Patient experiences and views on pharmaceutical care during adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer: A qualitative study

Funding information: This work was supported by the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie [KNMP]).

Abstract

Objective

The use of adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) after primary treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer reduces the risk of recurrence and mortality. However, non-adherence is still common. Limited consideration has been given to how users deal with AET and the role of pharmaceutical care. Therefore, this study aims to obtain insight into the needs and wishes of women using AET regarding pharmaceutical care and eHealth.

Methods

This is a qualitative explorative study comprising semi-structured interviews (n = 16) and a focus group (n = 5) among women who use or used AET after primary early-stage breast cancer (EBC) treatment using a thematic analysis approach.

Results

Three themes emerged from the interviews and focus group: (1) experiences with AET use, (2) experiences with provided information and (3) needs and wishes regarding pharmaceutical care. Most women were highly motivated to use AET and indicated to have received useful information on AET. However, many expressed a strong need for more elaborate tailored and timely provided information on AET. They acknowledged the accessibility of pharmacists but reported that currently, pharmacists are hardly involved in AET care. Several women considered eHealth useful to obtain counselling and reliable information.

Conclusion

Women need more comprehensive information and follow-up in primary setting after initial cancer treatments. A more elaborate role for the pharmacy and eHealth/mHealth, especially with regard to counselling on side effects and side effect management, could potentially improve pharmaceutical care.

1 INTRODUCTION

Between 4% and 30% of women with hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer who completed primary treatment of early-stage breast cancer (EBC) do not initiate the follow-up long-term adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) (Berkowitz et al., 2021; Kroenke et al., 2018; Neugut et al., 2012; O'Neill et al., 2017), and 15–43% are non-adherent (i.e., do not take medication as prescribed) (Berkowitz et al., 2021; Cavazza et al., 2020; Font et al., 2019; Lailler et al., 2021; Lambert-Côté et al., 2020; Makubate et al., 2013; Mislang et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2012). AET is used in patients with oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive EBC for at least 5 years in order to prevent recurrence and reduce the mortality (Cardoso et al., 2019; Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group, 2011) and comprises the (sequential) use of the selective ER modulator (SERM) tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) like anastrozole, exemestane and letrozole (Burstein et al., 2019; Cardoso et al., 2019; Parisi et al., 2020). AET non-adherence has been associated with increased risks of recurrence and mortality (Barron et al., 2013; Chirgwin et al., 2016; Font et al., 2019; Hershman et al., 2011; Inotai et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Makubate et al., 2013; Mislang et al., 2017; Winn & Dusetzina, 2016) and higher healthcare costs resulting from more physician visits, increased hospitalisation rates and longer hospital stays (McCowan et al., 2013; Mislang et al., 2017). Several circumstances may contribute to AET non-adherence, such as a lack of accurate information on AET efficacy, low social support, inadequate communication and (decisional) support from healthcare professionals (HCPs), fear or burden of AET side effects, including inadequate management of AET side effects, the impact on quality of life and continuity of follow-up care (Brett, Boulton, Fenlon, et al., 2018; Clancy et al., 2020; Harrow et al., 2014; Humphries et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2020; Milata et al., 2018; Mislang et al., 2017; Moon et al., 2017; Paranjpe et al., 2019). Additionally, the period from hospital care to home, where women have to start AET treatment, could be an overwhelming period, since there is less hospital care and women need to take on a greater level of responsibility for their own care. At home, they have to recover mentally and physically from the primary breast cancer treatments and process all information they have been provided with. This may increase the risk of non-adherence (AlOmeir et al., 2020).

In order to improve AET adherence, several interventions have been designed to support women taking AET and promoting its daily use through regular calls or reminders (Chan et al., 2020; Hadji et al., 2013; Markopoulos et al., 2015; Moon et al., 2017; Wagner et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2012). However, these studies report conflicting results since they were mainly aimed at enhancing patients knowledge and improving the relationship between patients and HCPs (Clancy et al., 2020; Ekinci et al., 2018; Finitsis et al., 2019; Kroenke et al., 2018; Lambert et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2017; Rosenberg et al., 2020). Limited consideration has been given to users' experience and challenges with AET and pharmaceutical care (Humphries et al., 2018; Rosenberg et al., 2020) defined as the pharmacist's contribution to the care of individuals in order to optimise medicine use and improve health outcomes (Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe [PCNE], 2010–2022). The recent systematic review of Rosenberg et al. (2020) shows that pharmacist-led interventions show promising effects in order to improve adherence to oral anti-cancer agents. These improvements are probably due to the frequent encounters of pharmacists with women using AET and their ability to detect non-adherence and therefore optimise the medication (Humphries et al., 2018; Rosenberg et al., 2020). However, studies on women's experiences and perspectives on pharmaceutical care regarding AET are rare. Consequently, it is unknown to which extent they receive pharmaceutical care and information on AET in different settings, or other sources, like eHealth applications. Therefore, this study aims to obtain insight into the needs and wishes of women using AET regarding pharmaceutical care and explore their views on the role of eHealth in AET counselling.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

This qualitative explorative study made use of semi-structured face-to-face interviews and a focus group meeting with women using AET and those who had previously used AET. Interviews were conducted to obtain first-hand information on their views regarding AET and pharmaceutical care. The focus group meeting was conducted to validate and deepen the understanding of the interview results. The Medical Ethics Committee (METC) has reviewed the protocol and has confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) does not apply to the present study. This study has been conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (version 64, October 2013) and other Dutch laws and regulations, that is, the law for the protection of personal information, the law on medical treatment agreement and the code of conduct health research. Written informed consent to audiotape the interviews/focus group meetings and use of information and quotes from these recordings were obtained from all the participants prior to the data collection. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and could be terminated at any time. Names and other identifiers were changed to protect the participant's privacy.

2.2 Procedure and study population

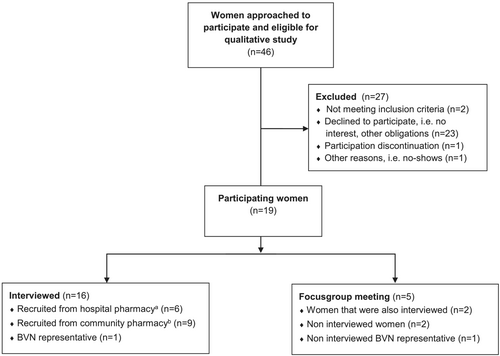

Women with HR-positive breast cancer aged 18 years or older who filled at least one subscription for AET (tamoxifen, anastrozole, letrozole or exemestane) over the last 12-month period were eligible. Women were recruited from February to July 2017, through two Dutch pharmacies in two provinces: a community pharmacy and a hospital outpatient pharmacy. A purposive sample of women was obtained based on their age, type, duration and adherence of treatment. Women without primary EBC treatment were excluded. Women fulfilling the inclusion criteria were extracted by the pharmacists from each pharmacy's database and recruited to participate by phone. Interviews were conducted until no new themes emerged from three consecutive interviews. In total, 46 women were invited to participate of which 19 participated in the study. Twenty-three women declined to take part because they had no interest (e.g., were busy and wanted to get their life back on track) or had other obligations (e.g., work, appointments and holiday). Four women were excluded due to no primary EBC treatment (n = 2), participation discontinuation (n = 1) and no shows (n = 1). In total, 16 semi-structured interviews were conducted, including one woman using AET and representing the Dutch breast cancer patient association (Borstkankervereniging Nederland [BVN]), to further highlight the patient perspective. Five women participated in the focus group meeting, of whom two were also interviewed, two non-interviewed and one non-interviewed BVN representative (Figure 1). Interviews took place between March and June 2017 and the focus group meeting in July 2017. Participants included women diagnosed with EBC between 1999 and 2016, irrespective of discovery by screening or symptoms.

2.3 Interviews and focus group meeting

Semi-structured interviews were conducted on the basis of an interview guide (Table 1), which was created using Qualitative Methods for Health Research by Green and Thorogood (2013). The interview guide consists of three main topics: (1) experiences with the treatment trajectory, (2) experiences with AET and adherence to AET and (3) experiences and women's needs and wishes regarding patient care and specifically pharmaceutical care regarding AET. Women were given the opportunity to discuss subjects outside the topic list. Interview questions were revised iteratively within the research team (SEdH, VNMFT, JGH and MJW). Interviews were conducted by the researcher (VNMFT) in collaboration with an expert on qualitative research (MJW). Interviews took place at the participant's home (n = 8) or the consulting rooms of the pharmacies (n = 8). Prior to each interview, the purpose of the interview was explained, participants were asked permission for audiotaping and informed consent was obtained. The average duration of the interviews was 44 min (range 30–65 min). All interviews were transcribed verbatim.

| Check-in |

|---|

|

| Interview—Start recording |

|---|

|

Information on the women's personal background concerning experiences with the treatment trajectory

Experiences on adjuvant endocrine therapy and therapy adherence

Experiences on patient care and pharmaceutical care regarding AET

|

| Sociodemographics |

|---|

|

- Note: Green and Thorogood's Qualitative Methods for Health Research (2013) was used to create this interview guide.

The focus group meeting was conducted after the interviews to further explore possible ways to improve AET care as well as women's preferences regarding AET information provision and pharmaceutical care. The focus group meeting was moderated by the principal investigator (JGH), who had experience with moderating focus group meetings, and observed by two researchers (SEdH and VNMFT). The focus group meeting lasted 1 h and 45 min and was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4 Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this study.

3 DATA ANALYSIS

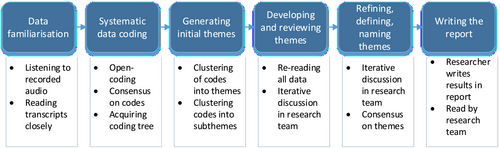

A thematic analysis inductive approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) has been used to analyse the interview transcripts (Figure 2). Transcripts were subsequently read closely, and the first three interviews were independently open coded by two researchers (SEdH and VNMFT). The codes were then discussed with the research team (SEdH, VNMFT, JGH and MJW), and consensus on the codes was reached. All codes were subsequently clustered into an initial coding tree. Remaining data were then open coded to find new codes. These codes were then clustered into themes and subthemes (at semantic level). All data were re-read, and iterative discussion between researchers on codes, themes and subthemes took place. Transcripts were coded using the ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software package version 7.5.16. The study is reported in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines (O'Brien et al., 2014) (Table S1).

4 RESULTS

Characteristics are shown in Table 2. Nineteen women aged 48–83 years (mean 61.6 years) participated. EBC was diagnosed between 1999 and 2016. Whether they had discovered breast cancer themselves or it was diagnosed as the result of a screening programme, all women felt that diagnosis came as a shock. Immediately thereafter, they were informed about primary EBC treatment options and scheduling. Many women described the diagnosis and the subsequent period of various primary treatment modalities as a difficult time as it was intense with frequent hospital visits. Women had undergone different primary treatments, the order of which was also different: All women underwent surgery, 13 women as initial treatment. Five women underwent chemotherapy as initial treatment, and one woman started with neoadjuvant ET. Women had various AET modalities, which generally began after having finished most of the primary treatment: 17 women (89%) started with tamoxifen, of whom 11 later switched to an AI. Some also had a second (n = 5) or third (n = 3) switch. One woman discontinued treatment in the fourth year because of side effects. Another decided not to start treatment after a first diagnosis of breast cancer, but did start AET after recurrence. The remaining women were still on AET; some recently started (<6 months), some were using it for some years and others almost finished the recommended treatment period.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range), median | 61.6 (48–83), 58 |

| Age group, n (%) | |

| <50 years | 2 (11) |

| ≥50 to <60 years | 8 (42) |

| ≥60 to <70 years | 4 (21) |

| ≥70 to <80 years | 4 (21) |

| ≥80 years | 1 (5) |

| Living situation, n (%) | |

| Together | 15 (79) |

| Alone | 4 (21) |

| Education, n (%)a | |

| Secondary | 8 (42) |

| Higher | 8 (42) |

| Unknown | 3 (16) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Employed/self-employed | 7 (37) |

| Unemployed | 4 (21) |

| Retired | 5 (26) |

| Unknown | 3 (16) |

| First diagnosis of cancer, n (%) | |

| Yes | 15 (79) |

| No | 4 (21) |

| Treatment received, n (%) | |

| Surgery | 19 (100) |

| Chemotherapy | 13 (68) |

| Radiation therapy | 16 (84) |

| Ovary removal | 1 (5) |

| Immunotherapy | 2 (10.5) |

| Initial treatment with AET, n (%)b | |

| Tamoxifen | 17 (89) |

| Anastrozole | 1 (5) |

| Letrozole | 1 (5) |

| Exemestane | 0 (0) |

| Current treatment with AET, n (%)c | |

| Tamoxifen | 8 (42) |

| Anastrozole | 6 (32) |

| Letrozole | 2 (11) |

| Exemestane | 2 (11) |

| None (discontinued) | 1 (5) |

| Time on AET, n (%) | |

| <3 years | 7 (37) |

| 3–5 years | 8 (42) |

| >5 years | 2 (10.5) |

| Discontinued after 4 years | 1 (5) |

| Recommended years to take AET, n (%) | |

| 5 years | 8 (42) |

| 5–10 years | 10 (53) |

| >10 years—lifelong | 1 (5) |

- a Secondary education: pre-vocational, senior general or pre-university; higher education: higher professional or university.

- b The first type of AET women received after or during active treatment.

- c Type of AET women were currently using.

Findings from the interviews and focus group meeting will be discussed through three themes: experiences with AET use (e.g., what were women's reasons to initiate, continue or discontinue AET), experiences with provided information (e.g., which information did women receive on AET, from whom, where and when), and needs and wishes regarding pharmaceutical care (e.g., what are women's preferences concerning pharmaceutical care, what changes would they like to see, which HCPs do they want to be involved in certain areas of expertise and what are their views on eHealth).

4.1 Theme: Experiences with AET use

4.1.1 Subtheme: Initiating treatment with AET

When treatment starts you have a chat with your doctor. She tells you that if you correctly use AET then there is a high chance of survival. If you do not, then there is a good chance that there will be a recurrence with all its negative consequences. So that's then what you are going to do, especially because you already have sustained chemo. (Interviewed woman CP07)

I just do not want the disease to return, so I'll do everything to prevent that. (Interviewed woman CP09)

Last year in [month], at the check-up my doctor said that maybe we should stop treatment with letrozole (…). Well, yes, to just stop this treatment, that scares me. (Interviewed woman HP01 on discontinuing AET at the end of her recommended treatment period)

Yeah, you know, I really do not know anything about it and if the physician tells me it's better, then I'll give it a try. (…) I always think, and my husband does so as well, the physician has studied for it so he knows best. (Interviewed woman CP12)

You do not have a choice, you know. It's hormonal (…) so you'll get a pill that kills the hormones. That's like one plus one equals two, you do not think about it, you just want to live. You want to carry on. (Interviewed woman HP04)

A physician would always recommend to continue AET (…), but I have noticed that the support group is much more understanding that side effects are sometimes so bad that you cannot keep it up. (Interviewed woman BVN16)

4.1.2 Subtheme: Not initiating treatment with AET

USA study data showed that I had 85% chance not to get it back. Then I thought I will take that 15% risk. […] Because if you are going to take those hormone tablets, then you will enter a kind of second menopause phase. I thought that was going to be too hard, but then the breast cancer recurred and metastasized six years later […] I was like, okay I have to be sensible now and just take it. (Interviewed woman HP11)

4.1.3 Subtheme: AET non-adherence

And I think, basically it is just one pill a day and I am in favor of that. Because otherwise if I discontinue, in spite of the side effects I experience with my hands, and who knows whether that passes or not, […] I feel like that's like playing Russian roulette with my life. (Interviewed woman CP02)

I take a black marker and write the days of the weeks on the strips […] Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday […] This way I know exactly that I have taken my dose. (Interviewed woman HP03)

4.2 Theme: Experiences with provided information

4.2.1 Subtheme: Information by different HCPs

All participants reported that they had been provided some information on AET prior to initiation. Primarily, it was provided by their physicians at the hospital. Additional information was usually given by breast cancer care nurses, the community or outpatient pharmacies or occasionally their general practitioners (GPs). Information was often given face to face during consultation, and most women were given an information leaflet.

Many participants reported that the information they received generally included information on the mechanism of action of AET, their survival rate if they took AET for the recommended period of time and the possibility of switching from one AET to another. For most women, this information was provided at the start of primary EBC treatment by their physician. Breast cancer nurses generally elaborated more on side effects and the switching of medication. Some women also received additional information on how to use AET and its possible side effects from their pharmacist or the pharmacy assistants. However, most women indicated that currently, they are hardly involved in providing information on the use of AET.

4.2.2 Subtheme: Timing and load of information

When you get the diagnosis and primary treatment, then you are in an emotional rollercoaster. You are thinking about your family: ‘I do not want to die and I have a husband and two kids’. That's the first thing you think about. But then you really do not hear that your survival rate is 97% and all the things they tell about hormonal therapy. That's then beyond me and that is why they hand you their folder, but then you find out it does not give you all the answers. (Interviewed woman HP03)

If you have questions -and I've done that myself- you are going to search for anastrozole side effects and then you will get all kinds of info. But much of that information raises more questions than it provides answers. (Interviewed woman HP04)

4.3 Theme: Views on how to optimise AET care with regard to pharmaceutical care

4.3.1 Subtheme: Proactive and personalised care

The doctor will not inform you on all side effects, (…) I understand that, but on the other hand, I want to know what is normal, but most of all, and this is what I really miss, ‘what can you do to deal your side effects?’ (…) On support groups I see about 6 or 7 posts every day on side effects; people that seek recognition and how to deal with side effects … That is something that is very important among breast cancer patients (…) and I think it is striking that it really takes over a task, that also should partly be carried out by doctors and pharmacists. (Interviewed woman BVN16)

It [surgery] happened in [month]. And surgery was complete, and then everyone [HCPs in the hospital] is done with you, because, yes, I did not have to be irradiated afterwards. So that was the good news, but the bad news was that no one looked after you anymore. Whilst I did expect that, because that's when the whole process [with AET] starts. First, all those months you are completely absorbed by your chemo and all other things that come with it. And then there was just nothing anymore. That's why I fell into an incredibly large void. (Interviewed woman CP02)

4.3.2 Subtheme: Role of the pharmacy

I think it is nice for patients that they [pharmacists] are easily approachable. Because sometimes there are things that you worry about, that can easily be explained by a pharmacist. It would only take a few minutes. Then you do not have to make an appointment with your oncologist, who is already very busy. (Interviewed woman HP11)

I would like some kind of interview, initiated by the pharmacist, like I have for my asthma. Once a year I get an interview where they ask how I am doing with using my medicines. I would like such an interview for AET, because I have so much more problems and side effects with it. (Woman CP19 during focus group meeting)

You really do not go into detail that you have cancer, when there's a line behind you. (Woman CP18 during the focus group meeting)

4.3.3 Subtheme: Role of different HCPs

Foremost we felt that when you start taking those pills, that you are let down somewhat, and that there's no one watching you anymore. And so we would very much like, particularly regarding AET use and its side effects, that there would be an interview with the pharmacist in the first place, because that's your main contact after you have had all these treatments. (Women BVN17, CP07 and CP19 during the focus group meeting, after they had discussed this subject in groups of three)

Well, at the [clinic] they have explained it very well, so yes, I don't need to hear it from the pharmacy again […]. But then I think that there should just be much more collaboration between the GP, the specialist and the pharmacy. (Interviewed woman CP08)

4.3.4 Subtheme: Role of eHealth

Some participants considered eHealth applications (website, mobile phone or both) as useful tools to support women using AET. However, not all women would use eHealth as they did not or hardly used the internet. Women who thought eHealth might be useful to enhance AET pharmaceutical care had a slight preference for a mobile application, because they felt it would be more personal than a website. They also suggested an interactive application where all relevant information is available, because at present, there are so many websites and information sources that it can become overwhelming. Moreover, they found it increasingly difficult to distinguish reliable information from incorrect and misleading information. They also expressed a need for a feature that facilitates interaction between them and HCPs and them and other cancer survivors. Features considered most important have been presented in Box 1.

Box 1. Needs and wishes of women using AET regarding eHealth applications

| Features | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Reliable and clear information on AET in general |

One place where all basic, relevant information is available and constantly updated. In particular:

|

| Reliable and clear information on specific topics |

|

| Interaction between HCPs and patients | Forum, email options, chat function with both HCPs and other breast cancer survivors |

| Push messages | In case of new developments, facts and messages |

| Reminders (in applications) | To prevent forgetting |

| Diary (in applications) | To keep note how it is going |

5 DISCUSSION

Findings from this qualitative study shed light on certain needs and wishes regarding the supportive care for women using AET after primary EBC treatment and specific pharmaceutical care for AET users including the use of eHealth applications.

5.1 Experiences with AET use and care

Most women used AET as prescribed and had not hesitated to initiate AET. Despite discomfort caused by AET side effects, most women were highly motivated to use AET until the end of the recommended treatment period. As observed in several other studies on AET adherence (AlOmeir et al., 2020; Clancy et al., 2020; Harrow et al., 2014; Humphries et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2020), nearly all women expressed that they felt obligated to use AET or had realised that using AET would be the most appropriate way to increase their chance of surviving breast cancer. They believe that AET was necessary often led to the feeling to have no other choice or a fear of not surviving the disease without using AET (AlOmeir et al., 2020; Clancy et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2020). The incorrect use of AET other than forgetting to take a dose, as well as the (temporary) discontinuation of AET, was mainly caused by the occurrence of side effects (Berkowitz et al., 2021; Clancy et al., 2020; Font et al., 2019; Harrow et al., 2014; Humphries et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2020; Lailler et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2018; Lambert-Côté et al., 2020; Milata et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2012; Paranjpe et al., 2019; Sella & Chodick, 2020). Professional support by HCP as well as support from family members, friends and fellow AET users was experienced as a strong incentive to continue AET (Cavazza et al., 2020; Clancy et al., 2020; Humphries et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2020; Kroenke et al., 2018; Milata et al., 2018).

5.2 Needs and wishes regarding pharmaceutical care

Women indicated that by emphasising EBC survival rates and the risk of disease recurrence, education about AET was focused primarily on the necessity to use AET over the recommended period of time, and little attention had been paid to counselling when they were back at home, especially with regard to possible AET side effects, their effect on their quality of life and side effect management. Thereby, information was not always timely provided or tailored to their needs. As the result, the women felt insufficiently educated, which led them to search for additional information and support, especially on the internet. However, they expressed that it was difficult to obtain adequate information from reliable sources. Therefore, women opted for a more patient-tailored approach in information provision that is provided through a collaboration of HCPs. They emphasised that counselling should take place on a continuous basis, especially during transition of care (i.e., from the hospital setting to the home setting) and that the timing of the information provision should be better tuned to their mental state. Studies show that adopting patient-centred approach structured in the form of a (multidisciplinary) monitoring and support programme that covers the entire period of prescribed AET may increase adherence (Brett, Boulton, Fenlon, et al., 2018; Clancy et al., 2020; Finitsis et al., 2019; Harrow et al., 2014; Humphries et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2020; Kroenke et al., 2018; Milata et al., 2018; Paranjpe et al., 2019), whereas this study shows that it also supports the specific needs and wishes of patients. Suggesting that embedding AET users in a tailored multidisciplinary care structure during the transition from primary EBC treatment to secondary AET may empower these women for the upcoming use of long-term AET and provide them with the knowledge, skills and confidence needed to cope with the discomfort, stress and uncertainty brought about by AET side effects. This particular approach could prevent that all information about AET is provided at once or at the wrong time, and more attention can be given to counselling when women are back at home, tailored to the woman's needs.

5.3 Role of the pharmacy

Many women indicated that pharmacies could play an additional role in the abovementioned tailored AET care, since the pharmacy is easily accessible. They were indifferent whether the hospital outpatient pharmacy or the community pharmacy should provide them with information and whether a pharmacist or pharmacy technician counselled them, as long as it was someone with enough knowledge of AET and that they could talk about it in privacy. Studies show that since AET is mostly dispensed by community pharmacies at regular intervals and the pharmacy's personnel are low-threshold and easily accessible HCPs, pharmacies could play a larger role counselling of women who have to initiate AET or are using it (Brett, Boulton, Fenlon, et al., 2018; Harrow et al., 2014; Humphries et al., 2018; Labonté et al., 2020; Paranjpe et al., 2019; Rosenberg et al., 2020). Within a tailored multidisciplinary AET care programme, based on expertise and trust, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians could focus on the provision of information about AET, the safe use of AET, the monitoring and supporting of AET adherence (Humphries et al., 2018; Rosenberg et al., 2020) and AET side effects and their management to improve pharmaceutical care for women using AET (AlOmeir et al., 2020; Berkowitz et al., 2021; Clancy et al., 2020; Humphries et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2020; Labonté et al., 2020; Lambert et al., 2018; Milata et al., 2018; Paranjpe et al., 2019).

5.4 Use of eHealth/mHealth

Several women indicated that internet (eHealth) or mobile accessible communication-based healthcare (mHealth) applications could be a suitable tool for the provision of information on AET and AET counselling. They indicated that eHealth/mHealth could enable them to quickly get information about medicines, connect them with HCPs and have their questions answered quickly. Studies show that eHealth/mHealth could facilitate and improve communication between AET users and their various HCPs by enabling direct (face-to-face) contact outside of regular clinic visits. Additionally, it could be used to record AET side effects and submit them to their HCP for evaluation and feedback at any time. This continuous monitoring of side effects and their severity could make AET side effect management much more effective, which in turn may reduce the risk of non-adherence. Furthermore, unintentional non-adherence (i.e., forgetting) can be tackled by means as keeping electronic diaries or reminders. Other functions such as providing access to reliable information on the internet and ways to communicate with fellow AET users and offering options to plan, register and/or report dietary intake, distress, mood (changes) and physical exercise could also support AET users and promote their self-efficacy (Brett, Boulton, & Watson, 2018; Krok-Schoen et al., 2019; Paladino et al., 2019).

6 STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The qualitative methods used in this study provided rich and more detailed information about how AET is perceived by women using AET and on opportunities to improve AET care, particularly with regard to pharmaceutical care. A strength of the study is that all women had access to low-threshold EBC care. As with all qualitative studies, the small size of the sample that comprised predominantly well-educated, mostly adherent, Caucasian women with presumably mostly non-metastatic EBC mean that the results may not be generalisable to a wider population. However, the women who participated were diverse with respect to age, medication and societal status and recruited in both community and outpatient pharmacies in two different provinces. Some participants were diagnosed and had started AET several years ago. They may have experienced recall bias when reflecting on the information they had received about AET at that time. This study was conducted before the COVID-19 outbreak. It should be recognised that due to COVID-19, currently more consultations are performed digitally, which may have influenced current perceptions of breast cancer pharmaceutical care. Furthermore, interviews and the focus group discussion were conducted in Dutch and later translated into English. This was carefully assessed and discussed with the research team. Nonetheless, the current research design provides depth and insight that may not have been identified by other methods.

7 CONCLUSION

There is a clear need for more comprehensive, patient-tailored information on AET and more intensive follow-up in primary setting for women using AET, particularly, with regard to patient-tailored information provision on AET side effects and side effect management and its safe use in combination with other medicines and food. Pharmacists were acknowledged as easily accessible experts in the field of medicines and were said to be well positioned to play an important and proactive role in AET care, especially in the provision of information about AET, its safe use together with other medicines and food, AET side effects and their management, and in the monitoring of AET adherence and finding appropriate ways to support adherence. EHealth/mHealth was viewed to be promising to enable direct communication between AET users and their HCPs and as an access to reliable information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to all the participating women for sharing their personal stories, experiences and insights. We thank other research personnel Abigail Andrews, Dill Bamarni, Annemijne van den Berg, Soraya En-nasery, Astrid Kramer and Beatrix Vogelaar for their help. Special thanks to Rob Linde and Bart Pouls for their help and comments in the preparation of this manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

HUMAN STUDIES AND SUBJECTS

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to the data collection, and participants were informed that participation was voluntary and could be terminated at any time.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No additional data are available.