Management Innovation: Management as Fertile Ground for Innovation

Abstract

Innovation is considered to be the primary driving force of progress and prosperity. Consequently, much effort is put in developing new technological knowledge, new process technologies and new products. However, evidence from both SMEs and large firms shows that successful innovation is not just the result of technological innovation, but is also heavily dependent on what has been called ‘management innovation’. Management innovation consists of changing a firm's organizational form, practices and processes in a way that is new to the firm and/or industry, and results in leveraging the firm's technological knowledge base and its performance in terms of innovation, productivity and competitiveness. Recent research shows that management innovation explains a substantial degree of the variance of innovation performance of firms. More active stimulation of management innovation and its leverage of technological innovation will be crucial to improve the competitiveness of firms. However, only solid research can increase our understanding of what matters in various kinds of management innovations. Just as technological change requires systematic R&D, the development and diffusion of management innovations require systematic research on the crucial determinants of success. In this paper we will define management innovation, discuss the multidirectional causalities between technological and management innovation, and develop a framework that identifies common areas of research in terms of antecedents, process dimensions of management innovation, outcomes and contextual factors. Moreover, we will position the papers of this special issue in this framework and develop an agenda for future research into management innovation. We conclude this introductory paper by specifying the most important research priorities for further advancing the emerging field of management innovation.

Introduction

As innovation is considered central to firms' competitive advantage, innovation research has become a cornerstone of strategic management inquiry. By far the greatest part of research has been devoted to understanding how firms can stimulate technological innovation (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010). More recently, however, some researchers have begun to revisit the benefits of management innovation. Management innovation refers to the introduction of management practices, processes and structures that are intended to further organizational goals (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). The emergent dialogue consists of conceptual work (e.g., Birkinshaw et al., 2008), historical outlines of various management innovations (e.g., Chandler, 1962; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2007) and empirical studies (e.g., Damanpour et al., 2009; Vaccaro et al., 2012a, 2012b).

Despite the recent surge in academic interest, management innovation remains an under-researched topic. Crossan and Apaydin's (2010) comprehensive and systematic literature review reveals that generally only 3% of innovation-related papers focus on management innovation. However, as recent work emphasizes the importance of management innovation for firm performance, both as a complement to technological innovation (Damanpour et al., 2009) and as an independent phenomenon (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009; Volberda and Van den Bosch, 2004, 2005), a better understanding of management innovation should be high on the research agenda. For example, Feigenbaum and Feigenbaum (2005: 96) argue that ‘the systematization of management innovations will be a critical success factor for 21st century companies’. Moreover, Mol and Birkinshaw (2009: 1269) state that it is ‘one of the most important and sustainable sources of competitive advantage’ as well as ‘needed to make technological innovation work’ (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2006: 26)

The purpose of this introductory paper is to advance our understanding of management innovation, its underlying dimensions, its antecedents, its impact on performance, and the contextual factors that affect management innovation. We first discuss the old paradigm and the new emerging model of innovation research. Subsequently, we further conceptualize management innovation in order to advance understanding and we develop an integrative framework that can be used to identify where research findings about management innovation converge and where gaps in our understanding exist. Moreover, we point out several emerging research themes that have been under-researched, such as the relationship between technological and management innovation and its differential effects on performance. Finally, we specify the issues for further research derived from our integrative framework, position the papers in this special issue and how they contribute to our research agenda, and select five research priorities that in our view may speed up progress and knowledge advancement in the relatively young field of management innovation.

The old paradigm of industrial innovation under scrutiny

Innovation is considered to be the primary driving force of progress and prosperity, both at the level of the individual firm and of the economy in general (Schumpeter, 1934; Nelson and Winter, 1982; Tushman and Nadler, 1986). In particular, the ability to innovate has become increasingly central as studies have revealed that innovative firms tend to demonstrate higher profitability, greater market value, superior credit ratings, and greater chances of survival (Geroski et al., 1993; Hall, 2000; Czarnitzki and Kraft, 2004). Notwithstanding these positive outcomes of innovation, innovation research itself is subject to creative destruction. The old paradigm of industrial innovation based on technological inventions seems today to be accompanied by many other forms of different types of innovations: organizational innovation (Damanpour et al., 1989; Totterdill et al., 2002), management innovation (Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006; Hamel, 2006), institutional innovation, and, sustainable development and eco-innovation (Kemp et al., 2005). These new areas sometimes fit the old industrial innovation paradigm, but more often they raise new analytical challenges. New ways of carrying out research outside the industrial research laboratory, sometimes in collaboration with others, have started to emerge. Totally new forms of innovation without traditional research are becoming commonplace; ‘open’ innovation is being pursued by some (but not all) firms, involving much greater participation by users (Chesbrough, 2003; Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004; Von Hippel, 2005). Moreover, non-technological innovation, often referred to as management innovation, is playing an increasingly important role in helping us to better understanding innovation and its impact on competitiveness of enterprises and countries. Management innovations can involve changing organizational form, applying new management practices and developing human talent with the effect of leveraging the firm's knowledge base and improving organizational performance (Volberda and Van den Bosch, 2005, Volberda et al., 2006).

The new paradigm of innovation research: various modes of non-technological innovation

What all of this suggests is that innovation as a research topic seems to be particularly prone to new innovative approaches. Hence, there is a need for a better conceptualization of the various notions of innovation. Scholars have produced a vast amount of research that addresses different types of innovation, predominantly technological. In this way, research has centred upon issues such as radical and incremental innovation (Dewar and Dutton, 1986; Ettlie et al., 1984) and product and process innovation (Utterback and Abernathy, 1975). In spite of the undeniable importance of technological innovation, which has been prominent in academic literature and also contributed over the years to – amongst other things – the development of more advanced products, components, and production technology, other types of innovation have successfully been introduced outside the domain of technology.

As firms are faced with increased competition and an accelerating pace of technological change, they need to consider non-technological innovation that is more difficult to replicate (Teece, 2007) and may contribute to a longer lasting competitive advantage. These non-technological forms of innovations have been referred to as administrative innovation, organizational innovation, and management innovation. These concepts have a significant overlap and are used to discriminate from technological process innovations, and from product and service innovations (Damanpour and Aravind, 2011). However, despite their overlap, administrative innovation, organizational innovation, and management innovation are not identical. Administrative innovation has a narrower focus than organizational innovation, for example (Vaccaro, 2010). In comparison with management innovation, administrative innovation is typically associated with a narrower range of innovations around resource allocation, organizational structure and human resource policies (Evan, 1966), and excludes operations and marketing management (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). The concept of management innovation is more encompassing as it refers to alterations in the way the work of management is performed (Hamel, 2006). Furthermore, organizational innovation has often been used in broader terms to span changes that are either technological or administrative (e.g., Daft, 1978; Damanpour, 1991; Kimberly and Evanisko, 1981). In a review, Crossan and Apaydin (2010) define organizational innovation in very broad terms to include the pursuit of any innovative activity within the firm. This definition however does not capture the role of managers as the central actors within organizations or changes to how the work of management is performed (Birkinshaw et al., 2008).

Management innovation research

Whereas technological innovation is concerned with the introduction of changes in technology relating to an organization's main activity (Daft and Becker, 1978), management innovation reflects changes in the way management work is done, involving a departure from traditional processes (i.e., what managers do as part of their jobs); in practices (i.e., the routines that turn ideas into actionable tools); in structure (i.e., the way in which responsibility is allocated); and in techniques (i.e., the procedures used to accomplish a specific task or goal) (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Hamel, 2006, 2007). In relation to this, Birkinshaw and Mol (2006) propose that management innovation tends to emerge through necessity, as opposed to technological innovations that may first be developed in a laboratory and for which an application may subsequently be found. Further, due to its nature, management innovation is likely to constitute a rather diffuse and difficult-to-replicate attribute for any firm who successfully develops one (Birkinshaw and Goddard, 2009). Table 1 provides several definitions of management innovation. Birkinshaw et al. (2008: 829) define management innovation as ‘The generation and implementation of a new management practice, process, structure, or technique that is new to the state of the art and is intended to further organizational goals’. Regarding the novelty of management innovation, ‘new’ can be entirely new to the world or new to the firm (Birkinshaw et al., 2008).

| Authors: | Definition: |

|---|---|

| Mol and Birkinshaw (2009: 1269) | ‘The introduction of management practices that are new to the firm and intended to enhance firm performance’. |

| Birkinshaw et al. (2008: 829) | ‘The generation and implementation of a management practice, process, structure, or technique that is new to the state of the art and is intended to further organizational goals’. |

| Hamel (2006: 4) | ‘A marked departure from traditional management principles, processes and practices or a departure from customary organizational forms that significantly alters the way the work of management is performed’. |

| Kimberly (1981: 86) | ‘… any program, product or technique which represents a significant departure from the state of the art of management at the time it first appears and which affects the nature, location, quality, or quantity of information that is available in the decision-making process’. |

Management innovation covers changes in the ‘how and what’ of what managers do in setting directions, making decisions, coordinating activities and motivating people (Hamel, 2006; Birkinshaw, 2010; Van den Bosch, 2012). These changes reveal themselves by new managerial practices, structures, or processes (Vaccaro, 2010) and they are context-specific (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009), ambiguous and hard to replicate, making them an important source of competitive advantage (Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006; Hamel, 2006; Damanpour and Aravind, 2011). Although a firm may build on the management innovations of other firms, its success is also determined by how those management innovations are adapted to the unique context of the organization (Ansari et al., 2010).

Classic types of management innovation are Ford's moving assembly line (Chandler, 1977) and the multidivisional structure of DuPont and General Motors (Chandler, 1962). More recent types of management innovation include total quality management (TQM) programmes (e.g., Zbaracki, 1998), ISO certifications (e.g., Benner and Tushman, 2002) and self-managed teams (e.g., Hamel, 2011; Vaccaro et al., 2012b). While it is a requirement for innovation, change does not in itself constitute management innovation (West and Farr, 1990). For instance, downsizing may bring about changes to an organization, but cannot be regarded as management innovation if the managerial work itself continues unchanged (Vaccaro, 2010). Genuine management innovation must involve substantial changes in how the organization is managed, reflected in the introduction of new practices, processes, structures and techniques.

Management innovation usually has the purpose of increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of internal organizational processes (e.g., Adams et al., 2006; Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2011). Consequently, management innovation increases the productivity and competiveness of firms (Hamel, 2006) and enables economic growth (Teece, 1980). Nonetheless, developing a management innovation is a complex process (Vaccaro, 2010) and involves internal and external change agents (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). Internal change agents include a firm's managers and employees who are involved in the management innovation. External change agents can be consultants, academics or other external actors who influence the adoption of a management innovation (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Vaccaro, 2010). They initiate and drive the process (Birkinshaw et al., 2008), and the typically intangible, tacit and complex management innovations emerge without a dedicated infrastructure (Vaccaro et al., 2012a).

An integrative framework of management innovation

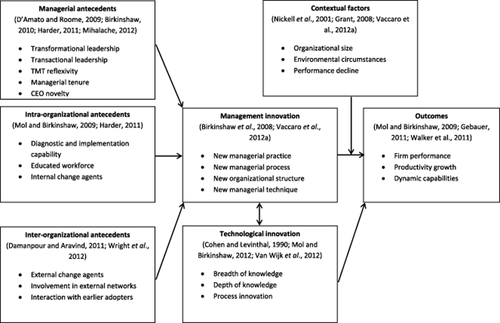

Innovation is a highly diverse field, as is evident in the multitude of theoretical perspectives and empirical constructs that have been brought to bear on the topic. To facilitate the accumulation of scientific knowledge of management innovation, we provide an integral framework that highlights the main antecedents and outcomes of management innovation (see Figure 1). The framework identifies common areas of research in terms of antecedents of management innovation (managerial, intra-organizational, and inter-organizational); dimensions of management innovation (new practices, processes, structures and techniques); outcomes of management innovation in terms of various dimensions of performance (e.g., firm performance, productivity growth, quality of work, group satisfaction); and contextual factors that affect management innovation (such as organizational size and competitiveness of the industry).

Integrative framework of management innovation

The framework is used to identify where research findings about management innovation converge in this relatively new field and where gaps in our understanding exist. Below we discuss the building blocks and outcomes of management innovation as well as the contextual factors that affect it.

Managerial antecedents of management innovation

Several scholars have investigated leadership variables (e.g., Birkinshaw, 2010; Vaccaro et al., 2012a), chief executive officer (CEO) and top management team (TMT) demographics (such as CEO novelty, Harder, 2011; TMT reflexivity, Mihalache, 2012), and management characteristics (such as managerial tenure and managerial education, e.g., Kimberly and Evanisko, 1981; Damanpour and Schneider, 2006), and their effect on management innovation. Vaccaro et al. (2012a) showed in a large-sample study as well as in an in-depth case study of DSM Anti-Infectives (Vaccaro et al., 2012b) that employing both transformational as well as transactional leadership behaviours facilitates the pursuit of management innovation by allowing management to stress the achievement of results while also encouraging experimentation with new practices, processes and structures. Transformational leaders who inspire team success and develop trusting and respectful relationships based on common goals enable organizations to pursue changes in management practices, processes or structures. Transactional leadership, on the other hand, may be helpful in the implementation of management innovation by inducing organizational members to attempt to meet targets; not only by means of trusted management methods, but also by setting targets and rewarding organizational members contingent upon the attainment of goals associated with management innovation.

Intra-organizational antecedents of management annovation

Others scholars have chosen to focus more on the micro-foundations of management innovation such as learning routines, resource allocation mechanisms and incentive systems in the organization. The paper by Khanagha et al. (2013) in this special issue shows that these micro-foundations are essential for realizing management innovations; we can see this in terms of new structural forms that facilitated the adoption of cloud computing. Moreover, a critical mass of internal change agents (Vaccaro et al., 2012b) and an educated workforce (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009), are both essential for realizing management innovations. Following Birkinshaw et al. (2008), we propose that internal change agents play a particularly relevant role as they are the individuals championing the introduction of management innovation in order to make organizations more effective. In a longitudinal study of the adoption of self-managing teams at the DSM Anti-Infectives plant (Vaccaro et al., 2012b), internal change agents at different hierarchical levels contributed to the pursuit of management innovation. While the plant managers created a conducive environment, at the operational level, front-line employees and their supervisors were the key change agents who implemented and operated with new practices, processes, and structures.

Inter-organizational antecedents of management innovation

The pursuit of management innovation is also influenced by external change agents as new practices, processes or structures are often shaped by third parties such as consultants and academics (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). In particular, consultants are seen by many as key agents in getting new management ideas and practices adopted within organizations (Sturdy et al., 2009). Gaining knowledge from external sources and learning from partners are critical inter-organizational antecedents of management innovation (Volberda et al., 2010; Damanpour and Aravind, 2011; Hollen et al., 2013). Also, social embeddedness, network position, and other factors influence the absorption of new management innovations outside the firm or even outside the industry. The study by Hollen et al. (2013) in this special issue shows how management innovations of established process-manufacturing firms are triggered by the use of shared external test facilities. This intra-organizational context facilitated these firms to develop new-to-the-firm management activities to foster technological process innovation, namely setting objectives, motivating employees, coordinating activities and decision-making.

Technological innovation

Technological innovation can be defined at different levels (Damanpour, 1987). At a narrower level, technological innovation involves the generation and adoption of a new idea concerning physical equipment, techniques, tools, or systems which extend a firm's capabilities into operational processes and production systems (e.g., Evan, 1966; Schon, 1967; Damanpour, 1987; Damanpour et al., 2009). However, a discovery which provides no economic value and which never spreads beyond those who came up with the initial idea remains an invention (Garcia and Calantone, 2002). At a broader level, technological innovation also involves new products, services, and processes to produce and deliver them (Mishra and Srinivasan, 2005; Crossan and Apaydin, 2010; Van Wijk et al., 2012: Volberda et al., 2012). Consequently, at this level it can be defined as the generation and adoption of a new idea into operational processes, production systems, products and services.

Dimensions of management innovation

Mol and Birkinshaw (2009) distinguished several dimensions of management innovation. Management practices refer to what managers do as part of their job on a day-to-day basis and include setting objectives and associated procedures, arranging tasks and functions, developing talent, and meeting various demands from stakeholders (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009). The introduction of self-managed teams at Procter & Gamble changed the work of managers in that employees became in charge of setting their own goals and deciding when and how tasks were going to be performed (Vaccaro et al., 2012a). Management processes refer to the routines that govern the work of managers, drawing from abstract ideas and turning them into actionable tools. These routines include strategic planning, project management, and performance assessment (Hamel, 2006, 2007; Birkinshaw et al., 2008). After self-managed teams were introduced at Procter & Gamble, the reward and promotion systems were overhauled. Pay was determined on the basis of skill levels, which in turn served as the basis for promotion, as evaluated by fellow team members (Vaccaro et al., 2012a). Organizational structure refers to how organizations arrange their communication, and how they align and harness the efforts of their members (Volberda, 1996; Hamel, 2007; Birkinshaw et al., 2008). The organizational structure was also altered at Procter & Gamble as hierarchical layers were removed following the adoption of self-managed teams. A management technique involves a tool, approach, or technique which is adopted in a business framework (Waddell and Mallen, 2001). One such new management technique is the balanced score card (Birkinshaw et al., 2008).

Contextual factors that affect management innovation

Several internal and external contextual variables trigger management innovation. For instance, larger firms have been shown to be more resourceful than smaller ones, but their need to introduce new management innovations is also greater (Kimberly and Evanisko, 1981; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009). Moreover, work by Vaccaro et al. (2012a) showed that the effect of transformational leadership on management innovation increases with size. Apparently, transformational leadership has little effect on the pursuit of management innovation in small firms. On the other hand, the study showed that transactional leadership affects management innovation mainly in small organizations. Challenging economic conditions also trigger management innovation, but may also constrain the number of options a firm has to respond because of limited resources (Nickell et al., 2001). The need to adapt to changing environmental conditions is often what provides the spur to successful management innovation (Grant, 2008). For instance, scarcity of materials triggered the development of Toyota's lean management system (Grant, 2008). The study by Hecker and Ganter (2013) in this special issue shows how the level of product market competition affects technological as well as management innovation. They provide a contingency perspective on various types of innovation and find that, in management innovation, the intensity of competition has a positive effect on the firm's propensity to adopt workplace and knowledge management innovation.

Outcomes of management innovation

Management innovation has a positive effect on the development of dynamic capabilities (Gebauer, 2011), on productivity growth (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2009), and on firm performance (Walker et al., 2011). It is mainly related with the effectiveness and efficiency of internal organizational processes (e.g., Adams et al., 2006; Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2011). The hard performance outcomes typically used to measure management innovation include profitability, productivity, growth and (sustainable) competitive advantage. However, management innovation does not only result in the achievement of ‘hard’ goals, but also softer targets (Birkinshaw et al., 2008). For instance, management innovation can decrease employee turnover (Hamel, 2011; Kossek, 1987), increase customer satisfaction (Linderman et al., 2004), and increase the satisfaction and motivation of other stakeholders, such as employees (e.g., Mele and Colurcio, 2006). It can also influence a firm's environmental impact (e.g., Theyel, 2000; Martin et al., 2012).

In the remainder of this paper, we further discuss the emerging themes of management innovation derived from our framework, address the performance implications, and raise some major issues for further research. Subsequently, we position the papers included in this special issue and explain how they address several issues of our research agenda. In the concluding section, we set some research priorities to further advance the field of management innovation.

Emerging research themes of management innovation

The framework of Figure 1 also points to emerging themes that are as yet under-researched. For instance, the multidirectional causalities between management innovation and technological innovation and the differential effects on performance are a source of much debate in the innovation field.

Debate 1: the relationship between management innovation and technological innovation

Much research needs to be done to examine the relationship between these two forms of innovation. Although it has been argued that management innovation is often an antecedent of technological innovation (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2012), considerably more research is needed to examine how management innovation is related to technological innovation. Several papers in this special issue address this question. The socio-technical perspective implies that changes in the technical system should be matched with changes in the social-system, that is, management activities, of a firm to optimize its outcome (e.g., Damanpour and Evan, 1984). The paper by Hecker and Ganter (2013) in this special issue suggests that management innovation and new technological knowledge are positively related to each other. The paper by Hollen et al. (2013) provides an overview of three different perspectives on the relationship between management innovation and technological innovation: that technological innovation mainly precedes the achievement of management innovation, or vice versa, or that both types of innovation are mutually interdependent and are thus intertwined over time. Mol and Birkinshaw (2012) argued that management innovation often leads to technological innovation. However, other scholars (Heij et al., 2013) argued that management innovation and new technological knowledge have a J-shaped interaction effect on innovation success. Where there are low levels of management innovation, adjustments in management practices, processes, structures and techniques are not adequately aligned with, new technological knowledge in ways that enable the firm to achieve innovation success. Higher levels of management innovation show how better adjustment can lead to much greater innovation success (Heij et al., 2013). Consequently, innovation processes are complex (Daft, 1978) and future research is needed to further uncover the relationship between management innovation and technological innovation.

Debate 2: the performance effects of management innovation versus technological innovation

There is much ambiguity about the differential effects of management innovation versus technological innovation. The aim of future research should be to conduct a systematic investigation and development of the various ways in which management innovation and its leverage of technological innovation can be enhanced within a firm, between firms through open innovation networks, and during interaction with institutional stakeholders, as well as through better measurement and monitoring in general. In comparison to technological innovations – measured by deployment of budgets, numbers of scientists involved, numbers of patents or simply by R&D expenses as percentage of turnover – management innovations in terms of outstanding managerial capabilities, management practices (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2006) and organizing principles of innovation are more difficult to assess and quantify.

Despite the increasing awareness of the importance of management innovation for competitiveness, the empirical basis for measuring management innovation is still patchy and weak (cf. Armbruster, 2006). This is an important issue to address. The findings of the Erasmus Innovation Monitor covering the years 2006 to 2010 (Volberda et al., 2010) indicate that the attributes of management innovation are of great importance and explain about 50–75% of the variation in innovation performance between Dutch firms. Furthermore, in controlled experiments on management innovations in firms, TNO – a Dutch institute for applied research – reported productivity increases of firms that implemented management innovations (such as lean, self-managing teams) of up to 16% and a substantial reduction of throughput times (cf. Totterdill et al., 2002). Moreover, Vaccaro et al. (2012b) show how the adoption of self-managing teams within DSM Anti-Infectives resulted in increased productivity (12%), improvements in process technology, savings in maintenance and operation, lower costs and better accomplishment of targets. But soft performance variables such as the increase in participatory behaviour in social processes, higher health standards, environmental upgrading, and even happiness, are also important outcomes of management innovation. For instance, putting in place new practices, processes and structures involving self-managing teams within DSM Anti-Infectives resulted in a greater sense of mission, more trust, a better interaction between different constituencies, more exchange of knowledge and a highly motivated and engaged workforce.

Future research agenda and positioning of the papers

In this special issue, we want to stimulate academic inquiry by providing a platform for sharing ideas and state-of-the art research on management innovation. On the basis of the integrative framework of management innovation and the emerging research themes which we derived from it, we developed a ‘research agenda for future research in management innovation’ (see Box A). In particular, we formulated a list of future research issues for which we have drawn on the conceptual contributions in the innovation literature, the multilevel antecedents of management innovation (managerial, intra-organizational, and inter-organizational), the consequences of management innovation, and the methodological approaches in management innovation research.

Box A. Management innovation: future research issues

- Conceptualization of management innovation:

- What are the levels of analysis at which management innovation should be considered?

- How to define management innovation on the basis of generic, context-neutral management activities?

- How to define management innovation: as an encompassing construct (e.g., incorporating organizational innovation) and/or differentiation in several management innovation types?

- Comparing different ways of defining management innovation and assessing their contribution to our understanding of management innovation?

- How to conceptualize management innovation as an outcome vs. as a process?

- How to define the degree of newness of management innovation?

- Managerial antecedents of management innovation:

- Who are the actors that drive management innovation?

- What is the role of top/middle/line managers in management innovation?

- Is the generation of management innovation a top-down and/or a bottom-up process?

- Intra-organizational antecedents of management innovation:

- What is the role of internal change agents?

- What are the organizational conditions that stimulate the introduction of management innovations?

- Inter-organizational antecedents of management innovation:

- What is the role of external change agents?

- How does management innovation emerge in inter-organizational relations?

- Which factors trigger management innovation in an inter-organizational context?

- How to develop conceptual frameworks of management innovation focusing on the dynamics of co-evolutionary interactions at both firm and industry level?

- Relationships between management innovation and technological innovation:

- How to conceptualize different causal relationships between management innovation and technological innovation?

- How are management innovation and technological innovation related to each other over time and which conditions influence their relationship?

- To what extent do complementarities exist between management innovation and technological innovation and how do these complementarities impact performance?

- Consequences of management innovation:

- What are the implications of management innovation for firm performance in different environmental conditions?

- To what extent does management innovation contribute to sustainable competitive advantage?

- For what outcomes other than financial performance may management innovation be important?

- Methodological approaches in management innovation research:

- How to measure management innovation?

- How to develop appropriate scales for measuring management innovation?

- How to obtain objective measures of management innovation?

- How do conceptual frameworks, simulation and laboratory research, in-depth case studies, longitudinal case studies and international comparative survey research increase our understanding of management innovation?

At a EURAM mini-conference on management innovation at the Rotterdam School of Management, more than 40 empirical, conceptual, and practitioner-oriented papers from a plurality of theoretical perspectives, units of analyses, contexts, and research designs were presented. In this special issue, we selected those papers that deepen our understanding of management innovation in several ways and provide answers to various future research issues (see Box B).

Box B. Contribution of the three papers regarding future research issues in the management innovation field

| Future research issue | Hecker and Ganter | Hollen et al. | Khanagha et al. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptualization of management innovation | Based on empirical definition of organizational innovation and of various types of management innovation (OECD/EURSTAT). | Based on four conceptually separate and context-neutral sets of management activities (Birkinshaw, 2010). | New to the firm structures, practices and processes |

| Managerial antecedents of management innovation | (–) | Management innovation is driven both top-down (key role of higher management) and bottom-up (key role of project leaders in external test facilities). | Learning routines of managers |

| Intra-organizational antecedents of management innovation | R&D intensity; share of employees with a degree. | Management innovation is triggered by intra-organizational tensions to reconcile pressures for exploration and exploitation across subsequent phases of technological process innovation. | Routines and capabilities, resources and complementary assets and incentive structures. |

| Inter-organizational antecedents and contextual factors of management innovation | Various, e.g. speed of technological change; intensity of competition; product homogeneity. | Management innovation is triggered by the inter-organizational context in the form of external test facilities available to firms for enabling technological process innovation. | Interaction of Technology Intelligence experts with outside partners such as Google, IBM, Intel and universities |

| Relationships between management innovation and technological innovation | Relationship between intensity of competition and firm innovation types (i.e., technological innovation and three types of management innovation). | Three perspectives, with main focus on the perspective that both types of innovation are combined over time in an intertwined way. | Management innovation proceeds technological innovation: adaptation in structure is as precursor of technology adoption |

| Consequences of management innovation | (–) | Difficult to imitate by competitors due to embeddedness in the context of inter-organizational relationships. | Adoption of an emerging core technology |

| Methodological approaches in management innovation research | Quantitative analysis of public survey data (in Germany). | Development of a conceptual framework and propositions regarding the role of management innovation in enabling technological process innovation. | In-depth case study of a global telecommunication firm: semi-structured interviews, focus group sessions and field study observations |

Hecker and Ganter (2013) examine in their paper how external contingency factors – product market competition and rapid technological change – are related to management innovation and technological innovation. The authors find that product market competition has an inverted U-shaped relationship with a firm's preference for introducing technological innovation, and has a positive relationship with management innovation. Furthermore, they provide new insights into how management innovation is associated with rapid technological change. The authors underline that the relationship between innovation and competition should include a contingency perspective.

The conceptual paper by Hollen et al. (2013) uses an inter-organizational perspective to examine how different new-to-the-firm management activities are required for performing technological process development in an external test facility, thereby enabling the firm to achieve technological process innovation. The authors argue that making use of this inter-organizational context and the associated required management innovation allow a firm to overcome intra-organizational tensions and so to reconcile competing pressures for exploration of new and exploitation of existing process technologies. One of the authors' conclusions is that an inter-organizational level of analysis broadens the group of external change agents that may influence management innovation.

The paper by Khanagha et al. (2013) examines how management innovation is related to the adoption of an emerging core technology. The authors argue that relatively few scholars have examined how management innovation is related to an incumbent's success in adopting an emerging technology. By studying the adoption of cloud computing in a large multinational telecommunication firm, the authors find that management innovation is required in order to accumulate knowledge of emerging technologies in a dynamic environment. They highlight how a novel structural approach enables a firm to overcome inertia and to adopt an emerging core technology.

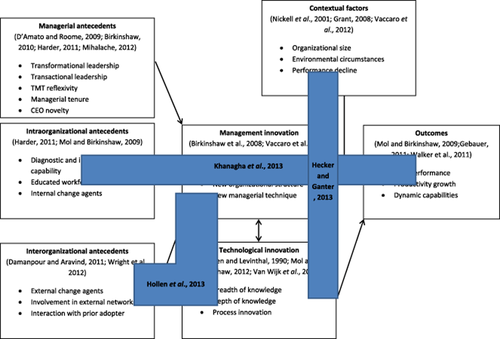

These three papers can easily be plotted into our integrative framework of management innovation (see Figure 2).

Integrative framework of management innovation

The paper by Hollen et al. (2013) is mainly conceptual and takes both a firm and an inter-organizational perspective by examining how new-to-the-firm management activities enable technological process development in an inter-organizational context of an external test facility, leading to eventual technological process innovation within the firm. The paper provides new insights as to how management innovation enables technological process innovation. By contrast, in their paper Khanagha et al. (2013) examine how management innovation enables technological innovation. They find that adaptation in the structure is a precursor of technology adoption. The paper by Hecker and Ganter (2013) complements these two papers. Using German data of the Community Innovation Survey (CIS), the authors examine how technological dynamic markets are associated with management innovation. They also provide new insights how the degree of product market competition influences technological innovation and management innovation. However, in contrast to Hollen et al. (2013) and Khanagha et al. (2013), these authors do not elaborate on the sequence of management innovation versus technological innovation, but do provide further insights in the significantly different determinants of technological and management innovation.

Priorities in management innovation research

How should we continue our journey into management innovation research and focus on management as a fertile ground for innovation? Although research into management innovation has gained momentum over recent years, among all different subsets of innovation it is still relatively under-researched (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010). Considering our research agenda as described in Box A and the contributions of the papers as described in Box B, we therefore have to set priorities (see Box C).

Box C. Priorities in management innovation research

- Conceptualizing and defining management innovation in complementary ways.

- Investigating complementarities between management innovation and technological innovation and the impact on performance.

- Pluralism in research methods including:

- Developing conceptual frameworks regarding management innovation;

- Management innovation laboratory research;

- Longitudinal and in-depth case study research;

- Comparative large-scale cross-country survey research among firms.

- Effects on exploratory innovation.

- Generic vs. firm-specific management innovations.

As emphasized before, the progress of research in management innovation and the accumulation of knowledge will depend on how management innovation is conceptualized and defined. While definitions can illuminate, too much variety can also hamper progress. Striking a balance therefore becomes imperative. We suggest, therefore, that with management innovation research currently in an embryonic stage of development, it is important to have some degree of variety in definition, though these definitions need to complement one another. The definitions of management innovation used by Hollen et al. (2013) and Hecker and Ganter (2013) illustrate this point: the first is based on a generic conceptual definition of management activities (Birkinshaw, 2010), while the latter provides three empirically-related sub-types of management innovation: workplace organization, knowledge-management, and external relations. In a similar way, Volberda et al. (2006) distinguished management innovation into new organizational forms, dynamic managerial capabilities, new ways of working, and co-creation. These theories and empirically-driven conceptualizations address management innovation from different perspectives and may usefully complement each other.

The second priority is the need to understand how management innovation and technological innovation are related, taking a complementary perspective (Milgrom and Roberts, 1995). As discussed above, at present three perspectives could be discerned regarding the relationship between management innovation and technological innovation: management innovation preceding technological innovation, technological innovation preceding management innovation, and a third one, namely dual interactions between management innovation and technological innovation over time. In all three perspectives, management innovation and technological innovation are in a sense complementary. While technological innovations are developed within organizational boundaries (whether within the firm itself or within an external laboratory), management innovations seem to emerge through interactions with the outside world or, as Birkinshaw and Mol (2006: 82) observe, ‘on the fringes of the organization rather than the core’. It is important to increase our understanding of the nature and temporal processes of complementarity in each perspective and of the subsequent impact on performance. A more co-evolutionary approach to studying the development and introduction of management innovation versus technological innovation over time, one which involves different levels of analysis and also takes into account institutional and environmental changes as well as the intentions of management, could be very promising (Huygens et al., 2001; Volberda and Lewin, 2003).

Our third priority should be to examine the usefulness of pluralism in research methods as a means of speeding up the contributions of management innovation research to establish a more coherent body of knowledge. Many papers on innovation are cross-sectional (Damanpour et al., 2009) or focused on one type of innovation (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010). Future research should examine with a longitudinal research design how management innovation may complement other types of innovation. Longitudinal and in-depth case studies are important for unravelling causality issues, process dimensions and the role of power in implementing management innovation. Moreover, research on management innovation via simulations, laboratory research and participative field research will increase our understanding of complex management innovation processes involving several levels of analysis. Comparative research among firms using large-scale cross-country surveys will reveal the impact on management innovation of factors such as the national institutional environment, but may also provide insights into how management innovation is diffused across countries, and what affects that process.

Over the last couple of years several such initiatives have been started in order to gain new knowledge on management innovation. These initiatives include the Management Innovation Lab (MLab) in London, the Management Innovation eXchange (MIX), and the Erasmus Competition and Innovation Monitor. In the MLab, academics, organizations, institutions and some other stakeholders work together to enable management innovation. The Erasmus Competition and Innovation Monitor, developed by INSCOPE, measures the level of management innovation of firms over time in the Netherlands. INSCOPE, a joint initiative by several universities and research institutes, aims to increase the fundamental understanding of management innovation and its influence on technological innovation, productivity and competitiveness of firms. In addition to the Erasmus Competition and Innovation Monitor, INSCOPE also conducts research on specific industry contexts, such as the Dutch care industry and the Port of Rotterdam. In collaboration with local partners, INSCOPE is also expanding its annual measurement of management innovation to cover other countries, such as Belgium, the UK, Germany and Italy. Such international measurements provide opportunities to detect differences between countries which can act as a foundation for increasing the competitiveness of firms or even certain industries or national economies as a whole.

The fourth priority concerns the effect of management innovation on exploration. Management innovation relates mainly to the effectiveness and efficiency of internal organizational processes (e.g., Adams et al., 2006; Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2011). However, few scholars have examined how management innovation contributes to exploratory innovation. To survive in the short term and in the longer run, firms need to invest sufficiently in exploration and exploitation (March, 1991; Levinthal and March, 1993) and process management practices may affect exploration (Benner and Tushman, 2002). For instance, Douglas and Judge (2001) argued that in firms with a more exploration-oriented structure, implementation of TQM practices is more strongly related to performance. Future research should examine how management innovation is related to exploratory innovation.

The fifth research priority is to examine the extent to which management innovations are generic or specific. The existing literature on management innovation is either conceptual (e.g., Benner and Tushman, 2003; Hamel, 2006) or operationalized as a specific type of management innovation, such as TQM or ISO certifications (e.g., Benner and Tushman, 2002). However, the operationalization of management innovation as a very specific type of management may raise certain concerns. For example, De Cock and Hipkin (1997) suggested that a specific management innovation has a rather short life expectancy, because managers quickly move beyond a specific management innovation to further increase organizational effectiveness. Additionally, the adoption and diffusion of management innovations are firm-specific, dependent on the context and do not generate uniform outcomes (De Cock and Hipkin, 1997; Ansari et al., 2010; Damanpour and Aravind, 2011). Even within a certain management innovation, varying results can be obtained due to different practices that various firms implement (Zbaracki, 1998; Benner and Tushman, 2002). Furthermore, the distinction among specific management innovations can be rather vague and the underlying philosophies, tools and techniques of certain management innovations may have a large overlap (Currie, 1999; Parast, 2011). On the other hand, different types of management innovation may be interdependent (Currie, 1999) and firms that adopt particular innovations are more likely to adopt other, related management innovations (Lorente et al., 1999). Future research should examine whether management innovation should be considered and measured as a generic construct or based on specific types of management innovation (Mol and Birkinshaw 2009; Van den Bosch, 2012; Vaccaro et al., 2012a).

Conclusion

While innovation is surprisingly one of the most addressed topics in practitioner as well as academic outlets, most research has tended to address innovation as the development of new technology, products and services. As a consequence, technological innovation has dominated innovation research, with related notions such as product development, radical versus incremental innovation, as well as diffusion and adoption receiving most attention. However, falling trade-barriers, decreasing transaction costs, stagnating developed markets and overheating emerging markets are forcing firms to look for other areas in which to innovate as a means of gaining and maintaining competitive advantage. This entails a search not only for new products and new technologies but also for changes in the nature of management within the firm, that is, management innovation.

In this spirit, this introductory paper has briefly reviewed progress in innovation research and claimed that management itself may be a fertile ground for innovation. We have provided a clear conceptualization of this phenomenon and developed an integrative framework to advance our understanding of the various antecedents and outcomes of management innovation, as well as the contextual factors that affect management innovation. Moreover, we have provided a future research agenda and selected what are, in our view, the most important research priorities for advancing knowledge in the management innovation domain. We hope that the insights shared in this special issue will stimulate additional scholarly conversation on important innovation research topics as well as on the crucial role of new modes of management.