Risk prediction of bladder cancer among person with diabetes: A derivation and validation study

Martin C. S. Wong and Junjie Huang are equal first authors.

Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to devise and validate a clinical scoring system for risk prediction of bladder cancer to guide urgent cystoscopy evaluation among people with diabetes.

Methods

People with diabetes who received cystoscopy from a large database in the Chinese population (2009–2018). We recruited a derivation cohort based on random sampling from 70% of all individuals. We used the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for independent risk factors to devise a risk score, ranging from 0 to 5: 0–2 ‘average risk’ (AR) and 3–5 ‘high risk’ (HR).

Results

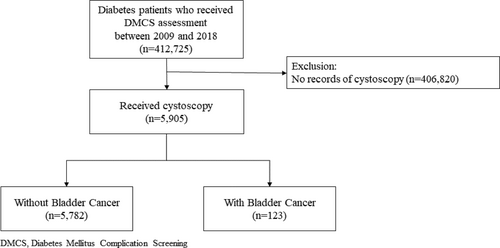

A total of 5905 people with diabetes, among whom 123 people with BCa were included. The prevalence rate in the derivation (n = 4174) and validation cohorts (n = 1731) was 2.2% and 1.8% respectively. Using the scoring system constructed, 79.6% and 20.4% in the derivation cohort were classified as AR and HR respectively. The prevalence rate in the AR and HR groups was 1.57% and 4.58% respectively. The risk score consisted of age (18–70: 0; >70: 2), male sex (1), ever/ex-smoker (1) and duration of diabetes (≥10 years: 1). Individuals in the HR group had 3.26-fold (95% CI = 1.65–6.44, p = 0.025) increased prevalence of bladder than the AR group. The concordance (c-) statistics was 0.72, implying a good discriminatory capability of the risk score to stratify high-risk individuals who should consider earlier cystoscopy.

Conclusions

The risk prediction algorithm may inform urgency of cystoscopy appointments, thus allowing a more efficient use of resources and contributing to early detection of BCa among people planned to be referred.

What's new?

- A 5-point risk score for prediction of bladder cancer was devised and validated based on participants' age, gender, smoking habits and duration of diabetes.

- The scoring system stratified people with diabetes into average risk (1.25%) versus high risk (4.07%) of bladder cancer with a good discriminatory capability (c-statistics: 0.72).

- Risk prediction of bladder cancer can allow resource allocation efficiently and early detection among people planned to be referred.

1 BACKGROUND

Bladder cancer (BCa) is one of the leading causes of cancer incidence and mortality.1 Globally, approximately 550,000 new cases are diagnosed annually and more than 199,000 BCa-related deaths were observed in 2018.2 The age-standardized rate (ASR) of BCa incidence varied widely, ranging from 1.3 per 100,000 in middle Africa to 26.5 per 100,000 in Southern Europe among the male populations. Similarly, a wide variation in ASRs of BCa incidence was also reported in women (0.8 in South Central Asia to 5.5 in Southern Europe).2 The ASR of BCa mortality was 3.2 in men and 0.9 in women. The past decade witnessed a decreasing trend of BCa incidence and an increasing mortality rate for both genders in Asian countries, North America, Oceania and South America; while its incidence was increasing and its mortality was declining in European countries.2 In Hong Kong, the ASR of BCa incidence and mortality was 3.1 and 1.1 in 2018.3 There were increasing incidence and mortality trends in both genders. According to the American Cancer Society, the overall 5-year survival rate was 77%. BCa is the most expensive cancer in the elderly population (estimated at US$4 billion per year), bearing the highest lifetime cost of treatment in people diagnosed with the disease.4, 5 The economic burden is further escalated by the adverse impact of BCa on mental health and quality of life among people with BCa.4

The majority (80%) of people with BCa present with painless haematuria. This could either be macroscopic or microscopic,6 and episodic or intermittent. In approximately 30% of people with BCa, the initial presentations may include irritative urinary symptoms. These include urgency, frequency, hesitancy and dysuria which are similar to that of urinary tract infection.7 Late symptoms and signs in invasive or metastatic BCa include pelvic fullness, urinary retention, flank pain, weight loss, bone pain and lower extremity oedema.7

Generally, cystoscopy and urinary cytology are commonly employed for diagnosing bladder cancer.8 However, the extended waiting times associated with cystoscopy can potentially impact people's access to timely medical consultations. Furthermore, there have been observational studies that focused on predicting the prevalence risk of bladder cancer in people with type 2 diabetes using national health databases.9, 10 It is worth noting that these studies did not develop a specific risk score for bladder cancer prediction. A systematic review11 reported 29 models for bladder and kidney cancer screening, in which all models contained haematuria, and with other components, such as additional symptoms (abnormal pain) and clinical features (biomarker). This study11 commented that only few models had been validated, while all experiment models had either high or unclear bias in the risk prediction section. Moreover, the Bladder Cancer Prognosis Programme (BCPP)12 and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk tables13 did not take the clinical factors of people with diabetes into consideration. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to develop effective and validated risk prediction models for bladder cancer in people with diabetes. This will enable timely identification of individuals at higher risk, facilitating early detection and intervention, and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

The aims of the present study are as follows: (i) to examine the independent factors associated with bladder cancer in people with type 2 diabetes suspected as having bladder cancer, as guided by a comprehensive literature search of its recognized risk factors; (ii) to devise and validate an algorithm for risk prediction of bladder cancer in these people by examination of its discriminatory capability; (iii) to evaluate the risk of bladder cancer in people assigned with different risk scores as predicted by the risk algorithm; and (iv) to estimate the resources needed to detect one bladder cancer in high-risk people with suspected bladder cancer when the scoring system is applied, based on the number needed to refer (NNR) for urgent flexible cystoscopy.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study setting

In this study, data were extracted from the Hospital Authority Data Collaboration Lab (HADCL), which is a platform providing access to an electronic healthcare database that consists of patient demographic data, clinical diagnoses, procedures, drug prescriptions and laboratory results from all public hospitals and clinics in Hong Kong.

2.2 Study subjects

We included all people with type 2 diabetes who have received flexible cystoscopy in the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong from January 2009 to December 2018, as documented in the database (Figure 1). Most of these participants presented with symptoms of bladder cancer, including gross haematuria, urgency, frequency, hesitancy and dysuria. For individuals who received more than one cystoscopy in the study period, we used findings from the earliest cystoscopy to avoid over-representation of a certain group of participants. The following ICD-9-CM codes were used to identify people with BCa: 188.0–188.9.

2.3 Derivation and validation cohorts

The proposed study included consecutively recruited symptomatic participants. We assume 25% as the point prevalence of individual risk factors and 0.2% as the prevalence of BCa in the derivation set. Based on these assumptions, a sample size of 1731 in the validation cohort could attain a power of >90% and detect a risk factor with an odds ratio of 2.0 at a significance level of p < 0.05.14 We examined the association between detection of BCa and each predictor in the derivation cohort using Pearson's chi-square test. We included the established risk factors for BCa in the general population, consisting of old age, male sex and smoking, as well as risk factors for many other cancers including obesity, alcohol drinking, duration of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and use of chronic medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], aspirin, metformin and insulin).15, 16

2.4 Development of the risk scores

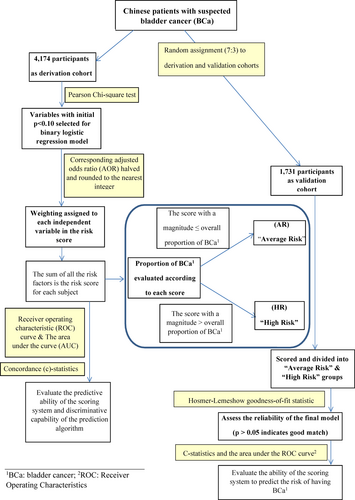

A multivariate regression analysis of all variables that predict BCa with statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis was performed. The outcome of the multivariate analysis was the cystoscopy detection of any BCa. We selected logistic regression models based on a stepwise approach. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were evaluated using all variables with significant predictive power, according to a binary logistic regression model trained from the derivation cohort. The risk scores were based on AORs halved and rounded to the nearest integer as in CRC risk scoring/in Figure 2. Although odds ratio/hazard ratio has been commonly used for deriving risk score,17, 18 due to its multiplicative nature, some have raised concerns over its use and suggested using regression coefficients instead.19 Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using both methodologies. Each individual person's score was the sum of the scores of the identified predictor variables, based on which we formulated a scoring algorithm that takes each weighted independent variable as an input. The algorithm's discriminatory ability was evaluated as the area under the curve (AUC) of the mathematically constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The actual predictive ability of the risk score was computed as the concordance statistic (c-statistic) (Figure 2).

2.5 Statistical analysis

For each score in the derivation cohort, the proportion of BCa was computed. Scores with magnitudes equal to or less than the average proportion of BCa were classified as ‘average risk’ (AR), whereas those with magnitudes exceeding the average proportion were assigned as the ‘high risk’ (HR) category. When the proportion of BCa for individuals with a particular score was close to the overall proportion, a cut-off score that provided a more precise risk estimate was selected. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was performed to determine whether an increase in the BCa proportion as a function of the risk score was statistically significant. We used the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistics to assess the reliability of the final prediction algorithm. As a statistical criterion, p > 0.05 indicated an acceptably strong relationship between the predicted and observed risks. The number needed to screen (NNS), defined as the inverse of the outcome probability predicted by the regression model, was evaluated as a measure of the prospective resource requirements if the scoring system was applied clinically to refer HR participants to urgent cystoscopy evaluation. The NNR for cystoscopy was calculated as the number of participants referred for colonoscopy divided by the number of participants referred for cystoscopy who have detectable BCa. All statistical effects with a two-sided p < 0.05 were deemed significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

The characteristics of the validation cohort were similar to those of the derivation cohort. (Table 1). Compared to people without bladder cancer, those with bladder cancer were more likely to be male sex (75.8% vs. 51.9%), in the oldest age group (36.3% vs. 17.7% were over 70 years old), smokers (ex/current) (48.4% vs. 32.2%) and have long-term diabetes (≥10 years) (42.9% vs. 32%) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Derivation cohort (n = 4174) | Validation cohort (n = 1731) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diabetes diagnosis in years, mean ± SD | 59.95 ± 11.49 | 59.75 ± 11.94 | 0.551 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n (%) | 2326 (55.7) | 988 (57.1) | 0.341 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 2187 (52.4) | 902 (52.1) | 0.841 |

| Current smokers/ex-smokers, n (%) | 1360 (32.6) | 550 (31.8) | 0.545 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 668 (16.0) | 280 (16.2) | 0.870 |

| Duration of diabetes in years, mean ± SD | 7.30 ± 7.54 | 7.56 ± 7.74 | 0.249 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2918 (69.9) | 1227 (70.9) | 0.456 |

| IHD/heart disease, n (%) | 471 (11.3) | 195 (11.3) | 0.983 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 373 (8.9) | 137 (7.9) | 0.203 |

| COAD, n (%) | 12 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 1.000 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 22 (0.5) | 14 (0.8) | 0.206 |

| Haematuria, n (%) | 910 (21.8) | 336 (19.4) | 0.576 |

| Use of NSAIDs, n (%) | 746 (17.9) | 332 (19.2) | 0.237 |

| Use of aspirin, n (%) | 368 (8.8) | 139 (8.0) | 0.326 |

| Use of metformin, n (%) | 793 (19.0) | 334 (19.3) | 0.792 |

| Use of insulin, n (%) | 180 (4.3) | 81 (4.7) | 0.532 |

| Bladder cancer, n (%) | 91 (2.2) | 32 (1.8) | 0.417 |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; COAD, chronic obstructive airway disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation.

| Risk factors | Without bladder cancer (n = 4083) | With bladder cancer (n = 91) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | Prevalence (%) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1965 (48.1) | 22 (24.2) | <0.001 |

| Male | 2118 (51.9) | 69 (75.8) | |

| Age at diabetes diagnosis in years | |||

| 18–39 | 170 (4.2) | n.p. (2.2) | 0.001 |

| 40–49 | 570 (14.0) | n.p. (6.6) | |

| 50–55 | 678 (16.6) | 13 (14.3) | |

| 56–60 | 672 (16.5) | 12 (13.2) | |

| 61–65 | 704 (17.2) | 14 (15.4) | |

| 66–70 | 565 (13.8) | 11 (12.1) | |

| >70 | 724 (17.7) | 33 (36.3) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| <25 | 1803 (44.2) | 45 (49.5) | 0.315 |

| ≥25 (obesity) | 2280 (55.8) | 46 (50.5) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 2767 (67.8) | 47 (51.6) | 0.001 |

| Current or past | 1316 (32.2) | 44 (48.4) | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 3428 (84.0) | 78 (85.7) | 0.651 |

| Yes | 655 (16.0) | 13 (14.3) | |

| Duration of diabetes | |||

| <10 years | 2778 (68.0) | 52 (57.1) | 0.028 |

| ≥10 years | 1305 (32.0) | 39 (42.9) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 1234 (30.2) | 22 (24.2) | 0.214 |

| Yes | 2849 (69.8) | 69 (75.8) | |

| IHD/heart disease | |||

| No | 3624 (88.8) | 79 (86.8) | 0.562 |

| Yes | 459 (11.2) | 12 (13.2) | |

| Stroke | |||

| No | 3720 (91.1) | 81 (89.0) | 0.488 |

| Yes | 363 (8.9) | 10 (11.0) | |

| COAD | |||

| No | 4072 (99.7) | 90 (98.9) | 0.233 |

| Yes | 11 (0.3) | n.p. (1.1) | |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| No | 4061 (99.5) | 91 (100) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 22 (0.5) | n.p. (0) | |

| Haematuria | |||

| No | 3190 (78.1) | 74 (81.3) | 0.466 |

| Yes | 893 (21.9) | 17 (18.7) | |

| Use of NSAIDs | |||

| No | 3352 (82.1) | 76 (83.5) | 0.727 |

| Yes | 731 (17.9) | 15 (16.5) | |

| Use of aspirin | |||

| No | 3725 (91.2) | 81 (89.0) | 0.460 |

| Yes | 358 (8.8) | 10 (11.0) | |

| Use of metformin | |||

| No | 3312 (81.1) | 69 (75.8) | 0.203 |

| Yes | 771 (18.9) | 22 (24.2) | |

| Use of insulin | |||

| No | 3907 (95.7) | 87 (95.6) | 0.797 |

| Yes | 176 (4.3) | n.p. (4.4) | |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; COAD, chronic obstructive airway disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

3.2 Independent predictors of BCa in the derivation cohort

From univariate logistic regression analysis, male gender (COR: 2.91, 95% CI: 1.79–4.72), smoking habit (ex/current) (COR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.30–2.98) and long-term diabetes (COR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.05–2.43) were significantly associated with BCa (Table 3). From binary logistic regression analysis, considering age as a binary variable (over 70 vs. 18–70) (AOR: 3.08, 95% CI: 1.93–4.91), male gender (AOR: 2.44, 95% CI: 1.42–4.19) and long-term diabetes (AOR: 2.22, 95% CI: 1.41–3.49) were significantly associated with BCa.

| Risk factors | Crude OR (95% CI) | L0 | L1 (final) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| Age at diabetes diagnosis in years | |||

| 18–39 | 1 | 1 | – |

| 40–49 | 0.89 (0.18–4.47) | 1.06 (0.21–5.34) | – |

| 50–55 | 1.63 (0.36–7.29) | 2.19 (0.49–9.91) | – |

| 56–60 | 1.52 (0.34–6.85) | 2.07 (0.45–9.42) | – |

| 61–65 | 1.69 (0.38–7.51) | 2.37 (0.53–10.71) | – |

| 66–70 | 1.65 (0.36–7.54) | 2.35 (0.51–10.92) | – |

| 18–70 | – | – | 1 |

| >70 | 3.87 (0.92–16.31) | 6.18 (1.42–26.95) | 3.08 (1.93–4.91) |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (obesity) | 0.81 (0.53–1.22) | – | – |

| Male sex | 2.91 (1.79–4.72) | 2.41 (1.40–4.16) | 2.44 (1.42–4.19) |

| Smokers/ex-smokers | 1.97 (1.30–2.98) | 1.25 (0.78–1.99) | 1.27 (0.80–2.03) |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.87 (0.48–1.58) | – | – |

| Duration of diabetes ≥10 years | 1.60 (1.05–2.43) | 2.44 (1.55–3.85) | 2.22 (1.41–3.49) |

| Hypertension | 1.36 (0.84–2.21) | – | – |

| IHD/heart disease | 1.20 (0.65–2.22) | – | – |

| Stroke | 1.27 (0.65–2.46) | – | – |

| Haematuria | 0.82 (0.48–1.40) | – | – |

| Use of NSAIDs | 0.91 (0.52–1.58) | – | – |

| Use of aspirin | 1.28 (0.66–2.50) | – | – |

| Use of metformin | 1.37 (0.84–2.23) | – | – |

| Use of insulin | 1.02 (0.37–2.81) | – | – |

| L0 | L1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Area under the curve (AUC) | 0.7492 | 0.7192 |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR, odds ratio.

- Results with bold values were statistically significant.

3.3 Development of the risk score

According to the AORs from the derivation cohort, the following variables were used to assign scores to each screening participant (Table 4): age 18–70 years (0) or above 70 years2; male gender1 or female gender (0); smoking habit (ex/current)1 or never (0); and duration of diabetes ≥10 years1 or <10 years (0).

| Risk factors | Criteria | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diabetes diagnosis, years | 18–70 | 0 |

| >70 | 2 | |

| Sex | Female | 0 |

| Male | 1 | |

| Smoking | Never | 0 |

| Current or past | 1 | |

| Duration of diabetes, years | <10 | 0 |

| ≥10 | 1 |

The scoring system ranges from 0 to 5, and a person's score was based on the sum of all the points allocated to each individual risk factor. Since the proportion of BCa prevalence for individuals with a score of 2 was close to the overall prevalence and a cut-off of 0–2 scores versus 3–5 scores provided a more precise risk estimate, a scoring of 0–2 was designated as ‘Average risk (AR)’ while scores at ≥3 were assigned as ‘High risk (HR)’ (Table 5). From this stratification, the prevalence of BCa was 1.57% and 4.58%, respectively, for AR and HR groups in the derivation cohort. Similarly, the prevalence of BCa was 1.25% and 4.07%, respectively, for AR and HR groups in the validation cohort. The sensitivity analysis shows that the scoring system based on beta-coefficient approach is comparable to that using odds ratios (Table S1 and S2).

| Score | Total number of participants, n | Participants with bladder cancer, n | Prevalence of bladder cancer (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1012 | n.p. | 0.2 | Average risk (AR) |

| 1 | 1079 | 21 | 1.9 | |

| 2 | 1231 | 29 | 2.4 | |

| 3 | 572 | 21 | 3.7 | High risk (HR) |

| 4 | 252 | 14 | 5.6 | |

| 5 | 28 | n.p. | 14.3 |

3.4 Validity and reliability of the model

The c-statistic for the risk score in the validation cohort was 0.72. We found that the best-performing scoring system in the validation cohort is a two-level (average or high) scoring system (OR = 3.26, 95% CI: 1.65–6.44). In other words, when risk is increased by one level on a two-level system, the likelihood of developing BCa is increased by 226%. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic evaluating the reliability of the validation set had a p > 0.05, implying a close match between predicted risk and real risk. The NNS and NNR were 26 (HR) and 80 (AR), respectively, highlighting the efficiency of the scores to detect one BCa by urgent cystoscopy (Table 6).

| Risk tier (risk score) | Derivation cohort | Validation cohort | Relative risk (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of participants, n | Participants with bladder cancer, n | Prevalence of bladder cancer, % (95% CI) | Total number of participants, n | Participants with bladder cancer, n | Prevalence of bladder cancer, % (95% CI) | ||

| Average risk (0–2) | 3322 | 52 | 1.57 (1.14–1.99) | 1362 | 17 | 1.25 (0.66–1.84) | 1 |

| High risk (2–4) | 852 | 39 | 4.58 (3.17–5.98) | 369 | 15 | 4.07 (2.05–6.08) | 3.26 (1.65–6.44); p = 0.025 |

| Total | 4174 | 91 | 2.18 (1.74–2.62) | 1731 | 32 | 1.85 (1.21–2.48) | |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Summary of major findings

A 5-point risk score for prediction of BCa was devised and validated based on participants’ age, gender, smoking habits and duration of diabetes. The scoring system could successfully stratify people with diabetes into average risk (1.25%) versus high risk (4.07%) of BCa with a good discriminatory capability (c-statistics: 0.72). Multivariate regression analysis was conducted for the selection of the model with the best goodness of fit to ensure the highest reliability. The NNS was small when the scoring system is applied to people with diabetes, indicating that its implementation could lead to more efficient use of cystoscopy.

4.2 Comparison of findings with existing literature

There are several recognized risk factors for BCa. Tobacco smoking has been considered as the most important contributing factor with an attributable risk of 50%,20 mainly due to carcinogenic substances like N-nitroso compounds and aromatic amines.21 From a meta-analysis of 83 studies, the pooled relative risk (RR) of BCa was 3.47 and 2.04, respectively, in smokers and ex-smokers when compared with non-smokers.20 Smoking cessation may reduce the risk of BCa development or progression,22 and there exists convincing evidence that the duration and intensity of smoking are significantly associated with a higher risk of BCa.23 From a global analysis performed by our team,2 tobacco smoking was found to be significantly associated with the ASRs of BCa incidence (r = 0.20 in men; r = 0.67 in women) and BCa mortality (r = 0.38 in men, r = 0.67 in women). Other important risk factors include: (1) older age; (2) male sex; (3) family history of BCa; (4) overweight or obesity as measured by the body mass index (BMI); (5) occupational exposure to carcinogenic chemicals; (6) dietary factors (low hydration, low intake of citrus fruit, cruciferous vegetables, vitamin A, folate and vitamin D); and (7) The presence of medical diseases such as diabetes9 and metabolic syndrome.24 Table S1 shows a list of risk factors for BCa from a systematic review of 279 full-text original articles16 and the limitations of the existing risk scores published thus far (Table S2).

The most common type of BCa is urothelial BCa, followed by squamous cell BCa. The cancer is further categorized into two distinct types, including non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC: 70%–85%) and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC: 15%–30%).6 In people with NMIBC, the cancerous cells are confined to the bladder mucosa or submucosa. This early stage could usually be managed by local treatment such as transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT), followed by intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy and regular cystoscopic surveillance. The prevalence of NMIBC is often higher and its natural history is relatively less aggressive.25, 26 The other one-quarter of people with MIBC will need more radical therapy, either by radical cystectomy or chemoradiation. In metastatic cases, they might only be treated by systemic therapy or palliative care.6 Early access to healthcare and sufficient provision of healthcare services are significant factors associated with early detection and better disease control in people with BCa in the long run.2 According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database maintained by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the American Cancer Society has reported the prognostic figures for BCa at different stages.27 The 5-year survival rate of BCa for people with in situ alone (96%) and localized (69%) disease stage is significantly higher than in people with regional (37%) and distant BCa (6%). Hence, prompt referral of people at high risk of BCa for more urgent workup is required, provided knowledge of the BCa risk for each person can be estimated.

Currently, flexible cystoscopy is indicated in the evaluation of macroscopic/microscopic haematuria, voiding symptoms, bladder or urethral fistulae/strictures and surveillance of bladder and urethral malignancies.28 While gross haematuria is widely accepted as an indication for cystoscopy, it remains controversial whether people with microscopic haematuria should be investigated given its high prevalence in the general population,29 wide variability of definitions (dipstick vs. urine microscopy and the level of positivity) and the low risk for urological cancer. There are different age thresholds and risk profiles where investigation is recommended, as stated in different international guidelines.29 For instance, the National Board of Health and Welfare of Sweden30 does not recommend cystoscopy in people with microscopic haematuria, while the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) proposed investigation of individuals with microscopic haematuria in people aged >60 years with either an elevated white cell count on blood test or dysuria.31 The American Urological Association (AUA)32 suggests investigations in people older than 35 years with ≥3 red blood cells per high-power field (HPF), whereas people aged <35 years could be referred for cystoscopy according to physician preference.

The heterogeneity of the recommendations highlights that there has been no consensus on who should receive urgent flexible cystoscopy among people with suspected BCa, as there is no assessment tool constructed in the general population available to estimate BCa risk and inform clinical practice. Previous risk algorithms for BCa prediction had a small sample size, were based on data from a small number of regions or included patients in Western populations which could limit the generalizability of the findings (Table S2). From the perspective of primary care physicians (PCPs), there has been no guideline or standard criteria where people with suspected BCa should be provided with urgent versus routine referral. In addition, both the PCPs and urologists will need to know the likelihood of people having BCa before arrangement of cystoscopy appointments, so as to assign high-risk individuals to urgent cystoscopy and average-risk people to routine cystoscopy. The absence of a scoring algorithm that could risk stratify individuals into average versus high risk for BCa represents a major knowledge gap for early identification of BCa while maintaining efficient utilization of public health resources.

The development of risk scores for bladder cancer among people with diabetes has remained limited. Among the available models, Tan et al's (2019) model exhibited the highest discriminatory power in external validation (AUROC = 0.77).33 This model combines factors like type of haematuria, age, sex and smoking status to predict bladder cancer risk. Notably, an optimized threshold yields a high sensitivity (0.99) but a lower specificity (0.31). Models incorporating urinary biomarkers showed promising performance, with Cha et al's (2012) models c and d exhibiting the best results (AUROC = 0.9).34 The models introduced by Loo et al,35 which consider factors like the severity of non-visible haematuria, demonstrated high discrimination. Specifically, Loo et al's (2013) model b exhibited notable external validation results (AUROC = 0.809). It is worth noting that established prognostic tools like the Bladder Cancer Prognosis Programme (BCPP)12 and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk tables13 did not incorporate the clinical aspects unique to people with diabetes. In light of this gap, our study contributes significantly by offering valuable, effective and validated risk prediction models specifically tailored for bladder cancer in people with diabetes. This innovation enhances the potential for timely identification of individuals at heightened risk, thereby facilitating early intervention and detection, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

The predictor variables and cystoscopy outcomes were based on objective data obtained from the computerized system, which has been proven to have a high level of completeness and accuracy in our prior evaluations.20 However, several limitations should be noted. Firstly, despite the fact that each participant recruited in this study was not known to have experienced any BCa symptoms, these complaints might not have been entered into the computer system since they could have been included in the free-text consultation notes. Nevertheless, this dataset has previously been validated and was found to have a very high level of completeness (99.98%). In addition, we did not consider other recognized risk factors of BCa which were taken into account in some other studies conducted in resource-intensive, hospital settings. Collecting these parameters during clinical consultations requires validated questionnaires which are time-consuming, and therefore may not be feasible in busy clinical settings. Given the advantages of different methodologies, it is essential to conduct further comparisons to identify the most suitable method for developing risk scores.19

4.4 Conclusions

We devised a validated clinical scoring system for prediction of BCa among Chinese people with diabetes. The risk prediction algorithm may inform urgency of cystoscopy appointments, thus allowing a more efficient use of resources and contributing to early detection of BCa among people planned to be referred. We recommend the score to be validated externally before applying to other population groups with different demographic characteristics. Future research could evaluate whether the scoring system is feasible, acceptable, cost-effective and the proportion of reduction in advanced BCa when implemented in clinics and the community.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Martin C. S. Wong participated in conceiving the study and project administration. Eman Yee-Man Leung and Sarah T. Y. Yau contributed to the data curation and statistical analyses. Martin C. S. Wong and Junjie Huang drafted the manuscript. Harry H. X. Wang, Jeremy Y. C. Teoh, Peter K. F. Chiu and Chi-Fai Ng reviewed and revised the manuscript. Junjie Huang was the correspondence for journal submission.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our gratitude to the Hospital Authority Data Collaboration Laboratory, which provided the research team access to the territory-wide electronic health record system in Hong Kong.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The present study was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used for the analyses are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.