Differential effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on patients presenting to a neurological emergency room depending on their triage score in an area with low COVID-19 incidence

Abstract

Background

We analyzed the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on neurologic emergencies, depending on the patients' triage score in a setting with relatively few COVID-19 cases and without lack of resources.

Methods

Consecutive patients of a tertiary care center with a dedicated neurologic emergency room (nER) were analyzed. The time period of the first lockdown in Germany (calendar weeks 12–17, 2020) was retrospectively compared to the corresponding period in 2019 regarding the number of patients presenting to the nER, the number of patients with specific triage scores (Heidelberg Neurological Triage Score), the number of patients with stroke, and the quality of stroke care.

Results

A total of 4330 patients were included. Fewer patients presented themselves in 2020 compared to 2019 (median [interquartile range] per week: 134 [118–143] vs. 187 [182–192]; p = 0.015). The median numbers of patients per week with triage 1 (emergent) and 4 (non-urgent) were comparable (51 [43–58] vs. 59 [54–62]; p = 0.132, and 10 [4–16] vs. 16 [7–18]; p = 0.310, respectively).The median number of patients per week declined in categories 2 and 3 in 2020 (41 [37–45] vs. 57 [52–61]; p = 0.004, and 28 [23–35] vs. 61 [52–63]; p = 0.002, respectively. No change was observed in the absolute number of strokes (138 in 2019 and 141 in 2020). Quality metrics of stroke revascularization therapies (symptom-to-door time, door-to-needle time or relative number of therapies) and stroke severity remained constant.

Conclusion

During the lockdown period in 2020, the number of patients with emergent symptoms remained constant, while fewer patients with urgent symptoms presented to the nER. This may imply behavioral changes in care-seeking behavior.

INTRODUCTION

Documentation of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic started in December 2019 in China [1]. It rapidly spread all over the world and caused fundamental problems in healthcare supply. At the time of writing (October 2020) over 43 million cases have been counted by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [2]. Due to the fast increase in COVID-19 patients in Italy and the rapid spreading of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in Europe, the German government implemented strict regulations for social distancing, starting around calendar week 12. While the number of COVID-19 cases in Germany remained relatively low (less than 200,000 until July 2020), the effects on the healthcare system and changes in care-seeking behavior began to evolve nonetheless. Similarly to other countries, a reduction in patients presenting with symptoms suspicious of ischemic stroke was reported in many regions of Germany [3-5]. Moreover, a decrease in emergencies unrelated to COVID-19 has been found [6]. Ramshorn-Zimmer et al. [6] found that there were also fewer ambulances coming to an interdisciplinary emergency room (−14%), and fewer patients with less urgent triage scores presented themselves. While dyspnea was a more frequent presentation, neurologic emergencies seemed to become less frequent. Another study of 36 emergency rooms in Germany showed similar results [7]. A reduction of 38% in the number of patients with emergencies (neurologic and non-neurologic) was seen in comparison to the previous year. Furthermore, they found a reduction independent of age, triage score, sex, and trauma or non-trauma patients. The relative reduction in stroke patients was approximately 24%. Even more troubling were reports that, in addition to patients requiring emergency assistance not presenting themselves in the emergency rooms, the quality of emergency care decreased, leading to increased door-to-therapy times [8], or door-to-computed tomography (CT) times [9] and reduced rates of intravenous thrombolysis [10].

We set out to find more detailed information on patients presenting to a dedicated neurologic emergency room (nER) who were triaged using a validated neurologic triage system [11]. Considering that stroke is the most prominent and most urgent neurologic emergency, we also wanted to study care-seeking behavior in patients with symptoms suspicious for stroke and the quality time of stroke care during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In order to study the effects of the pandemic that were not caused by lack of resources, we studied a region with a relatively low number of COVID-19 cases in calendar weeks 6 to 17 in 2020, focusing on the psychological effects of the pandemic. This seemed especially important as, in contrast to the lack of resources during a pandemic, psychological effects or awareness for urgency can be more easily countered, for example, by information campaigns, as has been shown recently with the Swedish National Stroke campaign [12].

In detail, we addressed four questions: 1) Was there a decrease in patients presenting to the nER? 2) If yes, did it affect patients of all triage categories? 3) Did care-seeking behavior change in patients with suspected stroke? 4) Was the quality of ischemic stroke care reduced?

METHODS

Patients and variables

This was a retrospective cohort study performed at a tertiary care hospital with a comprehensive stroke center and a dedicated nER. The city of Heidelberg has approximately 160,000 inhabitants (https://www.heidelberg.de/hd/HD/Rathaus/Heidelberg+in+Zahlen.html) and lies in the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. Its university hospital is one of the few comprehensive stroke units in the region, receiving referrals from a broad region, which is why COVID-19 numbers of the surrounding Rhine-Neckar-district were also analyzed.

We collected data on the HEINTS triage [11] of all consecutive patients during calendar weeks 6 to 17 of 2019 and 2020. Briefly, HEINTS is the abbreviation for Heidelberg Neurological Triage System and consists of four categories. Category 1 patients need to be seen immediately, category 2 within 2 h, category 3 should be seen on the same day and category 4 are patients who are not considered to be an emergency. Further details on HEINTS and its validation can be found in previously published studies [11]. Triage scores were given by trained emergency nurses and validated by a consultant neurologist with extensive experience in difficult cases. We defined the time period from calendar weeks 6 to 11 as before the lockdown and weeks 12 to 17 as during the lockdown. The lockdown comprised a number of measures, for example, restriction of social contact, closure of schools and kindergartens, closure of hotels and restaurants, and prohibition of cultural activities. In addition to the overall number of patients in the nER, we collected data on patients who presented to the nER with suspected stroke. TIA was included if such patients were still symptomatic on arrival at the nER. From patients with suspected stroke, age, sex, symptom-onset-to-door time, door-to-needle time, premorbid modified Rankin scale score, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, hypercholesterinemia, current smoker, atrial fibrillation, previous stroke), National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, admission modality (ambulance, referral from another hospital, self-presentation or referral from general practitioner) and percentage of patients treated with recanalization therapy (intravenous thrombolysis and/or mechanical thrombectomy) were recorded. Minor stroke was defined as NIHSS score ≤3 [13] and was analyzed because we speculated that these patients would be the most likely to delay presentation to the nER during the lockdown. We chose symptom-to-door time as the main criterion for how quickly patients and relatives reacted to known stroke-suspicious symptoms. Using last-seen-well times would have distorted the results, even though these are more relevant for therapeutic decisions.

Numbers of patients with COVID-19 were downloaded from the state public health department (https://www.gesundheitsamt-bw.de/lga/DE/Seiten/default.aspx).

Statistics

The primary analysis comprised the median number of patients presenting themselves to the nER per week during the lockdown in 2020 compared to the corresponding period in 2019. Key secondary analyses were the distribution of triage scores, the total number of strokes, symptom-to-door time and door-to-needle time during these periods. Descriptive analysis was performed using number of patients and percentage, and median and interquartile range (IQR) for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariable analysis was performed using Fisher's exact and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Fisher's exact test was used when the number of one field was below 5. For continuous variables, the Mann–Whitney U-test was performed. For multivariable analysis, binary logistic regression analysis was used. The alpha-level was set to 0.05, and all reported p values are two-sided.

Ethical approval and patient consent

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (statement S-302/2020). The requirement for informed consent was waived, as the study was retrospective and only data from clinical routine were used for this study.

RESULTS

Triage score

In total, 4,330 patients with triage scores were included in 2019 (2372) and 2020 (1958). The total number of patients presenting to the neurologic emergency room in 2020 during the lockdown was 777, compared to 1,119 patients in 2019. A total of 1,181 patients were treated in 2020 before the lockdown (calendar weeks 6–11).

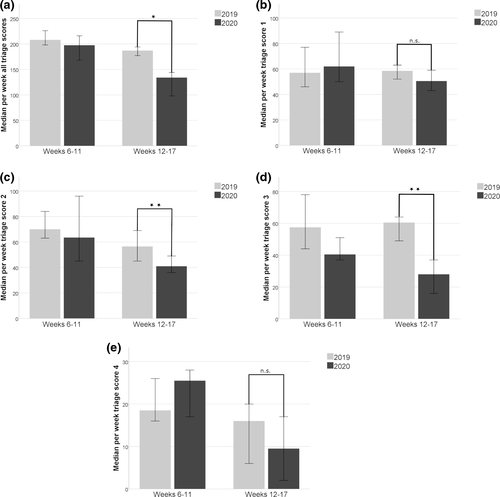

The median (IQR) number of patients admitted per week was significantly lower during the lockdown 2020 (134 [118–143]) compared to the same time period in 2019 (187 [182–192]; p = 0.015). Effects on the median number of patients differed according to the triage category. While there was no significant difference in triage categories 1 and 4 comparing the lockdown period 2020 with 2019 (51 [43–58] vs. 59 [54–62]; p = 0.132, and 10 [4–16] vs. 16 [7–18]; p = 0.310, respectively) the median number of patients per week was significantly lower in categories 2 and 3 (41 [37–45] vs. 57 [52–61]; p = 0.004, and 28 [23–35] vs. 61 [52–63]; p = 0.002, respectively [Table 1 and Figure 1]). In terms of neurologic diagnoses, the main decrease in these triage categories occurred in autoimmune disorders (−90%, 10 in 2019 vs. 1 in 2020), epilepsy (−39%, 71 in 2019 vs. 43 in 2020) and subacute stroke (−15%, 87 in 2019 and 74 in 2020).

| Weeks 6–11 | Weeks 12–17 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

| Triage 1 | 57 (53–70) | 62 (55–82) | 59 (54–62) | 51 (43–58)# | 57 (53–63) |

| Triage 2 | 70 (66–80) | 64 (47–78) | 57 (52–61) | 41 (37–45)**## | 58 (45–69) |

| Triage 3 | 58 (46–65) | 41 (38–48) | 61 (52–63) | 28 (23–35)**## | 47 (37–49) |

| Triage 4 | 19 (16–24) | 26 (19–28) | 16 (7–18) | 10 (4–16)## | 17 (12–22) |

| All triage scores | 208 (198–218) | 198 (185–213) | 187 (182–192) | 134 (118–143) **## | 191 (150–201) |

- *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively, for the comparison between weeks 12 to 17 in 2020 and weeks 12 to 17 in 2019.

- #p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01, respectively, for the comparison between weeks 12 to 17 in 2020 vs. weeks 6 to 11 in 2020.

The absolute number of COVID-19 cases in the city in which the hospital is located rose from 2 in calendar week 6, to 27 in calendar week 12 and reached 279 in calendar week 17 (Figure 2). Although the University Hospital of Heidelberg was treating patients with COVID-19 at that time, patients were admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine and the Pulmonary Center (Thoraxklinik), which are both located in a different building from the one in which the Department of Neurology is located. At the beginning of the lockdown period, four patients and, towards the end, 24 patients were treated there. No SARS-CoV-2-positive patients were treated in the Department of Neurology during that time. Consequently, no shortage of resources or personnel was observed during this time.

Regarding patients with stroke symptoms upon arrival in the nER, 606 patients were included, 293 in 2019 and 313 in 2020. The median (IQR) age was 74 (63–81), symptom-to-door time was 156 (72–720) and NIHSS score was 3 (1–8). Of these patients, 323 (53%) were male. Most of the patients experienced ischemic stroke or TIA (86%). More baseline variables can be found in Table 2.

| Weeks 6–11 | Weeks 12–17 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

| Number of patients | 155 | 172 | 138 | 141 | 606 |

| Age, years | 74 (62–81) | 73 (61–81) | 75 (64–82) | 74 (63–83) | 74 (63–81) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 69 | 94 | 77 | 83 | 323 (53) |

| Symptom-to-door time, min | 128 (70–421) | 182 (76–722) | 151 (70–731) | 202 (72–1083) | 156 (72–720) |

| NIHSS score | 3 (1–8) | 2 (1–6) | 4 (1–11) | 3 (1–9) | 3 (1–9) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 112 | 137 | 113 | 104 | 466 (77) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 | 48 | 42 | 31 | 143 (24) |

| Coronary heart disease | 41 | 40 | 41 | 33 | 155 (26) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 9 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 38 (6) |

| Hypercholesterinemia | 61 | 71 | 62 | 56 | 250 (41) |

| Current smoker | 29 | 30 | 34 | 35 | 128 (21) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 30 | 37 | 40 | 28 | 135 (22) |

| Previous stroke | 28 | 46 | 31 | 31 | 136 (22) |

| Premorbid Rankin scale score (n = 892), n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 60 | 54 | 45 | 41 | 200 (33) |

| 1 | 49 | 67 | 44 | 51 | 211 (35) |

| 2 | 20 | 23 | 31 | 29 | 103 (17) |

| 3 | 23 | 22 | 14 | 12 | 83 (8) |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 34 (3) |

| 5 | – | 1 | – | – | 2 (2) |

Note

- None of the variables showed a statistically significant difference in the comparison between weeks 12 to 17 in 2020 and weeks 12 to 17 in 2019, or in the comparison between weeks 12 to 17 in 2020 and weeks 6 to 11 in 2020.

- Data are median (interquartile range), unless otherwise specified.

Regarding the total number of stroke patients admitted to the nER before and during (172 vs 141) the lockdown in 2020, there was no significant difference compared to the corresponding weeks in 2019 (155 vs 138; p = 0.613). Moreover, there was no difference in age (74[63–83] vs. 75 [63–82]; p = 0.866), symptom-to-door time (202 [72–1083] vs. 151 [70–731] min; p = 0.310), door-to-needle time (30 [24–59] vs. 37 [26–56]; p = 0.474) and NIHSS (3 [1–9] vs. 4 [1–11]; p = 0.831). All of the patients received cerebral imaging (mostly CT). Similarly, no difference was found in the number of patients undergoing recanalizing therapies (intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy: 23 [19% of all stroke patients] vs. 30 [25%]; p = 0.507). In multivariable analysis adjusting for NIHSS score, symptom-to-door time and age, the year of 2020 versus 2019 was not a significant predictor of whether a recanalizing therapy was used (odds ratio 2.01 [0.96–4.21]; p = 0.064). The mode of admission changed in 2020 compared to 2019. More patients in 2020 were self-presentations or referrals from a general practitioner, while fewer patients arrived with the ambulance (48 (34%) vs. 30 (22%) and 76 (54%) vs. 94 (68%); p = 0.042).

In a subgroup analysis of patients with minor stroke, the symptom-to-door time was not different in 2020 compared to 2019 (285 [101–1195] vs. 216 [78–1195] min; p = 0.505).

As a sensitivity analysis and in order to find out whether our dichotomization at calendar week 12 based on the politically imposed lockdown was correct, we looked at the median number of patients for all triage scores per calendar week. While the decrease in patient numbers already began in calendar week 11, patient numbers stabilized after another drop in calendar week 12 (Figure S1). The statistical analysis comparing calendar weeks 11 to 17 of 2020 with 2019 yielded similar results compared to the initial definition. Significant differences for all triage categories and triage categories 2 and 3 (all p = 0.001), and no difference for triage categories 1 and 4 (p = 0.259 and p = 0.456, respectively) were found.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on patients presenting to an nER in a region with relatively few COVID-19 cases. The overall number of patients presenting to the nER declined in 2020 compared to 2019. While emergencies requiring urgent care (triage score 1) remained unchanged, patients who should be seen within 2 h or on the same day (triage score 2 and 3) declined. Patients who were not considered to be emergencies (triage score 4) presented with a similar frequency before and during the pandemic. Regarding stroke patients we found that the quality of stroke care remained the same. Patients also presented themselves as early as before, measured by the symptom-to-door time, even in patients with minor stroke. The total number of strokes also remained unchanged.

Our finding of a decreasing number of patients presenting to the nER is in line with previously reported studies [6, 7, 14, 15]. A distinctive feature of our study compared to other studies is that the number of COVID-19 cases in our region was relatively low, even compared to other regions in Germany. Therefore, these changes might be attributable to psychological effects. Our study showed that the number of highly urgent patients (triage category 1) stayed the same, which is in contrast to other studies [6, 7], possibly because it was possible to communicate to the general population that emergencies are still being treated despite the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, patients who should be seen within 2 h or on the same day (triage category 2 and 3) did not present as frequently as before to the nER, which shows that more information needs to be distributed regarding urgent but not emergent cases. This is especially important as the number of patients presenting to the nER with disorders such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis or subacute stroke decreased, which could have serious consequences for the patients. While it is relatively easy to explain the difference between emergent diseases and non-urgent diseases to the public, the differentiation between emergent and urgent diseases can be challenging for patients. Several US hospitals and healthcare providers use their homepages to inform patients on symptoms that are considered to be urgent and symptoms that are considered to be emergent (e.g., https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/health-and-wellness-articles/when-to-go-to-the-emergency-room-vs-an-urgent-care-clinic, https://www.gohealthuc.com/UCvsER, https://www.stlukesonline.org/health-services/health-information/health-topics/urgent-vs-emergency-care). It might be beneficial to implement specific information on the treatment of emergencies on hospital websites.

There was no difference in patients who were not considered to be an emergency (triage category 4), suggesting that their personal misjudgment regarding the urgency is severe. Other studies have shown that patients who present themselves in the emergency room with non-urgent diseases tend to overestimate their illness severity [16], which seemed to persist during the first phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Regarding strokes, the quality of acute care was not changed by the pandemic. This was in contrast to studies of regions in which there were many more COVID-19 cases [8, 9, 17], implying that shortage of resources might be a reason for change in quality parameters of stroke care, while other effects such as psychological effects might play a minor role.

Psychological effects could play a role regarding the care-seeking behavior. While some hospitals showed a decrease in stroke patients [4], we did not see a decrease in our population. The possible explanations for this differential effect can only be speculated upon [3]. One reason could be the fact that our hospital has held press conferences encouraging emergency patients to come to the hospital, which could also explain the stable number of patients with a triage score of 1. This is supported by the increased self-presentation in the lockdown period in our study and by the effect on care-seeking behavior by information campaigns [12]. Another aspect that could explain this difference is the high percentage of inhabitants with a college degree in our city (44%). People with higher education show greater adherence to recommendations regarding healthcare [18] and might therefore be able to distinguish better between symptoms that require immediate presentation in an emergency room.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective study that could by design only speculate on the reasons for observed effects and correlations. Secondly, the setting of an nER is specific to certain countries and regions and might not be transferrable to other settings. On the other hand, this allowed us to generate specific results for neurological patients. Thirdly, while most of the patients of the region would have been treated in the hospital, some might have been transferred to other hospitals which are not included in our study. Fourthly, p values were not corrected for multiple testing, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Lastly, while triage is important and HEINTS has been validated, it does not always correspond with the actual urgency of an emergency, which might have led to some distortions in the calculation.

In summary, the present study was able to show specific effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on care-seeking behavior. It emphasizes that these effects are diverse depending on the triage score of the patients. Furthermore, no limitations in the quality of stroke care were observed in an area with a relatively low number of COVID-19 patients. This study encourages communication to the population that they should present themselves with emergencies in the emergency room during a pandemic. In particular, strategies should focus on urgent but not emergent diseases, reassuring patients that they should present themselves to the emergency room. In addition, patients suffering from non-urgent diseases should be informed to prevent unnecessary presentations to the ER which put patients and personnel at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions to the paper were as follows: M. Millan: data curation (lead), formal analysis (equal), project administration (equal), validation (equal), visualization (equal), writing – review and editing (equal); S. Nagel: conceptualization (equal), data curation (equal), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), project administration (equal), validation (equal), writing, review and editing (equal); C. Gumbinger: validation (equal), writing, review and editing (equal); L. Busetto: validation (equal), writing, review and editing (equal); J. Purrucker: validation (equal), writing – review and editing (equal); C. Hametner: validation (equal); writing - review and editing (equal); P. A. Ringleb: validation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal); S. Mundiyanapurath: conceptualization (lead), data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), investigation (lead), methodology (lead), project administration (lead), resources (lead), supervision (lead), validation (lead), visualization (lead), writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All relevant data are published in the manuscript. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.