Current status and future perspectives of endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of diminutive colorectal polyps

Abstract

During colonoscopy, small and diminutive colorectal polyps are commonly encountered. It is estimated that at least one adenomatous polyp is detected in almost half of all patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. In contrast, the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy for diminutive and small colorectal polyps is a current topic especially in Western countries. ‘Is this an acceptable policy in Japan?’ Herein, we report the results of a questionnaire survey with regard to the management of diminutive colorectal polyps, including the thoughts of Japanese endoscopists regarding the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy. At the moment, we propose that this strategy should be used by skilled endoscopists only.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most important cause of cancer mortality in Japan.1 In terms of secondary prevention, early detection and endoscopic removal of adenomatous polyps reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.2-4 Therefore, colonic polyps with malignant potential are routinely removed using endoscopic procedures. During colonoscopy, small (6–9 mm) and diminutive (≤5 mm) colorectal polyps are commonly encountered. It is estimated that at least one adenomatous polyp is detected in almost half of all patients undergoing screening colonoscopy.

In contrast, the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy for diminutive and small colorectal polyps is a current strategy especially in Western countries.5-7 Pathological assessment is still considered essential to determine the interval of a patient's next surveillance colonoscopy. This process enables the differentiation of neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions and the identification of advanced histology (high-grade dysplasia or villous components), which require more intensive surveillance. However, even histopathological assessment, which is considered the gold standard for polyp characterization, may have some limitations. Indeed, some authors have reported that the median kappa value for interobserver agreement for the diagnosis of adenomas versus hyperplastic polyps is not perfect (0.89; range 0.79–1.0).8

Recently, magnifying chromoendoscopy has become available as well as other newly developed modalities in daily practice (e.g. narrow-band imaging [NBI], flexible spectral imaging color enhancement [FICE], and autofluorescence imaging [AFI] etc.). These new techniques are more than 90% accurate in the differentiation of adenomas and hyperplastic polyps.9-15 However, such useful modalities have not yet become standardized worldwide. We report keynote lecture presentations from the Endoscopic Forum Japan (EFJ) 2013 in Otaru, Hokkaido, given on 3–4 August 2013. In this part of the program, discussion was held with regard to the treatment strategy of diminutive colorectal polyps <5 mm in size and the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy based on a questionnaire that was completed by all Japanese discussers involved in this conference.

Prevalence of Carcinoma in Diminutive and Small Polyps: Data from five Institutions

A total of 18 705 colorectal lesions treated endoscopically or surgically were collected from five Japanese institutions (National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo; National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa; Tochigi Cancer Center, Tochigi; Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka; Hiroshima University, Hiroshima). To clarify the prevalence of carcinoma in diminutive and small lesions, we classified all lesions into three groups based on lesion size (diminutive: ≤5 mm, small: 6–9 mm and large: ≥10 mm) as shown in Figure 1.

Pathological diagnosis of all polyps. Data are from five institutions with 18 705 lesions treated by endoscopic resection or surgery.

There were 8663 diminutive (46.3%), 5210 small (27.9%) and 4832 large polyps (25.8%). Among all diminutive polyps, there were 35 (0.4%) carcinomas of which four (0.04%) were diagnosed as submucosal (SM) invasive cancers. In contrast, the incidence of intramucosal: (M/SM) carcinoma was 3.0% (2.5%/0.5%) and 25.2% (17.5%/7.7%) in small and large polyps, respectively (Table 1).

| Size | Pathological diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinoma (pM/pSM) | Adenoma | Othersa | |

| ≤5 mm | 35 (31/4) | 7486 | 1142 |

| 0.4% (0.36%/0.04%) | (86.4%) | (13.2%) | |

| 6–9 mm | 156 (131/25) | 4534 | 520 |

| 3.0% (2.5%/0.5%) | (87.0%) | (10.0%) | |

| ≥10 mm | 1216 (846/370) | 3137 | 479 |

| 25.2% (17.5%/7.7%) | (64.9%) | (9.9%) | |

- Total: n = 18 705.

- a Hyperplastic polyp, inflammatory polyp, hamartoma etc.

In general, the prevalence of carcinoma in colorectal polyps ≤5 mm is low; however, the proportion of depressed lesions is significantly higher in carcinomas than in adenomas.16 These data have important implications for the potential use of the ‘predict, resect, and discard strategy’ for diminutive colorectal polyps.

Survey on the Current Status of Endoscopic Management for Colorectal Polyps

This survey was carried out prior to the meeting. The aim of the present survey was to assess the current status of endoscopic management for diminutive/small colorectal polyps in Japan.

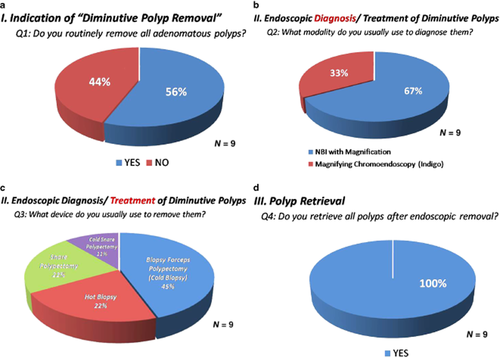

Question 1: Do you routinely remove all adenomatous polyps?

Colonoscopy with adenoma resection has demonstrated that it reduces the risk of subsequent colorectal cancer by as much as 80%2 and is one of the primary screening methods in the USA and in some European countries. However, some Japanese endoscopists leave diminutive adenomatous polyps unresected after detailed observation and close follow up because they consider that many polypectomies are unnecessary and expose patients to added risks during colonoscopy. Fifty-six percent of the Japanese participants responded ‘Yes; remove all adenomatous polyps during screening colonoscopy except in elderly and/or patients with severe comorbidity’ (Fig. 2a). It is considered that the number of colonoscopic examinations in Japan is approximately three million per year. The capacity of endoscopy units is limited; therefore, it is crucial to distribute screening colonoscopies broadly to the unscreened population.

(a) Questionnaire survey report on the indications for diminutive polyp removal. Question 1: Do you routinely remove all adenomatous polyps? (b) Endoscopic diagnosis of diminutive polyps. Question 2: What modality do you usually use to diagnose them? (c) Endoscopic treatment of diminutive polyps. Question 3: What device do you usually use to remove them? (d) Polyp retrieval. Question 4: Do you retrieve all polyps after endoscopic removal? NBI, narrow band imaging.

Question 2: What modality do you use to diagnose diminutive polyps?

Conventional colonoscopy (white-light) has limited accuracy in differentiating neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions. For expert endoscopists, the application of indigocarmine dyes with optical magnification and pit pattern diagnosis enables a very accurate optical diagnosis (85–96%).9-11, 17, 18 In contrast, narrow band imaging (NBI) is a newly developed image-enhanced modality. In previous studies, NBI with magnification has shown a diagnostic accuracy similar to magnifying chromoendoscopy.13, 19, 20 Sixty-seven percent of the participants answered ‘NBI with magnification’ to diagnose diminutive colorectal polyps (Fig. 2b). The major advantages of using NBI are ‘time saving’ and ‘easy to use’.

Question 3: What device do you use to remove diminutive polyps?

Recently, some authors have reported the safety and efficacy of cold polypectomy for removing diminutive/small colorectal polyps.21-23 However, according to a survey of US gastroenterologists, various techniques were chosen to remove small (size: 4–6 mm) colorectal polyps (i.e. 59% of gastroenterologists responded using ‘hot snare’, 21% ‘hot biopsy forceps’, 19% ‘cold biopsy forceps’, and 15% ‘cold snare’.).24 In contrast, 45% (4 out of 9) of the Japanese participants responded using ‘cold biopsy forceps’, 22% ‘hot biopsy forceps’, ‘hot snare’, and 11% ‘cold snare’ (Fig. 2c). In the EFJ 2013 colorectal session, Dr Uraoka introduced jumbo biopsy forceps that have been designed to remove larger tissue samples, as they have a greater capacity for this purpose (Radial Jaw 4 jumbo forceps; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). Some advantages of the jumbo biopsy forceps were reported as having a higher en-bloc resection rate and a lower delayed bleeding rate for diminutive polyps.25

Question 4: Do you retrieve and submit for pathology all resected polyps?

The current practice of removing all diminutive colorectal polyps and submitting them for histopathological assessment has several drawbacks. According to the data of five Japanese institutions (n = 8663, diminutive polyps), the likelihood of having non-neoplastic histology (hyperplastic polyp, inflammatory polyp, hamartoma etc.) was 13.2%, as shown in Table 1. In general, it is considered that approximately 40% of diminutive lesions (≤5 mm) and approximately 25% of small lesions (6–9 mm) are non-neoplastic, mainly hyperplastic, polyps, which is much higher than that seen in the Japanese data. Japanese endoscopists probably diagnose such diminutive/small lesions more accurately using magnifying chromoendoscopy or image-enhanced endoscopy. However, all Japanese participants responded ‘Yes; basically, retrieve all resected polyps and submit them for pathology’ (Fig. 2d). Further analyses on the cost-effectiveness and learning curve of endoscopic diagnosis using newly developed modalities are strongly required. For the moment, the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy should be applied selectively with an accurate inform for further endoscopic evaluations.

Discussion and Conclusion

Recently, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) has developed a Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) program.26 Specific clinical issues addressed by the PIVI are: (i) What accuracy in prediction of histology to determine post-polypectomy surveillance intervals is required for an endoscopic imaging technology to allow colorectal polyps <5 mm in size to be ‘resected and discarded'?; and (ii) What accuracy is required in endoscopic diagnosis to leave rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps <5 mm in size unresected?. Thresholds to satisfy specific clinical issues were the following: (i) the technology should provide >90% agreement in determining post-polypectomy surveillance intervals when compared to pathological assessment of all identified polyps; and (ii) an endoscopic technology should provide >90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology to leave suspected rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps unremoved. The main barrier to applying these results in our clinical practice is the difference between the health-care financial policies in Japan and that in Western countries. As the cost of colonoscopy or pathological assessment is cheaper in Japan, there would be no substantial cost-effectiveness improvement compared to Western countries. Considering the development and widespread use of available new technology, real-time endoscopic diagnosis could be a good alternative for pathological assessment in the near future.

According to the survey at the EFJ 2013 colorectal session, most of the Japanese participants routinely used ‘NBI with magnification’ to diagnose diminutive colorectal polyps and removed them using ‘cold biopsy’ or the ‘cold snare’ technique. Recently, the number of patients who receive oral anticoagulants is increasing. Therefore, we should shift from ‘hot snare/biopsy’ to ‘cold snare/biopsy’ to prevent delayed bleeding. Moreover, the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy is spreading globally; however, all Japanese participants responded that they ‘retrieve all resected polyps and submit them to the pathology department’. In conclusion, we propose that the ‘predict, resect, and discard’ strategy should be used only by endoscopists trained with an appropriate diagnostic method in Japan.

Conflict of Interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.