‘When I can ride my bike, I think, am I at all as sick as they say?’ An exploration of how men with advanced lung cancer form illness perceptions in everyday life

Funding information: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The study received funding from The Danish Occupational Therapist Association.

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to explore how men with advanced lung cancer form perceptions of their illness in everyday life and how this influences perceptions about rehabilitation.

Methods

Constructivist grounded theory principles guided the collection and analysis of data from in-depth interviews with 10 men with advanced lung cancer.

Results

The findings show that the men's illness perception was fluid, contextual and formed by interrelated factors. Engaging in daily activities and maintaining everyday life was a strong influence on their illness perception.

Conclusion

In order to make rehabilitation relevant to men with lung cancer, consideration should be given to how the men's everyday lives may be incorporated into the service provision.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2018 in Denmark, where this study was conducted, lung cancer was the second most common cancer type among men, and the incidence of new lung cancer cases among men was higher than among women (The Danish Cancer Society, 2020). Lung cancer has significant personal consequences. Fatigue, pain and respiratory problems encumber everyday life, and maintaining social relationships is challenging (Petri & Berthelsen, 2015; Polanski et al., 2016; Roulston et al., 2018). It is not uncommon for people with lung cancer to constrain themselves to inactivity and live sedentary lives to avoid worsening the symptoms (The Danish Cancer Society, 2020). To alleviate the consequences of lung cancer, cancer rehabilitation can be essential (Edbrooke et al., 2019; Raunkiær, 2022). In a Danish context, the purpose of rehabilitation is that people achieve the best possible participation, self-determination, mastery and a high degree of self-perceived quality of life as possible in everyday life (Maribo et al., 2022). However, despite the immense challenges experienced by men with lung cancer, their level of participation in rehabilitation remains low.

Studies show that how people perceive themselves, as ill or as healthy, influences their motivation for participating in cancer rehabilitation (Berner & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2017; Ingholt & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2014). Illness perception is connected to how people respond emotionally to their situation, their coping behaviour and their perseverance with treatment (Hoogerwerf et al., 2012; Miceli et al., 2019; Petrie & Weinman, 2006). Research indicates that men and women form different illness perceptions, with men tending to be more optimistic about their illness and situation than women (Edelstein et al., 2012; Hansen et al., 2021; Zawadzka & Domańska, 2020). This implies that gender-specific investigations could be necessary when studying illness perceptions in people with cancer.

For men with cancer, their perceptions of illness, health and how they manage their illness are connected to their sense of masculinity (Stapleton & Pattison, 2015). It can be multifaceted and associated with experiences in everyday life, not necessarily with factors that represent the biomedical perspective of health professionals, such as diet, smoking and exercise (Berner & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2017; Handberg et al., 2014). For example, in the case of men with cancer, being healthy may be associated with the enjoyment of engaging in activities, such as get-togethers and participating in outdoor activities (Berner & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2017).

From a health care perspective, understanding how men with cancer perceive their illness can be a prerequisite for motivating them to participate in cancer rehabilitation (Berner & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2017; Ingholt & Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, 2014). This knowledge may be relevant in developing cancer rehabilitation services that align with the men's needs and wishes. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to explore how men with advanced lung cancer form perceptions of their illness in everyday life and how this influences perceptions about rehabilitation.

In this study, advanced lung cancer is defined as the stage of cancer observed in the tissues of the lungs when the cancer is progressive and presumed incurable (National Cancer Institute, 2021; The American Cancer Society, 2021). In line with Sawyer et al. (2019), illness perception refers to how men with advanced lung cancer experience and develop personal understandings of their illness, how they mentally frame living with it and whether they perceive cancer as manageable or threatening.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design

To explore the process of how men with lung cancer form perceptions of their illness, constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) was chosen as the overall methodology.

2.2 Sampling procedures

Sampling, data collection and analysis went through the procedures of initial sampling and theoretical sampling (Charmaz, 2014). Initial sampling was broadly aimed at exploring how experiences in everyday life influenced the participants' illness perceptions. Participants were recruited using the following criteria: men, 18 years of age or older and considered (by themselves or doctors) to have an advanced stage of lung cancer.

As the analysis progressed, it became necessary to recruit participants with specific characteristics (theoretical sampling) to support the development of codes and categories. For example, by coincidence, the two first participants were living with a partner (either married or in a relationship). The analysis of these interviews indicated that the participants' partners influenced their illness perception. More men with partners were recruited to improve our understanding of the implications of being in a relationship. Men without a partner were also recruited to understand the implications of being single.

Participants were recruited from an outpatient treatment clinic at a Hospital in Region Zealand, Denmark. Eligible patients were given written and oral information about the study. If they agreed to participate, their contact information was passed on to the first author, who established contact. A total number of 10 men were enrolled in the study. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants.

| Pseudonym | Age | Primary diagnosis | Family status | Employment status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tom | 64 | Lung cancer | Married, three adult children | Paramedic (sick leave) |

| Gabriel | 69 | Lung cancer | Married, three adult children | Military background (retired) |

| Dave | 62 | Lung cancer | In a relationship, three adult children | Unskilled work (early retirement) |

| Sam | 63 | Small cell lung cancer | Married, four adult children | Plumber (early retirement) |

| Jerry | 65 | Lung cancer | Married, two adult children | Carpenter (retired) |

| Hans | 63 | Lung cancer | Living alone | Worked with young children (early retirement) |

| Ben | 60 | Small cell lung cancer | Married, two adult children | Freight forwarder (early retirement) |

| Henry | 70 | Small cell lung cancer | Living alone, one adult child | Worked with IT (retired) |

| Dan | 65 | Lung cancer | Married, two adult children | Building constructor (retired) |

| George | 54 | Lung cancer | Living alone, one child living at home | Toolmaker (early retirement) |

2.3 Data collection

Data were collected for a period of 1 year using in-depth interviews (Bryman, 2016). The four phases in the Interview Refinement Protocol Framework were followed rigorously to ensure alignment between the interview guide and the study focus (Castillo-Montoya, 2018). In phase one, a matrix was developed to ensure that the study focus areas were covered and aligned with the interview questions. In phase two, the appropriate order of the interview questions was decided. In phase three, the interview guide was discussed and refined in collaboration with a senior member of the first author's research unit. The interviews were conducted in phase four, continuously adjusting the interview questions to support the ongoing analysis. Interviewing continued until all data were collected. In all, 10 interviews were conducted. Five interviews were conducted in the participants' homes. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, three interviews were conducted using a virtual platform Zoom® and two via phone. The interviews lasted between 36 and 130 min. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4 Data analysis

Data analysis was an iterative process involving coding data, comparing codes and identifying relationships, developing categories, writing memos and raising analytical questions that were answered using incoming data and data already collected.

2.5 Initial coding

Data analysis began when data were collected from the first two participants. The interviews were read through line-by-line to get an overview and a sense of the data. Sentences or paragraphs were coded using the participants' own words, such as ‘questioning the doctor's words’ (Charmaz, 2014).

2.6 Focused coding

When data had been collected and coded from four participants, the codes were compared to identify those that captured essential experiences and the conditions that had shaped the participants' illness perceptions. The following incoming data were coded using these codes while at the same time remaining open to new insights. The codes were continuously compared to identify possible relationships. If relationships between codes seemed plausible and allowed for abstract understandings of the data, they were compiled and considered as categories (Bryant & Charmaz, 2007). For instance, the category ‘The hazy presence of cancer’ consisted of codes related to the participants' reflections about knowing they had cancer but not having symptoms. When data had been collected and analysed from seven participants, a core category resemblance emerged, binding the categories into a whole (Holton, 2007). More data were collected and analysed until all categories, and their relationships seemed fully developed.

2.7 Memo writing

Memo writing composed the text pieces from related codes into cohesive descriptions with a narrative-like structure (Charmaz, 2014). The writing was essential to compiling codes into categories.

2.8 Ethics

In Denmark, only research that entails biological material or pharmacological and hospital equipment testing on humans needs ethical approval (The National Committee on Health Research Ethics, 2022). Accordingly, ethical approval was not required. The study was approved by the university hospital research board. In accordance with The General Data Protection Regulation and National Guidelines, written consent was obtained from participants, and they were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Names have been replaced by pseudonyms to anonymize the data. Data were stored and handled following national guidelines (The Danish Data Protection Agency, 2022).

3 RESULTS

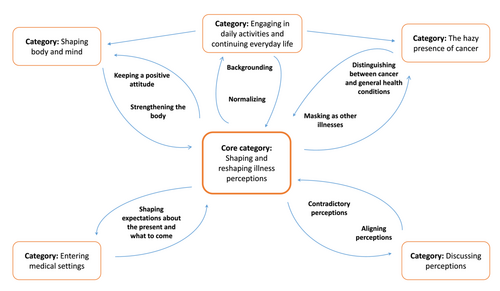

The core category ‘Shaping and reshaping illness perceptions’ emerged as an abstract understanding of the men's illness perceptions. Several factors contributed to the changing and contextual nature of the men's illness perceptions, reflected in five categories and their relationships to the core category. Some categories were connected, revealing the dynamic nature of their illness perception, as illustrated in Figure 1.

3.1 Shaping and reshaping illness perceptions

All the men knew they had life-threatening cancer: a message conveyed to them by doctors and nurses. However, from talking to the men, it became clear that their perceptions of being ill were not static. Rather, their illness perception was continuously shaped and reshaped by the challenges it posed to their daily lives and actions and interactions across contexts. Depending on what they were doing and where they were, their perception of being ill could shift. Notably, the shifting and contextual nature of the men's illness perceptions varied across the group. However, the factors described in the following categories were consequential on all participants' illness perceptions.

3.2 The hazy presence of cancer

I cannot feel it, I cannot see it, and I cannot hear it. It is a strange thing. An actual disease, like a wound on the hand, you can see it, and you can feel it. You tend to forget; you become unaware that you are ill.

The haziness of cancer was connected to the participants' illness perceptions in the following two ways:

Distinguishing between cancer and general health conditions

It is difficult to say because I do not feel it that much. Of course, I get short of breath, but I did that anyway because I am in poor condition.

Masking as other illnesses

Typically, when I got back from East Asia (Business travels), I got a cough from the air conditioning (in airports and business offices). This time it just went on, and eventually, I lost my voice. I had no pain; I could not feel anything. It turned out to be small cell lung cancer.

3.3 Engaging in daily activities and continuing everyday life

On the days I feel well, I cannot stop thinking about whether I am as sick as they (doctors) say I am. I sometimes question that. When I can ride my bike, I think: am I at all as sick as they say I am?

It seemed that some daily activities were more associated with being healthy and not ill compared with others. Many of these daily activities had been a part of the participants' everyday lives before cancer. They entailed some degree of physical activity, like fixing the car, hiking, photography and biking. Other more sedentary activities were associated with illness, resignation and giving up, like lying in bed and watching TV.

Being involved in daily activities and continuing their everyday lives were connected to the participants' illness perceptions in the following two ways:

Backgrounding

I do not think about it (cancer). Quite honestly, I just think about the natural surroundings I am walking in. If I have a good day, I do not think about it as such. If I'm a little out of breath, well, then I just have to take a little break. But I do not think about it.

Some participants would get involved in absorbing activities as an intentional strategy if they became overwhelmed by negative thoughts. To others, like Tom, this just happened as they went on with their daily lives.

Normalising

Because I can walk, stand, run and live my life as I normally do, I feel healthy (not ill). Being healthy is living a normal life.

Ben also described how shocked he was when receiving his diagnosis because he had no symptoms and was living as he usually did, thus emphasising the link between a normal life and not being ill.

3.4 Shaping body and mind

Of course, I am never going to give up. I know that I am going to get through this. I have these ‘soldiers’ (cells combating cancer) inside me, and they will win this war.

The participants' attempts to fight the cancer were connected to their illness perceptions in the following two ways.

Keeping a positive attitude

Only five percent survive lung cancer after five years. I am going to break that statistic because I am me! I am optimistic, so it is not going to happen—a positive attitude is a winner.

To some participants, being able to continue engaging in activities they found meaningful helped them preserve positive thinking about their situation and the time to come.

Strengthening the body

It was a good exercise. It helped me rebuild my strength. I was scrawny at that time. It (relevance of rehabilitation) depends on how frail you are; I do not belong to that group now.

However, most were reluctant or dismissive about rehabilitation services, which they found irrelevant, or said they preferred to exercise independently.

3.5 Entering medical settings

You cannot have a conversation with the doctors without being made aware of how severe your illness is. It is not what you want to hear.

The three months I did not receive treatment were just one long vacation. I had no thoughts about cancer at all.

Being in medical settings influenced the men's illness perceptions in the following way:

3.6 Shaping expectations about the present and what to come

I expect a lot from immunotherapy. The doctors told me that we might be lucky. It (immunotherapy) might prevent my cancer from growing. The doctors have high expectations, well, not high, but reasonable expectations at least. So, I have to hope for the best.

3.7 Discussing perceptions

When I play pool with my friends, we usually drink a couple of beers. This is now bothering her (wife), and she puts pressure on me to drink less. When I ask her, ‘Why?’ she replies, ‘Because you are sick.’

Participants living alone had to rely on themselves, doctors and nurses to make the right decisions about their situation. Their partners influenced the men's illness perceptions in the following two ways.

Aligning perceptions

Your legs feel like jelly, and your whole body is just ‘Aarhh’ (in pain). I just want to throw myself in front of the TV. I have done that many times. But Sophie (wife) is good at kicking me in the butt. ‘Get up!’ she says (laughing). So, I get up and do the things I can.

Contradictory perceptions

My wife manages our diet; lots of cancer-fighting vegetables. She knows all about it because she is a nurse. I did not care about healthy food before cancer, but now I eat a bit of it (reluctantly). If I were living alone, I probably would not eat it. Five hundred grams of vegetables make no difference. The only thing that helps is pure poison (Chemotherapy).

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore how men with advanced lung cancer form perceptions of their illness in everyday life and how this influences perceptions about rehabilitation.

An essential finding was that the men felt a strong connection between engaging in daily activities and maintaining their everyday lives, a sense of normality and being healthy rather than ill. Daily activities became an intermediary between the men's illness and their illness perception. The illness materialised in their minds and became palpable when using their hands and bodies and going about their day. Being ill was not a passive state of being and knowing but rather an active state of doing and engaging oneself.

These findings are supported by other studies. Several studies have similarly demonstrated that continuing daily activities are associated with positive feelings (Ikiugu & Pollard, 2015; Maersk et al., 2019; Peoples et al., 2017; Reeve et al., 2010; Svidén et al., 2010). In the case of people with advanced cancer living at home, Maersk et al. (2019) found that engaging in activities, like vacuuming, fostered positive perceptions of their illness status; they were still capable and active. Adjacent to this, although the men in this study knew they had a life-threatening illness, several said they did not feel sick. La cour et al. (2009) have pointed to the same contradiction and tension in the illness experience among people with advanced cancer. They found that feeling capable was associated with being healthy, paralleled by the notion of being severely ill. Stapleton and Pattison (2015) found that men with advanced cancer associated self-reliance and being in control with normality and their lives before cancer. They also found that changes to their bodies and appearance were perceived as visible markers and representations of their illness (Stapleton & Pattison, 2015). The men in this study did not explicitly mention their bodies but rather what they could do with them. Clearly, the activities encompassed by everyday life are essential to illness perceptions for this group.

To enable men with cancer to participate in everyday activities which they prioritise, it has been recommended that cancer rehabilitation and treatment be specifically designed to accommodate the preferences of the male group to stimulate and reinforce their motivation (Burns & Mahalik, 2007; Handberg et al., 2014; Handberg et al., 2015). To achieve this goal, this study offers insights into how illness could be conceptualised and how men with lung cancer might become motivated to participate in cancer rehabilitation. The findings show that the men's illness perceptions were fluid and contextual and formed by interrelated factors. Their motivation to participate in cancer rehabilitation seemed connected to their perception of cancer as an organism, the growth of which they could inhibit by strengthening their bodies. However, motivation may also be aroused by addressing factors other than physical strength, such as being involved in daily activities. Daily activities perhaps provide a readily accessible setting or language that enables health care professionals to communicate with men about their rehabilitation needs.

4.1 Method discussion

A limitation of this study is the use of a telephone for data collection, which made it challenging to show empathy when participants became emotionally affected. Block and Erskine (2012) also pointed out this. However, the physical distance between participants and researcher, which Zoom® and telephone allowed, made it possible to include participants who would not have participated due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Archibald et al., 2019; Block & Erskine, 2012).

Constructivist grounded theory research quality resides in theoretical saturation, which occurs when all categories and their relationships are defined and explained (Charmaz, 2014). To achieve this, we ended the collection of data when no new insights emerged from the analysis and all analytical questions seemed answered. A limitation of this study could be the relatively low number of participants for a grounded theory study. However, in tune with the underlying assumptions of constructivist grounded theory (Foley et al., 2021) (Charmaz, 2014; Foley et al., 2021), we strove for explanatory depth rather than representativity by rigorously adhering to grounded theory guidelines.

5 CONCLUSION

This study offers insights into how men with advanced lung cancer form illness perceptions in everyday life and how this relates to perceptions about cancer rehabilitation. The findings from this study show that the men's illness perception was fluid and contextual and formed by interrelated factors. Of these factors, engaging in daily activities and upholding everyday life influenced their illness perception. Therefore, it is worth considering how men's everyday lives could be a more integrated part of cancer rehabilitation. Exploring how cancer rehabilitation could interplay with men's illness perception and its connection to their everyday lives, as outlined in this study, could be a topic for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank the participants who gave us valuable time and shared their experiences. Without their contribution, the present study would not have been possible. We want to thank Jeanette Praestegaard, DrMedSc, MSc, PT, for her encouragement and input. Special thanks go to the nurses from the Department of Clinical Oncology and Palliative Care Units at Zealand University Hospital for helping us recruit participants for the study. Finally, we thank our funding organisation, The Danish Occupational Therapy Association.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The principal author Jesper Larsen Maersk declares no conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship and publication of this article. I, Line Lindahl-Jacobsen, declare no conflict of interest regarding the manuscript. I, Elizabeth Rosted, declare no conflict of interest regarding the manuscript.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.