The Role of Management Innovation in Enabling Technological Process Innovation: An Inter-Organizational Perspective

Abstract

For sustained competitive advantage of established process manufacturing firms, technological process innovation to improve resource productivity and environmental performance has become of pivotal importance. These firms, however, often face intra-organizational tensions to reconcile pressures for exploration and exploitation across subsequent phases of technological process innovation. Firms may, therefore, need to perform the development phase – being the most sensitive to these tensions – in the inter-organizational context of an external dedicated development facility. This requires new-to-the-firm management activities, i.e., management innovation. However, the role of management innovation in enabling technological process innovation in an inter-organizational context remains largely unexplored. To address this gap, in developing propositions we use illustrative examples from the research context of an external development facility for sustainable process technology. The paper has two contributions. First, by adopting a process perspective we are able to clarify how both types of innovation are combined over time in an intertwined way. Second, we extend management innovation theory by conceptualizing management innovation in an inter-organizational context. We conclude with implications for theory, practice and future research.

Introduction

Competitive dynamics driven by technological, regulatory and economic changes have shaped an increasingly complex and turbulent business landscape. In order to cope with these dynamics and to secure future viability, innovation is imperative for established firms (Banbury and Mitchell, 1995; Tidd et al., 2005; Crossan and Apaydin, 2010). By focusing on the fact that firms organize their innovation efforts through R&D activities, many scholars have developed innovation theories from studies of technological innovation in the manufacturing sector (Damanpour and Aravind, 2012). Within the manufacturing sector, the pivotal importance of technological innovation to improve resource productivity and environmental performance has become particularly apparent in the context of the chemicals, aluminium, iron, steel, utility and other energy-intensive process manufacturing industries. Resource productivity improvements through fundamental technological process innovation are necessary due to many ecologically unsustainable practices in these industries in terms of pollution and consumption of scarce resources (Bhat, 1992; Shrivastava, 1995). As pointed out by Shrivastava (1995: 184), the regulatory and competitive landscape of these environmentally sensitive industries is ‘being shaped by numerous environmental regulations and standards that affect the costs of doing business'. By enforcing reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption and waste disposal, these regulations trigger established firms to embrace a shift towards proactive environmental management as part of their competitive strategies (Berry and Rondinelli, 1998).

Resource productivity improvements that lead to higher environmental performance also increase firms' competitiveness (Esty and Porter, 1998; Porter and Van Der Linde, 1995) by, for instance, lowering production costs. This is particularly relevant for established energy-intensive process manufacturing firms to remain competitive in countries with increasing energy prices and environmental requirements, like countries in the European Union, and to be able to compete with, for instance, firms in the United States which, in contrast to many European firms, can often use cheap shale gas for their production processes. Established process manufacturing firms need, therefore, to come up with technological process innovations to switch to more sustainable and efficient modes of production that allow for a higher degree of reduction, reuse and recycling of raw materials, energy and residual streams in their full-scale production system.

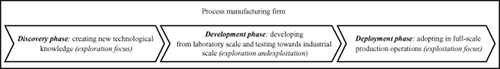

Technological process innovation (i.e., innovation within a firm's production system) means that a firm has gone beyond the generation of a new idea and begins to apply (i.e., adopt) the resulting new technological process element(s) in manufacturing operations (Knight, 1967). Pisano (1997: 25) pointed out that technological process innovation ‘spans multiple functions, from research laboratories to pilot plants to full-scale commercial production environments’. In line with this observation and with Malnight's (2001) process-based analysis, this paper distinguishes three phases in technological process innovation: (1) discovery; (2) development; and (3) deployment (see Figure 1). These phases are associated with what Li et al. (2008) refer to as, respectively, the science, technology and product market functions along a firm's value chain.

Intra-organizational perspective on technological process innovation: three phases

The discovery phase, which often takes place in the laboratory, refers to the discovery (including research) of new technological process elements by creating new technological knowledge (Anderson and Tushman, 1990) or by combining existing technological knowledge in a new way (Henderson and Clark, 1990). An example is the creation of a new membrane separation technology as an alternative to distillation to separate chemical compounds in process manufacturing. In this phase, the focus is mainly on exploration (March, 1991). In the subsequent development phase, this new membrane technology has to be developed from laboratory scale and tested towards industrial scale. In this intermediate phase, the focus is on both exploration (new knowledge about how to scale up, e.g., from separating two liquids by membrane technology at laboratory scale to full-scale in the context of a new or existing chemical factory) and exploitation (using existing technological knowledge on scaling up). These foci are contradictory logics according to March's (1991) exploration/exploitation dichotomy. Finally, when scaled up and tested successfully, the newly developed membrane separation technology needs to become operational in the firm's full-scale production system. In this deployment phase, the focus is mainly on the exploitation of already acquired technological process knowledge and current production techniques (Li et al., 2008), requiring a significantly different nature of organizational knowledge creation, i.e., aimed at making existing processes more efficient, compared to earlier phases of technological process innovation (Hatch and Mowery, 1998).

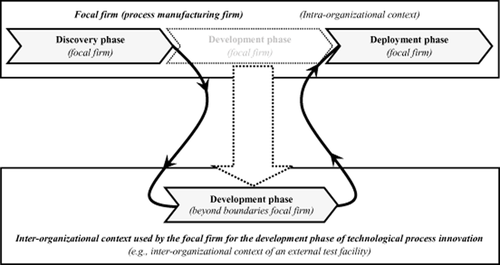

The development phase hence functions as a bridge between an exploration-dominated (discovery) and an exploitation-dominated (deployment) mindset of process manufacturing firms. Various scholars have pointed out that established firms encounter difficulties in dealing with contradictory intra-organizational pressures for exploration and exploitation (March, 1991; Burgers et al., 2008; O'Reilly and Tushman, 2008; Jansen et al., 2009; Russo and Vurro, 2010). As a result, many promising technological process improvements do not pass the development phase, or are too time-consuming to be truly competitive (Pisano, 1997; Collins et al., 1988; Hatch and Mowery, 1998; Macher, 2006). Firms may overcome the associated exploration/exploitation paradox by partnering with other firms and organizations (Baden-Fuller and Volberda, 1997; Russo and Vurro, 2010). Hence, for technological process development efforts to be effective, these efforts may need to be conducted in an inter-organizational context (i.e., beyond the organizational boundaries) by including parties external to the focal firm (Håkansson, 1987; Laage-Hellman, 1987; Russo and Vurro, 2010), for example, in the inter-organizational context of an external test facility, as illustrated in Figure 2. These firms remain fully involved in and responsible for (i.e., in full control of) conducting the associated technological process development activities, while these activities take place outside their organizational boundaries (Van Den Bosch et al., 2011).

Technological process innovation with the development phase performed in the inter-organizational context

This kind of external test facilities provides a context-neutral place (as it is not located within the organizational boundaries of the firms that use these test facilities), specialized technical support for technological process development and, as there are often multiple firms located in the same test facility, may facilitate firms to come into contact with (projects or engineers from) other innovative process manufacturing firms. Such external test facilities could be perceived as a key factor of change that enables established process manufacturing firms to perform the development phase of technological process innovation beyond their organizational boundaries.

Technological process innovation is rooted in technological problem solving, yet it must be broadly integrated with other organizational processes (Pisano, 1997). Based on Meeus and Edquist's (2006) classification of innovation, Damanpour et al. (2009) distinguished two types of changes in organizational processes: technological process innovation and administrative process innovation. As the latter implies changes in the way firms are managed, it has also been labelled management innovation (e.g., Birkinshaw et al., 2008) or managerial innovation (e.g., Damanpour and Aravind, 2012). In this paper, we follow Birkinshaw et al. (2008) by using the term management innovation. Technological process innovation and management innovation are both organization-specific and are inextricably related to each other (Daft, 1978; Collins et al., 1988), being associated with the ‘dual core’ processes of organizations (Daft, 1978: 209). In this paper, we argue that successfully performing the development phase of technological process innovation in an external test facility requires management innovation. Previous literature has already emphasized the importance of realizing both management innovation and technological innovation in order to further organizational goals (Ettlie, 1988; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2006; Schmidt and Rammer, 2007; Damanpour et al., 2009; Battisti and Stoneman, 2010; Evangelista and Vezzani, 2010; Camisón and Villar-López, 2012; Sapprasert and Clausen, 2012). However, the role of management innovation in enabling technological (process) innovation in an inter-organizational context remains largely unexplored in the literature.

The aim of this conceptual paper is to address this gap by gaining a better understanding of the role of management innovation in enabling firms to perform the development phase of technological process innovation in the inter-organizational context of an external test facility. To provide an empirical research context, the paper uses illustrations from established process manufacturing firms that perform this development phase in an external dedicated development facility for sustainable process technology.

This external dedicated development facility (‘external test facility’) is located in the Port of Rotterdam (the Netherlands), which has one of Europe's largest petrochemical complexes (Van Den Bosch et al., 2011). It has been initiated by a consortium of various Dutch organizations and governmental agencies. By facilitating the development phase of technological process innovation of established process manufacturing firms, it fulfils a bridge function between the laboratory phase and the deployment phase. The test facility is a limited-liability company and is open to all firms aiming to develop technologies that contribute to a more sustainable society. The facility offers various industrial utilities and intermediates the storage and handling of chemicals. Besides these utilities and logistics facilities, there is a machine park and equipped office space. Support can be provided whenever necessary, including licensing and safety advice, maintenance and technical support. Moreover, the test facility has received an ‘umbrella licence’ from the regional environmental protection agency that reduces the permit procedure duration per pilot from several months or even years to less than six weeks.

We collected public and company documents and interviewed the facility's director as well as involved managers from three established process manufacturing firms that have started a project in this facility to scale up, test and/or demonstrate promising sustainable process technologies. All these firms encountered difficulties to internally develop technological process innovations, and were interviewed about new-to-the-firm changes in management activities needed to successfully develop technological process innovations by making use of this external test facility. The process research in this conceptual paper builds on their narratives.

The contributions of this paper to the literature are twofold. First, we contribute to an increased understanding of the relationship between management innovation and technological (process) innovation. Second, we extend and advance the management innovation theory and research by focusing on the inter-organizational context. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, prior research on technological process innovation, management innovation and their interrelation is reviewed, and we elaborate on how established process manufacturing firms may be challenged to perform the development phase of technological process innovation in the inter-organizational context of an external test facility. Taking this inter-organizational perspective, we then develop propositions on the role of new-to-the-firm management activities, i.e., management innovation. We conclude with implications for theory, practice and future research.

Literature review

Technological process innovation and intra-organizational tensions

Technological innovation can refer to both products and processes (see Table 1). Technological product innovation implies the creation of new products, based on new or combined technologies, which are being sold in the market (Utterback and Abernathy, 1975; Meeus and Edquist, 2006). In contrast, technological process innovation implies the introduction of new input materials, physical equipment or software systems in a firm's production or service operations in which products and services are delivered (Ettlie and Reza, 1992; Damanpour and Gopalakrishnan, 2001; Meeus and Edquist, 2006). In the context of process manufacturing, their introduction changes how products are produced (Meeus and Edquist, 2006). Whereas technological product innovation has received substantial attention in the literature, technological process innovation is still underexplored and requires additional research (Reichstein and Salter, 2006; Keupp et al., 2012).

|

Technological process innovation may lead to, among others, lower production costs, product quality improvements, lower disposal costs and the ability to use cheaper raw materials (e.g., Laage-Hellman, 1987; Hatch and Mowery, 1998). These possible outcomes from technological process innovation imply a more appropriate and efficient use of resources and are hence associated with enhanced resource productivity, which is ‘what makes companies truly competitive’ (Esty and Porter, 1998: 36). Enhanced resource productivity, in turn, implies better environmental performance (e.g., Shrivastava, 1995), due to which firms can better cope with environmental regulations (Porter and Van Der Linde, 1995). Hence, technological process innovation is an important strategic response to environmental issues and the related need for regulatory compliance (Skea, 1994). Furthermore, technological process development may well be ‘the hidden leverage in product development performance’ (Pisano, 1997: 4), as the speed and effectiveness of realizing technological process innovation shape the overall cost, timeliness and market performance of new product introductions (Calantone et al., 1995; Pisano, 1997; Zahra and Nielsen, 2002).

In order to enable technological process innovation, process manufacturing firms need to deal with tensions between contradictory pressures for exploration and exploitation encountered across the subsequent three phases of the innovation adoption process. The experimentation with and creation of new technological process elements in the discovery phase demands an exploratory mindset (March, 1991) that creates variety in experience (Holmqvist, 2004; Uotila et al., 2009) through revolutionary changes (Tushman and O'Reilly, 1996). In contrast, the deployment phase, in which these new process elements are used to produce products, demands an exploitative mindset and disciplined problem solving (Anderson and Tushman, 1990; Smith and Tushman, 2005) in order to achieve high reliability, accountability and reproducibility (Hannan and Freeman, 1984) and to utilize complementary assets (Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000; Stieglitz and Heine, 2007). The development phase needs to bridge these contradictory pressures for change and stability, which seems problematic for most established firms (Macher, 2006; Burgers et al., 2008; Jansen et al., 2009).

The associated intra-organizational tensions (e.g., Russo and Vurro, 2010) stem partly from the fact that personnel involved with shaping new process technologies ‘range from PhD scientists performing laboratory experiments and running esoteric computer simulations to shop-floor production workers who fine-tune equipment settings’ (Pisano, 1997: 25). Laboratory workers are mainly focused on continuous renewal of the production process and on further optimizing it from a technological knowledge perspective, whereas operational managers prefer low-risk exploitative processes. As pointed out by managers of established process manufacturing firms associated with the test facility described in the introduction, technological process innovations – complex innovations aimed at improving environmental performance in particular – may take a long time to develop and, if proved successfully, may require large changes in the current production process in order to implement these innovations. Operational managers, however, usually prefer to only experiment with incremental innovations leading to short-term results in terms of optimization of current production processes. As the dominant mindset in established firms is often focused on these short-term results, long-term technological process innovation projects are usually perceived as problematic. Furthermore, operational managers often indicate that they do not want the complex development of new technological process elements to take away attention from current round-the-clock production operations, leaving limited room for process technology development activities. As pointed out by Hatch and Mowery (1998), it draws scarce engineering resources away to debug these new elements, disrupting the existing manufacturing process.

The involvement in the development phase of both laboratory and operational managers, with different objectives and mindsets in terms of exploration and exploitation, reinforces ‘ “we versus they” thinking in regard to potential collaboration and knowledge development’ (Miles et al., 2000: 317). Moreover, the exploitative processes and incentives of the deployment phase, used by established manufacturing firms to keep focused on their main customers (Christensen and Bower, 1996), work so well in the short term that most established firms tend to have a preference for exploitation of existing technology and routines over exploration (Anderson and Tushman, 1990; Flier et al., 2003; Uotila et al., 2009). As a result, project leaders involved in internal development projects of established process manufacturing firms are often confronted with the fact that pilot installations integrated in the factory are not given priority when problems arise in existing full-scale manufacturing process. So when there are problems in the existing production operations, engineers are often removed from new technological process development projects in order to spend all their scarce time on fixing these problems, due to which the process development activities are delayed.

Furthermore, the extent to which established process manufacturing firms successfully realize pilot projects within the existing organizational context is generally limited due to a lack of autonomy for these projects from the current manufacturing environment, difficulties to obtain environmental permits for experiments within the firm, and restricting company rules, regulations and procedures that slow down or inhibit the projects' progress. Management may allow only minor changes in the production process out of fear that larger-scale changes cause regulatory problems (Pisano, 1997). In environmentally sensitive process manufacturing industries such as the (petro)chemical industries, rigid rules and regulations do often not allow any adaptation to the regular manufacturing process unless the required permits are obtained from external regulatory agencies. This often results from the fact that established firms operate in a compliance-fostering regulatory environment in which ‘doing the same in the same way’ (i.e., exploitation) is strongly stimulated (Suchman, 1995). Timely realization of technological process innovation is often frustrated by this dominant exploitation-minded intra-organizational context and the associated internal restrictions to change.

Management innovation

Scholars have started emphasizing that, in order to capture the full benefits of innovation, technological innovation needs to be combined with management innovation (e.g., Damanpour et al., 2009; Damanpour and Aravind, 2012). Birkinshaw et al. (2008: 829) defined management innovation as ‘the generation and implementation of a management practice, process, structure, or technique that is new to the state of the art and is intended to further organizational goals’. In this definition, ‘new to the state of the art’ implies management innovation without known precedents (Abrahamson, 1996). However, an ‘equally valid’ (Birkinshaw et al., 2008: 828) point of view in the literature regarding the novelty of management innovation – the one chosen in this paper – is that of being new to the adopting organization, i.e., new-to-the-firm (e.g., Stjernberg and Philips, 1993; Zbaracki, 1998; Damanpour et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2011; Vaccaro et al., 2012). At both levels of analysis, the innovation is seen as a significant departure from the past towards managerial activities and competencies that are better aligned with the competitive environment. New management practices, processes, structures and techniques imply changes in respectively the day-to-day activities of managers as part of their job in the organization (what managers do), the routines governing their work (how they do it), the organizational context in which their work is performed, and the associated techniques (Hamel, 2006, 2007; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2008; Vaccaro et al., 2012).

Birkinshaw et al. (2008: 828) noted, however, that ‘the distinctions among practice, process, structure, and technique are not clean, either conceptually or empirically’ and that ‘there are important similarities across the different forms of management innovation’. Therefore, this paper chooses an alternative way of conceptualizing management innovation by discerning – in line with Birkinshaw and Goddard (2009), Birkinshaw (2010) and Van Den Bosch (2012) – four conceptually separate and context-neutral sets of management activities. These activities, which collectively enable firms to achieve their aims (Birkinshaw, 2010), are associated with: (1) setting objectives; (2) motivating employees; (3) coordinating activities; and (4) decision making. Setting objectives relates to management activities regarding determining where the firm is going. Motivating employees relates to management activities to get employees to agree to the set objectives. Coordinating activities refers to the means by which managers organize and integrate activities of multiple groups or units. Finally, decision making is about making and communicating decisions regarding resource allocation. Management innovation implies new-to-the-firm changes in these four sets of management activities (see Table 2).

|

The level of analysis in management innovation research is, as asserted by Birkinshaw et al. (2008), mainly focused on the firm in interaction with the industry, country, individuals or the market for new ideas. However, these authors recommend future research to ‘give careful attention to the unit of analysis at which management innovation is studied, since there are several possible models that could be followed’ (Birkinshaw et al., 2008: 840–841). In this paper, we adopt an inter-organizational perspective of management innovation, i.e., how new-to-the-firm management activities arise in the context of new inter-organizational relations.

Enabling technological process innovation through management innovation

To manage the mentioned intra-organizational tensions associated with technological process innovation, established firms may choose to structurally separate exploratory activities, which require different processes, structures and cultures (O'Reilly and Tushman, 2004), from the dominant exploitation activities. Scholars have stated that such separation can be realized both within the firm – by structurally separating business units (Birkinshaw and Gibson, 2004; Jansen et al., 2009) – and by locating exploratory activities outside the organizational boundaries (Rothaermel and Deeds, 2004; Russo and Vurro, 2010). Dissatisfaction with intra-organizational tensions to reconcile pressures for exploration and exploitation, mainly caused by restrictions and restrained internal capabilities (e.g., Zahra and Nielsen, 2002), drives firms to interact and cooperate with other firms and organizations (Baden-Fuller and Volberda, 1997; Holmqvist, 2004). One way for top management to overcome these hurdles in technological process innovation is by using external test facilities. These test facilities provide firms the possibility to develop new technological processes in a neutral context, i.e., without dominant pressures for exploratory or exploitative behaviour.

Performing technological process development in an external test facility in order to enable technological process innovation involves knowledge creation outside the firm's boundaries as well as the subsequent integration of this externally acquired knowledge within its boundaries. The associated knowledge flows require managerial coordination (Stieglitz and Heine, 2007). Putting in place new-to-the-firm management activities of coordinating these processes needs to be complemented with new-to-the-firm management activities associated with setting objectives (from intra- to inter-organizational objectives), motivating employees (from intra- to inter-organizational work motivation) and with decision making (from intra- to inter-organizational resource allocation). These new-to-the-firm management activities are provided by and enabled in a bundle of idiosyncratic resources and capabilities in the inter-organizational context and, therefore, hard to imitate (Ritala and Ellonen, 2010), contributing to sustained competitive advantage for the focal firm (Mol and Birkinshaw, 2006). Extending the management innovation perspective of Birkinshaw and colleagues (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Birkinshaw and Goddard, 2009; Birkinshaw, 2010), we define management innovation in an inter-organizational context as firm-specific, new-to-the-firm management activities associated with setting objectives, motivating employees, coordinating activities and making decisions, which arise due to new inter-organizational relations and are intended to further organizational goals.

New-to-the-firm management activities associated with setting objectives

Managers pursuing new activities need to build legitimacy of these activities to make them acceptable, or justifiable, to the various (inter)organizational constituencies (Stjernberg and Philips, 1993; Stone and Brush, 1996; Birkinshaw et al., 2008). Related new objectives need to be set and evaluated to change individual behaviour towards the desired direction (Gruber and Niles, 1974; Suchman, 1995). Management innovation associated with new inter-organizational relations – aimed at overcoming intra-organizational tensions – implies new-to-the-firm management activities associated with formulating new objectives (Birkinshaw, 2010) to get: (1) managers and other involved employees of the focal firm to agree to perform activities in an inter-organizational context; (2) other firms within the inter-organizational context to agree to optimally contribute to these activities; and (3) other relevant stakeholders to support the inter-organizational approach. By setting new objectives, a firm may legitimize the engagement in inter-organizational relations in order to enable technological process innovation. For instance, established firms in the research context of the external test facility described before are often confronted with the fact that within the mindset of the people of the full-scale production department and according to internal firm standards, every pilot project that is initiated within the firm should be built for running a long time, for example, thirty years. This might be caused by the dominant idea that such a project is a capital expenditure and therefore needs to be developed as a long-term asset. However, only about three years of scheduled running time could in fact be needed to test and demonstrate a new process technology. By setting the new objective that pilot installations should (e.g., to save unnecessary costs) be built fit-for-purpose only, the start of a new pilot project in an external test facility for technological process innovation – where fit-for-purpose is easier to attain – can be partly legitimized.

New-to-the-firm management activities associated with motivating employees

Performing technological process development activities in an external test facility needs to be accompanied with putting in place new-to-the-firm management activities associated with motivating employees. New motivation schemes and incentives are needed that stimulate inter-organizational cooperation (e.g., Ring and Van De Ven, 1992) and the overall pursuit of fostering technological process innovation of the focal firm. The motivation of employees in an inter-organizational context, which can be based on extrinsic and intrinsic values, pertains to employees of the focal firm as well as to employees of other organizations involved in the development phase. The latter include staff under the payroll of test facilities, such as process operators, which might be working dedicated on a certain pilot project. These external employees (e.g., Lepak and Snell, 1999) need to be motivated to optimally contribute – based on procedures and a research programme of what needs to be tested, as provided by the focal firm – to the technological process development activities and purposes. This may require both behavioural and output control mechanisms (e.g., Dekker, 2004).

New-to-the-firm management activities associated with coordinating activities

Performing development phase activities beyond the focal firm's boundaries has to be effectively coordinated (e.g., Håkansson, 1987). In particular, the existing activities of the firm need to be aligned with the new activities that are provided by and enabled in the new-to-the-firm inter-organizational context. In this context, coordination might be focused on exploiting development experiences and/or resources of other organizations (Liebeskind et al., 1996) – which also include test facilities – and on producing new experiences jointly with these organizations by engaging in collective explorative undertakings (Laage-Hellman, 1987; Powell et al., 1996; Holmqvist, 2004; Santamaria and Surroca, 2011). In order to span organizational boundaries and to pull resources together, managers take on brokering roles (Hargadon and Sutton, 1997; Raisch et al., 2009). New-to-the-firm management activities associated with coordinating activities regarding a firm's knowledge creation outside its boundaries include the means by which managers integrate intra-organizational knowledge related to the discovery phase with the inter-organizational knowledge creation related to the development phase, as well as the means by which the latter phase is organized.

After completing the development phase in an external test facility by having developed and tested a new technological process element towards industrial scale, the externally acquired knowledge and related experiences need to be absorbed and integrated in order to realize the innovation's potential (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Hatch and Mowery, 1998; Van Den Bosch et al., 1999; Rothaermel and Alexandre, 2009). This integration of externally acquired knowledge and experience within the firm's boundaries and the associated translation into intra-organizational knowledge (e.g., Simonin, 1999) enable the focal firm to deploy the newly developed technological process elements in its full-scale production operations. The acquired knowledge will be both project-specific and generic (e.g., in terms of general knowledge of how to manage pilot projects in an external environment), and its integration within the firm's boundaries will involve new-to-be-learned managerial capabilities (e.g., Alcácer and Zhao, 2012). Schmidt and Rammer (2007) highlight that firms with the ability to incorporate externally sourced knowledge into their own innovation processes create more possibilities for realizing technological process innovation.

New-to-the-firm management activities associated with decision making

Performing the development phase of technological process innovation in external test facilities also needs to be accompanied by putting in place new-to-the-firm management activities associated with decision making about allocating resources, including human resources (e.g., Lepak and Snell, 1999). The responsible manager is required to find and allocate discretionary time for effectively managing this new endeavour (Gruber and Niles, 1974). Furthermore, the focal firm's resource base becomes enlarged with the external resources provided in the inter-organizational context of the test facility that are made available for use by the focal firm. This extended resource base requires new or adapted decision making activities that take the interaction with other organizations into account, for example, by highlighting inter-organizational decision making (Tuite et al., 2009). In order to promote inter-organizational knowledge sharing (e.g., Soekijad and Andriessen, 2003) in collective explorative undertakings, decision making in the inter-organizational context may need to be less hierarchically structured than would be the case within the established process manufacturing firm itself (e.g., Kellogg et al., 2006).

Discussion and conclusion

Triggered by environmental constraints and associated regulations that affect their cost function and competitive advantage, established process manufacturing firms continuously need to come up with technological process innovations that allow improved resource productivity of their full-scale manufacturing operations (Skea, 1994; Tidd et al., 2005; Reichstein and Salter, 2006). However, these firms often encounter difficulties to internally develop technological process innovations. By performing the development phase of technological process innovation in external test facilities, firms may overcome these difficulties.

Whereas performing activities in an external location may also be related to the discovery phase (e.g., Hagedoorn, 2002) or the deployment phase (e.g., Strange, 2011), this paper focused on the development phase (e.g., Håkansson, 1987; Macher, 2006) of technological process innovation. It is in this phase that most firms, and in particular established process manufacturing firms, encounter difficulties (e.g., Macher, 2006; Burgers et al., 2008). This is mainly due to the intra-organizational dominance of exploitation pressures that inhibit the internal development of technological process innovation. As performing the development phase in an external test facility represents a large change for firms that are used to conduct the associated activities internally, we focused on the enabling role of new-to-the-firm management activities required in this inter-organizational context. The propositions in this paper regarding these so-called management innovations (e.g., Birkinshaw et al., 2008) have been developed from the perspective of the individual firm (Laage-Hellman, 1987). We have used illustrations from the research context of an external test facility in one of Europe's largest petrochemical complexes in which established process manufacturing firms can develop sustainable process technologies.

Contributions and theoretical implications

The importance of management innovation for enhancing and leveraging technological innovation and in building and sustaining a competitive advantage is increasingly being recognized in the literature (e.g., Damanpour and Aravind, 2012). The role of management innovation in enabling technological (process) innovation in an inter-organizational context, however, has remained largely under-researched. By addressing this research gap, we have contributed in at least two ways to the literature, each with implications for theory.

First, by taking an inter-organizational perspective, we have contributed to an increased understanding of the relationship between management innovation and technological process innovation. We developed propositions on how four separate and context-neutral subsets of new-to-the-firm management activities – i.e., new-to-the-firm management activities associated with: (1) setting objectives; (2) motivating employees; (3) coordinating activities; and (4) decision making (Birkinshaw and Goddard, 2009; Birkinshaw, 2010; Van Den Bosch, 2012) – enable established process manufacturing firms to perform the development phase of technological process innovation in external test facilities. By conducting this phase outside the organizational boundaries, internal difficulties in developing new technological processes can be overcome.

Previous literature has emphasized the importance of realizing both technological and management innovation in order to further organizational goals (Ettlie, 1988; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2006; Schmidt and Rammer, 2007; Damanpour et al., 2009; Battisti and Stoneman, 2010; Evangelista and Vezzani, 2010; Camisón and Villar-López, 2012; Sapprasert and Clausen, 2012). The relationship between both types of innovation, however, is still debated in the literature (Sanidas, 2005; Damanpour and Aravind, 2012). On the one hand, scholars have referred to management innovation as a necessary adaptation to (and hence being triggered by) the introduction of technological innovation (e.g., Evan, 1966; Passmore et al., 1982; Goldhar and Jelinek, 1983). On the other hand, Damanpour and Evan (1984: 392) found that management innovation tends to trigger technological process innovation ‘more readily than the reverse’, suggesting that innovation in a firm's technical system is often driven by innovation in its social system. And, in a related vein, Nelson (1991: 72) notes that technological advance would be limited ‘without development of new ways of organization that can guide and support R&D and enable firms to profit from these investments’. More recently, scholars started emphasizing the need to introduce technological and management innovation combined over time in an orchestrated way – ‘instead of pursuing autonomous strategies of innovation types’ (Damanpour and Aravind, 2012: 448) – in order to capture the full benefits of innovation (Damanpour and Aravind, 2012; Damanpour et al., 2009; Sapprasert and Clausen, 2012).

Hence, as also indicated in Table 3, three perspectives on the relationship between technological innovation and management innovation can be discerned. In the first two perspectives, either technological innovation or management innovation has to be realized (i.e., completed) before the other type of innovation takes place. In the third perspective, technological innovation and management innovation are mutually interdependent for their realization and, as a result, are combined over time in an intertwined way. By discerning three phases of technological process innovation and by focusing on one of these phases – the development phase – from an inter-organizational perspective, this paper illustrates how the processes of two innovation types, i.e., (1) technological process innovation and (2) management innovation, are integrated to enhance the effectiveness of this development phase. This points at a combined effect of these innovation types in order to increase organizational performance. More specifically, management innovation associated with performing the development phase in the inter-organizational context of an external test facility is initially preceded by the discovery of a new technological process element that needs further development and triggered by intra-organizational difficulties to realize this development. In turn, the management innovation precedes the subsequent internal deployment of the externally developed technological process element in the full-production system (and hence enables this realization). Our paper emphasizes that performing part of the technological innovation process outside the organizational boundaries is an important contextual factor of the relationship between technological innovation and management innovation.

| Perspective | Illustrative references |

|---|---|

| 1. The realization (i.e., completion) of technological innovation mainly precedes the realization of management innovation: TI → MI | Evan (1966); Passmore et al. (1982); Goldhar and Jelinek (1983) |

| 2. The realization of management innovation mainly precedes the realization of technological innovation: MI → TI | Damanpour and Evan (1984); Lam (2005); Camisón and Villar-López (2012) |

| 3. Management innovation and technological innovation are mutually interdependent for their realization, (i.e., combined relationship as highlighted in this paper): MI ↔ TI | Ettlie (1988); Damanpour et al. (2009); Damanpour and Aravind (2012) |

A second contribution is that we have extended and advanced the management innovation theory and research by developing propositions on management innovation in an inter-organizational context – i.e., in the context of the inter-organizational development of technological process innovation. As pointed out by Birkinshaw et al. (2008), key factors and actors identified in previous literature have mainly been limited to the institutional conditions and attitudes of major influencer groups that give rise to management innovation within firms (institutional perspective; e.g., Guillén, 1994), suppliers of new ideas – including consultants – and their legitimacy (fashion perspective; e.g., Abrahamson, 1996), organizational culture (cultural perspective; e.g., McCabe, 2002) and the actions of key individuals – including CEOs and their leadership styles (Vaccaro et al., 2012) – within the firm (rational perspective; e.g., Chandler, 1962). Although scholars have recognized the importance of paying attention to a locus of management innovation beyond firm level (Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Tether and Tajar, 2008a; Vaccaro et al., 2012), the current body of management innovation research is focusing primarily on an intrafirm level of analysis (e.g., Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Mol and Birkinshaw, 2010; Damanpour and Aravind, 2012; Vaccaro et al., 2012). By showing that management innovation may also be triggered by performing activities in the inter-organizational context, this paper takes the observation that management innovation seems to emerge ‘on the fringes of the organization rather than in the core’ (Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006: 82) a step further.

The adoption of a focus on the inter-organizational context enables a broader recognition of the role of inter-organizational interactions and the associated external change agents in shaping and influencing the management innovation process. External change agents are perceived in the literature as having influence on the management innovation process mainly due to their role of providing legitimacy and expertise (Ginsberg and Abrahamson, 1991; Birkinshaw and Mol, 2006; Birkinshaw et al., 2008). We suggest that external change agents can also actively trigger new-to-the-firm management activities associated with setting objectives, motivating employees, coordinating activities and making decisions. In that way, also stakeholder dialogues can, as suggested by Ayuso et al. (2006), be a potentially powerful source of management innovation. The inter-organizational level of analysis broadens the group of potential external change agents to include – besides consultants, academics and other so-called specialist knowledge providers (Tether and Tajar, 2008b) currently associated with the Birkinshaw et al. (2008) management innovation process framework – agents active in supplier and customer networks, platforms, consortiums or other alliances.

Managerial implications

Our paper highlights at least three important implications for managers. First, managers of established process manufacturing firms have to recognize to what extent intra-organizational tensions to reconcile pressures for exploration and exploitation (March, 1991) across subsequent phases of technological process innovation require the inter-organizational context to enable technological process innovation, and create new-to-the-firm management activities accordingly. The higher the need to overcome these intra-organizational tensions, the more managers should consider performing the development phase in external test facilities. Established process manufacturing firms are increasingly confronted with the quest for more sustainable process technologies, which often entail long-term, complex, experimental and higher-risk development efforts. As operational managers, rules and regulations in established firms are often slowing down or limiting the extent in which these new process technologies can be developed internally, making use of the inter-organizational context of external test facilities for this objective might be increasingly important.

Second, we have suggested that performing the process technology development phase in external test facilities requires an ambidextrous, entrepreneurial type of project manager that bears responsibility for all related inter-organizational activities. As many of these activities will be new for this project manager, who is used to operate within instead of beyond the organizational boundaries, this will require additional skills (e.g., Cummings, 1991) to be provided by experienced managers. The skills needed in this context deserve to be regarded as highly valuable for technological process innovation in established process manufacturing firms. In a similar vein, Gruber and Niles (1974: 40) point out that the utilization of skilled people should be accompanied by ‘a high level of sophisticated management’ because these people are ‘the major resource in management innovation’.

Third, we have provided managerial insights into how new-to-the-firm management activities associated with setting objectives, motivating employees, coordinating activities and making decisions – which can over time result in valuable managerial capabilities – are required to perform technological process development activities in external test facilities and, in turn, to enable technological process innovation. In line with this, we argue that managers of established firms in process manufacturing and other process industries should not focus exclusively on generating and implementing technological process innovation but on combining these efforts with new-to-the-firm management activities, i.e., management innovation. We suggest that this practice of combining technological process innovation and management innovation will possibly trigger and speed up the much needed innovation in the process industry.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations of this paper, suggesting directions for future research, merit discussion. First, by emphasizing the role of managers within the firm in pursuing new-to-the-firm management activities in an inter-organizational context, our propositions reflect a rational perspective on management innovation (cf. Birkinshaw et al., 2008). Hence, we have focused on the actions and choices of key individuals, i.e., managers, regarding whether and how to manage the development phase of technological process innovation in an external test facility. Future research could also examine how institutional conditions and attitudes of major influencer groups (institutional perspective), suppliers of new ideas and their legitimacy (fashion perspective) and organizational culture (cultural perspective) play a role in this process.

Second, although the new-to-the-firm management activities needed for enabling technological process innovation in an inter-organizational context are associated here with the context of the process manufacturing industry, future research may investigate other process industries in which firms encounter difficulties in enabling technological process innovation, such as firms in the fields of oil and gas as well as service industries. Miles (1994: 252–253) already pointed out that ‘with the growth of producer services, and the externalization of some service functions by firms in other sectors, manufacturing and services are becoming more intertwined’, and noticed that, as a result, innovation in services frequently involves technological innovation. This intertwining of manufacturing and services is also highlighted by Sako (2006), who emphasized that services are increasingly ‘productized’ and products are increasingly ‘servicized’, thereby blurring their traditional distinction. Technological process innovation also includes new elements introduced into an organization's service operation for rendering its services to the clients (Damanpour et al., 2009). To enable such technological process innovation, firms in service industries may also need to consider performing the development phase of innovation in service delivering processes beyond the organizational boundaries (Tether and Tajar, 2008a), requiring new-to-the-firm management activities. To further increase the generalizability of the developed propositions and implications of this paper, future research may also address the effect of, amongst others, top management team support (Smith and Tushman, 2005), firms' market and technological environment (Damanpour and Evan, 1984), their level of capital investment and firm size (Reichstein and Salter, 2006) on the role of management innovation beyond firm level in enabling technological process innovation.

Third, in describing underlying factors that drive firms' decisions or considerations to opt for the development of new process technologies outside the organizational boundaries, this paper focused on intra-organizational tensions to reconcile pressures for exploration and exploitation that prevent timely and effective technological process innovation. However, other factors might also drive managers to consider this option. For instance, in the process manufacturing industry the waiting periods for obtaining a licence to test innovative installations towards industrial scale are often long. This is an external barrier to technological process innovation, residing in the regulatory environment, which challenges firms to look for inter-organizational solutions. Firms using the external test facility as described in the introduction gained access to an umbrella licence from the regional environmental protection agency, strongly reducing the permit procedure duration per pilot. Another driving force for firms to use external test facilities may include benefiting from extending the breadth of knowledge sources ‘to counteract firms’ natural cognitive tendencies to search narrowly along familiar avenues', as pointed out by Leiponen and Helfat (2010: 235). These authors found evidence that the breadth of knowledge sources (both intra- and inter-organizational) positively influences innovation success.

Management innovations that increase this breadth of knowledge sources – such as management innovation associated with performing the development phase of technological process innovation in external test facilities – is therefore intertwined with the realization of technological innovation, pointing towards the combined relationship between management innovation and technological innovation as highlighted in this paper; see also Table 3. Future research may further examine other contextual factors for the interplay between both types of innovation.

Fourth, we discerned discovery, development and deployment as the three phases associated with technological process innovation. Promising new technological process elements discovered by a firm have been assumed to be deployed in the production operations of that same firm, which is in line with the internal focus characteristic of process innovation as suggested by Damanpour and Gopalakrishnan (2001). However, newly discovered and developed technological process elements could also be externally commercialized by selling these new process elements to other firms (Laage-Hellman, 1987; Athaide et al., 1996; Slater and Mohr, 2006). In that case, process innovations turn into new products to be sold. An interesting venue for future research – also requiring a perspective beyond firm-level – is to examine the role of management innovation in fostering the commercialization of technological process innovation.

Fifth, this paper does not address the impact on firm performance of management innovation (e.g., Birkinshaw et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2011) in an inter-organizational context to enable technological process innovation. Future research may investigate how innovations in this way influence interdependencies (both intra- and inter-organizational) and complexity of process innovation and, thereby, are likely to increase performance (Lenox et al., 2010; Rivkin, 2000).

Notwithstanding the discussed limitations, we would argue that the conceptualization of management innovation in an inter-organizational setting advances the management innovation literature, and that this paper contributes to a better understanding of the role of management innovation in enabling technological process innovation.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Port of Rotterdam Authority in funding the PhD research of the first author. They are also grateful for the interviews and discussions held with senior managers of various leading companies and organizations in the Port of Rotterdam.