Start-up Accelerators as Service Design and Business Model

Abstract

Startup accelerators offer a range of services to entrepreneurs that enable them to accelerate growth and development in just a few months. Typically, small-, and medium-sized, growth-oriented companies are supported early in their development through offers of education and training, mentoring, consulting, and venture capital. The startup accelerator “Growth Train” of Business Lolland-Falster – a regional development organization in Denmark, has been the subject of a closer investigation as a service journey and business model. Four distinct factors make accelerators unique: time-limited, cohort-based (a standard course for a selected group), mentor-driven, and typically ends with a ‘demo day’. The analysis of Growth Train is based on Service Design Thinking and theories on Business Models. It contributes to the theoretical understanding of startup accelerators as a service journey for the participating startups where Service-Design Thinking plays a crucial role in the design of the accelerator. It also explains how the accelerators create value for the selected group of startups. Startup accelerators also represent a Business Model (value proposition) for the managers of the accelerators and the stakeholders in the local business ecosystem. It also offers economic growth and employment for outlying areas like Lolland-Falster in Denmark.

Introduction

Start-up accelerators offer a range of services to entrepreneurs and startups that enable them to accelerate growth and development in just a few months. Typically, small, and medium-sized, growth-oriented companies are supported early in their development through offers of education and training, mentoring, sparring, and venture capital.

There is no unambiguous definition of startup accelerators. Still, Cohen, Fehder, Murray, and Hochberg (2019) have identified four distinct factors that make accelerators unique: time-limited, cohort-based (a standard course for a selected group of startups), mentor-driven, and typically ends with a ‘demo day’.

Although many startup accelerators are built on a service design that contains the same elements and themes in the design of the specific service offering, they are also different. This is the case when we look at accelerators as business models because when it comes to their earnings, they can come from investments in individual startups, public subsidies, or financing by larger companies.

In Denmark, various offers for participation in startup accelerators exist, some as departments of international accelerators such as Rockstart in Copenhagen, and others more locally organized such as Growth Train (‘Fast Track’) under the auspices of Business Lolland- Falster (a local business development organization in the southern part of the region of Zealand). With a focus on international startups in the agricultural and food sectors, the latter has been the subject of detailed analysis concerning the service design and the basic business model.

In “Growth Train”, the target group is either newly started companies (including spinoffs from Roskilde University) or established micro-companies with 1–5 employees and a lifespan of 1–8 years. They often have significant economic growth and employment potential, as they have proven that they can sell their products and services. Often, they lack the support of a local ‘entrepreneurial’ ecosystem to reach the next stage of their growth curve (Goal and Framework Plan 2020, Business Lolland Falster 2020).

According to Cohen (2006), an ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’ constitutes “a diverse set of independent actors within a geographic region that influences the formation and eventual trajectory of the entire group of actors and potentially the regional economy. Entrepreneurial ecosystems evolve through a set of interdependent components which interact to generate new venture creation over time” (Cohen, 2006). Cukier et al. (2016) have, in contrast, defined a startup ecosystem as “a limited region within 30 miles (or one-hour travel) range, formed by people, their startups, and various types of supporting organizations, interacting as a complex system to create new startup companies and evolve the existing ones” (Cukier et al., 2016). Start-up accelerators are thus part of many different contexts and roles in the respective local ecosystems (Cohen et al., 2019).

The following analytical angle on startup accelerators is Service Design Thinking (Stickdorn et al., 2018). The analysis of accelerators as Business Models (Pauwells et al., 2016), built on a design perspective on business models formulated by Zott and Amitt (2010), and seeks to identify the primary design elements and themes in the design of accelerators as business models (value propositions).

Research questions

- What are the characteristics of newer startup accelerators compared to previously completed incubation courses for entrepreneurs?

- How can an accelerator program such as Growth Train under the auspices of Business Lolland-Falster be seen as a service design (a ‘service journey’) and as a business model (a value proposition) based on Service Design Thinking and The Business Model Canvas, respectively?

- What proposals for new development in the existing accelerator program does the analysis of Growth Train as a service design and business model raise?

The structure and theory of the paper

The research questions answers are structured in the following parts, representing the task's structure and analysis strategy (Jensen and Kvist, 2020).

In the first part, a delimitation of the phenomenon of startup accelerators concerning previous generations of incubation processes is made. The second part presents the main theories and concepts of the task (Service Design and Business Model Generation). The third part discusses used data and methods based on an empirical study of “Growth Train” conducted by Business Lolland-Falster and Roskilde University in 2020. The fourth part presents the data analysis and discusses its results and proposals for further development of Growth Train as an accelerator. Furthermore, the fifth part summarizes an overall conclusion for the analysis in the paper.

Limitations

The present paper primarily represents an analysis and discussion of how a startup accelerator constitutes a service design and how it provides value for participating companies and stakeholders (the ecosystem) and thus functions as a business model.

It is a single-case study, which means that, empirically, it is not possible to generalize to other cases of startup accelerators and incubation processes (i.e., a literal replication). There is only a discussion of whether it is possible to make a theoretical replication (Yin, 2018) confirming a theoretical understanding (‘framing’) of accelerators as a ‘service design’ (service journey) and as a ‘business model’ (value proposition), respectively.

From incubation to acceleration

Business incubation has been a recognized and widespread tool for promoting entrepreneurship since the mid-1980s (Møller & Grünbaum, 2017). The first generation of incubation courses primarily offered access to office facilities for entrepreneurs, the second generation focused on offering non-physical services (Business consulting), and the third generation promoted technology-based Business. This change over time in the dominant ‘value proposition’ to entrepreneurs and an increased focus on earnings and specialization has been overlooked in large parts of the literature on incubation processes (Bruneel et al., 2012).

The accelerator model constitutes a further development of the incubation model away from a service design focusing on physical services (e.g., offers for renting office facilities) only to more knowledge-intensive business service and consulting (e.g., on innovation and patents) and mentoring. The focus is now on supporting an intensive interaction between startups, teachers, mentors, and other participants and more robust monitoring by the program management. In addition, education and training must also increase the opportunity for rapid and accelerated development and growth in the participating startups.

Although there are significant differences between incubation processes in the early stages and the current examples of startup accelerators, no new tools and models have emerged to describe and investigate the crucial differences in design elements and themes in the incubation and accelerator programs used. This also concerns their business models (Clarysse et al., 2015).

This need has not diminished as accelerators have gained popularity with many startups, investors, and organizations such as universities, larger companies, and regional development units attracted by launching accelerators for selected target groups. However, starting an accelerator requires a clear vision and strategy concerning the goals sought to be achieved by establishing the accelerator. The ability to work purposefully with a well-defined category of startups, formulate clear objectives for their development, accelerator profit- and return orientation, and the perspective on the relationship to stakeholders (Cohen et al., 2019; Hallen et al., 2020).

In the literature on startup accelerators, four main types can be identified based on the type of organization that supports and operates them. The first type refers to an investor-driven accelerator. As the name implies, this is funded by business angels or venture capital funds focusing on the return on investment in startups. They typically focus on startups in their later development phase. The second is a government-initiated accelerator that typically supports startups at a very early stage of their life cycle to stimulate entrepreneurial activities in the ecosystem locally or regionally to ensure economic growth and more employment. A third type is a corporate accelerator, typically established to “insource” external innovation (Tidd & Bessant, 2016) and promote internal innovation among the company and its customers. They are typically not profit- or return-oriented but aim to match the selected startups with potential “corporate stakeholders”. The fourth and final type is the university-controlled accelerators, which often do not offer “seed money” or require startup investments. Thus, they constitute non-profit educational units that support entrepreneurship among students and academic staff to create increased innovation within and outside the university environment.

In addition to the four types of accelerators, there may also be a difference based on what industry-specific and geographical focus they occupy. They will typically be concerned with influencing the local business ecosystem if they have a local focus. In contrast, a focus across several countries aims to create an offer based on cross-border networks of actors and partners. Finally, a more global perspective focuses on being present in many different international locations. The focus is on the relationships between different ecosystems as a framework for developing international startups (Nesta 2014).

However, increasing competition between accelerators has led to increased specialization in industries and geography based on the desire to offer startups increased value through access to more qualified accelerator environments and closer relationships with relevant customers, partners, and markets. However, the same industries still recur, e.g., technology, media and communication, financial services, health, food, etc.

Service design and business model

According to Zott and Amit (2010), a company's business model constitutes “a system of interdependent activities that transcends the focal firm and spans its boundaries. The activity system enables the firm to create value and appropriate a share of value in concert with its partners. Anchored on theoretical and empirical research, we suggest two sets of parameters that activity systems designers need to consider: design elements - content, structure, and governance - that describe the architecture of an activity system and design themes - novelty, lock-in, complementarities, and efficiency - that describe the sources of the activity systems value creation” (Zott and Amit 2010, p. 216).

A design perspective on accelerators as an activity system and a range of services seems relevant concerning exploring new types of accelerator models. This perspective can precisely contribute to tools and models to identify and assess similarities and differences in design elements and themes in the selected accelerator models. It can distinguish new models from existing ones by focusing on crucial new elements (new content, new structure, and new forms of governance), pointing out differences in rationales concerning whether they govern by a profit motive or a desire for local growth and employment. Noteworthy is their impact and relation to the local business ecosystem through locking relationships, complementarity, and efficiency.

Based on Service Design Thinking (or Doing), which, according to Stickhorn et al. (2018), stems from a “practical approach to the creation and improvement of the offerings made by organizations” with an origin indesign thinking and explicit agreement with ‘service-dominant logic’ (Vargo & Lusch 2004) in marketing, the principles behind service design thinking defines (Stickhorn et al. 2018, pp. 26–27): “a human-centered, collaborative, interdisciplinary, iterative approach” that is “sequential” with…” services visualized and orchestrated as a sequence of interrelated actions”….” that meet the (real) needs of Business, the user and other stakeholders” with… a “holistic” approach.

A frequently used tool in ‘service design thinking’ is different types of ‘Journey maps’, which describe the ‘service journey’ (and associated touchpoints) that customers typically carry out, e.g., a startup company in an accelerator process. Journey maps are a flexible tool used to 1) visualize and collect customer experiences, 2) understand how existing services work, uncover ‘painful’ and less good experiences at touchpoints in the service journey and opportunities for improvements in this, and 3) create an idea of future services (Stickhorn et al. 2018, pp. 44–45).

- Proposition (value proposition) - What does the program offer the participating startups and stakeholders,

- Process - how the program is running.

- People - who are involved, and

- Place - Where is the host for the accelerator?

As seen from this 4P model, an essential aspect of the design considerations is which value proposition the participating startups meet. Thus, Kohler also perceives accelerators as a business model in line with Zott and Amit (2010) and connects a service design perspective with a Business Model thinking, but deepens the common understanding of these frameworks by, in addition to a process perspective, involving who is involved. (‘People’) and the host (‘Place’).

According to Teece (2010), an essential point in this connection is that “Business Models articulates the logic and provides data and other evidence demonstrating how a business creates and delivers value to customers. It also outlines the architecture of revenues, costs, and profits associated with the business enterprise delivering that value”. Chesbrough (2010) has also examined what characterizes the typical business model and concluded that these fulfill several functions, cf. Figure 1:

Source: Chesbrough 2010.

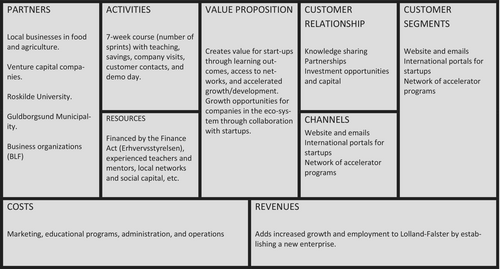

In experiments with an accelerator's business model, mapping the processes in the business model and describing the accelerator as a ‘service design’ (Stickdorn et al., 2018) provides access to conduct the experiments. The service design provides new combinations of different process elements and learning methods in the accelerator process (design elements and themes, cf. Zott and Amit 2010). It has also been the case for Growth Train since its inception in 2017. Osterwalder and Pigneur published 2010 a practical method for mapping business models that has become widespread. They suggest that when generating new business models, you must break them down into nine ‘building blocks’, Figure 2.

Source: http.//business-model-design.blogspot/2005/11/what-is-business-model.html

In a better-known and used version, the nine elements incorporated in a Business Model Canvas (a “painting”) describe a business model's elements, e.g., the one that applies to Growth Train.

A Business Model Canvas functioning as a “generic” model can be used generally and as a method not dependent on a specific type of accelerator and its context. It does not have to be a “profit-driven” model where investors achieve a return on investment in startups. A ‘revenue flow’ from an accelerator controlled by an authority/business promotion organization can instead be the economic growth and additional employment that startups eventually bring to the local community.

Data and methods

Together with Business Lolland-Falster, Roskilde University conducted 2020 follow-up research for a demonstration project on “Accelerator in outlying areas” (Foundation for Business Lolland-Falster 2020; Møller, 2020). The aim was to document the Experience with the accelerator used (its design and learning model) and communicate the main conclusions to relevant stakeholders (participants, trainers, mentors, companies, investors, authorities, and the management of the accelerator course) to identify ideas for further development of the accelerator in the following year.

In a time-limited and accelerated organization, the follow-up research can be considered a field study (Jones, 2014). The main elements are a seven-week development course for a selected group of international startups, all with a background in very different entrepreneurial cultures outside Lolland-Falster and Denmark.

Field studies in organizations typically consist of complex empirical studies that explore attitudes, behaviors, needs, experiences, values, practices, etc. Data produced in these studies are predominantly qualitative, i.e., verbal descriptions, but can also be quantitative, i.e., distributions of registered responses in completed questionnaire surveys (Burgess, 1984).

The study of Growth Train included using an online questionnaire (Møller, 2019) sent out to the participants in accelerator programs in 2017, 2018, and 2019 (collecting quantitative data). It also conducted qualitative interviews with startups, teachers, mentors, investors, and companies in the ecosystem during the accelerator process in 2020 (collected qualitative data). Observations of activities/situations during the Fast Track process, together with studies of documents containing texts, sound, and images, e.g., a used Playbook (Sørensen, 2020), course plans, slides, video presentations with the participants' business models used on Demo Day, etc., i.e., used a ‘mixed method’ (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009).

All in all, extensive material that documents the accelerator Growth Train (“Fast Track”) in various ways as an accelerator design (‘service design’), learning environment, and learning outcomes for the participants and as a service experience, as well as a business model that maps the accelerator's relationships and impact on the local business ecosystem on Lolland-Falster were done (Møller et al., 2021, pp. 15–24).

Analysis of growth train (‘fast track’)

Concerning the research questions, the following focus is on 1) characterizing Growth Train (‘Fast Track’) as accelerator design, 2) giving an overview of ‘Fast Track’ (7 weeks sprint) as a ‘service journey’ through the use of Experience-centered Journey Map (Stickdorn et al., 2018), 3) an analysis of the accelerator as a business model (value proposition) using Business Model Canvas and 4) proposals for new development given the experiences with Growth Train (‘Fast Track’) as a service design and business model.

Fast Track as accelerator design (type)

The Growth Train (‘Fast Track’) 2020 does stand out compared to other accelerator designs (e.g., the accelerator Rockstart, which is investor driven, Neslé R&D Accelerator, that is company-driven, and EIT, which is a network supported by the EU). Its purpose is to give a qualitative boost to the participating startups' business models and an increased focus and access to customers and partners in specific markets in Denmark and locally on Lolland-Falster. In addition, it will increase the number of business startups in the region and demonstrate how entrepreneurship can contribute to increased growth and employment in peripheral areas (Fonden Business Lolland-Falster 2020). In addition to this geographical focus, the Growth Train (‘Fast Track’) also involves a specialized focus on the agricultural and food area as a position of strength on Lolland-Falster.

By being fully financed by funds from the Finance Act (Erhvervsstyrelsen) without an offer of “Seed Money” nor a requirement for equity shares, the accelerator differs markedly from more commercial accelerators that are typically investor-driven. Growth Train is also led and organized by Business Lolland-Falster. It thus represents a classic example of an authority-driven accelerator focusing on creating growth and employment in the local community (concerning the local business ecosystem) and net earnings for the investor or benefits for a larger company (company-driven accelerator).

As a learning structure and environment, ‘Fast Track’ has a relatively fixed program of courses with relatively detailed curricula (Møller et al., 2021), which is often the case for authority-controlled accelerators. Despite the regular program flow, the implementation has been flexible and adapted to the individual participants through practiced mentoring, networking, meeting with potential partners, and a closing demo day as essential elements in the activity (Zott & Amit, 2010).

There are also more criteria in selecting startups than in other accelerators, focusing on international startups (predominantly EU-based) with some experience and longevity, focus on food and agriculture, and requirements for ‘local relevance’ regarding Lolland-Falster. In addition, as something very central to the accelerator, a follow-up and interaction with former participants in Growth Train is included through frequent contact with them (Alumni program).

It is also characteristic of Growth Train as an activity perceived locally as one of several ways to achieve local economic development independent of external funding. Specifically, the ambition has also been for the accelerator to be perceived as attractive and a fair offer to startup companies, which provides a value offer that promotes the companies' growth and development. Its branding locally and internationally ensures a reputation as an attractive accelerator offer. It also attracts qualified startups from abroad as applicants.

Fast Track as a ‘service journey’

Journey maps help us find gaps or deficiencies in the customer experience and investigate possible solutions (Stickdorn et al., 2018). It also applies to the Experience of, for example, the learning outcome in an accelerator course. A ‘journey map’ can be compared to a screenplay or the ‘Play Book’, used explicitly on the Growth Train (‘Fast Track’) in the autumn of 2020 (Sørensen, 2020). It is structured as a ‘sequence of steps referred to as events, moments, experiences, interactions, activities, etc.” (Stickdorn et al. 2018) or concrete ‘sprints' in a Playbook for a Fast Track course. Journey maps can be based on several considerations: whether they are built on assumptions/or factual conditions, current/or future situations, a customer/or employee perspective, product, or experience-centered actions (e.g., frontstage and backstage), etc.

There is also the possibility of using Service Blueprints, an extension of journey maps in this connection. They connect customers' experiences, actions, touchpoints' frontstage’ and employee activities, and support processes' backstage’ in the service journey. A ‘Service Blueprint’ for Fast Track 2020 is divided into five parts with a ‘front stage’ divided into, e.g., ‘startup activities' and ‘touchpoints as well as activities' backstage’ are listed in Table 1 as an example of a mapping of activities (services) on the service journey for the benefit of the participating startups. It is based on data from an investigation into the Growth Train Accelerator (Møller et al. 2021):

| Application and Selection | Onboarding, presentation, and prioritization | 7-course weeks with several sprints | Demo day | Follow up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front stage |

Startup Activities |

Startups apply accelerator | A start-up enters into an agreement of participation, presents a business idea, and prioritizes themes. | Seven-course weeks (sprint) with development of the business model (idea) documented in a ‘pitch book’ with the elements each startup must understand and be able to communicate | Settlement of Pitch for a selected group of investors and completion of Pitchbook |

Extension of the accelerator courses (selected startups). Alumni network for participants in Growth Train |

| Touchpoints | Growth Train website | Contract, intro day, first startup pitch, and meeting with a mentor | Course teaching, sparring with a teacher, meeting with mentors, working in a shared workspace, coaching in the ‘perfect pitch’, meeting with an advisor, customers, and partners, and excursion to companies and sites. | Demo day with investors and evaluation of personal growth and travel in 7 weeks sprint and service experience |

Invitations and activities in alumni networks |

|

|

Mentor/ teacher, etc. activity |

Program management and advisor assess applicants and convene interviews | Feedback to startup from a mentor, discussion of business idea and development needs, objectives for participation | Course presentations for several sprints on, e.g., visions, aspirations and branding, product-market fit and target group analysis, financial planning, communication and marketing, investor relations, preparation of ‘Pitch’, feedback from teachers and mentors, meetings with external advisors, and partners | Feedback from program management, teachers, and mentors on pitch and result of business development and prepared Pitchbook |

Book Contact between mentors and startups - including membership of “advisory boards” in respective startup companies. |

|

| Back stage | Program management, experts, and advisors | Program management and advisors decide on offers to participate in an accelerator program. | Meeting between program management, mentors, and teachers with an evaluation of participants' business ideas, competencies, and development goals |

Joint evaluation of course weeks and sprints with the participation of program management, teachers, and mentors. Adjustments in planned activities and the accelerator course. Administration and operation of the accelerator. |

Overall evaluation of Fast Track 2020 in a joint workshop with program management, lecturers, mentors, and researchers from Roskilde University |

Application to the Danish Business Authority for support for completing the Growth Train in 2021 and planning courses. |

An effective screening of potential participants and a goal-oriented selection of participants among 70 applicants gave a group of startups with sufficient motivation and commitment to participate in a 7-week intensive and accelerated sprint course. They have also taken part with a promise of significant learning outcomes. The so-called “why-definition” is the learning element that several participants mention. It means a heightened awareness among the participants about what difference their products and services make to the customers. The participants state that as an essential contribution to their learning in the accelerator.

In addition, the arranged meetings with potential customers and partners have been necessary for several participants. The meetings also gave participants insight into Denmark's highly regulated agricultural and food area. It probably provides high requirements for the validation of products and costs for expensive tests and trials before approval but is also a practical ‘steppingstone’ to the international market. Furthermore, it is an appreciation that teachers and mentors have possessed in-depth practical Experience and insight into a startup business. In addition, the participants have valued flexibility and diversity in the accelerator program. It has allowed them to focus on priority action areas as a startup company.

Finally, the completed program design with seven weeks of uninterrupted presence in Nykøbing Falster (Business Lolland-Falster) has been up for discussion among startups, teachers, and mentors concerning whether it could be broken up into smaller parts and distributed over a more extended period. There have been different attitudes to this depending on the needs and situations of the individual startups.

The Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) gives an empirical study and analysis of “Growth Train” as a business model with accelerated growth and development value proposition among international startups.

The Business Model Canvas for Growth Train shown in Figure 3, is based on data from an investigation into the Growth Train Accelerator (Møller et al. 2021), indicates how (“How”) stakeholders in the business ecosystem (including companies, investors, educational and research institutions, municipal authorities, and business promotion organizations), through the use of resources (money from the Danish Business Authority, teachers and mentors, local networks and social capital) and specific activities (content, structure, and governance) in the accelerator “produce” activities/services for the benefit of participating startups.

It also contains a value proposition for startups and stakeholders stating what (“What”) Business Lolland-Falster, as “owner” of the accelerator, can offer to satisfy their needs and challenges in connection with accelerated growth and development in both the individual startup company and the region. Educators and mentors are among the most important actors and resources for an accelerator because effective mentoring and sparring are among the most significant values an accelerator gives its startups (Bagnoli et al., 2020).

Business Model Canvas also states why (“Why”) it is necessary to think about revenue streams, as marketing, administration, operation, evaluation, and accelerator development involve several costs for Business Lolland-Falster as ‘owner’. So far, expenses are covered via a subsidy granted by the Danish Business Authority on the Finance Act. However, in the long run, they require new revenue streams (e.g., the involvement of larger companies and investors who can help lift Growth Train as an accelerator). It is thus income in the form of substantial grants. Still, the local community also benefits (‘revenues’) in contributions to economic growth and employment (Lolland-Falster).

Finally, the business model indicates who (“Who”) is the target group for the activity that the accelerator represents, namely international startups in the field of agriculture and food (a “strong position” in the region) and stakeholders who both contribute to and at the same time enjoying the activity. Also, through channels, the marketing reaches the selected target group (segmentation). It ensures a lasting connection to the customer segment (e.g., the Alumni Program for former participants in Growth Train).

Proposal for new development in the existing accelerator program

- Better branding of Growth Train as an attractive offer to the target group both locally and internationally, as attracting well-qualified startups is crucial for its reputation, the opportunity to acquire participants in the future and create growth and employment in the region.

- The ‘local relevance’ criterion must be tightened, and the screening process improved to achieve the best match between startups and Lolland-Falster's need for accelerated growth and employment.

- The accelerator design is adapted so that the qualities of the current seven-week intensive Fast Track course are maintained but possibly begin with a short-term boot camp, where more people are invited. Still, fewer go on in the actual accelerator course.

- Systematic offer of a couple of weeks follow-up on a completed 7-week sprint course after a few months to the startups that have shown an extraordinary potential for business establishment or collaboration with existing companies on Lolland-Falster.

- An extension of the accelerator course will strengthen the relationship with the business ecosystem. Current accelerator courses have proven too short to create more lasting connections between startups and the business ecosystem.

- A better understanding of the accelerator as a learning environment for startups - including what constitutes effective learning methods (Bliemel, 2014; Kolb, 1984; Miles, 2017) and the importance of diverse prerequisites, competencies, and situational factors (Lave & Wenger, 1991) for their business development.

Conclusions

The main conclusions the analysis and discussion of Growth Train as a startup accelerator have given in the previous addressing the research questions asked in the beginning are the following:

Firstly, the Growth Train, as an example of a startup accelerator, differs from more traditional incubation courses by being time-limited (in principle, it constitutes a 7-week sprint course), based on a selected group (cohort) of international startup companies with a specialized focus on agriculture and food. Driven by experienced mentors and educators, and concluded with a demo day for investors. Thus, no “Seed Money” is included in the course. The Growth Train accelerator is an authority-initiated accelerator that typically helps startups at a relatively early stage of their life cycle to stimulate entrepreneurial activities in the local ecosystem to create economic growth and employment in the local community.

Secondly, the analysis of Growth Train based on Service Design Thinking shows that it is an example of a ‘Service Journey’ (and a Startup Journey), where startups, through an accelerated 7-week sprint course, have quickly achieved a significant learning benefit with an increased focus on their customers and partners. It is especially true concerning what makes their products and services valuable for a specific target group of customers.

Thirdly, this consideration of the service journey as a suggestion of how startups create value for selected groups of their customers points out that Growth Train as an accelerator also represents a business model (including a value proposition) for a selected circle of startups. In addition, it is also for several partners and stakeholders in the local business ecosystem. The Business Model Canvas used shows that the accelerator thus offers startups a learning benefit and value offer that can enable them to scale up their Business and thus give them a more significant “flying height” and long-term survival. At the same time, stakeholders in the local ecosystem gain access to a value proposition that offers the opportunity for economic growth and employment for Lolland-Falster as an outlying area.

Finally, the evaluation of the accelerator process in 2020, together with further data and insights collected from the development of Growth Train in previous years, pointed to the need for several new developments in the existing accelerator design and its interaction with other business promotion initiatives on Lolland- Falster. Among other things, it is about a changed start on the accelerator with the possibility of a more efficient selection of participants for the subsequent 7-week sprint course, an offer of a supplementary course for selected startups with an extraordinary potential for establishment or collaboration with existing companies on Lolland-Falster and better integration of startup companies concerning the business ecosystem on Lolland-Falster as a whole.

Biography

Jørn Kjølseth Møller is an associate professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Business at Roskilde University in Denmark. His specialization is innovation, design, and entrepreneurship, and he has widely published in the field. He holds a Ph.D. from Roskilde University and a Masters in Design from the Royal Danish Academy.