Effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of sacral neuromodulation for idiopathic slow-transit constipation: a systematic review

Stella C. M. Heemskerk and Aart A. van der Wilt contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Aim

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) is a minimally invasive treatment option for functional constipation. Evidence regarding its effectiveness is contradictory, driven by heterogeneous study populations and designs. The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of SNM in children and adults with refractory idiopathic slow-transit constipation (STC).

Method

OVID Medline, OVID Embase, Cochrane Library, the KSR Evidence Database, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database and the International HTA Database were searched up to 25 May 2023. For effectiveness outcomes, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were selected. For safety outcomes, all study designs were selected. For cost-effectiveness outcomes, trial- and model-based economic evaluations were selected for review. Study selection, risk of bias and quality assessment, and data extraction were independently performed by two reviewers. For the intervention ‘sacral neuromodulation’ effectiveness outcomes included defaecation frequency and constipation severity. Safety and cost-effectiveness outcomes were, respectively, adverse events and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

Results

Of 1390 records reviewed, 67 studies were selected for full-text screening. For effectiveness, one cross-over and one parallel-group RCT was included, showing contradictory results. Eleven studies on safety were included (four RCTs, three prospective cohort studies and four retrospective cohort studies). Overall infection rates varied between 0% and 22%, whereas reoperation rates varied between 0% and 29%. One trial-based economic evaluation was included, which concluded that SNM was not cost-effective compared with personalized conservative treatment at a time horizon of 6 months. The review findings are limited by the small number of available studies and the heterogeneity in terms of study populations, definitions of refractory idiopathic STC and study designs.

Conclusion

Evidence for the (cost-)effectiveness of SNM in children and adults with refractory idiopathic STC is inconclusive. Reoperation rates of up to 29% were reported.

What does this paper add to the literature?

The level of evidence for sacral neuromodulation in functional constipation is low (partly) due to heterogeneous study populations.

Hence, there is a need for better patient selection. The current study answers to this need as it reviewed the available literature in a homogenous patient group with refractory idiopathic slow-transit constipation.

INTRODUCTION

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) is a minimally invasive surgical technique to enable electrical stimulation of sacral nerves. The technique of SNM consists of a test stimulation phase, to assess its initial treatment effect, followed by implantation of a permanent implantable pulse generator (IPG) in case of a successful test stimulation [1]. SNM was initially developed to treat urinary incontinence [2-4]. For children and adults with functional constipation (FC), several studies have suggested that SNM might be effective [5-7]. FC is a functional bowel disorder, defined by the Rome IV criteria, with a prevalence of 16% in Europe [8, 9]. Several subtypes of FC can be distinguished: normal-transit constipation, slow-transit constipation (STC) and outlet obstruction [10]. Approximately 1% of patients with FC have intractable symptoms and are refractory to conservative treatment, of which 15%–30% have idiopathic STC [11]. Idiopathic STC is characterized by the absence of outlet obstruction and a slow passage of faeces due to dysmotility of the colon [11, 12]. The exact pathophysiology of idiopathic STC remains unclear, but studies suggest that intrinsic neuronal abnormalities might lead to an altered colonic motility [11, 13].

It is still unclear in what manner SNM can affect patients with idiopathic STC. Hypotheses suggest that both a local effect on the extrinsic neural control of the bowel as well as activation of different areas in the central nervous system play a role [14, 15]. Colonic manometry in STC patients shows deficient or absent high-amplitude propagating sequences [16, 17]. SNM has been shown to induce motor responses in the proximal and distal colon in STC patients: stimulation increases the frequency of antegrade and retrograde propagating sequences, as well as the frequency of high-amplitude propagating sequences which originate in the caecum and extend to the full length of the colon [18]. These mechanisms would lead to a shorter transit time and relief of symptoms. Therefore, we hypothesized that this specific group of patients might especially benefit from electrical stimulation with SNM.

Evidence on the effectiveness of SNM for idiopathic STC, however, is conflicting and of suboptimal quality [19, 20]. The European guidelines state that despite the low success rate of SNM it is justified because of its low complication rate. However, the level of evidence was considered low and better patient selection was considered to be an important goal for further studies [21]. The aim of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of SNM versus conservative treatment in a specific subgroup of children and/or adults with FC suffering from refractory idiopathic STC.

METHOD

A systematic literature review was conducted according to the Cochrane Handbook, and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [22]. The study protocol is available on PROSPERO (CRD42021229965).

Search strategy and study selection

Three search strategies were performed on three outcome categories: effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness (Appendix S1). Databases were last searched on 25 May 2023. Inclusion criteria were based on the principle of Participants, Interventions, Comparison, Outcome and Time [23]. Studies were included when the study population consisted of children and/or adults with functional constipation who were diagnosed with refractory idiopathic STC. For the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness search, studies including patients with mixed FC subtypes were included when results were reported separately for each subtype. For the safety search, as SNM complications might be less dependent on the FC subtype, studies were eligible if ≥67% of the population was diagnosed with idiopathic STC. When the results were not stratified for FC subtype, the results for the total population are reported in this systematic review. For all searches, the intervention was SNM and the control treatment (if applicable) was any (combination of) conservative treatment such as oral and/or rectal laxatives, enemas and retrograde colonic irrigation. There was no limitation on publication year. Nonhuman studies, conference abstracts and studies for which no full text could be retrieved were excluded.

Effectiveness search

OVID Medline, OVID Embase and the Cochrane Library were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing SNM with conservative treatment in patients with refractory idiopathic STC. Studies comparing active SNM with sham stimulation were included if patients were, next to (sham) stimulation, also treated with any type of conservative treatment. Studies were eligible in case they reported (one of) the following outcome measures: defaecation frequency, reduction in constipation symptoms, constipation severity, fatigue and (health-related) quality of life.

Safety search

OVID Medline, OVID Embase, the Cochrane Library and the KSR Evidence Database were searched for meta-analyses, systematic reviews, RCTs, prospective nonrandomized comparative/cohort studies, retrospective nonrandomized cohort studies, case–control studies and case series. Studies were eligible when they reported the number and type of any adverse events in patients with idiopathic STC treated with SNM.

Cost-effectiveness search

OVID Medline, OVID Embase, the Cochrane Library, the KSR Evidence Database, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database and the International HTA Database were searched for trial- and model-based economic evaluations on SNM for idiopathic STC. Studies were eligible when they reported incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

Screening

For each search strategy, titles and abstracts were imported in Endnote X9.3 and duplicates were removed. Records were independently screened for eligibility by two reviewers (AW, BP). Subsequently, full-text articles were retrieved and independently evaluated by two reviewers (AW, BP). Disagreements were resolved through a discussion between the reviewers or by consulting a third reviewer (SH). Reference lists of included studies were checked for potentially eligible studies that were missed. These records were also screened.

Data extraction

Data extraction of the included articles was independently performed by two reviewers (AW, BP). The following information was extracted: author, year, title, journal, type of study, methods, population, baseline characteristics and outcome measures as described above.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Two reviewers (AW, BP) independently assessed the risk of bias of included (cross-over) RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool and critically appraised the quality of included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists for case studies and economic evaluations [24-26]. Disagreements were resolved through a discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (SH).

RESULTS

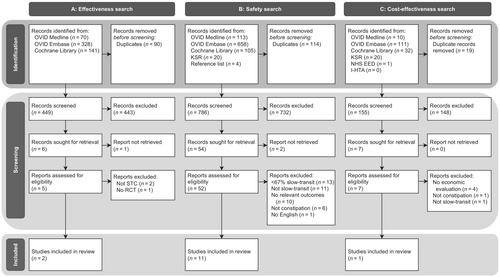

The results per search strategy are visualized in Figure 1. Table 1 presents the characteristics of included studies per search strategy. Risk of bias and quality assessments of included studies are presented in Figures S1–S3. Table S1 lists the inclusion criteria of the included studies and Table S2 lists the diagnostic methods and definitions used in the included studies to respectively measure and define idiopathic STC.

| First author, year, country | Study type | Study populationa | Primary outcome | Intervention | Control | Total | PNE/TLP | Permanent SNM | Loss to follow-up (after permanent SNM) | Follow-up period (months) and range | Risk of biasb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies included for both effectiveness and safety outcomes | |||||||||||

| Dinning (2015), Australia [27] | Cross-over RCT | Adults with STC, refractory to conservative treatment | More than 2 days per week with bowel movement associated with a feeling of complete evacuation for at least 2 or 3 weeks during suprasensory stimulation |

Suprasensory (14 Hz, 300 μs) and subsensory (perceived stimulation reduced by 0.2 V) SNM: permanent IPG after 3 weeks of PNE in all patients irrespective of PNE response, use of conservative treatment was permitted |

Sham stimulation (pulse width and frequency set to 0), use of conservative treatment was permitted | 59 | 59 (100% STC) | 55 (100% STC) | 2 | 4.5 (18 weeks) | Low |

| Heemskerk (2023), The Netherlands [28] | Parallel-group RCT | Adolescents and adults with idiopathic STC refractory to conservative treatment | Average defaecation frequency ≥3 per week at 6 months | SNM: permanent IPG after 4 weeks of TLP in patients with defaecation frequency ≥3 per week | Personalized conservative treatment | 67 | 41 (100% STC) | 31 (100% STC) | 5 | 12 | Some concerns |

| Studies included for safety outcomes | |||||||||||

| Carriero (2010), Italy [29] | Prospective cohort | Adults with STC refractory to conservative treatment | Mean number of bowel movements per week and Wexner score | SNM: permanent IPG after 4 weeks of TLP in patients with an appearance of spontaneous necessity of evacuation and a referred improvement of quality of life | No control | 13 | 13 (100% STC) | 11 (100% STC) | 0 | 22 (12–36) | NA |

| Gortazar de las Casas (2019), Spain [30] | Retrospective cohort | Adults with chronic constipation according to the Rome III criteria | Patient satisfaction | SNM: permanent IPG after TLP test period in patients who fulfilled one or more of the following criteria: (a) a reduction to <50% in the number of episodes of straining and/or a decrease by >50% in the sensation of incomplete evacuation; (b) a subjective improvement of symptoms in the absence of an increase in the use of laxatives, enemas or manual stimulation; and (c) an increase in frequency of evacuation to ≥3 bowel movements per week | No control | 29 | 29 (69% STC) | 24 (% STC not reported) | Not reported | 59 (7–108) | NA |

| Kamm (2010), Australia, UK, The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Austria [31] | Prospective cohort | Adults with chronic idiopathic constipation, refractory to conservative treatment | Defaecation frequency, straining, sensation of incomplete evacuation | SNM: permanent IPG after PNE test period in patients with at least an increase in evacuation frequency to three or more bowel movements per week, and/or a reduction by ≥50% in the number of episodes of straining and/or a decrease by >50% in the sensation of incomplete evacuation | No control | 62 | 62 (81% STC) | 45 (82% STC) | 0 | 28 (1–55) | NA |

| Naldini (2010), Italy [32] | Retrospective cohort | Adults with STC, refractory to conservative treatment | Wexner constipation score and quality of life | SNM: permanent IPG after TLP test period in patients with a disappearance of the need for laxative medication (>90%), disappearance of the need for enema administration (>90%), appearance of spontaneous evacuation, improved quality of life | No control | 15 | 15 (100% STC) | 9 (100% STC) | 0 | 42 (24–60) | NA |

| Patton (2016), Australia [33]c | Prospective cohort | Adults with STC, refractory to conservative treatment | More than 2 days per week with bowel movement associated with a feeling of complete evacuation | SNM: included patients who had already received a permanent IPG in the Dinning et al. (2015) RCT [27] | No control | 53 | 53 (100% STC) | 53 (100% STC) | 38 | 24 | NA |

| Schiano di Visconte (2019), Italy [34] | Retrospective cohort | Adults with STC, according to the Rome III criteria, refractory to conservative treatment | Not defined | SNM: Permanent IPG after 1 month TLP test period in patients in which a 50% symptom reduction was achieved | No control | 63 | 25 (100% STC) | 21 (100% STC) | 10 | 60 (33–69) | NA |

| Sharma (2011), UK [35] | Prospective cohort | Adults with chronic idiopathic constipation, refractory to conservative treatment | Bowel diary (details not reported) | SNM: permanent IPG after 2 weeks of PNE test stimulation in patients with ≥50% improvement in bowel diaries | No control | 21 | 21 (90% STC) | 11 (% STC not reported) | 1 | 38 (18–62) | NA |

| Yiannakou (2019), UK [36] | Cross-over RCT | Adults with chronic constipation according to Rome-III criteria, refractory to conservative treatment | ≥0.5 reduction in PAC-SYM at 6 months | SNM at 75% of the subsensory stimulation threshold ePNE/TLP test period after which a permanent IPG was implanted in all responders with a ≥25% improvement TiLTS-VAS score | Sham stimulation (not specified) | 45 | 45 (67% STC) | 27 (% STC not reported) | 1 | 6 | Some concerns |

| Zerbib (2016), France [37] | Cross-over RCT | Adults with chronic constipation, refractory to conservative treatment | Proportion of patients with a response during each treatment period (active vs. sham), defined by the same criteria as test stimulation success (next column) | SNM: permanent IPG after 3 weeks of PNE in patients who fulfilled at least one of the following criteria: increase in evacuation frequency from less than 2, to ≥3 bowel movements per week; reduction of ≥50% in the number of defaecation episodes with straining; or decrease of ≥50% in defaecation episodes with a sense of incomplete evacuation | Sham stimulation (not specified) | 36 | 36 (78% STC) | 20 (% STC not reported) | 2 | 12 | Some concerns |

| Studies included for cost-effectiveness outcomes | |||||||||||

| Heemskerk (2023), The Netherlands [38] | Trial-based economic evaluation | Adolescents and adults with idiopathic STC refractory to conservative treatment | Average defaecation frequency ≥3 per week at 6 months | SNM: permanent IPG after 4 weeks of TLP in patients with defaecation frequency ≥3 per week | Personalized conservative treatment | 65 | 41 (100% STC) | 31 (100% STC) | 5 | 6 | NA |

- Abbreviations: ePNE, enhanced peripheral nerve evaluation (equivalent to the tined lead procedure); IPG, implantable pulse generator; NA, not applicable; PAC-SYM, patient assessment of constipation symptoms score; PNE, peripheral nerve evaluation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SNM, sacral neuromodulation; STC, slow-transit constipation; TiLTS-VAS, a visual analogue scale from 0 to 100 administered in the TiLTS trial; TLP, tined lead procedure.

- a Table S1 (Appendix S1) lists detailed study population descriptions and criteria, Table S2 lists definitions of STC.

- b Risk of bias of RCTs was measured with the ROB2-tool. The quality of nonrandomized studies was critically appraised using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists for case studies and economic evaluations (not included in table).

- c Long-term follow-up study of Dinning et al. [27].

Effectiveness

After title and abstract screening of 449 records, six articles were included for full-text screening. Two studies were excluded because results were not reported separately for idiopathic STC [36, 37]. Individual patient data for these studies were requested but were not available. One long-term follow-up study of a RCT was excluded as this was a prospective cohort study in patients who participated in a RCT [39]. Full-text reports of two conference abstracts were requested. For one no full-text report was available [40]. The other was from our own research group. In the meantime this study was published and included in the review [28]. This resulted in the inclusion of two RCTs: one cross-over RCT with a low risk of bias and one parallel-group RCT with some concerns regarding risk of bias (Table 1; Figures 1 and S1) [27, 28].

Dinning et al. [27] included patients aged 18–75 years with refractory STC that reported complete bowel movements on fewer than 3 days per week. After 3 weeks of test stimulation in 59 patients (median age 42 years, n = 5 (7%) male), 55 patients received a permanent IPG irrespective of treatment response. Hereafter, two cross-over phases were performed comparing suprasensory and subsensory SNM with sham stimulation during which patients were permitted to use additional conservative treatment. Each phase consisted of eight weeks: 3 weeks of sub−/suprasensory SNM or sham stimulation, followed by a 2-week wash-out period, followed by another 3 weeks of sub−/suprasensory SNM or sham stimulation. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who, on more than 2 days per week, for at least 2 or 3 weeks, reported a bowel movement associated with a feeling of complete evacuation during permanent suprasensory stimulation. There was no significant difference between suprasensory SNM and sham stimulation (29.6% achieved treatment response with suprasensory SNM versus 20.8% with sham stimulation, p = 0.23). Compared with baseline, however, both suprasensory SNM and sham stimulation caused significant changes in the days per week with a feeling of complete evacuation and normal stool, and weekly pain and bloating scores. There was no significant difference between subsensory SNM and sham stimulation (25.4% achieved treatment response in both groups, p = 0.95). Compared with baseline, significant improvements were observed during both subsensory SNM and sham stimulation, with the same characteristics as during the suprasensory SNM versus sham stimulation phase.

Heemskerk et al. [28] included patients aged 14–80 years with treatment-resistant idiopathic STC with a colonic transit time >62 h, who defaecated fewer than three times a week and fulfilled the Rome IV criteria for FC. Sixty-seven patients were assigned in a 3:2 ratio to SNM [n = 41, median age 31 years, n = 3 (7%) male] or personalized conservative treatment (PCT) [n = 26, median age 32 years, n = 2 (8%) male]. In the SNM-group, 41 patients underwent a 4-week test stimulation, 31 (76%) of whom were successful and received a permanent IPG. The primary outcome measure was treatment success, defined as an average spontaneous defaecation frequency of ≥3 per week. After 6 months of follow-up, 22 (53.7%) patients in the SNM group met the primary outcome versus 1 (3.8%) patient in the PCT group (p = 0.003). Wexner constipation, fatigue scores and constipation-specific and health-related quality of life (PAC-QOL, EQ-5D-5L, EQ-VAS, ICECAP-A) scores were also significantly improved after 6 months of follow-up in favour of the SNM group (p < 0.001). No significant difference between the groups was found in the proportion of defaecations associated with straining or a sense of incomplete evacuation after 6 months of follow-up. Similarly, adolescent KIDSCREEN-27 scores did not differ significantly between the groups after 6 months of follow-up. A subset of patients with an IPG at 6 months follow-up (n = 25) was followed until 12 months. The 6 month Wexner constipation scores and EQ-5D-5L VAS and utility scores in this group were maintained after 12 months' follow-up.

Due to heterogeneity in terms of study designs and outcome measures, results were not pooled in a meta-analysis.

Safety

After title and abstract screening of 786 records, 54 articles were included for full-text screening of which 52 were retrieved. In total, 11 studies were included: four RCTs, three retrospective cohort studies and four prospective cohort studies (Table 1, Figure 1) [27-33, 35-37]. The risk of bias of the included RCTs was low to intermediate (Figure S1). The quality assessment of the observational studies was intermediate (Figure S2). Table 2 displays the types and numbers of adverse events per study.

| First author, year | Follow-up period in months (range) | Permanent SNM | Infection (permanent SNM) | Pain (IPG site) | IPG repositioning/lead revision | Pain (abdominal, leg, back, anal) | Gastrointestinal complaints | Urological complaints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriero (2010) [29] | 22 (12–36) | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dinning, (2015) [27] | 4.5 (18 weeks) | 55 | 12 (22%) | 32 (58%) | 0 | 7 (13%) | 0 | 17 (31%) |

| Gortazar de las Casas (2019) [30] | 59 (7–108) | 24 | 5 (21%) | 5 (21%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heemskerk (2023) [28] | 12 | 31 | 2 (6%) | 10 (32%) | 9 (29%) | 9 (29%) | 16 (52%) | 2 (6%) |

| Kamm (2010) [31] | 28 (1–55) | 45 | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 7 (16%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Naldini (2010) [32] | 42 (24–60) | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patton (2016) [33]a | 24 | 53 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Schiano di Visconte (2019) [34] | 24 (24–60) | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sharma (2011) [35] | 38 (18–62) | 11 | 1 (9%) | 0 | 2 (18%) | 4 (36%) | 0 | 0 |

| Yiannakou (2019) [36]b | 6 | 27 | 3 (11%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zerbib (2016) [37]c | 12 | 20 | 3 (15%) | 5 (25%) | 2 (10%) | 9 (45%) | 4 (20%) | 2 (10%) |

| TOTAL | 307 | 29 | 55 | 22 | 32 | 20 | 23 |

- Abbreviations: IPG, implantable pulse generator; SNM, sacral neuromodulation.

- a Long term follow-up study of Dinning et al. (2015) [27].

- b Yiannakou et al. (2019) [36] reported 13 wound infections, of which 10 occurred during a prolonged enhanced peripheral nerve evaluation test phase. Furthermore, 45 nonsevere complications related to sacral neuromodulation were reported but remained unspecified.

- c Zerbib et al. (2016) [37] reported five wound infections, of which two occurred during the peripheral nerve evaluation test phase.

Out of three cross-over RCTs, only Dinning et al. [27] specified that there was no difference in the incidence of complications between active and sham stimulation [27]. In 55 patients with permanent IPGs, 73 adverse events were recorded in a follow-up period of 18 weeks: the majority were pain at the IPG site (44%), urological adverse events (23%) and wound infections (16%). Patton et al. [33] reported the long-term results of this population. The Yiannakou et al. [41] study was terminated prematurely because of an infection rate of 22% (10 out of 45 patients) during the SNM test period. This RCT opted for a longer tined lead testing phase of 6 weeks. In nine patients tined leads were urgently removed after infection. Out of 27 patients with a permanent IPG, three patients had the IPG removed at the 6-month follow-up due to infection. Zerbib et al. [42] reported eight adverse events in 20 patients with permanent IPGs after 12 months' follow-up. Another 25 adverse events in 11 patients were reported, without certain relation to treatment. In the study by Schiano di Visconte et al. [34] no adverse events were reported; however, after 60 months of follow-up the IPG-system was explanted in 9 of 21 patients because of the end of any therapeutic effect.

Two observational studies with a potential overlap in included patients reported no complications [29, 32]. Sharma et al. [35] reported an IPG infection, which was successfully treated with antibiotics, and four displacements of the temporary lead during the PNE test phase. Kamm et al. [31] also reported that six out of 62 patients experienced lead damage or loss of efficacy during the PNE test period. This resulted in reoperations and potentially produced false-negative test results.

Overall, the infection rate reported in the included studies varied between 0% and 22% and reoperation rates varied between 0% and 29%.

Cost-effectiveness

After title and abstract screening of 155 records, seven articles were included for full-text screening. One of these full-text articles was requested and retrieved from our own research group after the conference abstract came up in the search. This article, which is currently in submission, was included (Table 1, Figures 1 and S3). Heemskerk et al. [28, 38] performed an economic evaluation alongside a parallel-group RCT, included in the effectiveness search. Two incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated with a time horizon of 6 months. For the cost–utility analysis the ICER was €147 715.14 per quality adjusted life year (QALY). With a maximum threshold of €80 000 per QALY, SNM had zero probability of being cost-effective. For the cost-effectiveness analysis the ICER was €28 208.84 per successfully treated patient. Secondary analysis showed that ICERs were more favourable for SNM when dispersing SNM material cost over a period of 5 years.

DISCUSSION

With 12 unique studies included in this systematic review there is limited evidence regarding effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of SNM for patients with refractory idiopathic STC. The RCTs on effectiveness of SNM reported conflicting results: whereas Dinning et al. concluded that SNM did not improve the frequency of complete bowel movements, Heemskerk et al. concluded that SNM was an effective treatment, resulting in a defaecation frequency of ≥3 per week in 53.7% of the SNM patients (compared with 3.8% with PCT) [27, 28]. Due to heterogeneity in RCT designs (cross-over versus parallel-group design; sham-controlled versus usual care) and outcome measures, comparing these studies is difficult. For example, in Dinning et al. all patients received an IPG irrespective of the test-phase response. Comparing the findings in this population with a selection of patients who benefitted from stimulation during the test phase, and hence received an IPG, is complex. Therefore, based on these two RCTs, the effectiveness of SNM for refractory idiopathic STC remains inconclusive.

Regarding the safety of SNM for refractory idiopathic STC, five studies were initially included after full-text screening. However, the indication for which SNM is used might not directly affect the type of adverse events as the events are most likely related to the SNM itself and not to the population being treated. This assumption was supported by a systematic review that considered SNM to be a safe treatment option for the indications of lower urinary tract dysfunction [43]. Moreover, another systematic review did not report a difference in incidence of complications between patients suffering from FC versus faecal incontinence [44]. Based on this assumption, the inclusion criteria for the safety search in this current review were widened, and studies with a study population consisting of ≥67% idiopathic STC patients were included.

Comparing the reported complication rates was complicated due to differences in type, number and severity of adverse events in the included studies. There might be reporting bias, which is especially relevant for subjective adverse events such as pain and some gastrointestinal and urological complaints. Infection rates of up to 22% are reported, with a potentially major impact when explant of the device is needed. The vulnerability of foreign material to become infected can only be aimed to be suppressed by meticulous surgical procedures with special attention to aseptic conditions. However, included studies showed that infections on the device also occurred after long-term follow-up. Reported infection rates are therefore probably also dependent on follow-up length. An additional problem is the increased infection risk after a reoperation as a result of device failure or low battery. Furthermore, there might be a lack of consensus about the definition, and therefore reporting, of complications. For example, device reprogramming because of diminishing effectiveness is a burden for both patient and healthcare providers. However, reprogramming is often not reported, despite potentially being indicative for treatment failure. Differences in complication rates between studies might also partly arise from the demographic differences between populations suffering from symptoms of different indications for SNM.

Only one study assessed the cost-effectiveness of SNM for refractory idiopathic STC. In a short time period of 6 months SNM was not cost-effective [38]. However, sensitivity analyses showed that possibility of cost-effectiveness increased when SNM material costs were dispersed over a longer time period. This should be interpreted with caution as it was assumed that the effect of SNM remained unchanged. An excluded full-text record assessed the cost-effectiveness of SNM in children and adolescents with mixed FC subtypes and concluded that, from a healthcare perspective with a time horizon of 3 years, SNM might be a cost-effective treatment option when compared with conservative treatment [45]. A mean ICER of €12 328 per QALY was reported in the base case analysis and ICERs ranged from €6422 per QALY to €36 652 per QALY based on sensitivity analyses [45]. In faecal incontinence, an ICER of £25 070 per QALY was reported based on direct and indirect medical costs, comparing SNM versus conservative treatment [46]. However, care is required when comparing FC with faecal incontinence as both SNM and conservative treatment costs might differ between these indications, and consequently influence the ICERs.

The findings of this study are limited due to the small number of available studies. Furthermore, the included studies were heterogeneous in terms of study population (i.e. various definitions of FC and idiopathic STC), study design and definitions of treatment success. Previous systematic reviews on SNM in FC and idiopathic STC reported similar observations [19, 47]. This heterogeneity complicates between-study comparisons and might also explain the contrasting success rates of SNM for FC and idiopathic STC in the available literature. Standardization of patient selection and clinical outcomes is an unmet need in studies on (SNM for) idiopathic STC. A step towards standardization of clinical outcomes might be the development of core outcome set: a minimal set of outcomes to be included in every (clinical) study regarding treatment for a certain health condition [48]. This will facilitate comparisons between the direct effects of different treatment options in refractory idiopathic STC [47, 48].

CONCLUSION

Based on the insufficient availability of evidence, the effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of SNM for patients with refractory idiopathic STC remains inconclusive. Further research of good methodological quality is needed to evaluate whether SNM is effective for this select group of patients, whether complication rates are acceptable and if the treatment is cost-effective.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Stella C. M. Heemskerk: Conceptualization; writing – original draft; methodology; investigation; writing – review and editing; project administration; validation; formal analysis; supervision; visualization. Aart A. van der Wilt: Investigation; writing – review and editing; writing – original draft; validation; formal analysis; methodology. Bart M. F. Penninx: Investigation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; visualization; methodology; formal analysis; project administration. Jos Kleijnen: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; methodology; validation. Jarno Melenhorst: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Carmen D. Dirksen: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; methodology; supervision; resources; validation. Stéphanie O. Breukink: Resources; supervision; writing – review and editing; methodology; conceptualization; investigation; validation.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received. The authors declare that there was no financial relationship or grant support from external parties.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not applicable as authors collected and analyszed no new data in this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.