Human milk and breastfeeding during ketogenic diet therapy in infants with epilepsy: Clinical practice guideline

Abstract

Ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) is a safe and effective treatment for epilepsy and glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency syndrome in infancy. Complete weaning from breastfeeding is not required to implement KDT; however, breastfeeding remains uncommon. Barriers include feasibility concerns and lack of referrals to expert centres. Therefore, practical strategies are needed to help mothers and professionals overcome these barriers and facilitate the inclusion of breastfeeding and human milk during KDT. A multidisciplinary expert panel met online to address clinical concerns, systematically reviewed the literature, and conducted two international surveys to develop an expert consensus of practical recommendations for including human milk and breastfeeding in KDT. The need to educate about the nutritional benefits of human milk and to increase breastfeeding rates is emphasized. Prospective real-world registries could help to collect data on the implementation of breastfeeding and the use of human milk in KDT, while systematically including non-seizure-related outcomes, such as quality of life, and social and emotional well-being, which could improve outcomes for infants and mothers.

What this paper adds

- Human milk and breastfeeding can be incorporated safely into ketogenic diet therapy.

- With expert guidance, human milk and breastfeeding do not reduce diet effectiveness.

- We show two strategies for clinical practice to include human milk.

- Mothers can be encouraged to continue breastfeeding.

What this paper adds

- Human milk and breastfeeding can be incorporated safely into ketogenic diet therapy.

- With expert guidance, human milk and breastfeeding do not reduce diet effectiveness.

- We show two strategies for clinical practice to include human milk.

- Mothers can be encouraged to continue breastfeeding.

Abbreviations

-

- GLUT1

-

- glucose transporter type 1

-

- KDT

-

- ketogenic diet therapy

Ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) is a well-established treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy, glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency syndrome, and specific epilepsy syndromes such as infantile epileptic spasms syndrome in early infancy.1-4 Data have shown that KDT is feasible, effective, and safe in this age group.5-11 Readily available ketogenic formulae have facilitated the introduction of KDT in young infants before the introduction of solid food, when compliance is higher. Compared with older children, dropout rates are lower,4 treatment duration is shorter (between 10 and 13 months),5 and effectiveness rates are high. However, randomized controlled trials in this age group to demonstrate efficacy in specific epilepsy syndromes and aetiologies are rare and urgently needed.12 A recent randomized controlled trial has shown that KDT was as effective as antiseizure medication in drug-resistant epilepsy in this age group.13 This study showed that the odds ratios of achieving seizure freedom after 8 weeks and improving communication, socialization, and overall health scores were slightly higher in the group receiving KDT than in that receiving antiseizure medication, with a similar proportion experiencing at least one serious adverse event.

Current guidelines on KDT in infants8 suggest a gradual introduction and individual escalation of ‘classic’ KDT with a fixed fat:non-fat ratio to a maximum of 3:1. Fasting and fluid restriction are not advised in this age group.9, 14, 15 The fat:non-fat ratio can be adjusted according to the clinical condition of the child and the individual ketosis level. Consequently, lower fat:non-fat ratios allow higher carbohydrate intake which can facilitate the inclusion of human milk and breastfeeding into KDT.16

However, current international guidelines8, 9 do not contain recommendations for including human milk and breastfeeding as part of KDT, in contrast to other diseases such as phenylketonuria or other inborn errors of metabolism.17-19

Human milk is considered the ideal food and criterion standard for newborn babies. On the basis of the proven short- and long-term benefits of human milk and breastfeeding both for the infant and for the mother, the American Academy of Pediatrics reiterated its recommendations in 2022: ‘Exclusive breastfeeding for approximately 6 months, followed by continued breastfeeding with the introduction of complementary foods, continued for 1 year or more, each, as desired by mother and infant’.20-22 These recommendations are in line with those of the World Health Organization23 and its current guideline. The aim is to give increased support to health-care facilities that provide maternity and newborn-baby care, to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding.24

Given the lack of recommendations on the inclusion of human milk and breastfeeding in KDT, our aim was to provide practical recommendations based on expert consensus. Our methods associated a narrative review completed by an international survey about the inclusion of human milk in infant KDT.

METHOD

A working group of five experts (ADre, EvdL, PT-S, SA, JHC: i.e. three paediatric neurologists and two registered dietitians) already involved in the ketogenic diet guidelines for infants with drug-resistant epilepsy8 met online to discuss issues arising from the clinical management of breastfed infants on KDT.

On the basis of the limited data already published, the survey was conducted rather than a Delphi panel to base our expert opinion on current clinical practice more than consensual opinion. Similar approaches have been used previously for expert consensual recommendations on the use of KDT in infants8 and the parenteral administration of KDT.25

Literature review

A narrative review of the literature was conducted using the National Library of Medicine. Three searches were done using the following keywords: ‘breastfeeding AND ketogenic diet’, ‘human milk AND ketogenic diet’, and ‘breast milk AND ketogenic diet’, last updated on 5th April 2023. Search queries ‘human milk AND ketogenic diet’ returned fewer results (n = 7) but completely overlapped with search ‘breast milk AND ketogenic diet’, so we used results from search ‘breast milk AND ketogenic diet’. However, we decided to use the standardized term ‘human milk’ throughout the text, as recently suggested.26 English-language articles were included as there were no articles found in other languages (as of 30th January 2024). Abstracts were screened to identify any original papers on the use of human milk during KDT in infants. The selection process for the papers included in this review is shown in Figure S1.

International survey

An international survey consisting of an online questionnaire in four languages (English, French, German, and Italian) was distributed to an international group of dietitians and paediatric neurologists by Matthews Friends UK, the Ketogenic Diet National Working Group of Netherlands/Flanders, the Ketogenic Diet Network of German-Speaking Countries, the Ketogenic Dietician Research Network of the UK, and the ‘Ketogenic ListServ’. Conducting an international survey allowed the experts to base their recommendations on facts more than by collecting consensual opinion from a Delphi panel that might be disconnected from daily clinical practice.

The digital surveys sent in 2021 and 2023 (updated shorter version) are included in Appendices S1 and S2. The first questionnaire consisted of 22 questions on patient type, indications, diet composition, diet application, ketone levels, outcomes, benefits and challenges of human milk use, reasons for discontinuing KDT, and maternal diet. The second questionnaire consisted of five questions on KDT indications, dietary application, and maternal diet.

Practical recommendations

The literature review and survey responses were used to formulate an expert consensus about practical recommendations for the inclusion of human milk and breastfeeding in KDT. The expert group comprised the authors of this paper.

RESULTS

Narrative review of literature

Five original papers reporting the use of human milk in KDT for infants were found (Figure S1). These included three clinical case series of infants treated by KDT including human milk,27-29 one comparative study of infants treated by KDT including human milk compared with infants not fed human milk,16 and one case report of a lactating mother who underwent KDT herself, introduced gradually, to treat her infant who had drug-resistant epilepsy with ketogenic human milk.30, 31 Detailed data are shown in Table S1.

International survey

Survey participants

On the basis of the small number of infants on KDT with human milk (n = 35) reported in the literature, we expected the experience with the use of human milk during KDT to be limited. Thirty-six expert centres from 17 different countries (Austria, Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, France, Chile, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands, UK, and USA) participated in the first survey, and 28 expert centres from 12 different countries participated in the second (Austria, Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Chile, France, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, the Netherlands, UK, and USA). The number of respondents varied for each individual question.

Frequency of breastfeeding during KDT

Almost half of the centres (16 out of 36) reported having access to a specialized human milk nurse on their team, nearly two-thirds of respondents (20 out of 36) estimated that the proportion of infants using human milk during KDT treatment was lower than the average breastfeeding rate in their country, on the basis of personal experience, while one-third (11 out of 36) estimated that it was similar and two considered it higher (2 out of 36).

PRACTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE USE OF HUMAN MILK DURING KDT IN INFANTS

In this section, for each item the results from the literature review and the surveys are followed by a summary and recommendations for clinical practice.

Patient selection: patient characteristics

Literature

The indications for KDT in infants have been detailed in previously published guidelines as well as a consensus paper8, 9 and have remained unchanged over the past decade. KDT remains the sole causative treatment for GLUT1 deficiency syndrome and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency. The reported application of KDT for drug-resistant epilepsy in infants is mainly in the treatment of infantile epileptic spasm syndrome,8, 9 although this is rapidly expanding to include infants with other developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. There are few reports of newborn babies and very young infants7, 32-34 and, so far, these reports are consistent with effective and safe use; however, no new evidence has emerged. As previously stated in other guidelines, before initiating KDT, children should be screened for conditions for which KDT is contraindicated.8, 9

Survey

Across all centres, a median of 17 children (range 1–50) older than 12 months and a median of four infants (range 0–20) younger than 12 months started KDT per year. Across 18 centres, a median of one neonate (range 0–6) started KDT, eight centres started from birth, three centres at 2 weeks, and seven centres at 4 weeks. The second survey (n = 28, 2023) showed that four centres started KDT in one to six newborn infants per year. The main reason given for not choosing KDT was the lack of transfer/opportunity.

Reasons for not introducing KDT in neonates are listed in Table 1. Table 2 shows aetiologies/indications for KDT in newborn babies and infants younger and older than 3 months.

| Reason | Number of respondents, n = 36 (2021) |

|---|---|

| Never had cases with such indications/neonatal patients are taken care of in another area of the hospital | 18 |

| Not often thought/unaware that ketogenic diet therapy in neonates is a possibility | 2 |

| Lack of indications for the neurologist | 2 |

| First attempts with other antiseizure medication | 2 |

| Usually need to perform genetic tests/other investigations and see whether medication alone helps | 1 |

| Risk of hypoglycaemia, difficulties of management with breastfeeding | 1 |

| Missing case numbers | 1 |

| In general (n = 36) (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Epilepsy syndrome/aetiology | Respondents |

| Epilepsya before 3 months of age | 24 |

| Epilepsya between 3 and 12 months of age | 33 |

| PDHc or GLUT1 deficiency before 3 months of age | 30 |

| PDHc or GLUT1 deficiency after 3 months of age | 32 |

| Before 3 months of age (n = 32) | |

| Epilepsya | 25 |

| GLUT1 deficiency | 7 |

| PDHc deficiency | 4 |

| Refractory status epilepticus | 1 |

| After 3 months of age (n = 35) | |

| Epilepsya | 34 |

| GLUT1 deficiency | 5 |

| PDHc deficiency | 4 |

| Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome | 1 |

- Abbreviations: GLUT1, glucose transporter type 1; PDHc, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex.

- a ‘Epilepsy’ includes the following answers: epilepsy, generalized seizures, Dravet syndrome, Ohtahara syndrome, refractory epilepsy, infantile spasms/West syndrome, refractory epileptic encephalopathy.

Summary

The results of the surveys, which largely reflect previous KDT guidelines8, 9 and our current literature review, indicate infrequent use in neonates owing to lack of indication or opportunity, as neonates are often cared for in other hospitals or referred to other hospitals for epilepsy management beyond the neonatal period.

Both surveys report the use of KDT in infants in well-established indications. GLUT1 deficiency syndrome and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency remain important conditions where KDT is currently the only treatment to deliver adequate energy to the brain.

Recommendations

A comprehensive evaluation should be performed when considering KDT, particularly in newborn babies and early infancy. Age-related epilepsy syndromes35 are mainly determined by aetiology, so specific treatments may be particularly effective, such as certain antiseizure medications for genetic channelopathies (e.g. sodium channel blockers for KCNQ2 or for SCN8A developmental and epileptic encephalopathy). As reported in the past, KDT can be used in infants with a good balance of benefits and risks. The use of human milk or breastfeeding does not change the clinical indications or contraindications for the use of KDT.

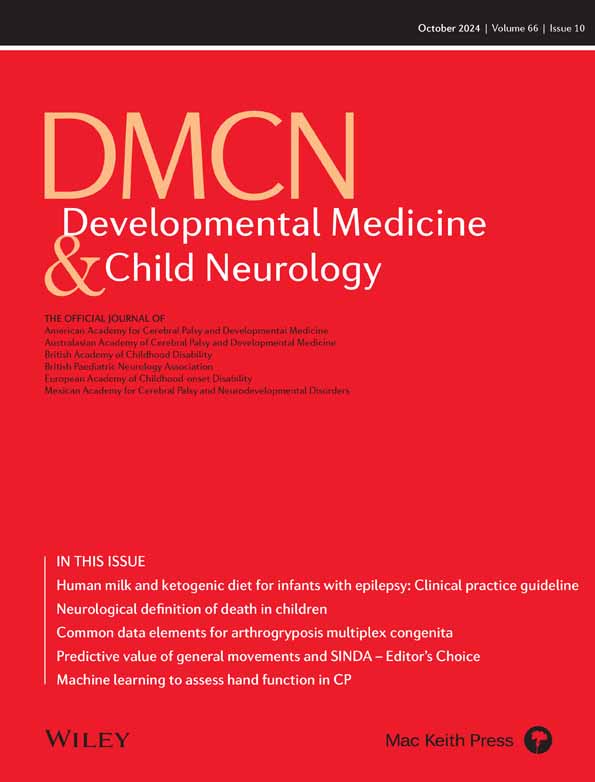

Preparing/motivating the mother

The mother's motivation and desire are fundamental to the continuation of human milk or breastfeeding during KDT. However, even the decision of early breastfeeding depends on the time, resources, and support of healthcare professionals for breastfeeding counselling.36 Experts must therefore emphasize very clearly that weaning from human milk/breastfeeding is not required when initiating KDT. Pro and contra of using expressed human milk mixed with KDT formula or of using KDT formula followed by natural breastfeeding are listed in Figure 1, along with practical recommendations in Figure 2. This should be discussed with the mother before initiation of KDT.

Maternal diet and supplements

It is not common practice to advise the mother to follow a modified Atkins diet or any other type of carbohydrate-restricted diet to achieve ketosis in breastfed infants. However, healthy eating patterns and supplements are generally recommended during breastfeeding to meet increased needs.37

Literature

To date, only one case report has described the effectiveness of maternal KDT in controlling seizures in breastfed infants, along with analysis of the nutritional composition of the maternal human milk30 and description of maternal diet regimen31 (Table S1). However, several publications have reported life-threatening adverse events due to severe ketoacidosis when mothers started KDT as a weight loss lifestyle while breastfeeding.38-44 In these studies, maternal dietary regimens were not well described. The authors therefore urgently warn against a carbohydrate-reduced diet during breastfeeding.

Survey

In 2021, only 2 out of 36 experts recommended maternal dietary changes, either a carbohydrate-restricted diet or low glycaemic index treatment; this result was repeated in the survey in 2023 (2 out of 28).

Summary

Well-documented information on the safety and effectiveness of maternal KDT while breastfeeding, for both infant seizure control and maternal dietary composition, is scarce. Maternal KDT has yet to be studied in detail. An example of a safe way to introduce KDT in breastfeeding mothers could be the ‘low and slow’ method of Fabe and Ronen.31 Future studies are required and should include analysis of human milk.

Recommendations

Maternal dietary changes should not be initiated without medical and dietary advice from a team of experts who are aware of the potential adverse events. This should only be done in a gradual and controlled manner if the infant is not seizure free on KDT combined with human milk.

Dietary composition

Ketogenic diet composition in infants

The international guideline published in 2016 provides recommendations for the optimal management of KDT in infants (Table S2).8 The use of human milk or breastfeeding during KDT does not change the guidelines for infants.

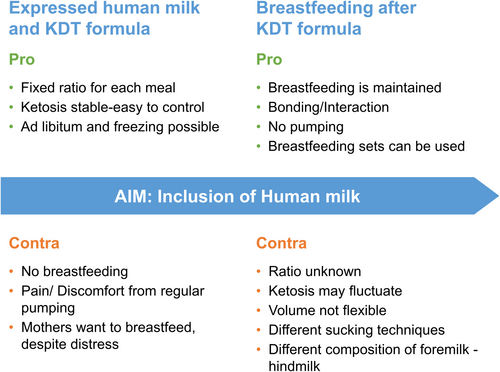

Ketogenic diet composition in infants using human milk

There are two possible methods for KDT calculation: using diet composition based on human milk analysis or using average human milk composition (Table S3).

Literature

There is a lack of literature on the analysis of human milk in the context of KDT, and detailed information on nutritional data is sparse, as human milk depends on various factors such as maternal eating habits45 and infant age.46, 47 Only one case report30 systematically analysed human milk (Table S1). Two studies used average macronutrient reference values of human milk,16, 28 and one described this as moderately reducing the KDT ratio (range 2.1–2.5),16 which may also be true when human milk was not calculated in the prescription.27, 29 When breastfeeding was included (n = 5),16 human milk volume was calculated by initial weighing before and after breastfeeding and/or counting time (minutes) per breast side. Ketosis was measured 1 hour after breastfeeding.

Survey

Nutritional composition of human milk

In 2021, only one centre analysed the macronutrient composition of human milk; centres on the whole instead assumed average values for human milk using multiple reference values (e.g. Souci and Fachmann, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization, Ketocalculator, McCance and Widdowson, NEVO, Milkbank). Only one centre reported analysing human milk macronutrient composition, when difficulties were encountered (achieving ketosis, problems with growth, or inadequate seizure control).

Ketogenic diet ratio at start and during maintenance

In 2021 (n = 36), half of all centres started KDT in infants with a ratio of 1:1 to 2:1, 10 used a ratio between 2:1 and 3:1, and only three started with a ratio of 3:1 to 4:1. However, 22 centres did start with a lower KDT ratio than that previously stated in the questionnaire. In neonates, KDT ratios were usually lower at baseline: nine centres started with a 1:1 to 2:1 ratio, only three with a 3:1 to 4:1 ratio, and only one centre started with a 4:1 ratio. Nine centres also started with the previously stated ratio.

During maintenance, four centres reported using ratios between 3:1 and 4:1, while three used lower ratios on an individual basis (lowest possible ratio to achieve adequate levels of ketosis).

In 2023 (n = 28), ratios adopted in infants were even lower: 12 of the respondents reported ratios from 1:1 to 2:1, while another 12 used ratios of 2:1 to 3:1. Only one centre reported an individual approach according to the specific infant. This was also true for KDT use in neonates in 2023, as four centres used KDT ratios ranging from 1:1 to 2:1, two centres used ratios ranging from 2:1 to 3:1, and only one centre reported a ratio between 3:1 and 4:1.

Summary

Detailed information on nutrient composition while using human milk during KDT is scarce owing to limited data on human milk analysis and difficulties in measuring human milk volume when breastfeeding is supported. Average reference values from different sources are mainly used for expressed human milk. Current guidelines for infants recommend KDT ratios up to 3:1. In our surveys from 2021 and 2023, a trend towards lower ratios has been observed for infants and neonates. In the literature, only one study16 reported that KDT including human milk with modified ratios (below 3:1) is equally effective and safe while ensuring age-appropriate protein intake for growth.

Recommendations

(1) For diet calculation, the recommendations from the infant guidelines should be used. (2) A moderate KDT ratio ranging from 2:1 to 3:1 is recommended to allow adequate protein intake for growth and to facilitate use of human milk and breastfeeding. Lower or higher ratios can be used on an individual basis. (3) Standardized values for expressed human milk should be used for nutritional calculations (see, for example, Gidrewicz and Fenton;46 Lawrence et al.;48 Jenness;49 Ballard and Morrow;50 Wu et al.51). (4) A nutritional analysis of human milk is recommended when insufficient ketosis, seizure reduction, or growth occurs to add nutritional supplements and improve KDT individually.

Using human milk during KDT

Advantages of using human milk

Literature

Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for infants for the first 6 months after birth21-23 by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization, as is the introduction of complementary foods along with breastfeeding for infants from 6 months to 2 years and beyond.

Breastfeeding carries unique physiological benefits for both the infant and the breastfeeding mother.52-55 Besides promoting optimal growth and development,55 breastfeeding has prospectively been linked to higher scores on neurological and cognitive tests later in life.56-59 Moreover, breastfeeding seems to reduce the risk for childhood epilepsy,60 to prevent infectious diseases, and limit the onset of some chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity53, 54 (Table 3).

| Reduced risks for the infant | Reduced risks for the mother |

|---|---|

| Gastro-intestinal tract infection | Immediate benefits after birth (e.g. reduced bleeding, postpartum weight loss reduce stress) |

| Respiratory infection, asthma, hospitalization for respiratory infection | Type 2 diabetes |

| Otitis media | Cardiovascular risk |

| Cognitive development | Breast cancer risk |

| Sudden infant death syndrome | Ovarian cancer risk |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | Visceral adiposity |

| Obesity | |

| Epilepsy in childhood |

Survey

Table 4 shows the survey (2021) data ranking the benefits of using human milk during KDT. The highest scores were obtained for fulfilling mother's wishes and for bonding with the mother over any other medical reason.

| Advantage | Rankinga |

|---|---|

| Mother's wish | 1 |

| Bonding with the mother | 2 |

| Fewer infections | 2 |

| Helpful for coping with episodes of intercurrent illness | 4–5 |

| Less constipation | 5–7 |

| Adequate ketosis despite lower KDT ratio and more carbohydrates allowed | 6–8 |

| Fewer adverse effects during initiation | 7 |

| If KDT is not effective, breastfeeding can be continued | 3 and 8 |

- Abbreviation: KDT, ketogenic diet therapy.

- a 1, most important; 8, least important.

Profile of human milk in KDT

Studies have shown differences in the composition of human milk at the beginning (2–3 minutes, foremilk) and the end of breastfeeding (hindmilk).61, 62 Hindmilk contains a higher concentration of fat, energy, and vitamins,61, 63, 64 but different lipid profiles of foremilk and hindmilk have only recently been studied.65 Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry has shown that the fat concentration in hindmilk was almost twice that in foremilk (120.6 ± 66.7 μmol/mL vs 68.6 ± 33.3 μmol/mL). Analyses indicated that the lipid profile of human milk also reflected individual characteristics of the mother. However, data on the use of different parts of human milk during KDT treatment are not available and reference values include average data, hence including both foremilk and hindmilk.

Survey

Twenty-seven centres used both hindmilk and foremilk, while two used only hindmilk and one only foremilk.

The only centre analysing human milk composition did this only when experiencing difficulties, not routinely. Sixteen respondents did not add any supplements to improve the composition of human milk. Eight respondents added maternal vitamins, breastfeeding supplements, ketogenic formula, vitamin D, or human milk fortifiers. Eleven centres did not respond to this question.

Twenty-two centres had access to a (national) human milk bank, but only six used human milk from a human milk bank in case of shortages.

Recommendations

Currently there is no clear evidence of a clinical advantage using hindmilk rather than foremilk, although differences in lipid composition might suggest a theoretical advantage for hindmilk. This topic needs further research.

Application of human milk: different strategies of clinical practice

Motzfeld et al.17 were the first to use human milk in infants with inborn errors of metabolism. They successfully developed a strategy whereby children diagnosed with phenylketonuria (those with phenylalanine blood levels below 1200 μmol/L) were breastfed at every meal after drinking a large amount of protein-free formula. This was based on the idea that, depending on the volume of the bottle, infants adjust the amount of human milk they drink: the more volume in the bottle, the less human milk is ingested. This strategy of using human milk in infants with inborn errors of metabolism has proved to be very convenient. Adjustments based on laboratory values can be easily made by adjusting the bottle volume. In addition, it promotes the bond between mother and child, as breastfeeding continues. This strategy was replicated in the guidelines for phenylketonuria and for other inborn errors of metabolism,18, 19 but has not been widely implemented in KDT practice.

Literature

As described in the literature review (Table S1), different strategies of administering human milk have been reported.16, 27-29 These included (1) mixing expressed human milk with ketogenic formula;28, 29 (2a) bottle-feeding ketogenic formula before breastfeeding (n = 5),16 (n = 1);27 (2b) alternating ketogenic formula both three to four times daily with breastfeeding, beginning with breastfeeding followed by ketogenic formula (n = 2).27

Survey

Nineteen centres included human milk into KDT only for infants, 11 centres included human milk both for infants and for newborn babies, and five did not include human milk in either age group.

Eighteen centres initiated KDT when infants and newborn babies were breastfed, while 11 did so only for infants. Six centres did not initiate KDT during breastfeeding. Mixed strategies were reported for including human milk into KDT. The two most reported practices were (1) calculating the amount of expressed human milk and bottle-feeding it along with ketogenic formula, and (2) bottle-feeding ketogenic formula followed by breastfeeding. The percentage of human milk contained in KDT varied widely and was usually unmeasured or customized on an individual basis by most respondents. Table 5 shows the different strategies of using human milk.

| Method | Respondents |

|---|---|

| Calculated amount of expressed human milk mixed with KDT formula at every meal | 23 |

| Calculated amount of KDT formula (standard solution) followed by breastfeeding | 22 |

| Calculated amount of KDT formula (standard solution) after breastfeeding | 3 |

- Abbreviation: KDT, ketogenic diet therapy.

Calculated amount of expressed human milk at every meal

The calculated volume of expressed human milk per day was 5% to 10% (n = 5), 10% to 25% (n = 8), 30% to 50% (n = 3), or was calculated individually (n = 6).

Calculated amount of KDT formula followed by breastfeeding

The estimations of the volume of human milk consumed varied greatly among respondents. One-third had the volume measured on the basis of individual circumstances (n = 10), or by time spent at the breast and measured post-meal ketosis (n = 8), while another third did not measure volume at all (n = 9) or did not apply any of the suggested measurements (n = 8). Some respondents weighed the infant before and after breastfeeding (n = 4) and allowed one or two separate full breastfeeds per day alongside bottles of ketogenic formula (n = 1).

Some respondents reported that allowing breastfeeding was motivated by adequate levels of ketosis, infants' ages, mothers' preferences and abilities, and by the individual's level of seizure control (e.g. if seizure control was good without measuring human milk, no additional steps appeared necessary; however, in case of poor ketosis or seizure control, accuracy needed improvement). Most often, the first ketogenic meal was started with a ketogenic bottle, and then breastfeeding was allowed overnight, albeit with limited feeding time.

However, other respondents did not use breastfeeding inclusion strategies, because most preferred expressed human milk mixed with ketogenic formula, or only expressed hindmilk, or stopped breastfeeding altogether when infants started KDT.

The second survey (n = 28, 2023) showed that current practice is on average the same as in 2021: calculated expressed milk mixed with KDT formula (n = 18), calculated amount of KDT formula followed by breastfeeding (n = 6), and eight centres did not respond.

Summary

In the literature, the strategy of bottle-feeding ketogenic formula at first followed by breastfeeding was undertaken only in six reported cases out of eight where breastfeeding was included;16, 27 all other infants received ketogenic formula mixed with a calculated amount of expressed human milk. According to our survey, both strategies are applied with similar frequency in clinical practice. Strategies to improve accuracy included limiting breastfeeding time and weighing the infant before and after breastfeeding. However, most measured no volume at all, particularly when ketosis was adequate and seizure control good.

The reported range of 5% to 50% daily volume as expressed human milk was consistent with the results of our survey, as half of the respondents (n = 13) were using 5% to 25% of daily volume as expressed human milk.

Recommendations

The strategy of choice on how to use human milk as part of KDT is dependent on several factors: availability of human milk, mothers' desires to express or breastfeed, the infant's health status, and their ability to be breastfed.

Ideally, ketogenic formula should be given by bottle in the first instance, followed by breastfeeding. With this method, both the infant and the mother would benefit from breastfeeding.

The level of accuracy should depend on the level of seizure control: in case of poor seizure control, feeding problems, or insufficient ketosis, using expressed human milk instead of breastfeeding is recommended.

Monitoring

Adverse events

KDT is associated with the risk of adverse events. As with any KDT, dietary and medical monitoring is required. Gastro-intestinal side effects are the most common, usually transient, and controlled with diet modification without the need to stop KDT. These have been described in the current guidelines;8, 9 however, new studies have emerged. In summary, early adverse effects in infants under 2 years were most commonly hypoglycaemia and vomiting, while after 1 month of KDT metabolic acidosis, vomiting, and constipation were more frequent,66 with acute adverse effects occurring more frequently in infants under 1 year. In the past, a higher risk of lethargy and kidney stones was observed when children were younger,67 and hypercalciuria independently increases the risk of developing kidney stones.68 Up to 7% of children develop kidney stones while on KDT (uric acid, calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, or mixed stones).68, 69 The risk further increased with long-term treatment66, 70 and concomitant use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors owing to metabolic acidosis.71

There is no evidence suggesting that using human milk prevents or aggravates such risks.

Survey

Twenty-six centres targeted a specific level of ketosis, with 18 targeting a ketone range between 2 and 3 mmol/L, eight targeting a ketone level between 3 and 4 mmol/L, and only one centre targeting 4 mmol/L or more. Four centres did not target a specific level of ketosis at all.

Low ketone levels (<1.5 mmol/L) were responsible for the KDT modification in 27 of the respondents, as was high ketosis (>5 mmol/L) in 23. Intermediate illnesses were a reason for 12 to modify the diet.

Recommendations

Clinical examinations and monitoring during KDT should be performed as suggested in the infant guidelines for KDT:8 that is, a dietician and a physician experienced in KDT management should closely monitor and manage the infant.

Challenges of using human milk in KDT in infants

Literature

Reports of challenges while using human milk or breastfeeding during KDT are limited, but maternal discomfort (mother bitten by the infant, pain when expressing human milk) were common reasons why mothers chose to stop using human milk or breastfeeding.27 In the past, mothers were often told to stop breastfeeding before starting KDT with their child,28 thereby depriving the mother of choice.36 However, to date, systematic data on challenges for human milk inclusion and breastfeeding during KDT are lacking.

Survey

Respondents reported that the main challenges of using human milk in KDT were low ketosis (n = 27), high ketosis (n = 23), reduced production of human milk (n = 20), severe clinical condition of the infant (n = 15), food refusal/low fluid intake (n = 14), intercurrent illness (n = 12), frequently low ketosis (n = 10), ineffective suckling (n = 10), inexperienced mother (n = 6), and frequently high ketosis (n = 3).

Summary

Two main issues limited the use of human milk in KDT. First, there were infant-related issues that were relatively common: fluctuations in ketosis, poor infant health, food refusal, and intermittent illness. Second, there were issues related to the mother that are common issues in any mother–infant dyad owing to stress: low milk production, little breastfeeding experience, and ineffective suckling.

Recommendations

Clinical examinations should be performed as suggested in the infant guidelines for KDT.8 Nurses specialized in breastfeeding should provide support and advice on the practical aspects of breastfeeding.

Assessment of response to KDT: seizure- and non-seizure-related outcomes

The infant guidelines recommend that the evaluation period for KDT8, 9 is at least 2 to 3 months and the diet should be continued during this period. Earlier evaluation is necessary though for infantile epileptic spasms syndrome where KDT is recommended as second- or third-line treatment.8, 9, 72 The goal in infantile epileptic spasms syndrome is seizure freedom. An assessment of response to KDT should be evaluated after 4 weeks because psychomotor development is crucial at this age72, 73 and changes in medication may be required alongside KDT.

Non-seizure-related outcomes have to be included which measure improvements in cognition, alertness, attention, and behaviour; these are mostly reported subjectively rather than systematically owing to the lack of standardized cognitive and quality of life outcomes.74, 75

Literature on human milk in KDT and assessment of response

Effectiveness of KDT treatment on seizures in infants using KDT with human milk is described in detail in the literature review (Table 1),16, 27-29 and ranged from 33% to 53% for seizure freedom, and from 67% to 80% for a reduction in seizures of more than 50%. This is consistent with the effectiveness reported in the literature in this age group without using human milk, where a seizure reduction of more than 50% occurs in an average of 60% of infants, and seizure freedom in about 30%.2, 4, 6, 7, 11

Non-seizure-related outcomes were only reported in the study by Le Pichon et al.,29 which showed an improvement in quality of life in 89% of infants using a parental report with yes/no questions on alertness, interactions, and performance in school.

Survey

The main reported outcome measures were seizure reduction (n = 27), improvement of motor symptoms/dystonia in GLUT1 deficiency (n = 26), seizure freedom (n = 21), and others (n = 5); improved well-being, improved development, attention and perception, improving intestinal flora, and not specified.

Recommendations

Seizure-related outcomes remain the focus for outcome assessment in KDT. A core outcome set of domains for KDT in childhood epilepsy including non-seizure-related outcomes was recently developed by consensus involving parents and health-care professionals.72 Further development of this work will enable its implementation both in research and in clinical settings to standardize non-seizure-related outcome measures, although this is difficult for infants in the first year of life.

REASONS FOR DISCONTINUATION

Reasons for discontinuing human milk use in KDT

Literature

Reports in the literature on reasons for discontinuing human milk/breastfeeding are limited. Factors related to the infant were increased lactate,27 increasing age,28, 29 and decreased interest.29 Maternal factors included discomfort27 and loss of milk production.29

Survey

The most important reasons for discontinuing human milk in KDT were shortage of human milk (n = 22), inadequate ketosis (n = 14), and severely compromised infant health (n = 13). Other reasons reported were severe adverse events (n = 6) and maternal inexperience of breastfeeding (n = 4).

Reasons for discontinuing KDT

The infant guidelines8 addressed this issue and suggested trying to discontinue KDT once children have been monitored for at least 2 years. However, given the typical age-related nature of infantile epileptic spasms syndrome, one randomized controlled trial has reported a shorter use in this syndrome.76 Conversely, those with GLUT1 and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiencies benefit from continuing KDT, in some form, indefinitely. No recent data support changing this recommendation.

Recommendations

Apart from difficulties maintaining breastfeeding or obtaining expressed human milk, discontinuation of KDT should follow previously published recommendations.

The mother's desire to use human milk should be at the heart of the decision to continue or discontinue breastfeeding. In case of human milk shortage, consider using milk from a human donor.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The use of human milk and breastfeeding in KDT for infants and newborn babies is limited in daily practice, which has not changed in recent years. By reviewing the literature and using data about current practice collected by two international surveys (2021 and 2023), we present our collective advice about the inclusion of human milk in KDT in Table 6.

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Human milk can be implemented in KDT which does not change indications or contraindications of KDT in infants. |

| 2 | Ideally, ketogenic formula should be given by bottle first, followed by breastfeeding. With this method, both the infant and the mother would benefit from breastfeeding. |

| 3 | Use expressed milk in case of poor seizure control, insufficient ketosis, poor growth, and feeding difficulties. |

| 4 | The amount of expressed milk ranges from 5% to 50% depending on ketosis and seizure control. Mothers should be stimulated to continue pumping and store expressed milk for maintenance of KDT. |

| 5 | In theory, hindmilk would be preferred. |

| 6 | Use standardized values of human milk for diet calculation. |

| 7 | Nutritional composition of the KDT is calculated according to recommendations from infant guidelines. |

| 8 | Moderate KDT ratio ranging from 2.0:1 to 2.5:1 for adequate protein intake. |

| 9 | Analyse human milk composition when there is insufficient ketosis, seizure reduction, or growth issues. |

| 10 | Maternal diet may only be adapted by an expert team while monitored closely and in case of poor seizure control in a breastfed child. |

| 11 | Ketone levels, monitoring, evaluation of effectiveness, and discontinuation according to the 2016 infant guidelines. |

| 12 | Consult a lactation nurse to support mothers. |

- Abbreviation: KDT, ketogenic diet therapy.

Barriers to the inclusion of human milk and breastfeeding in KDT have only been partly overcome in KDT compared with phenylketonuria or other inborn errors of metabolism. In clinical practice there is a lack of referrals and therefore opportunities to implement this approach, especially in newborn babies. Even experienced KDT practitioners often prefer to include expressed human milk instead of including breastfeeding, to accurately calculate the dietary components. As the surveys have shown, there are many ways to include human milk in KDT. It remains unclear whether the way human milk is included in KDT results in any change in the effectiveness on seizure reduction, time to reach ketosis, or occurrence of adverse events. The inclusion of lactation consultants could increase the success of including human milk and breastfeeding in the feeding regimens of infants on KDT. A supplemental nursing system is a tool that could be used to simultaneously provide both human milk and ketogenic formula to an infant while breastfeeding. A small tube next to the mammilla delivers formula as the infant sucks, which could allow more precise control of formula volume. With the supplemental nursing system, foremilk can be discarded or medium-chain triglycerides can be used instead of KDT formula for infants with intolerance and is certainly worthy of further exploration.77

However, there is also a need to encourage and further investigate not only the use of human milk during KDT but also breastfeeding with all its physiological benefits. Increased knowledge of the nutritional aspects of human milk, either through analysis of human milk or by using specific parts of human milk (hindmilk), can help to develop more precise strategies for the inclusion of human milk and breastfeeding during KDT. The use of human milk does not change either knowledge or previously published guidelines for the use of KDT in infants but rather complements them for the benefit of mother and child.

Non-seizure-related outcomes that have not been systematically studied in KDT so far need to be implemented in future research, and specifically tailored to infants. Prospective real-world registries would be the ideal way to gather further information and guide practice in terms of KDT at all ages.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all centres that have contributed by responding to the questionnaires. We also thank Stéphanie Voogd for her testimonial (Appendix S3), and Anika Maass and Francesca Sutter for reviewing the pocket guide. A pocket guide for clinicians was developed and design was supported by Nutricia (Appendix S4).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have stated that they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

There is no data available.