Pathogenic variants in chromatin-related genes: Linking immune dysregulation to neuroregression and acute neuropsychiatric disorders

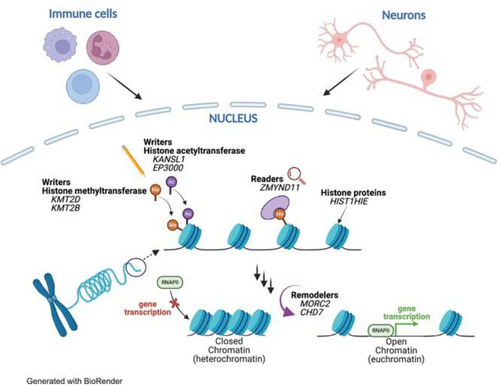

Even though every cell in the body has the same DNA, different genes are turned on or off depending on the cell type. This allows cells to perform specialized jobs, like helping the brain process information, or the immune system fight infections. These changes in gene activity are controlled by a process called epigenetics, which acts like a switch to regulate gene function without altering the DNA itself. One key part of this process involves chromatin, a structure that helps organize DNA. Changes in genes related to chromatin can affect how cells function and may lead to complex health conditions that impact multiple organs.

We report on eight children who had genetic DNA changes in these chromatin-related genes. All of these children experienced a sudden worsening – a ‘regression’ of their neurodevelopmental condition after an infection or other immune triggers. Some lost social and language skills, while others developed new psychiatric symptoms like obsessive-compulsive disorder, tics, or severe anxiety. We also found that several children had a history of immune system problems, such as frequent infections or autoimmune conditions. One key finding was that these chromatin-related genes are active not only in brain cells but also in immune cells. This suggests that changes in these genes may make the immune system react differently to infections, which could then impact brain function.