German-Austrian guideline on screening for anal dysplasia and anal carcinoma in people living with HIV

AWMF Registry No.: 055-007

Guideline valid until: December 31, 2028

Lead Management: Deutsche AIDS-Gesellschaft (DAIG)

Participation of the following scientific societies and working groups:

Österreichische AIDS-Gesellschaft (OEAG)

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Chirurgie (ÖGCH), Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Coloproktologie (ACP)

Arbeitsgemeinschaft dermatologische Onkologie (ADO)

Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft ambulant tätiger Ärztinnen und Ärzte für Infektionskrankheiten und HIV-Medizin (dagnä) e.V.

AIDS Hilfe Wien

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Radioonkologie (DEGRO)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG)

Deutsche dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG)

Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatohistologie (ADH) der deutschen dermatologischen Gesellschaft (DGG)

Arbeitsgemeinschaft Proktologie in der deutschen dermatologischen Gesellschaft (DDG)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und medizinische Onkologie (DGHO)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Koloproktologie (DGK)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Infektiologie (DGI)

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Dermatologie und Venerologie (ÖGDV)

Deutschen Gesellschaft für Zytologie (DGZ)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselerkrankungen (DGVS)

Deutsche STI-Gesellschaft (DSTIG)

Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie (DGAV)

Deutsche Aidshilfe (DAH)

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Sexually Transmitted Diseases und dermatologische Mikrobiologie (OEGSTD)

Gesellschaft für Virologie (GfV)

Summary

People with HIV are up to 100 times more likely to develop anal carcinoma compared to the general population. Diagnosing and treating precursor lesions, specifically high-grade anal dysplasia, can significantly reduce the risk of developing anal carcinoma. This S2k-guideline outlines the factors that increase the likelihood of developing anal carcinoma and its precursors, including advancing age, a low CD4+ T-lymphocyte nadir, active cigarette smoking, receptive anal intercourse, or persistent infection with high-risk (HR) types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Screening is primarily recommended for all men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women with HIV starting at age 35, and all people with HIV starting at age 45.

After inspection and digital anorectal examination, anal cytology is collected. An HR-HPV test may be performed. If clinical abnormalities are present or if cytology shows “ASC-US or worse”, a referral for high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) is indicated. If lesions are found during HRA, a biopsy should be obtained. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) grade-III or AIN-II p16-positive correspond to high-grade dysplasia and require treatment. The most strongly recommended therapeutic options are electrocautery, 85% trichloroacetic acid, and surgical excision.

Finally, the guideline discusses how these screening recommendations can be applied to individuals without HIV.

INTRODUCTION

This document is the concise version of the guideline. The complete version was published online by the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) and is available in German only at https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/055-007. Notably, this is the first update to this guideline since its initial publication in 2015.1 In the revised version, the title has been updated to align with current recommendations for inclusive language. Epidemiological data have also been updated, primarily incorporating the latest analyses of anal carcinoma incidence across various populations. Additionally, new evidence has emerged since the previous version, demonstrating that treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia can reduce the incidence of anal carcinoma. Moreover, we have thoroughly updated the screening recommendations, and the chapter on the treatment of anal carcinoma has been removed, as these topics are covered in a separate S3 guideline on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of anal carcinoma.2 Furthermore, screening for anal carcinoma in individuals without HIV has also been addressed.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Compared to the general population, people living with HIV (PLWH) are more frequently affected by non-AIDS defining cancers like anal carcinoma.3, 4 Anal carcinoma is caused by persistent infections with human papillomaviruses (HPV) in approximately 90%–100% of cases.5, 6 HPV-types are categorized into high-risk (HR) types, which can induce malignant transformation of epithelial cells (notably HPV-16 and HPV-18), and low-risk (LR) types, which are primarily associated with genital warts. Histopathologically, anal carcinomas are typically squamous cell carcinomas.7 Among women with HIV, the prevalence of anal HR-HPV infection is 33% in those who are HR-HPV-negative in the cervix and 62% in those who are HR-HPV-positive in the cervix).8 In men, the prevalence of anal HR-HPV varies depending on HIV status and sexual behavior. A pooled analysis of data from 29,000 men across 64 studies found that anal HR-HPV prevalence increased from 6.9% in HIV-negative men who have sex with women (MSW) to 26.9% in MSW with HIV. Prevalence was even higher in men who have sex with men (MSM), rising to 41.2% in HIV-negative (MSM) and 74.3% in MSM with HIV.9

According to a 2021 meta-analysis, the highest incidence of anal carcinoma occurs in MSM with HIV, with 85 cases per 100,000 person-years (PY). Other groups, such as heterosexual men with HIV and women with HIV aged 30 years and older, also show elevated incidence rates of 17–37/100,000 PY compared to the general population (1–2/100,000 PY). Additionally, anal carcinoma is more common in MSM without HIV (19/100,000 PY), women with high-grade cervical, vaginal, or vulvar dysplasia (6–48/100,000 PY), and individuals undergoing immunosuppressive therapy (3–13/100,000 PY).3 By 2035, a significant increase in anal carcinoma incidence is anticipated in individuals aged 65 years and older.10

Rationale for anal carcinoma screening in people living with HIV

Anal carcinoma screening should be considered as secondary prevention following HPV infection, as high-grade anal dysplasia is a precursor to anal carcinoma.11-13 The 2022 ANCHOR study shows that treating anal dysplasia can significantly reduce the incidence of anal carcinoma.12 Additionally, it has been shown that anal carcinomas detected through screening are more often identified at earlier stages.14

The potential benefits of screening must be balanced against the costs and risks associated with diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. HPV infections and even high-grade anal dysplasia do not necessarily lead to carcinoma; a meta-analysis found that one in 377 cases of high-grade dysplasia transforms into invasive anal carcinoma per year.15 Conversely, spontaneous regression of high-grade anal dysplasia has been observed, with rates of 23.5 and 30 per 100 PY.16, 17 A modelling analysis on diagnostic methods indicated that, among MSM with HIV aged over 35 years – the population with the highest incidence rate – 922 anal cytologies (with annual screening) or 492 cytologies (with triennial screening) are required to prevent one anal carcinoma. The number needed to screen and the number needed to treat to prevent one anal carcinoma were 331 and 153 for annual screening, and 209 and 134 for triennial screening.18 These figures are comparable to those for colorectal cancer screening in the general population.19, 20 and lower than those for cervical cancer screening,21 especially in high-incidence populations. A low CD4+ T-lymphocyte nadir of less than 200 cells/µl or prolonged severe immunodeficiency further increases the risk of anal carcinoma.22 In contrast, HPV vaccination status currently plays a minor role in screening for anal dysplasia due to demographic factors (Recommendation 1).

| Recommendation 1. Screening | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| In people living with HIV, we recommend regular screening for high-grade anal dysplasia and anal carcinoma. | ↑↑ |

Strong consensus 27/28 |

| We recommend treating high-grade anal dysplasia and anal carcinoma. | ↑↑ |

Strong consensus 28/28 |

HISTOPATHOLOGIC AND CYTOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF ANAL DYSPLASIA

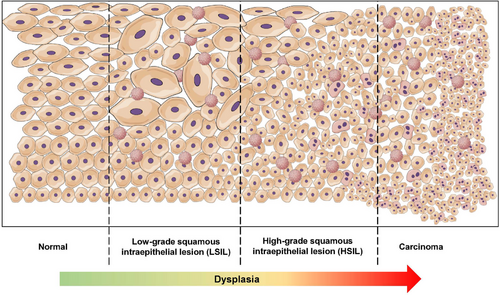

The cytologic classification is based on the revised Bethesda classification of 2015,23 and includes the following categories: normal results (NILM: negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy), low-grade dysplasia (LSIL: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion), high-grade dysplasia (HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion), as well as ASC-US (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance), ASC-H (atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL), and carcinoma. The histopathological classification of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is based on the extent of dysplastic cells in the epithelium and is divided into three grades: AIN1 (involving the lower third of the epithelium), AIN2 (involving the lower two-thirds of the epithelium), and AIN3 (involving the full thickness of the epithelium) (Figure 1, Recommendation 2).24

The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) project recommends considering HPV-associated changes in histological evaluation and proposes a two-tiered classification using “LSIL” and “HSIL” – analogous to the cytological classification.25 Therefore, AIN2 lesions are further evaluated using p16 immunohistochemistry: p16-negative cases are classified as LSIL, while p16-positive cases are classified as HSIL (only lesions showing “en-bloc” staining are classified as “p16-positive”).25 Some data suggests that p16-positive AIN2 HSIL has a lower progression rate compared to AIN3 HSIL, which may limit the applicability of this dichotomous classification.26 An alternative classification differentiates between “low-grade” AIN (LGAIN) and “high-grade” AIN (HGAIN), where HGAIN includes AIN2 and AIN3 lesions, and LGAIN corresponds to AIN1 or lesions with lower grades of dysplasia.27 A comparison of these classifications can be found in Table 1. In 2012, the LAST project introduced the term “superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SISCCA),” referring to a minimally invasive carcinoma defined in the anal canal by the following criteria: (1) invasion depth ≤3 mm measured from the basement membrane, (2) maximum horizontal extent ≤7 mm, (3) of the completely resected lesion.25 No further therapy is required if a lesion meeting these criteria is resected with a margin of 0.5 cm2. Additional details regarding the diagnosis and treatment of (early invasive) anal carcinomas can be found in the corresponding (German-Austrian) S3 guideline.2

| Grade of dysplasia | Cytologic grading of anal dysplasia (Bethesda)23 | Histopathologic grading of anal dysplasia (LAST)25 | Alternative terminology | E6/E7-mRNA positive58, 59 | Host-cell methylation marker positivity (ZNF582, ASCL1, SST)27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undetermined | ASC-US | – | – | 48%–80% | – |

| ASC-H | – | – | – | – | |

| Negative | NILM | Normal | – | 23%–39% | Negative |

| No or low-grade dysplasia | LSIL | Condyloma | LGAIN | 68%–86% | – |

| Low grade dysplasia | LSIL | AIN 1 | ⇔ | ||

| Moderate dysplasia | LSIL | AIN 2, p16 negative | HGAIN/AIN2+ | ↑ | |

| High-grade dysplasia/CIS | HSIL | AIN 2, p16 positive | 95%–100% | ↑↑ | |

| HSIL | AIN 3 | ||||

| Superficial (minimal-invasive) carcinoma | CA | SISCCA | 100% | ↑↑↑ | |

| Invasive carcinoma | CA | CA |

- Abbr.: ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL; ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; AIN, anal intraepithelial neoplasia; CA, carcinoma; CIS, carcinoma in situ; HGAIN, high-grade AIN; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LGAIN, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy; SISCCA, superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

| Recommendation 2. Nomenclature | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| We recommend that the cytological evaluation of anal swabs be conducted according to the revised Bethesda classification of 2015, distinguishing between “Normal” / “NILM (negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy),” “ASC-US (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance),” “ASC-H (atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL),” “LSIL (low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion),” “HSIL (high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion),” and “CA (squamous cell carcinoma).” | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 25/25 |

| We recommend that the histopathological classification distinguish between “Normal mucosa,” “Condylomata acuminata,” “Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) 1,” “AIN 2,” “AIN 3,” and “Carcinoma.” | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| We suggest performing immunohistochemical evaluation using p16 for all AIN 2 lesions. Lesions with “en bloc” positivity should be classified as high-grade dysplasia, while p16 partial or negative lesions should be considered low-grade. | ↑ | Strong consensus 24/24 |

| A dichotomous histopathological reporting as “LSIL” and “HSIL” in addition to “AIN 1,” “AIN 2,” and “AIN 3” according to the criteria of the LAST project may be considered. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| We suggest that, in addition to conventional pathological staging, the histopathological examination of a resected anal carcinoma should assess whether the criteria for a “superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SISCCA)” according to the LAST project are met. | ↑ | Strong consensus 24/25 |

DIAGNOSTICS, TESTING STRATEGIES AND SCREENING METHODS FOR ANAL DYSPLASIA

Anal cytology

Anal cytology is a screening tool known for its ease of use and low cost.28 However, its diagnostic accuracy is limited. Depending on the threshold for referral to HRA, based on the “severity level” of the cytological findings, there may be either good sensitivity with poor specificity, or vice versa.29

Cytology should be collected with the patient in the lithotomy or left lateral position. During the examination, cells from the anal transformation zone are collected using a swab and placed on a slide for evaluation. Patients should be advised to refrain from receptive anal intercourse and using enemas for 24 hours prior to the examination, as these factors can reduce the number of collectable cells. Similarly, contamination from lubricants, Vaseline, or other substances should be avoided for 24 hours before the examination.

To obtain cytology, a nylon flocked swab moistened with saline is inserted into the anal canal and slowly withdrawn with firm, circular motions. The swab is then rolled onto a slide, and a cytological fixative (based on the requirements of the collaborating pathology laboratory) is sprayed onto it.30-33 Alternatively, liquid-based cytology using a cytobrush can be employed. After brushing the transformation zone and surrounding area, the brush is rinsed in a transport container with the carrier solution for at least 30 seconds.34, 35 An adequate cytology smear should contain at least 2,000–3,000 nucleated squamous epithelial cells, corresponding to approximately 1–2 nucleated squamous epithelial cells per field of view under high magnification.36 Note: Properly performing sample collection for anal cytology is generally uncomfortable for the patient (Recommendation 3).

| Recommendation 3. Cytology | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

We suggest against performing an anal cytology as part of anal carcinoma screening if the following apply to the person being examined:

|

↓ | Strong consensus 25/25 |

| We suggest that anal cytology be performed as the first intra-anal examination measure to avoid contamination (e.g., from lubricant, blood, or acetic acid). | ↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

We recommend that anal cytology be performed using:

|

↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| Self-collection of anal cytology may be considered, provided appropriate instructions have been given. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 27/28 |

HPV

Various commercially available polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or hybrid capture systems can be used for the detection of HPV DNA from swabs or biopsies.37-39 Some PCR test systems allow for genotyping of all relevant HR-HPV types.37, 39, 40 While the detection of HR-HPV for predicting AIN in people with HIV is highly sensitive for predicting AIN, it has low specificity.29 HR-HPV can often be detected even in the absence of visible mucosal lesions, which explains the low specificity. Several studies have suggested a combined diagnostic approach using both cytology and HR-HPV detection. For example, one study showed that a stepwise algorithm, starting with cytology followed by an HR-HPV test, improved sensitivity for detecting histological HSIL compared to cytology alone (85% vs. 97%), although specificity remained low (24%–28%).41 (Recommendations 4–6).

| Recommendation 4. HPV-testing | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| A HR-HPV DNA and/or HR-HPV oncogene mRNA detection as part of anal carcinoma screening may be considered in addition to the recommended measures. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 27/27 |

| Alternatively, HR-HPV reflex testing or p16/Ki-67 staining of the anal cytology may be considered starting from an ASC-US result. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 24/25 |

| Recommendation 5. Methylation markers | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| Assessing host cell methylation markers from anal swabs and/or histological material of anal dysplasias may be considered. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 23/23 |

| Recommendation 6. Microbiome | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| We recommend against performing an anal microbiome analysis for the detection of anal dysplasias as part of anal carcinoma screening. | ↓↓ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

Digital anorectal examination

-

Sphincter tone,

-

pain sensitivity,

-

stenosis and scarring,

-

presence of blood or mucus,

-

filling level of the rectal ampulla.

| Recommendation 7. Digital anorectal examination | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| We recommend that a digital anorectal examination be performed at the beginning of a high-resolution anoscopy. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

High resolution anoscopy

High-resolution anoscopy (HRA) is the internationally recognized gold standard for evaluating anal dysplasia. Studies on PLWH have demonstrated that HRA improves the diagnosis of high-grade AIN or anal carcinoma recurrences.44-49 However, it is important to note that the availability of HRA is limited in Germany and Austria (Recommendation 8).

During HRA, the anal canal epithelium is examined under magnification of up to 30 x. An anoscope is inserted into the anal canal, and an appropriate optical device (typically a colposcope) provides sufficient magnification, though devices from ENT/dental or gastroenterological endoscopes can also be used). A detailed methodological description of HRA was published in 2016 by Hillman et al. in collaboration with the International Anal Neoplasia Society.50 Alternatively, gastroenterological endoscopes can be used for anal chromoendoscopy (ACE), as their optical magnification also provides high-quality imaging, as demonstrated in a study involving 211 patients.49 Preparation with an enema or other bowel cleansing is not required, except for ACE.

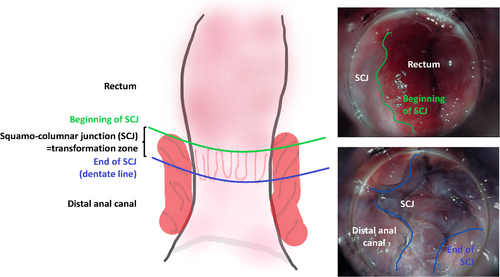

High-resolution anoscopy can be performed either in a standard examination room or in a procedure room/operating room; provided local hygiene guidelines are followed, particularly concerning smoke evacuation during the treatment of HPV-associated lesions. High-resolution anoscopy should always be conducted with assistance. The patient is positioned in the left lateral or lithotomy position. Initially, a gauze soaked in 5% acetic acid (Figure 2) is inserted into the anal canal via the anoscope and left in place for 1–2 minutes. Acetic acid stains dysplastic epithelium white, although it can also stain metaplastic epithelium or scar tissue. For a thorough HRA, the entire anus must be examined. The distal rectum is first inspected, and as the anoscope is withdrawn, the transformation zone, distal anal canal, and perianal region should be fully assessed in their entirety (Figure 3). Lugol's iodine solution may also be applied. Finally, it is crucial to biopsy any unclear lesions.

| Recommendation 8. High-resolution anoscopy | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| We recommend that high-resolution anoscopy (if indicated combined with biopsy for histopathological examination) be performed as the gold standard for the diagnosis of anal dysplasia. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| We recommend that the entire anus and perianus be inspected during high-resolution anoscopy. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| We recommend using 5% acetic acid to stain the epithelium during high-resolution anoscopy. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 24/24 |

| The use of Lugol's solution (iodine test) may be considered during high-resolution anoscopy. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 24/24 |

| We recommend that all epithelial lesions during high-resolution anoscopy be biopsied if high-grade dysplasia cannot be definitively excluded. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| We suggest that, if high-resolution anoscopy is not available, at least a conventional anoscopy without optical magnification should be offered. | ↑ | Strong consensus 25/26 |

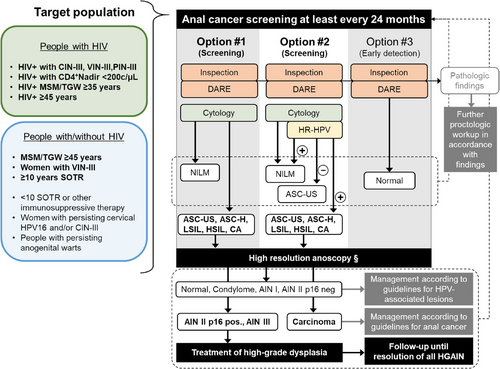

Screening algorithm

If screening is primarily based on cytology (Option #1), HRA is recommended starting from an ASC-US (Figure 4, Recommendations 9, 10). Alternatively, HR-HPV testing may be added (Option #2). In cases of ASC-US with a HR-HPV negative result, HRA may be omitted. For HR-HPV positive results with normal cytology, HRA is not recommended, but follow-up screening should be scheduled within 12 months. If any abnormalities are found during inspection and/or palpation, a conventional proctologic examination, with or without treatment, may be appropriate before performing an HRA (e.g., in cases of fistula or extensive hemorrhoids). If HRA is severely limited or unavailable for further diagnostics, only inspection and digital ano-rectal examination should be performed, and cytology should be omitted (Option #3). This option is primarily for early detection of anal carcinoma and does not aim to detect or treat high-grade anal dysplasia. Option #3 allows the existing healthcare network for PLWH to immediately offer anal carcinoma prevention (early detection) until necessary diagnostic resources or referral networks are established, at which point a shift to Option #1 or #2 should be considered.

| Recommendation 9. Screening population | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

We recommend that anal carcinoma screening is offered to

|

↑↑ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

We suggest that, irrespective of age, anal carcinoma screening is offered to

|

↑ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

| We suggest that screening for anal dysplasia and anal carcinoma be performed at least every 24 months, provided no anal epithelial lesions are present. | ↑ | Strong consensus 27/28 |

If abnormalities are detected during HRA, histopathological diagnostics should be pursued. In cases of AIN II (p16-positive) or AIN III, treatment should always be carried out, as a reduction in anal carcinoma incidence has been demonstrated.12 After treatment, regular follow-up is recommended until all high-grade dysplasia has remitted, with a low-threshold for histological follow-up. Currently, there is no data showing a reduction in anal carcinoma risk by treating low-grade dysplasia. Whether treatment should be applied to histologically confirmed low-grade dysplasia should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Treatment is especially indicated in cases of clinically visible lesions or bothersome condylomata. This approach also allows for complete histopathological evaluation, as high-grade dysplasia can clinically resemble condylomata, particularly in the target population discussed here.51 If a biopsy during follow-up after therapy shows only low-grade dysplasia or condylomata, no further treatment is needed for anal carcinoma prevention.

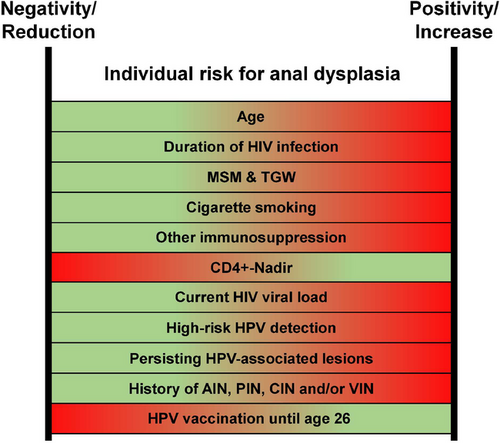

The optimal screening interval is currently undetermined. Recent modelling (with 1–3 year intervals),18 has shown that shorter intervals require more examinations to prevent anal carcinoma, while longer intervals reduce the screening burden but increase the proportion of anal carcinomas that could have been prevented by treating precursors or high-grade dysplasia. Therefore, we recommend offering screening to the target population 12–24 months. Various individual factors can positively or negatively influence the incidence of anal carcinoma. However, the interplay of these factors has not been systematically analyzed to date. As a result, the interpretation of each patient's risk profile is the responsibility of the treating physician, who can adjust the screening intervals on a case-by-case basis. A summary of the known influencing factors is provided in Figure 5.

| Recommendation 10. Screening methods | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

| We recommend that an anal carcinoma screening include an inspection, a digital anorectal examination, and an anal cytology. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 27/27 |

| We recommend that further diagnostics be conducted in case of an abnormal findings during inspection or digital anorectal examination. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

| We recommend that high-resolution anoscopy be performed in case of the following anal cytology findings: “ASC-H,” “LSIL,” and “HSIL.” | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| We suggest that high-resolution anoscopy be performed in case of the following anal cytology finding: “ASC-US.” | ↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

| HR-HPV testing (with or without genotyping) may be considered in addition to cytology. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 26/27 |

| In cases of HR-HPV negativity and “ASC-US” in the anal cytology, further evaluation with high-resolution anoscopy may be omitted. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 25/25 |

| We suggest that if anoscopy is not available, anal carcinoma screening should include inspection and digital anorectal examination only. | ↑ | Strong consensus 25/26 |

TREATMENT OF ANAL DYSPLASIA

High-grade anal dysplasia, including p16-positive AIN II, AIN III, as well as their histological equivalents, HSIL or HGAIN, should be treated. An overview of the different treatment options is provided in Table 2. A detailed discussion and description of all methods can be found in the full version of this guideline (German only, https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/055-007) (Recommendation 11).

| Overview of available treatment options for high-grade anal dysplasia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapy | Mechanism | Application | Efficacy* | Advantages | Disadvantages | Peri-anal | Intra-anal | Reference |

| Ablative methods | ||||||||

| Electrocautery (and Argon-plasma-coagulation) | Thermal destruction with high-frequency voltage (kHz) | Diathermy during anoscopy | 26%–83% |

|

|

+ | + | 57, 60-65 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | Thermal destruction with high-frequency voltage (MHz) | Electrode during anoscopy | 58%–100% |

|

|

− | + | 66-69 |

| Infrared coagulation | Thermal destruction with infrared light | During anoscopy | 38%–74% |

|

|

+ | + | 56, 60, 70, 71, 17, 72,73 |

| Surgical removal | Ablation / excision | Shave or excision | 21%–43% |

|

|

+ | ∼ | 74-76 |

| Trichloroacetic acid 85% | Chemical burn | Application during anoscopy, repeat every 2–4 weeks | 32%–80% |

|

|

+ | + | 63, 65, 77-79 |

| CO2-Laser | Laser vaporization | Targeted use during anoscopy | 50%–63% |

|

|

+ | ∼ | 12, 80-83 |

| Cryotherapy | Liquid nitrogen freezes and destroys tissue | Liquid nitrogen spray during anoscopy, repeat every 4–6 weeks | 60% |

|

|

+ | ∼ | 84 |

| Photodynamic therapy | Light exposure after photosensitization | Photosensitizer infusion 48h prior to light exposure utilizing a probe | 28%–60% |

|

|

+ | ∼ | 85, 86 |

| Immunomodulation, antiviral agents and topical chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Imiquimod 5% | Stimulates interferon and cytokine production | 3 x/week at night for 12 weeks; administered intraanally as a suppository | 24%–77% |

|

|

+ | + | 61, 87-92 |

| 5-Fluorouracil 5% | Topical chemotherapy | 2 x/week 1 g during night for 16 weeks | 17%–88% |

|

|

∼ | ∼+ | 61, 93-95 |

| Cidofovir 1% | Topical antiviral | Daily during night for 5 days, followed by 9 days break. 6 cycles | 15%–63% |

|

|

− | ∼ | 96, 97 |

- * Currently, there is no standardized definition for efficacy following the treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia. In particular, the timing of follow-up assessments varies significantly. The efficacy listed here represents a simplified and generalized interpretation of study results: the rates refer to a complete response at the first post-interventional examination. Further details can be found in the respective references.

- (+), (–), and (∼) indicate the clinical relevance of this treatment method at the specified location according to expert opinion.

| Recommendation 11. Treatment options | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

We suggest treatment of histologically confirmed high-grade anal dysplasia with the following methods:

|

↑ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

The following methods can be considered for treatment of histologically confirmed high-grade anal dysplasia:

|

⇔ | Strong consensus 26/26 |

The following methods can be considered for treatment of histologically confirmed high-grade anal dysplasia on a case-by-case basis:

|

⇔ | Strong consensus 25/25 |

| A combination of different methods for the treatment of histologically confirmed high-grade anal dysplasia may be considered. | ⇔ | Strong consensus 27/27 |

| We recommend follow-up assessments after treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia. | ↑↑ | Strong consensus 27/27 |

| We suggest that the management of histologically diagnosed anogenital warts and low-grade anal dysplasia be conducted according to guidelines for HPV-associated lesions of the anogenital region. | ↑ | Strong consensus 27/27 |

Recommendations for people without HIV

This guideline primarily focuses on PLWH, who are statistically at a significantly higher risk of anal dysplasia and anal carcinoma compared to the general population. However, there are also certain groups of individuals who, despite testing negative for HIV, face a considerably increased risk of anal carcinoma. In Germany and Austria, these groups have not yet been addressed in any existing guidelines. For this reason, the guideline committee has decided to provide recommendations on how the findings of this guideline can be applied to people without HIV (Recommendation 12).

Two studies,52, 53 included in the meta-analysis by Clifford et al., reported an age-dependent incidence rate of anal carcinoma in MSM without HIV, which was 19/100,000 PY.3 For women with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) grade III, the incidence rate of anal carcinoma was 48/100,000 PY. For individuals who had undergone organ transplantation for ten or more years, the incidence was significantly higher: 25/100,000 PY for men and 50/100,000 PY for women.3 Screening for anal carcinoma in people without HIV can only be justified based on the elevated incidence of the disease in these subpopulations. A 2021 study demonstrated that the spontaneous regression of anal dysplasia in MSM, regardless of HIV status, is influenced solely by persistent HPV-16 detection, not by HIV status itself.54 In individuals without HIV, the natural progression or regression of anal dysplasia is less well studied than in PLWH. For example, the ANCHOR Study, which focused solely on PLWH,12 indicates that treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia likely reduces the risk of anal carcinoma in people without HIV as well.

Most of the data on the treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia in people without HIV pertains to electrocoagulation. However, based on mechanistic principles, it can be assumed that the treatment options for high-grade anal dysplasia in PLWH are also applicable to those without HIV.55 Finally, recurrence rates of AIN in people without HIV are reported to be lower than in PLWH.56, 57

| Recommendation 12. People without HIV | Strength | Consensus strength |

|---|---|---|

We suggest offering anal carcinoma screening to the following groups:

|

↑ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

Anal carcinoma screening may be considered for

|

⇔ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

| We suggest that screening for anal carcinoma in individuals without HIV follow methods similar for individuals with HIV. | ↑ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

| We suggest that the treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia in individuals without HIV be approached in a manner analogous to the treatment used for individuals with HIV. | ↑ | Strong consensus 28/28 |

FUNDING

The revision of the guideline was supported by the Clinician Scientist Research Fellowship 2022 of the Austrian Society for Dermatology and Venereology awarded to David Chromy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The conflict-of-interest declarations of all authors can be reviewed online https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/055-007