Meaning Innovations with Design Support: Towards Transparency and Sustainability in the IT Field

Abstract

This interdisciplinary article views meaning innovations as socially constructed and reflects on designing in the context of potential harmful consequences within information technology (IT) contexts. In the shift from products towards services, digital platforms and technology designers have gained a mediating and more strategic role while developing multiple connections and interactions between products, touchpoints, users and suppliers. The design manager is involved in organisational strategizing and innovating. Following key principles of design, the context of all those affected by design should be considered. Meaning innovations may emerge when designers facilitate, partially guide and are guided by strategic goals and innovation discourses in organisational settings in conjunction with numerous others. Based on a literature review and reflection on empirical findings, this article suggests paths for designing meaningfulness through an exploration of material lifecycles, digital content, algorithms and data transparency in digital contexts. The concept of meaning innovation is suggested to encourage organisations to reflect on decisions regarding responsibility, sustainability and transparency beyond the mainstream customer focus leading to improved organizational sensemaking and decisions, supported by design.

Introduction

Fuzziness prevails not only at the front end of innovations, but also when design consequences are considered and organisational decisions are taken. Uncertain fluid contexts entail the risk of potential harmful consequences. This interdisciplinary article views designing as sensemaking and organisational context as the design space in which designers with other actors seek clarity on confusing issues. Given the increasingly strategic role of design (Borja de Mozota, 2017; Brown, 2009; Buehring & Liedtka, 2018; Liedtka, 2015), this article suggests incorporating the logic of meaningfulness (Dewulf et al., 2020) into the dialogue that design managers might initiate and support when embedded in industrial settings. The logic of meaningfulness could trigger more dialogue in which commercial and non-commercial actors with different professionals will together proceed towards more human and transparent insights informing organizational sensemaking and decisions.

Considering meaningfulness can clarify fuzzy consequences of design and production through micro-level enactments in sensemaking and lead to action with macro outcomes (Weick, 2011). Organisational phenomena construct a social sensemaking space enabling ongoing questioning about the sense of issues, such as potential harm to human beings or the environment. The fourth order of design (Buchanan, 2001, 2015) has led to a shift towards more communicative and interactive solutions in larger systems and environments, leading to new questions and concerns. These include recycling, new technologies, elaborate simulation environments, “smart” products, virtual reality, artificial life, and the ethical, political, and legal dimensions of design (Maguire, 2014). Yet, innovation research has barely studied the undesirable or unintended consequences of innovations (Lindell, 2016; Sveiby et al., 2012) while designers often work in innovation contexts (Hernández et al., 2018). By contrast, the design community has been concerned about such consequences for some time (Papanek, 1973; Penty, 2019). This article uses the concept of harmful consequences broadly when referring to consequences leading to potential negative outcomes during the production, use or after-use of services, systems or other design outcomes to any local, global or digital stakeholder (cf. Lindell, 2016; Mica, 2015).

This research sets out to discuss, through theoretical and empirical insights, how designers occupying managerial roles in mainly multinational industrial digital environments might address potentially harmful issues in their professional contexts, such as those in Silicon Valley, that employ digital technology in their global production of services and systems.

-

- RQ1:

-

- What kind of harmful consequences should be considered when designing in connection with information technology (IT)?

-

- RQ2:

-

- How might designers in the digital design environment support organisational sensemaking towards the creation of transparency and more meaningful decisions?

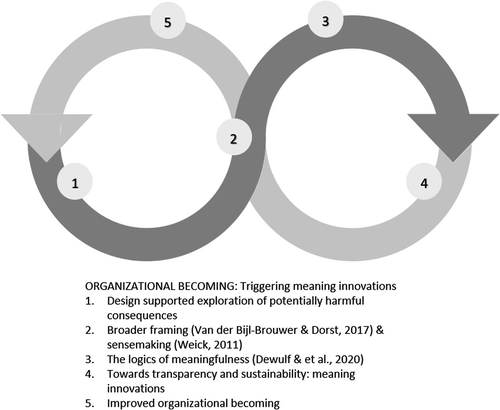

The research suggests four paths towards designing meaningfulness derived from potential harmful consequences discussed in the light of interdisciplinary literature (RQ1). The concept of meaning innovation in this context is suggested to support deeper organizational sensemaking towards more meaningful outcomes. Consequently, the discussion section suggests a model for triggering meaning innovations as part of organisational becoming (Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) and sensemaking (Weick, 2011) with the support of design (RQ2).

From the viewpoint of organisational becoming, organisational phenomena are enactments—unfolding processes (Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) in which actors interactively make choices in local conditions with the possibility of drawing on broader short- and long-term contextual issues and effects on third parties. The ongoing nature of organising design and making sense enables new kinds of micro initiatives, beliefs and stories. This research suggests that designers might utilise their ethos, skills and methods to fuel meaningfulness by examining potential harmful consequences derived from a broader frame (cf. van der Bijl-Brouwer & Dorst, 2017). By taking a more reflexive approach, this research seeks to establish a dialogue between paradigms and disciplines (Gioia & Pitre, 1990).

Methodology

This interdisciplinary article presents one cycle of analysis on a longitudinal research review seeking to understand designers in industrial digitalising contexts. Drawing on earlier notions of designers´ positive attitude and language this qualitative analysis focused on latent content (Graneheim et al., 2017) by seeking underlying themes related to potentially harmful consequences in the interview data. For abduction (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2018), theoretical insights and empirical findings were iterated prior to forming a model for meaning innovations as part of organisational becoming.

The University of Lapland collected interview data for which participants were reached through snowball sampling among existing networks in Silicon Valley-based design-driven organisations (Saunders & Townsend, 2018). The initial contacts enabled finding a sufficient number of design professionals with robust work experience (i.e., 10–20 years) with managerial roles as consultants or in-house designers at the time of the interviews. Most of the organisations were large multinational technology and manufacturing companies but two start-ups, two consultancies and one university visit were also included. Altogether, 16 interviews with 14 organisations, including one workshop and 20 recordings formed the recorded and transcribed data for analysis. The anonymised in-depth interviews (Johnson, 2002) were coded for identification and included discussions on current themes that the participants felt to be relevant in their design contexts. The codes used were: IT1-IT7 (information technology), S1-S2 (start-up), C1-C2 (design consultancy), E (education), U (user experience design workshop) and M (manufacturing industry).

Hermeneutics encourages deeper interpretations, such as considering presences and absences in the data. Following Tomkins and Eatough (2018), this article’s analysis aligns with the hermeneutic philosophy of understanding rather than focusing on numbers and categories. As the interviewees were not specifically asked about the harmfulness or transparency of production or design outcomes, the analysis has limitations. Despite this, since the participants were free to raise issues important for them spontaneously, the absence and presence of themes were suited to a hermeneutic approach; what was said or unsaid, and why, was of interest. The research focused on whether, how and to what extent potentially harmful issues were present or absent in the data and contrasted this with the literature in a theoretical frame.

The article discloses what is relatively absent (harmful consequences) and thus, less manifest in business innovation contexts (Sveiby et al., 2012). Such consequences could be potential triggers for meaningfulness among organisational actors supported by a more design-oriented way of making sense.

The article is not data-driven nor is it occupied with truth claims based on “facts” (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2018). Rather, reflexivity (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2018) raises issues that deserve timely attention. The examples drawn from interviews served as triggers for reflection. Reflexivity focuses on the context of design in the face of digitalising human lives and organisational sensemaking in industrial contexts.

Theoretical framework: deriving meaningfulness and transparency from harmful consequences

Fuzziness increases in direct proportion with design extending beyond a product-focused view. Buchanan (2001) described this movement as the fourth order of design: material objects not only have become communicative, but they are part of interaction as well as larger systems, cycles, and environments. New technologies (Maguire, 2014) have become embedded in everyday interaction worldwide, including “smart” products, virtual reality and artificial life, which has led to questions about the ethical, political and legal dimensions of design (Buchanan, 2001; van den Hoven, 2007). This research proposes that designers (as participants and facilitators in design-supported events) can support organisational actors in finding meaningfulness through the exploration of possibly unintended, yet harmful, consequences. This aligns with the principle of the organisational culture movement in design, which states those affected by corporate vision or strategies need to be considered when designing (Buchanan, 2015). Unintended harmful consequences are such that they may emerge at a future date or outside the direct environment in which decisions are made, such as the algorithm decisions of self-driving vehicles (Santoni de Sio & van den Hoven, 2018). The design community might increase design transparency and responsibility by providing improved online transparency or tools for the critical evaluation of health-related digital content (Lau et al., 2012). Design entails the desire to improve. Therefore, designers can support micro-processes of sensemaking (Weick, 2011) events in organisational becoming (Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) to influence meaningfulness and macro-level outcomes.

Sensemaking, as a framework, suggests that actors notice and select cues, interpreting them and attaching various meanings initiated by issues that require clarity (Weick, 2011). Hermeneutics is based on the idea that underlying assumptions shape the way some meanings are normally present in organisational sensemaking while other meanings (such as harmful consequences) may remain distinctly absent. Such fuzziness regarding consequences can be explored by means of diverse design approaches, such as designing for human wellbeing and sustainability (Desmet & Pohlmeyer, 2013; Penty, 2019), design ethics (Chan, 2018; Sweeting, 2018) or considering the trend that the digital world, through coding and ever-changing platforms, has become an ongoing test laboratory (Tonkinwise, 2016) of human interaction and worldviews. Manzini (2009) referred to a set of visions and reflections for stimulating and steering strategic discussions in a variety of projects. The purpose for the set was to help understand what people are doing or could do. In software engineering and systems development, “value sensitive design” (van den Hoven, 2007) studies how accepted moral values could be incorporated into IT design which has become a constitutive technology that shapes discourses, practices, institutions and experiences. Whether technology contributes to a good life (van den Hoven, 2007) or causes harm is one of the conversations that second-order cybernetics (second-order understanding) deems as necessary (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2015; Krippendorff, 2007). By iteration and broader framing (van der Bijl-Brouwer & Dorst, 2017), a more holistic understanding and consideration of effects on third party stakeholders may yield surprising insights and more informed decisions.

It is thus suggested that increasing awareness of potential harmful consequences constitutes an opportunity for designing meaningfulness. Moreover, Aguinis and Glavas (2019) linked corporate social responsibility to meaningfulness at work. Meaningfulness can also steer the strategic development of a sustainable business model (Ludeke-Freund & Dembek, 2017). Sustainable business model innovation has been combined with user-driven innovation (Baldassarre et al., 2017).

Expanding the scope means that the focus of user technology is expanded by exploring the entire production chain—locally, globally and digitally. Hence, the supply chain would involve not only immediate stakeholders, such as other businesses in networks, but also partners who take responsibility for their own and the focal organisation's stakeholders (Ludeke-Freund & Dembek, 2017). For example, mobile phones hide the less fabulous subjective meanings from the perspective of toxic waste and child labour. This is beyond surface-level beneficial outcomes for the producer of the device, the contents that attract users and the connectivity provided between the users. Harmful consequences may thus exist beyond the obvious and immediate. Pre-use and post-use stages of production are important. As Tonkinwise (2016) suggested, expert designers can engage in active problem-finding, sensing even possible failings if not actual failings; a code in Silicon Valley steers daily actions of most readers of this text regardless of location. Penty (2019) was concerned about the effects of Internet of Things, interconnected devices (Maguire, 2014) and increasing electronic waste. Introna (2007) discussed the ethics of information systems.

Chan (2018) stressed the need for ethics in the Anthropocene through three categories commonly encountered in design: technology, sustainability and responsibility. For Sweeting (2018), design and ethics can be mutually supportive and inform each other. Floridi (2016) reflected on how design might support beneficial behaviours; structural nudging changes the nature of the courses of actions available to an agent. Informational nudging, on the other hand, exposes the agent to information prior to reaching a goal, such as red warning signs. Designing entails striking a balance between paternalism and toleration. Santoni de Sio and van den Hoven (2018) developed the concept of meaningful human control for autonomous systems. Floridi (2016) suggested a pro-ethical design meant to educate agents to make their own critical choices and assume explicit responsibilities. Regarding value-sensitive design and sustainable innovations, the technology should first be shaped by constraints and aims, to the extent possible, rather than when technology is already in place (Santoni de Sio & van den Hoven, 2018). These authors suggested that an interactive service robot should be more responsive to a distressed patient in a healthcare setting than in a commercial setting. However, one might also question the need for interactive robots altogether in the face of more desirable human exchanges and unemployment threats. To make appropriate decisions, a person must deliberate about the consequences of actions (Noorman, 2020), yet justification towards action tends to be social (Weick, 2011) and partly inherited in practices and beliefs from earlier generations.

Design, being future-oriented, mediates between choices that it cannot determine on its own, neither can any single discipline make definite predictions about future events. While society-wide long-term changes are desirable, they are not ‘designable’ due to the numerous intertwined actions incorporating issues such as regulation, technology development or altered consumer practices (Hyysalo et al., 2019). Steps in this direction require collaboration across siloed entities such as companies, society, people, third parties, along with production and decision-making processes. An interesting perspective is offered by ‘intermediate designs’ in which the outcomes of codesign rather serve as ‘design seeds’ and ‘meta-designs,’ thus allowing users to further design (Hyysalo et al., 2019). ‘Intermediate designs’ are suggested to help participants reach meaningful outcomes in the face of high complexity and divergent participant perspectives. Such design seeds could be used as cues for broadening the scope of design in digital industrial contexts. However, many more design approaches strive to accommodate co-creation and joint sensemaking; for example, service design (Miettinen, 2017) and interaction design (Maguire, 2014) might use collaborative methods such as prototyping or journey mapping. Designing is a social effort with others.

Four areas of fuzzy, potentially harmful consequences of digital design environments were identified by scoping interdisciplinary literature related to IT production. In line with hermeneutics, by paying attention to relatively absent or rarely discussed harmful consequences in business decisions and by making them present, they can be utilised for collective reflection on meaningfulness in organisational strategising. While the examples below are not all-encompassing, they do cross disciplinary borders (Gioia & Pitre, 1990). They suggest possible paths towards designing meaningfulness. The four areas of harmful consequences are partly overlapping and serve as examples suggested to be useful for increasing meaningfulness in future-oriented reflections supporting organizational decision-making.

Harmful electronic devices

Possibilities exist for examining human exposure to harmful substances, from raw materials to components, including long-term effects (Penty, 2019). Physical touchpoints for third-party exposure can be mapped early on in new product development and improve existing conditions of workers in remote production locations. Harmful aspects include toxic materials, poor labour conditions, health effects or illegal dumping during material journeys. Highly toxic, rapidly increasing e-waste requires immediate attention (Ikhlayel, 2018), while effects on users deserve attention.

Designers might visualise, concretise and initiate multidisciplinary critical reflection to curb negative social and environmental effects. Caring for those exposed to toxic materials in their working conditions brings the problem at hand closer to both decision-makers and users of modern technology. Prendeville et al. (2013) illustrated how designers can explore material choices towards sustainability. As Glavas and Kelley (2014) proposed, employees find higher purpose by seeing how the organisation treats others.

Harmful digital content

Designers might examine suggested lifestyles in digital content that do not support health or well-being (cf. Lau et al., 2012). Rather than increasing consumption, design models could concretise the harmful consequences of consumption. Moreover, loading and streaming digital content radically increases global energy consumption (Morley et al., 2018).

Content with adverse effects on users could be problematised, thus preventing people from being influenced (Gunter, 2016). Non-digital solutions might increase well-being, such as face-to-face contact instead of ‘apps’. Humans need human interaction. Rather than adopting, unconsciously, ways of thinking in bubbles produced by codes, transparency of how codes produce what information is displayed to readers should be improved. Consumers need to be informed in order to decide how to spend their valuable time.

Algorithm decisions

Digital self-service increases and more work is taken over by customers. A digital service may imply the absence of personal service, yet sometimes be promoted as ‘service improvement’, such as at the airports.

Automated decisions may occur unnoticed, between algorithms, creating ethical problems. People might follow a blogger, assuming a human to be its creator. The ethics of innovations should be considered, such as the idea of robots improving social interaction skills with children (Huijnen et al., 2019). AI will replace human tasks when it performs tasks ‘better’ to meet a firm’s strategic goal, such as profit (Huang & Rust, 2018). One stream in AI research even argues that AI emotions are calculations similar to human emotions (Huang & Rust, 2018). Thus, children in the future might think like algorithms.

Design transparency

Data use should become transparent. New systems often contain hidden dangers which are very difficult to overcome later (Schaar, 2010). Relying on siloed expertise might ignore important issues. Awareness and ease of personal data control require improvement. Exploitation of user data jeopardises privacy. Transparency of cookie policy is an example of a time-consuming effort forcing the user to accept rather than make informed choices.

In sum, designers might support meaningfulness by clarifying and making collective sense of harmful consequences. One example, in which design is already recognised is sustainable business model innovation, including the creation of economic, social, and environmental value by collaborating with a wider range of stakeholders (Geissdoerfer et al., 2016). Innovators could identify possible negative effects early on and take corrective measures by considering all stakeholders (cf. Lindell, 2016). Design may facilitate the emergence of meaning innovations on micro-level enactments by providing sensemaking cues and frames with potential for macro-level impacts.

Figure 1 sums up the four areas of potential harmful consequences for designing meaningfulness. Pre-use and post-use stages are equally important areas to be considered and broaden the scope.

Interviews in Silicon Valley: absent and present themes

The four areas of potential harmful consequences for designing meaningfulness were used for extracting examples from designers in managerial roles in Silicon Valley. In general, the analysis found that the rationale (Dewulf et al., 2020) and language of business or engineering was adopted, but in combination with a search for future alternatives for meaningful outcomes. Much of the content the designers explained was about the methods they used in making sense of the situation of the client-user, the client-firm or other stakeholders. Orchestration in cross-disciplinary contexts led to the designers’ in-between position in organisational developments.

…improving the customers´ lives profoundly. (Participant IT4, 2013)

…if we’re designing for hospitals, we also have personnel and doctors involved. (Participant IT2a, 2013)

It´s more for like innovating social relationships of people, not about technology or engineering. (Participant IT7, 2016)

Taking into account all the human aspects in service deliveries, more than the hardware and software. (Participant IT3, 2016)

Yet, the designers were well-aware of the importance of the expected innovation outcome and the need for showing quick results, as this influenced the financial bottom line of the companies.

Strategic value, such as improved services, brand message or innovations, was generated through a genuine interest in the future and from a human perspective. There was enthusiasm and optimism (Michlewski, 2008) concerning the possibility of design improving the lives of people. To ensure customer delight, the design teams would empathise with the user. However, potentially harmful consequences (Figure 1) were barely mentioned. The focus stayed on the use stage rather than pre-use and post-use phases.

We can act as a catalyst that helps the company see itself and work together a bit better. (Participant C2, 2016)

Some design managers explained that they were advocates for the users, but they also involved people in their own organisations who would normally not have the opportunity to participate. Such people offered their knowledge in interdisciplinary teams.

Technology was embraced, without a doubt, to design social interactions and services. Participant C2 explained the difficulty in being involved later rather than sooner, leading to some features being lost in the end product. Material decisions of an interior, for example, limited the choices for placing digital installations leading to some user comfort being lost in the outcome. Such constraints were mostly found in less-than-optimal outcomes, sometimes due to lack of a budget. The desire to be involved early on and through the life of a project was expressed.

What you really want to do, is to enhance the employee experience, because this is a really crucial part of what comes out of the work. (Participant M, 2016)

…it’s a kind of double-bladed sword in a way. (Participant IT3, 2016)

Designers experiment with cognitive, emotional, digital and material elements and visualise options by seeking to understand human perspectives. However, against the theoretical suggestions, only a few notions were made regarding harmful consequences. Broader framing, and thus thinking about design outcomes, occurred mostly by including user or customer viewpoints or in efforts to change the conditions for employees. Transforming the business practices took place through educating other divisions by arranging co-creation activities. The environmental problems created by material waste, and thus sustainability problems (Manzini, 2009; Penty, 2019), were rarely mentioned. One participant (Participant IT3, 2016) reflected on PET bottles and the complexity and costs related to reuse. Few mentions were made about any harm caused by digital content, algorithms or data use in contrast to the reflection in the theoretical framework.

Discussion

Today, with increased awareness and knowledge about potential harm (Chan, 2018; Penty, 2019), designers in managerial roles may have the possibility of raising awareness of potential harmful consequences to be considered in organisational strategies. Therefore, it is suggested that the four areas of potential harmful consequences deserve more attention. As new ethical issues are anticipated, following Chan (2018), ethics is formative to the moral development of design disciplines in the Anthropocene. The same applies to organisational sensemaking and decisions.

Broadening the business and user-customer or employee context further could curb harmful consequences. Proactive organisations might reach meaning innovations through such discoveries. All those affected by design outcomes should be considered (Buchanan, 2015; Manzini, 2009), also in new technology developments. The article thus suggests the conceptualisation of meaning innovation as ‘designing for increased responsibility and design transparency with the help of extracting cues from existing or potential harmful consequences in local, global or digital lives of people involved in the production, use or disposal of what organisations produce in terms of materials, services or digital content’. Meaning innovation in this sense differs from the notions of meanings that are innovated in the technology innovation management frame (cf. Norman & Verganti, 2014) because the broader scope incorporates the potentially harmful consequences of innovations in the meaning exploration stages. Meaning innovations thus expand beyond customer experiences or technologies towards responsibility and transparency. Thinking about those exposed to the outcomes of digital developments can inform organizational decision making towards responsible choices.

As to ongoing sensemaking towards meaning innovations in organisational becoming (Tsoukas & Chia, 2002; Weick, 2011), design facilitates broader framing (cf. van der Bijl-Brouwer & Dorst, 2017) towards awareness of potential harmful consequences. With the help of design principles and methods, sustainable design or design ethics (to name a few), new meanings can be discovered and co-created. Figure 2 illustrates the iterative process of organizational becoming, with potential for meaning innovations. Through exploration of potentially harmful consequences supported by design approaches, the actors may use the logics of meaningfulness (Dewulf et al., 2020) in their sensemaking and collectively arrive at meaning innovations that are more transparent and sustainable. This, in turn, may lead to improved organizational becoming (Tsoukas & Chia, 2002).

As to the interview data, potential harmful issues seemed to remain absent while designing for pleasure (Sanders & Stappers, 2008) in the use stage was prioritised. However, designers may assume, without articulation, that tensions and problems exist behind all design. Internal struggles caused by professional situations and norms (Chan, 2018) may not surface easily in interviews and remain latent. The analysis has certain limitations. The interviews might have influenced the participants’ explanation about issues. The interviews focused mainly on the mutual interest in design methods, causing possible bias. The time for deeper reflection on consequences might have been too short. The interpretations by the authors are inevitably influenced by prior experiences in design and business fields. Silicon Valley forms a culture of its own and the research does not seek to generalize. Nevertheless, combined with theoretical insights and reflexivity (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2018), many ‘absent’ harmful consequences deserve more attention and form an area for further research.

Designers and managers could merge professional domains even further. Designers could provide cues for critical reflection on serious deeper long-term effects of digitally automated lives. This, it is suggested, will enable designers to initiate meaningful micro-level enactments in collective sensemaking through which macro-level phenomena become possible. For example, emergent strategies can evolve through the search for meaningfulness for all those affected by design in local, global or digital contexts. While literature indicates issues of harmful consequences to be important for future generations (Penty, 2019) and the generation of ethics and practices (Chan, 2018), the interview data is more ambiguous in terms of the direction of change desired in organisations.

Gradually, more holistically minded professionals might share the domains of technology and human sciences as a third way of knowing. This kind of knowing bridges paradigms and disciplinary borders (Gioia & Pitre, 1990). The logics of meaningfulness (Dewulf et al., 2020) could trigger more dialogue in which commercial and non-commercial actors with different professionals will together proceed towards more human and transparent approaches. Design education could contribute to enriching business and managerial perspectives where ethical consideration is needed (Chan, 2018). Designers might enhance local meaningfulness at work and global transparency and responsibility through the exploration of potential harmful consequences such as the four areas in the field of IT and electronic devices in this article.

Designers can be suited to initiate conversations (Dubberly & Pangaro, 2015; Penty, 2019) on meaningfulness not only concerning situated and commercial contexts but also concerning local and global transparency and responsibility throughout the product and service lifecycles. Due to their cross-functional orchestration between different stakeholders, they acquire holistic insights. If designers are involved sooner in the process, question the obvious or the absent, include third-party views and concretise and visualise harmful consequences, there might be opportunities for meaning innovations.

Design methods were discussed throughout the interview data supporting earlier research on the mutually supporting aspects of organisational cultures and design methods (Elsbach & Stigliani, 2018). Our findings may seem to support the notion that the organisational innovation frame is rather immune to considerations of harmful consequences which require time to reflect (Hasu et al., 2012).

Designing mediates between paradigms that can be conceived as transition zones (Gioia & Pitre, 1990). Design, organisation and management research might enhance meaningfulness through creation of interdisciplinary understandings on existing harm, leading practitioners and management to proactively consider harmful consequences. Bocken et al. (2016) provided an encouraging example on the circular economy.

There is a need for interdisciplinary education and holistic professionals who share the domains of technology, design and management and incorporate neglected issues of harmful consequences (Hasu et al., 2012; Lindell, 2016; Sanders & Stappers, 2008). Giloi and Quinn (2019) in their research noticed that there is an absence of explicit references as to how a curriculum aims to cultivate ethical and moral design practitioners. Dealing with harmful consequences could become a relevant agenda for further research, offering new avenues for studying meaning change and meaning innovation beyond consumer pleasure. Design research can contribute to critical management research and education.

The longitudinal research on designers working with new technologies requires further exploration for an enhanced understanding of design involvement and organisational sensemaking. Designers might examine the context of corporate social responsibility and design towards meaningfulness by drawing on the four starting points suggested in this article. By doing so, they might lead proactive organisations to meaning innovations.

Conclusions

From the viewpoint of organisational becoming, organisational phenomena unfold gradually in processes in which actors make choices interactively within local conditions and, as suggested in this article, with the possibility of drawing meaningfulness from broader contextual issues and potentially ‘absent’ harmful consequences on third parties locally, globally and digitally. The ongoing nature of organisational sensemaking, with design support, enables the emergence of micro-initiatives, new beliefs and stories. It is suggested that designers might utilise their ethos, skills and methods for fuelling meaningfulness by enhancing collective sensemaking and conversation on potential harmful consequences through broader framing. Meaning innovation as a concept entails that not only customers or other business stakeholders are involved but also the broader system and consequences behind any innovation.

Many fields of design connected with new IT have possibilities to proliferate towards meaningfulness. This article raised the issues of sustainability and design ethics, but many more design streams exist. Four starting points for designing towards meaningfulness were identified by considering potential and latent harmful consequences of products and contexts in the IT domain. Future designers, managers and educators will benefit from reflecting on such issues as part of their agenda by considering other stakeholders, especially those affected by design and production, locally and globally, in the context of new technologies.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to our peer reviewers. Business Finland funded the projects MediPro (2012–2013), HumanSee (2015–2016) and N4S (2014–2017) enabling data collection.

Biographies

Tarja Pääkkönen M.Sc.(econ), PhD Cand. at the University of Lapland combines design with organization and management studies. Intrigued by how designers think and how organizations make sense, her research focuses on organizational becoming and the in-betweenness of actors in sensemaking.

Dr. Melanie Sarantou is Adjunct Professor at the University of Lapland, investigating the role of arts, narrative practices and service design in marginalised communities. She currently coordinates a research project that investigates the role of art in marginalised communities across European countries.

Dr. Satu Miettinen is Professor of Service Design and Dean of the Faculty of Art and Design at the University of Lapland, Finland. For several years, she has been working with service design research. She has authored a number of books and research publications in this area.