AI Enabled Airline Cabin Services: AI Augmented Services for Emotional Values. Service Design for High-Touch Solutions and Service Quality

Abstract

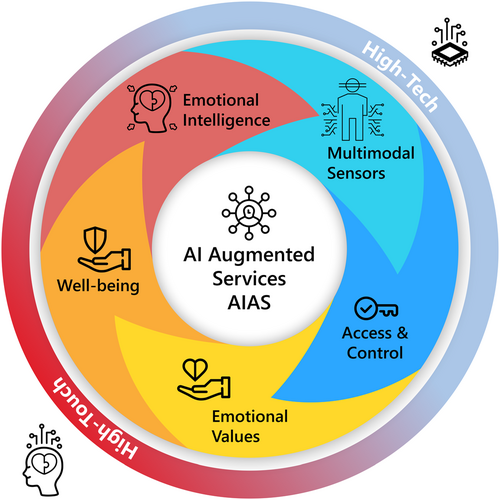

This paper highlights the significance of emotional values within digital services during the airline cabin experience. Currently, emotional engagement with front-line AI interactions, such as AI assistants, lacks trust. Thus, the role of AI must be reimagined to better integrate the human factor into the service experience through things like high-touch in order to create trust and improve the perception of cabin service quality. Service design is a human-centric approach to service creation in which the user is typically made the main subject of the service research; the service process (service interaction) then co-creates values alongside the service provider. The major concept discussed here is AI Augmented Services (AIAS), which turn high-tech capabilities into high-touch “human centric” services that can offer access, control, and well-being to the user, all of which are key components in the establishment of trust. Airline future services can then implement this study for the purpose of detecting human emotions, co-creating emotional values, and promoting emotional intelligence through the AIAS interactive communication channels, thereby transforming high-tech capabilities into high-touch opportunities. The methodological approach began by determining a benchmark for the state-of-the-art AI technology in transport and conducting a set of expert interviews. Notably, the possible materialisation and challenges of AIAS high-touch cabin services are also discussed here. This article can be considered to be a first step toward a service design in which opportunities are discussed with the goal of “discovering” possible AI solutions. Consecutive stages will be presented in future articles in which the concepts introduced here will be further defined and developed.

Introduction

In most services, emotional values are vital to the long-term survival of the brand. The more emotional values a service can provide, the more likely it is that the brand's general perceived value will increase (Almquist, 2016, p. 6). This is not to say that other values, such as those geared toward functionality, are not as important. The idea is that a service with a combination of various value elements is more likely to be perceived with satisfaction. However, emotional values have the most significant effect on the perceived quality of the brand image, especially when these values are being created during the service itself as, “functional dimensions of the service or service consumption,” (Grönroos, 1984). Values that are co-created throughout this period are referred to as “values-in-use,” (Grönroos, 2008). Such generated values are the most significant asset that a company can create; they are the front line of its brand image. Hence, AI enabled services must first demonstrate their effectiveness in the facilitation of value-in-use, whether functional or otherwise. AI becomes most significant to a service when it can co-create emotional values like access to personalised solutions, well-being, therapeutic values, and, consequently, emotional intelligence. The role of AI in services has generally been viewed as “high-tech”; this category includes technologies that provide functional solutions that simplify tasks and save money and time. Even so, AI has the potential to significantly impact service quality when it is designed to provide emotional values. When the customer is provided with personalised interactions that generate emotional value-in-use, the high-tech capabilities of AI become “humanised” and can then be referred to as “high-touch” (Interview, 3; Miettinen, 2014). In sum, AI can positively affect perceived service quality when its goal is to create a high-touch experience.

Morelli (2002) discussed how design can explain the elements of convergence by uniting several social and technological factors, including, “social, technological, and cultural frames of the actors participating in the development of the system,” and, “technological knowledge embedded in the artifacts used for the service.” As a method, service design addresses the overall service experience through increased understanding of customer behaviours and needs as well as the service journey and its significant touchpoints. Understanding these factors can lead to the design of more human-centred AI Augmented Services (AIAS). Simply put, design and service design can facilitate the development of technologically enabled systems that are grounded in a cultural context. Notably, there have been few papers (e.g., Leondini & De Angelis, 2018; Jylkäs & Borek, 2019) that have discussed service design or design thinking in the context of AI development. The idea of service design or design thinking in this context is to create a holistic, user-friendly, frictionless, and inclusive service solution with the help of AI technology (Weller, 2019).

This paper examines different layers at which technology could empower the customer via a human-centric service process. High-touch experiences can be provided through AIAS when the AI is capable of providing appropriately calculated choices to the customer. An AIAS, then, is a semi-automated concept system that relies on both AI and human interactions to learn more about the user. Human-machine interactions (HMI) have the potential to lead the user toward emotional intelligence through self-awareness. The major focus of this study in particular lies on how technology adds wellness and consumer “control” to the cabin-experience by providing the human touch needed for the customer to co-create emotional values whilst augmenting the capabilities of the cabin crew. The process of AIAS starts with gathering data from multiple resources through the cabin experience (CABX) service process. This data is then instantaneously analysed by AI and further evaluated by the user before any decision is made, meaning that the user is aware of the AI engagement but still has full control over the decision-making process. The AIAS system process (Jylkäs, Äijälä, Vuorikari, Rajab, 2018) highlights the user's emotional state, addresses emotional stressors, alleviates past service failure (Vázquez-Casielles, 2007) and, consequently, co-creates emotional values. Note that the term “user” here can refer to either customers or cabin crew, i.e., front line employees (FLEs). As a result, the following questions apply: 1- How can AIAS provide emotional values to the customers and augment employees' capabilities? 2- How do AIAS affect service quality?

AI services consist of both seen and unseen calculations (e.g., Stickdorn, 2018, p. 55). On the service backend, AI functions behind the visual perspective of the customer, in the form of algorithms that prioritise critical attention based on the user's machine learning process, for example. On the frontend AI may be in direct physical or virtual interaction with the user, such as through natural language processing and human-machine dialogues (Jylkäs, 2020). In this paper, we consider AI as an equal actor in a three-way relationship that involves the cabin crew (live human agent), the customer, and the AI agent (Jylkäs, Äijälä, Vuorikari, & Rajab, 2018). This inclusive relationship helps the user to make better decisions in real-time and offers some CABX control, which is what formulates the foundation of the AIAS system.

The following chapters consist of three major parts. Firstly, the background section discusses literature that elaborates on concepts of service marketing and well-being. In four subheadings, the background chapter highlights a service process designed to maximise emotional benefits like self-awareness and emotional intelligence. The methodology section includes in-depth interviews with four experts in the following fields: aircraft CABX design and values, multi-physiological sensors for AI enabled autonomous transportation, high-touch services in tourism, and service marketing for airline companies. Finally, the findings section defines a set of challenges in the implementation of AIAS for CABX from the point of view of the customer, specifically the repercussions of implementing such costly systems - which are not justified in the current no-frills airline marketing models. The no-frills model strives to increase passenger capacity and traffic, decreasing employees, and remove unnecessary extras on board the plane as a way to increase profits.

Nevertheless, from the point of view of the service provider, AIAS has the potential to manage such influx of passengers without compromising service quality by, for example, attending to service pain points (problematic service interactions) that may lead to disruptive passenger behaviour by providing tools for emotional management to the user. Without exploiting this potential, the no-frills marketing model would likely find itself facing a breaking point at which the influx of unmanaged service failures critically affects the customer's perceived service quality during the most important stage of service, i.e., CABX services. Hence, by attending to the foundations of service quality (Grönroos, 1984), AIAS may add value and optimise quality maintenance in current airline marketing models. In this sense, the results indicate an overwhelmingly positive feeling toward the use of AIAS. AIAS is a system of particular significance when the user feels a sense of control over their service process, which can eventually lead to trust.

Background

Service Quality & Wellbeing

Emotions are subjective and timing matters; dealing with emotions during service consumption is therefore an important part of service management (Grönroos, 1990) as it can co-create significant values during times of need. Frontend service interactions that incorporate emotional elements into this relationship can lead to better customer perceptions of service quality (Almquist, 2016; Stickdorn, 2018, p. 48) and have a larger chance of alleviating service failures (Xu, 2019). Air travel services that have experienced vast leaps into digital transformation, like autonomous services (ACI, 2021), must somehow maintain this type of relationship, particularly in terms of trust in times of need. The significant value of trust is traditionally built through customer and FLE relationships, e.g., five-star hotels with budgets that facilitate higher qualities of human-agent interactions. In mass-transportation, however, the trend seems to be moving toward digitising the customer's frontend experience for the sake of functional values like saving time, expanding capacity, and efficiency (ACI, 2021). In this sense, view on AI in transportation have traditionally been geared toward such functional values, which target economic growth, rather than the emotional values once generated by traditional service means. Automatic services face challenges in dealing with service failures in critical moments.

AI-enabled services in the airline sector have successfully delivered functional values to both the customer and provider when it is placed as a backend service and works seamlessly (Biometrics, 2019; Tierney, 2021). On the other hand, traditional relationships that can lead to emotional values and trust may be undermined when human agents are replaced with AI frontend interactions. For example, emotional intelligence is a key factor in trust in FLE/customer relationships (Keller, 2017). Therefore, when it comes to users' direct interaction with AI channels, e.g., a chatbot that acts as a direct frontline employee, the value in human to AI interaction is positive only when human needs are understood and addressed accordingly (Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2018; Zamora, 2017). Unfortunately, in the precepctive of customers, “trust” has traditionally been ranked low in AI chatbot interactions (Nadarzynski, 2019); despite the fact that trust is the first element that can engage the customer emotionally, direct AI assistants/agents do not yet generate emotional values of that sort (Piñar-Chelso, 2011). Thus, in order for customers to place trust in AI services, it is necessary to reimagine the role of AI such that it is capable of co-creating values that can promote well-being and emotional intelligence.

Well-being is reached when a “balance” between a set of challenges and resource accessibility has been created. These challenges may be emotional in nature, but can be easily met when psychological and physical resources are available to the user (Dodge, 2012). On the other hand, when a set of challenges exceeds what the personal and external resources can offer, the balance is disrupted, causing the user to maintain negative feelings. Thus, complete service failures or customer frustration can be seen as the other end of well-being.

Service Design: A Service Process for Emotional Intelligence

The process of solving challenges is a form of well-being in itself. When solutions are within reasonable reach, this process creates a learning experience from which users start to learn about their own emotions, facilitating emotional intelligence and promoting the development of psychological resources (Dodge, 2012). Hence, when services can provide a “good life” through the use of technology and information channels,” digital well-being” is achieved (Burr, 2020). This means that AI enabled services must be reliable enough to facilitate the right kind of resources in times of need (Google, 2016), like instantaneous solutions when flights are delayed or cancelled; these could include offers of nearby accommodation or alternative flights and utilising historical data to personalise the time gap left by such service failure. Providing such dynamic access can be an essential component of AIAS, and is one of the many possible ways to create emotional values.

In terms of service design, personalisation is created through “design thinking”, a mentality that is essential for the ethnographic nature of service design research. Design thinking is when “human-centricity” is a key priority throughout the entire service creation process, i.e., service design tools (Miettinen, 2009; Stickdorn, 2012, 2018). This human-centric approach breaks down the complexity of the user's personality, which is necessary for building an effective relationship that co-creates values along the service journey. Such an approach can also define the user's archetype, which is essential for the process of creating a well-being strategy tailored to the user's individual experience. In this context, service design can produce AI-enabled interactions that exemplify human-centred values, generating value-in-use throughout the service journey (Jylkäs, 2020).

Another potential layer of service quality is the design of conversational interfaces that may lead both the user and the AI algorithm to determine the user's emotional state in real time [Interview 1]. Conversational interfaces are a natural way of communication through speech with the software, provided ubiquitously throughout the service (Janarthanam, 2017). This type of service may also reduce stress and empower the user with a sense of control. Users are the ones making the final decisions; in this sense, AI is augmenting the user's ability to identify their current emotional state and determine whether action needs to be taken. The awareness of having some psychological resources (e.g., identifying, controlling, or altering certain emotional states) can promote emotional intelligence and well-being.

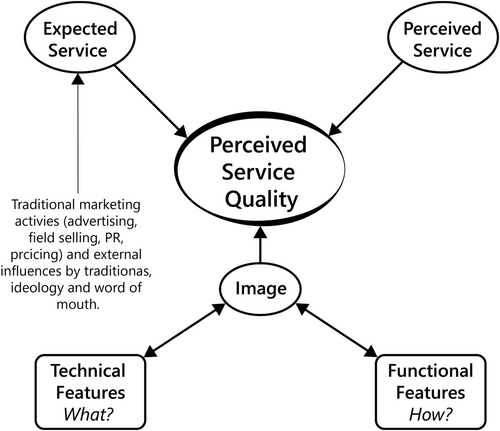

As previously noted, a customer's perception during the “functional features” of the services (service consumption/times of need) is the moment of during which their most significant perception of the service's quality is created (Görnroos, 1984). Similarly, airline services that focus on prompt service recovery (effective solutions during the moment of service failure) promote more positive emotions and “trust” as compared to “compensations” to mitigate past service failures (Wen, 2013; Xu, 2019). Therefore, to be able to project emotional awareness to the customer, which co-creates “values-in-use” (Grönroos, 2008), emotional intelligence must first be developed within the internal interactions of the organisation/company itself. For example, supervisors who can recognise their own emotions at work are more skilful in managing the emotions of their subordinates (Keller, 2017). In other words, the effect of a truthful and honest approach to emotional management within the organisational culture will most certainly trickle down to the cabin crew/customer relationship (e.g., Hofstede, 1980). The emotional intelligence of the cabin crew during CABX service interactions plays a critical role in perceived service quality, especially as compared to the employee's experience and overall performance. Specifically, customers' perceptions of service quality significantly increases when cabin crew can identify emotions through voices (Piñar-Chelso, p. 27, 2011). Hence, AI service interactions need to meet similar goals in order to maintain perceived service quality (see model below: figure 1).

Customers' perception of quality is majorly affected by the “functional features” of the service, i.e., how a service is performed and how problems are resolved in moments of need (see figure 1). This consumption period is critical because most of the bond between the provider and customer, including establishing rapport, co-creating values, and building a “trusting” relationship, happens here (Davey & Grönroos, 2019; Grönroos, 1984). Note that “technical features” here refers to skills and knowhow; thus, the technical features of a service may be regarded as the “high-tech” capabilities of the company and/or what channel is used to deliver the service or interaction.

In this study we focus on how CABX interactions can be enhanced via the integration of AIAS and how that may affect the perceived service quality: AIAS for Cabin Experience Service Quality (CABX-Q). Moreover, we explore the different channels through which emotional engagement, values, and intelligence can be designed within a service process. In other words, we examine how “high-tech” technological capabilities (e.g., online connectivity and state of the art devices) are turned into “high-touch” opportunities (i.e., emotional engagement, intelligence, and personalisation).

High-Tech: Multimodal Sensor Technology

Multiple streams of data are essential for achieving comprehensive results. To that end, a multimodal sensor utilises several high-tech devices to provide access. For example, multiple sensors like facial recognition, sound ambiance, voice tone detection, and physiological and emotional detectors can create a fusion of data that leads to enhanced multimodal analysis of the in-cabin experience (Bland, 2017). In this case, the machine is learning from multiple areas, which gives the AI enough resources to cross-correlate the “surrounding world in real time and respond to our behaviour and feelings appropriately,” which, in turn, develops the user's emotional intelligence (Bland, 2018). For instance, the general mood of the cabin environment can be measured using noise, motion, and chemical imbalance sensors from which the general ambiance can be analysed; additionally, heart rate and physiological sensors embedded within the seat can analyse customers' personal experiences [Interview 1]. When data from such multimodal resources is analysed, AIAS can more appropriately predict solutions in times of need and augment employees' capabilities.

High-Touch: AI Augmented Services. Humanised Technology

High-touch refers to digital services that utilise human factors. For example, when high-tech is able to provide sensations, placing the user in an immersive environment where vision, sound, tactile touch, and emotions are felt, the experience is transformed from high-tech to high-touch (Huang, 2021; Interview 3). This is one of the most significant roles AI can play in improving CABX digital services. Here, the functional features of service quality (service consumption) are enhanced by augmenting these human senses and improving the decision-making process for the customer. In summary, high-touch is the process of personalising the user's digital experience (see figure 2 below).

However, AI interactions as they are now may not create trust. Frontend interfaces and machines attempting to characterise AI to resemble human actions fail to build a trusting image of the capabilities of AI in terms of services. This attempted human-like resemblance reminds users that current AI interactions are vastly different from human interactions. Therefore, humanising AI to mimic human behaviour may lead to more harm in terms of trust instead of creating emotional value (Jylkäs, 2020; Tian et al., 2017). Conversely, helping the user better understand the values of AI backend capabilities can lead them toward giving more attention to the machine learning process, thereby creating values (Stickdorn, 2018, p. 48; Jylkäs, 2020). When the user is aware of the value HMI can give, namely, “providing relevant resources at the time of need,” this may build trust toward data sharing, enhancing the quality of the data being provided. Hence, the process of machine learning needs to be highlighted, not a humanoid depiction of AI (Jylkäs, Äijälä, Vuorikari & Rajab 2018; Jylkäs, 2020). Trust may then develop when such interaction dynamics are acknowledged. In other words, the machine learning and human interaction process can be essential for building trust and improving the data input quality. As a result, high-touch interactions can now be enhanced and projected through the data output of AIAS.

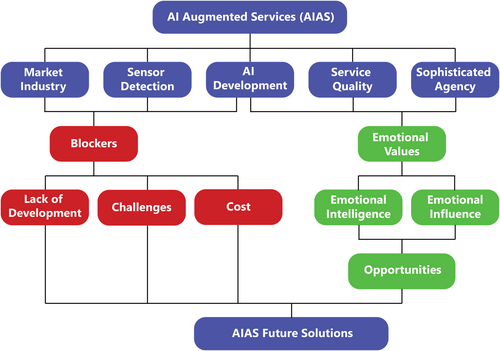

Detecting emotions during service consumption is vital for offering solutions. At this time, most user behaviour is being witnessed by both the machine and the users themselves. This can be coupled with users' historical data (past experiences with the service) and their emotional state before boarding the plane. Customers that have been flagged as experiencing stress or service failures prior to boarding could then be given tailored attention. In this case, it is up to the cabin crew's “service design process” to activate action strategies that may alleviate pain points (Miettinen, 2009). Service design has the potential to proactively discover and respond to passenger needs, optimising the service journey not only during the inflight CABX but the overall home-to-home journey. This is because service design gives research tools that maintain the user as a focal point for technology-driven and delivery-oriented services. One case example would be creating dialogue with the user through the use of a high-tech AI natural language. The conversation would attempt to validate the emotional state of the user in a simple manner, highlighting critical emotions that may need to be addressed, which would then allow for the use of high-touch as the AIAS system suggests tailored solutions to the user. These solutions could be performed by the user, the flight attendant, or AI when permission is given, thereby augmenting the user's ability to recognise critical issues and take appropriate action (see figure 3 below).

In this sense, it is important to analyse the user's state of mind from multiple angles to achieve more accurate results that are more accurate. For example, some customers might have higher heart rates because they are playing a game or watching a thriller on board. Thus, it is important that the AI multimodal process evaluates the situation appropriately, analysing the alarming physiological data together with multiple other sensors as well as historical data. In this way, a more accurate result that assesses more logical possibilities as to why these customers are showing certain vitals can be achieved (Bland, 2017, 2018). Conversely, a customer might be showing signs of discomfort from feeling claustrophobic. In this case, AIAS can suggest simple tricks to alleviate such feelings; the user could be given options to change the mood of the CABX by manipulating the lighting and illuminated angles of the seating area to make their personal surroundings seem more spacious and relaxing (Interview, 2; Stamps, 2009). This also offers the customer a sense of instant “control” over the CABX environment [Interview 2].

Methodology

This research was designed in four phases: benchmarking online resources, literature review, expert interviews, and analysis. The benchmarking tool of service design was majorly utilised in this study and is the initial method approach from which interviews were later conducted. Benchmarking is a form of “industrial ethnography” (Miettinen, 2019, p. 20) through which various sectors of transportation are benchmarked according to marketing approach, AI development, and users' well-being standards. Essentially, this is why the process of benchmarking takes place, “benchmarking facilitates concretising new ideas about practices and evaluating which ideas have proven to be good or bad,” (Miettinen, 2019, p. 488). Online databases were examined in order to define the state of the art of AI development in the general transportation field. This technique was necessary in order to find key technologies being used elsewhere, not just in the realm of air travel (e.g., ACI, 2021). Here, information gathered from other transport-related sectors, such as the automotive and tourism industry, is taken into consideration, “evaluating [them] and learning from best practices,” (Miettinen, 2019, p. 488) to reimagine airline CABX services in terms of AIAS.

The above process offered several contacts from which four expert participants were selected (see table below). Each interview involved one hour of face-to-face, semi-structured, and open-ended dialogue; all interviews took place online (Khan, 2014). Participants were sent emails that included an invitation to the interview, a brief explanation of the research topic, a data release agreement, and some general ethical matters. Initially, structured interview questions were geared toward the participants' specific fields, which were generally related to technology and transport while open-ended questions were designed to address the different ways through which technology can produce emotional values. This technique allowed the participants to use their expertise and knowhow to come up with their own conclusions on the concept of AIAS for CABX (Khan, 2014; McCormack, 2004).

Profile of interviewees.

| Interview | Field and Expertise |

|---|---|

| 1 | Sensor technology: AI autonomous driving - Chair of the working group developing global industry standards for the ethical design and use of systems that measure, simulate, or respond to human emotional and cognitive states. |

| 2 | Director of Cabin Experience, Associate Technical Fellow - Currently leading a large team in an effort to document the Boeing design process for the passenger experience. In support of the “Boeing Confident Return to Travel” initiative, informs BCA engineering teams of the most salient aspects of the cabin experience in a post-Covid-19 world. Director of Cabin Research and Passenger Experience, Airplane Product Development - Envisioning and executing key cabin and passenger experience research questions, managing a yearly $1 M budget, and commissioning RFPs and project management alongside international consultants. |

| 3 | High-touch service in tourism markets - Lecturer in several tourism-related fields of study, including electronic commerce, customer service, customer relationship management, and daily operational management. Working on research and development in multidimensional tourism. |

| 4 | Airline Market and CX Services - Working in corporate strategy, automotive smart mobility, and Digitalization and commercial vehicles. Company size >10,000. Previous position - Innovation Manager, involved service prototyping, aerospace, aircraft OEM, company size >10,000. |

The audio from the interviews was manually transcribed and coded according to the in-depth dialog (Deterding, 2021). Transcription took note of tonality in the participant's voice to better understand how they feel about certain topics. This process produced roughly thirty-five pages of text from which four major code groups were established: AIAS, Emotional Values, Blockers, and Opportunities “future solutions” (see figure 4 below). Further analysis produced twelve subgroup themes from which a pattern emerged (Deterding, 2021; McCormack, 2004), as shown in the illustration below.

Findings

AI Augmented Services (AIAS)

The transportation industry has a phenomenal opportunity to harness and engage the user with emotional values during the CABX service journey [1]. In order to do so, users must feel that they have some sort of control over such services [2]. The AIAS process may start with high-tech sensors that are able to collect data from multiple sources. Machine analysis must come from a multimodal approach wherein multiple sensors, e.g. voice tone detection, facial recognition, and physiological sensors, enable a flow of data that can be synthesised to determine how the user came to a certain feeling in order to create a clear, accurate reading of their emotional state [1]. Here, a dialog between the user and the machine validates the emotions that a user might be feeling. In this sense, historical data, data that has been previously collected from the user to personalise their cabin experience [4], can be integrated into the dialogue to assist in better decision-making, thereby creating personalisation. Additionally, the user can be given sophisticated agency whereby the amount of AI interactions they have is under their control [1].

Even so, a sense of control may create more positive emotional values than personalisation. Being up in the air all alone can be an overwhelming experience to some passengers [2]. This state of mind places customers in a unique position in which they sometimes may question matters of extreme importance. In this sense, control may lead to a balance of emotions when such state of mind is triggered, where long-term life changing decisions may lead to well-being. Hence, any kind of control given to the passenger is appreciated, even if it is a façade [2].

As for the service provider, there are many responsibilities that cabin crew must take care of that go beyond bringing a blanket to a passenger, including safety measures and security protocol. AIAS could improve the decision-making process of FLEs and cabin crew, maximise priorities, and “increase staff efficiency” [1]. Nevertheless, if AIAS is playing the role of the mediator “broker”, then the CABX journey needs to be mapped out from both the passenger's and the cabin crew's perspective [2]. Such journey maps would visualise the touchpoint interceptions through which AIAS can play its role in enhancing service quality, building a structure for this concept to be implemented.

Emotional Values

Three major patterns have emerged in connection to AI and emotions, namely user control, perception of time, and emotional intelligence. Firstly, the CABX can be a delicate and unique situation for each passenger and they often have very limited control. Thus, “any type of control that you can give a passenger on a plane is awesome,” [2] even if this control is simply their own perception. For example, the waiting period, whether queuing at the gate to board the plane or waiting during the journey itself, is often perceived differently from one passenger to another. AI can attempt to make this passage of time seem shorter and more, “enjoyable” [2].

However, there are many influences that might hinder the relationship between AI and the user, rendering AI agents “annoying”. Conversely, if users are aware of the benefits AI can offer during their journey, they might become inclined to increase that interaction, thereby providing more accurate and higher quality data. When the data consent dialogue is designed in a way that allows the user to acknowledge the benefits of data sharing, such as emotional health, awareness, and intelligence leads to better life changing decisions, and when the user is placed in full control to the desired level of AI engagement, the AI assistant, or so-called “emotional intelligence buddy”, can become a vital tool rather than an annoying pop-up [1]. Thus, higher quality AI interactions produces more accurate historical data that can be integrated into high-touch CABX services [3], allowing the passenger's perception of time during future journeys to become more personalised and “enjoyable” [2].

Challenges

AI-based emotional values in transportation services have not yet reached their full potential [1]. The cabin environment of a commercial plane is a particularly large challenge in terms of personalisation: Where should CABX sensors like cameras be installed in this public environment? How can company and passenger approval be obtained? Do passengers want to emotionally invest in this technology? [1]. The most notable and primary challenge in terms of AI development, however, is cost. Generally, the popular market model of no frills, with limited passenger space and limited baggage weight, seems to be successful for most airline companies nowadays [4]. Aspects of personalisation, such as meals and overall ambiance, can be achieved using simple passenger historical data that does not require expensive AI machinery [4]. Thus, the cost of developing AI for CABX and carrying its extra weight (equipment and devices that make onboard AIAS effective) is rather unjustified in the no frills market model.

DIscussion: AIAS Future Solutions

Co-creating values during service consumption, i.e., “value-in-use” (Grönroos, 2008), when the customer and the service provider are interacting is the most significant dimension of service quality (Grönroos, 1984). Increasing the passenger's perception of control during a flight allows values to be co-created during one of the most critical phases of an airline service. This, in turn, can alleviate tension and assist in the maintaining of trust in AI-enabled services. When trust is established and the user acknowledges the benefits of sharing data with AIAS, they feed more accurate data into the system [1], co-creating values-in-use during service consumption (Grönroos, 2008). AIAS may therefore help CABX users (customers and employees) in three major areas, namely augmentation of human capabilities in services, users' sense control, and emotional management and intelligence. When such elements are calculated and offered throughout the AIAS, it may very much become a winning factor in terms of perceived service quality (Grönroos, 2007). With AIAS, the user is viewed in a human-centric way rather than a simple service in exchange (e.g., Miettinen, 2009; 2014). Thus, business models that aim to increase passenger numbers by reducing space and service interactions may be profitable but are likely having adverse effects on the customers' perception of service quality. The trajectory (future resilience and expandability) of such models is therefore questionable without a reliable quality management strategy.

Indeed, CABX is a unique environment with extremely limited options for the customer. Nevertheless, AI can be a significant tool that can alter, if not improve, the perception of time in this environment [2]. Additionally, AIAS has the potential to provide personalised services, which is the most crucial step toward high-touch on-board services. In this sense, high-touch CABX services aim to increase user productivity, meaning that time in the air can be thought of by the customer as time well-spent. This creates room for improvement in the current airline market model in terms of increasing emotional values during service consumption. Nevertheless, AIAS for high-touch services require high-tech capabilities [1; 3] like reliable sensors and devices. Whether high-tech is offered within the CABX in the form of devices like fixed infotainment seat consoles or customers' devices like mobile phones and laptops, technicalities like online connectivity and device performance need to be reliable for high-touch services to take place.

More passengers in increasingly limited spaces means that safety-related responsibilities are intensified for the cabin crew and FLEs; flight attendants become responsible for much more than food service. To this end, AIAS can have a significant effect on service performance, allowing FLEs to perform their safety and security duties whilst maintaining the same level of frontend service quality during face-to-face customer interactions [1].

For trust to be built and for the above scenarios to occur without compromising the customer's perception of service quality, the customer needs to be in full control throughout the process. This means that the level of AI control, e.g., introverted versus extroverted AI interactions for augmented services (Audi Concept, 2017), should be up to the customer, allowing the user to completely opt out of the machine learning and suggestion process; this is also known as sophisticated agency [1]. This will allow a wider range of customer archetypes to interact with AI backend services based on the level of AI assistance they want. Additionally, in a multimodal approach wherein AI voice detection is intended to identify the passenger's emotional state and offer solutions accordingly, AIAS interactions may significantly enhance the customer's perceived service quality (e.g., Piñar-Chelso, 2011). However, ethical matters must also be addressed; users need to know how their data is being used and stored (e.g., General Data Protection Regulation of the EU: GDPR) because software transparency increases the ethical operation of the service.

To achieve accurate emotional interpretation, the machine learning process must acquire necessary data through interactions that are justified to the user, the provider, and other responsible authorities. The way to increase beneficial AI services is to educate the user on the purpose of such interactions, namely the need to maintain a healthy emotional state for well-being and productivity purposes. Through a more natural HMI dialog process (Jylkäs, 2020), the user must acknowledge that such interactions can enhance bilateral emotional intelligence, both the user's emotional self-awareness and the AI's quality of emotional detection, and that emotional intelligence leads to benefits in successive services. The process of HMI for learning purposes is therefore justified when the benefits of high-touch services are amplified [1; 3].

The benefits of AIAS can also be expanded into other stages of the service. For example, in future pre-service stages (Stickdorn, 2018), customers that have accumulated historical data may find it easier to plan and book their upcoming trips, enabling the customer to envision their next cabin experience (Interview, 2; Google, 2016), incorporating more high-touch elements [3]. This would allow airline companies to obtain a better read on customers' “expected service quality,” (Grönroos, 1984) and enhance their services accordingly. Naturally, AI is more capable of calculating and evaluating a large amount of transactional data than any human agent (Jylkäs, Äijälä, Vuorikari, Rajab, 2018), allowing for better management and multimodal analysis of the stupendous amount of data collected throughout the journey [1]. This may also help the system identify and group individuals into archetypes based on their service expectations. In other words, customers could be identified according to their psychographic profile, their goals, desires, dreams, and emotional needs (Zins, 1998). Airlines with such access are then empowered to target certain archetypes that may need more specialised attention while maintaining the level of service quality across multiple types of customers. As for the post-service stage, customers' emotional involvement (Stickdorn, 2018) may be increased by connecting AIAS historical data with the online service evaluation stage (e.g., Siering, 2018). This allows airlines to improve their marketing communications (e.g., Finne, 2017) by evaluating users' emotional satisfaction and identifying service failures (Vázquez-Casielles, 2007; Xu, 2019; Wen, 2013).

Limitations

Due to cost and lack of development, current AI autonomous services do not come close to reaching any of the necessary emotional engagement and values discussed in this study [1; 4]. Additionally, in terms of “co-creating” emotional values during service consumption (value-in-use), which is monumental in customers' perception of quality, mass transposition onboard interactions are still heavily reliant on the dynamic relationship between customers and employees (Radic, 2018). Thus, more research on the development of AI for emotional values and service quality is needed.

Conclusion

AIAS is a concept solution that combines the power of technology and the judgement of humans to achieve emotional values that lead to an increase in service quality. In this sense, AI capabilities for emotional values are not too far-fetched if the AI is designed through augmented services that always involve the users and place them in full control. The idea here is to give some sort of access to the customer, and the outcome can create emotional values that maintain service quality without requiring direct human-agent interactions. Thus, AIAS uses technology to create a link between all parties involved within the cabin experience, including the customer, the cabin crew, and the AI agent. This concept offers a realistic approach to CABX AI services where the dynamics of human interactions are maintained as the power of current advanced technology is utilised. The benefits of installing such systems within the CABX can help customers use their time more productively, personalising their experience and leaving a more profound impression of service quality. AIAS can also assist cabin crew in accomplishing tasks more quickly, leaving more time for critical matters. Solutions such as these can come with great financial risks in terms of development and implementation. However, the business model most widely used in today's airline companies also calls for better management of the maximised number of passengers on board the aircraft. The development of AIAS can alleviate the feeling of being constrained while in flight; this can be initiated by guiding the passenger toward better management of their emotions and time.

Biographies

Vássil Rjsé, is a PhD candidate in service design at University of Lapland, Finland. Vássil focuses on systemic design that utilises artificial intelligence in airline digital services.

Dr. Titta Jylkäs, is a senior lecturer in service design at University of Lapland, Finland. She is focusing on strategic service design in the digital transformation of customer services utilising artificial intelligence.

Satu Miettinen, is a Professor of Service Design (2016-) at the Faculty of Art and Design, University of Lapland in Finland. She is leading service design research group “Co-Stars“. She has also worked as a Professor of Applied Art and Design during the years (2011-2016). Satu Miettinen is an active artist and designer in the area of socially engaged art and ecofeminist photography. She also works at BioARTech Laboratory.