Healthcare professionals' experiences in identifying and supporting mental health problems in adults living with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study

Abstract

Aims

To explore perspectives and experiences of healthcare professionals in the identification and support provision of mental health problems in adults living with type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Using a qualitative research design, 15 healthcare professionals working in the United Kingdom were individually interviewed using a semi-structured interview schedule. Data were analysed using reflexive inductive thematic analysis.

Results

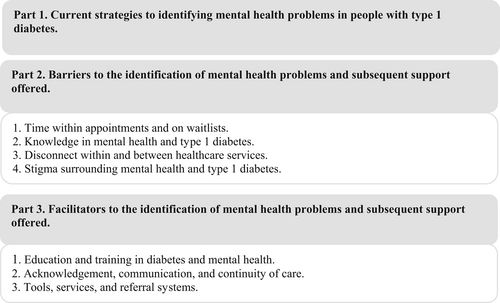

Four themes were identified relating to barriers: time, knowledge, relationship between services and stigma. Three themes were identified relating to facilitators: education, communication and appropriate tools and services.

Conclusions

This research emphasises the need for educational tools to improve the skills and competency of healthcare professionals in identifying mental health problems in people with type 1 diabetes, highlighting practical and theoretical implications for healthcare improvements and the necessity for additional research to design care pathways that better support this population, in which all healthcare professionals are aware of.

What's new?

- Barriers for healthcare professionals (HCPs) to the identification of mental health problems were identified including time, knowledge, relationship between healthcare services, and stigma.

- Facilitators included education, communication, and appropriate tools and services for referral.

- With psychological support as a priority in diabetes care, it is essential that HCPs receive adequate training to identify mental health problems and are aware of referral pathways and services.

1 BACKGROUND

Self-management of type 1 diabetes is the foundation of diabetes care. It involves constant vigilance and multiple self-care tasks, such as checking blood glucose levels, counting carbohydrates, and calculating and injecting insulin doses multiple times a day. Despite effective insulin regimens, diabetes technologies and structured education, the burden of self-management remains psychologically demanding.

Research has consistently shown that mental health problems are more common in people living with type 1 diabetes than in the general population.1, 2 These problems can present as diabetes distress and/or mental disorders and are often more prevalent in people with suboptimal glycaemic control.3 The interaction between diabetes and mental health problems presents a major clinical challenge, as this co-morbidity leads to worse outcomes for both conditions.4, 5 An individual's quality of life is worse, diabetes self-management is impaired, the incidence of complications is increased, and life expectancy is reduced.5

Over a decade ago, Diabetes UK released a report and position statement highlighting the importance of integrating psychological support in diabetes care on a national level, and aimed to provide recommendations for NHS England, Health Education England, and healthcare professionals (HCPs) for better diabetes care.6 Despite national and international guidelines recommending regular screening, up to 45% of cases of mental disorders go undetected among people with diabetes.7-9 Previous research has highlighted the current roles of HCPs in increasing access to mental healthcare for people with type 1 diabetes.10, 11 Focusing primarily on type 2 diabetes, qualitative research has highlighted HCPs need a better understanding of the impact of chronic illnesses on individuals' mental health.12

This study aims to explore the experiences of HCPs identifying and supporting mental health problems in people living with type 1 diabetes.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

A qualitative design using individual semi-structured interviews was employed. This study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines, a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups (see Appendix A).

2.2 Participants and recruitment

Purposeful sampling was employed with the aim to recruit diverse HCPs involved in delivering care to people living with type 1 diabetes (i.e. GP, practice nurse or diabetes specialist). HCPs were contacted through existing clinical networks across a southern region of England. Study documents including a participant information sheet and contact details of the study team, were distributed to potential participants. The research team arranged interviews with HCPs who contacted the team directly.

2.3 Data collection

A semi-structured interview schedule was developed, which allowed for standard questions to be asked across interviews, but permitted topics of interest to be probed further.13 N = 15 individual interviews were conducted between 28 August 2021 and 18 January 2022 by a researcher (MB) and clinician (SL). N = 2 participants requested in-person interviews which were conducted by SL. The remaining (n = 13) were conducted online by the first author (MB). Interview times ranged between 11 and 52 minutes (mean time = 25 min).

With participants' consent, interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.14 Confidentiality was maintained by allocating each participant a study number and all potentially identifying features were removed from the transcripts. Data collection concluded when data saturation was achieved, and no new themes emerged from the data. All authors agreed that data saturation was met at the 14th interview and one additional interview was conducted. Lastly, in recognition of the researchers' potential to influence the interpretation of results, self-reflexivity14 was engaged throughout the research. Our team consisted of individuals from diverse clinical and research backgrounds including psychology, psychiatry, general practice and diabetology.

2.4 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted from NHS Health Research Authority (Reference: 20/PR/0839).

2.5 Data analysis

Interview data were analysed using reflexive inductive thematic analysis. The analysis process followed the six steps outlined by14, 15: (1) data familiarisation through transcribing, reading and re-reading the data; (2) generating initial codes from across the dataset; (3) searching for themes by collating related codes; (4) reviewing themes in relation to both coded extracts and the entire dataset, and creating a thematic map; (5) defining and naming themes and (6) writing up the final results. Transcripts were coded by the first author (MB), initial themes were developed by two authors (MB and JB) and then discussed and refined with all authors. A final thematic structure was achieved through ongoing discussion between the authors with all authors agreeing on the final themes.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

Participants were n = 15 HCPs including n = 1 healthcare assistant, n = 4 diabetes specialist nurses, n = 1 practice nurse, n = 2 diabetes specialist registrar, n = 1 acute medicine consultant, n = 1 diabetes specialist consultant, n = 3 general practitioners (GPs), n = 1 GP trainee. HCPs had varied lengths of experience in their roles from 2 months to 41 years (Table 1).

Results are presented in three parts: (1) current strategies to identifying mental health problems, (2) barriers to the identification of mental health problems and subsequent support offered and (3) facilitators to the identification of mental health problems and subsequent support offered. Four themes were generated in relation to barriers and three themes were generated relating to facilitators (see Figure 1). These themes are presented below together with excerpts of supporting data.

| Participant ID | Role | Years in current role | Gender | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Healthcare assistant | 7 years | Female | 23 years |

| P2 | Community diabetes specialist nurse | 41 years | Female | 69 years |

| P3 | Community diabetes specialist nurse | 15 months | Female | 31 years |

| P4 | Diabetes specialist nurse | 3.5 years | Female | 39 years |

| P5 | Diabetes specialist nurse | 20 years | Female | 54 years |

| P6 | Diabetes specialist registrar | 6 years | Female | 36 years |

| P7 | Specialist nurse | 21 years | Female | 59 years |

| P8 | Acute medicine consultant | 7 years | Female | 50 years |

| P9 | Diabetes registrar | 2 years | Male | 30 years |

| P10 | Practice nurse | 6 years | Female | 53 years |

| P11 | Diabetes specialist consultant | 2.5 years | Male | 48 years |

| P12 | General practitioner | 28 years | Male | 58 years |

| P13 | General practitioner | 20 years | Male | 50 years |

| P14 | General practitioner | 3 years | Female | 31 years |

| P15 | General practitioner trainee | 2 months | Female | 31 years |

1 Part 1. Current strategies to identifying mental health problems for people with type 1 diabetes

HCPs discussed two primary means of identifying potential mental health problems: first, through enquiries about general or emotional well-being and second, through individual's HbA1c and diabetes management.

I … try and start the consultation with a very open question about how they are and make it very clear that it's a question about how they are not how their diabetes is. Sometimes people might start answering the question to do with diabetes, and then I'll say “No, how are you … we're going to talk about diabetes but how are you doing?” (Diabetes Specialist Registrar, P6)

Sometimes I think something might be going on if I look at their blood results and they're telling me a picture that doesn't match up with what I'm seeing with the numbers. (Diabetes Specialist Registrar, P6)

If their HbA1c is 48 or something excellent … sometimes they're the ones I worry about most. Because if you kind of go hiking 30 times a day, you're going to burn out and I'm sure I'll see them back in two years' time and they'll be exhausted from the diabetes. So, it's those ones that we don't pick up on at all (Diabetes Registrar, P9).

2 Part 2. Barriers to the identification of mental health problems and subsequent support offered

Four main barriers to identification and subsequent support offered were identified. These related to time, knowledge, relationship between services and stigma.

2.1 Theme 1. Time within appointments and on waitlists

Time was raised by all HCPs as a barrier and was related to time they had with patients to discuss mental health and second, the length of waitlists for patients who required additional care.

It won't be a 5-min conversation … I get quite a lot of time with my patients, and I still struggle to get through all the things that I want to go through with them … bring mental health into that, that could potentially take longer … There is a fear that if your clinic's running late and you say ‘hey and how are you doing?’ And then they burst into tears. It's like it [the clinic] will be running really late now (Diabetes Specialist Consultant, P11).

Sometimes there's this pressure to … cover everything regarding diabetes … the physical side of managing like the injection sites, checking blood glucose levels … if you're then talking about how someone's mood has been, sometimes there's that fear that my goodness I'm not going to cover everything that I needed to do in the diabetes clinic (Specialist nurse, P4).

The sad thing is you refer people to get help they then say ‘well there aren't any appointments for six months’. When people have mental health issues, they need that help now not in six months' time (Specialist nurse, P5).

There is often big waiting lists for counselling unless you're going to pay for it privately … It's a challenge and you do feel a bit down and despondent in some ways in that you know you can't just book them an appointment the next week (Specialist nurse, P7).

2.2 Theme 2. Knowledge of mental health and type 1 diabetes

I don't feel like I'm really equipped to have those conversations because I've never had that training (Specialist nurse, P3).

We didn't have any training … it's generally what I've experienced in previous roles … I've learned a lot of the things along the way by speaking to people who are living with these conditions (Specialist Nurse, P4).

Sort of feeling awkward talking about it … worry about quite what to do with it if you unearth an issue. You have to assess that risk and what to do about that: Are they high risk? What sort of assessment should you be doing? Are you worried about suicide and things like that? Are they OK to go home? (Diabetes Specialist Consultant, P11)

It is difficult because I'm not massively confident when it comes to mental health. I've never had any training. (Community diabetes specialist nurse, P3)

2.3 Theme 3. Disconnect within and between healthcare services

There isn't really a proper system that you feel that ‘OK. I have put this patient on that track and I'm happy that his mental health is going to be dealt with.’ (Acute medicine consultant, P8)

‘I don't want to talk to anyone else’. I've heard that a few times: ‘I don't want to keep going over my story. I don't want to keep saying this to different people. It's not getting me anywhere’. I have heard that before and I guess that's when joining them [services] would be really useful. Like having a link nurse between the physical or mental health teams (Specialist nurse, P4).

If people are coming to us and saying, ‘do you know what, I'm going to be open and honest …’ And then we kind of go ‘oh, that's great, but we don't really know where we can send you’ … it's not giving the patients best care (Specialist Nurse, P3).

I think they don't know where to access help and have to jump through so many hoops to get that help … I think that's probably the biggest barrier that they just don't know where to go and then how to access it (Specialist nurse, P3).

People are finding it really difficult just to communicate with their primary care. They feel they can't get through to their GP … I think that might be another barrier in that it's not so easy to access your GP…just getting through on the telephone is difficult (Specialist nurse, P7).

Mental health teams … seem to get a bit nervous if someone has a chronic medical problem, so they will often refer back to us. Because the mental health part may be understood but they get slightly panicked by a chronic medical problem … so I think it makes it more complicated trying to access the services (GP, P12).

2.4 Theme 4. Stigma surrounding mental health and type 1 diabetes

Mental health still has a stigma attached to it and no matter how much people try to remove that stuff it's still there. So, they're living with one chronic condition already and if you try to potentially diagnose them with another diagnosis I think there can be reluctance (GP, P12).

May be the barriers they perceive are that doctors in diabetes or diabetes specialists only really care about their blood sugars and the numbers. I don't know whether it's from past experience but they think that all we want to hear about is their good numbers and good readings and think we'll tell them off. So I think they come into clinic and expect to have a conversation about their blood sugars, not about their mental health. (Diabetes Registrar, P9).

3 Part 3. Facilitators to the identification of mental health problems and subsequent support offered

Three themes were generated relating to facilitators of the identification of mental health problems and support offerings.

3.1 Theme 1. Education and training in diabetes and mental health

There is a real need for training the whole workforce, because otherwise all that's going to happen is you're going to put layer upon layer upon layer of different sorts of healthcare professionals and the poor person with diabetes getting pushed (Specialist nurse, P2).

We have lots and lots of education and training around the medications that we use… and how to conduct consultations and how to get the best effective time out of what you're doing. But I feel like maybe we need to delve into how and when those questions are asked, how do you direct the patients? (Community diabetes specialist nurse, P3).

3.2 Theme 2. Acknowledgement, communication and continuity of care

Just being open as a clinician to talking about it is probably the first and most important step, because given the opportunity, I think people are quite eager to talk about that element of their care. So if you obviously don't provide it, it will never come up … So if it's at least flagged routinely as part of diagnosis, this support is available…I think just encouraging people that it's normal and it's appropriate to seek support as much as we can. (GP trainee, P15)

Acknowledging that the diagnosis has a significant psychological impact … psychological well-being can improve control. So preparing people for it when they had the diagnosis, saying actually we need to be providing you with holistic care to manage a chronic condition (GP, P13).

If we've known the patient for a long time and the patient feel more comfortable with the staff who seeing them or their health care professionals seeing them, they might feel a little bit more comfortable bringing it up. (Acute Medicine Consultant, P8)

Relationships are so important because if you haven't built that trusting relationship, and you don't really know the person that you're seeing…it takes a lot of time to be able to build that trust, and for someone to recognise as well when things aren't going so great for you. (Specialist nurse, P4)

3.3 Theme 3. Tools, services and referral systems

…a possible intervention would be a pre clinic questionnaire that would flag up mental health issues so you aware to discuss them when you saw them in clinic. (Diabetes registrar, P9)

In the GP setting there are prompts so obviously your annual review of diabetes in routine checks… if one of those is always to check-in for mental health concerns and coping and then just to make it as readily accessible as possible … I think if you're having your annual review, that is a really valuable opportunity to touch base… to talk someone every year or every six months. (GP trainee, P15)

I think getting the mental health care when they need it, in a timely way. I think if you're feeling depressed, you need help now, you don't need help in three months' time… like you would if you break your leg you get it straight away, wouldn't you? (Specialist nurse, P7)

We should never just refer someone with type 1 diabetes to psychologist or mental health team that doesn't have experience in type 1 diabetes. So, I think there is something around a team of people that have psychological or mental health skills that understand how type one diabetes symptoms and management overlap, how they merge, how they you know if you already got a self-harming type of character, personality trait whatever that might be… I think that that other barrier is shared knowledge (Specialist nurse, P2).

4 DISCUSSION

We conducted individual semi-structured interviews with HCPs to understand their experiences and views of mental health care for people with type 1 diabetes. The study aimed to identify facilitators and barriers for HCPs in identifying and supporting mental health problems in people living with type 1 diabetes.

Importantly, all HCPs recognised and acknowledged the impact of type 1 diabetes on mental health outcomes and the need for care to be improved. Numerous barriers were identified by HCPs including time constraints, knowledge of mental health and type 1 diabetes, relationship between healthcare services and stigma. Several HCPs were reluctant to engage in conversation due to perceived lack of skills, lack of time and access to further support services. Notably, similar barriers were reported in a study examining emotional support for people living with type 2 diabetes.16

A lack of knowledge and education was a fundamental barrier identified by HCPs. These findings highlight the need to design a brief educational intervention for HCPs who are engaged in care for people with type 1 diabetes to ensure that they have the skills, competency and subsequent confidence in identifying mental health problems for people with type 1 diabetes. This has been supported by previous research that training HCPs in psychological skills has a positive effect on care outcomes.17 These education programmes could include components of stigma reduction interventions which were raised by HCPs as a barrier to care and have been identified by people with diabetes as having considerable consequences for management and care received.8 Diabetes UK published a handbook to guide HCPs support the emotional needs of people with diabetes.18 However, our study shows that HCPs require additional training to complement this resource particularly around stratification of severity of mental health disorders.

Also relevant to the study findings, is work by two of the authors (HP and KI) who were lead editors of Royal College of Psychiatrists Liaison Faculty & Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS): guidelines for the management of diabetes in adults and children with psychiatric disorders in inpatient settings which outlined the limited evidence base.19 Despite a focus on psychiatric disorders in inpatient settings, multi-level suggestions were made for improving training including integrated commissioned models, patient-structured education, acute trusts to develop joint pathways with mental health providers to facilitate multidisciplinary working, screening for mental ill health in those admitted with acute complications of diabetes whose aetiology is unclear or not medically explained. It was also suggested that clinical teams should ensure that all staff can access training in diabetes and mental health to support them to care for people with both diabetes and severe mental illness, develop local pathways for joint working and ensure best practice tariff criteria are met for diabetic ketoacidosis and hypoglycaemia, and for children and young people with diabetes. Findings provide important information to further evaluate and design care pathways to best support people living with type 1 diabetes. It should be acknowledged that strategies to manage medical and psychiatric morbidities will depend on the category of mental disorders, severity and its interaction with diabetes self-management and glycaemic control. One methodology for this could be a two-stage survey design to first screen for mental disorder and second to conduct diagnostic interviews to understand prevalence and care received by people with type 1 diabetes.20

4.1 Strengths and limitations

We believe this is the first study to provide insight into the multifaceted experience of identification and support of mental health problems for people living with type 1 diabetes from HCPs perspectives. We included HCPs with varying roles and years of experience to ensure different perspectives were considered.

HCPs who agreed to participate are likely to have a special interest and more awareness of the interface between mental and physical health in diabetes. Therefore, there may be some unaddressed barriers and facilitators such as other HCPs may lack interest in mental health or do not consider it as relevant to their clinical remit. Participants were also recruited across only one region of England and therefore results may not be generalisable to other areas of the UK. Recruitment was difficult potentially reflecting workforce challenges in the NHS.

5 CONCLUSION

The study provides insight into the multifaceted experience for HCPs in identifying and supporting mental health problems for people with type 1 diabetes. The findings highlight the need for educational tools to improve the skills, competency and confidence of HCPs in identifying mental health problems for people with type 1 diabetes. Additional research is necessary to evaluate and design care pathways to better support people living with type 1 diabetes and mental health problems, that all HCPs in contact with this population are aware of.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all the healthcare professionals who participated in this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

APPENDIX A

A.1 COREQ: a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups.

| No | Item | Guide questions/description |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||

| Personal characteristics | ||

| 1 | Interviewer/facilitator | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? |

| 2 | Credentials | What were the researcher's credentials? E.g. PhD, MD |

| 3 | Occupation | What was their occupation at the time of the study? |

| 4 | Gender | Was the researcher male or female? |

| 5 | Experience and training | What experience or training did the researcher have? |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| 6 | Relationship established | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? |

| 7 | Participant knowledge of the interviewer | What did the participants know about the researcher? e.g. personal goals, reasons for doing the research |

| 8 | Interviewer characteristics | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? e.g. Bias, assumptions, reasons and interests in the research topic |

| Domain 2: Study design | ||

| Theoretical framework | ||

| 9 | Methodological orientation and Theory | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? e.g. grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis |

| Participant selection | ||

| 10 | Sampling | How were participants selected? e.g. purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball |

| 11 | Method of approach | How were participants approached? e.g. face-to-face, telephone, mail, email |

| 12 | Sample size | How many participants were in the study? |

| 13 | Non-participation | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? |

| Setting | ||

| 14 | Setting of data collection | Where was the data collected? e.g. home, clinic, workplace |

| 15 | Presence of non-participants | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? |

| 16 | Description of sample | What are the important characteristics of the sample? e.g. demographic data, date |

| Data collection | ||

| 17 | Interview guide | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? |

| 18 | Repeat interviews | Were repeat interviews carried out? If yes, how many? |

| 19 | Audio/visual recording | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? |

| 20 | Field notes | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? |

| 21 | Duration | What was the duration of the interviews or focus group? |

| 22 | Data saturation | Was data saturation discussed? |

| 23 | Transcripts returned | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? |

| Domain 3: Analysis and findings | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| 24 | Number of data coders | How many data coders coded the data? |

| 25 | Description of the coding tree | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? |

| 26 | Derivation of themes | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? |

| 27 | Software | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? |

| 28 | Participant checking | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? |

| Reporting | ||

| 29 | Quotations presented | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? e.g. participant number |

| 30 | Data and findings consistent | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? |

| 31 | Clarity of major themes | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? |

| 32 | Clarity of minor themes | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? |