Endoscopic management of acute cholangitis according to the TG13

Abstract

The Tokyo Guidelines 2013 (TG13) recommend that endoscopic drainage should be the first-choice treatment for biliary decompression in patients with acute cholangitis. Timing of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis should be based on the severity of the disease. For patients with severe acute cholangitis, appropriate organ support and urgent biliary drainage are needed. For patients with moderate acute cholangitis, early biliary drainage is needed. For patients with mild acute cholangitis, biliary drainage is needed when initial treatment such as antimicrobial therapy is ineffective. There are three methods of biliary drainage: endoscopic drainage, percutaneous transhepatic drainage, and surgical drainage. Endoscopic drainage is less invasive than the other two drainage methods. The drainage method (endoscopic nasobiliary drainage and stenting) depends on the endoscopist's preference but endoscopic sphincterotomy should be selected rather than endoscopic papillary balloon dilation from the aspect of procedure-related complications. In the TG13, balloon enteroscopy-assisted and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainages have been newly added as specific drainage methods. Recent studies have demonstrated their usefulness and safety. These drainage methods will become more widespread in the future.

Introduction

Appropriate treatment of acute cholangitis should be based on the severity of the disease. In particular, urgent intervention is mandatory in patients with severe acute cholangitis because the condition can be fatal if untreated. In 2007, the Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis (Tokyo Guidelines 2007 [TG07]) were first published.1 In January 2013, the Guidelines were updated to reflect the needs of clinicians, and its second edition was published as the Tokyo Guidelines 2013 (TG13).2 Using flowcharts, the TG13 provide diagnostic criteria and severity assessment criteria and describe appropriate initial treatment according to severity. Moreover, treatment strategies including antimicrobial therapy, drainage, and surgery are discussed, along with a review of the relevant literature, by refining disease definitions and concepts. Here, we outline endoscopic treatment of acute cholangitis based on the TG13 and current knowledge.

Severity assessment of acute cholangitis

The timing of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis should be based on the severity of the disease. Table 1 shows TG13 severity assessment criteria. Immediately after the diagnosis of acute cholangitis is confirmed, the severity should be determined according to the severity assessment criteria.

| Severe acute cholangitis (Grade III) |

| Patients with severe acute cholangitis have at least one of the following: |

| Cardiovascular dysfunction (requiring dopamine ≥5 μg/kg per min or noradrenaline) |

| Neurological dysfunction (disturbance of consciousness) |

| Respiratory dysfunction (PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300) |

| Renal dysfunction (oliguria or serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL) |

| Hepatic dysfunction (PT-INR >1.5) |

| Blood coagulation disorder (platelet count <100 000/mm3) |

| Moderate acute cholangitis (Grade II) |

| Patients with moderate acute cholangitis have any two of the following at the first examination: |

| Abnormal white blood cell count (>12 000 or <4000/mm3) |

| High fever (≥39°C) |

| Age (≥75 years old) |

| Jaundice (total bilirubin ≥5 mg/dL) |

| Hypoalbuminemia (<STD × 0.73 g/dL) |

| Patients who do not meet the above criteria but do not respond to initial treatment are also classified as ‘moderate’ |

| Mild acute cholangitis (Grade I) |

| Patients with mild acute cholangitis do not meet the criteria for ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ acute cholangitis |

- The table is cited with modification from Reference.3

- PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; STD, lower limit of normal value; TG13, Tokyo Guidelines 2013.

Severe acute cholangitis (Grade III)

Patients with severe acute cholangitis have organ dysfunction and require intensive care such as respiratory and circulatory support. Specifically, the severe acute cholangitis is characterized by the onset of at least one of the following conditions: cardiovascular dysfunction (shock), disturbance of consciousness, respiratory, renal, and hepatic dysfunctions, and blood coagulation disorder. The condition can be fatal unless urgent biliary drainage is carried out.

Moderate acute cholangitis (Grade II)

Patients with moderate acute cholangitis do not have organ dysfunction but have a risk of developing it and, thus, require early biliary drainage. Moderate acute cholangitis is defined as fulfilling any two of the following conditions: abnormal white blood cell count, high fever, older age, severe jaundice, and hypoalbuminemia.

Mild acute cholangitis (Grade I)

Patients with mild acute cholangitis do not meet the criteria for severe or moderate acute cholangitis.

Treatment of acute cholangitis

Treatment of acute cholangitis should be started depending on the severity as early as possible after the severity is confirmed. The TG13 summarize treatment methods for acute cholangitis in a flowchart. For patients with severe acute cholangitis (Grade III), appropriate organ support and urgent biliary drainage are needed. For patients with moderate acute cholangitis (Grade II), early biliary drainage is needed. For patients with mild acute cholangitis (Grade I), biliary drainage is needed when initial treatment such as antimicrobial therapy is ineffective. When patients with severe or moderate acute cholangitis require treatment of the causative disease such as common bile duct stone, it is recommended that biliary drainage only be done as the initial treatment, and treatment of the causative disease be carried out after the patient's general condition has improved.

Selection of biliary drainage methods

There are three methods of biliary drainage: endoscopic drainage, percutaneous transhepatic drainage, and surgical drainage. Endoscopic drainage is less invasive than the other two drainage methods. It is considered the first-line treatment of acute cholangitis irrespective of the benign or malignant nature of the primary disease.4-8 Transhepatic drainage is more frequently associated with accidental complications such as bleeding and peritonitis and, thus, requires longer hospitalization compared to endoscopic drainage. Therefore, this method is currently considered as an alternative to endoscopic drainage.9 Transhepatic drainage is beneficial for patients in whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is difficult to carry out, in those with upper intestinal obstruction, and those in whom endoscopic access is difficult because of previous gastrointestinal surgery such as Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surgical drainage is currently less frequently used because endoscopic drainage is widely used.

Practical use of endoscopic biliary drainage

Indications and timing

Endoscopic transpapillary biliary drainage is a minimally invasive drainage technique. It is the gold standard treatment for acute cholangitis irrespective of the benign or malignant nature of the primary disease. However, this technique may be difficult to carry out for patients with gastric or duodenal obstruction and those after surgery such as Roux-en Y anastomosis.

The timing of endoscopic drainage is crucial for better clinical outcomes. Khashab et al. reported that patients undergoing drainage more than 72 h after admission and those in whom drainage is unsuccessful have poor outcomes.10 Regarding the timing of biliary drainage, Kiriyama et al. reported as follows.11 In a multicenter analysis assessing TG13, of the 623 cases of acute cholangitis, severity grading was made clear, Grade III is 12%, Grade II is 35% and Grade I is 54%. Furthermore, the Grade II or III cases requiring immediately biliary drainage accounted for 46%. Actually, biliary drainage was carried out within 24 h, in Grade III 57%, in Grade II 54%, in Grade I 42%.

Selection of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage or endoscopic biliary stenting

There are two types of endoscopic drainage: endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS). A randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the two methods found that discomfort score on a visual analogue scale (VAS) was higher in the ENBD group than in the EBS group, although there were no significant differences in drainage outcomes including technical success rate, response rate, complication rate, and mortality rate between the two groups.12-14 Therefore, TG13 specify that endoscopists can select either method depending on their preference. When carrying out ENBD for patients with dementia or for elderly patients, continuous attention is needed to avoid self-removal of the tube. In contrast, ENBD, used as an external drainage, has advantages in that direct observation of bile is possible at the bedside and that frequent lavage of the biliary tract is possible when the tube is obstructed with infected, highly viscous bile. In our hospital, ENBD is selected for patients in whom a period of time has passed since the onset of cholangitis and there is evidence of highly viscous bile.

When carrying out EBS, a plastic stent can be selected depending on stent size and type (e.g. straight type and pigtail type). To date, there have been no studies comparing these devices in cholangitis. Accordingly, endoscopists can select a stent depending on their preference.

Should endoscopic sphincterotomy be added?

Unless patients with mild cholangitis as a result of common bile duct stone have blood coagulation disorder, endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) can also be done in an initial stage of operation to remove bile duct stone, thereby leading to reduced length of hospital stay. A RCT has shown that drainage is not required when endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones was done after ES.15 According to the TG13, skilled surgeons can carry out endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones after ES in an initial stage.7 However, the TG07 state that the addition of ES is not necessary because it carries a risk of causing accidental complications such as bleeding,16, 17 and that acute cholangitis, itself, is a risk factor for bleeding after ES.18 Therefore, we consider that ES should be avoided for patients with severe acute cholangitis (Grade III) or coagulation disorder. Such patients should be treated with drainage alone and the initial treatment should be completed in a short time.

Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation

Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD) can be used as an alternative to ES. When carrying out bile duct stone removal, EPBD has advantages in preserving papillary sphincter function and preventing the recurrence of bile duct stones for a long period of time.19, 20 EPBD also has an advantage in reducing postoperative bleeding.21 Although there are no studies comparing EPBD and ES for the treatment of cholangitis as a result of bile duct stones, it is anticipated that addition of EPBD, as well as ES, leads to decreased treatment sessions and reduced hospital stay. A systematic review has shown that EPBD is less successful for stone removal, requires a higher rate of mechanical lithotripsy, and carries a higher risk of acute pancreatitis.21 Therefore, the TG13 conclude that EPBD is preferable for the treatment of patients with coagulation disorder and those with small stones.9

Special endoscopic drainage

In the TG13, balloon enteroscopy-assisted and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainages have been newly added as specific drainage methods. Recent studies have demonstrated their usefulness and safety. These drainage methods will become more widespread in the future.

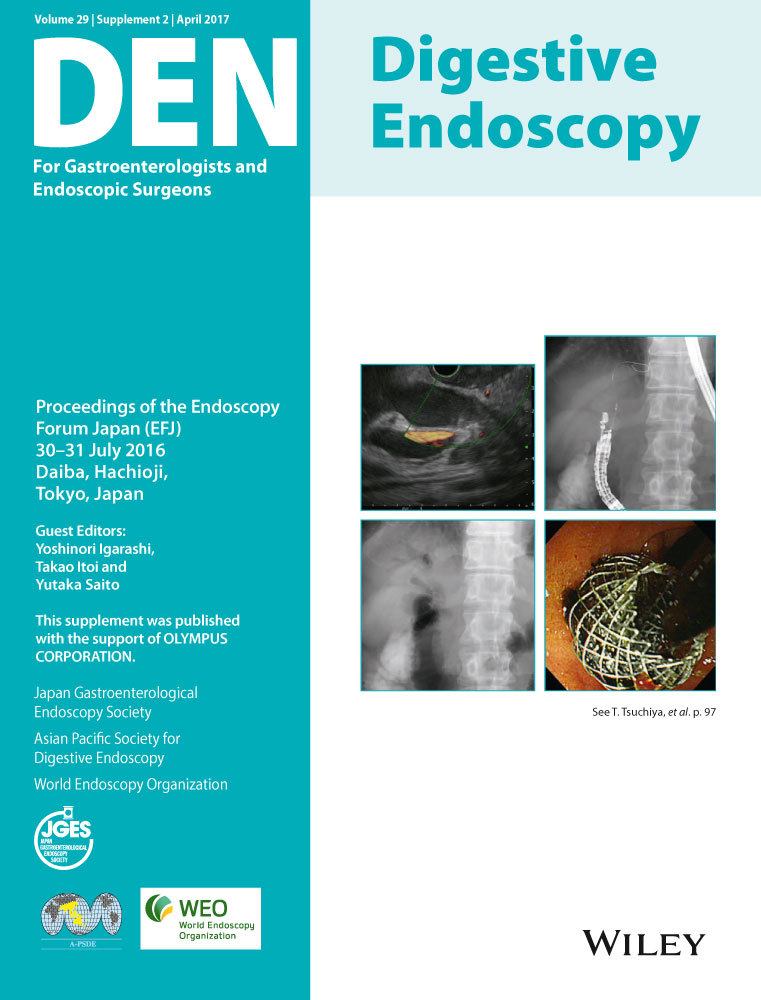

Balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP

ERCP for patients after gastrointestinal surgery is more challenging than usual ERCP with duodenoscopy. In our clinical practice, we encounter patients who underwent choledochojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy or Roux-en-Y reconstruction after gastrectomy. When they have severe adhesion or a long afferent loop, endoscopic access to the papilla or bile duct jejunum anastomosis site is difficult. Recently, single balloon endoscopy (SBE) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) were developed, thereby allowing ERCP to be carried out more readily in such challenging patients. Studies on the utility of DBE in 50 or more patients have shown successful rates of bile duct cannulation to be 74–98%, technical success rates to be 91–100%, and non-serious complication rates to be approximately 5%.22, 23 A systematic review of 15 trials of SBE-assisted ERCP in 461 patients reported that the pooled enteroscopy, diagnostic, and procedural success rates were 80.9%, 69.4%, and 61.7%, respectively, and adverse events occurred in 6.5% of patients.24 The authors concluded that SBE-ERCP has high diagnostic and procedural success rates in this challenging patient population. It should be considered a first-line intervention when biliary access is required after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, hepaticojejunostomy, or Whipple procedure (Fig. 1). Ishii et al. examined 123 ERCP procedures in 109 patients with Roux-en-Y reconstruction after total or subtotal gastrectomy, including 90 patients with intact papilla, and reported favorable results: the overall success rate of reaching the papilla was 93.5% (115/123); the total procedure success rate was 88.1% (96/109); the adverse event rate was 7.3% (8/109); and the final cannulation success rate was 95.6% (86/90).25 Thus, biliary drainage with balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP is a treatment option for patients after gastrointestinal surgery in institutions where endoscopists are skilled in both balloon enteroscopy and ERCP, although this technique is not always successful. So, we must carefully evaluate the patient's condition as to whether the patient can endure endoscopic therapy, and we should prepare for percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) when we select balloon-assisted enteroscopic ERCP in emergency cases.

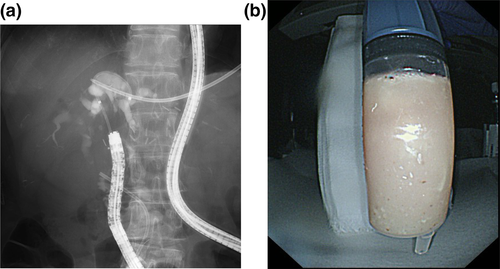

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage

With recent advances in endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) technology, EUS-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) and EUS-guided rendezvous technique have been widely used as salvage therapies for patients in whom transpapillary biliary drainage with ERCP is difficult to carry out.26, 27 In the rendezvous technique, the bile duct is punctuated under EUS guidance, and a guidewire is advanced antegrade through the papilla to carry out transpapillary drainage.28 However, these interventions are not frequently used in clinical practice because they are salvage therapies, used only with patients in whom ERCP is difficult to carry out.29, 30

Currently, PTBD is the standard treatment for patients in whom ERCP is difficult to carry out. Recently, an interesting study examining whether EUS-BD can replace PTBD was conducted (Fig. 2). Lee et al. carried out a multicenter randomized trial to compare EUS-BD versus PTBD for malignant distal biliary obstruction after failed ERCP.31 The resulting rates of primary technical success were 94.1% (32/34) in the EUS-BD group and 96.9% (31/32) in the PTBD group. Rates of functional success were 87.5% (28/32) in the EUS-BD group and 87.1% (27/31) in the PTBD group. Proportions of procedure-related adverse events were 8.8% in the EUS-BD group versus 31.2% in the PTBD group (P = 0.022). Also, they concluded that EUS-BD and PTBD had similar levels of efficacy in patients with unresectable malignant distal biliary obstruction and inaccessible papilla based on rates of technical and functional success and quality of life (QOL).

A systematic review of EUS-BD reported the following results.32 Forty-two studies with 1192 patients were included in this review, and the cumulative technical success rate, functional success rate and adverse-event rate were 94.71%, 91.66%, and 23.32%, respectively. The common adverse events associated with EUS-BD were bleeding (4.03%), bile leakage (4.03%), pneumoperitoneum (3.02%), stent migration (2.68%), cholangitis (2.43%), abdominal pain (1.51%), and peritonitis (1.26%). The authors concluded that there was no significant difference between the transduodenal and transgastric approaches for the technical success rate, functional success rate and adverse-event rate. However, the rate of complications was relatively high although serious complications were not reported. We consider that the procedure is yet to be established and requires specialized skills; therefore, it should be carried out by endoscopists skilled in biliary and pancreatic diseases and who have extensive experience with EUS and ERCP.

Conclusions

Herein, we have outlined endoscopic treatment of acute cholangitis in compliance with the TG13. Acute cholangitis can be life-threatening if not treated adequately and promptly in an acute phase. In particular, accurate diagnosis and treatment is crucial for patients with severe or moderate acute cholangitis who require urgent or early biliary drainage. The development of new useful techniques such as balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP and EUS-BD seem to be promising. Revised TG13 is warranted in the near future.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.