Board reforms around the world: The effect on corporate social responsibility

Abstract

Research Question/Issue

This study examines the effects of major board reforms on firms' corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance in countries around the world.

Research Findings/Insights

Using a difference-in-differences design, we find robust evidence that worldwide board reforms can have significant effects on various stakeholders, resulting in increased firm CSR performance in both the environmental and social dimensions. Relative to countries that have implemented comply-or-explain reforms, countries with rule-based reforms tend to drive the increase in CSR performance post-reform. Our results hold for both first board reforms and major reforms, across different types of reforms, and across various dimensions of CSR performance. In addition, the effect of reforms on CSR performance is more pronounced for firms with higher levels of institutional ownership or lower levels of insider ownership and in countries with weaker CSR awareness and more stringent legal and regulatory environments. Further analyses show that reforms strengthen the relationship between CSR performance and future financial performance. Finally, we explore the possible mechanism through which board reforms could have a significant effect on firms' CSR performance. We find that board reforms increase a firm's likelihood of integrating CSR criteria in executive compensation.

Theoretical/Academic Implications

The findings of this study suggest that worldwide board reforms that aim to increase shareholders' value can also have significant effects on various stakeholders, resulting in increased firm CSR performance in both the environmental and social dimensions, a non-financial dimension of firm performance.

Practitioner/Policy Implications

Our evidence suggests that increases in CSR performance are an important channel through which board reforms can increase shareholder value. In addition, our findings suggest that the effectiveness of reforms on CSR varies with both firm- and country-level characteristics related to the relative influence of external shareholders. Thus, this study offers insights to policy makers interested in enhancing CSR performance in their country.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, numerous countries have undertaken corporate governance reforms to strengthen the mechanisms through which shareholders ensure a financial return on their investments (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997).1 Supporting the importance and effectiveness of such reforms, recent studies have documented that major corporate governance reforms implemented in many countries since the late 1990s have increased shareholder wealth (e.g., Fauver et al., 2017; Kim & Lu, 2013). Although approaches to reform vary across countries, most reforms focus on board-related practices, such as imposing greater board independence, promoting audit committee and auditor independence, and separating the positions of chairman and chief executive officer (CEO). As boards are the fundamental governance mechanism of corporations, board reforms are thus considered as the major approach to address corporate governance issues. Thus, in this study, we examine whether country-level board reforms affect corporate performance in environmental and social dimensions (hereafter, corporate social responsibility [CSR] performance).

CSR performance is a critical issue globally and is a primary corporate governance concern for many firms.2 Indeed, an increasing number of investors are integrating CSR dimensions into their investment decisions based on both financial and social considerations (Dyck et al., 2019). The stakeholder view of CSR suggests that CSR represents an important tool for long-term shareholder value creation (e.g., El Ghoul et al., 2017; Ferrell et al., 2016; Lins et al., 2017; Servaes & Tamayo, 2013). Following this view, we predict that investors are likely to exert a greater influence on improving CSR policies to enhance long-term shareholder value due to strengthened governance practices following a country's corporate board reform (Oh et al., 2018).

However, although CSR has become an important business practice in recent years, opponents believe that it can be an agency cost with the potential to limit shareholder value (e.g., Bénabou & Tirole, 2010; Cheng et al., 2016; Friedman, 2007; Krüger, 2015).3 More specifically, this perspective argues that CSR investment represents costly diversion of scarce resources and that managers engaging in CSR are serving their own interests at the expense of shareholders. From this perspective, improved board oversight and monitoring resulting from strengthened corporate governance practices would presumably reduce firms' CSR investment due to agency problems. An alternative prediction is that corporate board reforms may have no effect on CSR performance. CSR pertains to a broad array of issues (such as reducing environmental emissions, providing employees with adequate training and a safe working environment, and maintaining the company's reputation and image) related primarily to non-financial stakeholders. Thus, on a conceptual level, it seems unlikely that corporate board reforms that deal with audit committee and auditor independence, board independence, or separating the positions of the chairman and CEO would directly affect corporate CSR performance. Overall, these discussions suggest that the ultimate effect of corporate board reforms on CSR is an empirical question.

Although there is a growing interest in the effects of corporate governance on CSR performance (Arora & Dharwadkar, 2011; Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Johnson & Greening, 1999), the empirical evidence on the relationship between corporate governance and CSR has been equivocal (Endrikat et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2018). This lack of consistency in the previous findings thus calls for further investigation that helps us better understand the relationship between corporate governance and CSR. Given the possible endogeneity concerns in examining the relationship between corporate governance and CSR (Ferrell et al., 2016; Harjoto & Jo, 2011; Jamali et al., 2008; Jo & Harjoto, 2012), the quasi-experiment provided by the worldwide adoption of corporate board reforms4 can presumably help us answer the questions of (1) whether and how major corporate board reforms in a country affect firms' CSR performance, (2) whether and how the effect of reforms on firms' CSR performance varies with cross-sectional differences across reform-, firm-, and country-level characteristics, and (3) what are the possible channels through which board reforms can affect firms' CSR performance.

To test whether corporate board reforms affect firms' CSR investment, we use data from Thomson Reuters ASSET4 to construct firm-level CSR measures.5 Based on a large sample of more than 20,000 observations from 34 countries with firms' CSR performance data available, we examine changes in firms' CSR performance following a country's implementation of major corporate board reforms. Using a difference-in-differences (DID) research design, we find that, on average, firms' CSR performance improves after reforms. Our results hold for both first board reforms and major reforms, across different types of reforms (including reforms focusing on the improvement of board independence, enhancing audit committee and auditor independence, and encouraging the separation of the chairman and CEO roles), and across different dimensions of CSR performance (environmental and social dimensions). This finding suggests that corporate board reforms implemented primarily to ensure financial returns to shareholders (e.g., by improving board oversight/monitoring) also appear to have a positive spillover effect for non-financial stakeholders.

In addition, we find that the positive effect of reforms on CSR is mainly driven by firms in countries with rule-based reforms and in countries with lower levels of CSR awareness in general. Additional results suggest that reforms have a greater effect on CSR in countries with a more stringent legal and regulatory environment. Finally, consistent with studies showing the importance of CSR to shareholder wealth (e.g., Dhaliwal et al., 2011; Dyck et al., 2019; Lins et al., 2017), we find that the effect of reforms on CSR is more pronounced for firms with higher levels of institutional ownership or lower levels of insider ownership.

Although the above findings support the argument that corporate board reforms positively affect firms' CSR, they do not indicate whether increased post-reform CSR investment enhances shareholder value. That is, firms' increased CSR investment could represent symbolic CSR activities instead of substantive CSR initiatives (Cheng et al., 2016; Cronqvist & Yu, 2017; Masulis & Reza, 2015). For example, a higher level of CSR investment could result from managers' symbolic response to increasing pressure from outside directors, who tend to pay more attention to non-financial CSR performance than to corporate financial performance (Ibrahim & Angelidis, 1995; Post et al., 2011). Thus, we next explore whether and how reforms affect the relationship between CSR and future financial performance. Our results indicate that relative to firms domiciled in countries that did not implement reforms during the sample period, firms domiciled in countries with reforms tend to exhibit a stronger relationship between CSR investment and future financial performance. This finding is consistent with the view that increased CSR investment after reforms is likely perceived by shareholders as value-enhancing.

Taken together, our findings support the positive role played by a country's implementation of corporate board reforms in fostering firms' substantive CSR investment/initiatives. This finding is also in line with the argument that the role of corporate governance is to reduce managerial “short-termism” and thus improve value-enhancing stakeholder investments (Dyck et al., 2020). The finding of a stronger positive association between CSR and firms' future financial performance in the post-reform period further supports the value-enhancing view of CSR activities (Boubakri et al., 2016; El Ghoul et al., 2017). In summary, our evidence suggests that strengthened corporate governance practices to enhance shareholder value have a positive externality effect on performance toward stakeholders.

Finally, we further explore the channels through which board reforms could have a significant effect on firms' CSR performance. Recent studies show that an increasing number of firms worldwide tend to strengthen their corporate governance by linking executive compensation to CSR criteria as such practices can incentivize managers to improve firm's CSR, which in turn creates long-term firm value (Flammer et al., 2019; Tsang, Wang, et al., 2020). Supporting this argument, in our study, we find that board reforms increase a firm's likelihood of integrating non-financial CSR criteria in executive compensation. This finding suggests that one important channel through which board reforms affect firms' CSR performance is the increased adoption of this emerging executive compensation design, which aims to increase managers' incentive to improve firms' CSR.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we add to the literature on the determinants of CSR performance. More specifically, prior studies find that national-level institutional factors (such as culture and investor protection) significantly shape firms' CSR practices and their perceived value to investors (Boubakri et al., 2016; Cahan et al., 2016; El Ghoul et al., 2017; Ioannou & Serafeim, 2012; Orij, 2010; van der Laan Smith et al., 2005; van der Laan Smith et al., 2010).6 This study shows that country-level corporate board reforms play an important role in encouraging firms' CSR investment and thus adds to the literature examining how cross-country differences affect CSR initiatives. Examining the effect of corporate governance on CSR performance in a multi-country context also offers other advantages. For example, given that the effectiveness of corporate governance mechanisms likely varies with other country-level institutions (Ioannou & Serafeim, 2012; Jain & Jamali, 2016; La Porta et al., 1998; Matten & Moon, 2008), an international study can also shed light on how corporate governance practices interact with other formal institutions to influence managerial behavior such as CSR investment.

Second, this study contributes to a growing body of literature that examines the impact of corporate governance-related reforms on firm outcomes (Bae, El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Zheng, 2020; Bae, El Ghoul, Kang, & Tsang, 2020; Fauver et al., 2017; Kim & Lu, 2013). While earlier research emphasizes the role of corporate governance in resolving the agency conflicts between managers and shareholders (Berle & Means, 1932), more recent studies call for research to investigate the governance consequences and spillovers for non-financial stakeholders (Gill, 2008; Harjoto & Jo, 2011; Jo & Harjoto, 2012; Windsor, 2006). Moreover, the increase in the number of incidents of corporate frauds and scandals over the past decades has broadened the concept of corporate governance beyond simply dealing with agency conflicts toward adopting a sustainable and socially responsible agenda (Elkington, 2006). In response to this call, our study shows that corporate governance reforms add value to stakeholders by fostering firms' substantive CSR investment.

Finally, our study explores the mechanisms through which corporate board reforms could have an impact on CSR outcomes. Prior literature has thus far produced mixed findings regarding the effect of individual firms' corporate governance practices on CSR behavior (Coffey & Fryxell, 1991; David et al., 2007; Jo & Harjoto, 2012; Waddock & Graves, 1997), probably due to the interdependence of various levels of governance attributes. We provide evidence that corporate board reforms in a country will foster firms' long-term orientation through linking executive compensation to CSR performance. This finding complements Jain and Jamali (2016), who suggest that firm-level governance changes may be unlikely to influence CSR outcomes successfully unless they are complemented by other mechanisms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the related literature and presents the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Data and sample statistics are summarized in Section 4. Section 5 presents the main empirical results. Section 6 discusses additional analyses. Section 7 concludes the study.

2 RELATED LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

The role of corporate governance in resolving conflicts between inside and outside investors has been extensively discussed in the literature. Overall, the literature suggests that corporate governance affects management oversight and firm performance (Dahya & McConnell, 2007; Dahya et al., 2002; Li, 2014; Zhang, 2007). Although findings based on a single country are inconclusive regarding the valuation consequences of firm-level governance attributes (Hermalin & Weisbach, 2003), numerous international studies show a positive relationship between governance quality and firm performance (e.g., Aggarwal et al., 2009; Dahya et al., 2008). Further supporting the effects of corporate governance practices on firm performance, Fauver et al. (2017) document that major board reforms implemented in countries around the world increase firm value.

The literature outlines two perspectives on CSR. The positive view of CSR posits that companies engage with stakeholders to enhance shareholder value. In line with this view, studies show that superior CSR performance is associated with greater access to external finance (e.g., Cheng et al., 2014; Dhaliwal et al., 2011; Goss & Roberts, 2011), reduced cost of capital, and higher valuation (e.g., El Ghoul et al., 2011; Galema et al., 2008; Ng & Rezaee, 2015). Further supporting this view, the literature provides examples of the mechanisms through which CSR investment can positively affect shareholder wealth, such as customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and greater institutional ownership (e.g., Dimson et al., 2015; Dowell et al., 2000; Edman, 2011; Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006; Servaes & Tamayo, 2013). More recently, Lins et al. (2017) suggest that a firm's CSR activities can be considered a vehicle for building social capital and thus protecting firm value during a period of financial crisis.

In contrast, the negative view of CSR holds that CSR signals the presence of agency problems in a firm (Friedman, 2007). According to this line of thought, insiders (e.g., managers or controlling shareholders) invest in CSR activities for their own benefit, such as to enhance their reputation with key stakeholders at the expense of shareholders (e.g., Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Bénabou & Tirole, 2010; Cespa & Cestone, 2007; Masulis & Reza, 2015; Prior et al., 2008). Empirical studies provide evidence supporting this alternative view of CSR. For example, using an event study, Krüger (2015) shows that investors respond negatively to positive CSR news subject to a high agency problem concern. Ioannou and Serafeim (2015) explore the effect of CSR from the perspective of analysts and find that analysts issue more pessimistic recommendations for firms with high CSR ratings when they perceive firms' CSR as an agency cost.

CSR is an expensive investment that can incur substantial costs in the near term with uncertain financial returns in the long run (e.g., Chen et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020; Manchiraju & Rajgopal, 2017). Although many studies have examined the link between CSR and firm value, the ongoing debate and inconclusive evidence suggest that firms' CSR investments are likely associated with uncertain future returns and thus can be perceived as a form of risk-taking.7 This view is further supported by the fact that firms' CSR activities tend to be broad in scope (e.g., covering multiple dimensions, including environment, products, employees, communities, etc.), varying in form (e.g., proactive or reactive), and forward-looking in nature. As a result, relative to other forms of investment, such as capital expenditures, the financial returns of CSR tend to be more difficult to quantify, as the outcomes may be more diffuse and uncertain (Wang et al., 2016).

Freeman (1984) suggests that corporate executives should consider the interests of a broader range of stakeholders, including governments, competitors, consumer and environmental advocates, the media, and others. Harjoto and Jo (2011, p. 46) argue that if Freeman's (1984) stakeholder theory is valid, firms with more effective governance are more likely to engage in CSR activities. In a similar vein, Jo and Harjoto (2012, p. 54) observe that “stakeholder theory states that firms should use CSR as an extension of effective corporate governance mechanisms to resolve conflicts between managers and non-investing stakeholders.” Jo and Harjoto (2012) use a number of traditional corporate governance measures, including percentage of independent board members and percentage of institutional shareholding, and show that their 1-year lagged corporate governance measures are associated with the number of firms' CSR strengths.

Board reforms implemented in a country are typically followed by higher corporate governance requirements, which help align corporate insiders' interests with those of shareholders.8 In this study, following prior studies (e.g., Freeman, 1984; Harjoto & Jo, 2011; Jo & Harjoto, 2012), we posit that corporate board reforms (which presumably improve corporate governance practices in a country) may affect CSR through various mechanisms, which can lead to contrasting expectations. The positive view of CSR suggests that better corporate governance after reforms should encourage firms to increase CSR to enhance shareholder value. Consistent with this prediction, research shows that well-governed firms that suffer less from agency problems engage in more CSR (Ferrell et al., 2016; Harjoto & Jo, 2011; Jo & Harjoto, 2012). In addition, better corporate governance may strengthen the influence of outside board members, who tend to value firms' broader societal impact, and thus induce higher levels of CSR investment (Ibrahim & Angelidis, 1995; Post et al., 2011). Following a similar line of reasoning, Dyck et al. (2020) hypothesize that outside investors need an effective corporate governance mechanism to obtain control rights and improve firm environmental sustainability. According to these studies, we predict that reforms may have a positive effect on CSR.

An alternative prediction leads to a negative relationship between reforms and CSR. As discussed above, according to the negative view of CSR, CSR activities indicate agency problems in the firm. If reforms constrain managers' flexibility through a greater level of board oversight that prevents managers from investing in CSR activities for their personal benefit, firms would be expected to have a lower level of CSR investment after the implementation of reforms. In addition, studies suggest that stricter corporate governance reforms could reduce managers' risk-taking incentive following reforms (e.g., Bargeron et al., 2010; Cohen & Dey, 2013). Thus, to the extent that reforms improve the monitoring of corporate insiders by shareholders and expand the liability associated with risk-taking activities,9 managers might be less likely to invest in CSR initiatives, which would result in lower CSR investment after reform.

Based on the discussion above, we formulate competing hypotheses as follows:

H1a.Corporate governance reforms have a positive effect on firms' CSR investment.

H1b.Corporate governance reforms have a negative effect on firms' CSR investment.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

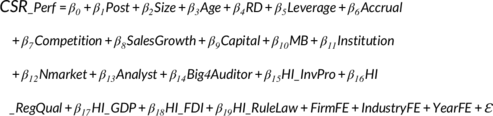

Because several countries have implemented multiple board reforms during our sample period, in examining the effect of board reforms on CSR, we thus focus on major board reform of a country. To test the effect of reforms on firms' CSR, we use a DID design and regress firms' CSR investment on Post, an indicator variable that captures the post-reform period in which board reform was adopted by a country. Because each country implements reform in different years, we follow previous studies (e.g., Bae, El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Zheng, 2020; Bae, El Ghoul, Kang, & Tsang, 2020; Fauver et al., 2017) and use a staggered DID research design that involves multiple treatment groups and periods. Accordingly, we include both firm fixed effects and year fixed effects to identify the within-firm and within-year changes in CSR activities between the treatment and control firms when their countries initiate reforms. As is common in the literature, all firms from countries without reforms as of a given time are implicitly taken as the benchmark group (Bertrand et al., 2004; Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2003). Since we include firm fixed effects in the model, the coefficient on the treatment indicator (i.e., Reform in the traditional DID) is suppressed because it is a linear combination of firm fixed effects. In other words, there is no within-firm variation of this variable.10

(1)

(1)We include an array of control variables documented in the literature as potential determinants of CSR. Larger firms and firms with an established history have more resources to invest in CSR (McGuire et al., 1988; McWilliams & Siegel, 2000). Thus, we control for firm size (Size, measured as the natural logarithm of total assets) and Age (measured by the natural logarithm of the number of years since incorporation). RD is research and development expenditures scaled by net sales. Leverage is the ratio of total debt to total assets, a proxy for lenders' concerns about a firm's risk and CSR performance (Goss & Roberts, 2011). We also follow Jiraporn et al. (2014) and control for capital intensity, measured by Capital (the ratio of capital expenditures to total assets). Moreover, we control for growth opportunities (measured by MB, the market-to-book ratio of equity, and SalesGrowth, the annual sales growth rate), as firms with higher growth opportunities may have fewer resources for CSR activities but may also have greater incentives to use CSR to reduce information asymmetry (Dhaliwal et al., 2011). Competition is measured by the Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which is computed as −1 times the sum of the squared market shares in the sales of a firm's industry, with industries being defined based on their two-digit SIC codes.

We include two measures of financial reporting quality, Accrual and Big4Auditor, as CSR engagement could either decrease or increase with earnings management practices (Chih et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012; Prior et al., 2008). Accrual is a measure of firm-level financial opacity measured by country–industry–year–adjusted total accruals based on Bhattacharya et al. (2003). Big4Auditor is an indicator variable equal to 1 if a firm's auditor is a Big Four auditor, and 0 otherwise. Cross-listing (measured by Nmarket, the total number of stock exchanges on which a firm is listed, including its home country listing), analyst coverage (measured by Analyst, the number of analysts following a firm during the current year), and institutional ownership (measured by Institution, the proportion of shares held by all types of institutional investors at the end of the year) are also shown to be associated with CSR performance (Boubakri et al., 2016; Dhaliwal et al., 2011). Following Lys et al. (2015), we include Cash (cash divided by total assets) and Advertising (annual advertising expense divided by net sales) because firms with higher values for these variables tend to commit more resources to CSR.

In addition to firm-level control variables, we include several country-level variables to control for the potential impact of country-level macroeconomic characteristics on CSR. Specifically, we use two variables to capture the stringency or development of a country's legal and regulatory environment: InvPro is the investor protection index that measures the strength of investor protection in a country, and RegQual is the regulatory quality index that measures the level of credit market regulations, labor market regulations, and business regulations in a country.12 We also control for a country's economic development measured by the natural logarithm of real gross domestic product per capita (GDP), annual net flows of foreign direct investment (FDI), and annual rule of law index (RuleLaw). Finally, we include industry, year, and firm fixed effects to account for variation in CSR that is potentially driven by unobserved heterogeneities across industries, years, and firms, respectively.13 Appendix A provides a summary of the variable definitions.

4 SAMPLE SELECTION AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

4.1 Data source and sample selection

We first identify countries that have experienced major board reforms following Fauver et al. (2017) and Kim and Lu (2013).14 For each reform initiative, we obtain information on the year in which a reform became effective, the types/objectives of the reform involved (e.g., encouraging board independence, promoting audit committee and auditor independence, and separating the chairman and CEO positions), and the reform approach (rule-based or comply-or-explain). Appendix B provides detailed information on the implementation years, types, and approaches of the major reforms in each country. The sample period starts in 2002, the earliest year for which we can obtain CSR rating data from the Thomson Reuters ASSET4 ESG database. The ASSET4 database has a large number of international firms, and it scores firms on financial, environmental, social, and governance dimensions based on objective, publicly available information according to Thomson Reuters (e.g., stock exchange filings, annual financial and sustainability reports, non-governmental organizations' websites, and news sources).15 We focus on CSR ratings in the environmental and social dimensions and use the average rating of both dimensions as an aggregated measure of CSR.

In our sample, all 34 countries with reforms implemented since 1998 are covered by ASSET4. However, because ASSET4 has provided CSR rating data since 2002, to ensure the existence of at least a 1-year pre-reform window to examine the changes in firms' CSR, the sample period for our treatment countries starts in 2003 (three countries, France, Singapore, and the United States, implemented reforms in 2003). Our sample period ends in 2011 because all of the countries in our sample completed their reforms by 2007. Using 2011 as the end year ensures a sufficient post-reform period to conduct the analysis. We further exclude firms from financial industries (SIC codes 6000–6411).16 Finally, we exclude firm–year observations with missing data for the control variables. Our final sample consists of 20,293 firm–year observations associated with 3,514 firms from 34 countries (12,343 observations from countries with reforms implemented since 2003 and 7,950 observations from countries with reforms implemented before 2003). Among the 34 sample countries, 15 countries with major board reforms implemented during our sample period (five of which adopted rule-based reforms) are our treatment sample (see Figure 1).17

4.2 Sample distribution and descriptive statistics

Panel A of Table 1 presents the sample distribution and average CSR rating by country. The treatment group includes countries that initiated reforms during our sample period. As discussed, countries that implemented reforms in 2002 or before do not experience any reform changes during our sample period. Thus, these countries are the benchmark group.18 Both the treatment and benchmark groups exhibit large variations in the number of firm–year observations across countries, with the United States and Japan representing the largest samples in the treatment and benchmark groups, respectively. Panel B of Table 1 reports the sample distribution and average CSR rating by year. There is an increasing trend in the number of firms included in the sample, from 784 firms (3.9%) in 2002 to 3,176 firms (15.7%) in 2011. The smaller number of firms included in our sample before 2004 is mainly due to the change in the ASSET4 company universe. The increased sample size also justifies the need for a constant sample analysis when conducting empirical tests using panel data. In Table 1, Panel A, we also present the comparative statistics of firms' CSR ratings across countries for a constant sample, in which we require a firm to appear at least once in both the pre- and post-reform periods.

| Panel A. Sample distribution by country |

| Full sample | Constant sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Obs. | CSR_Perf | Obs. | CSR_Perf | Pre-reform | Post-reform | Diff (post–pre) |

| Treatment group (reform = 1) | |||||||

| Australia | 1,047 | 0.385 | 30 | 0.847 | 0.841 | 0.849 | 0.009 |

| Austria | 150 | 0.539 | 87 | 0.566 | 0.629 | 0.538 | −0.092* |

| Belgium | 209 | 0.506 | 162 | 0.501 | 0.468 | 0.522 | 0.054 |

| Canada | 1,349 | 0.372 | 118 | 0.776 | 0.751 | 0.789 | 0.038 |

| France | 677 | 0.743 | 388 | 0.810 | 0.729 | 0.831 | 0.102*** |

| Finland | 203 | 0.710 | 140 | 0.723 | 0.71 | 0.728 | 0.018 |

| Hong Kong | 519 | 0.342 | 279 | 0.424 | 0.348 | 0.454 | 0.106*** |

| Indonesia | 51 | 0.551 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Italy | 304 | 0.602 | 269 | 0.597 | 0.549 | 0.636 | 0.087** |

| Netherlands | 277 | 0.682 | 175 | 0.746 | 0.646 | 0.798 | 0.153*** |

| Norway | 155 | 0.650 | 142 | 0.640 | 0.603 | 0.663 | 0.060 |

| Singapore | 287 | 0.347 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Spain | 333 | 0.705 | 284 | 0.720 | 0.638 | 0.792 | 0.154*** |

| Sweden | 388 | 0.633 | 364 | 0.648 | 0.596 | 0.691 | 0.096*** |

| United States | 6,394 | 0.434 | 3,412 | 0.505 | 0.358 | 0.546 | 0.188*** |

| Subtotal | 12,343 | 0.467 | 5,850 | 0.569 | 0.487 | 0.600 | 0.113*** |

| Benchmark group (reform = 0) | |||||||

| Brazil | 177 | 0.580 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chile | 49 | 0.446 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| China | 308 | 0.277 | 10 | 0.686 | 0.476 | 0.776 | 0.300*** |

| Denmark | 176 | 0.547 | 137 | 0.552 | 0.480 | 0.583 | 0.103** |

| Greece | 139 | 0.461 | 91 | 0.439 | 0.596 | 0.691 | 0.096*** |

| Germany | 566 | 0.656 | 301 | 0.727 | 0.671 | 0.752 | 0.082** |

| India | 157 | 0.603 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Israel | 32 | 0.261 | 10 | 0.280 | 0.151 | 0.336 | 0.185 |

| Japan | 2,828 | 0.537 | 240 | 0.759 | 0.673 | 0.796 | 0.124*** |

| Malaysia | 96 | 0.419 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mexico | 96 | 0.472 | 10 | 0.905 | 0.903 | 0.905 | 0.002 |

| Philippines | 37 | 0.392 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Poland | 42 | 0.368 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Portugal | 69 | 0.736 | 28 | 0.792 | 0.673 | 0.831 | 0.158*** |

| South Korea | 239 | 0.605 | 10 | 0.884 | 0.794 | 0.923 | 0.129*** |

| Switzerland | 540 | 0.573 | 351 | 0.663 | 0.611 | 0.686 | 0.075** |

| Turkey | 53 | 0.505 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Thailand | 43 | 0.558 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| United Kingdom | 2,303 | 0.607 | 860 | 0.738 | 0.715 | 0.749 | 0.034** |

| Subtotal | 7,950 | 0.558 | 2,048 | 0.700 | 0.654 | 0.721 | 0.068*** |

| Overall | 20,293 | 0.503 | 7,898 | 0.603 | 0.535 | 0.630 | 0.095*** |

| Panel B. Sample distribution by year | |||||||

| Year | Full sample | Constant sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | CSR_Perf | Obs. | CSR_Perf | |

| 2002 | 784 | 0.494 | 775 | 0.495 |

| 2003 | 791 | 0.498 | 782 | 0.498 |

| 2004 | 1,517 | 0.487 | 844 | 0.569 |

| 2005 | 1,862 | 0.490 | 855 | 0.566 |

| 2006 | 1,878 | 0.493 | 843 | 0.564 |

| 2007 | 2,029 | 0.505 | 794 | 0.611 |

| 2008 | 2,392 | 0.509 | 774 | 0.650 |

| 2009 | 2,735 | 0.507 | 762 | 0.685 |

| 2010 | 3,129 | 0.509 | 745 | 0.700 |

| 2011 | 3,176 | 0.511 | 724 | 0.714 |

| Overall | 20,293 | 0.503 | 7,898 | 0.603 |

| Panel C. Sample distribution by industry | ||||

| Industry | Full sample | Constant sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | CSR_Perf | Obs. | CSR_Perf | |

|

1,432 | 0.463 | 307 | 0.667 |

|

912 | 0.557 | 362 | 0.613 |

|

925 | 0.539 | 433 | 0.574 |

|

923 | 0.700 | 432 | 0.728 |

|

656 | 0.521 | 335 | 0.633 |

|

1,249 | 0.455 | 388 | 0.647 |

|

493 | 0.661 | 193 | 0.720 |

|

697 | 0.561 | 227 | 0.626 |

|

756 | 0.567 | 324 | 0.621 |

|

527 | 0.609 | 252 | 0.647 |

|

727 | 0.663 | 315 | 0.772 |

|

671 | 0.518 | 344 | 0.571 |

|

105 | 0.498 | 39 | 0.530 |

|

1,714 | 0.468 | 696 | 0.513 |

|

1,870 | 0.498 | 790 | 0.605 |

|

1,233 | 0.599 | 550 | 0.688 |

|

518 | 0.448 | 177 | 0.545 |

|

1,260 | 0.441 | 527 | 0.565 |

|

181 | 0.558 | 96 | 0.661 |

|

1,751 | 0.358 | 521 | 0.496 |

|

1,311 | 0.386 | 460 | 0.463 |

|

382 | 0.351 | 130 | 0.465 |

| Overall | 20,293 | 0.503 | 7,898 | 0.603 |

- Note: Panels A-C of this table present the sample distributions by country, year, and industry, respectively. The industry definition of Panel C is based on the industry classification of Barth et al. (1998). We exclude firms in the financial industry (SIC codes 6000–6411) from our sample. In the constant sample, we require a firm to appear for at least 1 year in both pre- and post-reform periods.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Our results indicate that for treatment countries, on average, firms' CSR rating improves from 0.487 to 0.600 (difference = 0.113, t-value = 13.381) (see Panel A). In comparison, for the benchmark countries, firms' CSR ratings are 0.721 on average in the post-reform period relative to an average of 0.654 in the pre-reform period (difference = 0.068, t-value = 5.837). Thus, the results of the univariate analysis of the treatment and benchmark countries provide preliminary support for a positive effect of reforms on firms' CSR.

In Panel B of Table 1, we also observe a gradual improvement in CSR rating during the sample period, which is consistent with the increasing effort that firms devote to their CSR initiatives over time. Panel C of Table 1 reports the sample distribution and average CSR rating by industry based on the 22 industry classifications of Barth et al. (1998). Firms in the chemicals industry (#4) and the manufacturing industry (#7 rubber/glass and #11 transport equipment) have the highest CSR ratings, followed by firms in the utilities industry (#16), which is consistent with the importance of CSR activities in these industries. In contrast, firms in the insurance (#20) and services (#21) industries tend to have lower CSR ratings.

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics of the key variables used in the main analyses. To reduce the influence of outliers, all of the continuous variables are winsorized at the top and bottom one percentile. The average CSR rating is around 0.5, which is comparable to the findings of prior studies (e.g., El Ghoul et al., 2017; Ioannou & Serafeim, 2012; Lys et al., 2015).

| Variable | Mean | Std. dev. | 25% | 50% | 75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR_Perf | 0.503 | 0.295 | 0.215 | 0.477 | 0.800 |

| ENV_Perf | 0.507 | 0.318 | 0.180 | 0.472 | 0.846 |

| SOC_Perf | 0.499 | 0.309 | 0.199 | 0.485 | 0.806 |

| Tobin's Q | 1.686 | 1.025 | 1.069 | 1.353 | 1.913 |

| Post | 0.907 | 0.290 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Reform | 0.608 | 0.488 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Size | 8.592 | 1.382 | 7.688 | 8.513 | 9.489 |

| Age | 3.790 | 0.947 | 3.135 | 3.932 | 4.554 |

| Leverage | 0.560 | 0.204 | 0.425 | 0.570 | 0.698 |

| Accrual | 0.000 | 0.097 | −0.034 | 0.000 | 0.035 |

| MB | 2.616 | 2.798 | 1.162 | 1.879 | 3.147 |

| Competition | −0.253 | 0.248 | −0.352 | −0.146 | −0.082 |

| Cash | 0.095 | 0.097 | 0.026 | 0.064 | 0.130 |

| SalesGrowth | 0.140 | 0.322 | −0.013 | 0.096 | 0.225 |

| Advertising | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Capital | −0.052 | 0.052 | −0.068 | −0.038 | −0.017 |

| RD | 0.017 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Nmarket | 1.308 | 0.653 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Institution | 0.379 | 0.342 | 0.005 | 0.297 | 0.690 |

| Analyst | 12.84 | 11.23 | 0.000 | 12.000 | 20.000 |

| Big4Auditor | 0.776 | 0.417 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| InvPro | 7.107 | 1.487 | 5.850 | 8.000 | 8.300 |

| RegQual | 7.870 | 0.704 | 7.600 | 7.900 | 8.400 |

| GDP | 8.001 | 1.339 | 7.178 | 7.934 | 9.480 |

| FDI | 3.235 | 6.694 | 1.270 | 2.370 | 3.450 |

| RuleLaw | 1.464 | 0.451 | 1.330 | 1.580 | 1.720 |

- Note: This table presents the summary statistics for the main variables used in regression analyses. All variables are defined in Appendix A.

Next, we conduct a bivariate analysis using the Pearson correlation coefficients of the major variables used in our test. Untabulated results indicate that our variable of interest, the post-reform indicator Post, is positively and significantly correlated with the three measures of CSR: CSR_Perf (0.024), ENV_Perf (0.030), and SOC_Perf (0.014). This provides preliminary evidence supporting Hypothesis 1a that firms' CSR investment improves after board reforms. The results also show that CSR rating is positively correlated with firm size, firm age, R&D expenditures, leverage, capital intensity, institutional ownership, cross-listing, analyst coverage, and Big Four auditor. These findings are generally consistent with the literature.

5 REGRESSION RESULTS

5.1 Baseline results

Table 3 reports the regression results for the competing hypotheses regarding the effect of reforms on CSR. Column (1) shows that the coefficient on Post is positive and statistically significant (coefficient = 0.026, p < .01) when the overall CSR rating (CSR_Perf) is the dependent variable. Columns (2) and (3) present the results when the dependent variable is measured by environmental rating (ENV_Perf) and by social rating (SOC_Perf), respectively. Again, the coefficients on Post are both positive and significant (p < .01).19 Thus, the results in Table 3 support Hypothesis 1a that a country's implementation of reforms improves firms' CSR investment on average. This finding supports the conclusion that board reforms strengthen the monitoring role of the board and empower stakeholders/investors outside of the firms to make changes in their corporate decision-making.

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) ENV_Perf | (3) SOC_Perf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post | 0.026*** (0.009) | 0.031*** (0.011) | 0.021* (0.011) |

| Size | 0.024*** (0.007) | 0.024*** (0.008) | 0.024*** (0.007) |

| Age | 0.031 (0.021) | 0.039 (0.025) | 0.023 (0.022) |

| Leverage | −0.038 (0.030) | −0.015 (0.037) | −0.062** (0.027) |

| Accrual | −0.006 (0.010) | −0.009 (0.013) | −0.003 (0.010) |

| MB | 0.001* (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002* (0.001) |

| Competition | −0.017 (0.028) | −0.021 (0.038) | −0.012 (0.029) |

| Cash | −0.009 (0.031) | 0.001 (0.034) | −0.020 (0.033) |

| SalesGrowth | −0.010** (0.004) | −0.011** (0.005) | −0.008* (0.005) |

| Advertising | −0.198 (0.179) | −0.377** (0.182) | 0.018 (0.02) |

| Capital | −0.016 (0.045) | 0.027 (0.058) | −0.059 (0.050) |

| RD | 0.124 (0.215) | 0.091 (0.249) | 0.156 (0.210) |

| Nmarket | −0.006 (0.007) | 0.004 (0.009) | −0.016** (0.008) |

| Institution | −0.011 (0.007) | −0.010 (0.008) | −0.013 (0.009) |

| Analyst | 0.001*** (0.001) | 0.001** (0.001) | 0.002*** (0.001) |

| Big4Auditor | −0.001 (0.006) | 0.003 (0.007) | −0.004 (0.007) |

| InvPro | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.009 (0.018) | −0.004 (0.007) |

| RegQual | −0.012 (0.009) | −0.030*** (0.011) | −0.020 (0.021) |

| GDP | −0.025 (0.023) | −0.014 (0.025) | 0.006 (0.010) |

| FDI | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001*** (0.001) |

| RuleLaw | 0.080** (0.034) | 0.096*** (0.036) | −0.064 (0.040) |

| Constant | 0.340 (0.238) | 0.305 (0.259) | 0.373 (0.272) |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.225 | 0.176 | 0.182 |

- Note: This table presents the regression results for the effect of board reforms on CSR performance. The dependent variable in columns (1)–(3) is CSR_Perf, ENV_Perf, and SOC_Perf, respectively. Post is an indicator variable that equals to 1 for the year that corporate governance reform became effective in a country and afterward, and 0 otherwise. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All of the variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

A company's CSR performance can be manifested in many dimensions. To conduct an in-depth analysis, we further decompose each firm's CSR performance into five categories: environment, product, workforce, society, and customer. We use the performance score in each of the five categories as the dependent variable to estimate model 1. The regression results (untabulated) indicate significantly positive estimated coefficients for four of the five categories (only the customer category is not significant).20

5.2 Alternative DID specification

Our baseline results are obtained using a staggered DID research design. This design has a key advantage: it automatically takes all firms from countries without reforms at a given time as the benchmark group (i.e., including all pre-reform observations in the reform countries). However, the various benchmark groups in different years provide a less clear picture of the composition of the benchmark sample. To examine whether our findings are robust across different model specifications, we use an alternative DID design with two alternative benchmark groups: (1) the United Kingdom, the first country to implement corporate governance reforms after 1998, and (2) all countries with reforms implemented outside of the testing period, including the United Kingdom (referred to as non-reformed countries). In this specification, we create an indicator variable, Reform, which equals to 1 for the treatment firms and 0 for the benchmark firms. For the benchmark group (either the United Kingdom or all non-reformed countries), because no reform has been implemented (i.e., all years are non-reform years), we set 2004 as the pseudo reform year for the definition of Post.21 By using this research design, we can more directly compare the change in firms' CSR in the treatment countries in the post-reform period relative to the pre-reform period with the change in firms' CSR in the benchmark countries during the same period.

Column (1) of Table 4 uses all firms in non-reformed countries as benchmark firms. We find that the coefficient on the interaction Reform × Post is positive (coefficient = 0.032) and significant (p < .05). As shown in column (3), we find similar results when we use only firms in the United Kingdom as benchmark firms. Next, we use the propensity score matching (PSM) approach to identify more comparable benchmark firms from non-reformed countries.22 Columns (2) and (4) of Table 4 report the multivariate regression results using propensity score matched firms from non-reformed countries and from the United Kingdom, respectively, as the benchmark. The results in both columns support the prediction of a positive effect of reform on firms' CSR rating.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark country | Non-reformed countries as benchmark | United Kingdom as benchmark | ||

| Full sample | PSM sample | Full sample | PSM sample | |

| Dependent variable | CSR_Perf | CSR_Perf | CSR_Perf | CSR_Perf |

| Post | −0.015 (0.012) | −0.027 (0.017) | −0.052*** (0.016) | −0.077*** (0.029) |

| Reform × Post | 0.032** (0.014) | 0.037** (0.017) | 0.063*** (0.017) | 0.082*** (0.030) |

| Size | 0.024*** (0.007) | 0.021*** (0.008) | 0.025*** (0.008) | 0.018** (0.009) |

| Age | 0.030 (0.021) | 0.034 (0.024) | 0.021 (0.022) | 0.028 (0.024) |

| Leverage | −0.039 (0.030) | −0.031 (0.035) | −0.019 (0.033) | −0.019 (0.036) |

| Accrual | −0.006 (0.010) | −0.005 (0.012) | −0.004 (0.012) | −0.001 (0.013) |

| MB | 0.001* (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Competition | −0.017 (0.028) | −0.025 (0.035) | −0.034 (0.026) | −0.040 (0.038) |

| Cash | −0.011 (0.031) | −0.001 (0.037) | −0.004 (0.034) | −0.002 (0.038) |

| SalesGrowth | −0.010** (0.004) | −0.006 (0.005) | −0.010* (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) |

| Advertising | −0.193 (0.179) | −0.178 (0.247) | −0.146 (0.237) | −0.049 (0.247) |

| Capital | −0.013 (0.045) | −0.017 (0.050) | 0.025 (0.053) | −0.006 (0.052) |

| RD | 0.127 (0.215) | 0.225 (0.291) | 0.127 (0.304) | 0.215 (0.318) |

| Nmarket | −0.006 (0.007) | −0.014* (0.008) | −0.015* (0.008) | −0.016* (0.009) |

| Institution | −0.009 (0.007) | −0.008 (0.008) | 0.001 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.008) |

| Analyst | 0.001*** (0.001) | 0.001** (0.001) | 0.001** (0.001) | 0.001** (0.001) |

| Big4Auditor | 0.001 (0.006) | 0.002 (0.009) | 0.011 (0.010) | 0.008 (0.011) |

| InvPro | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.017 (0.021) | −0.016 (0.022) | −0.015 (0.023) |

| RegQual | −0.009 (0.009) | −0.014 (0.010) | −0.014 (0.010) | −0.017 (0.011) |

| GDP | −0.027 (0.023) | −0.028 (0.033) | −0.010 (0.034) | −0.028 (0.038) |

| FDI | 0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) |

| RuleLaw | 0.075** (0.034) | 0.028 (0.051) | 0.042 (0.047) | 0.011 (0.059) |

| Constant | 0.349 (0.239) | 0.453 (0.323) | 0.315 (0.311) | 0.522 (0.358) |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 14,443 | 14,646 | 12,676 |

| R2 | 0.225 | 0.245 | 0.241 | 0.251 |

- Note: This table presents the regression results for the effect of board reform on CSR performance using an alternative DID design. In columns (2) and (4), we match firms in the treatment group with firms in the benchmark group using PSM. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

5.3 Other robustness checks

We perform several other tests to ensure the robustness of our findings. First, we conduct multivariate regression tests using the constant sample rather than the full sample. This approach ensures that we are comparing the same set of firms across two periods (i.e., the pre- and post-reform periods). The untabulated results show a positive and significant coefficient on Post (0.023, significant at p < .01). Second, we compare the changes in CSR rating across two constant test windows (i.e., 1 year before and 1 year after reform). Although the sample size is much smaller due to a shorter window, this approach helps mitigate the potential concerns regarding possible confounding events, which are likely to be observed during a longer window that may also drive a change in firms' CSR rating. The estimated coefficient on Post is still significant and positive (0.041, significant at p < .01). Third, we exclude all firms from the United States (i.e., the country with the highest number of observations in the treatment group), and we find results consistent with our main inference (0.016, significant at p < .05).23 Fourth, to further alleviate the concern regarding unequal sample sizes across countries, we use a weighted least squares (WLS) model with the number of firm–year observations per country as the weighting factor. The result of this test does not change our inferences drawn from previous tests (0.085, significant at p < .01). Fifth, given the positive correlation between firm-level corporate governance and CSR documented in prior studies (Ferrell et al., 2016; Harjoto & Jo, 2011; Jamali et al., 2008; Jo & Harjoto, 2012), we include firms' corporate governance performance score (CG_Perf) obtained from ASSET4 as an additional control variable when testing model 1, and we continue to find consistent results.24 Finally, Lins et al. (2017) suggest that firms may have stronger incentives to engage in CSR activities during a period of financial crisis. Therefore, we conduct a robustness test by excluding observations in the financial crisis year (2008), and we find that our result still holds.

5.4 Tests of the parallel trend assumption and the dynamic effect of board reforms

The validity of the DID method depends crucially on the parallel trend assumption. That is, in assessing the possible changes in the CSR rating during the post-reform period, we assume that the trends in the outcome variables for the treatment and control groups during the pre-reform period are similar. To examine this assumption, we add into model 1 an indicator Postt − 1 capturing the year before the reform, Post_0 indicating the reform year, and the two interaction terms Reform × Postt − 1 and Reform × Post_0 (e.g., Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2003). The regression results presented in Table 5 indicate that the coefficients on these interaction terms are both insignificant, providing evidence that the parallel trend assumption holds. Moreover, we use a dynamic DID research design by decomposing the post-reform period into the first year (Post_1), second year (Post_2), and third and all subsequent years (Post_3 and above) after reforms. Across all CSR measures, we find that increases in CSR rating are evident from the second year after a country's implementation of reforms and that the positive effect of reforms on CSR appears to persist for a long horizon.

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) ENV_Perf | (3) SOC_Perf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postt – 1 | −0.049*** (0.016) | −0.047** (0.018) | −0.052*** (0.018) |

| Post_0 | −0.032 (0.020) | −0.038* (0.023) | −0.026 (0.023) |

| Post_1 | −0.040* (0.024) | −0.043 (0.028) | −0.038 (0.027) |

| Post_2 | −0.078*** (0.026) | −0.076** (0.031) | −0.080** (0.029) |

| Post_3 and above | −0.067** (0.028) | −0.069** (0.034) | −0.066* (0.031) |

| Reform × Post t − 1 | 0.019 (0.015) | 0.006 (0.018) | 0.031* (0.018) |

| Reform × Post_0 | 0.009 (0.016) | 0.013 (0.019) | 0.004 (0.020) |

| Reform × Post_1 | 0.018 (0.017) | 0.021 (0.020) | 0.015 (0.020) |

| Reform × Post_2 | 0.055*** (0.018) | 0.060*** (0.020) | 0.050** (0.021) |

| Reform × Post_3 and above | 0.050** (0.019) | 0.062** (0.022) | 0.038* (0.023) |

| Constant | 0.345 (0.247) | 0.358 (0.270) | 0.332 (0.278) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.229 | 0.181 | 0.184 |

- Note: This table presents the regression results for the effect of board reforms on CSR performance by using dynamic DID design. Postt − 1 indicates the year before reform. Post_0 indicates the year of the reform. Post_1 indicates the first year after reform; Post_2 indicates the second year after reform; and Post_3 and above indicates the third and all subsequent years after reforms. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All other variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

5.5 Placebo tests

To further assess the validity of the DID method, we conduct placebo tests using different pseudo reform years for countries without implemented reforms during our sample period. We find no evidence of changes in CSR rating subsequent to pseudo reform years.

5.6 Year-by-year examination

In this section, we use a year-by-year DID specification for the constant sample to test the robustness of our findings. In our sample, most of the major board reforms implemented by countries are distributed over the 2003–2006 period.25 As the United Kingdom implemented the earliest reform, we use it as the benchmark country in this test. We then assign a pseudo reform year to all of the firms in the benchmark country based on the actual reform year of the treatment countries. This specification allows us to test the changes in firms' CSR rating for the treatment firms relative to the changes in CSR rating for the control firms during the same pre- and post-reform years.26 We repeat this test for each year for the 2003–2006 period. The results (untabulated) clearly indicate that for most of the years (three out of four) with major reforms implemented, we observe higher CSR ratings after the implementation of reforms.

5.7 Using first reform

Some countries in our sample have more than one reform (see Appendix B for the list of countries); thus, in this section, we conduct a robustness test using the earliest identified board reform (first reform) as an alternate reform year. Panel A of Table 6 shows that the coefficient on Post (which is defined based on the year of the first reform) is consistently negative across all CSR performance measures. We find similar results in Panel B where we use the alternative DID specification. Overall, our inferences do not change regardless of the definition of the reform year.

| Panel A. Baseline results |

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) ENV_Perf | (3) SOC_Perf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post | 0.037*** (0.011) | 0.039*** (0.012) | 0.035*** (0.013) |

| Constant | 0.268 (0.236) | 0.216 (0.257) | 0.320 (0.273) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.177 | 0.182 |

| Panel B. Alternative DID specification | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark country | Non-reformed countries as benchmark | United Kingdom as benchmark | ||

| Full sample | PSM sample | Full sample | PSM sample | |

| Dependent variable | CSR_Perf | CSR_Perf | CSR_Perf | CSR_Perf |

| Post | −0.021* (0.012) | −0.023* (0.012) | −0.043*** (0.014) | −0.069*** (0.017) |

| Reform × Post | 0.046*** (0.014) | 0.047*** (0.015) | 0.062*** (0.016) | 0.094*** (0.021) |

| Constant | 0.287 (0.235) | 0.288 (0.261) | 0.149 (0.302) | 0.257 (0.428) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 19,722 | 14,646 | 8,000 |

| R2 | 0.227 | 0.227 | 0.243 | 0.251 |

- Note: This table presents the regression results using the earliest reform year. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

6 CROSS-SECTIONAL TESTS AND ADDITIONAL ANALYSES

6.1 Channel test

Our main results suggest that firms' CSR performance improves after the implementation of board reforms within the country. In this section, we explore the possible channels through which reforms could have a positive impact on CSR. Recent evidence suggests that integrating CSR performance criteria in executive compensation (referred to as CSR contracting) has become a prevalent practice in corporate governance (Flammer et al., 2019; Tsang, Wang, et al., 2020). Providing compensation incentives based on social and environmental performance can prevent executives from undertaking symbolic CSR activities and direct managers' attention toward CSR initiatives that create long-term value (Maas, 2018; Matějka et al., 2009). Therefore, we examine whether the improved CSR performance observed after board reforms results from the emerging practice of integrating CSR criteria in executive compensation.

Based on the data from ASSET4, we define the variable CSRContracting as an indicator equal to 1 if a firm's executive compensation is explicitly linked to CSR/sustainability/health and safety targets, and 0 otherwise. Then we regress CSRContracting on the indicator Post and control variables in model 1. The logistic regression results of this analysis are reported in Table 7. Column (1) of Table 7 shows that the coefficient on Post is positive and significant (0.493, significant at p < .05), suggesting that indeed firms are more likely to link executive compensation to CSR criteria after board reforms. To be consistent with the main analysis, we conduct robustness checks by excluding the United States (the largest treatment country) from our sample, and the results in column (2) also show a positive coefficient on Post (0.799, significant at p < .01). Given that CSR contracting has been found to have a positive effect on CSR performance (Flammer et al., 2019), our findings in Table 7 thus suggest that the incorporation of CSR criteria in executive compensation could be a mechanism through which board reforms improve CSR performance.27

| Sample | (1) Full sample | (2) Excluding the United States |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | CSRContracting | CSRContracting |

| Post | 0.493** (0.206) | 0.799*** (0.287) |

| Size | 0.115 (0.130) | 0.365** (0.173) |

| Age | −0.381 (0.378) | −0.828* (0.464) |

| Leverage | −1.039** (0.454) | −0.801 (0.676) |

| Accrual | −0.652* (0.391) | −0.529 (0.511) |

| MB | 0.006 (0.019) | −0.004 (0.033) |

| Competition | −0.341 (0.681) | −0.064 (0.714) |

| Cash | 0.114 (0.788) | 0.857 (1.076) |

| SalesGrowth | −0.133 (0.153) | −0.295 (0.196) |

| Advertising | 23.422*** (6.790) | 25.661** (12.694) |

| Capital | 0.706 (1.585) | 2.594 (2.062) |

| RD | −12.062*** (4.210) | −8.786 (7.263) |

| Nmarket | −0.366** (0.146) | 0.193 (0.196) |

| Institution | −0.065 (0.256) | −0.267 (0.377) |

| Analyst | 0.009 (0.008) | 0.017* (0.010) |

| Big4Auditor | 0.151 (0.245) | 0.027 (0.276) |

| InvPro | −0.643 (0.446) | −0.637 (0.477) |

| RegQual | 0.045 (0.219) | −0.886*** (0.288) |

| GDP | 3.019*** (0.602) | 3.848*** (0.850) |

| FDI | −0.006 (0.009) | −0.018* (0.011) |

| RuleLaw | 1.807* (0.968) | 1.973* (1.140) |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 6,143 | 3,515 |

| R2 | 0.357 | 0.248 |

- Note: This table presents the logistic regression results for the effect of board reforms on CSR contracting. CSRContracting is an indicator equal to 1 if a firm's executive compensation is linked to CSR/sustainability/health and safety targets, and 0 otherwise. Post is an indicator variable that equals to 1 for the year that corporate governance reform became effective in a country and afterward, and 0 otherwise. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All other variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

6.2 Different objectives/types of board reforms

Next, we examine whether reforms with different objectives (i.e., promoting board independence, encouraging audit committee and auditor independence, and separating the chairman and CEO positions) affect CSR rating differently. The literature suggests that all of these mechanisms are associated with higher levels of board monitoring.28 Because countries differ in their objectives/types of reforms, we repeat our analysis after restricting the sample to countries implementing each type of reform (see Appendix B for a list of countries with each type of reform). In Panel A of Table 8, we continue to observe a positive relationship between CSR and board reforms covering board independence as well as audit committee and auditor independence. The results are robust based on either major reform or first reform. Panel B of Table 8 reports the results of the analysis controlling for the effect of concurrent non-board governance reforms. We perform this analysis by adding a dummy variable, Post_NonBoard, which indicates periods subsequent to the reforms with additional non-board components. We find no evidence that reforms involving non-board components have incremental effects beyond those involving board characteristics. More importantly, after controlling for the effect of non-board components, we continue to find a significantly positive association between board reforms and CSR performance.

| Panel A. Analysis of board reform components |

| Board independence | Audit committee and auditor independence | Chairman and CEO separation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) Major reform | (2) First reform | (3) Major reform | (4) First reform | (5) Major reform | (6) First reform |

| Post | 0.026*** (0.010) | 0.035*** (0.012) | 0.031*** (0.011) | 0.039*** (0.012) | 0.001 (0.014) | 0.001 (0.019) |

| Constant | 0.161 (0.275) | 0.102 (0.276) | 0.265 (0.270) | 0.164 (0.267) | −0.814** (0.338) | −0.816** (0.344) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.237 | 0.237 | 0.178 | 0.179 | 0.147 | 0.147 |

| Panel B. Controlling for non-board components | ||||||

| Variable | (1) Major reform | (2) First reform | ||||

| Post | 0.025** (0.010) | 0.033** (0.013) | ||||

| Post_NonBoard | 0.004 (0.010) | 0.007 (0.013) | ||||

| Constant | 0.327*** (0.123) | 0.277 (0.235) | ||||

| Control variables | Included | Included | ||||

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | ||||

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | ||||

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.226 | ||||

- Note: This table reports the analysis of major components of board reforms on CSR performance. Panel A focuses on the analysis of major board reform components. The dependent variable is CSR performance. Post is an indicator variable that equals to 1 for the year that corporate governance reform became effective in a country and afterward, and 0 otherwise. Panel B presents the effect of non-board components on CSR performance. Post_NonBoard is an indicator variable indicating periods subsequent to the reforms with additional non-board components. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All of the other variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

6.3 Different approaches to corporate governance reforms

We also examine whether the effect of reforms varies across comply-or-explain or rule-based reforms. Although both reform approaches are prevalent, there are conflicting views regarding which is more effective. Some argue that the one-size-fits-all rule-based approach runs the risk of overregulation, while others opine that the comply-or-explain approach might not yield the intended effect. To test the moderating effects of these reform approaches, we use an indicator variable, Rule, to identify countries with rule-based reform, and we interact this variable with Post.29 Thus, the interaction term Post × Rule captures the difference (if any) in the effect of rule-based reforms relative to comply-or-explain-based reforms on CSR rating. The results (Table 9) suggest that the effect of reforms on CSR is stronger when the reform uses a rule-based approach.

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) ENV_Perf | (3) SOC_Perf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post | −0.002 (0.012) | −0.007 (0.014) | −0.012 (0.014) |

| Post × Rule | 0.051*** (0.017) | 0.044** (0.018) | 0.058*** (0.020) |

| Constant | 0.125 (0.226) | 0.119 (0.243) | 0.129 (0.265) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.227 | 0.177 | 0.183 |

- Note: This table reports the cross-sectional variation of board reforms on CSR performance based on a country's reform approach. Rule is an indicator that equals to 1 if a country adopts a rule-based reform approach and 0 if a country adopts a comply-or-explain reform approach. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All other variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

6.4 The moderating effect of CSR awareness

The literature suggests that the effectiveness of corporate governance mechanisms could be conditional on country-level institutions. For instance, Dahya et al. (2008) find that board independence, a major element of corporate governance, is positively related to firm value in countries with poor investor protection, but they do not find a significant relationship in countries with strong investor protection. Regarding CSR performance, prior studies suggest that the value of CSR initiatives is greater in stakeholder-oriented countries that place greater emphasis on CSR activities (Dhaliwal et al., 2012; Simnett et al., 2009; van der Laan Smith et al., 2010). Therefore, we expect to observe a stronger positive effect of reforms on CSR rating when investors have a higher level of CSR awareness. However, in countries where the level of CSR awareness is high, it is also likely that further improvement of CSR initiatives tends to be more costly given the high level of CSR performance already observed in the pre-reform period.30 This prediction suggests a weaker effect of reforms on CSR in countries with high levels of CSR awareness.

To examine whether and how country-level CSR awareness affects the relationship between reforms and CSR, we interact Post with an indicator variable, HI_Pubaware, which captures the level of public awareness of CSR issues in individual countries (Dhaliwal et al., 2012).31 The results reported in Panel A of Table 10 show a negative and significant coefficient on the interaction term Post × HI_Pubaware. These findings suggest a relatively weaker effect of reforms on CSR in countries with high levels of CSR awareness. This finding also raises the concern that firms with lower levels of CSR investment have gradually succumbed to global pressure to improve their CSR initiatives over time, which might explain our finding of a positive effect of reforms on CSR. Thus, in an additional test, we create a matched sample in which treatment and control firms are matched based on their CSR investment prior to the regulatory reforms to rule out the possible alternative explanation. Finally, we also directly control for firms' prior CSR performance in our regression. Our results (untabulated) are qualitatively similar in all these tests.

| Panel A. CSR awareness, board reform, and CSR performance |

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) ENV_Perf | (3) SOC_Perf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post | 0.068*** (0.013) | 0.074*** (0.014) | 0.063*** (0.015) |

| Post × HI_Pubaware | −0.074*** (0.016) | −0.081*** (0.018) | −0.067*** (0.019) |

| Constant | 0.091 (0.095) | 0.083 (0.117) | 0.100 (0.095) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Clustered by country | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.230 | 0.181 | 0.184 |

| Panel B. Stringency of legal environment, board reform, and CSR performance | |||

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) CSR_Perf | (3) CSR_Perf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post | −0.005 (0.012) | −0.009 (0.013) | −0.009 (0.013) |

| Post × HI_InvPro | 0.070*** (0.016) | 0.039* (0.022) | |

| Post × HI_RegQual | 0.068*** (0.016) | 0.034* (0.021) | |

| Constant | 0.124 (0.096) | 0.128 (0.096) | 0.127 (0.095) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Clustered by country | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.229 | 0.229 | 0.230 |

| Panel C. Ownership, board reform, and CSR performance | |||

| Dependent variable | (1) CSR_Perf | (2) CSR_Perf |

|---|---|---|

| Post | 0.011 (0.010) | 0.025*** (0.009) |

| Post × HI_Institution | 0.019*** (0.005) | |

| Post × HI_Insider | −0.017** (0.008) | |

| Constant | 0.108 (0.097) | 0.106 (0.098) |

| Control variables | Included | Included |

| Fixed effects | Included | Included |

| Clustered by country | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 20,293 | 20,293 |

| R2 | 0.227 | 0.226 |

- Note: This table reports the results examining whether the effect of board reforms on CSR performance varies with country- and firm-level characteristics. Firm-, year-, and industry-fixed effects are included in all the tests. All other variables are defined in Appendix A. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Bold indicate that these are the variables of interest.

- *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

6.5 The moderating effect of the legal and regulatory environment

In this section, we examine whether the positive association between reforms and CSR varies with the stringency of a country's legal and regulatory environment. It is well documented in the literature that capital market consequences possibly associated with the implementation of rules or the adoption of a mandatory requirement in a country depend strongly on the country-level institutional factors related to legal and regulatory environment. For instance, Brown et al. (2014) show that the effectiveness of accounting regulation is more pronounced in countries with stronger enforcement. Christensen et al. (2013) also find that the capital market effects associated with the mandatory adoption of IFRS largely are driven by a small number of IFRS-adopting countries with enhanced country-level enforcement. Country-level institutions related to legal and regulatory environment do not only influence the effect of mandatory requirements (such as the adoption of board reforms in a country); it can also impact the effect of voluntary decisions made by the firms (such as the CSR investment decision made by managers). For example, Cao et al. (2017) find that voluntary financial reporting tends to have a stronger effect on the cost of equity capital in countries with stronger investor protection. Following the findings of these studies, we believe it is reasonable to expect that the effect of board reforms on CSR would be stronger in countries with stronger institutions related to legal and regulatory environment.32

We add the interaction terms Post × HI_InvPro and Post × HI_RegQual in model 1 to estimate the regression. Table 10, Panel B, shows a positive and significant coefficient on Post × HI_InvPro, suggesting that the effect of reforms is stronger in countries with higher levels of investor protection. We consistently find a significant and positive coefficient on Post × HI_RegQual, which again supports the prediction that the positive effect of reforms on CSR is more pronounced in countries with a more stringent regulatory environment. In the last column, where we include both interaction terms in the same model, we continue to find positive and significant coefficients on both interaction terms. Collectively, the results support the argument that reforms cannot exert a positive influence unless accompanied by strong legal enforcement.33

6.6 The moderating effect of ownership

Using an international setting, Dyck et al. (2019) present evidence that institutional ownership is positively associated with firms' CSR performance. They further show that the positive effect of institutional ownership on firms' CSR performance is motivated by both financial and social returns as perceived by institutional investors. Other studies suggest that firms with more concentrated insider ownership are likely to observe a greater level of conflict of interest between controlling insiders and external shareholders (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2003; Koirala et al., 2020; Stulz, 2005). We examine whether and how institutional and insider ownership (a contrasting measure to institutional ownership) moderates the effect of reforms on firms' CSR.

Table 10, Panel C, indicates that when we interact Post with HI_Institution (an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm's institutional ownership is greater than the median institutional ownership of all firms in the same industry, and 0 otherwise), we find a positive and significant coefficient on the interaction term Post × HI_Institution. This finding is consistent with institutional investors putting more pressure on firms to engage in more CSR activities. Next, we interact Post with HI_Insider, an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm's CEO ownership is greater than the median CEO ownership of all firms in the same industry, and 0 otherwise. The results show a significant and negative coefficient on Post × HI_Insider, indicating a weakened effect of reforms on CSR when firms' insider ownership is high. Consistent with previous studies, our findings suggest that the presence of agency conflict reduces managers' incentives for CSR investment.

6.7 Board reform, CSR, and future financial performance

While our main findings suggest that better corporate governance encourages firms to engage in more CSR activities, they do not indicate that CSR investment is perceived favorably by investors. Managers might expropriate corporate resources for self-interest or to cover up personal misconduct (Barnea & Rubin, 2010; Masulis & Reza, 2015; Prior et al., 2008); thus, CSR investment may not always have a positive effect on firm performance (Barnett & Salomon, 2006; McWilliams & Siegel, 2000; Orlitzky et al., 2003). Because the implementation of board reforms should strengthen the board's oversight function and reduce the agency problem, managers are expected to make better CSR investment after governance reforms to ensure proper returns to shareholders. Supporting this view, agency theorists argue that corporate governance should be designed to promote CSR initiatives only when CSR activities lead to significant benefits (Jain & Jamali, 2016; McWilliams & Siegel, 2001). This view is consistent with the conflict resolution hypothesis proposed in prior studies (e.g., Jo & Harjoto, 2012, p. 57). According to this hypothesis, if corporate governance mechanisms and CSR engagement effectively resolve conflicts between various stakeholders, firm value is expected to be positively related to both the effective governance mechanism and CSR engagement. Accordingly, in this section, we further examine whether CSR investment and firms' future financial performance are more positively correlated in countries with reforms.