The impact of renter protection policies on rental housing discrimination

This RCT was registered as AEARCT-5240 (Gorsuch & Rho, 2020).

Abstract

We examine the impact of a policy that reduces information about rental housing applicants on racial discrimination. We submitted fictitious email inquiries to publicly advertised rentals using names manipulated on perceived race and ethnicity before and after a policy that restricted the use of background checks, eviction history, income minimums, and credit history in rental housing applications in Minneapolis. After the policy was implemented, discrimination against African American and Somali American men increased. Triple difference analysis shows that discrimination increased in Minneapolis relative to St. Paul after the policy.

Abbreviations

-

- AEA

-

- American Economic Association

-

- CDC

-

- Center for Disease Control

-

- IPUMS ACS

-

- Integrated Public Use Microdata Series American Community Survey

-

- MNSDC

-

- Minnesota State Demographic Center

-

- RA

-

- research assistant

-

- RCT

-

- randomized control trial

-

- SES

-

- socioeconomic status

1 INTRODUCTION

People of color, immigrants, and individuals with a criminal record face well-documented and significant discrimination in housing (Baldini & Federici, 2011; Bosch et al., 2010, 2015; Hanson & Santas, 2014; Hogan & Berry, 2011; Roman & Travis, 2004; Turner et al., 2013). Discrimination in housing has adverse effects on wellbeing, including limited employment opportunities (Boeri et al., 2015; Phillips, 2018), poor health outcomes (LaVeist, 2003), racial and ethnic segregation (Bosch et al., 2015), and increased recidivism (Fontaine & Biess, 2012).

Bergman et al. (2024) find that barriers in the housing search process are a major factor in residential segregation by income. Other work finds that landlords avoid tenants who are seeking to pay by voucher and this penalty increases with monthly rent (Aliprantis et al., 2022; Phillips, 2017). In the short-term rental market, Edelman et al. (2017) find evidence of discrimination against Airbnb hosts with distinctively African American names. In an effort to increase access to housing for lower-income workers, people of color, and formerly incarcerated people, numerous cities in the United States have passed, or are considering passing, renter protection policies that restrict the use of background checks, eviction history, strict income minimums, and credit history in the rental housing application process (Racial Equity Alliance, 2017). Despite the increasing popularity of policies that restrict the use of screening mechanisms in the rental housing market, there is little to no research on the impact of these policies.

Previous research has found that similar policies have mixed results in the labor market. For example, restricting the use of pre-employment credit checks appears to reduce a Black job seeker's match with a job (Bartik & Nelson, 2025). Likewise, policies that limit the use of background checks early in the employment application process have sometimes been found to increase discrimination against young Black and Latino men (Agan & Starr, 2017; Doleac & Hansen, 2020). Policies that increase information about job seekers can improve outcomes; for example, legislation that allows drug testing increases Black employment (Wozniak, 2015).

However, other studies find that policies that restrict the use of criminal history in the job application process reduce discrimination against formerly incarcerated people (Agan & Starr, 2018) particularly in the public sector (Craigie, 2019; Shoag & Veuger, 2021). Similarly, expungement of criminal records also improves employment outcomes, especially for Black applicants (Prescott & Starr, 2020).

The rental housing market shares key similarities with the labor market. In both markets, a decision maker is choosing among multiple candidates but has incomplete information about each applicant. Because of this incomplete information, both employers and landlords often use screening mechanisms to help select among the candidates. Yet, little is known about the impact of policies restricting the use of screening mechanisms in the rental housing market.

In this paper, we examine the impact of a policy that limits the use of some methods to screen rental applicants. We measure the change in rental housing discrimination against African American and Somali American applicants after Minneapolis implemented a policy that limits the use of background checks, eviction history, and credit score. We additionally examine if the new policy had a different impact on male applicants and in Census tracts with higher reported crimes per capita. Minneapolis' “twin city” of St. Paul passed a nearly identical policy that went into effect 9 months after the Minneapolis policy.

To investigate the impact of these policies, we implemented a correspondence study where we submitted fictitious email inquiries to publicly advertised rental units using names that are manipulated on perceived race and ethnicity (Somali American, African American, and white American) and gender. We began data collection prior to the implementation of the policy and continued after the policy took effect. We first examine the change in discrimination in Minneapolis (where the policy was implemented) and then compare the change in Minneapolis to the change in neighboring St. Paul (where a similar policy was implemented at a later date). This approach identifies the impact of the new policy on rental housing discrimination. Additionally, because previous work finds that Black and Arab men experience higher levels of discrimination in the housing market, we stratify our analysis by gender to examine the impacts of the policy on inquiries from men and women.1

To examine if the experience of housing seekers varies by neighborhood, we investigate whether the impact of the policy varied by local reported crime rates. We test whether the impact of the new policy is different in neighborhoods with more reported crimes per capita.

We find evidence that the new policy worsened discrimination against Somali American and African American rental applicants. After implementing a policy that restricts the use of background checks, credit history, and eviction history, the difference in positive responses to African American and Somali American applicants compared to white American applicants in Minneapolis increased by over 15% points for both groups. This increase was largest for units that were two or more bedrooms and among emails sent from male names. We find that the largest increase in discrimination occurred in Census tracts with more reported crimes per capita. We then use St. Paul as a counterfactual to account for secular changes in the housing market and implement a triple-difference analysis. We find that the policy in Minneapolis was associated with a large increase in discrimination against Somali American and African American rental applicants relative to St. Paul.

Because we are comparing changes in Minneapolis relative to St. Paul, events that occurred in Minneapolis at the same time as the implementation of the policy could be driving our results. There are two potential threats to identification: the protests following George Floyd's murder by the Minneapolis Police Department and the COVID-19 pandemic. We find similar results when we leave out south Minneapolis, where most property damage was located, suggesting that the protests were not driving our results. COVID-19 had similar impacts in both cities so the triple difference analysis accounts for any broad changes like those related to COVID-19, such as restrictions on certain businesses or the statewide eviction moratorium. Additionally, we test if changes in data collection due to COVID-19 could have impacted our results and find no evidence of this.

1.1 Why applicant protection policies may inadvertently impact discrimination

Black and Latino individuals have lower average income (Chetty et al., 2020), lower average credit scores (Leonhardt, 2021), higher incarceration rates (Raphael, 2014), and higher rates of eviction (Hepburn et al., 2020) than other groups due to upstream barriers or bias in education, the labor market, and the criminal justice system. It is intuitive that a policy that removes information on income, credit score, and criminal history in employment or housing applications would benefit Black and Latino applicants. When Minneapolis passed a broad set of renter protections, City Council Member Jeremiah Ellison stated, “The intention of the [renter protection] ordinance is to reduce unnecessary financial and screening barriers that block people who are ready to enter the rental housing market from doing so” (Desmond, 2019).

However, previous research has found that policies that reduce information on applicants have mixed results in the labor market, particularly for Black men. At the center of the controversy are policies that restrict employers from asking about criminal history on initial job applications. Agan and Starr (2018) raised concerns about potential unintended consequences of these polices. They submitted fictitious resumes to employers before and after the implementation of a policy limiting background checks in initial employment applications. Prior to the policy, there was a 7% gap between employers contacting resumes that appeared to be from young white men and those that appeared to be from young African American men; this increased to 43% after ban the box was implemented. Similarly, Doleac and Hansen (2020) found that ban the box policies increased discrimination against young Black men. They argue that the increase in discrimination may result from “statistical discrimination”—where employers are making decisions based on their belief about a group's probability of having a criminal record when information on the individual applicant's criminal record is not available.

This finding is not universal—for example, Burton and Wasser (2024) note that the Doleac and Hansen (2020) findings are sensitive to the model specification. Craigie (2019) and Shoag and Veuger (2021) found that ban the box policies benefited formerly incarcerated people seeking jobs in the public sector and found little evidence of increased discrimination. Rose (2021) finds negligible impacts of restricting the use of criminal history in the early stages of the hiring process on the labor market outcomes of ex-offenders; however, expungement of criminal records has been found to improve employment outcomes for those with criminal records, especially for Black individuals (Prescott & Starr, 2020).

While a great deal of recent research has focused on policies limiting the use of criminal history, policies intended to protect applicants in the labor market are much broader. For example, restricting the use of pre-employment credit checks reduces a Black job seeker's match with a job (Bartik & Nelson, 2025), and legislation that allows drug testing increases Black employment (Wozniak, 2015). The observed increase in discrimination in the labor market after the implementation of policies that reduce potential negative information about applicants suggests that when an applicant's individual information is not available, employers may make decisions based on the perceived group average—increasing discrimination based on race and ethnicity.

Much of the research on the unintended consequences of policies that attempt to protect marginalized applicants has focused on the labor market. However, similar policies are becoming increasingly popular in the housing market. It remains unclear if the findings from the labor market extend to the rental housing market. In some ways the two markets function similarly—in both contexts, decision makers have incomplete information and are selecting among multiple applicants. However, there are also important differences. Employers may be seeking the applicant who will be the most productive, whereas landlords may be searching for someone who is above a certain bar (e.g., will pay rent and will not harm the property). Bartoš et al. (2016) shows that employers spend less time evaluating applications from marginalized groups whereas landlords spend more time on these applications. It is not clear if a policy that attempts to protect applicants by removing information will function the same way in the housing market as it does in the labor market. In this paper, we directly address this gap by evaluating the impact of a set of renter protections on racial discrimination in the rental housing market.

1.2 Heterogeneity by neighborhood and unit type

Discrimination in rental housing varies by neighborhood demographics, regional characteristics, housing unit characteristics, and landlord characteristics (Carlsson & Eriksson, 2014; Christensen & Timmins, 2023; Ewens et al., 2014; Hanson & Hawley, 2011). Christensen and Timmins (2023) implemented a large audit study across the U.S. and finds that property managers discriminated more against Black and Latinx rental applicants for higher rent units and in neighborhoods with higher school quality, lower air pollution, higher percent white, and more rental demand. Phillips (2017) similarly finds that discrimination against tenants wishing to pay using a voucher increases as the monthly rent increases. Evidence is more mixed on the impact of the type of housing; Hanson and Santas (2014) finds more discrimination against Latinx applicants for single family homes while Hanson and Hawley (2011) finds more discrimination against Black applicants for apartments and condos.

Neighborhood-level characteristics matter as well: Agan and Starr (2024) find that employers in neighborhoods with fewer Black residents appear more likely to stereotype Black applicants as having a criminal record when they do not have information on specific applicants. Similarly, landlords in neighborhoods near racial “tipping points” show more discrimination (Hanson & Hawley, 2011).

Because the new renter protection included restricting the use of screening based on some criminal records, landlords in areas with more reported crime may respond more strongly to the new policy. To examine this, we test whether the impact of the new policy is different in neighborhoods with more reported crimes per capita. We also examine if one-bedroom units, which are almost always in apartment complexes with on-site property managers, have different levels of discrimination than larger units, which are more often single-family homes and have higher average monthly rent.

2 POPULATION AND SETTING

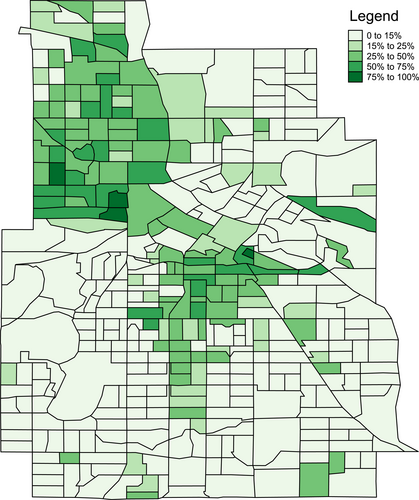

Minneapolis (population 425,403) and St. Paul (population 307,695) are consistently ranked among the cities with the highest racial disparities in income, education, and home ownership (Beaumont, 2020; Buchta, 2017; Furst & Webster, 2019). Like many Northern cities, Minneapolis and St. Paul have a long history of using racial covenants to restrict the sale of homes to people of color—a pattern termed the “Jim Crow of the North” (PBS, 2019). While these racial covenants were banned by the Minnesota Legislature in 1953 and by the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, their presence is palpable in the low homeownership rate among Black residents and highly segregated neighborhoods (Mapping Prejudice, 2020; Minnesota State Demographic Center, 2018; Sood et al., 2024). Figure 1 shows the estimated proportion of residents who identify as “Black or African American” in Minneapolis in 2014.

A map of Minneapolis showing the proportion reporting their race as “Black or African American” (2014 pooled 5 years ACS via American FactFinder). Figure from Gorzig and Rho (2022).

Minneapolis and St. Paul are home to the largest Somali American diaspora in the United States, allowing us to examine if rental housing discrimination and policies to reduce discrimination function differently for Black refugees and native-born African Americans. Beginning in the early 1990s, the U.S. began receiving refugees from the civil war in Somalia. Minnesota, and particularly the Twin Cities area, served as a major destination for refugees. Using IPUMS ACS data (Ruggles et al., 2015), we estimate that in 2015, over 35% of all people in America who identified as Somali lived in Minnesota. In 2015, approximately 24,256 Somali Americans lived in Minneapolis and St. Paul, comprising an estimated 3.4% of the Twin Cities population (Gorzig & Rho, 2022). Somali Americans comprise a large and important ethnic group within Minnesota, particularly the metropolitan area. Somali Americans have established neighborhoods south of downtown; the Riverside Plaza is a well-known apartment complex housing recent immigrants and is known as “Little Somalia.” However, overall foreign-born Black Americans are less segregated in Minneapolis than U.S.-born Black Americans (Crowell & Fossett, 2020).

2.1 Minneapolis Renter protection policy

In September 2019, the Minneapolis City Council passed a law restricting the use of background checks, eviction histories, and credit scores in rental housing applications; the new policy went into effect in June 2020 for landlords with more than 15 units (Evans, 2019). St. Paul, Minneapolis' “twin” city, passed a similar policy that went into effect on March 1, 2021. These laws bar landlords from considering misdemeanors that are older than 3 years and felonies older than 7 years. For certain felonies, landlords cannot consider convictions that are older than 10 years.

Additionally, landlords cannot legally consider evictions older than three or more years from the date of application. While landlords are permitted to consider information on a credit report that is relevant to an applicant's ability to pay, the use of credit score to screen applicants is prohibited. Landlords are also not legally permitted to strictly require monthly income three or more times the rent and security deposits are capped at 1 month's rent.

Some aspects of the policy are harder to enforce than others. For example, landlords are still able to conduct background checks; they are not legally permitted to consider most older convictions. Likewise, the landlord is allowed to view an applicant's credit report but is not legally permitted to screen on a specific credit score. However, neither the applicant nor city enforcement can easily observe what the landlord is considering after completing the background or credit check. Though enforcement of every aspect of the policy is unlikely, the policy's prohibitions on screening tenants based on older criminal history and specific credit scores make screening more difficult for the landlord—they are no longer legally able to state in an ad that they are using a credit score cutoff or that they will not rent to anyone with a conviction, which is a low-cost way to screen applicants. While the policy is not able to prevent screening on credit score or conviction history, it makes it more costly for the landlord to do so. In contrast, requiring a certain income or security deposit can easily be viewed by tenants and therefore violations are more easily reported.

3 DATA

To evaluate the impact of this set of policies, we sent email inquiries from fictitious applicants to real landlords in Minneapolis and St. Paul who posted vacancies for their rental units online. We manipulate the name in the email and email address to indicate the potential tenant's gender and race/ethnicity. We began data collection in January 2020—six months prior to the implementation of the new policy in Minneapolis. This analysis includes data collected until February 28, 2021, the day before the St. Paul policy went into effect. This timing allows us to analyze landlords' behavior before the policy went into effect in either city and test whether this changed when the policy went into effect in Minneapolis but was not yet in effect in St. Paul.

We track which applicants the landlords respond to positively (e.g., offers to show the property). This style of study is known as a “correspondence study” or an “audit study” and is a commonly used method to test discrimination in the labor market (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004) and the housing market (Ahmed et al., 2010; Andersson et al., 2012; Friedman et al., 2013). We pre-registered this experiment with the AEA RCT Registry (#5240).

We manipulate the name in the emails and email addresses to indicate the potential tenant's gender and whether the applicant is Somali American, African American, or white American. The names used in the experiment are the ones we used in Gorzig and Rho (2022), in which we conducted a labor market experiment in Minnesota. The Somali American names were selected from the CDC's list of popular Somali first names. The Somali American names we use are Aasha Waabberi, Fathia Hassan, Khalid Bahdoon, and Abdullah Abukar.2

The African American and white American names are racially distinct and were pre-tested to select names that clearly signal race and do not signal different socioeconomic status (Gaddis, 2015; Levitt & Dubner, 2005). In Gorzig and Rho (2022), we evaluated potential names using Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online labor market where people perform piece-rate tasks such as surveys. Participants were shown a selection of names in random order and were asked to rate how strongly they associated the name with five major racial groups and whether they associated the name with high or low socioeconomic status. Respondents associated names with race and socioeconomic status. The African American names that were higher SES were perceived as having lower SES than lower SES white American names. To reduce the role that perceived differences in SES plays, we used high SES African American names and low SES white American names. For the surnames, we used the highest percent white and the highest percent African American of the top 100 most common surnames on the 2000 Census. The African American names used are Imani Williams, Nia Jackson, Andre Robinson, and Jalen Harris. The white American names we used are Amber Sullivan, Amy Wood, Jacob Myers, and Lucas Peterson.

Each inquiry to landlords was from an email address which included the applicant's first and last names.3 The inquiries included a greeting, a statement about seeing the rental listing, a line expressing interest in the unit, and a closing. We use a Python program designed for correspondence studies that creates email texts with the name and other email elements randomized (Lahey & Beasley, 2009). None of the email components are repeated within a listing.4

To send an inquiry, the research assistants (RAs) identified housing ads on Craigslist that included enough information to identify the city in which the apartment was located. For each ad that met the eligibility criteria, the RAs sent the randomized emails to the landlord from fictitious applicants. The name used to respond to each ad was selected randomly by the Python program; importantly, the RAs did not select the names to use nor did they select a subset of ads within those determined to be eligible.

In the initial study design, three emails were sent to each landlord with a time lag between each email. However, in late March 2020, Minnesota declared a state of emergency and implemented a “stay-at-home” order and eviction moratorium in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Walz, 2020). Because of the stay-at-home order, landlords became suspicious when receiving three email inquiries.5 The stay-at-home order stayed in place until late May 2020. In July 2020, Minnesota implemented a statewide mask mandate and many activities returned to more typical levels. From April 2020 to August 2020, we sent only one inquiry per ad to reduce detection risk (Balfe et al., 2023). In August 2020, we increased to sending two inquiries per ad. We implemented all changes to our protocol simultaneously in the two cities. Inquiries were not sent to the same landlord a second time until at least 6 months passed; RAs used the company name, phone number, and the formatting of the ad to avoid repeated inquiries to the same landlord within the 6-month period.

The statewide eviction moratorium was in effect from March 2020 to June 2022 (Volunteer Lawyers Network, 2021). The eviction moratorium may increase the cost of a tenant who does not pay rent, because the landlord will not be able to evict the tenant except under certain extreme circumstances, such as endangering other tenants or damaging the property. Thus, any impact of the renter protection policy we find may be larger in this setting than in settings where landlords are more easily able to evict a tenant.

When applying to rental units with two or more bedrooms, the applicant mentioned that they were looking for a new home for their family while the reference to family was not included when applying to a one-bedroom unit.6 The RAs tracked the “callbacks”—identifying which landlord sent a positive email for a fictitious applicant. When a landlord responded positively, the RA responded saying that the fictitious tenant was no longer interested in the unit. The most common positive response was an invitation to set up a time to tour the unit. A request for more information from the landlord was not considered a positive response.

In order to link each rental unit to neighborhood characteristics, we used the Census Geocoder to identify the Census tract of the rental unit. We then constructed neighborhood level reported crime rates from the Minneapolis Police Department's data on each reported crime in 2020.7 This data includes the latitude and longitude of the reported crime, which we then mapped to its corresponding Census tract. We used the estimated population from the 2016–2020 American Community Survey 5-year data to compute the number of reported crimes per capita in each Census tract in Minneapolis. In supplemental analyses, we additionally use demographic data from the American Community Survey at the Census tract level. This data includes the percent of the Census tract that is Black or African American, the percent Somali American, and the percent foreign born.

The Minneapolis policy went into effect on June 1, 2020 for landlords with 15 or more rental units and went into effect later for those with fewer rental units.8 To examine the impact of the policy, we restrict the analysis to ads that are likely to have 15 or more units.9 We examined all ads that list a company name and over 95% of those we could identify have 15 or more rental units. Thus, we use the presence of a company name in the ad to infer that the landlord is likely to have 15 or more properties (hereafter referred to as “large companies”).10 Some landlords are not identifiable in the ads that are posted. We do not know when the policy went into effect for these units and therefore are not able to include them in the analysis of the impact of the policy. We sent 1429 emails to landlords in Minneapolis and St. Paul with 15 or more units, 944 before the policy and 485 after the policy. About 62% (879) of the inquiries were sent to Minneapolis listings and about 38% (550) were sent to listings in St. Paul.

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of the email inquiries sent to large companies, the characteristics of the housing ads, and responses from landlords. As expected, the email inquiries are balanced with respect to race/ethnicity and gender—the program created emails where 1/3 have white American names, 1/3 Somali American names, and 1/3 African American names.

Just under half the emails are from women's names and half from men's names. The order sent variable reflects the changes to the number of email inquiries sent to each landlord over the course of data collection; due to the stay-at-home order at the beginning of the pandemic, we sent three emails only for the initial portion of data collection. Fifty two percent of email inquiries for units in Minneapolis and 58% of email inquiries for units in St. Paul were sent to ads for two or more bedrooms. Reflecting Minneapolis' larger size, 62 percent of all emails were sent to ads for units in Minneapolis. The most common outcome is positive (42%) followed by no response (34%). A negative response to an email inquiry was very rare (2.3%).

| (1) Percentage or average | (2) Chi-squared test | (3) p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Email characteristics | |||

| Somali American | 32% | ||

| White American | 34% | ||

| African American | 34% | ||

| Female | 48% | 0.16 | 0.93 |

| Order sent | |||

| Sent first | 48% | 3.1 | 0.54 |

| Sent second | 31% | ||

| Sent third | 21% | ||

| Ad characteristics | |||

| Two or more bedrooms | 54% | 0.45 | 0.80 |

| Minneapolis | 62% | 0.55 | 0.76 |

| Monthly rent (average) | $1543.66 | ||

| Prohibits those with criminal record (n = 1427) | 11.2% | 0.59 | 0.75 |

| Prohibits previous evictions (n = 1427) | 13.7% | 1.07 | 0.59 |

| Requires income 3× rent (n = 1427) | 8.1% | 1.15 | 0.56 |

| Includes specific credit score (n = 1427) | 8.5% | 0.16 | 0.92 |

| Security deposit > rent (n = 1427) | 3.9% | 0.28 | 0.87 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Positive contact | 42% | 6.9 | 0.33 |

| Non-committal | 22% | ||

| No response | 34% | ||

| Negative | 2.3% | ||

- Note: Column (1) shows the percentage of the emails with each characteristic. Column (2) shows the chi-squared statistic for the test that the characteristic is distributed equally across the key manipulation (African American, Somali American, and white American). Column (3) shows the p-value for the chi-squared test in Column (2). n = 1429.

Columns 2 and 3 of Table 1 show the results of a chi-squared test that each characteristic is distributed equally across the race/ethnicity manipulation. We fail to reject that the characteristics are distributed equally (at the 5% level) for all the email and ad characteristics. Table A3 in Supporting Information S1 shows the descriptive statistics for large companies before and after the policy was implemented. Table A4 in Supporting Information S1 shows the same descriptive statistics for all emails and ads, not limited to those sent to large companies.

4 METHODS

4.1 Analysis: Did landlords change their behavior in response to the policy?

Prior to examining our main research question, we begin by investigating whether Minneapolis landlords adjusted their rental ads after the new law. It is relatively common for rental ads to use phrases like “clean background check” or “no felonies.” The new policy restricts the use of criminal background checks to only recent convictions, so these phrases violate the new policy. We had two RAs code the text in the rental ads in our data, both from before and after the policy, to indicate whether landlords included criteria that are prohibited by the new law. We examine five screening criteria banned by the new policy: requirement of income three times or higher than monthly rent, security deposit above 1 month rent, criminal background check that includes older convictions, specific credit score cutoff, and eviction history older than 3 years. The two RAs agreed on over 98% of ads coded for each of the five criteria. An ad is considered to include the criteria if one or both RAs indicated that it did.

If there is no change in the ad text, it is unlikely that the policy made an impact, and it is likely that something else is driving any resulting change in discrimination. On the other hand, a decrease in such language in the ads in Minneapolis after the policy would suggest that landlords are responding to the new law.

This analysis also serves to identify the mechanisms at work. The renter protection policy had multiple components, so examining the changes in various aspects of the ad texts gives insight into what parts of the policy had the most immediate impact on landlords' screening processes. Of course, this analysis will not capture all changes in landlord screening - we only observe the text in the ad, so any changes that occur later in the screening process will not be captured here.

4.2 Analysis: Estimating the impact of the new policy on discrimination

To examine our main research question, we evaluate whether housing discrimination changed after the implementation of the set of renter protections that restricted the use of background checks, eviction history, strict income minimums, and credit history in rental housing applications. We examine whether landlords' response rates to these applicants differ by perceived race of the potential tenants. While any individual applicant may be a better fit (email came first, landlord preferred the email text, etc.) than another individual applicant, on average all applicants are constructed to be equivalent - any differences in average response rates across perceived race can be interpreted as discrimination. We test whether discrimination changes due to the implementation of the new policy. If discrimination in Minneapolis changes after the policy goes into effect, while there are no changes (or smaller changes) in St. Paul, the difference in the change in discrimination is the impact of the new policy. By tracking discrimination in areas unaffected by the policy, we can account for any broader changes in discrimination that are occurring separately from the new policy.

The outcome variable is an indicator variable indicating if the landlord (l) made positive contact with the fictitious applicant (i). Coefficients and indicate the “baseline” level of discrimination in Minneapolis. If and are negative it indicates that African American and Somali American applicants are contacted less than white applicants in Minneapolis. The variable indicates if the email was sent after the new policy has been implemented. We are most interested in the coefficients and these coefficients indicate the change in discrimination after the new policy goes into effect. includes the order the application was sent, type of housing (e.g., single family home, apartment, condo), monthly rent, and zip code fixed effects. We cluster standard errors by ad; results are robust to other clustering choices and are available upon request.

Next, we stratify Equation (1) by whether the Census tract's reported crime per capita is above average. Landlords in areas with higher reported crimes may place more weight on a potential tenant's criminal record, so the policy may have a larger impact in these Census tracts. We additionally split the analysis by neighborhood demographics, which we report in the Supporting Information S1. For these analyses, we cluster standard errors by Census tract.

We are most interested in the coefficients and These variables convey the difference in the change in discrimination after the new policy goes into effect between Minneapolis (where the policy would have clout) and St. Paul (where it was not yet in effect). If and are negative, it indicates that discrimination increased in Minneapolis after the policy passed more than in St. Paul. If they are positive, it indicates that discrimination decreased.

It is possible that landlords begin changing their actions prior to the implementation of the policy in anticipation of it coming into effect. Similarly, landlords in St. Paul may also comply with the policy if they own properties in multiple locations and use a common screening method. Both these situations would bias our results toward zero, since the change at the time of the policy, or the difference between the change in Minneapolis and the change in St. Paul, would be muted.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Changes in ad text after policy implementation

The new policy banned five screening criteria commonly used by landlords: requirement of income three times or higher than monthly rent, security deposit above 1 month rent, criminal background check that includes older convictions,11 specific credit score cutoff, and eviction history older than 3 years. Table 2 shows the percentage of ads that included these criteria in Minneapolis before and after the policy went into effect.

| Two bedroom | Before policy | After policy | p-value | One bedroom/studio | Before policy | After policy | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal history | 10.6% | 4.5% | 0.022 | Criminal history | 3.4% | 4.0% | 0.759 |

| Eviction history | 13.1% | 9.1% | 0.191 | Eviction history | 5.4% | 5.6% | 0.942 |

| Income 3× rent | 11.0% | 6.3% | 0.088 | Income 3× rent | 4.1% | 4.8% | 0.736 |

| Credit score | 8.9% | 2.3% | 0.005 | Credit score | 2.7% | 2.4% | 0.855 |

| Security deposit > monthly rent | 3.5% | 2.8% | 0.681 | Security deposit > monthly rent | 2.4% | 2.4% | 0.987 |

- Note: Percentage of ads that included language in violation of the new policy among large Minneapolis landlords. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021. The fourth and eighth columns shows the p-value from testing if the difference between before and after the policy is different from 0. The left panel (n = 458) includes 2 or more bedrooms. The right panel (n = 420) includes one bedrooms/studios.

As shown in Table 2, these criteria were not very common in ads for one bedroom or studio apartments but relatively common in ads for two or more bedrooms prior to the policy. In larger rental units, the inclusion of the criteria became less common after the policy went into effect. For example, 10.6% of ads for two or more bedrooms in Minneapolis included a phrase prohibiting applicants with any criminal record (including felonies more than 7 years old or misdemeanors more than 3 years old) while only 3.4% of ads for smaller units included this kind of criteria prior to the policy. After the policy went into effect, this dropped to 4.5% of Minneapolis ads for two or more bedroom units. Among ads for larger units in Minneapolis, all five prohibited criteria became much less common after the policy took effect (p < 0.05 for change in criminal history and credit score). Among one-bedroom units, the prohibited criteria were not often included prior to the policy and there was little change after the policy took effect, suggesting the policy was more binding for two or more-bedroom units. Table A5 in Supporting Information S1 shows the change in ad text in St. Paul that there is some evidence of spillover among one-bedroom apartments, which may be more often owned by companies with properties in both Minneapolis and St. Paul. This spillover would bias the triple difference results toward zero.

Taken together, these results suggest that the new policy did impact the criteria that were included in ads for rental housing for two or more bedroom units. Some of the most notable changes occurred to the proportion of ads that prohibited applicants with a criminal history and those that required a specific credit score. While the new policy prohibits landlords from using most older criminal history and from using specific credit score cutoffs to screen tenants, enforcement of this is difficult since landlords are not prohibited from conducting background checks. However, the policy increases the cost for landlords to screen potential tenants based on criminal background and credit score since they are no longer able to include those criteria on their ads. The inclusion of statements such as “no criminal history” was a low-cost screening mechanism for landlords who sought to exclude those with a conviction since it likely discouraged those with a criminal background from applying. For such landlords, the policy raises the cost of screening in the initial stage of the application process since they are less certain about the criminal history of the applicants.

5.2 Impact of policy on discrimination

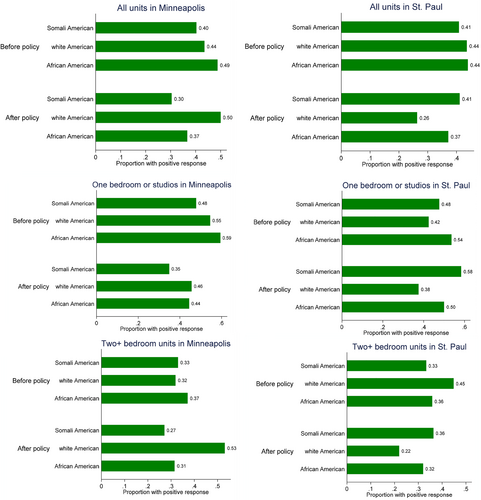

Figure 2 shows the positive responses to email inquiries before and after the policy in Minneapolis among large landlords. Pooling across unit size, the proportion of inquiries that received a positive response before the policy is very similar in Minneapolis and St. Paul; the differences between the two cities prior to the policy are statistically insignificant for Somali Americans (p = 0.93), African Americans (p = 0.39), and white Americans (p = 0.99). Supporting Information S1: Appendix 5 shows the pre-trends in Minneapolis and St. Paul by race and ethnicity; the two cities were trending closely together prior to the policy. After the policy passed, Somali Americans and African Americans experienced a large decrease in positive responses in Minneapolis both for studios/one bedrooms and for units with two or more bedrooms. The decrease for white Americans in Minneapolis was smaller than for African Americans and Somali Americans in the studios/one bedrooms and white Americans were in fact contacted more often than they were before the policy for units with two or more units. In St. Paul, positive responses for all three groups decreased, with white Americans experiencing the largest decrease for both studios/one bedrooms and units with two or more bedrooms. George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020, leading to widespread protests throughout Minneapolis and St. Paul. This may have led to an increase in the salience of racism. The stronger decline in responses to inquiries from white applicants in St. Paul may demonstrate landlords' increased desire to counteract racial inequities.

Proportion of positive responses by race/ethnicity before and after the policy went into effect in Minneapolis among ads listed by companies who have 15 or more units. Left columns includes Minneapolis apartments (n = 879) and right column includes St. Paul (n = 550). Top panel includes all units, middle row includes one bedrooms or studios and bottom panel includes units with two or more bedrooms. Inquiries were sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021.

5.3 Regression results: Impact of policy in Minneapolis

Table 3 displays the results of estimating Equation (1) for ads from Minneapolis. In Column 1, “After policy” shows the change after the policy was implemented in Minneapolis (June 1, 2020). As shown in Column 1, landlords did not respond very differently to inquiries from Somali Americans and African Americans relative to white Americans prior to the policy. That is, prior to the policy we did not detect statistically significant discrimination against Somali American or African American applicants during this initial inquiry stage.

| Outcome variable: Positive contact | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 2+ bedroom | 1 bed/studio | |

| After policy (June 1, 2020—landlords with 15+ units) | 0.0423 | 0.169* | −0.104 |

| (0.0654) | (0.0900) | (0.0931) | |

| Somali American | −0.0328 | −0.00419 | −0.0668 |

| (0.0490) | (0.0695) | (0.0648) | |

| African American | 0.0480 | 0.0425 | 0.0418 |

| (0.0476) | (0.0664) | (0.0633) | |

| After policy and Somali American | −0.158** | −0.238** | −0.0729 |

| (0.0801) | (0.106) | (0.121) | |

| After policy and African American | −0.173** | −0.235** | −0.0839 |

| (0.0821) | (0.109) | (0.127) | |

| Constant | 0.402*** | 0.335*** | −0.172 |

| (0.108) | (0.123) | (0.125) | |

| Observations | 876 | 456 | 420 |

| R-squared | 0.051 | 0.055 | 0.062 |

- Note: Results of linear probability model regressing an indicator for positive contact from the landlord on an indicator variable for being after the policy went into effect (June 1), indicators for Somali American and African American sounding names, and their interactions. Controls include monthly rent, order inquiry was sent, and type of housing. Regressions include ads from large companies in Minneapolis. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021. Robust standard errors clustered by job ad.

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Once the policy was implemented, the proportion of white American names who received a response did not change, but this fell for both Somali American (−0.158, p < 0.05) and African American (−0.173, p < 0.05) inquiries. After the policy was implemented, the proportion of Somali American applicants with positive contact was −0.032–0.158 = −0.190 relative to white Americans and the proportion of African American applicants who received positive contact was 0.048–0.173 = −0.125 relative to white American applicants.

Column 2 in Table 3 shows that the increase in the difference between Somali American and African American applicants relative to white American applicants is large and statistically significant among two or more bedroom units. There is no statistically significant change for Somali American or African American applicants for the studios/one bedroom units (Column 3). Notably, the change in the ad text shown in Table 2 was also largest for the two or more-bedroom units—discrimination increased the most among the same units whose ad text were most affected by the new policy. The presence of a manager provides more monitoring of tenants which may lead to landlords lowering their criteria for tenants in these smaller units. In contrast to our finding, Baldini and Federici (2011) find that in the rental housing market in Italy, Eastern European and Arab applicants experience more discrimination when applying to smaller apartments. Results on differences in discrimination across rental unit types have also varied. For instance, Hanson and Hawley (2011) find less discrimination in inquiries for single-family homes than for apartments and duplexes while Hanson and Santas (2014) find more discrimination for certain groups when applying to single-family homes relative to applying for apartments.

For short-term rentals, Edelman et al. (2017) consider Airbnb listings for an entire unit, a room within a unit, and a shared room and find that racial discrimination is the same whether or not the property is shared. In the years after Edelman et al. (2017), Airbnb has implemented various measures in an effort to combat discrimination on their platform such as the elimination of guest photos prior to booking, making it easier for guests to receive reviews, and increasing the instant booking feature (Airbnb, 2022). While our findings are in the long-term rental context, our results suggest that short-term rental companies may be better served by focusing on policies that increase information such as those that make it easier for guests to accumulate reviews.

Table 4 stratifies the ads with a company listed by perceived gender of the email sender. The increase in discrimination after the policy went into effect is large and statistically significant for emails perceived as coming from men, but not from women. Interestingly, African American men were more likely to be contacted than white American men or Somali American men prior to the policy.

| Outcome variable: Positive contact | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |

| After policy | 0.00254 | 0.0802 |

| (0.0898) | (0.0874) | |

| Somali American | −0.00725 | −0.0485 |

| (0.0725) | (0.0658) | |

| African American | −0.0353 | 0.117* |

| (0.0741) | (0.0627) | |

| After policy and Somali American | −0.102 | −0.229** |

| (0.118) | (0.109) | |

| After policy and African American | −0.0676 | −0.251** |

| (0.121) | (0.116) | |

| Constant | 0.434*** | 0.382*** |

| (0.138) | (0.142) | |

| Observations | 422 | 454 |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.092 |

- Note: Results of linear probability model regressing an indicator for positive contact from the landlord on an indicator variable for being after the policy went into effect (June 1), indicators for Somali American and African American sounding names, and their interactions. Controls include monthly rent, order inquiry was sent, and type of housing. Regressions include only ads from large companies in Minneapolis. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021. Robust standard errors clustered by job ad.

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The stronger impacts for applicants with men's names is consistent with the previous research on the impact of “ban the box” policies in the labor market: the largest impacts of these policies are typically found for Black and Latino men because of upstream biases in education, the labor market, and the criminal justice system resulting in higher incarceration rates for Black and Latino men (Raphael, 2014).

5.4 Differential impacts by neighborhood

Table 5 stratifies Equation (1) by the level of reported crime in the Census tract in 2020. The average Census tract experienced 0.2 reported crimes per capita. In Census tracts with higher-than-average reported crimes per capita, African American and Somali American applicants were contacted at slightly higher rates than white applicants prior to the policy and experienced a large decrease (36% points and 29% points respectively) when the policy went into effect. In neighborhoods with lower-than-average reported crime, the policy had no statistically significant impact for either group.

| Outcome variable: Positive contact | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| <0.2 reported crimes per capita | >0.2 reported crimes per capita | |

| After policy | −0.0106 | 0.125* |

| (0.0851) | (0.0724) | |

| Somali American | −0.0808 | 0.0566 |

| (0.0645) | (0.0814) | |

| African American | 0.00785 | 0.143** |

| (0.0590) | (0.0630) | |

| After policy and Somali American | −0.0713 | −0.289** |

| (0.0951) | (0.119) | |

| After policy and African American | −0.0423 | −0.364*** |

| (0.0925) | (0.0729) | |

| Constant | 0.501*** | 0.121 |

| (0.118) | (0.106) | |

| Observations | 564 | 307 |

| R-squared | 0.030 | 0.135 |

- Note: Results of linear probability model regressing an indicator for positive contact from the landlord on an indicator variable for being after the policy went into effect (June 1), indicators for Somali American and African American sounding names, and their interactions. Regressions include ads with enough information to geocode to a Census tract from large companies in Minneapolis. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021. Controls include monthly rent, order inquiry was sent, and type of housing. Robust standard errors clustered by Census tract.

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The results in Table 5 suggest that the impact of the policy which restricts information on applicants is highest in neighborhoods where landlords may be more concerned about crime. In Supporting Information S1: Appendix 6, we also split the analysis by neighborhood demographics.

5.5 Using St. Paul as control group

To account for any broader secular change in discrimination at the time the policy went into effect, Table 6 uses a triple difference to compare the changes in Minneapolis (where the policy was implemented) to St. Paul (where a similar policy was implemented at a later date).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 2+ bedrooms | One bedroom/studio | |

| After policy | −0.192** | −0.239** | −0.109 |

| (0.0834) | (0.106) | (0.153) | |

| Somali American | −0.0193 | −0.0956 | 0.0484 |

| (0.0611) | (0.0900) | (0.0789) | |

| African American | −0.00698 | −0.107 | 0.112 |

| (0.0631) | (0.0880) | (0.0867) | |

| Minneapolis | 0.00411 | −0.123 | 0.0756 |

| (0.0691) | (0.0984) | (0.0961) | |

| After policy and Somali American | 0.192* | 0.261** | 0.194 |

| (0.106) | (0.132) | (0.210) | |

| After policy and African American | 0.130 | 0.219* | 0.0180 |

| (0.103) | (0.125) | (0.192) | |

| After policy and Minneapolis | 0.239** | 0.423*** | 0.0128 |

| (0.105) | (0.137) | (0.179) | |

| Minneapolis and Somali American | −0.0144 | 0.0900 | −0.109 |

| (0.0783) | (0.113) | (0.101) | |

| Minneapolis and African American | 0.0555 | 0.148 | −0.0619 |

| (0.0790) | (0.110) | (0.108) | |

| After policy and Minneapolis and Somali American | −0.350*** | −0.505*** | −0.271 |

| (0.133) | (0.169) | (0.242) | |

| After policy and Minneapolis and African American | −0.308** | −0.472*** | −0.106 |

| (0.132) | (0.165) | (0.231) | |

| Constant | 0.391*** | 0.420*** | −0.0887 |

| (0.105) | (0.123) | (0.285) | |

| Observations | 1426 | 773 | 653 |

| R-squared | 0.040 | 0.042 | 0.056 |

- Note: Results of linear probability model regressing an indicator for positive contact from the landlord on an indicator variable for being after the policy went into effect (June 12,020), indicators for Somali American and African American sounding names, being in Minneapolis, and their interactions. Controls include monthly rent, order inquiry was sent, and type of housing. Regressions include ads from large companies. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021. Robust standard errors clustered by job ad.

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The coefficients that are of most of interest in Table 6 are the triple interactions (After policy and Minneapolis and Somali American and After policy and Minneapolis and African American). These coefficients show how the racial disparity in positive contact rates changed in Minneapolis compared to St. Paul. The negative values indicate that discrimination worsened in Minneapolis relative to St. Paul after the policy went into effect in Minneapolis and before it went into effect in St. Paul. This pattern is largest for two or more bedroom rental units (Column 2) and not statistically significant for one-bedroom units (Column 3). In this analysis, St. Paul serves as a “counterfactual” or what would have occurred in Minneapolis in the absence of the policy, suggesting that the policy, rather than other secular changes, increased the disparity in positive contact to initial inquiries from rental applicants. This is particularly true because St. Paul passed a similar policy, but it was implemented after the Minneapolis policy. That is, both cities had similar policy approaches but different timing, which allows us to isolate the impact of implementing the policy holding constant less measurable aspects like the political leanings of the population.

5.6 Robustness check 1: Impact of protests over George Floyd's murder

Our analysis of the impact of the new policy in Minneapolis rests on St. Paul serving as an adequate control. One threat to identification comes from unobserved changes in the rental market around the same time as the policy that affect Minneapolis differently relative to St. Paul. One possible source of a change in the rental market in Minneapolis relative to St. Paul is the protests following the murder of George Floyd. The new housing policy went into effect on June 1, 2020. On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was killed in Minneapolis during an arrest after a police officer knelt on his neck. The next day, after videos of the incident became public, protestors took to the streets of Minneapolis. Alongside massive protests was property damage to more than 1500 locations, mostly restaurants and stores (Penrod & Sinner, 2020). The Third precinct of the Minneapolis Police Department and dozens of buildings were burned to the ground, many businesses were damaged extensively, and two people were killed (Jany, 2020). Much of the damage was concentrated in south Minneapolis, particularly near the Third and Fifth precinct police stations. The Star Tribune reported, “Buildings along a 5-mile stretch of Lake Street in Minneapolis and a 3.5-mile stretch of University Avenue in St. Paul's Midway area experienced some of the heaviest damage” (Penrod & Sinner, 2020). It is important to note that property damage affected both Minneapolis and St. Paul. According to a report by St. Paul's Planning and Economic Development department, 330 buildings were damaged in the city (Nelson, 2020).

Because the protests likely impacted the housing market in the affected neighborhoods and was close in time to the implementation of the new policy, it is possible our analysis is affected by the impact of the protests. To examine this, Table 7 repeats the main analysis but excludes rental units in south Minneapolis where the bulk of property damage occurred (zip codes 55406 and 55407). Column 1 shows the change in discrimination in Minneapolis after the policy went into effect. Column 2 shows the triple difference—comparing the change in discrimination in Minneapolis to St. Paul.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| After policy | 0.0352 | −0.194** |

| (0.0696) | (0.0834) | |

| Somali American | −0.0280 | −0.0201 |

| (0.0514) | (0.0612) | |

| African American | 0.0272 | −0.00607 |

| (0.0497) | (0.0632) | |

| After policy and Somali American | −0.159* | 0.191* |

| (0.0866) | (0.106) | |

| After policy and African American | −0.148* | 0.128 |

| (0.0861) | (0.103) | |

| Minneapolis | 0.00998 | |

| (0.0701) | ||

| After policy and Minneapolis | 0.234** | |

| (0.108) | ||

| Minneapolis and Somali American | −0.00948 | |

| (0.0798) | ||

| Minneapolis and African American | 0.0330 | |

| (0.0804) | ||

| After policy and Minneapolis and Somali American | −0.348** | |

| (0.137) | ||

| After policy and Minneapolis and African American | −0.281** | |

| (0.134) | ||

| Constant | 0.376*** | 0.373*** |

| (0.111) | (0.108) | |

| Observations | 803 | 1353 |

| R-squared | 0.045 | 0.035 |

- Note: Results of linear probability model regressing an indicator for positive contact from the landlord on an indicator variable for being after the policy went into effect for large landlords (June 1), indicators for Somali American and African American sounding names, and their interactions. Column additionally includes an indicator for Minneapolis and interactions. Columns 1 includes only Minneapolis observations (excluding 55,406 and 55,407 zip codes) from companies who likely have 15+ units. Column 2 includes all observation (excluding 55,406 and 55,407 zip codes) from large companies. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021.Controls include monthly rent, order inquiry was sent, type of housing, and zip code fixed effects. Robust standard errors clustered by job ad.

- ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Column 1 in Table 7 shows that after excluding rental units in south Minneapolis, the increase in discrimination in Minneapolis after the policy went into effect remains similar in magnitude and is statistically significant. Column 2 shows that the change in Minneapolis is larger than St. Paul and remains similar in magnitude to that found in Table 6 and is statistically significant. Thus, there are no substantive differences to our results when we exclude rental units in the parts of Minneapolis most affected by the protests.

5.7 Robustness check 2: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

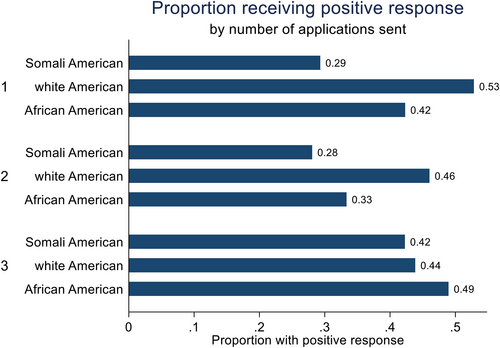

As mentioned in the data section, we altered our data collection process because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We began data collection in January 2020 and sent three emails to each landlord. Because the stay-at-home order in March 2020 decreased activity in the rental housing market, landlords may have become suspicious of our emails. While we sent one email per ad from April 2020 to August 2020, we sent two emails per ad from August 2020 to March 2021. Because our applicants are in competition with one another for the same rental property, discrimination could increase when we send more inquiries. The triple-difference design should account for the difference because we did not make differing changes in data collection between Minneapolis and St. Paul. However, to check if the number of applications sent alters discrimination, we examine the proportion of responses with positive contact by race/ethnicity based on how many inquiries were sent to each ad.

Figure 3 shows that increasing the number of applications sent does not increase discrimination; the difference in responses to white American, Somali American, and African American inquiries is very similar between when one or two inquiries were sent and is in fact smaller when three inquiries were sent. This suggests that changing the number of inquiries sent due to COVID-19 is not driving our results.

Proportion of inquiries that received a positive response by the number of total applications sent to the ad and the race/ethnicity of the name used. Includes large landlords in Minneapolis. Inquiries sent between January 1, 2020 and February 28, 2021. n = 879.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we examine the impact of a policy that reduced a wide range of information about rental housing applicants. We show that this policy affected landlord behavior: after the policy went into effect, ads for two or more bedroom units in Minneapolis dramatically reduced the use of credit score cutoffs, text like “Clean background check” or “No felonies,” and income or security deposits requirements that violated the new policy. We additionally find increased discrimination in Minneapolis against both Somali American and African American applicants after the policy went into effect. This increase was largest for men, in Census tracts with more reported crimes per capita, and for units with two or more bedrooms. To account for possible secular changes occurring at the same time, we use a triple-difference model comparing changes in Minneapolis (where the policy went into effect) to changes in St. Paul (where a similar policy went into effect later). We confirm our finding that discrimination in Minneapolis increased relative to St. Paul after the policy went into effect in Minneapolis.

Policies that limit information on applicants, whether in employment or housing, are typically intended to decrease disparities and increase access. Our analysis sheds light on the subtle ways in which racism can lead to unintended negative impacts of well-intentioned policies. Minneapolis policymakers sought to increase access to rental housing for people who would have previously been screened out based on criminal record, credit history, and income. Indeed, we find that ads requiring specific credit scores or banning applicants with criminal records fell dramatically after the policy went into effect—the policy achieved that aspect of its goal.

However, because this policy operates in a society with large racial disparities in income, credit score, and criminal history, restricting information on individual applicants appears to have caused landlords to rely more on stereotypes and increased discrimination against Somali American and African American renters. The discrimination we observe occurs prior to submitting a formal rental application and largely manifests in the landlord simply not responding to inquiries from Somali American and African American applicants. This form of discrimination is virtually impossible for an individual applicant to detect or report and hard for policymakers to combat. We find that a race-neutral policy, implemented in a stratified society, has a biased result that primarily impacts African American and Somali American men.

Research on racial inequities in housing often focus on discrimination in mortgage lending because of homeownership's role in wealth building (e.g., Ladd (1998), Apgar and Calder (2005), Charles and Hurst (2002), though others note that homeownership alone does not significantly reduce the wealth gap (Darity et al., 2018)). While rental housing does not build wealth, reducing discrimination in the rental housing market is important for increasing housing stability. This is particularly true in Minnesota, where the vast majority of African Americans (78%) and Somali Americans (90%) rent their homes (MNSDC, 2018). Understanding how to increase access to housing while also reducing rental housing discrimination is an essential component of developing policies to increase racial equity in housing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project would not have been possible without our amazing team of RAs. We are incredibly grateful for the hard work of Isabel Honzay, Karisa Johnson, Mumtas Mohamed, Giang Nguyen, Anchee Nitschke Durben, Emily Sailors, Cheyanne Simpson, and Emily Young. We also thank Peter Blair, Donn Feir, Andrew Goodman-Bacon, Gary Painter, Kristine West, and the seminar participants at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth for their insightful comments and suggestions. Support for this research was provided in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Policies for Action program. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the view of the Foundation. Support for this work was provided in part by the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The views represented here do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, nor the Board of Governors. We thank the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, University of St. Thomas, and St. Catherine University for generously providing funding for this project.

ENDNOTES

- 1 Flage (2018) provides a meta-analysis for this literature.

- 2 These first names are of Muslim origin and not specific to Somali Americans. However, in the Twin Cities context, Somali Americans are the largest, most visible Muslim group.

- 3 See Supporting Information S1: Appendix 1 for a full list of email addresses.

- 4 See Supporting Information S1: Appendix 1 for more details on the email inquiries.

- 5 For example, one response stated they had not gotten any inquiries for 10 days and then got three in one day (the three inquiries we sent) and was concerned it was a scam. Because the landlord was not receiving any other inquiries, the time lag was insufficient to separate the applicants from each other sufficiently to avoid suspicion. Another response asked if our applicants were related to each other. These suspicious responses only occurred after the COVID-19 pandemic began and did not occur again after we reduced the number of inquiries sent. Importantly, the landlords appeared suspicious of all three inquiries; we observed no difference by race/ethnicity in suspicious responses.

- 6 See Supporting Information S1: Appendix 1 for more details on the email inquiries.

- 7 Data available: https://opendata.minneapolismn.gov/datasets/cityoflakes::crime-data/about.

- 8 We use the date that the email inquiry was sent to classify the observation as before or after the policy. Inquiries were sent throughout the implementation of the policy.

- 9 We are unable to analyze the impact of the policy on landlords with fewer than 15 units. Very few ads with the company name listed are from companies with fewer than 15 units. Ads without a company name listed are a mix of companies with more than 15 units and fewer than 15 units - we therefore don't know the relevant policy implementation date for these ads.

- 10 As shown in Supporting Information S1: Appendix 2, there is no evidence that there was any change in the tendency of landlords to include their name in the ad at the time of the policy implementation. Ads with a company name had similar average rent to those without a name, but were less often two or more bedrooms, less often in Minneapolis, and more likely to respond positively to the inquiry.

- 11 The law bars landlords from considering misdemeanors that are older than 3 years and felonies older than 7 years. For certain felonies, landlords cannot consider convictions that are older than 10 years.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [OpenICPSR] at https://doi.org/10.3886/E230902V1 reference number [COEP-Jun-2024-0085] (Rho & Marina, 2025).