How commonly do children with complex cerebral arteriopathy have renovascular disease?

Abstract

Aim

To describe the frequency of renovascular abnormalities and hypertension in an opportunistic cohort of children with complex cerebrovascular disease from a single tertiary/quaternary referral centre.

Method

This was a retrospective case note and imaging review of children who had had cerebral and renal angiography, with a diagnosis of moyamoya or other occlusive cerebrovascular disease (OCVD). Hypertension was defined as at least three systolic blood pressure readings of the 95th centile or above.

Results

Of 34 children (12 males, 22 females; median age 5y 11mo, range 2mo-15y 3mo; 20 with moyamoya, 14 with OCVD), primary presentation was neurological in 29 (arterial ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or headache) and with hypertension in five. Renovascular abnormalities were identified in 17, of whom 10 had main renal artery stenosis. Renovascular involvement was not predictable according to arteriopathy diagnosis. Blood pressure was rarely plotted on centile charts. Using the 50th height centile for blood pressure, and based on a median of five systolic blood pressure readings per patient, 20 out of 34 met the definition for hypertension (15/29 patients with primary neurological presentation).

Interpretation

Renovascular abnormalities were common in this group of children with complex cerebrovascular disease. Blood pressure was frequently abnormal but rarely measured and infrequently plotted on centile charts. Neurologists should be alert to potential systemic vascular involvement and its sequelae in children with complex cerebrovascular disease.

Abstract

This article is commented on by Buerki and Steinlin on pages 297–298 of this issue.

Abbreviations

-

- AIS

-

- Arterial ischaemic stroke

-

- DSA

-

- Digital subtraction angiography

-

- ICA

-

- Internal carotid artery

-

- OCVD

-

- Occlusive cerebrovascular disease

-

- RAS

-

- Renal artery stenosis

What this paper adds

- Renovascular disease is often associated with complex childhood cerebrovascular diseases.

- Hypertension is common in children with moyamoya or OCVD.

- Hypertension may be secondary to cerebral hypoperfusion, and a consequence of renovascular disease.

- Blood pressure should be plotted and renovascular investigations considered in childhood complex cerebrovascular disease.

Arterial ischaemic stroke (AIS) is a devastating childhood disorder, which results in long-term neurological morbidity in two-thirds of survivors.1 Most children have abnormalities, or arteriopathies, of the cerebral or cervical circulation.2 Specific morphologies of arteriopathy, in particular moyamoya (occlusive terminal internal carotid artery [ICA] disease with basal collaterals) are associated with a high recurrence rate for AIS. Not all patients with complex occlusive cerebrovascular disease (OCVD) can be categorized using current arteriopathy definitions;3 however, clinical experience suggests that as well as children with moyamoya, these children with complex cerebrovascular disease have the most severe clinical problems and a high likelihood of having a systemic or genetically mediated arteriopathy.4

In children with cerebral arteriopathy hypertension may be secondary to concurrent renovascular disease, but may also reflect a systemic response to cerebral hypoperfusion.5 Conversely, children with renovascular hypertension commonly have concurrent cerebrovascular disease,6 further highlighting the potential multisystem nature of vascular disease in young patients. Management of hypertension in these patients is complex as reduction in systemic blood pressure could lead to critical cerebral ischaemia if the cerebral circulation is ‘pressure passive’ (i.e. cerebral perfusion pressure is directly dependent on systemic blood pressure);5 on the other hand, the end effects of chronic hypertension include cerebrovascular disease and stroke.7

There are few data on the frequency of renovascular involvement in childhood moyamoya or other OCVD. Two studies of Japanese patients with moyamoya reported renovascular disease in 11 out of 159 assessed (five children). There was main renal artery stenosis (RAS) in 5% in one study8 and 7% in the other.9 The data on renovascular involvement in non-East Asian childhood moyamoya are limited to five cases, so it is difficult to estimate its frequency.10, 11 There are clear clinical and genetic differences between East Asian (Japanese/Korean) patients with moyamoya and those of other ethnicities and it is possible that the two groups also differ in terms of frequency of extracerebral involvement.12 Patients with complex OCVD are poorly described in the literature; however, such complex disease morphology is often seen in the context of Mendelian disorders, suggesting that this is potentially a hallmark of genetic or multisystem disease.4 Here we describe the frequency of renovascular abnormalities and hypertension in an opportunistically identified group of children with moyamoya and other complex OCVD.

Method

This was a retrospective review of children seen at Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, between 1994 and 2011 who had undergone both renal and cerebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Selection of patients for cerebral DSA was at the discretion of the treating clinician; based on our practice in this tertiary/quaternary centre, such patients usually either present to the neurology service with AIS (acute focal neurological event with infarction in an arterial territory region), transient ischaemic attacks (acute focal neurological event with resolving symptoms), or headache, or to the renal unit with drug-resistant hypertension. Our practice in the neurology unit is initially to evaluate patients with non-invasive imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We undertake cerebral DSA in children with moyamoya, for confirmation of diagnosis and pre-surgical evaluation, or in those with complex OCVD (defined as stenosis or occlusion of more than one cerebral or cervical artery, not meeting the diagnostic criteria for moyamoya) for diagnosis and identification of treatment targets (e.g. stenting/angioplasty/bypass). Since 2007 renal DSA has also been performed routinely in children having cerebral DSA for these indications. This was less consistent before 2007. Cerebral DSA is also performed in certain children undergoing renal DSA for evaluation of drug-resistant hypertension. Our indications for performing renal DSA in children with hypertension include neurological symptoms (headache or focal neurological deficits), other clinical evidence of multi-system arterial disease, a syndrome predisposing to renovascular disease (such as neurofibromatosis type 1), clinical signs (such as a renal bruit), findings on non-invasive imaging (such as abnormal renal artery Doppler studies), or poor blood pressure control on two or more antihypertensive medications. All patients undergo a standardized clinical, laboratory, and radiological evaluation for primary and secondary systemic/central nervous system vasculitides (including blood and cerebrospinal fluid examination for inflammatory markers, autoantibodies, and evidence of end-organ involvement, e.g. echocardiogram, fundoscopy); those with a final diagnosis of vasculitis were excluded from the current patient group.13

The following data were extracted from the medical records: age, sex, date, and nature of presentation; they were divided into primarily neurological (AIS/transient ischaemic attacks/headache as first symptom) or non-neurological (with hypertension as first indication) and concurrent diagnoses. The five children who initially presented with hypertension went on to have neurological symptoms (AIS in three and transient ischaemic attacks in two).

Digital subtraction angiography had been performed by one or more of a team of several paediatric interventional radiologists and interventional neuroradiologists, under general anaesthesia. Selective angiography of ICAs, external carotid arteries, vertebral arteries, and renal arteries was performed at the discretion of the operator. Cerebral angiogram results were used to categorize cerebrovascular disease as moyamoya (using the definition in Fukui and Natori et al.: essentially bilateral occlusive disease of the terminal ICA/proximal middle cerebral arteries with basal collaterals)14, 15 or OCVD (defined above). Other angiographic features recorded included whether cerebrovascular disease was unilateral or bilateral, and whether there was posterior circulation involvement. Patients with both moyamoya disease (idiopathic) and moyamoya syndrome (associated with another condition) were included in the group with moyamoya. Brain MRI reports were used to identify the presence of cerebral infarction.

Renal DSA images (available for 31/34 patients) were reviewed by one of the authors (DR) to identify abnormalities in main, branch, or peripheral arteries. For these purposes, the following definitions were used. The main renal artery (sometimes multiple) is the segment that arises from the aorta, until its first branching point (excluding non-renal branches). The branch renal arteries are the segments between the main renal artery as far as, and including, the interlobar arteries. The peripheral renal arteries, including the arcuate arteries (at the corticomedullary interface) and interlobular arteries (which lie in the renal cortex), are at the limit of the resolution of DSA. Where original imaging was not available, the results of the clinical radiology report were included in the analysis. We focused on abnormalities of the main renal artery as the clinical relevance of these is clear and they are amenable to interventional therapy. Although abnormalities of more peripheral renal vasculature were noted, their clinical significance was less certain.

Data on blood pressure were obtained from chart review. As height was inconsistently documented in the case notes, the 50th centile for the child's age was used to plot blood pressure on age- and height-related centile charts. Hypertension was defined as at least three systolic blood pressure readings of the 95th centile or above for age and height.16 Approval for this study was deemed not to be required by the ethics committee of our institution.

Results

Thirty-four children (12 males, 22 females; median age 5y 11mo, range 2mo-15y 3mo) were included; their details are summarized in Table 1. Twenty out of 74 (27%) patients with moyamoya seen during this period who underwent cerebral angiography also had renal DSA. The 14 children categorized as having OCVD had a range of occlusive abnormalities (stenosis/occlusion) in the cervical and/or intracranial cerebral arterial circulation. None were categorizable using current paediatric cerebral arteriopathy definitions.3 Considering these in more detail, five children had diffuse occlusive disease of large, medium, and small intracranial arteries but investigations (including cerebral biopsy in one) that were negative for vasculitis. Three others had long segment stenosis of the cervical ICAs (bilateral in two), without radiological features of arterial dissection. Two children had bilateral terminal ICA stenosis, with proximal ICA ectasia in one (who was heterozygous for ACTA2 R179H), but without basal collaterals, thus not fulfilling the criteria for moyamoya. A further two had occlusive disease of one ICA and of the posterior circulation (vertebral artery in one and posterior cerebral artery in the other). The final two had occlusion of the intracranial terminal ICA on one side and a focal stenosis of the cervical ICA on the contralateral side.

| Moyamoya (n=20) | OCVD (n=14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Male/Female | 6/14 | 6/8 |

| Age: median (range) | 6y (9mo–15y 3mo) | 5y 1mo (2mo–13y 4mo) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 15 | 11 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 |

| Black | 4 | 1 |

| Primary clinical presentation | ||

| Neurological (transient ischaemic attacks/AIS/headache) | 19 | 10 |

| Non-neurological: hypertension | 1 | 4 |

| Cerebral imaging | ||

| Infarction presenta | 19 | 13 |

| Posterior circulation (n=33)b | 6/19 | 8/14 |

| Bilateral disease | 20 | 12 |

- a Arterial territory infarction; none of the patients had changes suggestive of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

- b Information on posterior circulation involvement was not available for one patient with moyamoya. OCVD, occlusive cerebrovascular disease; AIS, arterial ischaemic stroke.

Sixteen patients had potentially relevant concurrent diagnoses,2 with more than one diagnosis in two patients: these were three children with neurofibromatosis type 1, two with trisomy 21, one who was heterozygous for factor V Leiden and Factor II 20210A, two heterozygous for ACTA2 R179H, three with cutis marmorata, six with congenital heart defects (two in a single patient), one with haemolytic anaemia, and one with hypothyroidism.

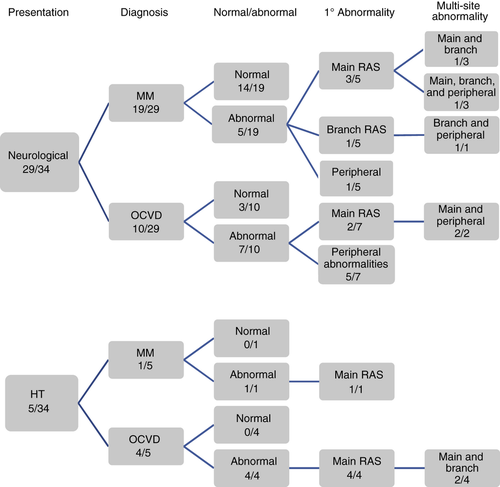

Renal angiograms were available for review for 31 patients (91%); reports were analyzed for the remaining three. The results are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 2. Main RAS was identified in 10 patients. As shown in Table 2, five of these children had had their primary clinical presentation with hypertension; the other five had primary neurological presentations. Two of the five patients presenting with hypertension with main RAS showed additional branch RAS. Five patients with primary neurological presentations also had multi-site renovascular abnormalities (Fig. 1). The frequency of any abnormality was significantly higher in the group with OCVD (11/14) than that with moyamoya (six/20; χ2 test, p=0.014). However, considering main RAS, this was seen in four out of 20 patients with moyamoya and six out of 14 of the OCVD group; this difference was not significant (Fisher's exact test, p=0.25). Of 32 out of 34 reports and/or images where sufficient data were available, abnormalities had been noted in the aorta in six patients (three with moyamoya, three with OCVD), five of whom had bilateral main RAS. Other abdominal arteries (coeliac trunk, iliac arteries, superior mesenteric artery) were involved in three (one with moyamoya, two with OCVD). One patient, with OCVD, had bilateral main RAS, branch and superior mesenteric artery stenoses, and aortic abnormalities, with renal DSA appearances suggestive of fibromuscular dysplasia (although the morphology of the cerebrovascular disease did not meet criteria for diagnosis of cerebral fibromuscular dysplasia). Another patient, diagnosed with OCVD, had a main renal artery aneurysm.

| Diagnosis | Primary clinical presentation (n=34) | Main RAS (bilateral) (n=10) | All abnormalities (n=17) | Hypertension (n=20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moyamoya | Neurological, n=19 | 3 (2) | 5/19 | 10/19 |

| Hypertension, n=1 | 1 (1) | 1/1 | 1/1 | |

| OCVD | Neurological, n=10 | 2 (2) | 7/10 | 5/10 |

| Hypertension, n=4 | 4 (3) | 4/4 | 4/4 |

- RAS, renal artery stenosis; OCVD, occlusive cerebrovascular disease.

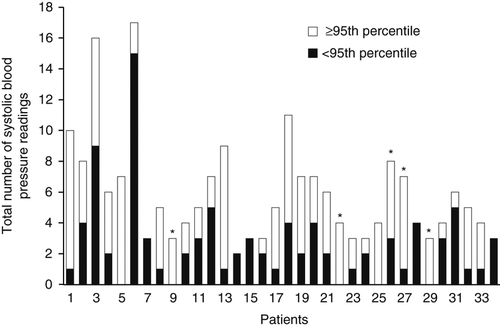

The number of blood pressure readings recorded in case notes per patient was 2 to 17 (median five), over a median period of 1 year 11 months (Fig. 2). Twenty patients met the definition for hypertension (including 15 with a primary neurological presentation, five of whom had main RAS). This association should, however, be interpreted with caution because of concerns about the robustness of the hypertension data. We were unable to comment on the timing of blood pressure measurements in relation to first diagnosis; however, usually the radiological evaluation was undertaken once either neurological symptoms or hypertension were established, in the course of exploring treatment options.

Discussion

Both renovascular abnormalities and hypertension were common in this group of children with complex cerebral arteriopathies, namely moyamoya and other complex uncategorizable OCVD. The rate of main RAS (20%) in our group with moyamoya was greater than the 5 to 7% previously noted in Japan.8, 9 This may be because our group was more heterogeneous, and it highlights the importance of being critical in applying findings from the homogenous Japanese moyamoya cohorts to people of other ethnicity.

Assessment of blood pressure was often suboptimal in the children with primary neurological presentations, with few data on how it was recorded and infrequent plotting on appropriate blood pressure centile charts. Using pragmatic criteria, however, over half the children in this group met the definition for hypertension; we feel this issue merits more systematic study. There are clearly many deficiencies in the data presented here, not least the highly selected group of patients and the inclusion of some children with a primary presentation with hypertension (but who all went on to have neurological events). Nonetheless, although we acknowledge that these data do not allow precise estimation of the frequency of renovascular abnormalities or hypertension in this group, the practical message is that both of these are seen in association with moyamoya and complex OCVD, and should be considered as part of the clinical evaluation of such children. Although the overall frequency of renovascular abnormalities was higher in OCVD than moyamoya, main RAS occurred with a similar frequency in both groups. We would be cautious about over-interpreting statistical analysis in this small group and conclude that our results suggest that renovascular disease is a concern in patients with both morphologies of cerebral arteriopathy.

As understanding of childhood cerebral arteriopathies continues to expand, it is clear that many patients have a systemic, probably genetically determined, aetiology. Moyamoya has a genetic basis in some cases, although this seems to be different in people of differing ethnic backgrounds.4 Recently it has become evident that complex morphologies of cerebral arteriopathy, not at present categorizable using current classifications, are a feature of an underlying genetic disorder. Other syndromic arteriopathies, for example fibromuscular dysplasia, may also be systemic and thus evaluation of children with a cerebrovascular disorder should be comprehensive from this perspective.17, 18

Evaluation of children with cerebrovascular disease should involve detailed clinical examination of the cardiovascular system and echocardiography. AIS and transient ischaemic attacks are generally evaluated using MRI and magnetic resonance angiography in the first instance, which should identify most children with the large vessel cerebral arteriopathies described in the present group. There continues to be an additional yield from cerebral DSA, especially in the evaluation of suspected cerebral vasculitis, a group of patients excluded from the current study. Although it appears reasonable to propose concurrent renal angiography in children having cerebral DSA, basic clinical assessment should include measuring and plotting blood pressure on centile charts. As well as plotting blood pressure according to age and height, other factors that need to be considered are the cuff size, the child's level of cooperation, and the reproducibility of measurements. Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure measurements may be helpful if one-off readings are inconclusive.19 If hypertension is confirmed, children will often first be evaluated using non-invasive tools, such as Doppler ultrasound. Although magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography are reasonably sensitive and specific in the detection of main RAS in children, these techniques are currently inadequate for the exclusion of branch renal artery stenoses, which are common in children. Renal DSA remains the criterion standard and should be pursued if a renal cause is suspected, for example if patients are resistant to pharmacotherapy. The risks of renal DSA are very small, but at a practical level the examination might require coordination between two sets of operators for the cerebral and renal studies respectively. This should be within the remit of a children's hospital.19, 20

The management of hypertension in children with moyamoya and OCVD is contentious as their cerebral circulation is often maximally vasodilated at rest and thus cerebral perfusion pressure is directly related to systemic blood pressure. Even small reductions in blood pressure in such a situation can have catastrophic consequences, and it is critical that this is recognized, especially in periods of intercurrent illness or during anaesthesia. Setting optimal parameters for blood pressure is challenging and in practice many patients will not tolerate ‘normal’ blood pressure from the neurological perspective.5 The management of blood pressure around the time of interventions such as renal angioplasty can be especially challenging as blood pressure may fall abruptly; concurrent medical interventions may need to be withdrawn around the time of such procedures. In patients with moyamoya and hypertension, blood pressure has been reported to fall after surgical revascularization of the cerebral circulation, presumably because of improved cerebral perfusion.21

In conclusion, children with complex cerebral arteriopathies may have an underlying systemic disorder, which may involve the renal vasculature. Measuring and plotting blood pressure should not be neglected and, as has already been well established, patients with hypertension, especially those who are drug-resistant, should be evaluated for RAS.19 Patients undergoing catheter cerebral angiography for evaluation of such cerebrovascular disease should also undergo concurrent angiography of the renal vasculature.

Acknowledgements

AW was supported by a summer vacation studentship from the Child Health Research Appeal Trust. VG is funded by Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity.