overlapping genomic regions were assigned to the same genomic loci by our own “awk” script. Loci with read depth (DP) ≥ 15 for >75% of samples (n = 74) were selected, and allele frequency (read number of unique sequences ÷ DP at each locus) was calculated for each sample, except for samples with DP < 15. Unique sequences with an average minimal allele frequency of >0.03 at polymorphic (SNP, indel or combinations of both, i.e., haplotypes) loci were selected, and allele frequency and number of alleles per locus were recalculated.

2.3 Analysis of genetic diversity among or within accessions

Nei's standard genetic distance (DST; Nei, 1972) as a measure of genetic diversity between two populations (e.g., cultivars) and expected heterozygosity (HE; Nei, 1973) as a measure of genetic diversity within a population were calculated from all allele frequency data by using our own Python scripts. The values of replicates were averaged; analysis of variance was performed for pairwise DST within and between four types of accessions—Japanese cultivars (n = 38), Japanese breeding lines (n = 29), Japanese landraces and ecotypes (n = 10) and other countries' accessions (n = 12); and then, the means were compared. Hierarchical cluster analysis based on DST was conducted by the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) with the hclust function in R software (R Core Team, 2020). Using allele frequency data of loci without missing data, we conducted principal component analysis (PCA) using the prcomp function in R except for ‘ILW1’. k-means clustering, a nonhierarchical cluster analysis, was conducted using the scikit-learn library (Pedregosa et al., 2011) in Python with the same allele frequency data as PCA. k-means was performed 100 times, with k = 2 following the results of UPGMA and PCA.

2.4 Evaluation of heading date

Young seedlings grown in a greenhouse for 30–40 days were transplanted into the field nursery of the Nasushiobara Research Station, NARO (36°55′N, 139°56′E), on October 24, 2019. Seven or eight seedlings per accession were planted in line at a spacing of 80 cm × 50 cm with two replicates in a randomized block design. Fertilizer was applied at 8 g N/m2, 3.5 g P/m2, 6.6 g K/m2 before transplanting and at 2 g N/m2, 0.87 g P/m2, 1.7 g K/m2 on February 14, 2020. Dates when the tips of ≥3 inflorescences per plant appeared from the flag leaf sheath were recorded. ‘BMS1’, ‘BMS2’ and ‘Tomokei 32’ were not field tested, so their maturity types were judged from data of previous field tests (data not shown).

2.5 Statistical analysis

All other statistical analyses were performed in JSPS software (JASP Team, 2020).

3 RESULTS

3.1 GRAS-Di analysis in the Italian ryegrass population

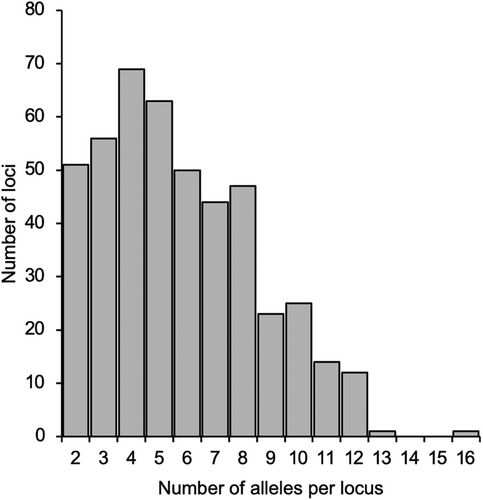

GRAS-Di analysis of the pooled DNA obtained 47,976,782 raw reads (average 489,559 per sample). Out of 67,058 unique sequences, 36,819 were mapped at 10,412 loci on the reference genome. Finally, 2629 unique sequences (alleles) at 456 reliable polymorphic loci were screened. The average sequence length was 141.3 bases (min. 50 to max. 200). Out of the 456 loci, 427 (93.6%) were each mapped on a unique scaffold, but in 13 cases (5.7%), two loci were mapped on the same scaffold, and in one case (0.7%), three loci were mapped on the same scaffold. The average number of loci for the genetic diversity analysis in each sample ranged from 196 (‘ILW1’) to 455 (‘Tachimasari’), with a mean of 412. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the number of alleles per locus in this population. The average number was 5.8 in the population and 4.4 in each sample.

3.2 Genetic diversity among Italian ryegrass accessions

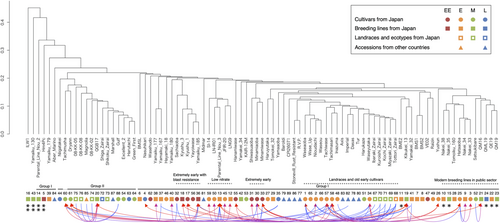

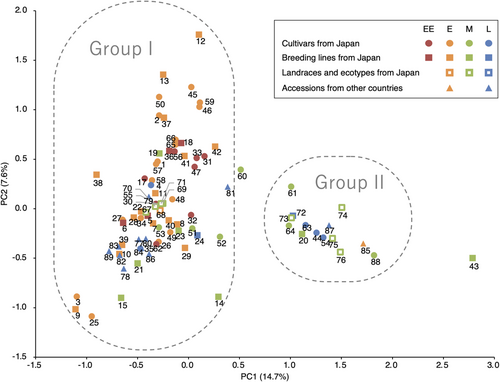

We calculated the genetic diversity between all pairs of accessions from the allele frequency in the pooled DNA. The effect of accession type on pairwise DST was significant (P < 0.001): The mean DST within Japanese breeding lines was significantly higher than those within the other three types, and those between Japanese breeding lines and other types were also significantly higher than those between the other types (P < 0.05, Table S1). On the other hand, there was no significant difference in the mean DST within or between Japanese cultivars, Japanese landraces and ecotypes and other countries' accessions, except between that within Japanese landraces and ecotypes and that between Japanese cultivars and other countries' accessions. Figure 2 shows a UPGMA dendrogram based on DST calculated from allele frequencies at the 456 loci with maturity type judged from field tests and kinship based on breeding history (Table 1). Accessions presumed to be closely related on the basis of breeding history tended to show closer affinities than others (Figure 2). All samples within each biological or technical replicate (four in all) clustered together (data not shown). Fifteen accessions including ‘Gulf’ formed a subgroup: It included cultivars, landraces and ecotypes from both Japan and overseas with mainly medium maturity (Figure 2). PCA was conducted based on the frequencies of 404 alleles at 83 loci without missing values (except for ‘ILW1’). The first and second PCs explained 14.7% and 7.6% of the variance (Figure 3). The first PC seemed to split the population into two groups as suggested by the hierarchical clustering: accessions with >0.5 of the first PC score were consistent with the 15 accessions that formed a subgroup in the hierarchical clustering, except for ‘Yamaiku 130’ (Figures 2 and 3). Following the results of hierarchical clustering and PCA, k-means clustering was conducted at k = 2 using the same data as PCA. The clustering result obtained with highest frequency split the population into a large group with 73 accessions and a small group with 15 accessions: The small group corresponded to the subgroup in the hierarchical clustering (named group II here: the other is group I) with the exception that that ‘Yamaiku 130’ assigned to the small group by k-means was not included in the subgroup in the hierarchical clustering; and ‘Tachimusha’ was assigned conversely (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Acc. No. | Acc. name | HE | A | Group | Acc. No. | Acc. name | HE | A | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Waseaoba | 0.562 | 4.78 | I | 46 | Hayamaki 18 | 0.495 | 4.06 | I |

| 2 | Nioudachi | 0.529 | 4.37 | I | 47 | VE02 | 0.525 | 4.56 | I |

| 3 | Nakei 33 | 0.504 | 4.22 | I | 48 | Inazuma | 0.561 | 4.83 | I |

| 4 | Nasuhikari | 0.500 | 3.87 | I | 49 | Raizin | 0.542 | 4.83 | I |

| 5 | Hm4Pc | 0.385 | 3.09 | I | 50 | LN-IR01 | 0.510 | 4.04 | I |

| 6 | BMSL | 0.509 | 3.89 | I | 51 | Harukaze | 0.586 | 5.24 | I |

| 7 | BMS1 | 0.535 | 4.48 | I | 52 | Satsukibare | 0.560 | 4.94 | I |

| 8 | BMS2 | 0.535 | 4.39 | I | 53 | KAIR-12M | 0.505 | 4.22 | I |

| 9 | Nakei 34 | 0.509 | 4.35 | I | 54 | Excellent 2 | 0.573 | 5.02 | II |

| 10 | Nakei 38 | 0.538 | 4.43 | I | 55 | Hanamiwase | 0.509 | 4.15 | I |

| 11 | BME2 | 0.552 | 4.82 | I | 56 | Yayoiwase | 0.518 | 4.40 | I |

| 12 | LNG9 | 0.434 | 3.49 | I | 57 | Tachiwase | 0.549 | 4.83 | I |

| 13 | Parental Line Nou 3 | 0.475 | 3.62 | I | 58 | Tachimasari | 0.551 | 4.82 | I |

| 14 | Parental Line Nou 2 | 0.360 | 2.95 | I | 59 | SI-14 | 0.519 | 4.29 | I |

| 15 | Nakei 35 | 0.517 | 4.13 | I | 60 | Tachimusha | 0.515 | 4.23 | I or IIb |

| 16 | ILW1 | 0.290 | 2.54 | – | 61 | Dryann | 0.512 | 4.33 | II |

| 17 | Kyushu 1 | 0.538 | 4.39 | I | 62 | Wasehudo | 0.507 | 4.38 | I |

| 18 | Kyushu 3 | 0.521 | 4.30 | I | 63 | Harutachi | 0.589 | 5.22 | II |

| 19 | Kikukei 13 | 0.535 | 4.48 | I | 64 | Green First | 0.588 | 5.21 | II |

| 20 | QGB17 | 0.543 | 4.38 | II | 65 | Wase Up | 0.546 | 4.67 | I |

| 21 | QM16 | 0.537a | 4.56a | I | 66 | Waseou | 0.551 | 4.68 | I |

| 22 | QE19 | 0.551 | 4.87 | I | 67 | Ibaraki Zairai | 0.564 | 4.88 | I |

| 23 | QM19 | 0.572a | 4.96a | I | 68 | Tottori Zairai | 0.565 | 4.88 | I |

| 24 | QML19 | 0.571 | 4.91 | I | 69 | Miyazaki Zairai | 0.568 | 4.84 | I |

| 25 | Hataaoba | 0.512 | 4.35 | I | 70 | Kuroishi Zairai | 0.550 | 4.57 | I |

| 26 | Yushun | 0.507 | 4.35 | I | 71 | Kochi Zairai | 0.577 | 4.97 | I |

| 27 | Haruyutaka | 0.518 | 4.25 | I | 72 | Shiga Zairai | 0.563 | 4.87 | II |

| 28 | Tomoiku 160 | 0.541 | 4.53 | I | 73 | Shikoku Zairai | 0.555 | 4.72 | II |

| 29 | Tomokei 32 | 0.508 | 4.51 | I | 74 | 08-KK-02 | 0.541 | 4.64 | II |

| 30 | Minamiaoba | 0.542 | 4.65 | I | 75 | 08-KK-05 | 0.504 | 4.13 | II |

| 31 | Shiwasuaoba | 0.510 | 4.35 | I | 76 | 08-KK-08 | 0.521 | 4.38 | II |

| 32 | Sachiaoba | 0.489 | 4.09 | I | 77 | R.V.P. | 0.536 | 4.51 | I |

| 33 | Minamiwase | 0.498 | 3.93 | I | 78 | Dasas | 0.565 | 4.85 | I |

| 34 | Waseyutaka | 0.578a | 4.90a | I | 79 | Baroldi | 0.502 | 4.22 | I |

| 35 | Yamaaoba | 0.530 | 4.52 | I | 80 | Tur | 0.570 | 4.80 | I |

| 36 | Yamaiku 185 | 0.519 | 4.19 | I | 81 | Midmar | 0.517 | 4.22 | I |

| 37 | Yamaiku 167 | 0.481 | 4.12 | I | 82 | Imperial | 0.549 | 4.63 | I |

| 38 | Yamaiku 177 | 0.482 | 4.38 | I | 83 | Axis | 0.542 | 4.55 | I |

| 39 | Yamaiku 179 | 0.446 | 3.48 | I | 84 | Aber Marino | 0.494 | 3.96 | I |

| 40 | Yamaiku 180 | 0.523 | 4.33 | I | 85 | Magnolia | 0.529 | 4.45 | II |

| 41 | Yamakei 32 | 0.533 | 4.6 | I | 86 | Stonevill Rust Resistant | 0.538 | 4.45 | I |

| 42 | Yamakei 34 | 0.512 | 4.05 | I | 87 | Marshall | 0.541 | 4.54 | II |

| 43 | Yamaiku 130 | 0.414 | 3.3 | I or IIb | 88 | Gulf | 0.508 | 4.27 | II |

| 44 | Niigatakei | 0.499a | 4.01a | II | 89 | CPI26071 | 0.537 | 4.66 | I |

| 45 | JFIR-20 | 0.505 | 4.16 | I |

- a Mean values among replicates.

- b Accession 43 was assigned to group I by UPGMA and to group II by k-means method. Accession 60 was assigned conversely.

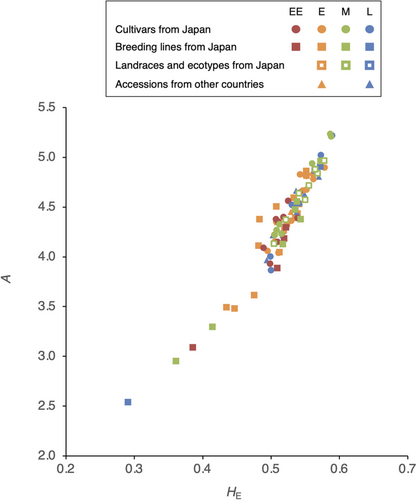

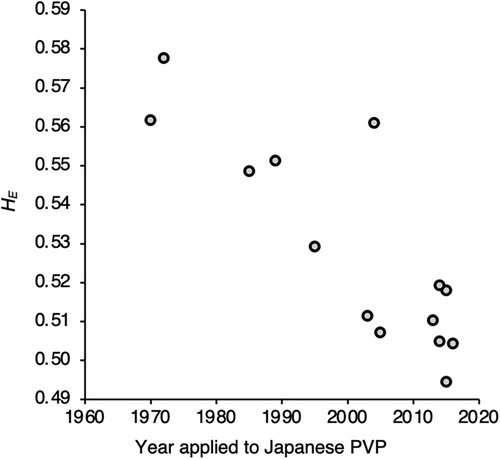

3.3 Genetic diversity within each Italian ryegrass accession

Mean expected heterozygosity (HE) and mean number of alleles per locus (A) over all loci of each accession are shown in Table 2 and Figure 4. Coefficients of variation among replicates were 0.5% to 1.8% in HE and 1.0% to 4.4% in A. HE ranged from 0.290 (‘ILW1’) to 0.589 (‘Harutachi’), and A ranged from 2.54 (‘ILW1’) to 5.24 (‘Harukaze’). Among the Japanese cultivars, HE ranged from 0.489 (‘Sachiaoba’) to 0.589 (‘Harutachi’) and A from 3.87 (‘Nasuhikari’) to 5.24 (‘Harukaze’). HE and A were significantly correlated (Pearson's correlation coefficient; r = 0.955, P < 0.001). There was no significant correlation between heading date and HE or A. A significant negative correlation (P < 0.05) was observed between the year of application and HE of the 29 cultivars registered in the Japanese PVP (r = −0.373, P = 0.046) but not between A and the year of application (r = −0.271, P = 0.154); however, there was a more significant negative correlation for 14 early-maturing cultivars on both indices (r = −0.855, P < 0.001, Figure 5; r = −0.840, P < 0.001, respectively).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Validity of the genotyping method in this study

We used GRAS-Di analysis of pooled DNA to genotype heterogeneous and heterozygous populations and analyzed the genetic diversity among and within populations (=accessions) on the basis of the allele frequencies. For bulk analysis, ≥48 individuals are recommended to represent a ryegrass cultivar for exploration of relationships and genetic diversity using a pooled-DNA approach (Pembleton et al., 2016); we use pooled DNA from 100 to 200 individuals for genotyping. The genetic distances among replications used for four accessions were small enough to form an isolated cluster, and the variation of within-population diversity was also small (0.8% to 4.4%). These results support the validity of our sampling methods and the stability of GRAS-Di. The fact that the genetic distances of cultivars that were presumed to be closely related on the basis of breeding history were small (Figure 2) also supports the validity of the methods. However, analysis of closer genetic relationships may require more replications of DNA pools.

We used published scaffold-level genome sequences for reference. Accession ‘ILW1’, derived from six rounds of self-pollination of a single heterozygous individual and used as a check here, had the lowest values of HE and A, but they were larger than expected (theoretical expected HE is 0.008 even if it is derived from a plant completely heterozygous at all investigated loci). This discrepancy may reflect the low accuracy of the mapping. In addition, only 55% of the unique sequences obtained by GRAS-Di could be mapped. The use of a high-quality reference genome sequences will be important for further analysis of Italian ryegrass diversity.

4.2 Genetic diversity and structure related to breeding history in Japan

Cluster analyses and PCA divided Japanese diploid Italian ryegrass cultivars and breeding materials into two major groups as indicated in Figures 2 and 3 and Table 2: group I, a large population that includes most of the Japanese cultivars, and group II, a small group with mainly medium maturity. The grouping results of ‘Yamaiku 130’ and ‘Tachimusha’ differed depending on the analysis method; it may be due to the difference in the data sets used. We discuss the relationship between the results and the breeding history in each group.

Full-scale breeding in Japan began with landraces derived from cultivars introduced from overseas and multiplied at public stud farms (Table 1). Five such landraces (‘Ibaraki Zairai’, ‘Tottori Zairai’, ‘Miyazaki Zairai’, ‘Kuroishi Zairai’ and ‘Kochi Zairai’) show very close kinship (Figure 2). This suggests that they were derived from a common ancestor, which may be closely related to other foreign cultivars in group I (Figure 2). From the 1970s to the 1980s, ‘Waseaoba’ (Yoshioka et al., 1971), ‘Waseyutaka’ (Kinoshita et al., 1973), ‘Tachiwase’ and ‘Tachimasari’ were bred with the goals of early maturity, erect stature with lodging tolerance and high yield. They were placed in the same cluster as their parent landraces (Figure 2). These early-maturing cultivars still have a high market share in Japan today.

Since 1977, when ‘Minamiwase’ (Kinoshita, 1977) was bred from landraces and foreign cultivars, extremely early-maturing cultivars have been bred to enable double cropping, allowing time for summer crop in warm regions. The hierarchical cluster analysis confirms the close relationship of ‘Minamiwase’ and its selections, ‘Minamiaoba’ and ‘Siwasuaoba’. Extremely early-maturing cultivars can be harvested before the end of the year, but they need to be sown in late summer, which requires blast resistance (Arakawa, 2021). Such cultivars have been bred from ‘Sachiaoba’ (Mizuno et al., 2003). They formed a cluster separate from another extremely early cluster (Figure 2), suggesting different genetic backgrounds.

Since the 2000s, to reduce the risk of nitrate poisoning in cattle, breeding to reduce the nitrate-N content in Italian ryegrass has been conducted in Japan (Harada et al., 2003). As a parental line, ‘Parental Line Nou 3’, with low-nitrate content, was bred from early-maturing cultivars in group I, and then, three cultivars were bred by crossing a breeding line selected from ‘Parental Line Nou 3’ with high-yield breeding lines or cultivars. They and ‘LNG9’, further selected from ‘Parental Line Nou 3’ for low nitrate-N, formed a cluster and are distinguished from each other by the second PC. This structure suggests that the influence of the low-nitrate parental breeding line is significant in the genetic background, and these accessions have a unique allele frequency structure.

In recent years, public breeding of diploid Italian ryegrass has been carried out at the NARO Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science (NILGS) and the Kyushu Okinawa Agricultural Research Center (KARC). Breeding materials in these institutions were derived from very diverse breeding lines and cultivars (Table 1), and they were closely related to each other in group I by clustering analysis, as ‘Nakei 33’, ‘Nakei 34’, ‘Nakei 35’ and ‘Nakei 38’ in NARO/NILGS and ‘QM16’, ‘QE19’, ‘QM19’ and ‘QML19’ in NARO/KARC (Figure 2).

One of the group II accessions, ‘Gulf’, was introduced from Uruguay into the United States and registered with the OECD in 1958. ‘Gulf’ is grown in Japan and accounts for one third of the total Italian ryegrass seed distribution in Japan (Japan Livestock and Seed Association, unpublished data), mainly on account of its low seed price. Because of its widespread use in Japan, it is likely that the ecotypes and landraces in Japan assigned to group II are derived from ‘Gulf’ or closely related foreign cultivars. ‘Dryann’ and ‘Tachimusha’ (assigned to group II by hierarchical clustering only) were domestically bred cultivars having ‘Gulf’ as one of their parental material, which is consistent with the fact that they were assigned in this group. ‘Yamaiku 130’ was classified as group II by nonhierarchical clustering, but it was distantly related to the group II cluster in the hierarchical clustering, maybe because ‘Yamaiku 130’ is a ‘Gulf’-derived line, but was obtained by selfing one or a few genotypes (personal communication from the breeder).

Many group II accessions, with the exception of ‘Dryann’ and ‘Tachimusha’, have an open-book morphology, unlike the erect morphology of Japanese cultivars in group I (Tase & Kobayashi, 1994; our unpublished data). However, many landraces and foreign cultivars in group I also have the open-book form. In addition, group I includes accessions with medium to late maturity. These differences suggest that the genetic structure of the Japanese diploid Italian ryegrass population revealed here cannot be determined from morphological characteristics or earliness but can be determined only by using molecular tools. Guan et al. (2017) classified 122 L. multiflorum genotypes from 41 cultivars collected worldwide into three subgroups on the basis of SSR marker polymorphisms. Among them, ‘Gulf’, ‘Tur’ and ‘Midmar’ overlapped with our materials; ‘Gulf’ and ‘Tur’ belonged to different subgroups, consistent with our results, while ‘Midmar’ belonged to different subgroups according to genotype.

Four accessions—‘ILW1’, ‘Parental Line Nou 2’, ‘Hm4PC’ and ‘Yamaiku 179’—were distantly related to other accessions (most of accessions in group I and group II) and to each other by hierarchical clustering (Figure 2). ‘ILW1’, ‘Parental Line Nou 2’ and ‘Hm4PC’ were derived from only one to three individuals and showed low genetic diversity (Table 2). They have unique alleles, which is the reason for the large genetic distance between them and other accessions. We think that the greater genetic diversity within Japanese breeding lines than within other types is due to the inclusion of diverse accessions, including these experimental lines. On the other hand, there was little significant difference in genetic diversity within or between the other accession types, which suggests that these types are genetically related to each other: That is, the Japanese cultivars are derived from foreign cultivars and Japanese landraces, which in turn originated from foreign cultivars.

4.3 Genetic diversity related to use in breeding

In the breeding of allogamous Italian ryegrass, it is important to maintain genetic diversity while ensuring a degree of homogeneity within the cultivar. We have found a significant decrease in genetic diversity within early-maturing cultivars over the past 60 years of breeding in Japan (Figure 5). This decrease may be attributed to the reliance on a limited gene pool and the increased selection pressure in recent years by targeting specific traits such as low-nitrate content. In general, yield is most important, and new cultivars yield the same as or more than existing cultivars. Therefore, early-maturing cultivars in Japan have maintained yields with decreasing genetic diversity. However, any further reduction in genetic diversity may inhibit future efforts to improve yield and wide environmental adaptability. To maintain or increase genetic diversity within a cultivar, the genetic diversity profile of breeding materials obtained here will be an important tool. In particular, accessions in group II, which were suggested to be genetically distant from the major breeding material population in group I, can be used to maintain and expand genetic diversity. As a practical example, in the recent diploid Italian ryegrass breeding at KARC/NARO, accessions in group II, such as ‘08-KK-08’, have been introduced into breeding lines ‘QE19’, ‘QM19’ and ‘QML19’ (Table 1). In fact, among breeding lines with medium maturity, HE and A of ‘QM19’, bred in 2019, were significantly greater than those of ‘QM16’ bred in 2016, which corresponds to the previous generation of ‘QM19’ (Table 2; P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively, t test). The construction of more detailed diversity profiles of more diverse breeding materials and cultivars will contribute to the advancement of Italian ryegrass breeding.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Genetic diversity among and within Japanese diploid Italian ryegrass cultivars and breeding materials was analyzed by using allele frequency data obtained by GRAS-Di analysis of pooled DNA. Cluster analysis and PCA divided the accessions into two groups: a large group including major domestic cultivars and landraces as their ancestors and a small group including the major introduced cultivar ‘Gulf’. The genetic relationships indicated fully reflect the kinship inferred from the breeding history. We expect that the genetic relationships will help to maintain or increase diversity within the breeding population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Dr. Kenji Okumura for his generous support during the study.