Short educational video to improve the accuracy of colorectal polyp size estimation: Multicenter prospective study

Abstract

Background and Aim

Accurate polyp size estimation is necessary for appropriate management of colorectal polyps. Polyp size is often determined by subjective visual estimation in clinical situations; however, it is inaccurate, especially for beginner endoscopists. We aimed to clarify the usefulness of our short training video, available on the Internet, for accurate polyp size estimation.

Methods

We conducted a multicenter prospective controlled study in Japan. After completing a pretest composed of near and far images of 30 polyps, participants received the educational video lecture (<10 min long). The educational content included the knowledge of strategies based on polyp size and criteria for size estimation including the endoscopic equipment size and videos of polyps in vivo. After one month, the participants undertook a posttest. The primary outcome was a change in the accuracy of polyp size visual estimation between the pretest and posttest in beginners.

Results

Participants including 111 beginners, 52 intermediates, and 97 experts from 51 institutions completed both tests. Accuracy of polyp size estimation in the beginners showed a significant increase after the video lecture [54.1% (51.3–57.0%) to 59.0% (56.5–61.5%), P = 0.003]. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the category of beginners and a low score on pretest (P = 0.020 and <0.001, respectively) were the factors that contributed to an increase of ≥10% in the accuracy.

Conclusion

Our educational video led to an improvement in polyp size estimation in beginners. Furthermore, this video may be useful for non-beginners with insufficient polyp size estimation accuracy.

Introduction

Polyp size is used in many guidelines to propose postpolypectomy surveillance interval, as well as polyp number and histology.1, 2 In addition, the recommended endoscopic resection procedures for colorectal tumors have been shown, according to the polyp size.3 Inaccurate polyp size assessment results in the recommendation of incorrect surveillance intervals and treatment methods, which may increase the risk of colorectal cancer or lead to an unnecessary invasive treatment.

Some studies showed that endoscopists often overestimated or underestimated the polyp size.4-6 Our research using the Japan Endoscopy Database also showed that endoscopists tended to prefer specific numbers as the estimated polyp size.7 Although several tools, including biopsy forceps, have been suggested to help endoscopists estimate the polyp size accurately, this additional step requires more time and effort. Moreover, even the polyp size estimated by such tools is not always accurate.8-11 Most endoscopists prefer to rely on subjective visual estimates for determination of polyp size in clinical practice.

It has been shown that beginner endoscopists are less accurate in the visual estimation of polyp size than expert endoscopists.12, 13 As even the size estimation by experts who educate beginners is inaccurate,4-6, 14 an educational tool that allows accurate visual estimation of polyp size without relying on endoscopic equipment is required. A prospective study showed that a lecture involving videos was a useful strategy in improving the accuracy of size estimation without using tools.12 However, this study was performed at a single center with few participants. To improve the quality of colonoscopy, it is important to further educate endoscopists who have insufficient accuracy of size estimation, including beginners. The training modules on polyp size for the endoscopists need to be in a simple and easily accessible form.

We have developed a short video for polyp size estimation, which is available on the Internet. The primary aim of our study was to clarify whether the accuracy of visual estimation of polyp size in beginners can be improved using our video in a multicenter trial.

Methods

This study was a multicenter prospective controlled study. Gastrointestinal endoscopists from all over Japan were recruited between January and March 2019. All endoscopists who provided consent to participate in our study were included. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) withdrawal of the consent; (ii) delay in answering the test questions; (iii) having an unresolved network problem when answering the test questions and watching the educational video. All participants were divided into three categories: beginners, intermediates, and experts. Beginners were defined as endoscopists with <3 years of experience with endoscopic procedures or <300 colonoscopic procedures. Experts were endoscopists accredited by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES). The remaining endoscopists were categorized as intermediates. The study was conducted online. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the pretest. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan (Approval number: C1418). The study was registered in a clinical trial registry (UMIN 000034447).

Pretest and posttest

Our study included a pretest, an intervention (an educational video clip), and a posttest. Diagnostic tests of 30 randomly arranged cases were prepared. An example of polyp case images in the tests is shown in Figure 1. Each case counted for 1 point in the tests. A pair of still images consisting of one close image and one distant image for each case were prepared between December 2018 and February 2019 in Sano Hospital, Hyogo, Japan; no participants were recruited from this hospital in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients regarding the use of their endoscopic images. Colonoscopes (CF-H260AZI, CF-HQ290I, PCF-Q260AI, PCF-Q260AZI, PCF-H290ZI) with LUCERA video processors (Olympus Medical Systems Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) were used. Although it may be more difficult to estimate the polyp size using only two still images than in vivo, it is clinically unusual to estimate only the size of the polyps using motion images. Endoscopists spend limited time in estimating the polyp size. Our study setting is similar to the retrospective estimation of polyp size from still images of patients taken in a clinical situation. The actual polyp size was measured using a flexible measuring probe [Measure (flexed type); Olympus Medical Systems Corporation] in vivo by four endoscopists at Sano Hospital, who were accredited by JGES. The polyp images obtained using the measuring probe were also used to confirm the accuracy of estimation. We allowed an error of ±1 mm in the correct size estimations. Although the size assessment using a measuring probe is reported to be more accurate than that using biopsy forceps, it has been pointed out that the mean difference in the estimated and actual polyp sizes was 3.4%.11 The endoscopic equipment including a linear measuring probe and biopsy forceps cannot always be aligned along the maximum diameter, especially if polyps are situated on acute bends or mucosal folds of the colon. Moreover, few polyp sizes actually take an integer value. It is important to eliminate large outliers from the actual polyp size. Polyps >10 mm were excluded from the test because it was difficult to measure them accurately in vivo using an endoscopic tool. Table 1 shows the distribution of polyps used in the test, which was not revealed to the participants. A username and password were assigned to participants to access the designated website for the test. They were asked to input an integer value as the estimated polyp size on the website. Participants were not able to return to a case once they had answered it. All participants took the posttest one month after the distribution of the educational video. The order of questions in the posttest were re-arranged randomly from those of the pretest. The correct answers for the tests were not disclosed to the participants until this study had been completed.

| Total polyps, n | 30 |

| Mean size, mm (standard deviation) | 5.8 ± 2.5 |

|

Category of size, n Diminutive/small/large |

15/12/3 |

| Size, n | |

| 2 mm | 3 |

| 3 mm | 4 |

| 4 mm | 4 |

| 5 mm | 4 |

| 6 mm | 3 |

| 7 mm | 3 |

| 8 mm | 3 |

| 9 mm | 3 |

| 10 mm | 3 |

|

Shape, n Pedunculated/sessile/flat |

1/12/17 |

|

Histopathology, n Nonneoplastic/neoplastic |

6/24 |

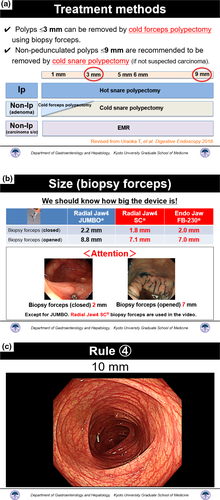

The educational video

After all participants had taken the pretest, we provided them with the link for the educational video. The educational video contents are shown in Figure 2 and Video S1. This video lecture in Japanese was <10 min long and was divided into two parts. The first part included the description of management strategies based on the polyp size, to make the participants understand the need for accurate polyp size estimation. The second part included the description of tips and guides for size estimation including the size of biopsy forceps and snare, and videos of polyp size estimations with and without biopsy forceps in vivo. The presented polyp size in the video was measured using a linear probe. All participants were asked to watch the video at least once.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the change in accuracy from pretest to posttest in beginners. Secondary outcome measures were: changes in accuracy rate from pretest to posttest in intermediates, experts, and all endoscopists; the analysis of factors that contributed to the changes in accuracy rate; and changes in agreement rate of categories between the actual polyp size and the size stated by the participants, when the polyp size was categorized into ≤3, 4–9, and ≥10 mm based on the recommended treatment methods. In addition, changes in the accuracy rate for beginners among size categories of diminutive (1–5 mm), small (6–9 mm), and large (≥10 mm) polyps were also analyzed.

Statistical analysis

As no data on the accuracy of polyp size were available in our study setting and there were no expected disadvantages to the participants, we invited as many participants as possible without setting a sample size. Accuracies for the pretest and posttest were compared using paired t tests. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the agreement rate of categories between the actual polyp size and the answered size. The range of confidence intervals was calculated based on the results of each participant. The multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors that contributed to an increase of ≥10% in the accuracy was conducted based on classification of endoscopists (non-beginners or beginners), sex (male or female), total number of endoscopies conducted, number of endoscopies conducted in the last year, pretest score (30 points at maximum), and number of views of the educational video.15 In the logistic regression analysis, regression coefficients (β) were also calculated to facilitate comparison of each factor. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

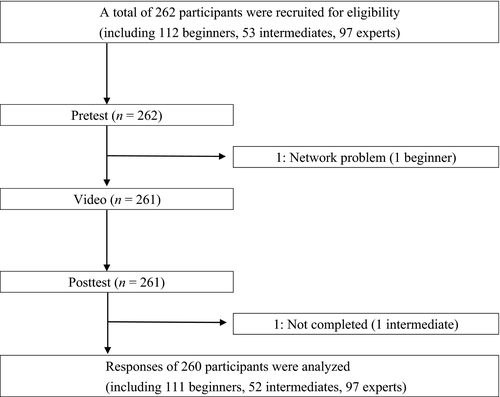

Among 262 enrolled endoscopists from 51 institutions, one beginner did not complete the pretest owing to a network problem, and one intermediate missed the deadline of the posttest (Fig. 3). The participants did not face any trouble in viewing the educational video on the Internet. In this study, 111 beginners, 52 intermediates, and 97 experts from 51 institutions including 11 academic medical centers were included. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the beginners, intermediates, and experts. There were no missing values in the results of tests.

|

Beginner group† (n = 111) |

Intermediate group† (n = 52) |

Expert group† (n = 97) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n | |||

| Male/Female | 85/26 | 43/9 | 82/15 |

| Months of endoscopy experience, mean ± SD, n | 22.8 ± 14.4 | 70.8 ± 38.4 | 147.6 ± 64.8 |

| Total number of endoscopies conducted, mean ± SD, n | 335 ± 376 | 1660 ± 1435 | 3595 ± 3903 |

| Number of endoscopies conducted in the last year, mean ± SD, n | 185 ± 168 | 272 ± 145 | 268 ± 153 |

| Number of views of e-learning video, mean ± SD, n | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.7 |

| Number of participants with a high improvement (≥10%) in accuracy, n (%) | 36 (32.4) | 21 (40.4) | 31 (32.0) |

- SD, standard deviation.

- † Beginner group included endoscopists with <3 years of experience with endoscopic procedures or <300 colonoscopic procedures. Expert group was defined as a group of endoscopists accredited by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. The remaining endoscopists were categorized as the intermediate group.

Table 3 presents the change in the accuracy of polyp size estimation between the pretest and posttest in each group. The mean [95% confidence interval (CI)] scores for the pretest and posttest in the beginners were 54.1% (51.3–57.0%) and 59.0% (56.5–61.5%). The accuracy in the beginners significantly increased after the video lecture. (P = 0.003). There was no significant difference between the pretest and posttest scores in the intermediates [61.7% (57.5–65.9%) to 65.3% (61.8–68.8%), P = 0.167] and experts [62.6% (59.5–65.8%) to 63.8% (61.0–66.7%), P = 0.538], although the test score in all endoscopists also showed a significant increase [58.8% (56.9–60.8%) to 62.1% (60.4–63.7%), P = 0.004].

| Pretest accuracy (95% CI) | Posttest accuracy (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginner group (n = 111) | 54.1% (51.3–57.0%) | 59.0% (56.5–61.5%) | 0.003 |

| Intermediate group (n = 52) | 61.7% (57.5–65.9%) | 65.3% (61.8–68.8%) | 0.167 |

| Expert group (n = 97) | 62.6% (59.5–65.8%) | 63.8% (61.0–66.7%) | 0.538 |

| All (n = 260) | 58.8% (56.9–60.8%) | 62.1% (60.4–63.7%) | 0.004 |

- CI, confidence interval.

Table 4 presents the multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors that contributed to an increase of ≥10% in the accuracy. Eighty-eight participants, including 36 beginners and 52 non-beginners, improved their scores by ≥10% from the pretest. The analysis showed that beginners and lower pretest score was significantly associated with an increase in accuracy. The factor of three points lower pretest score had a higher absolute value of β than the classification of endoscopists (β = −1.131 and −0.973, respectively). Thus, it appeared that a lower pretest score had a stronger influence on the accuracy than the classification of endoscopists. For 71 participants, including 31 non-beginners, with a pretest score ≤50%, the accuracy of polyp size estimation increased from 38.6% (35.9–41.4%) to 57.3% (53.8–60.9%) (P < 0.001).

| Variable | β | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification of endoscopists | Non-beginners | –0.973 | 0.378 (0.166–0.859) | 0.020 |

| Beginners | Reference | Reference | ||

| Sex | Male | –0.277 | 0.758 (0.334–1.720) | 0.507 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Total number of endoscopies conducted | 0.000 | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.547 | |

| Number of endoscopies conducted in the last year | 0.000 | 1.000 (0.998–1.002) | 0.952 | |

| Pretest score | –0.377 | 0.686 (0.620–0.759) | <0.001 | |

| Number of views of the educational video | –0.070 | 0.932 (0.566–1.534) | 0.782 | |

- β, regression coefficient, CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Table 5 shows changes in the agreement rate of categories (≤3, 4–9, and ≥10 mm) between the actual polyp size and the answered size in each group. The rates for the beginners [64.2% (62.1%–66.3%) to 67.8% (66.1%–69.5%), P = 0.006], intermediates [67.9% (65.2%–70.7%) to 72.6% (70.4%–74.8%), P = 0.002], and all endoscopists [66.6% (65.3%–67.9%) to 69.8% (68.8%–70.8%), P < 0.001] were significantly increased after watching the video.

| Pretest accuracy (95% CI) | Posttest accuracy (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginner group (n = 111) | 64.2% (62.1–66.3%) | 67.8% (66.1–69.5%) | 0.006 |

| Intermediate group (n = 52) | 67.9% (65.2–70.7%) | 72.6% (70.4–74.8%) | 0.002 |

| Expert group (n = 97) | 68.6% (66.6–70.6%) | 70.6% (69.1–72.1%) | 0.100 |

| All (n = 260) | 66.6% (65.3–67.9%) | 69.8% (68.8–70.8%) | <0.001 |

- CI, confidence interval.

The changes in the accuracy among size categories of diminutive, small, and large polyps in the beginners are shown in Table 6. Although the accuracy was increased for each size group, only an increase in the accuracy of small polyps was significant (41.5% to 48.1%, P = 0.024).

| Pretest accuracy | Posttest accuracy | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diminutive polyps (n = 15) | 74.5% | 76.6% | 0.448 |

| Small polyps (n = 12) | 34.5% | 41.0% | 0.001 |

| Large polyps (n = 3) | 30.9% | 31.8% | 0.868 |

Discussion

We developed a simple educational video, which is easily accessible on the Internet, to improve the accuracy of colorectal polyp size estimation. Endoscopists should estimate the colonic polyp size accurately to select the appropriate management strategy.1, 2, 16, 17 Our study demonstrated the usefulness of a short educational video for polyp size estimation by beginners in a multicenter prospective trial.

The strengths of our study include participation by a large number of physicians. In particular, there are no previous reports on the accuracy of polyp size estimation among as many beginners as we have reported. In our study, although we allowed a 1-mm error for the assessment of polyp size,18 in the pretest, the average accuracy of size estimation of polyps sized ≤10 mm for beginners was low at 54.1%; it was especially low for small polyps, only 34.5%. This finding would suggest the need to improve the accuracy of size estimation by visual estimation. After viewing our educational video, the accuracy of size estimation for small polyps significantly improved. Inaccurate size-based categorizing of diminutive polyps as small polyps does not lead to insufficient treatment; however, misdiagnosing small and large polyps with regard to size may result in incorrect surveillance intervals and treatment methods.19, 20 Thus, the positive effect on the size estimation of small polyps after our video lecture is clinically important. Moreover, positive changes in the agreement rate of categories (≤3, 4–9, and ≥10 mm) between the actual polyp size and the answered size may also support the beneficial effect of this video on the selection of appropriate treatment methods.

Although the educational video was significantly useful in the beginner group, it did not show any advantages in the intermediate and expert groups. However, the multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that factors significantly associated with a high improvement (≥10%) of accuracy after the educational video lecture included a lower score in the pretest as well as the category of beginners. Some studies showed interphysician variability in experts for the estimation of polyp size.13, 21 Although we initially assumed beginners as a group with a low score in the pretest, experienced endoscopists can also make inaccurate measurements when estimating polyp size. This may indicate that regardless of experience, there is a category of beginners with regard to polyp size estimation, including intermediates and experts, for which our educational video would be particularly effective.

A previous study at a single center also verified the usefulness of an educational module with video clips of polyp size estimations with and without a flexible measuring probe.12 However, interest in polyp size estimation, which may influence the motivation of the participants to learn, may already be higher in that institution owing to the presence of specialists who may have emphasized on the need for accurate polyp size estimation. In the clinical setting, endoscopists often do not pay attention to polyp size estimation because most endoscopists do not have the opportunity to confirm the accuracy of their own estimation. We expected that it was important to increase the participants' interest in polyp size, and thus in the educational video, the need for accurate estimation of polyp size was also described. We developed an educational video that can be easily accessed and viewed in a short time (<10 min) so that endoscopists tried to participate in this trial. Although this educational system involved simple passive learning via a video lecture, it showed an improvement in polyp size estimation in a large-scale study.

This study had some limitations. First, our study was not designed as a randomized controlled trial. The content of the educational video that we provided was simple; therefore, participants in the same institution could share the content with each other easily. This situation is not appropriate for a randomized controlled trial, and to address this issue, a larger number of facilities (with and without the video lecture) will be needed. Second, although the beginner group showed improvement in the test score, the increase in the accuracy was only 4.9%. However, the improvement in accuracy for participants with low pretest scores was remarkable. This effect on the participants with low scores would largely contribute to the standardization of the quality of colonoscopy. An easy strategy of using a short video could help reduce the number of patients who receive inappropriate polyp management owing to a misdiagnosis of the polyp size. In the future, it will be necessary to determine methods to identify the group with inaccurate size estimation that should receive education. The third limitation was the absence of polyps >10 mm in the test because of difficulty in their accurate size estimation using a flexible measuring probe. Further investigation using large polyps is needed. However, we believe that accurate estimation for polyps ≤10 mm would lead to an improvement in the estimation accuracy for polyps >10 mm. Finally, we did not examine how long the educational effect lasts; further studies are needed to address this. However, this video can be used easily to re-educate endoscopists because of its convenience.

In conclusion, our educational video increased the accuracy of visual polyp size estimation in beginners. Furthermore, this video has the potential to be useful to all endoscopists with insufficient accuracy of polyp size estimation, including non-beginners. Although some adjustments in the recommended strategies and size of the endoscopic equipment used in each institution may be needed, we hope that this web-based video for polyp size education will be widely used worldwide.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Shinwa Tanaka, Dr. Nobuaki Ikezawa (Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe University, Japan) and Dr. Masaya Esaki (Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan) for recruiting many participants in this study. We sincerely appreciate all the participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

This research was supported by a research grant from Fujiwara Memorial Foundation and a donation from Merck Biopharma. These organizations played no role in this research.