Subdural hematoma in diabetic patients

Abstract

Background and purpose

Subdural hematoma (SDH) is associated with a high mortality rate. However, the risk of SDH in diabetic patients has not been well studied. The aim of the study was to examine the risk of SDH in incident diabetic patients.

Methods

From a universal insurance claims database of Taiwan, a cohort of 28 045 incident diabetic patients from 2000 to 2005 and a control cohort of 56 090 subjects without diabetes were identified. The incidence and hazard ratio of SDH were measured by the end of 2010.

Results

The mean follow-up years were 7.24 years in the diabetes cohort and 7.44 years in the non-diabetes cohort. The incidence of SDH was 1.57-fold higher in the diabetes cohort than in the non-diabetes cohort (2.04 vs. 1.30 per 1000 person-years), with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.63 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43–1.85]. The stratified data showed that adjusted hazard ratios were 1.51 (95% CI 1.28–1.77) for traumatic SDH and 1.89 (95% CI 1.52–2.36) for non-traumatic SDH. The 30-day mortality rate for those who developed SDH in the diabetes cohort was 8.94%.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that incident diabetic patients are at higher risk of SDH than individuals without diabetes. Proper intervention for diabetic patients is necessary for preventing the devastating disorder.

Introduction

Subdural hematoma (SDH) is the most common severe traumatic brain injury and is associated with a high mortality rate 1, 2. SDH may be of venous or arterial origin 3. Most frequently, the hematoma results from tearing of a bridging vein between the cerebral cortex and a draining venous sinus 4. SDH damages delicate brain tissue by increasing intracranial pressure and shifting brain structures. The clinical manifestation of SDH can be classified into acute, subacute and chronic. Patients with acute SDH often have a major trauma, most commonly caused by motor vehicle crashes in younger patients and by falls in elderly patients 4. In contrast, chronic SDH often occurs in elderly patients after a trivial injury or fall without accompanying injury to the underlying brain 5. Thirty percent to 50% of patients with chronic SDH do not have a history of trauma 6.

Head injury (direct trauma) is an important cause of SDH 7. Other risk factors include fall, old age, reduced cognitive function, use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs, alcohol use, epilepsy, bleeding tendency, low cerebrospinal fluid pressure and renal dialysis 6, 8. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a global serious and growing health problem with high morbidity and mortality 9. DM and aging are known risk factors of falls 10. A recent meta-analysis reports that individuals with DM have 12%–19% increased risk of motor vehicle accident compared with individuals without DM 11. However, no study has investigated whether DM patients are also at higher risk of SDH. This study was to compare the risk of SDH between incident DM patients and non-DM controls using a population-based universal insurance claims database from Taiwan.

Methods

Data sources

The Taiwanese government launched the National Health Insurance program in March 1995, covering approximately 99% of the 23.74 million people by the end of 2009. The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) containing all claim data from 1996 to 2010 for 1 000 000 randomly selected insured people was obtained from the authority for this study. This data set provided information on registry data sets for beneficiaries including all records of outpatient visits and hospitalization, and prescribed drugs. All subjects' identifications for linking files have been scrambled and replaced with surrogate identification numbers to protect privacy. The International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) was used to identify individual health status 12. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University.

Study subjects

After excluding patients with diagnosed diabetes from 1996 to 1999, 28 182 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250.xx) in 2000–2005 were identified from the records of outpatient visits and hospitalizations. Subjects with SDH before the index date (n = 127) and those with incomplete age or sex information (n = 10) were excluded from this study. The remaining 28 045 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes were included in the DM cohort. The diagnosis year of diabetes was designated as the index year for the estimation of follow-up years. For each DM subject, two insured people without a history of diabetes and SDH as the non-DM cohort, frequency matched by age (per 5 years), sex and the index year, were randomly selected.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities potentially associated with SDH were also identified, including coronary artery disease (CAD) (ICD-9-CM code 410−413, 414.01−414.05, 418 and 414.9), congestive heart failure (CHF) (ICD-9-CM code 428, 398.91 and 402.x1), stroke (ICD-9-CM code 430–438), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), atrial fibrillation (AF) (ICD-9-CM code 427.31), hypertension (ICD-9-CM code 401−405), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (ICD-9-CM code 580–589) and dementia (ICD-9-CM code 290.0, 290.1, 290.2, 290.3, 290.4, 294.1 and 331.0).

Primary outcome

Each subject was followed to evaluate the occurrence of SDH, including non-traumatic (ICD-9 code 432.1) and traumatic types (ICD-9-CM codes 852.2–852.3), until 31 December 2010, or was censored because of loss to follow-up, death or withdrawal from the insurance program. Furthermore, 30-day mortality was calculated using death records or withdrawal records in this database.

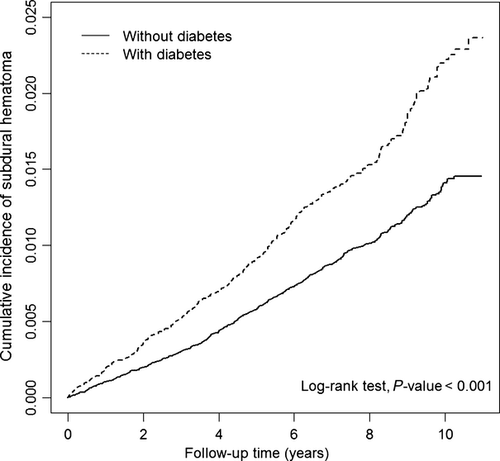

Statistical analysis

Data analysis first estimated the annual age-standardized incidence rate of SDH for the prevalent diabetic patients from 2000 to 2010, based on the Taiwanese population in 1998. Distributions of age, sex and comorbidities were compared between the DM and non-DM cohorts and differences were examined using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and the t test for continuous variables. The Kaplan−Meier estimation method was used to depict the cumulative incidence curves of SDH for the two cohorts and the difference was examined with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) of SDH for the DM cohort compared with the non-DM cohort controlling for the other variables in the model. Moreover, logistic regression analysis was used to measure the odds ratio (OR) of 30-day mortality of SDH in the DM cohort compared with the non-DM cohort. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The two-sided level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Figure 1 shows the annual age-standardized incidence rate of SDH amongst patients with DM from 1998 to 2010, ranging from 2.61 to 3.55 per 1000 person-years (P for trend 0.246). The baseline demographic factors and comorbidities status in the DM cohort and the non-DM cohort are shown in Table 1. The distribution of age and gender were similar in both cohorts. Compared with the non-DM cohort, the DM cohort had higher rates of CAD (13.5% vs. 9.18%), CHF (5.29% vs. 3.36%), stroke (3.83% vs. 2.93%), hyperlipidemia (25.75% vs. 14.70%), AF (1.33% vs. 0.97%), hypertension (30.46% vs. 20.21%) and CKD (8.47% vs. 6.14%).

| Variable | Control N = 56 090 | DM N = 28 045 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 26 200 | 46.71 | 13 100 | 46.71 | 0.99 |

| Male | 29 890 | 53.29 | 14 945 | 53.29 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| <55 | 28 554 | 50.91 | 14 227 | 50.91 | 0.99 |

| 55–64 | 12 402 | 22.11 | 6201 | 22.11 | |

| ≥65 | 15 134 | 26.98 | 7567 | 26.98 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 5148 | 9.18 | 3785 | 13.50 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1883 | 3.36 | 1484 | 5.29 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1643 | 2.93 | 1074 | 3.83 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8246 | 14.70 | 7222 | 25.75 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 544 | 0.97 | 374 | 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 11 333 | 20.21 | 8542 | 30.46 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3442 | 6.14 | 2375 | 8.47 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 506 | 0.902 | 288 | 1.03 | 0.08 |

The mean follow-up years were 7.24 years in the DM cohort and 7.44 years in the non-DM cohort. The cumulative incidence of SDH was 1.0% greater in the DM cohort than in the non-DM cohort (2.4% vs. 1.4%) (Fig. 2) (log-rank test, P < 0.0001). Table 2 presents incidences and HRs of SDH by diabetes status stratified by demographic factor and comorbidity. Overall, the incidence rate of SDH was higher in the DM cohort than in the non-DM cohort (2.04 vs. 1.30 per 1000 person-years), with an adjusted HR of 1.63 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43–1.85]. The incidence of traumatic SDH was higher than that of non-traumatic SDH. The DM cohort had HRs of 1.51 (95% CI 1.28–1.77) for traumatic events and 1.89 (95% CI 1.52–2.36) for non-traumatic events compared with the non-DM cohort. The SDH incidence increased with age and was higher in males than in females. In individuals with comorbidity, DM patients with AF had the highest incidence of SDH with an HR of 5.00 (95% CI 1.78–14.0). For those without any comorbidity, the incidence of SDH was nearly 2-fold higher in DM patients than in non-DM subjects with an HR of 1.93 (95% CI 1.61–2.32).

| Variable | DM | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| Case | Person-years | IR | Case | Person-years | IR | |||

| Overall | 543 | 417348.08 | 1.30 | 414 | 203179.20 | 2.04 | 1.57 (1.38–1.78)*** | 1.63 (1.43–1.85)*** |

| Subtype | ||||||||

| Traumatic | 374 | 417348.08 | 0.90 | 261 | 203179.20 | 1.28 | 1.44 (1.23–1.68)*** | 1.51 (1.28–1.77)*** |

| Non-traumatic | 169 | 417348.08 | 0.40 | 153 | 203179.20 | 0.75 | 1.86 (1.50–2.32)*** | 1.89 (1.52–2.36)*** |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 172 | 198619.72 | 0.87 | 149 | 97214.07 | 1.53 | 1.77 (1.42–2.21)*** | 1.79 (1.44–2.24)*** |

| Male | 371 | 218728.36 | 1.70 | 265 | 105965.13 | 2.50 | 1.48 (1.26–1.73)*** | 1.55 (1.32–1.82)*** |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| <55 | 108 | 222083.40 | 0.49 | 91 | 109330.56 | 0.83 | 1.71 (1.30–2.26)*** | 1.77 (1.33–2.35)*** |

| 55–64 | 120 | 94556.23 | 1.27 | 85 | 46325.31 | 1.83 | 1.45 (1.10–1.91)* | 1.48 (1.12–1.96)* |

| ≥65 | 315 | 100708.45 | 3.13 | 238 | 47523.32 | 5.01 | 1.61 (1.36–1.90)*** | 1.61 (1.36–1.91)*** |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| No | 291 | 273866.83 | 1.06 | 193 | 95023.93 | 2.03 | 1.92 (1.60–2.30)*** | 1.93 (1.61–2.32)*** |

| Yes | 251 | 143481.24 | 1.75 | 221 | 108155.28 | 2.04 | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 1.41 (1.17–1.69)*** |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| CAD | ||||||||

| No | 453 | 383270.15 | 1.18 | 326 | 178198.18 | 1.83 | 1.55 (1.34–1.79)*** | 1.65 (1.43–1.91)*** |

| Yes | 90 | 34077.93 | 2.64 | 88 | 24981.03 | 3.52 | 1.33 (0.99–1.78) | 1.54 (1.15–2.07)** |

| CHF | ||||||||

| No | 505 | 406546.75 | 1.24 | 366 | 194598.37 | 1.88 | 1.52 (1.33–1.74)*** | 1.61 (1.41–1.85)*** |

| Yes | 38 | 10801.33 | 3.52 | 48 | 8580.84 | 5.59 | 1.58 (1.03–2.42)* | 1.74 (1.13–2.67)* |

| Stroke | ||||||||

| No | 501 | 408135.16 | 1.23 | 376 | 197400.53 | 1.90 | 1.56 (1.36–1.78)*** | 1.64 (1.44–1.88)*** |

| Yes | 42 | 9212.92 | 4.56 | 38 | 5778.67 | 6.58 | 1.44 (0.93–2.23) | 1.50 (0.94–2.27) |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||||||

| No | 453 | 357466.99 | 1.27 | 315 | 150432.32 | 2.09 | 1.66 (1.43–1.91)*** | 1.67 (1.44–1.96)*** |

| Yes | 90 | 59881.09 | 1.50 | 99 | 52746.88 | 1.88 | 1.25 (0.94–1.66) | 1.50 (1.13–2.00)* |

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||||||

| No | 538 | 414425.32 | 1.30 | 399 | 201139.35 | 1.98 | 1.53 (1.35–1.74)*** | 1.59 (1.40–1.81)*** |

| Yes | 5 | 2922.76 | 1.71 | 15 | 2039.85 | 7.35 | 4.32 (1.57–11.89)** | 5.00 (1.78–14.00)** |

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| No | 421 | 333622.95 | 1.26 | 312 | 140896.75 | 2.21 | 1.76 (1.52–2.04)*** | 1.75 (1.51–2.03)*** |

| Yes | 122 | 83725.12 | 1.46 | 102 | 62282.44 | 1.64 | 1.13 (0.86–1.46) | 1.32 (1.02–1.73)* |

| CKD | ||||||||

| No | 491 | 394456.95 | 1.24 | 357 | 187521.27 | 1.90 | 1.53 (1.34–1.76)*** | 1.61 (1.40–1.84)*** |

| Yes | 52 | 22891.13 | 2.27 | 57 | 15657.92 | 3.64 | 1.61 (1.10–2.34)* | 1.83 (1.25–2.67)** |

| Dementia | ||||||||

| No | 528 | 414989.88 | 1.27 | 410 | 201922.20 | 2.03 | 1.60 (1.41–1.82)*** | 1.66 (1.46–1.90)*** |

| Yes | 15 | 2358.20 | 6.36 | 4 | 1256.99 | 3.18 | 0.50 (0.17–1.51) | 0.56 (0.18–1.73) |

- DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; IR, incidence rate per 1000 person-years; adjusted HR, mutually adjusted for age, gender, coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and dementia in Cox proportional hazards regression. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

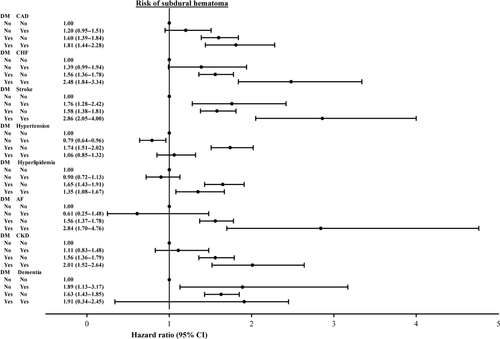

Figure 3 shows the joint effects of diabetes and comorbidities including CAD, CHF, stroke, hyperlipidemia, AF, hypertension, CKD and dementia on the risk of SDH compared with the reference group without DM. In general, the risk of SDH increased further in DM patients with CAD, CHF, stroke, AF and CKD.

The 30-day mortality rate of those who developed SDH was higher in the non-DM cohort than the DM cohort (14.5% vs. 8.94%) (Table 3). The logistic regression analysis showed that the risk of fatality was not significantly lower in the DM cohort.

| n/N (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusteda | ||

| Non-diabetes | 79/543 (14.55) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Diabetes | 37/414 (8.94) | 0.94 (0.63–1.38) | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) |

- a Adjusted odds ratio, adjusted for age, sex, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and dementia.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that DM patients were more likely than non-DM subjects to develop SDH. Although the incidence of SDH was higher for those with trauma than for those without, the relative hazard was greater for those without trauma than for those with trauma (1.89 vs. 1.51). The results might indicate that trauma increases the SDH risk, but the relative impact of diabetes is stronger than that of trauma. No previous studies have reported these findings. DM patients who have not sustained trauma still need preventive measures to reduce the SDH risk.

There may be several reasons for the increased risk of SDH in DM patients. DM individuals are at a higher risk of fall. Fall can lead to traumatic brain injuries and even death 13. Schwartz et al. 14 have found that older diabetic women are associated with an increased risk of fall in a prospective cohort study. The non-insulin-treated diabetic patients had an age-adjusted OR of 1.68 for fall, whilst the risk was even greater for insulin-treated diabetes with an age-adjusted OR of 2.78. They also found that poor balance, a history of CAD, a history of arthritis and peripheral neuropathy might account for some of the increased risk of fall associated with non-insulin-treated diabetes 14. A recent study by Roman de Mettelinge et al. 15 followed old people (104 with diabetes and 95 healthy controls) for a year and reported that diabetic patients had an OR of 2.03 (95% CI 0.49–099) for fall, compared with controls. There are several mechanisms mediating the increased risk of fall in diabetes patients, including frailty, retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, orthostatic hypotension, cerebrovascular accidents, hypoglycemia, urinary incontinence, dementia, reduced cognitive function, depression and poly-pharmacy 15-18.

Diabetic drivers have a slightly increased motor vehicle accident rate 19. The risk may as high as 2.6-fold in old diabetic drivers 20. A systemic analysis also showed that the relative risk of motor vehicle accident increased by 12%–19% 11. Cognitive dysfunction induced by hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia and diabetes complications such as retinopathy and neuropathy contribute to the increased risk of motor vehicle accidents in diabetic patients 19.

Our study demonstrated that the risk of SDH increased further in diabetic patients with CAD, CHF, stroke, AF and CKD. Antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants for high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in diabetic patients and renal failure, the progression of diabetic nephropathy, may further result in bleeding tendency. In addition, brain atrophy is relatively more pronounced in diabetic patients than in individuals without DM 21, 22. Brain atrophy increases the length of bridging veins and this causes stretching of these veins and increases the likelihood of tearing 23.

The present study demonstrated that the age-standardized incidence rate of SDH in prevalent diabetic patients had increased since 2004. The wide availability of modern imaging leads to improvement in diagnosis and may contribute to the increasing rate. Further data analysis showed the trend was not significant.

The strength of the present study includes a large population-based sample size and a matched cohort study model in design. However, there are several limitations. First, information on education level, lifestyle, body mass index, Glasgow coma scale score and laboratory data are unavailable from the claims file. Therefore these variables could not be adjusted in the data analysis. Secondly, because the findings of neuroimaging studies are also not available from this database, it was not possible to classify SDH or to differentiate the prognostic outcomes between patients with acute SDH and those with chronic SDH. Furthermore, SDH and other comorbidities were identified using ICD-9-CM codes. The validity of diagnostic codes for SDH could not be calculated. However, the claims data provided by NHIRD have been evaluated against diagnoses in medical records at a medical center with a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 95% 24. The 30-day mortality using death records or withdrawal records was calculated. Almost all withdrawals from the National Health Insurance program are caused by death 25.

In conclusion, this study shows that diabetic patients are at increased risk of SDH and these SDH cases have a near 9% fatality. Because of the devastating consequences, appropriate prevention is necessary for diabetic patients. Intervention to prevent falls 10, 15, dementia and brain atrophy 21 and avoid hypoglycemic episodes 19, and cautious use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, may have roles in preventing the occurrence of SDH in diabetic patients.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Sciences Council, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (Grant Number NSC 100-2621-M-039-001), China Medical University Hospital (Grant Numbers 1MS1, DMR-101-016 and DMR-103-013) and Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (Grant Number MOHW103-TDU-B-212-113002).

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

Dr Sung receives grants from the National Sciences Council, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, China Medical University Hospital and Taiwan Department of Health Clinical Trial and Research Center for Excellence. The other authors report no disclosures relevant to the paper.