Parenting beliefs and practices as precursors to academic outcomes in Chinese children

Abstract

Due to the rapid sociocultural changes in China, Chinese parents' childrearing beliefs and practices have undergone dramatic transformations. Against this context, this study examined whether Chinese parents' endorsement of progressive and traditional childrearing beliefs would predict children's academic achievement, as well as whether parenting practices would mediate this association. This study utilized a longitudinal design and followed 206 Chinese families for 2 years from the end of preschool to Grade 2. Parents showed greater endorsement of progressive than traditional childrearing beliefs, as well as higher use of authoritative than authoritarian parenting practices. Parents' childrearing beliefs in preschool predicted children's math achievement in Grade 2 via authoritative parenting. However, parenting beliefs were unrelated to authoritarian parenting, and authoritarian parenting did not predict any of the child academic outcomes in Grade 2. The findings suggest Chinese parents' orientations toward progressive parenting beliefs and authoritative parenting practices. They also highlight the utility of parenting beliefs in explaining disparities in early academic achievement. The nonsignificant findings pertinent to authoritarian parenting call for re-examination of the cultural meaning and effects of authoritarian parenting in Chinese society.

INTRODUCTION

Although there has been an ebb and flow in the interest in studying parenting beliefs over the last four decades, parenting beliefs constitute an important domain of parenting and affect virtually every aspect of children's development (Sigel & McGillicuddy-De Lisi, 2002). Parenting beliefs are parents' mental constructions of experience, and they are often condensed and organized into schemata or concepts that are conceived to be true and that can guide parenting practices (Hirsjärvi & Perälä-Littunen, 2001). In fast-developing societies, such as China, where economic, political, social, and/or cultural changes occur in an extremely condensed manner with respect to both time and space, dramatic transformation of parenting often occurs, and disparate parenting beliefs and practices can coexist under such a condition (Lan, 2014). As a result, parenting beliefs and practices may show considerable within-cultural variations in societies with rapid sociocultural changes, generating significant impact on children's development and learning. Situated in the Chinese context, the current study aimed to uncover how variations in parenting beliefs were linked to children's academic competence via parenting practices. To test the longitudinal succession from parenting beliefs to practices to child development, data need to be collected for three temporally separate waves (Bornstein et al., 2018). This study utilized such a longitudinal design to evaluate how early parenting beliefs would predict parenting practices and eventually children's later academic outcomes.

Parenting beliefs and academic competence

Parenting belief is an umbrella term that encompasses parents' ideas, knowledge, values, goals, and attitudes regarding childrearing (Rubin & Chung, 2006). Many previous studies centered on specific aspects of parenting beliefs. For instance, some studies focused on parents' beliefs about children's learning in certain subject areas, such as mathematics and reading, and such beliefs were shown to be strong predictors of children's achievement in these areas (e.g., Sonnenschein et al., 2012; Stephenson et al., 2008). Other studies considered parenting beliefs more broadly. In the current study, we focused on parenting beliefs about adult authority regarding childrearing and corresponding educational values. Schaefer (1987, 1991) proposed the parental modernity construct to capture “individual differences in parents' conceptions of children's inherent characteristics and the related beliefs about how to best approach parenting that stem from those conceptions” (Mulvaney & Morrissey, 2012, p. 1106). Parents upholding traditional beliefs tend to view children as born evil, value directive parenting, and emphasize adherence to authority. In contrast, parents endorsing progressive beliefs cherish children's curiosity and autonomy, and they believe in the value of self-directed and informal learning (Schaeffer & Edgerton, 1985).

Research conducted in the United States demonstrated positive associations between parental modernity and cognitive/academic competence in children (e.g., Okagaki & Sternberg, 1993; Shears & Robinson, 2005). For instance, Okagaki and Sternberg (1993) found that stronger parenting beliefs in the importance of conformity were linked to worse language, reading, math, and overall academic skills measured via individual assessments, as well as worse teacher-rated academic performance and classroom behavior. There is also evidence supporting the long-term effects of parenting beliefs on children's later cognitive/academic development (Burchinal et al., 2002; Im-Bolter et al., 2013; Keels, 2009; Liew et al., 2018; Mulvaney & Morrissey, 2012). For instance, progressive (traditional) parenting beliefs at 24 months of age for children were found to positively (negatively) predict children's academic achievement in Grade 5. Im-Bolter et al. (2013) revealed that stronger traditional parenting beliefs at the age of 1 month for children predicted poorer language development at 36 months as well as worse academic competence in kindergarten and Grade 1. These findings underscore the utility of parenting beliefs in explaining achievement disparities.

Parenting beliefs, parenting practices, and child development

Parenting beliefs serve as a roadmap that guides parenting practices, although parents' cognitions do not always map onto their practices directly (Bornstein et al., 2018). Many studies have shown the connections between various aspects of parenting beliefs and practices (see reviews by Ng & Wei, 2020; Okagaki & Bingham, 2005), as well as between parenting practices and child academic outcomes (see meta-analysis by Pinquart, 2016). In comparison, few studies have explored the direct link between parenting beliefs and child academic achievement, as parenting beliefs are often conceptualized as a distal factor that influences child development. In addition, empirical efforts to test the “parenting cognitions → parenting practices → child adjustment” standard model are rather limited, and this longitudinal association is often simply assumed in parenting research and interventions (Bornstein et al., 2018). However, several prior studies did provide support for this consecutive three-term model. For instance, focused on African-American single-mother-headed households, Brody et al. (1999) found that mothers' value of developmental goals was related to competence-promoting parenting practices, which was further related to children's self-regulation and their academic and psychosocial outcomes. Through an 8-year longitudinal study, Bornstein et al. (2018) showed that aspects of parenting cognition when children were 20 months old predicted supportive parenting at 4 years of age, which further predicted fewer externalizing behavior problems in children at 10 years old.

Two previous studies on American families living in poverty were particularly relevant to the current study, as they included parental modernity as a variable of interest (Keels, 2009; Liew et al., 2018). Specifically, Keels (2009) reported that parenting cognitions (a latent variable composed of knowledge of infant development, parental modernity, and beliefs about early language and literacy stimulation) were positively related to supportive parenting, which was further related to children's cognitive competence at 24 months old. Liew et al. (2018) found that stronger endorsement of progressive parenting beliefs at the age of 24 months for children predicted higher maternal supportiveness and lower maternal intrusiveness at 36 months, while the above associations were opposite for traditional parenting beliefs. Furthermore, maternal supportiveness and intrusiveness predicted children's academic achievement and certain aspects of psychosocial functioning in Grade 5 either directly or indirectly via self-regulation.

Research on parenting beliefs of Chinese parents

Chinese parents' childrearing beliefs have been a prominent topic of investigation, and many studies have linked parenting beliefs to practices (see reviews by Luo et al., 2013; Ng & Wei, 2020). A few studies tested the “parenting cognitions → parenting practices → child adjustment” model in Chinese families (e.g., Leung & Shek, 2016; Ren & Edwards, 2015; Zhong et al., 2020). However, the existing studies typically used a cross-sectional design, leaving the direction of effects unclear, and concurrent measures would also likely inflate relations between constructs (Bornstein et al., 2018). Rigorously testing the above cascade model using a longitudinal design and controlling for child baseline development is crucial in the Chinese context, as the findings will not only reveal whether parenting beliefs would affect parenting practices and child academic achievement amid rapid social changes but also provide insights for effective parenting interventions that can promote child development.

In addition, few studies explored the parental modernity construct among Chinese parents (Chang et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2021). The continuum of traditional-progressive parenting beliefs as captured in the parental modernity construct reflects the cultural orientations of European-American middle-class families (Keels, 2009). With the influx of Western parenting ideologies, some Chinese parents are moving away from traditional Chinese parenting that values obedience and increasingly endorse creativity and independence in children (Ren, 2015). Chang et al. (2011) and Hu et al. (2021) both found that Chinese parents endorsed progressive beliefs more than traditional beliefs. In a cross-cultural study comparing nine countries (i.e., China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States), Chinese parents reported stronger progressive beliefs and weaker traditional beliefs than the grand mean (Bornstein et al., 2011). However, there exist notable variations in Chinese parents' endorsement of these beliefs, suggesting the need to pay attention to within-cultural variations in Chinese parents' beliefs (Chang et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2021).

Educational attainment remains a key vehicle for social mobility in China, and competition in education has become increasingly fierce despite the expansion of higher education and constant educational reforms for quality (Zhu & Chang, 2019). Against this background, Chinese parents continue to have high academic expectations and be heavily involved in education, and many still emphasize conformity and tight parental control, although there is also a trend of adopting progressive parenting beliefs and practices to cultivate individualistic traits in children (Luo et al., 2013; Zhu & Chang, 2019). In this rapidly changing Chinese context where competing demands for child development coexist, do parenting beliefs manifest in actual practices and produce impacts on children's academic competence? The answer to this overlooked question will provide a deeper understanding of Chinese parenting.

The present study

The purpose of the study was to examine how Chinese parents' endorsement of traditional and progressive beliefs would relate to parenting practices and child academic outcomes. We hypothesized that parenting practices would mediate the link between parenting beliefs and child outcomes. To establish temporal precedence for the mediation model, parenting beliefs were assessed in preschool, while parenting practices and child academic outcomes were measured in Grades 1 and 2, respectively. We hypothesized that when parents endorsed progressive beliefs more strongly, they would show higher levels of authoritative parenting and lower levels of authoritarian parenting, and subsequently, children would show better academic competence. Opposite associations were hypothesized for traditional parenting beliefs.

METHOD

Participants and procedures

The present study included 206 parent–child dyads from Zhongshan City of Guangdong, a province located in southern China. In the parent sample, 62.6% were mothers and 37.4% were fathers. The child sample consisted of 50% boys and 50% girls. We followed them for 2 years. In China, preschools are typically 3-year programs serving children aged 3–6 years. At T1 (May 2016), parents reported their childrearing beliefs when their children were in the last semester of preschool. One year later (May 2017), parents reported their parenting practices when children were in Grade 1 (T2). At T3 (May 2018), child academic outcomes (i.e., math achievement, receptive vocabulary, and Chinese reading) were measured using individual assessments when children were in Grade 2. At T1, the same assessments were utilized to measure children's baseline receptive vocabulary and Chinese reading. Children's baseline math skills were measured using a different one-on-one assessment at T1. Children were on average 6.31 years old (SD = 0.85) at T1. In the sampled families, 62.6% of the mothers and 49.5% of the fathers had an annual income below 50,000 RMB ($7246). Over half of the parents (58.2% mothers and 57.8% fathers) had an educational level below a college degree (see Appendix A).

Data collection was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Macau. We randomly selected 20 preschools from a complete list provided by the local department of education in Zhongshan. Next, we randomly selected one classroom of the target age group and then randomly selected 8–12 families from the chosen classroom. Once graduating from preschools, the sample children went on to attend 45 different elementary schools, with each school containing 1–13 children from our sample. Parents provided consent for both their own participation and that of their children in this study. An envelope of questionnaires was sent home for primary caregivers to complete individually, both at T1 and T2. All questions were printed in Chinese. Trained graduate research assistants implemented standardized tests to assess children's academic skills at T1 and T3 in quiet rooms prepared by the schools.

Measures

Parenting beliefs

Parents reported their parenting beliefs using the Parental Modernity Scale (Schaeffer & Edgerton, 1985). It consists of two subscales: progressive beliefs (8 items; e.g., “Children can express their disagreement with their parents”) and traditional beliefs (22 items; e.g., “Children should not challenge parents' authority”). Parents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This scale has been used among Chinese samples (Chang et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2021). In the present study, satisfactory to high reliability was found for the progressive beliefs subscale (α = 0.73) and the traditional beliefs subscale (α = 0.94). Confirmatory factor analysis showed that a two-factor model of progressive beliefs and traditional beliefs had an acceptable fit (χ 2/df = 2.57, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.07).

Parenting practices

Parenting practices were measured with the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Robinson et al., 1995). The PSDQ has been widely used among Chinese parents (e.g., Liu et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2020). The authoritative parenting subscale has 27 items and captures parents' warmth and involvement, use of reasoning and induction, and autonomy granting. The authoritarian parenting subscale contains 20 items and measures parents' use of punitive disciplinary strategies, nonreasoning, and directiveness. The permissive parenting subscale was not used due to its poor psychometric properties among Chinese families (Ren & Edwards, 2015). Parents rated how often they showed each described behavior on a 5-point scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (always). In this study, both the authoritative parenting (α = 0.93) and the authoritarian parenting subscale (α = 0.80) had satisfactory reliability.

Math achievement

At T1, children's math abilities were assessed by the Test of Children Mathematic Achievement (TCMA; Xie, 2014). The TCMA is a one-on-one assessment developed for use among Chinese children. It contains 120 items that cover various formal and informal math skills, such as solving math equations and story problems. Although the TCMA was developed for children aged 3–9 years, a ceiling effect tends to occur for Grade 2 students in Chinese samples. Therefore, we switched to a different test at T3, namely the Math Achievement Test (MAT; Dong & Lin, 2011). The MAT contains 28 items that assess math skills in calculation, graphics, and statistics. It is a paper–pencil test, and children took the test at school in a quiet room under the guidance of trained graduate research assistants. In this study, the measures used at T1 (α = 0.91) and T3 (α = 0.85) both showed satisfactory reliability.

Receptive vocabulary

We measured children's receptive vocabulary with the Chinese Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-R (C-PPVT-R; Lu & Liu, 2005) at T1 and T3. The C-PPVT-R includes 125 items. For each item, the tester reads out loud a word to the child, and the child is requested to identify the correct picture that corresponds to the word. Cronbach's alpha for the assessment was 0.96 at T1 and 0.88 at T3.

Chinese reading

Children's Chinese reading skills were assessed using the Chinese Character Recognition Task (Shu et al., 2008). In this task, children are presented with a list of 150 Chinese characters, and they need to read them aloud one by one. The test is terminated when children respond incorrectly to 15 consecutive items. This test showed high reliability both at T1 (α = 0.96) and T3 (α = 0.97).

Analytic strategies

Data were analyzed in Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). We constructed a structural equation modeling (SEM) model that included parenting beliefs as independent variables, parenting practices as mediators, and children's T3 academic outcomes as dependent variables. We regressed covariates (i.e., children's gender, age, and baseline academic outcomes) on the dependent variables. When regressed on the mediators, covariates did not have significant effects (−0.07 ≤ β ≤ 0.13; ps > 0.05) and thus were eventually removed for model simplicity.

Maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) was employed for model estimation. We had complete data for parenting variables. For child outcomes, 42 children had missing data at T3. Little's MCAR test showed that the data could be considered as missing completely at random (χ 2 = 63.04, df = 48, p = 0.071). The missing values were handled with full-information maximum-likelihood estimation (FIML) in Mplus. To check whether missing data would harm the statistical power, a post-hoc power analysis was done using a Monte Carlo simulation approach in Mplus. As small-to-medium effects were found in our final SEM model (between 0.17 and 0.21), the effect size was set to 0.20 in the post hoc power analysis. Given our sample size (N = 206) and the pattern of missing data (20% missing at T3), the power to detect a small-to-medium effect (β = 0.20) was between 0.86 and 0.89 for all effects except for one (power = 0.70), suggesting an overall sufficiency of power. To examine indirect effects, we used the “Model Indirect” function in Mplus. Standardized coefficients were reported with 95% confidence interval (CI).

RESULTS

Descriptives and correlations

As shown in Table 1, parents reported greater endorsement of progressive beliefs as well as more frequent use of authoritative parenting compared to traditional beliefs (t(205) = 16.76, p < 0.001) and authoritarian parenting (t(205) = 30.35, p < 0.001), respectively. Unexpectedly, progressive beliefs were not significantly correlated with traditional beliefs, and authoritative parenting did not correlate with authoritarian parenting, either. Parents' progressive beliefs were positively correlated with authoritative parenting and children's receptive vocabulary. Parents' traditional beliefs were negatively related to authoritative parenting and all child academic outcomes. Authoritative parenting had positive relations with children's math achievement and Chinese reading but was not significantly correlated with receptive vocabulary. Authoritarian parenting did not have significant associations with any of the academic outcomes.

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Progressive Beliefs | 3.96 | 0.49 | 0.17 | −0.37 | — | |||||

| 2. T1 Traditional Beliefs | 2.93 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.87 | −0.05 | — | ||||

| 3. T2 Authoritative Parenting | 3.61 | 0.58 | −0.36 | 0.54 | 0.24*** | −0.30*** | — | |||

| 4. T2 Authoritarian Parenting | 2.15 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 2.20 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.03 | — | ||

| 5. T3 Math Achievement | 16.93 | 4.66 | 0.09 | −0.77 | 0.11 | −0.25** | 0.26*** | 0.10 | — | |

| 6. T3 Receptive Vocabulary | 96.53 | 11.45 | −0.46 | −0.56 | 0.16* | −0.25** | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.46*** | — |

| 7. T3 Chinese Reading | 88.77 | 21.05 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.14 | −0.19* | 0.24** | 0.08 | 0.56*** | 0.52*** |

- *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Model estimation and direct effects

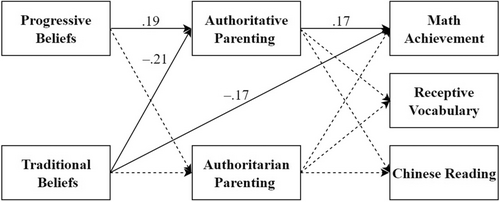

To examine the hypothesized mediation effects of parenting practices on the link between parenting beliefs and child academic outcomes, we started with a partial mediation model. The direct effects of parenting beliefs on children's academic outcomes were estimated, in addition to the associations between parenting beliefs and parenting practices, and between parenting practices and child academic outcomes. Only parents' traditional childrearing beliefs were found to negatively predict children's math achievement. All other direct effects of parenting beliefs on child outcomes were nonsignificant (−0.06 ≤ β ≤ 0.07; ps > 0.05) and thus were removed from the final model. The final model (see Figure 1) had a satisfactory model fit, χ 2 (18) = 41.89, p = 0.001, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.08.

As shown in Table 2, parents' greater endorsement of progressive beliefs predicted higher use of authoritative parenting (β = 0.19, p = 0.003, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.31]), whereas parents' greater endorsement of traditional beliefs predicted lower use of authoritative parenting (β = −0.21, p = 0.002, 95% CI = [−0.34, −0.07]). However, neither progressive (β = 0.02, p = 0.774, 95% CI = [−0.12, 0.16]) nor traditional beliefs (β = 0.11, p = 0.167, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.26]) significantly predicted authoritarian parenting. Regarding the relationship between parenting practices and child academic outcomes, authoritative parenting positively predicted child math achievement (β = 0.17, p = 0.015, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.31]). However, parenting practices did not significantly predict receptive vocabulary or Chinese reading skills (−0.02 ≤ β ≤ 0.07, ps > 0.05).

| Mediator | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritative parenting | Authoritarian parenting | Math achievement | Receptive vocabulary | Chinese Reading | |

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Direct effect: | |||||

| Independent variable → Mediator/Outcome | |||||

| Progressive Beliefs | 0.19** (0.06) | 0.02 (0.07) | — | — | — |

| Traditional Beliefs | −0.21** (0.07) | 0.11 (0.08) | −0.17* (0.07) | — | — |

| Mediator → Outcome | |||||

| Authoritative Parenting | — | — | 0.17* (0.07) | −0.02 (0.07) | 0.07 (0.06) |

| Authoritarian Parenting | — | — | 0.11 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.05) |

| Indirect effect: | |||||

| Progressive Beliefs → Authoritative Parenting → Outcome | 0.03+ (0.02) | — | — | ||

| Traditional Beliefs → Authoritative Parenting → Outcome | −0.04* (0.02) | — | — | ||

| R 2 | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.33 (0.06) | 0.57 (0.06) |

- Note: Children's gender, age, and baseline academic achievement (i.e., T1 math achievement, receptive vocabulary, and Chinese reading) were controlled. In the original SEM model, for each outcome, the corresponding baseline variable was controlled. For example, in predicting T3 math achievement, only T1 math achievement was included as a covariate in addition to child gender and age. However, additional paths were added based on model modification indices to reach acceptable model fit. Specifically, in the final model, T1 Chinese reading was also regressed on T3 receptive vocabulary, while T1 receptive vocabulary was regressed on T3 Chinese reading as well.

- *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, +p < 0.10.

Indirect effects

Tests of indirect effects showed that authoritative parenting mediated the associations between parenting beliefs and children's math achievement. Specifically, parents' traditional beliefs were negatively related to children's math achievement via authoritative parenting (β = −0.04, p = 0.042, 95% CI = [−0.07, 0.00]). The indirect effect of progressive beliefs on child math achievement via authoritative parenting also approached significance (β = 0.03, p = 0.052, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.07]). After accounting for parenting practices, greater endorsement of traditional beliefs continued to predict lower math achievement (β = −0.17, p = 0.012, 95% CI = [−0.30, −0.04]).

DISCUSSION

Whether and how early parenting beliefs are related to later academic competence in Chinese children has been overlooked. To address this issue, we conducted a longitudinal study that followed Chinese families for 2 years. Our findings suggest that parents showed greater endorsement of progressive parenting beliefs and authoritative practices relative to traditional beliefs and authoritarian practices. We also found that Chinese parents' childrearing beliefs in preschool predicted children's math achievement in Grade 2. Parents' authoritative but not authoritarian parenting practices mediated the above association. The findings highlight the important role of parenting beliefs in children's academic skill development through shaping parenting practices. Some nonsignificant findings also reveal unique characteristics of Chinese parenting and underscore the need for a closer view of Chinese childrearing.

Chinese parents' childrearing beliefs

Consistent with previous studies (Chang et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2021), Chinese parents in our sample endorsed progressive more than traditional beliefs. Drawing upon the framework of cultural revolution (Boyd & Richerson, 2005), Chang et al. (2011) argued that the unprecedented social change in China propelled parents to depart from traditional collectivistic cultural orientations and shift toward individualistic cultural values in childrearing because innovation-oriented individual learning would be more adaptive than tradition-oriented social learning in times of rapid environmental changes. Qualitative studies have also revealed Chinese parents' value of creativity, independence, and psychological quality in raising children (e.g., Fong, 2007; Ren, 2015; Way et al., 2013). In line with these recent studies, our findings further challenge the traditionalist view that Chinese parents value children's obedience and emphasize directed parenting.

Interestingly, this study shows that greater endorsement of progressive childrearing beliefs does not necessarily indicate less emphasis on traditional beliefs in the Chinese context. Unlike in Western contexts where progressive beliefs are often negatively correlated with traditional beliefs (e.g., Burchinal et al., 2002; Liew et al., 2018), we observed a nonsignificant correlation between these two sets of beliefs. Similarly, in Hu et al.'s (2021) study of 532 Chinese parents with preschool-aged children, the correlation between parents' traditional and progressive beliefs was very weak albeit statistically significant (r = −0.094). Through qualitative interviews, Fong (2007) explained that some Chinese parents upheld mutually contradictory values in childrearing, such as they wished their children to be obedient yet independent. She argued that this “uneasy coexistence of multiple contradictory values” (p. 116) was the product of “an uneasy mixture of Confucianism, socialism, and capitalism” (p. 110) driven by the rapid social, political, economic, and demographic changes in Chinese society. This aligns with Chang's (2010) theory of compressed modernity that diverse components of multiple civilizations often coexist and influence each other when a society experiences sociocultural changes in an extremely condensed manner, which likely leads to transformations in parenting discourses and childrearing repertoires (Lan, 2014).

Role of parenting beliefs in child academic outcomes via authoritative parenting

Congruent with previous findings (Keels, 2009; Liew et al., 2018), we found that progressive beliefs positively, while traditional beliefs negatively, predicted the use of authoritative parenting. When parents uphold progressive beliefs as opposed to traditional ones, they may be more inclined to cultivate children's curiosity and independence as well as promote self-directed learning through practicing authoritative parenting. Parents who adopt an authoritative parenting style tend to exhibit warmth and affection, use reasoning and induction instead of punitive disciplinary measures, encourage autonomy, and foster the expression of individual ideas. The alignment between parenting beliefs and practices reflects the idea that caregivers' cognitions do help shape their practices to some extent (Bornstein et al., 2018).

Higher levels of authoritative parenting predicted better math performance in children. This finding was consistent with many prior studies on Chinese families (e.g., Chen, 2015; Chen et al., 1997; Wang, 2014). Authoritative parenting can promote security, confidence, and an overall positive orientation in children, which may promote high academic motivation and achievement (Chen et al., 1997). In addition, parents who use an authoritative parenting style tend to be more responsive to their children's needs, and this style of parenting is moderately associated with parental scaffolding behaviors during math lessons (Mattanah et al., 2005). Authoritative parenting was also found to support children's math self-efficiency while reducing their math anxiety (Macmull & Ashkenazi, 2019), both crucial for children's math achievement (Du et al., 2021).

However, authoritative parenting only predicted math achievement, but not receptive vocabulary or Chinese reading. One possible reason is that the same assessments were applied to measure receptive vocabulary and Chinese reading at T1 and T3, and therefore, much variance in T3 competence had been explained by baseline performance, leaving little variance to be explained by other predictors. In addition, the effects of authoritative parenting on language and reading outcomes were mixed in the literature. Some studies showed weak but significantly positive relations between authoritative parenting and receptive language (Ren et al., 2019, 2020; Roopnarine et al., 2006) or reading skills (Hill, 2001; Lam & Chung, 2023), while others reported nonsignificant results (e.g., receptive language in Bingham et al., 2017; reading in Kiuru et al., 2012 and Ren et al., 2019, 2020). Authoritative parenting may allow for more open and extensive verbal exchanges between parents and children, promoting children's receptive language and reading skills. However, considering that the associations between authoritative parenting and language/reading tend to be small in magnitude or nonsignificant across many previous studies, the use of authoritative parenting in itself may not be adequate to sufficiently boost children's language/reading skills. Parenting practices pertinent to language and reading may be more crucial, such as shared reading and explicit teaching of Chinese characters.

The lack of mediation effects of authoritarian parenting

Authoritarian parenting was not predicted by parenting beliefs, contradicting Liew et al.'s (2018) finding that higher traditional beliefs led to increased maternal intrusiveness. Although Chinese parents tend to report relatively low levels of authoritarian parenting nowadays (Lu & Chang, 2013; Ren & Edwards, 2015), Liu et al. (2018) contended that Chinese parents might still engage in authoritarian parenting to some extent, especially in response to children's academic and behavioral difficulties. Parents' use of authoritarian parenting practices might not be driven by their internal beliefs in the value and effectiveness of such parenting strategies but by external socio-structural challenges in China today (e.g., decreasing social mobility and increasing academic pressure) and the habituation of adopting traditional parenting practices that they once experienced as a child. This may explain the lack of association between parenting beliefs and authoritarian parenting. In addition, changes in Chinese parents' ideals may precede their actual practices because it takes time for them to learn about, acquire, and solidify practices that correspond with newly cherished beliefs and values (Ren, 2015). The discrepancy between parenting beliefs and practices in Chinese families may also be a tentative explanation for the lack of associations between parenting beliefs and authoritarian parenting. According to Ren's (2015) finding that some Chinese parents engaged in authoritarian parenting while showing uncertainty and insecurity in such practices, the discrepancy between parenting beliefs and practices might be particularly evident for authoritarian parenting.

Contrary to the hypothesis, authoritarian parenting did not predict any of the child academic outcomes. In the Western literature, authoritarian parenting is often associated with negative connotations, as it has been widely linked to negative child outcomes (Pinquart, 2016). However, in the Chinese context, some aspects of parental control and strictness inherited in the concept of authoritarian parenting imply parental concern, caring, or involvement (Chao, 1994). Several studies have documented that authoritarian parenting can have positive effects on a child's cognitive and academic abilities (e.g., Chen, 2015; Leung et al., 1998; Li & Xie, 2017). Yet, many studies supported a negative role of authoritarian parenting in child academic-related outcomes, which corroborated findings in the West (e.g., Chen et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019). Ren et al. (2020) also reported a lack of correlation between authoritarian parenting and Chinese preschoolers' early academic skills. Thus, there are conflicting results regarding the impact of authoritarian parenting. In addition, the connection between authoritarian parenting and child academic achievement tends to be weaker and less consistent compared to that between authoritative parenting and child outcomes (Pinquart, 2016). In conclusion, with the widespread transformation in Chinese family structure and normalized childrearing practices, the cultural meaning and effects of authoritarian parenting, as well as the typology of parenting, in contemporary Chinese society may require renewed attention.

Limitations and conclusions

Several limitations need to be noted. First, our study sample came from Guangdong, a province with advanced economic development in China. Our results may not generalize to other parts of China. Research with more representative samples is needed to validate our findings. Second, we only assessed academic outcomes in children. Nonacademic outcomes (e.g., motivation for learning, attitudes toward school, and social–emotional competence) may also be included to examine whether they may serve as underlying pathways through which parenting beliefs and practices relate to children's academic outcomes. Finally, although a variety of child and family characteristics were controlled in our analysis, we did not have information about other relevant variables that could be controlled for, such as the parents' relationship status.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for family education and family research in China. In 2022, the Chinese government enacted the Family Education Promotion Law, spawning an unprecedented need for evidenced-based programs to improve parenting quality and child development in Chinese families. This study showed that parenting beliefs did matter for parents' use of authoritative parenting practices and children's math achievement. Although parenting beliefs tend to be resistant to change as they are often implicit ideas about childrearing, adjusting parenting beliefs may be critical to promoting and sustaining changes in parenting practices and child development (Rubin & Chung, 2006). Our findings suggest that family education programs may help parents reflect on their childrearing beliefs and shift them toward more progressive and less traditional orientations. In addition, our finding that authoritarian parenting was unrelated to parenting beliefs and child academic outcomes suggests that the cultural meaning of authoritarian parenting requires a critical revisit. Family researchers need to update our view on how authoritarian parenting is perceived and practiced in contemporary Chinese society. Third, we found that traditional beliefs continued to predict math achievement after accounting for the mediation effect of authoritative parenting, indicating the existence of other underlying mechanisms. Parenting practices that are specifically related to learning, such as school-related parental involvement, may be important mechanisms to consider in future research. In conclusion, the current study highlights the role of parenting beliefs and practices in Chinese children's academic competence, particularly math achievement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the project “The effects of preschool program quality on children's mid- to long-term learning and development outcomes: A follow-up three-year longitudinal study” funded by the University of Macau Multi-Year Research Grant (MYRG2Ol8-00024-FED; awarded for 2018-2021 school year).

APPENDIX A: A DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION OF THE PARTICIPANTS

| Variables | M (SD)% |

|---|---|

| Child characteristics | |

| Age at T1 (year) | 6.31 (0.85) |

| Gender | |

| Boys | 50% |

| Girls | 50% |

| Family characteristics | |

| Parent's gender | |

| Female | 62.6% |

| Male | 34.5% |

| Maternal annual income | |

| < 5000 RMB ($725) | 20.9% |

| 5000–20,000 RMB ($2900) | 15.5% |

| 20,000–50,000 RMB ($7246) | 26.2% |

| 50,000–80,000 RMB ($11,600) | 15.5% |

| 80,000–100,000 RMB ($14,500) | 10.2% |

| > 100,000 RMB | 7.8% |

| Maternal education level | |

| Elementary school | 2.4% |

| Middle school or below | 29.6% |

| High school or vocational high school degree | 26.2% |

| Vocational college degree | 24.8% |

| Bachelor's degree | 13.6% |

| Master's degree or above | 2.9% |

| Paternal annual income | |

| < 5000 RMB ($725) | 11.1% |

| 5000–20,000 RMB ($2900) | 15.1% |

| 20,000–50,000 RMB ($7246) | 23.3% |

| 50,000–80,000 RMB ($11,600) | 15.0% |

| 80,000–100,000 RMB ($14,500) | 13.1% |

| > 100,000 RMB | 18.9% |

| Paternal education level | |

| Elementary school | 1.0% |

| Middle school or below | 26.7% |

| High school or vocational high school degree | 30.1% |

| Vocational college degree | 18.0% |

| Bachelor's degree | 22.3% |

| Master's degree or above | 1.5% |