Pharmacological treatment for mental health illnesses in adults receiving dialysis: A scoping review

Jenny Wichart and Peter Yoeun should be considered joint first authors.

Abstract

Background

Pharmacologic management of mental health illnesses in patients receiving dialysis is complex and lacking data.

Objective

Our objective was to synthesize published data for the treatment of depression, bipolar and related disorders, schizophrenia or psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders in adults receiving hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

Methods

We undertook a scoping review, searching the following databases: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science. Data on patients who received only short-term dialysis, a kidney transplant, or non-pharmacologic treatments were excluded.

Results

Seventy-three articles were included: 41 focused on depression, 16 on bipolar disorder, 13 on schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, 1 on anxiety disorders, and 2 addressing multiple mental health illnesses. The majority of depression studies reported on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as a treatment. Sertraline had the most supporting data with use of doses from 25 to 200 mg daily. Among the remaining SSRIs, escitalopram, citalopram, and fluoxetine were studied in controlled trials, whereas paroxetine and fluvoxamine were described in smaller reports and observational trials. There are limited published data on other classes of antidepressants and on pharmacological management of anxiety. Data on treatment for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and related disorders are limited to case reports.

Conclusion

Over half of the studies included were case reports, thus limiting conclusions. More robust data are required to establish effect sizes of pharmacological treatments prior to providing specific recommendations for their use in treating mental health illnesses in patients receiving dialysis.

Abbreviations

-

- BDI

-

- Beck Depression Inventory

-

- BDI-II

-

- Beck Depression Inventory-II

-

- CANMAT

-

- Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments

-

- CBT

-

- cognitive behavioral therapy

-

- CKD

-

- chronic kidney disease

-

- HAM-D

-

- Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

-

- HD

-

- hemodialysis

-

- ISBD

-

- International Society of Bipolar Disorders

-

- QoL

-

- quality of life

-

- PD

-

- peritoneal dialysis

-

- RCT

-

- randomized controlled trial

-

- SAMe

-

- S-adenosyl-L-methionine

-

- SF-36

-

- Short Form-36

-

- SNRI

-

- serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

-

- SSRI

-

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

-

- TCA

-

- tricyclic antidepressant

1 INTRODUCTION

Of the 4 million Canadians living with kidney disease, more than 48 000 live with kidney failure, and approximately 30 000 receive a form of dialysis for kidney replacement therapy [1, 2]. Depression and anxiety are more common in patients receiving dialysis compared to the general population, up to 20–30% and 17–46%, respectively [3-7]. People living with mental health illnesses, including schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, also have a higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) [7]. Importantly, mental health illnesses diagnosed in patients receiving dialysis have a negative impact on quality of life (QoL) and overall prognosis [5, 8-10]. People receiving dialysis treatment while living with mental health illnesses further suffer the inequity of receiving suboptimal kidney care and may be less likely to receive a kidney transplant [7, 11].

Despite the high prevalence of mental health illnesses in patients receiving dialysis, treatment is generally poor, both in Canada and globally [7, 9, 12]. Diagnosis may be confounded by the significant overlap of somatic symptoms of kidney failure with symptoms of mental health illnesses such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, fear, dread, and anorexia [9]. Mental health illnesses are thus under-detected and undertreated [6]. Even with a diagnosis of depression, it has been reported that only 17–42% of patients receiving dialysis were treated [4, 13]. Monitoring and follow-up also appear to be poor. Guirguis et al. showed that although two-thirds of treated patients receiving dialysis had worsened depression scores on follow-up, only 27% had changes made to their treatment, such as dose escalation [14].

Many medications used to treat mental health illnesses have limited evidence for patients receiving dialysis. Since medications excreted by the kidneys pose an increased risk for adverse effects in this patient population, they are often avoided or given at suboptimal doses, thus limiting treatment options [14, 15]. Adding to the complexity of medication dosing, dialysis may also affect medication clearance [15].

Treating mental health illnesses for patients receiving dialysis can be a daunting task given the complexity of the diagnosis and the limited evidence for efficacy and safety of medication dosing. This scoping review was undertaken as part of a larger project to develop a pathway for mental health care for Albertans receiving dialysis [16]. The aim was to provide a summary of available pharmacological treatment options to facilitate safe, evidence-based treatment for mental health diagnoses or symptoms in patients receiving dialysis. The research questions guiding this review were as follows: (1) Which pharmacological treatments are recommended for treating mental health illnesses and symptoms experienced by patients receiving dialysis? (2) What are the recommendations regarding dosage of a specific pharmacological treatment?

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

We undertook a scoping review that followed the framework of Arksey and O'Malley [17], revised by Levac et al. [18]. Scoping reviews commonly “map” the extent and range of evidence available in the literature with the intent to show the breadth and depth of a topic [18]. Our review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [19], specifically the extensions for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and Searching (PRISMA-S).

2.2 Search strategy

A systematic literature search, created by an experienced health sciences librarian (MK), was conducted in the following bibliographic databases from inception to February 28, 2022: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO via OVID; Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCOhost; Scopus via Elsevier; Web of Science: Core Collection; and Cochrane Library via Wiley. These databases were searched using a combination of natural language vocabulary (keywords) and controlled terms (subject headings). Search terms were derived from three main concepts: (1) broad spectrum of mental health disorders; (2) drug therapy and known pharmaceutical interventions for controlling mental health disorders, including antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, mood-stabilizing medications, and antipsychotics; (3) CKD, Stage 3 and higher or end-stage, or dialysis. Results were limited to the adult population, and various publication types were removed, including conference materials, books and book chapters, editorials, and letters (see Data S1 for full search strategies by database).

Results from database searches were exported in complete batches on February 28, 2022. Records were imported to the systematic review management software, Covidence. This software was used to identify and remove duplicate records and facilitate title/abstract screening and full-text screening of records.

2.3 Selection criteria

Selection of publications was based on inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Table 1). Texts were required to focus on (a) dialysis modalities, (b) pharmacological treatment including details on dosage and kinetics, and (c) a persistent mental health illness or symptom(s).

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Setting |

All peer-reviewed study types All dialysis modalities (peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis) AND All types of pharmacological treatments that provide detailed guidance on dosage and kinetics AND Persistent/ongoing mental health conditions or symptoms,a including but not limited to depression and anxiety |

Studies targeting kidney populations not receiving dialysis (e.g., kidney transplant patients, pre-dialysis patients, patients receiving conservative care, and caregivers/family members of patients receiving dialysis) Studies reporting on short-term dialysis (e.g., for acute kidney injury to deal with overdose and intoxication) Studies reporting non-pharmacological treatment (e.g., acupuncture) Studies reporting on a medication without guidance for pharmacological treatment with patients receiving dialysis Studies focusing solely on pharmacokinetics |

| Sample |

Patients older than 18 years of age Human studies |

|

| Time frame | No limit | |

| Languages | All languages |

- a Mental health symptoms include depressed mood; changes in energy; confusion; sexual dysfunction; cognitive impairment; difficulty sleeping or excessive sleeping; changes in appetite and/or weight changes; feeling restless, wound up, or on edge; and so on.

2.4 Article selection

We used Covidence to assist 16 reviewers with screening titles, abstracts, and full texts. Reviewers worked in pairs that included at least one pharmacist. Discrepancies among reviewers were discussed for resolution, and the lead authors (JW, PY) were consulted when needed. Team members facilitated translation of the relevant parts of texts written in French, German, and Spanish.

2.5 Data extraction

Following the identification of eligible articles, data were extracted by 15 team members. Pairs consisted of at least one pharmacist; data were extracted by one team member and reviewed by the other. Data extraction for the eligible articles included the following predefined categories: author(s), publication year, patient sex, age, ethnicity, dialysis modality, mental health illness, comorbidities, study design, sample size, study outcome, drug name, dose, frequency, dosing pre- or post-dialysis, route of administration, length of intervention in days, reported adverse effects, and study results. Sample sizes were listed as intention-to-treat.

2.6 Data analysis

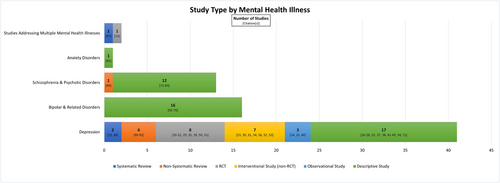

A descriptive narrative approach was used to summarize the literature, and only data for patients receiving dialysis were extracted. In Table 2, we present our full findings categorized by DSM-5 criteria for depression, bipolar and related disorders, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders. Table 3 lists antidepressants that were supported by randomized controlled trial (RCT) data. Publications organized by mental health illness and study design are presented in Figure 1.

| Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size | Drug regimen | Dialysis modality | Clinical outcomes and associated results |

| Mehrotra et al. (2019) [20] | Interventional study— RCT |

Sertraline: 60 CBT: 60 |

Sertraline 25 mg PO daily, titrated up to 200 mg PO daily, as tolerated. CBT × 12 weeks |

HD | Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms-Clinician-Rated (QIDS-C) score at 12 weeks was statistically significantly lower in the sertraline group compared to the CBT group. Authors note that AEs were more frequent in the sertraline group than the CBT group. |

| Friedli et al. (2017) [21] | Interventional study—RCT |

Sertraline: 15 Placebo: 15 |

Sertraline 50 mg PO daily, option to increase to 100 mg PO daily | HD | No statistical difference in Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and BDI-II scores between the two groups after 6 months, noting that this was a feasibility study for consideration prior to a larger RCT and recruitment issues identified. |

| Wang et al. (2016) [22] | Interventional study— RCT |

Cholecalciferol: 373 Placebo: 373 |

Cholecalciferol 50 000 units PO weekly × 1 year | HD, PD | No significant difference in the degree of change in BDI-II scores between the two groups; however, when the groups were divided into MDD and vascular depression, a difference was found with the latter. |

| Zhao et al. (2016) [23] | Interventional study— RCT |

Aerobic exercise: 63 Escitalopram: 63 Aerobic exercise plus escitalopram: 63 |

Escitalopram 20 mg PO daily | HD | Diagnostic criteria for depression not stated. After 18 weeks, QoL (based on SF-36) was improved in the aerobic activity plus escitalopram and aerobic activity groups when compared to the escitalopram group. The aerobic activity group had less patients with severe depression severity when compared to the escitalopram groups. |

| Dashti-Khavidaki et al. (2014) [24] | Interventional study— RCT |

Omega-3: 20 Placebo: 20 |

Omega-3 fatty acids 2 capsules (each capsule—180 mg eicosapentaenoic acid + 120 mg docosahexaenoic acid) PO TID with meals × 4 months | HD | Significant improvement in BDI and overall SF-36 scores when comparing omega-3 versus placebo. |

| Taraz et al. (2013) [25] | Interventional study—RCT |

Sertraline: 25 Placebo: 25 |

Sertraline 50 mg PO daily × 2 weeks, then 100 mg PO daily × 10 weeks | HD | When compared to placebo, sertraline showed a significant reduction in IL-6 (primary outcome) and additionally report statistically significant lower BDI-II scores at 12 weeks. |

| Blumenfield et al. (1997) [26] | Interventional study—RCT |

Fluoxetine: 7 Placebo: 7 |

Fluoxetine 20 mg PO daily | HD | Statistically significant changes in BDI, Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), and Electronic Visual Analog Scale seen at 4-week midpoint but not sustained at 8 weeks. |

| Zetin et al. (1982) [27] | Interventional study—RCT |

Amitriptyline: 8 Placebo: 8 |

Amitriptyline 50–200 mg PO HS × 13 weeks | HD | Compared to placebo, patients treated with amitriptyline showed no difference in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), HAM-D, Descriptive Adjective Check List, or physician depressive ratings after 13 weeks. |

| Tashiro et al. (2017) [28] | Interventional study |

L-carnitine: 16 Age-matched healthy controls: 16 |

L-carnitine 900 mg PO daily or 1000 mg IV post-HD, three times a week, over 3 months | HD | Patients receiving L-carnitine supplementation had significantly increased serum carnitine levels and decreased self-rating depression scale (SDS) scores at the end of the study period. |

| Cilan et al. (2012) [29] | Interventional study |

HD with depression: 9 Non-HD healthy control: 20 |

Sertraline 50 mg PO daily × 8 weeks | HD | In depressed patients receiving HD, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of measured cytokine levels after 8 weeks of sertraline treatment. It was noted that BDI, HAM-D, and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) scores did also significantly decrease in this group after 8 weeks. |

| Kalender et al. (2007) [30] | Interventional study |

HD: 68 CAPD: 47 CKD-conservative management: 26 |

Citalopram 20 mg PO daily × 8 weeks | HD, CAPD | 34/141 patients (24.1%) had depression and offered treatment with citalopram. After 8 weeks of citalopram 20 mg daily, there was a statistically significant reduction in mean BDI score and an increase in 2 subscales of the SF-36. |

| Koo et al. (2005) [31] | Interventional study |

Paroxetine: 34 Controls without depression: 28 |

Paroxetine 10 mg PO daily, plus supportive psychotherapy × 8 weeks | HD | In combination with psychotherapy, paroxetine resulted in a statistically significant improvement in HAM-D score when compared to baseline but not on the ZDS. There was no statistical difference in nutritional parameters between the 2 groups. |

| Lee et al. (2004) [32] | Interventional study | 28 | Fluoxetine 20 mg PO daily × 8 weeks | HD | Primary outcome of effect of fluoxetine on serum cytokine and nutritional status noted change in IL-1 beta and IL-6 only. Statistically significant decrease in HAM-D noted after 8 weeks. |

| Levy et al. (1996) [33] | Interventional study |

HD with depression: 6 Non-HD control with depression: 6 |

Fluoxetine 20 mg PO daily × 8 weeks | HD | Improvement in depression observed in both the HD and non-HD groups. AEs were similar between both groups. |

| Ancarani et al. (1993) [34] | Interventional study |

SAMe: 42 Placebo: 11 |

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) 400 mg IV on alternate days post-HD × 3 weeks | HD | Both SAMe and placebo resulted in statistically significant reduced scores on the Institute for Personality and Ability Testing-Depression Scale (IPAT-DS) at week 3 compared to baseline. Only SAMe resulted in a statistically significant reduced HARD scale score at week 3 compared to baseline. There were no reported between group comparisons. |

| Atalay et al. (2010) [35] | Observational study | 25 | Sertraline 50 mg PO daily × 12 weeks | PD | Sertraline is associated with improvement in BDI score and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) parameters. |

| Turk et al. (2006) [36] | Observational study | 40 | Sertraline 50 mg PO daily × 8 weeks | HD | QoL parameters assessed via SF-36, and BDI showed a statistically significant improvement after 8 weeks of sertraline therapy. |

| Kennedy et al. (1989) [37] | Observational study | 8 |

Desipramine 50–125 mg PO daily OR Mianserin 10–20 mg PO daily OR Maprotiline 50–100 mg PO HS × 7 weeks |

HD, PD | Five patients recovered from their depressive syndrome indicated by scores on the BDI and HAM-D decreasing to 18 or less. One patient clinically improved but did not meet criteria for recovery. Two patients did not complete the trial (1 patient received a kidney transplant, 1 patient experienced AEs). Individual dialysis modalities weren't specified. |

| Kauffman et al. (2021) [38] | Descriptive study | 4 | Fluoxetine 90–180 mg PO weekly | HD | Report of 4 patients transitioned from daily to weekly fluoxetine. All patients no longer met criteria for MDD and continued weekly fluoxetine at doses ranging from 90 to 180 mg after the 12-week study period. |

| Miyahara et al. (2021) [39] | Descriptive study | 1 | Mirtazapine 7.5 mg PO daily | HD | Mirtazapine decreased HAM-D score in 1 patient. Report stated sustained effect over 6 months. |

| Han et al. (2016) [40] | Descriptive study | 1 | Paroxetine 25 mg PO HS | HD | Study showed paroxetine-induced hypoglycemia. |

| Chander et al. (2011) [41] | Descriptive study | 12 | Sertraline 25 mg PO daily | HD | Sertraline 25 mg daily was not tolerated and discontinued in 11/12 patients within 3 weeks. |

| Schlotterbeck et al. (2008) [42] | Descriptive study | 1 | Mirtazapine 15–30 mg PO daily | HD | One patient had full remission of depression after 10 days. |

| Bjarnason et al. (2006) [43] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium carbonate 12.2 mmol PO three times a week post-HD × 8 months | HD | Resulted in stabilization of depression symptoms and 12-h blood levels of 0.7 mmol/L. |

| Kamo et al. (2004) [44] | Descriptive study | 7 | Fluvoxamine 50 mg PO HS × 28 days | HD | 5/7 patients had improvement in HAM-D scores; 4 of those patients had a 50% reduction on the HAM-D from baseline to end of follow-up. Two patients dropped out due to AEs. |

| Wang and Watnick (2004) [45] | Descriptive study | 1 | Sertraline 25–50 mg PO daily | Not specified | Patient self-reported symptoms of depression improved after three months. |

| Fukunishi et al. (2002) [46] | Descriptive study | 1 | Trazodone 100 mg PO daily | HD | Depressive symptoms resolved but trazodone stopped due to development of parkinsonian symptoms (cogwheel rigidity, akinesia, and gait disturbance). Improved within 1 week of drug discontinuation. |

| Seabolt et al. (2001) [47] | Descriptive study | 1 | Nefazodone: initial dose 50 mg PO BID, titrated to 150 mg PO BID | HD | HAM-D score decreased from 40 to 12 after 20 weeks of therapy. |

| Wuerth et al. (2001) [48] | Descriptive study | 22 |

Sertraline 25–100 mg PO daily OR Bupropion 100–250 mg PO daily OR Nefazodone 25–50 mg PO daily × 12 weeks |

PD | Pilot study to determine feasibility of overall depression diagnosis and treatment strategy. 11/22 patients successfully completed 12 weeks of therapy: 7 on sertraline, 2 on nefazodone, and 2 on bupropion. All 11 patients had improvement in BDI score. |

| Kunishima et al. (2000) [49] | Descriptive study | 1 | Amoxapine 30 mg PO TID | HD | Patient developed neuroleptic malignant syndrome within 1 week of amoxapine initiation and passed away soon after. |

| Fukunishi et al. (1998) [50] | Descriptive study | 1 | Amitriptyline 25 mg IV twice daily × 14 days then switched to maprotiline 75 mg PO daily | HD | Symptoms of depression decreased by day 14 and amitriptyline switched to maprotiline. Patient developed tremors 6 days after start of maprotiline and had a cardiac arrest 9 days after start. Maprotiline was discontinued. |

| Stiebel (1994) [51] | Descriptive study | 2 | Cases 1 and 2: methylphenidate 5 mg PO at 8 a.m. and at noon |

Case 1: HD Case 2: PD |

Case 1: clinical improvement was noted within 72 h. ZDS score decreased from 78 to 58. Increased frequency of heart palpitations (but patient had history of atrial fibrillation). Case 2: improvement was noted within 2 days. HAM-D score improved from 27 to 2 in 2 weeks. |

| Sunderrajan et al. (1985) [52] | Descriptive study | 1 | Nortriptyline 25 mg PO TID and 50 mg PO at bedtime | PD | Improvement in depression was noted with 25 mg TID dosing. After nortriptyline 50 mg was added at bedtime secondary to following target levels, patient developed severe respiratory alkalosis requiring intubation, which resolved after nortriptyline was discontinued. After the patient recovered, the same dose was restarted, and the patient experienced the same outcome of respiratory alkalosis requiring intubation. Nortriptyline was discontinued, but the patient developed pneumonia, sepsis, and passed away. |

| Haffke et al. (1978) [53] | Descriptive study | 1 | Imipramine 25 mg PO TID, titrated up to QID × 6 months | HD | Symptoms of depression fluctuated with gradual improvement. |

| Rosser (1976) [54] | Descriptive study | 3 | Amitriptyline 50–100 mg PO daily | HD | One patient had good recovery, a second had some improvement. A third patient continued to deteriorate and died from cardiac arrest. |

| Palmer et al. (2016) [15] | Systematic review | NR | N/A | HD | There is not enough evidence to support antidepressant use. Extrapolating research from the general population may not be appropriate given the differences in medication pharmacokinetics. |

| Nagler et al. (2012) [55] | Systematic review | NR | N/A | NR | Review includes studies in dialysis, and recommendations are general for CKD3 to CKD5. Limited evidence to suggest antidepressant efficacy. Authors suggest initiating an SSRI for moderate major depression and re-evaluating after 8–12 weeks. |

| Gregg et al. (2021) [56] | Non-systematic review | NR | N/A | HD | Inconsistent benefit of SSRIs. A trial of SSRIs may be considered in some individuals with depression. If acceptable to the patient, it is reasonable to try other nonpharmacologic therapies (CBT, exercise). |

| Gregg and Hedayati (2020) [57] | Non-systematic review | NR | N/A | HD, PD | Limited data to support SSRI use; however, judicious trial of sertraline with slow dose titrations and close monitoring may be warranted. |

| Shirazian et al. (2017) [58] | Non-systematic review | NR | N/A | HD, PD | Further data are required to make definitive recommendations. Authors support that SSRIs can be considered as first-line when treating depression. |

| Hedayati et al. (2012) [59] | Non-systematic review | NR | N/A | NR | Insufficient data to suggest benefit in ESKD. When trialing pharmacotherapy, consider selecting an SSRI with close monitoring of efficacy and adverse effects. |

| Bipolar & related disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size | Drug regimen | Dialysis modality | Clinical outcomes and associated results |

| Ng et al. (2021) [60] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Valproate sodium 500 mg PO daily AM and 1000 mg PO HS Olanzapine 5 mg PO BID |

HD | Stabilization of manic symptoms within 2 weeks of treatment with increased doses of valproate sodium and olanzapine. |

| Topp and Salisbury (2021) [61] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Lithium 600 mg PO three times a week post-HD Sodium valproate 1500–2500 mg PO daily Olanzapine 10–20 mg PO daily Clonazepam 0.5 mg PO TID |

HD | Case of manic relapse. Minimal response with sodium valproate 2500 mg/day, olanzapine 20 mg/day, and clonazepam. Lithium was added to therapy. At week 12, the patient was stable on lithium carbonate 600 mg PO three times a week post-HD with levels consistently within the target therapeutic range (0.4–0.6 mmol/L), sodium valproate 1000 mg BID, olanzapine 10 mg daily, and clonazepam 0.5 mg TID. |

| Chang and Ho (2020) [62] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium carbonate 400 mg PO three times a week post-HD | HD | Case of manic relapse. Remission of manic symptoms within 6 weeks of lithium initiation, with pre-HD levels ranging between 0.3–0.4 mmol/L. Patient's mental state remained stable over 2 years. |

| Engels et al. (2019) [63] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium 200 mg PO daily | HD | Stable improvement in bipolar depressive symptoms for 1 year. Target serum pre-HD lithium concentration of 0.6 mmol/L. |

| Xiong et al. (2018) [64] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Haloperidol 5 mg PO AM and 10 mg HS for a brief period Risperidone 2 mg PO HS to 2 mg BID for 3 weeks (overlapping with risperidone long-acting IM injection 25 mg biweekly for long term maintenance) |

HD |

Haloperidol was discontinued due to worsening dysphoria and possible tardive dyskinesia and changed to oral risperidone. Risperidone resulted in clinical improvement ameliorating psychotic features. Long-term follow-up showed stable mental status with no psychosis. |

| Chan et al. (2011) [65] | Descriptive study | 1 | Fluoxetine 20 mg PO daily × 3 years, changed to trazodone PO titrated to 100 mg/day and valproic acid PO titrated to 500 mg/day | HD | Fluoxetine discontinued due to GI bleeding, which ceased once fluoxetine was stopped. No further GI bleeding with initiation of trazodone and valproic acid. Patient's partner reported less mood episodes during the following year. |

| Kaufman (2010) [66] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lamotrigine 100 mg PO AM and 150 mg PO HS | HD | Case of hypomania. Symptoms responded to treatment with lamotrigine. |

| Knebel et al. (2010) [67] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium carbonate 600 mg PO three times a week post-HD | HD | Patient had improvement in manic symptoms over 2 years, with lithium levels maintained in the range of 0.6–0.8 mmol/L. After an episode of hypomania, the dose was increased to 900 mg. The lithium dose was reduced back to 600 mg due to supratherapeutic level and AEs. The levels stabilized and patient had improved mental status. |

| Gupta and Annadatha (2008) [68] | Descriptive study | 2 |

Case 1: Olanzapine 20 mg PO HS and valproate semi sodium PO titrated over 2 weeks to 2 g/day. Lorazepam 1 mg PO BID and 2 mg pre-HD was added and tapered off. Case 2: valproate 1250 PO daily, risperidone 1 mg PO BID |

HD |

Case 1: Case of bipolar affective disorder. Mood stabilization with olanzapine and valproate. Lorazepam was added to help calm the patient for HD sessions. Case 2: case of bipolar affective disorder that responded to increased dose of valproate 1250 mg daily and addition of risperidone. |

| Quentzel and Levine (1997) [69] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium 900 mg PO three times a week post-HD | HD | Within 10 days of lithium treatment, all manic and psychotic symptoms were stabilized. Pre-HD lithium serum concentrations were maintained in the 0.8–1.0 mEq/L range. |

| Grüner et al. (1991) [70] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium carbonate slow release 400 mg post-HD due to pre-HD levels | HD | Weekly average pre-HD lithium levels were 0.5–0.77 mEq/L. Aggressiveness ceased within a couple days, and delusions stopped after 2 weeks of treatment. Stable at three-year follow-up. |

| Flynn et al. (1987) [71] | Descriptive study | 1 | Purified lithium chloride 0.69–0.94 mEq/L provided intraperitoneally via CAPD | CAPD | Patient stabilized with dosing and mania improved after starting intraperitoneal lithium therapy. Serum lithium levels were followed with 1 mEq/L being targeted. The patient decompensated and passed away. |

| Lippman et al. (1984) [72] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium 300 mg PO three times a week post-HD | HD | Levels done periodically pre-HD (0.5–0.6 mEq/L). Lithium therapy resulted in a higher level of functioning and improved QoL. |

| Port et al. (1979) [73] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium carbonate 300–900 mg PO three times a week post-HD | HD | Improvement in psychotic symptoms and depression after 4 weeks. Pre-HD levels did not exceed the therapeutic range of 0.7–1.2 mEq/L. |

| Procci (1977) [74] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium carbonate 300 mg PO three times a week post-HD titrated to final dose of 600 mg PO three times a week post-HD | HD | Clinical remission of symptoms after 2 weeks that was maintained over 6-month observation. Pre-HD lithium levels were consistently between 0.7–0.79 mEq/L. |

| Oakley et al. (1974) [75] | Descriptive study | 1 | Lithium chloride 0.7–1 mEq/L in dialysate | HD | Lithium was added to dialysate due to patient vomiting oral dose. Patient experienced moderate severity myoclonic twitching at higher concentrations. Lithium successfully controlled bipolar symptoms. |

| Schizophrenia & psychotic disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size | Drug regimen | Dialysis modality | Clinical outcomes and associated results |

| De Donatis et al. (2020) [76] | Descriptive study | 1 | Long-acting aripiprazole 400 mg IM monthly | HD | Patient maintained a stable antipsychotic response. No psychotic relapse over nearly 2 years of follow-up. |

| Tourtellotte and Schmidt (2019) [77] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Risperidone 12.5–37.5 mg IM biweekly, then switched to 2 mg PO daily Divalproex sodium ER 1500 mg PO daily |

HD | Risperidone IM formulation was reduced by 12.5 mg increments due to AEs and switched to oral risperidone based on family preference. Psychiatric symptoms remained stable on both IM and PO formulations. |

| Turčin (2018) [78] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Aripiprazole 15 mg PO daily Sertraline 50 mg PO daily Lorazepam PO 1.25 mg AM, 2.5 mg PM |

HD | Combination of sertraline, aripiprazole, and lorazepam resulted in psychiatric stabilization in 15 days. Authors noted that post-HD timing of medications was important in success of therapy. |

| Iskandar et al. (2015) [79] | Descriptive study | 1 | Ziprasidone 40–80 mg PO BID | HD | Patient had two occurrences of severe neutropenia when ziprasidone 80 mg BID was continued upon initiation of HD. Both times, neutropenia resolved within 1 week of ziprasidone discontinuation. Neutropenia did not develop when the patient's ziprasidone dose was reduced to 40 mg BID prior to initiation of HD. |

| Samalin et al. (2015) [80] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Quetiapine up to 800 mg PO Clozapine 500 mg PO HS (titrated over 7 weeks) Paliperidone palmitate 75 mg IM, followed by 50 mg IM 1 week later, followed by 75 mg IM monthly |

HD | Quetiapine did not improve psychiatric symptoms. Clozapine resulted in improvement of psychiatric symptoms, but there were persistent delusions due to partial adherence. Clozapine was discontinued due to sedation. Psychiatric improvement was observed after three weeks of paliperidone and remained stable over 5 months. |

| Carpiniello et al. (2011) [81] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Risperidone 1 mg PO daily, increased to 2 mg daily after 1 month Aripiprazole 10 mg PO daily, titrated to 15 mg daily after 2 weeks |

Not specified |

Case of delusional parasitosis. Risperidone was discontinued after 2 months due to sedation and lack of efficacy. After 4 weeks of aripiprazole, there was disappearance of delusions and hallucinations. Patient remained stable for 10 months. |

| Batalla et al. (2010) [82] | Descriptive study | 1 | Risperidone 6 mg po daily × 3 weeks, then long-acting injection 50 mg IM every 14 days | HD | Case of non-adherence to risperidone long-acting injection requiring hospital admission. PO risperidone was started and resulted in psychiatric stabilization after 2 weeks. In the third week, risperidone long-acting injection was restarted. |

| Tzeng and Chiang (2010) [83] | Descriptive study | 1 | Aripiprazole 5 mg PO daily | HD | Case of delusional parasitosis. Marked improvement in psychotic symptoms within 1 week. Self-discontinued due to lack of insight. Re-presented with psychotic symptoms 7 months later, and aripiprazole 5 mg daily was restarted. Psychotic symptoms abated in 2 months. |

| Jacob et al. (2009) [84] | Descriptive study | 1 | Clozapine titrated to 400 mg PO daily in the evening | HD | Psychiatric symptom improvement but not full remission. |

| Kaiser and Maqsood (2005) [85] | Descriptive study | 1 | Olanzapine 5 mg PO daily | HD | Case of delusional parasitosis. Patient had very good response to treatment after 3 weeks. |

| Szepietowski et al. (2004) [86] | Descriptive study | 1 | Risperidone 2 mg PO daily x 3 weeks, followed by 1 mg PO daily x 3 weeks (reason not specified) | HD | After 3 weeks, symptoms of delusional parasitosis disappeared. The patient self-discontinued risperidone after a total of 6 weeks of treatment. |

| Rueda-Vasquez (1988) [87] | Descriptive study | 1 |

Fluphenazine decampate 25 mg IM every 2 weeks Haloperidol decanoate 25 mg IM monthly in hospital, reported to be stable 1 year later on a dose of 100 mg IM monthly |

Not specified | Fluphenazine was discontinued for an unknown reason and changed to haloperidol. Haloperidol resulted in psychosis being controlled. |

| Herbert et al. (2015) [88] | Non-systematic review | 6 | N/A | HD | Limited data for delusional parasitosis in patients receiving HD. Successful use of risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, and haloperidol described in case reports. |

| Anxiety Disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Study design | Sample size | Drug regimen | Dialysis modality | Clinical outcomes and associated results |

| Schohn et al. (1982) [89] | Descriptive study |

15 HD patients 10 patients with normal kidney function |

Bromazepam 3–18 mg PO daily, divided into three doses per day. Dose titrated according to anxiolytic response and sedative effect. | HD | There was an overall decrease in anxiety signs/symptoms. In one of two cases of anxiety with depression, only one's anxiety improved. In one case of anxiety with personality disorder, bromazepam did not correct anxiety despite a high dose. |

| Studies addressing multiple mental health illnesses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Study design | Mental health illnesses | Sample size | Drug regimen | Dialysis modality | Clinical outcomes and associated results |

| Hosseini et al. (2012) [90] | Interventional study—RCT | Anxiety, Depression |

Citalopram: 22 Psychological training: 22 |

Citalopram 20 mg PO daily × 3 months | HD | No significant differences between citalopram and psychological training in the reduction of depression, anxiety, and total Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores after 3 months. |

| McGrane et al. (2022) [91] | Systematic review | Bipolar, Depression | NR | N/A | All HD patients except for 1 PD patient | Lithium can be safely used with careful monitoring. Suggested to use target lithium troughs from the 2018 Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments' bipolar guidelines. |

- Abbreviations: AE, adverse effect; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; BID, two times a day; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GI, gastrointestinal; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HD, hemodialysis; IL, interleukin; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MDD, major depressive disorder; mEq/L, milliequivalents per liter; mg, milligram; mmol/L, millimoles per liter; N/A, not applicable; ng, nanogram; NR, not reported; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PO, by mouth; PRN, as needed; QID, four times a day; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; S, at bedtime; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; TID, three times a day; ZDS, Zung Depression Scale.

| Author (year) | Patients | Intervention | Comparator | Benefit of Intervention over Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehrotra et al. (2019) [20] | 120 | Sertraline 25–200 mg PO daily | Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) | Depression scores at 12 weeks lower in sertraline group. |

| Friedli et al. (2017) [21] | 30 | Sertraline 50–100 mg PO daily | Placebo | No difference in depression scores after 6 months. |

| Zhao et al. (2016) [23] | 189 | Escitalopram 20 mg PO daily | Aerobic exercise or aerobic exercise + escitalopram | Quality of life improved in the aerobic exercise groups compared to escitalopram alone group after 18 weeks. |

| Taraz et al. (2013) [25] | 50 | Sertraline 100 mg PO daily | Placebo | Depression scores at 12 weeks lower in sertraline group. |

| Hosseini et al. (2012) [90] | 44 | Citalopram 20 mg PO daily | Psychological training | No difference in depression and anxiety scores after 3 months. |

| Blumenfield et al. (1997) [26] | 14 | Fluoxetine 20 mg PO daily | Placebo | No difference in depression scores after 8 weeks. |

| Zetin et al. (1982) [27] | 16 | Amitriptyline 50–200 mg PO daily | Placebo | No difference in depression scores after 13 weeks. |

- Abbreviation: PO, by mouth.

3 RESULTS

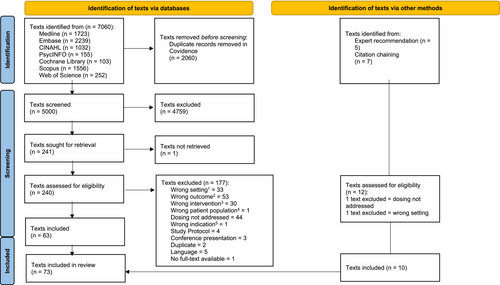

The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 2. From the peer-reviewed literature, database searches yielded 7060 potentially relevant articles prior to removing duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 240 full texts were screened. Of these, 177 articles did not meet our inclusion criteria, yielding 63 eligible articles for data extraction. Furthermore, we identified 10 additional articles based on expert recommendations and reference chaining of reviews. In total, 73 articles were included.

3.1 Depression

We found 41 articles describing the use of medications for depression in patients receiving dialysis, the majority of whom were receiving hemodialysis (HD) (Table 2). Nineteen publications, ranging from RCTs to case studies, utilized selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Sertraline at a dose of 25–200 mg daily was described in nine studies [20, 21, 25, 29, 35, 36, 41, 45, 48]. Mehrotra et al. studied sertraline versus cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in a multicenter RCT in patients receiving HD. They noted a statistically significant decrease in the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms-Clinician-Rated (QIDS-C) score at 3 months in the sertraline group, accompanied by a higher incidence of adverse effects [20]. Sertraline was also assessed against placebo in a multicentre, double-blind RCT as an initial feasibility study in HD [21]. No benefit was observed in Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS); however, the sample size in this study was small [21]. Two studies assessed sertraline while evaluating the effect of serum cytokines on depression in patients receiving HD [25, 29]. Taraz et al. compared sertraline ranging from 50 to 100 mg versus placebo [25], and Cilan et al. observed the effect of sertraline 50 mg in patients with depression [29]. Although there were inconsistent results in cytokine levels post treatment between the two studies, both authors reported overall improvement in depression scores after initiation of sertraline [25, 29]. Turk and Atalay assessed the effect of sertraline on BDI and QoL measures in patients with depression receiving HD and peritoneal dialysis (PD), respectively [35, 36]. They found sertraline 50 mg daily improved both scores after 8 weeks [36] and 12 weeks [35]. Wuerth et al. conducted a feasibility study including sertraline as a treatment option in patients receiving PD [48]. Seven patients completed 12 weeks of therapy and had an improvement in BDI scores.

Fluoxetine 20 mg daily was assessed in three studies [26, 32, 33]. One placebo-controlled trial noted a statistically significant improvement in BDI, Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), and electronic visual analog scales at the 4-week midpoint in the treatment group; however, this was not sustained to 8 weeks [26]. Fluoxetine in HD was also assessed against a cohort of patients with normal kidney function, and each group was found to have a reduction in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HAM-D-17) at the end of the 8-week study period [33]. Lee et al explored the impact of fluoxetine 20 mg daily on cytokine levels and nutritional status in 43 patients receiving HD [32]. Of all the cytokines studies, they found only a change in IL-1 beta and IL-6 at the end of the 8-week study period. No change in nutritional status and an overall decrease in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) was noted in the group. Kauffman reported the use of once weekly fluoxetine ranging in doses from 90 to 180 mg weekly in 4 patients and found this to be effective in managing symptoms of depression [38].

Citalopram 20 mg daily was evaluated in two studies [30, 90]. Hosseini et al. compared citalopram to psychological training to study its effect on depression and anxiety [90]. They did not see a difference in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) between the two groups after 3 months. Kalender et al. assessed the effect of citalopram on QoL in patients with CKD/PD/HD with depression and found improvement in two subscales of the Short Form-36 (SF-36) post treatment, also noting a significant decrease in BDI [30]. Escitalopram 20 mg daily plus aerobic exercise was evaluated against either condition alone and then together in one study of 189 patients [23]. After 18 weeks, there was an improvement in QoL, and less patients in the aerobic exercise group were in the severe depression category compared to the escitalopram groups [23].

Paroxetine combined with psychotherapy resulted in an improvement in HAM-D but not on the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale after 8 weeks [31]. Hypoglycemia potentially caused by paroxetine was described in one case report [40]. Fluvoxamine 50 mg nightly was studied in seven patients receiving HD, of which four patients had a 50% decrease in HAM-D scores [44].

Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) therapy was reported in six publications [27, 37, 49, 52-54], only two of which were trials. In one small placebo controlled trial, amitriptyline was not associated with a statistically significant improvement in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), HAM-D, Descriptive Adjective Check List, and physician depressive ratings after 13 weeks [27]. In an observational trial of patients suffering from major depression receiving HD or PD, of seven patients treated with desipramine, four patients recovered from their depressive syndrome, one patient's symptoms improved but didn't resolve, and two patients discontinued due to adverse effects [37]. There were also case reports of the use of amitriptyline [54], amoxapine [49], imipramine [53], nortriptyline [52], and maprotiline [50] although the majority include descriptions of adverse drug reactions [49, 52, 54]. Nefazodone, bupropion, and mirtazapine all demonstrated improvement in depressive symptom measures in the limited number of patients reported [39, 42, 47, 48]. Mianserin and trazodone were discontinued due to their adverse effects [37, 46].

Several other therapies have been studied in patients receiving dialysis with reports on depressive symptoms [22, 24, 28, 34, 51]. Cholecalciferol, compared to placebo, did not significantly improve BDI-II in one RCT in patients receiving HD or PD [22]; Omega-3 fatty acids demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in BDI and SF-36 versus placebo in another RCT in patients receiving HD [24]. S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) and L-carnitine demonstrated improvement in depression scores compared to baseline in two non-randomized trials in patients receiving HD [28, 34]. Methylphenidate was shown to improve depression scores in two patients receiving dialysis [51].

3.2 Bipolar disorder

We found 16 publications describing the use of medications for bipolar disorder in 17 patients receiving dialysis [60-75]. Nine case reports described lithium therapy with stable oral doses ranging from 300 to 900 mg three times a week post-HD in eight cases [61, 62, 67, 69, 70, 72-74] and 200 mg daily in one case [63]. Two cases described the use of lithium in a non-traditional fashion. Oakley et al. described lithium 0.7–1 mEq/L to be administered in the HD dialysate daily [75], and Flynn et al. described lithium 0.79–0.94 mEq/L administered via continuous ambulatory PD [71]. All cases described improvement of psychiatric symptoms with lithium therapy. Stable lithium serum levels did not exceed 1.5 mmol/L and adverse effects, when reported, included movement abnormalities [70, 75], somnolence with slurred speech [67], vomiting [75], and thirst [43]. Data from case reports described the successful use of valproic acid as part of combination therapy for bipolar disorder in patients receiving HD [60, 61, 65, 68]. Lamotrigine was also described in one case report, resulting in control of hypomanic symptoms [66]. With respect to atypical antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder, three case reports described the use of olanzapine as part of combination therapy in HD [60, 61, 68], and two cases discussed risperidone in HD [64, 68].

3.3 Schizophrenia and psychotic disorders

Eight case reports addressed pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in patients receiving dialysis [76-80, 82, 84, 87]. Aripiprazole, as monotherapy or as part of combination therapy, improved psychotic symptoms in two patients receiving HD [76, 78]. Clozapine improved symptoms in two patients with schizophrenia [80, 84]. One patient discontinued clozapine secondary to sedation and initiated paliperidone with clinical improvement noted within three weeks [80]. Risperidone and haloperidol were both reported to improve psychiatric symptoms in patients receiving HD [77, 82, 87]. One case report described occurrences of severe neutropenia with ziprasidone, which may have been dose-related [79]. Four case reports and one review addressed delusional parasitosis therapies in dialysis with the use of risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and haloperidol [81, 83, 85, 86, 88].

3.4 Anxiety disorders

We found one study that addressed anxiety disorders in patients receiving dialysis. Schohn et al. tested bromazepam in 15 patients receiving HD with anxiety [89]. A final dose range of 3–18 mg per day in divided dosing resulted in an overall improvement of anxiety symptoms. Reported adverse effects included oversedation prior to obtaining the optimal dose.

4 DISCUSSION

Seventy-three articles were included in this review: 41 focused on depression, 16 on bipolar disorder, 13 on schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, 1 on anxiety, and 2 addressing multiple mental health illnesses. The following discussion is organized by each mental health illness group.

4.1 Depression

Our review demonstrates that depression was the most extensively studied mental health illness in patients receiving dialysis. However, data describing the treatment effect for pharmacological therapy in this population are heterogeneous. Although most interventional studies report that pharmacological treatments improved depressive symptoms and depression scores, few trials are placebo controlled, and therefore, results are compared to baseline or other therapies (Table 2). The existing studies also utilized a variety of depression tools to assess outcomes, thus making it difficult to compare endpoints across studies.

The following medications have been recommended as first-line treatment in one or more general clinical guidelines for management of depression: SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), bupropion, mirtazapine, vortioxetine, trazodone, vilazodone, agomelatine, and mianserin [92-94]. In alignment with these guideline suggested first-line options, we found that SSRIs have been studied the most robustly in patients receiving dialysis (Table 3). Of the SSRIs, sertraline has been reported at doses ranging from 25 to 200 mg daily [20, 21, 25, 29, 35, 36, 41, 45, 48]; however, the evidence varies substantially from case reports to multicentre trials, with the trial outcomes varying in clinical significance. Other SSRIs that were used in controlled trials to manage depression in patients receiving dialysis include fluoxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram [23, 26, 30]. There was little evidence for the remaining first-line recommended pharmacological therapies for treatment of depression in patients receiving dialysis.

Although there is limited evidence to support the use of antidepressants in patients receiving dialysis [15], the potential use of SSRIs for management of depression in this population has been discussed widely in many reviews [55, 58, 59], with some specifically suggesting sertraline [56, 57]. This could be accomplished by titrating sertraline by 50 mg every two weeks to a maximum of 200 mg daily, with close monitoring of potential adverse effects [57]. This would be followed by a close reassessment of efficacy and discontinuation of therapy if benefit is not achieved.

With the heterogeneity of study types found in our scoping review, there was also a wide variability in the reporting of adverse effects. Mehrotra et al. found that there was a greater incidence of nervous system adverse effects in the sertraline group compared to the CBT group [20]. Taraz et al. found that sertraline carried a higher risk of nausea in patients receiving dialysis than placebo [25]. There were also reports of severe adverse effects possibly attributed to sertraline including serotonin syndrome [41], hospitalization from major bleeding, cardiac, gastrointestinal, or infectious causes [20], cardiac arrest after one dose [21], and death [25]. In a review by Kubanek et al., the use of sertraline in patients receiving dialysis was shown to have a safe impact on QTc in recommended doses, an increased bleeding and fracture risk, a reduction in the risk of intradialytic hypotension, a reduction in uremic pruritus, and a negative impact on sexual function [95]. In a large observational study, Assimon et al also noted differences in risk of sudden cardiac death with the high QT prolonging SSRIs, citalopram and escitalopram, versus fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline [96].

Our review found publications for two complementary medicine options that are listed in the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines [92]: omega-3 and SAMe [24, 34]. These therapies showed improvement in depressive symptoms in HD [24, 34, 92]; however, further research is needed before these options can be recommended for depression in patients receiving dialysis.

Non-antidepressant treatment options studied for depressive symptoms in patients receiving dialysis included cholecalciferol, methylphenidate, and lithium [22, 43, 51]. The use of cholecalciferol is not concordant with depression management guidelines [92, 93] and was not supported by one RCT in dialysis patients. Clinical guidelines suggest that methylphenidate [92] or lithium [92, 93] may be used as depression adjunctive therapies.

4.2 Bipolar disorder

Publications supporting pharmacological treatments for bipolar disorder in patients receiving dialysis are limited to case reports. The use of lithium is consistent with the joint CANMAT and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines, which recommend its use as first-line treatment for bipolar disorder and acute mania [97]. There are a variety of case reports documenting lithium use with therapeutic drug monitoring in HD [91]. Limited case report data also exist for the use of valproate, lamotrigine, olanzapine, and risperidone in mood stabilization for patients receiving HD [60, 64-66, 68]. These therapies are also supported for use in the CANMAT and ISBD guidelines [97]; however, more data are required.

4.3 Schizophrenia and related disorders

The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry Guidelines for the Pharmacological Therapy of Schizophrenia [98] and American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia [99] recommend that choice of therapy for schizophrenia be based on a discussion between the patient, caregiver, and health care team, with close assessment of therapy every 2–4 weeks following medication initiation or dose changes. Neither guideline identifies an evidence-based ranking of therapies due to a paucity of evidence informing first-line options, lack of predictability of medication efficacy, and adverse effects. A similar approach could be taken when choosing an appropriate agent in dialysis with recognition of the very limited dialysis data on aripiprazole, risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone or haloperidol in treatment-naive patients, and clozapine in treatment-resistant patients.

4.4 Anxiety disorders

Our review found limited evidence to support the use of pharmacotherapeutic options for anxiety in patients receiving dialysis. The 2014 Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders list antidepressants (SSRIs, TCAs, SNRIs), benzodiazepines, and buspirone as treatment options [100]; however, more data are required to support their use in patients receiving dialysis.

5 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The goal of this scoping review was to provide a foundational summary of pharmacological options for the management of mental health illnesses in patients receiving dialysis. This will inform the development of a pathway for mental health care for Albertans receiving dialysis [16]. The iterative person-centered process has led to a final pathway focused solely on the management of depression, anxiety, and coping. Our review included 41 articles focusing on depression and 1 article on anxiety, which ranged from case reports to RCTs. Results did not show consistent efficacy of pharmacological treatments.

With the paucity of data for antidepressant medication in this population, it is difficult to clearly recommend a large group of medications and options based on a clear benefit in dialysis. General depression guidelines may be utilized as a resource and suggest that selection of which antidepressant to use should involve shared decision making with consideration of patient preference and other clinical factors including efficacy, adverse effect potential, and cost. [92]. Additionally, in the non-dialysis population, antidepressant decision support tools have been developed to encourage shared decision making between patients and prescribers [101]. Such tools assist prescribers to narrow down antidepressant options based on a patient's comorbidities and other patient considerations. This information, coupled with pharmacokinetic information to guide medication dosing and monitoring, are essential steps in medication management in this population.

6 LIMITATIONS

While there are many strengths to this review, there are limitations that merit consideration. The methods for this review, including the inclusion/exclusion criteria, were articulated in a protocol reviewed by the research team and a steering committee. A protocol was not published or registered. We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature and included all peer-reviewed publications that reported on outcomes for treatment of mental health illnesses in patients receiving dialysis. In an effort to ensure a fulsome report, we did not limit our search strategy to the English language. However, we did not have any team members who could read articles written in Japanese, Danish, Portuguese, or Dutch; thus, these articles were excluded. During article selection, papers describing populations as “end stage kidney disease” without specifying if they were receiving dialysis were excluded to align with inclusion/exclusion criteria. It is possible that relevant articles may have been missed in these processes. Future research in this area would benefit from clear definitions of kidney failure, with or without kidney replacement therapy, and specify the dialysis modality. Our search strategy included reference chaining for all systematic reviews, as they present the highest level of evidence; therefore, we may have missed some studies. While we did not perform a formal quality appraisal of individual studies, which is not a requirement for scoping reviews, our findings present a detailed landscape of published work and highlight gaps in the literature that require future research. Given that 58% of the non-review citations presented in this scoping review are case reports, the level of evidence provided by these publications was often difficult to draw full conclusions.

7 CONCLUSION

We present current published literature on treatment of mental health illnesses in adult patients receiving dialysis. We found that SSRIs have the most data in this population. Sertraline has the most supporting data for the treatment of depression in patients receiving dialysis and may be titrated up to 200 mg daily with careful monitoring. There are limited data not only on the use of other classes of antidepressants but also on pharmacological management for anxiety in patients receiving dialysis. Data on treatment for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia are limited to case reports. More robust studies are required to establish effect sizes of pharmacological therapies prior to providing conclusive recommendations on the use of these therapies to treat mental health illnesses in patients receiving dialysis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jenny Wichart and Peter Yoeun led the Pharmacy Working Group and performed title/abstract screening, full-text screening, data extraction, full data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. They were responsible for final organization, drafting, and revision of the scoping review. Charlotte Berendonk assisted with title/abstract screening, full-text screening, data extraction, drafting of the manuscript, and review of the manuscript. She was responsible for data and project management. Megan Kennedy was responsible for the systematic literature search and assisted with review of the manuscript. Kara Schick-Makaroff assisted with title/abstract screening, full-text screening, data extraction, drafting of the manuscript, and review of the manuscript. She was the lead investigator of the pathway development project in which this scoping review is embedded. All other authors assisted with title/abstract screening, full-text screening, data extraction, drafting of the manuscript, and review of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the Kidney Foundation of Canada for funding the pathway development project: https://kidney.ca/Research/Supported-Research/ABS/Tailoring-a-Pathway-for-Mental-Health-Care-for-Alb, in which this scoping review is embedded (Funding Reference Number 856688-21AHKRG). We are very grateful to Eva Kuang and Yoon Hwang for their support of the literature screening and data extraction process. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the support of Heidi Wyse in the translation and literature assessment and the Alberta Health Services librarian team for their assistance with article retrieval.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Kara Schick-Makaroff (KSM) and Charlotte Berendonk (CB) acknowledge the funding received for the project “Tailoring a pathway for mental health care for Albertans on dialysis.” The funding was provided by the Kidney Foundation of Canada (Funding Reference Number 856688-21AHKRG). KSM is the principal investigator, CB is the research associate coordinating the project. None of the other authors have any financial or non-financial relationships and activities or conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors were solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of this manuscript, and its final contents.