More than just a dental practitioner: A realist evaluation of a dental anxiety service in Norway

Funding information:

This study is part of a PhD funded by the Ministry of Health and Care Services.

Abstract

Patients with dental phobia or a history of trauma tend to avoid dental services, which may, over time, lead to poor oral health. In Norway, a specific service targets these patients by providing exposure therapy to treat their fear of attendance and subsequently enable oral restoration. Dental practitioners deliver the exposure therapy, which requires a role change that deviates from their traditional practice. This paper explores how – and under what circumstances – dental practitioners manage this new role of alleviating dental anxiety for patients with a history of trauma or dental phobia. Using a realist evaluation approach, this paper develops theory describing which contexts promote mechanisms that allow practitioners to alleviate dental anxiety for patients with trauma or dental phobia. A multi-method approach, comprising service documents (n = 13) and stakeholder interviews (n = 12), was applied. The data were then analysed through a content analysis and context-mechanism-outcome heuristic tool. Our findings reveal that dental practitioners must adopt roles that enable trust, a safe space, and gradual desensitisation of the patient to their fear triggers. Adopting these roles requires time and resources to develop practitioners' skills – enabling them to adopt an appropriate communication style and exposure pace for each patient.

INTRODUCTION

Dental phobia is an anxiety disorder [1] characterised by a deep, persistent and disproportionate fear of the dental setting. It elicits intense anxiety responses mimicking a panic attack and preventing patients from seeking out or attending dental services [2-4]. Patients with previous trauma – be it physical or emotional and caused by sexual abuse or torture – may likewise avoid dental services, as dental settings remind them of their trauma and psychologically trigger a physiological, cognitive, or emotional response [2, 3, 5-8]. These patients tend to have relational challenges: They struggle to trust dental practitioners and do not feel safe during dental examinations [9-12]. Consequently, dental practitioners tend to meet these patients only for acute dental problems, which then are more severe and complex [3, 13–15].

In light of these psychological triggers, dental practitioners must deal with more than just oral pathologies [11, 16, 17]; they must also address patients' psychological needs. Empirical evidence shows that specialised treatment such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may be effective in alleviating dental anxiety, enabling oral health restoration for trauma and phobic patients [18, 19]. However, to the best of our knowledge, few countries offer services customised for the psychological needs of the type of patients described above, even though this patient group is substantial: in Europe, 8−25% of the population have been subject to physical abuse, 7−22% to sexual abuse, and 13−45% to emotional abuse [20]. There is also increased migration to Europe from countries known to use torture [21, 22]. Prevalence studies on torture survivors in Europe are limited, but in Norway alone, it is estimated that 10,000–35,000 torture survivors reside [23]. In the latter national context, the TADA service (translated abbreviation for torture, abuse, and dental phobia) addresses the shortfall in services for these patients by targeting specifically those subjected to torture or abuse who have been diagnosed with dental phobia. The service includes the psychological intervention of in vivo exposure therapy.

In vivo exposure therapy is a CBT approach relying on direct and active exposure to the dental setting and dental utilities, simulating a 'real-life' scenario. The therapy tests catastrophic thoughts by stimulating an initial, less intense fear response. This desensitises the patient and is the treatment choice for specific phobias [7, 18, 19, 24, 25]. The TADA service, through the inclusion of exposure therapy, has two intended outcomes: first, to alleviate dental anxiety, and subsequently, to restore oral health.

Therapeutic interventions are in the psychological domain and are primarily administered by a psychologist [18, 19]. However, using dental practitioners in a natural real-world clinical setting is logistically and therapeutically advantageous [2]. However, only a few studies are available that explore how dentists include CBT sessions in their dental routines [26-29]. These studies recommend one to five exposure sessions administered by a dental practitioner and find that dental practitioners applying this therapy successfully alleviate patient's dental anxiety, indicating that dental practitioners can address psychological needs through CBT [26-29].

The TADA service consists of interdisciplinary teams of both psychologists and dental practitioners. The psychologists oversee dental practitioners’ training in exposure therapy while dental practitioners execute the therapy. Psychologists are available to guide the dental practitioners if the latter are unsure of patients' responses to the therapy or worried about re-traumatisation. Psychologists are in charge of initial patient screening, assessing whether they meet the diagnostical criteria of dental phobia according to the Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V (DSM-V) [24]. Seven diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-V relate to pathological responses impairing daily routines, or social or occupational life. The pathological responses are emotional, cognitive, and physical in character, and include avoidance behaviour, catastrophic thinking, feeling powerless, fear of losing control, chest pain, trembling, racing heartbeat, nausea, and trouble breathing.

These responses may arise for patients with a history of trauma because the dental setting can be reminiscent of the trauma incident, for example, in having an authoritative figure hovering over them while they are lowered in the chair, with a bright light shining directly above their face, and sharp tools administered in their mouth without their control [30]. However, this link between the trauma incident and the dental setting is not always present [10, 16, 31].

There is some differentiation in the screening of patients to be admitted to the TADA service, dependent on the nature of their trauma history. For example, the service distinguishes between torture and abuse survivors, with abuse survivors having to display at least one phobic response as outlined in the DSM-V anxiety assessment, whilst torture survivors do not need this. However, all patients admitted to the service receive exposure therapy and therefore, in this study, we define and refer to the entire patient population receiving the service as TADA patients. The service is currently free of charge, eliminating cost as a barrier to patient attendance.

None of the studies exploring how CBT applied by dental practitioners [26-29] investigate the role change required by those practitioners to attend to patient's psychological needs. This new role, a change from focusing on mouth pathologies to anxiety triggers, is outside the remit or competence of most dental practitioners since psychology is not a required subject in dental schools [32, 33]. It is also potentially problematic; the culture of dental care being influenced by performance-led actions rather than relational aspects. Thus, there is a need to better understand how dental practitioners must divert from their traditional profession to deliver psychological interventions. Hence, this study aims to explore how, and under what circumstances, dental practitioners are alleviating dental anxiety by delivering exposure therapy for patients with a history of trauma or a dental phobia using a realist evaluation approach.

Realist evaluations address the question of 'what works, for whom, in what circumstances' [34, 35]. The realist evaluation methodology is increasingly popular in health service research [35], as it captures the complexities of services by articulating the contexts and mechanisms through which service outcomes are achieved [34-36] and seeks to address these issues through a theory-driven approach [37].

A theory explaining how the service works is developed and tested by generating an understanding of the interplay between contexts (answering the question of Who and in what circumstances?), mechanisms (a pairing of resources and reasonings – answering How and why?), and outcomes (What works?). This interplay reveals a causal chain – described as a context-mechanism-outcome configuration [35]. The research question in this study was formulated in a realist manner, as were the methodological choices. To operationalise this research question, research sub-questions were phrased and are presented in Table 1.

| Component | Realist evaluation framework |

|---|---|

| Context | The realist researcher seeks to understand a service's workings based on the context into which the service is introduced. The assumption is that operating mechanisms, leading to outcomes, are contingent on these contextual elements. To uncover the contextual elements, the researcher looks into the institutional setting, social interactions, interrelationships and political agendas. These are all background factors describing the contingency to the mechanism and enhancing the understanding of the ‘for whom in what circumstances’. In this research study, the first research questions are: What conditional elements or contextual components are particular to the TADA environment? What is unique to the TADA service's background, that allows the functional mechanisms within it to trigger? |

| Mechanism | The realist researcher searches to uncover ‘why and how’ a programme has observable outcomes. They do so by uncovering generative and causal mechanisms. The concept of the mechanism has two main features: resources and reasoning. The researcher thus explores the programme resources introduced into a particular context, to then understand the response and reasonings behind stakeholders introducing or using these resources in a particular way. Here, the research questions are thus: What unique resources are introduced through the TADA service? How do these resources, provided by the TADA service, impact on the behaviours, assumptions, values and beliefs of dental practitioners when interacting with these resources? Furthermore, what is being triggered in the TADA service, leading to any one particular outcome? |

| Outcome | The outcome describes what the generative mechanism leads to, in the specific context. It is the observable result seen in the service parameters. The research questions are: What does the triggered mechanism lead to? What are the resultant outcomes when a particular mechanism is triggered? Within the TADA service, which outcomes are the dental practitioners observing? What change is the TADA service experiencing? |

A central concept in realist evaluations is that services are theory incarnate, that is, that there is an underlying theory held by the stakeholders involved that steer the service in a direction to reach its desired outcomes. Therefore, the first step of a realist evaluation is to elicit this underlying theory by defining the initial programme theory [37]. The initial programme theory informs the study design and what types of data are of interest to further inform and refine the programme theory. The steps of a realist evaluation are cyclical. Once the initial programme theory is described, data are collected to inform and refine this programme theory accordingly. The informed and refined initial programme theory is programme specific. There is no strict rule in eliciting the initial programme theory; the initial programme theory can emerge from service documents, stakeholder interviews or previous literature. Our initial programme theory was elicited through the main service document provided by the Norwegian Directorate of Health [38], which asserts that a treatment intervention based on CBT principles, specifically using exposure therapy, for patients with a history of trauma (resulting from torture or abuse) or dental phobia (context) will alleviate their associated dental anxiety (mechanism), enabling them to attend oral restoration (outcome).

This paper reports on findings that refine this initial programme theory, now that the service is in place, through a realist evaluation of the TADA service. Some of the findings of the realist evaluation relate to how the TADA service's structural features work, for whom and under which circumstances, and are reported elsewhere (preprint available at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-279468/v1). This paper reports instead on the role of the dental practitioner role in this service as they perform this new psychological role of exposure therapist.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A multi-method design consisting of semi-structured interviews and document analysis was undertaken.

Stakeholder interviews and service documents

In realist terms, stakeholders are key individuals possessing details that inform and refine the initial programme theory [34, 35, 39]. Via purposive and snowballing procedures [40, 41], we recruited stakeholders – using the main TADA service specification document [38] as a starting point. The stakeholders recruited were dental practitioners, psychologists, and managerial staff of the TADA service, covering all regions in Norway. All stakeholders had participated in conceiving and implementing the TADA service and were active in some part of delivering the service at the time of the interview.

A total of 13 informants were identified as possessing relevant information, leading to 12 interviews. Seven of the 13 had a background in dentistry; the remaining six had a psychology background.

The first author conducted all interviews, which were transcribed verbatim immediately afterwards. The interviews were realist informed, such that the interview guide was built around the initial programme theory yet was exploratory in nature, including questions on other aspects of the service (e.g., service structures and collaborations). Interviews were semi-structured, allowing follow-up questions to emerge that explored some of the key assumptions the stakeholders held about how they thought the service functioned. The semi-structured nature of the interview, through comments and clarifications, allowed a ‘teacher-learner cycle’ to emerge, in which the interviewer takes the learner role exploring with the stakeholder their key assumptions, as teacher [34, 39].

A search through local servers and government databases led to 13 relevant service documents describing the historical context, rationale for service deliverance, role descriptions and desirable policy outcomes. These documents were supplemented with what stakeholders found relevant to the service's implementation and practice (Table 2).

| No | Title (translated into English): | Author/Year | Document type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Practitioners Handbook | Myran L, Johnsen IB, Årøen Lie JP 2019 | Handbook | This handbook provides details on how practitioners should meet and work with the contextual patient group. Details regarding the aetiology of anxiety, symptoms of dental phobia, cognitive behavioural therapy and ways of communicating to enhance relationship-building are elaborated. |

| 2 | Practitioners Guidance | 2018 | Guidelines on the operating practice | This guidance leaflet describes some potential service routes for the patient, resources (such as templates for anxiety treatment), inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients and overall aspects to consider for practitioners (such as collegial support and collaborating with others). |

| 3 | Treatment contract and TADA info | N/A | Service aid | The treatment contract supports joint relationships and collaborative work to restore the patient's oral health. |

| 4 | Treatment plan | N/A | Service aid | The treatment plan is a template and a plan for each session and describes small and large goals for the patient to achieve throughout the service pathway. |

| 5 | Coping plan | N/A | Service aid | This coping plan is jointly filled out by the patient and the TADA dental practitioner. The coping plan aims to aid in the dental restoration phase – making the patient and the follow-up dental practitioner aware of their triggers, stop signs and needs for adjustment. |

| 6 | Patient handbook | 2019 | Guidebook | Patients receive a handbook describing the aim and outline of the service. The handbook includes details on anxiety and traumas and their effects on the dental setting. |

| 7 | White paper 35: accessibility, expertise and social equality for the future's dental health service | 2006–2007 | Policy paper | Describes the government's objective to create and offer equal health care services – regardless of diagnosis, place of residence, personal finances, gender, ethnic background and the individual's life situation. |

| 8 | Facilitated dental health services for people who have been subjected to torture, abuse or odontophobia | The Norwegian Directorate of Health, October 2010 | Report | The first report developed before TADA teams were established. This report describes the different aspects of the patients and offers a rationale for why they need facilitated dental treatment or therapy. |

| 9 |

Job description Dentist/Dental Hygienist |

N/A | Role description | The job description describes the expected tasks the dental practitioner should execute. |

| 10 | Job description Dental Assistant | N/A | Role description | The job description describes the expected tasks the dental assistant should execute. |

| 11 | Job description Psychologist | N/A | Role description | The job description describes the expected tasks the psychologist should execute. |

| 12 | TADA survey | N/A | Survey | This is a survey conducted by a private dentist (not a TADA service practitioner), collecting thoughts from other (mostly private) practitioners regarding the service. Thirty statements are reported – all expressing negative concerns about the workings of the service. |

| 13 | Overall reporting on the TADA service | The Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 | Report | Yearly reporting revealing data on the types of patients enrolled in the service, waiting lists, total number of TADA teams within each county and the service's economic aspects. |

To ensure the trustworthiness of the data collection procedures, the first author immersed herself in the TADA field by tracking dental practitioners in meetings, experiencing exposure therapy sessions, and practising reflexivity by journaling. The Norwegian National Centre of Research Data approved this project (Project No: 619754).

Analyses and data management

Context-mechanism-outcome configurations are the unit of analysis in realist evaluations and serve to help develop programme theories. A standard procedure in realist evaluations is to use the data iteratively, allowing the researcher to unpack the context-mechanism-outcome elements and refine and continue to develop the programme theory [35, 42]. The procedures are thus neither deductive nor inductive. Instead, they are abductive with a retroductive approach – continually asking why and how service outcomes arise and gaining new insights accordingly [43, 44]. We first followed a direct content analysis approach described by Hsieh and Shannon [45], followed by a re-examination of the analysis using the context-mechanism-outcome heuristic as an analytical framework [34]. Data from the interviews and documents were analysed with the support of the qualitative software program NVivo [46].

Each context-mechanism-outcome configuration is depicted in separate tables below and are directly drawn from the analyses (Tables 3–5). The context-mechanism-outcome configurations function as building blocks for developing and refining the programme theories. Quotes are anonymous, although non-identifying data on the interviewee's professional background is added to enhance credibility [45]. The quotes have been translated from Norwegian into English by the first author, then back-translated from English to Norwegian by an independent party to ensure their meaning holds up under translation.

| Context + | Resource → | Reasoning = | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMOC 1 | The institutional context does not place pressure on the dental practitioners and is considerate regarding this patients’ anxiety levels hindering a speedy process, and the time it may take for patients to build trust towards the dental practitioners. | By providing the resource of time | Time allows the dental practitioners the space to engage in active listening, display patience and flexibility |

Immediate outcome: with trust in place, the dentist can commence exposure therapy. Service outcome: the dental practitioner alleviates the patient's dental anxiety, who is then ready for dental restoration. |

| Juxtaposed CMOC 1 | The institutional context reflect time as a tool to measure performance and place pressure on the dental practitioners. | Time is not provided as a resource; instead, it is used as a tool to measure work performance | Then the dental practitioner will feel rushed, and will not have time to establish a trusting relationship with the patient |

Immediate outcome: the patient experiences an anxiety response. Service outcome: a lower likelihood of the patient finishing the exposure therapy |

| Context + | Resource → | Reasoning = | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMOC 2 | The context mirrors an institutional setting and interpersonal relationship between psychologists and dental practitioners, supporting the knowledge transfer and collaboration between psychologists and dental practitioners through service resources and placing them within proximity. | Resource required is a close collaboration between dentist and psychologist, so dentists learn strategies for communicating and displaying sensitivity. Additional supplements are tangible resources (such as pamphlets) that provide examples of how to communicate with different patients and of how desensitisation within exposure treatment works. | With these resources, it is believed that the dental practitioner facilitates a safe space. A safe space reflects sensitivity, predictability, and control. |

Immediate outcome: the dental practitioner can effectively introduce and provoke the patient with the fear-provoking stimuli. Service outcome: alleviated dental anxiety. |

| Juxtaposed CMOC 2 | The contexts lack interpersonal relationships between key actors; thus, the dental practitioner has not learnt how to display sensitivity or match their communication level with the patient. | Dental practitioners are not collaborating with the psychologist, and there is a lack of tangible resources explaining to the dentist different ways to communicate. | The dental practitioner thus cannot facilitate a safe space; the patient will perceive the exposure therapy as threatening. |

Immediate outcome: anxiety responses are activated in the patient and the dental practitioner will be unable to commence exposure therapy. Service outcome: the dental practitioner will not be able to alleviate the patient's dental anxiety. |

| Context + | Resource → | Reasoning = | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMOC 3 | The institutional setting reflects a supportive environment and a good ethos for learning the additional skills needed for the psychological intervention. Also, the interpersonal relationship between psychologists and dental practitioners is accommodating and welcoming, allowing dental practitioners to build a repertoire on how to grade the pace of exposure to bespeak the individual's need. | Resources that allow dental practitioners to regulate the pace of exposure involve courses where they discuss challenges and procedures with psychologists; secondments to other clinics and oral health centres, focusing on dental anxiety; and experience. These resources provide a repertoire of how to regulate pace during the exposure. | If the dental practitioner can speed up or slow down the exposure, they become confident in their role as a therapist and match the pace of exposure to patients’ tolerance levels. |

Immediate outcome: the dental practitioner delivers the exposure therapy, which matches the patient's tolerance level. In cases where the patient is challenged outside of their tolerance window, the dental practitioner can bring them back to a tolerable level. Service outcome: alleviated anxiety. |

| Juxtaposed CMOC 3 | The context is affected by performance-led measures, which hinders dental practitioners to develop interpersonal skills. | There is a lack of resources that support skill development in dental practitioners in exposure therapy and no development programmes, secondments or training. | Dental practitioners are unable to match the pace of exposure therapy to the needs of the patient. |

Immediate outcome: The pace of exposure therapy does not match the patient's therapeutic window. Service outcome: drop out, or no change in anxiety responses. |

RESULTS

Our analyses from the service deliverers’ perspective led to three context-mechanism-outcome configurations describing dental practitioners' role change, from one with focusing only on oral pathologies to one including treatment of dental anxiety. These have been juxtaposed, revealing the contrast between contexts [47]. Overall, our findings describe how dental practitioners need time and support institutionally to match their communication needs and grade the exposure therapy, reducing the patients' dental anxiety.

Programme Theory One: Time leads to trust

The first context-mechanism-outcomeconfiguration is that time with the patient leads to a trusting relationship between the dental practitioner and patient, allowing exposure therapy to commence (Table 3).

Stakeholders from a dental background reflect on dentistry being a traditionally performance led practice. Services are often measured in terms of completing as many patients as possible in as little time as possible. Whereas regular dental practitioners are used to restoring multiple teeth within a couple of hours, dental practitioners in the TADA service report spending up to several hours just ‘getting the patient into the dental chair.’

Stakeholders in the interviews believed that a patient's experience of trauma or suffering from dental phobia reduced their ability to trust the dentist. To establish trust, dental practitioners needed to give patients time to understand that neither the exposure therapy, nor the dental practitioner, would harm them. By introducing time as a resource into the institutional context, dental practitioners have the space to practice active listening, display patience and be flexible – allowing trust to emerge.

Your job, using behavioural therapy, becomes so much easier if you have a good relationship because then it's so much easier to get the patients to step into it … If you have established a base relationship … where the patients feel that: ‘okay, I trust her if she says this will be okay – then I can try’. Then we are so much faster at work. I think the relationship is super important. (Dental practitioner)

You have those patients where relational problems [are] at the core. They might have been subjected to abuse or violence or … have a lot of chaos and clutter and fail to care for themselves … [They have] basic trust issues really … confidence issues … They don't have anyone around them to trust. (Psychologist)

[It] takes a very long time before they trust that the dentist really wishes them well. And then we sort of have to start a slow adjustment, … we constantly need to check that they are with us and that they are not dissociating or just struggling their way through it. (Psychologist).

Programme Theory Two: Matching communication styles

The second context-mechanism-outcome configuration is that matching their communication style to that of the patient, allows the dental practitioner to develop a safe space.

Stakeholder interviews and service documents describe how TADA patients' level of comprehension – when it comes to their understanding of their dental fear responses and treatment procedures – varies greatly. Some patients will require a thorough description of the drill: what it does, why and how, while others may not. Patients also vary in their need to discuss their reactions before exposure. Exposure therapy is a branch within CBT, and patients learning about the tools and procedures used in dental treatment is part of this treatment process. Service documents outlining treatment procedures note that the patient's comprehension of the process is an essential step (Table 4).

The stakeholders interviewed noted that the dental practitioners must display sensitivity and match their communication style to that preferred by the patient and ensure that the patient has comprehended the exposure procedures involved. By being sensitive to the patient, the dental practitioner can pick up on the individual patient's needs and reactions to the information. Stakeholders with a psychological background describe this sensitivity as normative within psychological interventions. They believed that close collaboration with the psychologist could allow dental practitioners to cultivate this sensitivity. Stakeholders with a background in dentistry suggest that this collaboration be supplemented with other tangible resources (e.g., pamphlets), which can be provided to patients. These documents should describe the steps to be taken in the treatment, how each exposure session affects a patient's anxiety levels, and how to cope with this (Table 4).

Some [patients] are razor-sharp, incredibly resourceful. [They] take this cognitive behavioural therapy with a straight-arm. … I can't talk to them in the same way as someone who is resource-poor and has a lot of anxiety problems, and little schooling and don't, don't understand the rationale behind what we do … and it's so exciting that we have to adapt it like that! (Dental Practitioner)

‘Why do you use a drill like that, and why do you use it, why does it make such a sound, why does it feel like that on the tooth’ – yes … lots of things people don't know and, therefore, have made up some explanation for this. Then it is important to remember that it is likely that TADA patients will have had experiences that have made them scared. They have avoided [dental examinations] for many years, and only sought care for acute cases, when it is a complete crisis with inflammation and caries to the pulp … and in those cases, they haven't experienced a ‘normal" dental treatment’. (Dental Practitioner)

Programme Theory Three: A graded pace facilitates gradual and successful exposure

The third context-mechanism-outcome configuration is that if a dental practitioner takes a graded pace to therapy, this facilitates a gradual and successful exposure to dental care.

Stakeholder interviews and service documents describe the high degree of anxiety the patients experience when under care. This is a consequence of suffering from a dental phobia or traumas and inhibits their ability to accept treatment procedures. Stakeholders from dental backgrounds explain how patients may dissociate or experience a panic attack while being exposed to the drill. The service document (no. 2, Table 2) describes patient dissociation as a survival instinct, an anxiety response where patients mentally detach themselves from the current dental experience and their immediate surroundings to deal with the feeling of pain. Stakeholder interviews, however, describe these anxiety responses as severe and unwanted as they are exhausting for both the patient and the dental practitioner. To avoid these severe anxiety responses, dental practitioners must regulate the pace of the exposure to match patients' tolerance levels. By regulating the pace to match patients' tolerance levels, patients can manage their responses while being gradually challenged by increasing levels of exposure. This leads to gradual desensitisation, habituation to, and acceptance of, the feared stimuli (Table 5).

The stakeholders interviewed described the dental practitioners' ability to regulate the pace of treatment as one of the critical resources required in the service. They regulate it by working within the 'therapeutic window'. The 'therapeutic window', referred to in service documents and by stakeholders, is a term widely used within anxiety treatment to describe the degree of arousal in the patient's nervous system that is tolerable for them and allows them to receive the exposure therapy efficiently. The stakeholders explain that if the pace is too fast, the patient goes out of this therapeutic window and 'you lose them'. Once outside their window of tolerance, the patient is driven to one of four biological reactions to the perceived danger: fight, flight, freeze, or faint. None of these responses is desirable.

Nevertheless, learning how to regulate the pace of treatment so that it matches the patient's therapeutic window is not something dental practitioners learn in dental school. Thus, the TADA service offers courses for dental practitioners to learn the skillset of providing and adjusting the pace to match the patient's tolerance. Stakeholders with dentistry backgrounds also described learning by doing or through experience. They noted that such experience taught dental practitioners to practice vigilance, tune in to patient reactions, and adjust the pace accordingly.

…those [patients] exposed to abuse, and especially those with a severe abuse experience,… very easily just sort of zoom out. They just opt-out. They roll down the curtains, and then they just persevere.… You can't just continue with the exposure therapy, because they won't get it. Then, it is so much more to work on: work on being present, work on being able to withstand something happening …. You can't run it [the exposure treatment] in the same way for someone who easily dissociates, as with someone who is completely cognitive, capable and realises that this is just anxiety. (Dental Practitioner)

When we are in the tolerance window, we can think clearly and learn new things. Then we are aware of our feelings and endure them quite well. We may feel both stressed, angry and sorry, but not in a way that activates our survival reactions. (No. 2, Table 2).

DISCUSSION

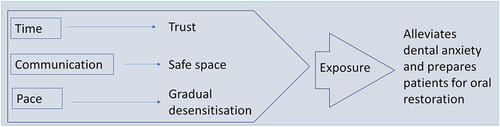

Our initial program theory described an assumption in the TADA service that the patients suffering dental phobia or trauma can have their anxiety alleviated through exposure therapy [38]. Despite the advantages of employing dental practitioners in exposure therapy [2], this requires a role change. Our findings revealed that dental practitioners must deviate from detecting and treating oral pathologies to attending to psychological needs. How, and in what circumstances, dental practitioners can adopt this role change is summarised in Figure 1.

Our analyses (Figure 1) revealed first that, for dental practitioners to adopt this role change, the institutional context must facilitate practitioners' having ample time for their consultations with the patient. Participants also believed that dental practitioners needed to develop their individual capacity to match patients' communication styles and adapt the pace of exposure therapy to the particular needs of the individual patient. In sum, the dental practitioners asserted that this fostered trust, a safe space, and gradual exposure are required to address the particular individual needs of the TADA service patients.

Skaret and Soevdsnes [48] explain that trust between practitioner and patient is essential to commence therapy and to receive its benefits from a therapeutic perspective. Fostering a trusting relationship between dental practitioners and patients is supported in studies exploring what trauma survivors or patients with high dental anxiety require from dental practitioners [12, 31, 48]. Our study shows this to be particularly the case for patients with a high degree of dental fear for whom facilitating trust and reflecting an atmosphere of patience affects their perception of the dental encounter and positive rating of the service. However, as previously noted, time is traditionally described as a performance measurement within the dental context (e.g., a target number of patients treated per week). Such performance-led measures for cost-effective procedures are typical in New Public Management and the pay for performance system, and some view them as attractive within dentistry also [49-51]. However, we argue that the services for patients with trauma and phobia, such as TADA, should provide extra time as a resource for attending to patients’ psychological needs. This suggests that a performance-led environment, where there is a focus on getting target numbers of patients treated per set time period, can prevent dental practitioners from delivering effective exposure therapy. On the contrary, if more time per patient is provided as a resource for dental practitioners to display patience, practice flexibility and actively listen to patients' needs, our participants believed this would foster trust between them and the patient.

Parallel to cultivating trust between patient and dental practitioner, our second programme theory describes facilitating a safe space as fundamental for successfully alleviating dental anxiety. This is a space in which the dental practitioner has created a predictable environment that allows the patient to gain a stronger sense of control. A previous study investigating dentistry consultation models found that creating predictability and establishing a safe space affected the therapeutic alliance, which likely positively influences practitioner–patient collaboration and interaction [52]. A safe space is also considered essential to facilitating dental attendance for abuse survivors and children with dental anxiety [12, 53]. Building on this knowledge – demonstrated in numerous studies – of how essential it is to create a safe space, the realist evaluation approach has allowed us to unpack which resources enable TADA dental practitioners to facilitate this safe space. As seen in our second programme theory, a dental practitioner facilitates a safe space by matching their communication style with the patient's comprehension levels and displaying sensitivity. Dental practitioners learn how to communicate and display sensitivity through close collaboration with a psychologist and by applying tangible resources (e.g., pamphlets explaining exposure procedures). This means the setting in which the service is implemented needs to be supportive of resources (such as pamphlets) and promote an interpersonal relationship between the psychologist and dental practitioner, allowing these new skills to develop. Their skills of displaying sensitivity and adapting a communication style require dental practitioners to embrace what Rosing et al. [54] describe as a `change of focus from the clinical to the relational’.

Our last programme theory describes how dental practitioners facilitate gradual exposure for TADA patients. Exposure therapy works on the assumption that, with a direct and active approach, the patients will develop new responses to the feared stimuli and will learn that their catastrophic thoughts were just that: thoughts [7]. A drill is a tool that may trigger an anxiety response due to its appearance, sound, and sensation [16]. A catastrophic thought related to the drill, for instance, could be that it will drill a hole through the entire tooth. Challenging this thought, operationally, means that the patient may permit the dental practitioner to place the drill in the patient's mouth for 10 s in the first session. This time of exposure may then be slowly increased, in subsequent sessions.

However, it is vital that a patient's tolerance is not tested so much that they are lost outside their therapeutic tolerance window, where they cannot mentally return to the session. This places potential pressure on the dental practitioner performing the exposure task because they must regulate the pace of the exposure correctly, matching this to each patient's particular needs and allowing for a gradual desensitisation process to occur. However, if the pace of exposure did not match patients' needs and dental practitioners did 'lose' the patients, psychologists, with whom dental practitioners had formed close interpersonal relationships, were close at hand. As noted, the term ‘therapeutic window’ is borrowed from anxiety treatment and refers to arousal level. It is the gap between a state of under- and over-arousal that interferes with an efficient delivery of therapy [55]. For dental practitioners to adopt and work within this window, we argue that there is a need for training and education beyond what dental schools currently teach. Norwegian dental schools currently offer a few behavioural subjects as electives. Yet, as our third programme theory reflects, additional resources to evaluate the challenges of exposure activities, and acquire explicit knowledge of how to work collaboratively and interprofessionally with psychologists, are needed. When reflecting on their experience of regulating exposure, our stakeholders often portrayed this as tacit knowledge, which allowed them to tune into the patient [56]. This tacit knowledge was acquired through ‘learning by doing' and with the support of an attending psychologist [57]. Training that involves the growth and transfer of explicit knowledge in this area would supplement dental practitioners' tacit knowledge (experience). Harnessing both knowledge types is valuable for dental practitioners to regulate patients' exposure pace correctly.

Although we have provided new insight into a role change required by dental practitioners, our study has some limitations. The findings provided by this study are drawn from informants who participated in both developing and delivering TADA. It is conceivable that, naturally, their perspectives may be biased and present an overly positive view of the success of the service. Further, when interviews are guided by theories, stakeholders may try to agree with and to please the interviewer, providing socially desirable information that either satisfies societal norms on the treatment of vulnerable groups or alternatively complies with any research hypothesis the researcher brings tentatively to the interview for testing [45]. Questions raised in the interviews also required stakeholders to recall events, and this recall of past events may be flawed. Measures aimed at overcoming these biases were to collect data from multiple sources (documents and interviews), with multiple stakeholders from various background (psychology and dentistry) providing an interdisciplinary perspective. We also focussed the interviews on the processes at play and underplayed the fact that the study was an evaluation of the service in a traditional sense. It was emphasised that this study centred on refining an initial programme theory on how the services works and for whom [34]. Finally, the interviewer kept a reflexive journal, auditing the process and decision making, and examining any biases that may have arisen during the data collection [45, 58]. Finally, the theories of the service developers/deliverers expressed here now require further testing with other stakeholder groups, including patients' perspectives, which is part of an ongoing phase of the current realist evaluation cycle of which this study was part.

In conclusion, our thick descriptions, building on qualitative data and a realist methodology, have allowed us to explore how – and under which circumstances – dental practitioners manage a new role of alleviating dental anxiety for patients with a history of trauma or dental phobia. In examining the dentist's new role in such a service in the Norwegian context (TADA), we find that practitioners believe their role is to build trust and a safe space for their patients and be setting an appropriate pace for their gradual desensitisation. To achieve this, dental practitioners require the specific resources of time, communication skills/tools to achieve this. Dentistry is, however a profession that focuses on the technicalities of restoring oral pathologies rather than on assessing and treating psychological needs. For dental practitioners to deliver exposure therapy, they are required to work outside their traditional professional domain. It is thus suggested that dentists be better supported to expand their professional domain. Policymakers should consider increasing the psychological content and the interprofessional nature of both dental training and the daily work of practitioners interacting with patients with trauma or dental phobia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the informants for taking the time to participate in this study.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Oral Health Centre of Expertise Rogaland, Norway, encompasses a TADA team.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualisation: Emilie Bryne, Sarah Hean, Kjersti Evensen, Vibeke Bull; Methodology: Emilie Bryne, Sarah Hean; Validation: Emilie Bryne, Kjersti Evensen; Formal Analysis and Investigation: Emilie Bryne; Data Curation: Emilie Bryne, Sarah Hean, Kjersti Evensen, Vibeke Bull; Writing – Original Draft: Emilie Bryne. Writing – Review and Editing: Emilie Bryne, Sarah Hean, Kjersti Evensen, Vibeke Bull; Visualisation: Emilie Bryne; Supervision: Sarah Hean, Kjersti Evensen, Vibeke Bull.