Honouring the Past, Embracing the Future

The United Church of Canada at 100

Abstract

The United Church of Canada, founded in 1925, represents an ambitious experiment in church union that blends Methodist, Presbyterian, and Congregationalist traditions. Over the past century, the church has played a pivotal role in shaping Canadian society by advocating for social justice, Indigenous reconciliation, interreligious dialogue, 2SLGBTQIA+ rights, and ecumenism. Its commitment to progressive values has resulted in both cultural impact and institutional challenges, particularly with the rise of secularism. The church has continually evolved, addressing theological and social transformations from its early mission-driven church union to its engagement with contemporary issues. This article examines whether the United Church is a victim of its success – mainstreaming its values to the point of institutional decline – or if its legacy of adaptation will enable it to thrive in the future, reimagining faith in the 21st century.

The United Church of Canada was founded in 1925 as a bold experiment in church union, uniting Methodist, Presbyterian, and Congregationalist traditions to establish a united national Protestant church. Over the past century, the United Church has played a pivotal role in shaping Canada's religious and social landscape and global ecumenism, advocating for progressive initiatives such as racial and gender justice, Indigenous reconciliation, 2SLGBTQIA+ rights, and interreligious dialogue. However, the church faces a paradox as it enters its second century. While many of its core values have become widely accepted in Canadian society, the institution itself is experiencing declining membership and questions about its enduring role in an increasingly secular society.

This article explores the evolution of the United Church, highlighting its defining moments, challenges, and unwavering commitments. It first examines the church's historical formation, tracing the ecumenical movement that led to its establishment and the theological and social motivations that shaped its early years. Next, it looks at how the church's vision – often balancing the dual callings of spiritual renewal and social transformation – has evolved over time, particularly in response to historical crises such as the Great Depression. It then traces the church's role during and after the Second World War, exploring the changing landscape as the Canadian government expanded its role in public services, which led to the church's diminishing influence.

This article will then analyze the major paradigm shifts in the United Church's mission approach during the latter half of the 20th century, particularly in light of the World Mission report (1966), which marked a radical departure from ecclesiastical colonialism. The report embraced missio Dei, viewing mission as God's work rather than merely church expansion. It emphasized partnership over hierarchy, affirmed religious pluralism, and prioritized social justice, redefining mission as a collaborative and egalitarian effort to address human concerns. The final sections reflect on the church's vision to become an intercultural church and the contemporary challenges it faces, including the rise of secularism and declining religious affiliation in Canada. This article examines the United Church's past, present, and future to provide insight into how religious institutions can navigate social change while remaining true to their founding vision.1

Uniting Church

Before European settlers arrived on Turtle Island, now known as North America, Indigenous peoples had lived on the land for thousands of years. In what later became Canada, many Indigenous communities welcomed those who brought the Christian gospel, viewing it as a way to strengthen their relationship with the Creator and promote kinship. The Wesleyan Methodist Board of Foreign Missions established churches among the Mohawk (Haudenosaunee) nations of Ontario and Mississauga in the early 19th century. By the late 1830s, both Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) and English Methodist clergy were ministering in northwest Ontario and the Prairie provinces. Methodist missions expanded to Vancouver Island in 1859, while Canadian Presbyterians began work in the Prince Albert region in 1866. In 1899, collaboration between Presbyterian and Methodist mission boards helped lay the groundwork for the eventual church union movement.2

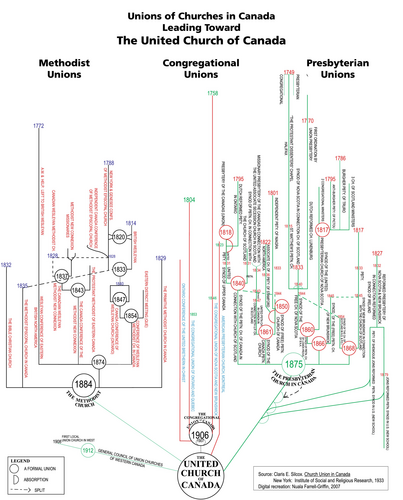

The idea of church union in Canada had been a “long cherished hope.”3 The movement toward church union was not a sudden development but rather a gradual process driven by theological, missiological, practical, and social motivations for over 50 years before the formation of The United Church of Canada in 1925. As early as 1874, the Diocesan Synod of Québec of the Church of England initiated conversations about the possibility of uniting different Christian denominations. The Congregational Union of Ontario and Québec also expressed a desire to work toward union, recognizing it as a worthy aspiration to pursue whenever circumstances allowed. The first significant step toward union was taken in 1875, when various Presbyterian bodies merged to form The Presbyterian Church in Canada. However, many church leaders viewed this as merely an initial phase in a broader movement toward a more far-reaching union. A similar union process occurred among Methodists, culminating in the establishment of the Methodist Church of Canada in 1884, with the Congregationalists uniting two decades later. By the end of the 19th century, the notion of a more inclusive Protestant union had gained momentum, particularly among church leaders who recognized the practical and missiological benefits of such an endeavour.

The formal push for church union began earnestly in the early 20th century. In 1902, the Methodist General Conference expressed its desire to unite with the Presbyterian and Congregational Churches. This led to the establishment of a Joint Committee on Church Union in 1904, which brought together representatives from the three denominations to explore the feasibility of an organic union. Over the next four years, the committee tackled key issues concerning the main terms of the Basis of Union, the church's foundational document, and completed its drafting in 1908. The key question posed during discussions was “Do we share a common faith?”4 The theological foundation for the union was rooted in the principles of common convictions and deep spiritual affinities among the uniting churches. The theological preamble to the Basis of Union emphasized this unity, stating that the articles were “the substance of the Christian faith as commonly held among us.” The preamble also affirmed the evangelical doctrines shared by the uniting traditions and presented the statement as “a brief summary of our common faith.” Additionally, the unionists viewed their movement as aligning with the Reformation's emphasis on the authority of scripture and the importance of ancient creeds. They maintained their allegiance to the Reformation's evangelical doctrines and rejected the idea that denominational competition was better than establishing a national church – not state controlled but providing “friendly service to the whole nation.”5 Furthermore, the theological foundation was intertwined with a vision for nation-building.6 The United Church was viewed as a way to create and sustain a united Canada by fostering a spirit of union rooted in the prayer of Jesus, which serves as a scriptural foundation: “That all may be one” (John 17:21).

While the first draft of the Basis of Union was completed in 1908, local union churches emerged, inspired by its united vision. These churches were deliberately established as independent entities, maintaining connections to parent bodies while remaining distinct from existing denominations in preparation for the anticipated national union.7 They represented a grassroots movement, often in rural or frontier areas of western Canada, where communities sought union to avoid denominational competition and resource duplication.8 By 1912, local union churches formed the General Council of Local Union Churches and created presbyteries. In 1921, they were invited to join the Joint Committee on Church Union. By 1925, they numbered approximately 100 congregations across six presbyteries from Québec to British Columbia. Local union churches were entirely new, interdenominational communities that operated under the newly crafted Basis of Union, maintaining a unique identity distinct from Methodists, Presbyterians, or Congregationalists. They exemplified local enthusiasm for ecumenism, reflecting a desire for practical partnership in Canada's expanding western provinces. Their existence underscored the national union's goal to unite Protestantism beyond bureaucratic negotiations9 and blend grassroots initiatives with top-down structural reform. Their story enriches the narrative of Canadian religious history, illustrating how ordinary congregations shaped a national ecclesiastical vision.

One of the primary challenges of church union was determining the governance structure of the United Church. The three denominations had different administrative traditions – Presbyterians favoured a representative system, Methodists employed a conference-based structure, and Congregationalists emphasized local autonomy – so compromises needed to be made. The result was a unique blend of these traditions, ensuring that all voices would be heard in the new church. Additionally, the legal and financial aspects of the church union required careful planning. Issues such as property ownership, denominational assets, and church governance were among the contentious matters that needed resolution before the union could be formalized. In preparation for the merger, leaders worked to secure government approval and legal recognition. The United Church of Canada Act,10 passed by the Parliament of Canada in 1924, provided the legal framework for the creation of The United Church of Canada. It ensured that congregations could retain their properties and included provisions allowing non-concurring congregations – particularly from the Presbyterian Church – to remain outside the union and retain their own property. This legal foundation was critical in making the transition as smooth as possible and preventing prolonged litigation over church assets.

The movement was significantly influenced by the challenges posed by increasing immigration and social change.11 Church leaders feared that the influx of non-Protestant immigrants could disrupt Canada's moral and religious fabric.12 They regarded a united (Anglo-Saxon) Protestant church as an essential force in preserving the nation's Christian identity. A significant driving force behind the church union was the desire to overcome “sectarian” divisions within Canadian Protestantism.13 Many viewed denominational rivalry as a barrier to evangelism and a diversion from the church's core mission. The goal of forming a united national church, with a presence in nearly every Canadian community, was to strengthen the Protestant church's mission by fostering greater unity. Church union was seen as a means to eliminate redundant efforts and optimize resources, enabling more effective service to communities.

The United Church of Canada was officially established in Toronto on 10 June 1925, and it was the first of its kind in a Western country in the 20th century.14 A grand ceremony marked the historic inauguration service, bringing together representatives from the uniting denominations. The new church embraced the rich traditions of Methodism, Presbyterianism, and Congregationalism, along with the desires of the local union churches, hallowing the union for the new church.15 The formation of the United Church was a significant milestone in Canadian religious history (see Figure 1). Despite the challenges and opposition,16 the union reflected the aspirations of many Canadian Protestants who sought greater collaboration and efficiency in their mission. The church's focus on inclusivity, social justice, and national service positioned it as a leading force in Canadian religious and social life.

Source: https://united-church.ca/sites/default/files/ucc-family-tree.pdf

After the church union, the Executive Committee of the Joint Committee on Church Union stated, “The present Union, now consummated, is but another step toward the wider union of Evangelical Churches, not only in Canada but throughout the world.”17 There are now over 50 United and Uniting churches worldwide. While many of these churches continue to be members of the Christian World Communions to which their "parent" churches belonged, they have also developed their own identity and structure as a communion of “United and Uniting Churches” through a series of consultations facilitated by the World Council of Churches (WCC).18

In Canada, another significant step toward union was taken in 1968 after years of discussion: The Evangelical United Brethren (EUB) Church in Canada united with The United Church of Canada.19 The EUB had deep roots in the 18th-century evangelical movements established by German-speaking immigrants in North America and was firmly committed to stewardship. Despite some theological concerns, the majority of Canadian EUB members voted in favour of uniting with the United Church.20 This historic union broadened the United Church's presence, strengthening its mission of unity, collaboration, and faith-based service throughout Canada.

Double Vision

The Basis of Union served as a foundational statement outlining the theological and ecclesiastical principles of the church and the vision of creating a national church. However, it did not explicitly convey the church's vision. Amid diversity, three denominational traditions resided under one roof; the church coexisted during trying times. After nearly a decade of living together, it demonstrated resilience and achievement despite facing significant challenges. In 1934, during the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, Congregationalist Claris Edwin Silcox presented a compelling call to action for the church.21 He argued that the church needed to reimagine its role in a rapidly changing world; by revitalizing theology, grounding social engagement in realism, investing in education for both clergy and laity, and rethinking ministry, the United Church could navigate the crises of the 1930s – and beyond – with renewed purpose. His vision, blending progressive idealism with pragmatic realism, remains a poignant reminder that a church grounded in both faith and reason can illuminate the path to personal and societal transformation. In this, the United Church “should concern itself less with ecclesiastical machinery and more with the message and the discipline which constitute the Church of the Holy Quest and the Church of the Living God.”22

The core principle of the Order is “ordered liberty” in worship. It is ordered because it is anchored by the form of apostolic tradition and historical Christian practices, and it is liberty because it is inspired by the free movement of the Holy Spirit, emphasizing a balance between form and freedom in the worship experience. The church recognizes the importance of maintaining a connection to heritage-based worship while allowing flexibility to uphold the Spirit of Christ. By avoiding rigid uniformity, the Order ensures that worship remains a meaningful and dynamic spiritual experience for all of God's people. In the Order, we glimpse the church's vision as it simultaneously embraces form and freedom, as well as reason and faith.In our worship we are rightly concerned for two things: first, that a worshipping congregation of the Lord's people shall be free to follow the leading of the Spirit of Christ in their midst; and secondly, that the experience of many ages of devotion shall not be lost, but preserved – experience that has caused certain forms of prayer to glow with light and power.24

The evolving dynamics of the church's vision for worship can be observed in two later documents: “Christianizing the Social Order” (hereafter “Christianizing”) and “Evangelism,” both presented in 1934.25 These documents were shaped by the turmoil of the Great Depression (1929–39) and contamination by the “poisoned air.”26 The commissioned document “Christianizing” by the Board of Evangelism and Social Service aimed to explore the Christian standards that should govern social life, assess how contemporary economic and political structures aligned with these principles, and determine what actions the church should take to implement Christian ideals within society. The document “Evangelism” was presented by the same committee, providing a comprehensive statement on evangelism. It explores the concept of evangelism, differentiating it from “Christianization” and distancing it from the “territorial expansion of the church's mission” while emphasizing its focus on spiritual renewal.27

In the life of the church, “Evangelism” has been significantly overshadowed by the more well-known “Christianizing.” However, it complements “Christianizing” with a broader vision of renewed evangelism. Here, we observe two distinct but interconnected visions of the United Church. While both address the role of the Christian faith, they differ markedly in emphasis: one, “Christianizing,” prioritizes societal transformation through Christian principles (immanence), whereas the other, “Evangelism,” highlights the spiritual and eternal dimensions of faith (transcendence).28 These documents present two distinct visions for the church, yet they remain united in their pursuit of faithful witness.

“Christianizing” is rooted in an immanent theological perspective. It advocates for the transformation of societal structures based on Christian ethics. This document argues that faith should not be confined to personal spirituality but should actively influence social, economic, and political spheres.29 “Christianizing” portrays Christianity as a force for tangible change, urging believers to engage in social activism and create a just and moral society. Economic justice and structural transformation are central themes, reinforcing the belief that God's presence exists within the world and that Christian principles must shape social institutions.30 In contrast, “Evangelism” adopts a transcendent theological perspective, emphasizing personal salvation, spiritual renewal, and eternity. It addresses the spiritual needs of individuals and society. The document presents the Christian mission as primarily one of preaching the gospel, calling individuals to repentance, and fostering a personal relationship with Christ.

The comparative analysis of these two documents reveals a tension between immanence and transcendence in Christian thought. While both perspectives contribute to the Christian witness, they reflect differing theological emphases: one focusing on societal transformation and the other on spiritual renewal. Together, they illustrate the dual nature of Christian engagement, wherein faith must address both societal justice and spiritual renewal. This understanding is evident in Northrop Frye's posthumous book, The Double Vision.31 According to Frye, it addresses the integration of primary human concerns with spiritual aspirations. Double vision reconciles the material and the spiritual, advocating for a worldview where neither is diminished. The double vision illustrates a dynamic framework that denotes the ability to perceive simultaneously at two distinct levels of reality: the immanent and the transcendent. In other words, Christians envision the world we create within the world we live in. From this perspective, “Christianizing” and “Evangelism” shaped the vision of the young church for its ministry and witness in the years ahead.

Evolving Landscape

Since most members of the United Church had Anglo-Saxon roots, they believed Canada should defend Britain in the Second World War (1939–45), regardless of the sacrifices involved. Consequently, they sought support from their church during these challenging times. During the war, the church actively contributed to the war effort through its War Services Committee, which recruited and provided resources for over 120 military chaplains.32 The church mobilized congregations, particularly the Woman's Missionary Society, to help shape post-war Canadian communities and strengthen the role of women in church-led social service initiatives.33 It also urged members to purchase War Savings Certificates,34 although this financial involvement sparked debate over the church's stance on the war effort. The United Church played a vital role in wartime and post-war Canadian society through chaplaincy, aid programmes, and financial initiatives.

In post-war Canada, the United Church played a crucial role in evangelism and social services, responding to the nation's transition from wartime mobilization to reconstruction. Through its Forward Movement, the church aimed to rekindle faith, foster social responsibility, and strengthen community engagement.35 Recognizing the significant social, economic, and political changes ahead, it emphasized spreading the gospel and making disciples. While the heightened interest in Christian doctrine and evangelism experiments offered promise, challenges such as racial hostility and social tensions persisted. The church called for a renewed focus on repentance, social justice, and reconciliation, urging Christians to support one another and address moral and cultural crises. This initiative sought to create a dynamic, unified approach to evangelism, ensuring the church remained relevant and responsive in a rapidly changing society.

As in other Western nations, in Canada the years following the war were pivotal, marked by economic growth, suburban expansion, and increased immigration. Among the most significant developments was the rise of the welfare state, particularly in the 1960s, which redefined the role of government in society. As governments assumed greater responsibility for health care, education, and social welfare, the visible role of churches in public life diminished. Economic prosperity fuelled industrial expansion and consumerism, enabling many Canadians to relocate to suburban communities. Simultaneously, waves of post-war immigration – first from Europe and later from more diverse global regions – contributed to significant cultural and demographic shifts. These changes heightened the demand for public services, resulting in a larger government presence in the social welfare state.

Between 1945 and the 1970s, the federal government's workforce tripled, from 115,908 to 319,605, as it expanded services.36 Key developments included the introduction of the Canada Pension Plan (CPP, 1965), the Medical Care Act (universal healthcare, 1966), and enhanced public education. These programmes improved living standards and reinforced the expectation that the state, rather than religious institutions, would provide essential social services. Historically, churches played a crucial role in education, health care, and charity, but their influence declined as the government took over these responsibilities and service areas. State-funded schools and hospitals replaced church-run institutions, and trends of secularization further diminished religious participation in public affairs. The United Church once operated up to 32 hospitals and medical clinics nationwide.37 This occurred when public health care funding was limited or nonexistent, resulting in many rural and remote communities lacking adequate medical services. The Woman's Missionary Society and the Board of Home Missions initially financed and oversaw this work. However, after the government took control of health care, the number of hospitals and clinics significantly decreased to just ten by the late 1960s.

Paradigm Shifts

In 1962, the same year the Roman Catholic Church convened the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), the United Church approved the establishment of a Commission on World Mission. This commission was tasked with conducting “an independent and fundamental study of how the United Church of Canada can best share in the World Mission of the Church.”38 After two and a half years of study and consultation, it presented its findings in World Mission: Report of the Commission on World Mission to the 22nd General Council in 1966. Emerging during a profound denominational and global shifting landscape,39 the report marked a radical departure from traditional mission strategies rooted in colonial-era paternalism. The report's significance lies in its rejection of ecclesiastical colonialism, adoption of the missio Dei concept, emphasis on religious pluralism, and advocacy for a mission rooted in social justice and shared concerns. Just as the Second Vatican Council produced Nostra aetate for the Roman Catholic Church, World Mission serves as a defining document for the United Church.

One of the report's most ground-breaking contributions was its explicit rejection of “all forms of ecclesiastical colonialism.”40 Historically, missionary efforts by Western churches operated on a parent-child model, wherein Western missionaries dictated theological, administrative, and cultural norms to indigenous churches. However, as many nations gained independence from colonial rule, the United Church reaffirmed the need to move away from hierarchical relationships toward a partnership model.41 The report championed an egalitarian approach, emphasizing collaboration with indigenous churches as autonomous and self-sufficient entities rather than as subordinate extensions of Western Christianity. By prioritizing local leadership and shared decision-making, the report redefined mission as a mutual exchange rather than a one-directional effort.

The World Mission report was among the first church documents to formally embrace the theological concept of missio Dei – the idea that mission is not a project of the church but rather an ongoing activity of God in the world.42 Prior to this, Christian mission was often understood as the work of the church bringing salvation to non-Christian populations. The missio Dei framework, however, reorients the focus away from institutional expansion and toward participation in God's broader redemptive work, which encompasses social justice, reconciliation, and global partnership. This theological shift underscored the belief that the church exists not as the owner of mission but as a participant in God's mission that is already at work throughout the world.43

A particularly revolutionary aspect of the World Mission report was its recognition of religious pluralism as a reality that must shape mission practice.44 Rather than viewing non-Christian religions as obstacles to be overcome, the report acknowledged that “God is creatively and redemptively at work in the religious life of all mankind.”45 This statement represented a major departure from exclusive (replacement) and inclusive (fulfilment) theological perspectives on interreligious dialogue that regarded Christianity as the sole path to salvation. The document proposed that meaningful dialogue with other faith traditions was a necessary theological imperative, as it could lead to deeper mutual understanding and partnership.46 This approach aligned with the broader ecumenical movement of the 20th century and anticipated later interreligious engagement with people of all religious backgrounds.

Another key contribution of the World Mission report was its emphasis on mission as a response to shared concern for justice rather than a tool for religious conversion. The report introduced the concept of “shared concern,”47 which emphasized addressing common social struggles – such as poverty, inequality, and injustice – as a uniting basis for mission work. This approach recognized that Christians and non-Christians alike could work together in solidarity to confront global challenges. It reframed mission as a collective effort aimed at improving human dignity and social conditions rather than merely as a means of expanding church membership. By advocating for mission practices grounded in justice and community empowerment, the report reinforced the idea that the role of the church was to stand in solidarity with marginalized people rather than dominate them. The World Mission report remains a cornerstone of the United Church's missiology, influencing subsequent policies and ecumenical initiatives. Its emphasis on partnership, equity, and humanity continues to shape the United Church's missiology today.

Human sexuality

Same-sex marriage has been a significant social and religious issue, leading to legal and theological debates worldwide.48 While many religious institutions initially resisted recognizing same-sex relationships, the United Church played a pivotal role in advocating for 2SLGBTQIA+ rights and dignity.49 The church's journey from rejecting homosexuality to becoming one of the world's most affirming Christian denominations reflects a broader societal shift toward embracing all forms of human sexuality. For much of history, same-sex relationships were considered immoral. In 1960, the United Church declared, “homosexual activity is a sin against the self.”50 However, by the 1980s, changing social attitudes prompted the church to re-examine its stance, leading to a historic decision later in that decade.

In 1988, the 32nd General Council of the United Church made a ground-breaking statement: “Sexual orientation is therefore not a barrier to such consideration,” affirming full participation in church life, including ordination.51 This move was one of the first of its kind among major Christian denominations, marking a significant departure from the church's earlier views. The decision acknowledged the history of persecution and discrimination against a diversity of sexualities and genders, recognizing the church's need to engage in further theological affirmation that gender and sexuality are gifts from God.

The 1988 decision, however, was met with strong resistance. Some congregations and members left the church, while others formed protest groups such as the Community of Concern. Despite these challenges, the church stood firm in its commitment to inclusivity, demonstrating that religious institutions could evolve to reflect new understandings of human sexuality. Although LGBTQ+ inclusion was affirmed, discrimination persisted. By 2000, the 37th General Council further strengthened LGBTQ+ inclusion, affirming that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identities are “gifts from God.”52 The church also formally recognized same-sex partnerships and pledged to work for their civil recognition. As Canada moved toward legalizing same-sex marriage in 2003, the United Church became one of the first Christian denominations to officially support it.53 The church actively lobbied for legal recognition, advocating for equal marriage rights as a matter of faith and justice. Recognizing its past mistakes, the United Church formally apologized to 2SLGBTQ+ members in 2014.54 This apology acknowledged the historical harm caused by homophobia, exclusion, and discrimination within the church. As the global conversation on 2SLGBTQIA+ rights continues, the role of faith communities remains crucial.55 The experience of the United Church serves as a powerful example of how religious institutions can evolve to embrace inclusivity and affirm the dignity of all individuals. The church's efforts in reconciliation and advocacy demonstrate that faith and justice can coexist, shaping a more compassionate and equitable society for current and future generations.

Holistic ecumenism

Mending the World (1997) presented a transformative vision of healing and reconciliation grounded in World Mission.56 It called on the United Church to move beyond traditional ecumenism, which focuses on Christian unity, toward whole-world ecumenism, engaging with individuals of all faiths and backgrounds to promote justice, healing, and sustainability. At its core, Mending the World affirmed that God's primary concern is the restoration of creation and human relationships.57 Rooted in biblical teachings, it stressed that the United Church must align itself with missio Dei: not for institutional preservation but for the transformation of the world. It challenged the church to collaborate with all people of goodwill – Christians, individuals of other faiths, and secular organizations – to tackle pressing global issues, such as poverty, violence, environmental destruction, and inequality. Mending the World, stemming from extensive consultation, reaffirmed that the church's mission is not about self-defence but about striving for the common good. It urged congregations to evaluate their mission through this lens, seek partnerships across religious and secular lines, and commit to God's work of healing and renewal. Ultimately, Mending the World envisioned the church's ecumenism and mission as a uniting force, working across divisions to bring justice, healing, and hope to the world.

Interreligious dialogue

As discussed, World Mission (1966) moved beyond the Christocentric approach to interreligious dialogue and presented a new understanding of its relations with other faiths in a religiously pluralistic world. However, the move was not an easy one: The church initially struggled with interreligious dialogue due to its Christocentric approach, which viewed Jesus as the completion of God's promises. This approach limited engagement with other faiths, leading to the conflicted reception of Bearing Faithful Witness: United Church–Jewish Relations Today in 1997,58 a report that aimed to foster dialogue with Jewish communities. The main opposition arose from many within the church who upheld an exclusivist perspective. However, a revised version was later accepted in 2003, embracing a dual-covenant theology, affirming both the Torah and the gospel as expressions of God's love.59 This marked a shift from a Christocentric approach to a theocentric perspective, acknowledging Judaism and Christianity as distinct while remaining equally valid paths to God.

Learning from this experience, the United Church adopted a similar theocentric approach in That We May Know Each Other: United Church–Muslim Relations Today (2006),60 which framed interreligious dialogue with Islam. This report was influenced by World Mission (1966), emphasizing that God works redemptively in all religions. It affirmed shared beliefs between Christians and Muslims, recognizing Muhammad's prophetic role and the Qur'an as the word of God. Ten years later, the United Church explored its evolving relationship with Hindu communities in Honouring the Divine in Each Other: United Church–Hindu Relations Today (2016).61 It acknowledged past missionary condemnation of Hindu practices and colonial biases, expressing regret while affirming respect for Hinduism's rich traditions. The document emphasizes a pluralistic approach, recognizing the presence of divine truth in Hinduism and advocating for mutual understanding and transformation. Through these evolving reports, the church gradually moved toward a theological framework that respects religious plurality, acknowledging multiple paths to the divine beyond Christianity.

Building right relations

The history of the residential school system in Canada remains a defining chapter in the nation's relationship with Indigenous peoples. This system, operating from the 1880s to 1990s, was driven by government policies aimed at forced assimilation, stripping Indigenous children of their cultural identities, languages, and familial ties.62 In the early 20th century, a Methodist superintendent of Indian education confirmed through his 15-year experience that “it is possible to civilize him; that it is possible to educate him; that it is possible to Christianize him.”63 The government and church leaders believed that both civilizing and Christianizing goals would be achieved through the residential schools. However, the aims of Christianity and good citizenship required close collaboration between the church and the state.64 Operating under this assumption, the church participated in running 16 Indian Residential Schools established by its Methodist and Presbyterian predecessors, with the last of these schools remaining in operation until 1973.

The United Church has issued multiple apologies, recognizing its past injustices toward Indigenous peoples. These statements, made in 1986, 1998, and reaffirmed through the 2012 crest revision, mark important steps toward reconciliation. In 1986, the church admitted that, in spreading Christianity, it had dismissed Indigenous spirituality and imposed Western ways, damaging both Indigenous identity and the church itself. It sought forgiveness and a renewed relationship based on respect and shared faith. In 1988, Indigenous representatives responded, acknowledging the apology while emphasizing that true reconciliation required action. They urged respect for Indigenous traditions and peaceful coexistence.

The 1998 apology directly addressed the church's role in the Indian Residential School system, recognizing the suffering caused by forced assimilation and abuse. The church offered a sincere apology to the families and communities affected by residential schools, seeking “God's forgiveness and healing grace as we take steps toward building respectful, compassionate, and loving relationships with First Nations peoples.”65 In 2012, the church revised its crest to reflect Indigenous inclusion, incorporating the four colours of the medicine wheel and adding “Akwe Nia'Tetewá:neren,” a Mohawk phrase meaning “All my relations.” This symbolic change recognized the historical and spiritual presence of Indigenous peoples within the church. However, while apologies and actions mark progress, reconciliation is an ongoing process. Indigenous voices continue to call for action and meaningful change.

The worldview of “All my relations” reflects a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of all life forms, emphasizing that humans are not separate from nature but are part of a larger ecological web. This wisdom aligns closely with environmental ethics and sustainability by advocating for reciprocal relationships with the land, animals, water, and all living beings. In 1992, the church issued the document “One Earth Community: Ethical Principles for Environment and Development,” in response to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro.66 It outlines a vision where humanity is interconnected with nature and must act as responsible stewards, emphasizing justice, sustainability, and ecological respect. As Canada confronts escalating climate challenges, Indigenous-led movements for environmental justice have emerged as powerful forces for change. Despite centuries of colonial oppression, Indigenous communities remain at the forefront of climate action, advocating for policies that recognize the depth and significance of traditional ecological knowledge.67 These practices are essential not only for mitigating climate change but also for providing solutions that exceed the extractive, short-term approaches of Western environmental policy, building right relations with creation.

An Intercultural and Anti-Racist Church

The desire to be a national church in Canada was deeply intertwined with the nation's identity, especially during the period of the church's formation. Protestant church leaders felt it was their duty to establish the moral and spiritual foundations of the nation and to ensure that Canada remained a Christian society. One major driving factor for church union was the challenge posed by immigration. Church leaders aimed to assimilate these newcomers into Anglo-Saxon Christian values through public education and religious instruction, reinforcing the belief that Canadianization and Christianization were inseparable.

Since the late 1980s, the United Church has acknowledged the need to confront racism both within the church and in society.68 In its report to the 36th General Council (1997), the church formally committed to ending racism, allocating resources to support this goal. This commitment shaped That All May Be One: Policy Statement on Anti-Racism, presented to the 37th General Council (2000).69 The statement of beliefs emphasized key principles: all people are equal before God, racism is deeply embedded in both society and the church, and addressing it requires continuous effort. The church acknowledged that its anti-racism policy was only a starting point intended to create a truly inclusive community where differences are embraced. It affirmed that change is possible and called on its members to work toward a society where the gospel's message of justice is fully realized.

The church's declaration that “racism is a sin” reinforced its commitment to dismantling racial injustice.70 It recognized that a community seeking to welcome cultural differences could not be built on the foundations of systemic racism. This prompted deeper reflection on how to engage meaningfully with racial justice beyond mere symbolic commitments. Between 2005 and 2006, the Ethnic Ministries Re-visioning Task Group (RTG) conducted a re-visioning process to strengthen the church's commitment to racial justice.71 The RTG emphasized that the church's ministry must be built on racial justice to fulfill the hopes of diverse communities. It stressed the need for more church members to actively engage in the transformational work of systemic change.

Notably, the RTG avoided using the term “multicultural church,” stating that while celebrating diversity is important, it is only the beginning. It described the term as problematic and instead promoted the idea of an intercultural church, one that fosters deeper engagement and mutual transformation rather than mere representation. The 39th General Council (2006) declared that the “church must be intercultural.”72 The Ethnic Ministries Unit of the General Council proposed a vision for the church “where there is mutually respectful diversity and full and equitable participation of all Aboriginal, Francophone, ethnic minority, and ethnic majority constituencies in the total life, mission, and practices of the whole church.”73 The church's vision at that time suggested that all people within the church, regardless of their racial and cultural backgrounds, be invited to participate equally in building mutual relations in its life and work. The church strives to create a welcoming and safe space for all, envisioning itself as an intercultural church that fosters a community rooted in equity, justice and love.74

Drawing the Circle Wide

Since its inception, the United Church has long been committed to fostering ecumenical relationships with global Christian communities. The 42nd General Council (2015) approved the endeavour “Mutual Agreement” and “Full Communion,” which outlines the church's efforts to establish mutual recognition of ministry with the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) and the Presbyterian Church in the Republic of Korea (PROK), as well as a full communion agreement with the United Church of Christ (USA).75 These initiatives reflect the United Church's dedication to unity in Christ and to strengthening its mission in an increasingly interconnected world.

The background of these agreements highlights the historical and theological connections among these churches. The United Church has maintained a long-standing relationship with the UCCP and PROK, supporting their ministries and recognizing their unique challenges. The UCCP, for instance, emerged in 1948 from a merger of five denominations and has been navigating the complexities of national diversity and international partnerships ever since. Similarly, the PROK, formed in 1953, has maintained a close connection with the United Church, rooted in shared theological perspectives and a commitment to justice and peace.76

The full communion agreement with the United Church of Christ (USA) marks another milestone in the church's ecumenical efforts. This agreement not only facilitates ministerial exchanges but also commits both churches to joint theological study, social justice initiatives, and shared worship experiences. The full communion agreement is grounded in a shared history and a common vision of a united church that embraces diversity and inclusivity. It reflects a biblical and theological commitment to the unity of the body of Christ. These agreements represent a significant step toward realizing Jesus’ prayer, “that all may be one.” They embody the ecumenical spirit, emphasizing partnership over division and shared mission over isolated ministry. By fostering mutual recognition of ministry and establishing full communion, the United Church and its partner churches reaffirm their commitment to being a visible sign of unity within the global Christian community.

Closing Remarks

Liberal churches, including the United Church, have long been at the forefront of progressive social change, advocating for racial and gender justice, 2SLGBTQ+ rights, interreligious relations, and broader social inclusion. However, as these values have increasingly become prevalent in secular society,77 liberal churches now face a paradox: their cultural triumph has coincided with institutional decline.78 The principles championed by liberal Protestantism – inclusion, tolerance, pluralism, and critical inquiry – have become so ingrained in Western culture that the churches that once promoted them now struggle to justify their distinct existence.

This phenomenon, often referred to as “cultural victory and organizational defeat,”79 indicates that liberal churches have successfully reshaped social values but have done so at the expense of their institutional vitality. Many of the moral and ethical positions once linked to liberal Christian values are now widely adopted by secular institutions, making religious affiliation seem redundant for those who share these values. As a result, younger generations, particularly millennials, often find no compelling reason to engage with church communities, especially when they perceive spirituality as a personal rather than a communal pursuit.80 Furthermore, liberal churches often stress theological openness and doctrinal flexibility, which, while appealing in principle, can result in a lack of institutional cohesion and commitment.

In this sense, are liberal churches indeed victims of their success? Their advocacy for justice and inclusion has helped shape a more equitable society and spread Christian values. In doing so, they have contributed to a world where their institutional presence provides transformative influence. Moving forward, the challenge for liberal churches is to redefine their relevance – not only for advocates of progressive Christian values but also for communities that provide deep spiritual formation, meaningful rituals, and a sense of belonging that secular institutions cannot easily replicate. Recalling Frye's “double vision,” which encompasses the immanent and transcendent nature of God, we, The United Church of Canada, hold fast to the founding vision articulated in “Christianizing the Social Order” and “Evangelism.” We realize this vision through the church's new call and vision: “Deep Spirituality, Bold Discipleship, and Daring Justice.”81

- 1 Due to space constraints, this article primarily examines the history of The United Church of Canada's domestic life and work. For insights into the church's overseas mission, please see my article “Mission Beyond Canada,” in The Theology of The United Church of Canada, ed. Don Schweitzer, Robert C. Fennell, and Michael Bourgeois (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2019), 251–77.

- 2 The United Church of Canada (hereafter UCC), “The Formation of the United Church of Canada,” The Manual, 2025, 12.

- 3 UCC, “Joint Committee on Church Union: Historical Statement,” Proceedings, GC1 (1925), 57.

- 4 Phyllis Airhart, A Church with the Soul of a Nation: Making and Remaking the United Church of Canada (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2014), 22.

- 5 UCC, “Report of Home Missions and Social Service,” The United Church of Canada Year Book (1926), 330. Quoted in Airhart, Church with the Soul of a Nation, 5.

- 6 George C. Pidgeon, Nation Building: A Review of the Work of Home Missions and Social Service (Toronto: Board of Home Mission and Social Service, 1917).

- 7 C. E. Manning, “Church Union and Union Churches: Interesting Meeting of the Local Union,” The Christian Guardian (2 August 1922), 9.

- 8 Western Methodist Recorder (May 1913), 10–11. “The purpose of local union churches in small centers is to have one large congregation and much unnecessary duplication of money and effort. It was decided not to place three churches under any one denomination or to give them a denominational name.”

- 9 Suggested Plan for Local Union Churches: In affiliation with either the Presbyterian Church, the Methodist Church or the Congregational Union of Church, 1917.

- 10 Canada, United Church of Canada Act (19 July 1924), http://axz.ca/act.htm.

- 11 Barry Edmonston, “Canada's Immigration Trends and Patterns,” Canadian Studies in Population 43:1–2 (2016), 78.

- 12 S. D. Chown, “How Shall the Foreigners Govern Us?” The Christian Guardian (23 February 1910), 8; J. S. Woodsworth, Strangers within Our Gates; Or Coming Canadians (Ontario: F. C. Stephenson, 1909). Woodsworth categorized immigrants by race and ethnicity, ranking some groups as more “desirable” than others. He believed that northern and Western Europeans were preferable immigrants, while he was skeptical or outright hostile toward non-white immigrants, particularly Asians and Eastern Europeans.

- 13 UCC, “Joint Committee on Church Union: The Executive Committee,” Proceedings, GC1 (1925), 62.

- 14 John Webster Grant, “What's Past Is Prologue,” in Voices & Visions: 65 Years of the United Church of Canada, ed. John Webster Grant et al. (Toronto: UCPH, 1990), 125.

- 15 UCC, The Inaugural Service of the United Church of Canada (10 June 1925), 20–24.

- 16 While many welcomed the prospect of union, opposition remained, particularly within the Presbyterian Church. A substantial faction of Presbyterians argued that the union would compromise their theological heritage and governance structure. Ephraim Scott, “Church Union” and the Presbyterian Church in Canada (Montreal: John Lovell and Son, 1928), 104–107.

- 17 UCC, “Joint Committee on Church Union: Historical Statement,” Proceedings, GC1 (1925), 57.

- 18 World Council of Churches, “United and Uniting Churches,” https://www.oikoumene.org/church-families/united-and-uniting-churches; World Council of Churches Commission on Faith and Order, United and Uniting Churches: Two Messages, Faith and Order Paper, No. 225 (Geneva: WCC Publications, 2019), https://www.oikoumene.org/resources/publications/united-and-uniting-churches-two-messages.

- 19 UCC, “Committee on Union,” Proceedings, GC23 (1968), 50, 452–54.

- 20 John Burbidge, “Gentle Shepherd of 10,000 Brethren,” The United Church Observer (UCO) (1 January 1968), 10–12, 29.

- 21 Claris Edwin Silcox, “The Next Ten Years,” New Outlook (12 September 1934), 776–78, 790.

- 22 Silcox, “The Next Ten Years,” 790, his italics.

- 23 UCC, The Book of Common Order of the United Church of Canada (Toronto: UCPH, 1932).

- 24 UCC, Book of Common Order, iii.

- 25 UCC, “Christianizing the Social Order: A Statement Prepared by a Commission Appointed by the Board of Evangelism and Social Service,” Proceedings, GC6 (1934), 235–48; and UCC, “Evangelism,” Proceedings, GC6 (1934), 252–62.

- 26 UCC, “Evangelism,” 262. The “poisoned air” was used metaphorically to describe the corrosive intellectual and moral atmosphere that had led to a decline in faith and spiritual life. The document discusses how modern materialism, loss of belief in God, and societal structures based on possession had eroded traditional religious values.

- 27 UCC, “Evangelism,” 252.

- 28 UCC, “Christianizing the Social Order,” 238; UCC, “Evangelism,” 256.

- 29 UCC, “Christianizing the Social Order,” 237–48.

- 30 “Christianizing the Social Order” is historically conditioned in that it presents a Western perspective, assuming the superiority of Christian values in societal reform. Although it critiques industrial capitalism, it neglects colonial exploitation. By focusing on domestic issues, it overlooks colonialism's impact on Indigenous and colonized peoples, thereby reinforcing a colonial mindset that prioritizes Western norms over others.

- 31 Northrop Frye, The Double Vision: Language and Meaning of Religion (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1991). This was his last effort to make an accessible version of his longer books, The Great Code and Words with Power – one that would relate the Bible to secular culture.

- 32 UCC, “Report of War Service Committee,” Proceedings, GC10 (1942), 190–91.

- 33 Jean Gordon Forbes, Wide Windows: The Story of the Woman's Missionary Society of the United Church of Canada (Toronto: Woman's Missionary Society, 1951), 130–35.

- 34 UCC, “Report of War Service Committee,” Proceedings, GC9 (1940), 42 and 51.

- 35 UCC, “Forward Movement after the War,” Proceedings, GC11 (1944), 114–20.

- 36 Sandra Beardsall, “‘And Whether Pigs Have Wings’: The United Church in the 1960s,” in The Theology of The United Church of Canada, ed. Don Schweitzer, Robert C. Fennell, and Michael Bourgeois (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2019), 99; Colin Campbell, Canadian Political Facts 1945–1976 (Toronto: Methuen, 1977), 52.

- 37 Bob Burrows, Healing in the Wilderness: A History of the United Church Mission Hospitals (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2004), 234–35; Mike Milne, “Condition Critical,” UCO (December 2013), 35–37.

- 38 UCC, “World Mission,” Proceedings, GC20 (1962), 298.

- 39 Hyuk Cho, “‘To Share in God's Concern for All’: The Effect of the 1966 Report on World Mission,” Touchstone 27:2 (May 2009), 39–46.

- 40 UCC, World Mission: Report of the Commission on World Mission (Toronto: UCC, 1966), 136.

- 41 In the United Church, this change in mission relationship can be observed from the 1930s. See Hyuk Cho, “Practising God's Mission Beyond Canada,” in The Theology of The United Church of Canada, ed. Don Schweitzer, Robert C. Fennell, and Michael Bourgeois (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018), 253–57.

- 42 WCC, The Church of Others and the Church for the World (Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1967).

- 43 Hyuk Cho, “Never-Ending Mission of God: The Evolution of the Concept of Missio Dei in Our Ever-Changing Landscape,” International Review of Mission 113:1 (May 2024), 173–90.

- 44 UCC, World Mission, 25.

- 45 UCC, World Mission, 137.

- 46 UCC, World Mission, 124.

- 47 UCC, World Mission, 54.

- 48 During the 2023 central committee meeting of the World Council of Churches, human sexuality emerged as one of the most contentious issues.

- 49 UCC, “Call to Act: Join in Solidarity with the 2SLGBTQIA+ Community,” https://united-church.ca/news/call-act-join-solidarity-2slgbtqia-community.

- 50 UCC, “Commission on Christian Marriage and Divorce,” Proceedings, GC9 (1960), 163.

- 51 UCC, “Sexual Orientations, Lifestyles and Ministry,” Proceedings, GC32 (1988), 105.

- 52 UCC, “Human Sexual Orientation Issues,” Proceedings, GC37 (2000), 166.

- 53 Pamela Dickey Young, “Same-Sex Marriage and the Christian Churches in Canada,” Studies in Religion 35:1 (2006), 3–23.

- 54 UCC, “Apology to Members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two-Spirit, Trans, and Queer (LGBTQ) Communities,” Executive of General Council (15–17 November 2014), 143–49.

- 55 UCC Foundation, “2SLGBTQIA+ Global Solidarity Fund,” https://unitedchurchfoundation.ca/giving/explore-funds/lgbtiq2s-global-solidarity-fund.

- 56 UCC, Mending the World: An Ecumenical Vision for Healing and Reconciliation, Proceedings, GC36 (1997), 195–227.

- 57 Mending the World echoes World Mission: “God is creatively and redemptively at work in the religious life of all mankind.” It also uses the concept of “shared concern,” with reference to working collaboratively with others for the common good. UCC, Mending the World, 21. See UCC, World Mission, 54.

- 58 UCC, Bearing Faithful Witness: United Church–Jewish Relations Today (Toronto: UCC, 1997).

- 59 UCC, Bearing Faithful Witness: United Church–Jewish Relations Today (Toronto: UCC, 2003).

- 60 UCC, That We May Know Each Other: United Church–Muslim Relations Today (Toronto: UCC, 2006).

- 61 UCC, Honouring the Divine in Each Other: United Church–Hindu Relations Today (Toronto: UCC, 2016).

- 62 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, A Knock on the Door: The Essential History of Residential Schools from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, ed. University of Manitoba, National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2016).

- 63 Thompson Ferrier, Our Indians and Their Training for Citizenship (Toronto: Methodist Mission Rooms, 1913), 21.

- 64 John W. Grant, Moon of Wintertime: Missionaries and the Indians of Canada in Encounter since 1535 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 185.

- 65 UCC, “To Former Students of United Church Indian Residential Schools, and to Their Families and Communities” (General Council Executive, 1998).

- 66 David Hallman, “One Earth Community: Ethical Principles for Environment and Development – A Statement of the 34th General Council of the United Church of Canada” (UCC, 1992). Hallman worked for over 30 years in The United Church of Canada, overseeing various social justice responsibilities. Environmental ethics were a significant part of his portfolio during his career. In addition to his work in the church, he served from 1988 to 2006 as the co-ordinator of the WCC Climate Change Programme based in Geneva, which involved him in UN global negotiations on climate change.

- 67 Martha Pedoniquotte, “Prioritize Indigenous Approaches to Climate Action,” Round the Table (UCC, 18 June 2024), https://united-church.ca/blogs/round-table/prioritize-indigenous-approaches-climate-action. This knowledge – rooted in a holistic worldview that sees land, water, plants, animals, and humans as interconnected – encompasses land-based conservation practices, sustainable resource management, and climate adaptation strategies that have sustained ecosystems for generations.

- 68 UCC, Moving Beyond Racism: Worship Resources and Background Material (Toronto: UCC, 1987) and Exploring Racism (Toronto: UCC, 1989).

- 69 UCC, “That All May Be One: Policy Statement on Anti-Racism,” Proceedings, GC37 (2000), 712–26.

- 70 UCC, “That All May Be One: Policy Statement on Anti-Racism,” 714.

- 71 Ethnic Ministries Re-visioning Task Group, “A Transformative Vision for the United Church of Canada,” 39th General Council (August 2006).

- 72 UCC, Proceedings, GC39 (2006), 748.

- 73 UCC, Proceedings, GC39 (2006), 580.

- 74 For the vision of becoming an intercultural church, see Hyuk Cho, Relation without Relation: Intercultural Theology as Decolonizing Mission Practice (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2025).

- 75 UCC, Proceedings, GC42 (2015), 245–48 and 251–54.

- 76 Hyuk Cho, “Have You Eaten? Decolonizing Theology in the Context of the Philippines and Korea,” International Journal of Asian Christianity 7:2 (August 2024), 191–213. Before the formation of the PROK, the UCC had established a mission relationship in Korea dating back to late 19th century. Since then, over 100 personnel from the UCC have served in Korea, fostering a deep and lasting connection with the PROK. Their efforts have included providing English-language services, promoting interfaith dialogue, and advocating for peace, reunification, and various social justice causes, all while bearing witness to significant moments in Korean history.

- 77 Hyuk Cho, “Beyond Secularism (Laïcité): Québec's Secularism and Religious Participation in Nation-Building,” Religions 16:5 (2005), 2.

- 78 Christian Smith, Souls in Transition: The Religious Spiritual Adults (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 287–92.

- 79 N. J. Demerath, “Cultural Victory and Organizational Defeat in the Paradoxical Decline of Liberal Protestantism,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34:4 (1995), 458–69.

- 80 Reginald W. Bibby, Joel Thiessen, and Monetta Bailey, The Millennial Mosaic: How Pluralism and Choice Are Shaping Canadian Youth and the Future of Canada (Toronto: Dundurn, 2019), 173–99. According to their findings, religious practices among millennials differ significantly from those of previous generations. While many still identify with a religious tradition – primarily Christianity – regular attendance at religious services remains low. Instead, millennials prefer private spiritual practices such as prayer and online religious engagement. Digital platforms have created new avenues for religious expression, allowing individuals to explore faith outside of traditional church settings. This trend suggests that while institutional religion may be declining, faith and spirituality are being redefined rather than completely abandoned.

- 81 UCC, Strategic Plan 2023–2025, (UCC, 2022), https://united-church.ca/sites/default/files/2022-12/strategic-plan-final_nov-2022.pdf.

Biography

Rev. Prof Dr Hyuk Cho is an associate professor of theology and the director of United Church Formation and Studies at the Vancouver School of Theology in Canada. He is an ordained minister of The United Church of Canada and currently serves on the central committee of the World Council of Churches.