Management of patients with incurable colorectal cancer: a retrospective audit

Abstract

Aim

Counselling patients and their relatives about non-curative management options in colorectal cancer is difficult because of a paucity of published data. This study aims to determine outcomes in patients unsuitable for curative surgery and the rates of subsequent surgical intervention.

Method

This was an analysis of all colorectal cancers managed without curative surgery in a district general hospital from a prospectively maintained cancer registry between 2009 and 2016, as decided by a multidisciplinary team. Primary outcomes were overall survival and secondary outcomes were subsequent intervention rates and impact of tumour stage.

Results

In all, 183 patients out of 976 patients (18.8%) were identified. The median age at diagnosis was 81 years [interquartile range (IQR) 71–87 years]. Overall median survival from diagnosis was 205 days (IQR 60–532 days). One-year mortality was 62.3%. Patients were classified into two groups depending on the reason for a non-curable approach: patient-related (PR) or disease-related (DR). The difference in survival between PR (median 277 days, IQR 70–593) and DR (median 179 days, IQR 51–450) was 98 days (P = 0.023). Twenty-four patients were alive at the end of the study period; 19 out of 91 cases in PR (20.8%) and five out of 92 cases in DR (5.4%). Overall intervention rates were 11.9%, with higher rates in the DR group (P = 0.005). Disease stage was not associated with subsequent surgical intervention between the two groups (P = 0.392).

Conclusion

Life expectancy for non-curatively managed patients within our unit was 6.8 months with one in nine patients requiring subsequent surgical admission for palliation. This information may be useful when counselling patients with incurable colorectal malignancy.

What does this paper add to the literature?

The results of this study may assist in the appropriate counselling of patients with incurable colorectal malignancy.

Introduction

Surgical resection is the mainstay of curative treatment in the majority of patients with colorectal cancer. Successful outcomes are determined by both tumour (stage, grade and adverse histopathological features, e.g. nodal metastasis) and patient factors (comorbidity and responsiveness to adjuvant therapy). Not all patients are candidates for major curative surgery. Many factors, including patient choice, influence this decision. Currently there is a significant amount of published data to counsel patients on the outcomes of resectional surgery; however, comparatively little is known about the natural history of colorectal cancers in those unfit or unsuitable for curative resection. This lack of information adversely affects adequate counselling of these patients.

Recent legal precedents have emphasized the importance of providing patients with fully informed consent 1, 2. Clearly informed decision making in patients with and without curable disease necessitates adequate information.

The National Bowel Cancer Audit (NBOCA) in 2015 reported that one-third of cancers are not operated on owing to a combination of tumour stage and frailty. Of those undergoing surgery, 96% remain alive at 90 days but a fifth will have an unplanned readmission within that period 3. The 2-year survival rate is 91% in patients with Stage 1 disease who do not undergo surgery. This falls to 36% in the frail or those with extensive disease. Whilst 30-day mortality in patients over 80 receiving surgery is reportedly between 13% and 15%, 12% of this group are unable to return home postoperatively owing to increased care needs. Reaching the right decision for these patients to maximize quality of life is therefore essential 4.

The aim of this study was to review the outcomes of patients with incurable colorectal cancer and to determine their rates of emergency surgical intervention.

Methods

A retrospective audit of a prospective cancer registry database collected over an 8-year period in a single institution was undertaken. All patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer, at any age, managed without curative surgery as a first-line treatment due to frailty, disease factors, patient choice or any other reason were identified. Outcome measures comprised overall survival post-diagnosis and incidence of subsequent surgical or endoscopic intervention.

Patient selection

All patients of any age diagnosed with colorectal cancer from a single hospital trust between 2009 and 2016 recorded on the Somerset Cancer Record (SCR) were identified. Of these, any patient determined to be unsuitable for curative surgery as the primary intent, as documented at the multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT), was included. Prior to 2009, almost all MDT records were not stored on the electronic SCR and as such were not readily accessible or accurate so data were only collected from 2009 onwards.

While annual caseloads were not uniform within our unit, over the preceding 5 years the unit managed approximately 150 new diagnoses each year as recorded on the SCR, of which 20–30 were managed without curative intent. We performed a screening of our data prior to commencement to confirm sufficient numbers to permit exploratory analysis and further sub-group analyses.

Information extracted included demographics, site, TNM staging, age at diagnosis, age at death (where applicable), treatment modalities, survival (taken as time from diagnosis to death) and the predominant reason precluding curative surgery as judged by the MDT. Fitness for surgery was a clinical decision based on anaesthetics assessment via MDT; however, the ultimate decision lay with the operating surgeon. Where patients were alive at the end of the study period a fixed end-point (4 April 2017) was used and median survival was determined.

Patients were followed up using the SCR and cross-checked with electronic hospital systems for evidence of readmission and subsequent intervention including electronic patient letters, discharge summaries, pathology reports and imaging systems to ensure follow-up until April 2017.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was overall survival (1-year and overall) from diagnosis in patients with colorectal cancer deemed unsuitable for curative surgery at colorectal MDT. This was defined as follows: any patient with colorectal cancer who was felt at MDT to have disease that was unresectable due to advanced local disease or metastatic to an extent that precluded curative treatment; patient frailty associated with high risk of operative morbidity and mortality; or patient choice. Frailty was taken to be any patient deemed by the MDT to be unsafe for major surgery owing to comorbidity or poor performance status or a combination thereof. The concept of frailty remains an emerging and evolving surgical concept, and while a number of scoring systems are being increasingly used, these are not part of routine practice. The MDT routinely comprised five consultant colorectal surgeons, two consultant radiologists, a consultant histopathologist, two consultant oncologists, two colorectal nurse practitioners and the MDT coordinator.

Secondary outcomes were rates of subsequent intervention (defunctioning stoma, major resection with stoma, stent, chemotherapy or radiotherapy). These were re-classified for the purposes of analysis as either endoscopic/surgical or non-surgical with a particular focus on the former in this study. Rate of subsequent intervention was assessed against both the original reason for not proceeding with curative surgery and by stage of disease. For simplicity, TNM stages where available were converted to American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) Stages I–IV.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Kaplan–Meier survival analyses with log rank test (and Breslow test when required) were conducted to assess survival differences between groups. Comparison between groups regarding rate of intervention as well as the effect of disease stage were tested using Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test (if appropriate). The significance level was taken as a P value < 0.05. Where significance was identified, where appropriate, a post hoc analysis and a Bonferroni adjustment were performed to account for multiple testing.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not considered necessary as it was a retrospective cohort study from a prospectively maintained cancer registry (NBOCA) looking at outcomes in established clinical practice. There were no identifiable patient data.

Results

Demographics

Over the study period 976 patients were identified with colorectal cancer within our unit. Of these 184 (18.9%) patients were originally deemed unsuitable for curative surgery by the MDT. The male to female ratio was 1:0.9. Median age at diagnosis was 81 years [interquartile range (IQR) 71–87] with 104 (56.5%) patients aged 80 or over. Tumour location is shown for the non-curative cohort with data in Table 1. The distribution of cancers was as follows: 26.2% (48 cases) in the rectum, 16.4% (30 cases) in the sigmoid colon and 14.8% (27 cases) in the caecum. For comparison, Table 1 also displays the tumour distribution in patients offered curative resection. The spread of right-sided (tumours up to and including the splenic flexure) and left-sided tumours (descending colon to rectum) were comparatively similar across curative and non-curative groups (chi-squared, P = 0.860).

| Location | Non-curative cohort (n = 183) | PR group (n = 91) | DR group (n = 92) | Surgically managed cohort (n = 792) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | % | Cases | % | Cases | % | Cases | % | |

| Caecum | 27 | 14.8 | 11 | 11 | 16 | 17.4 | 125 | 15.8 |

| Ascending colon | 14 | 7.7 | 9 | 9.9 | 5 | 5.4 | 79 | 10 |

| Hepatic flexure | 10 | 5.5 | 3 | 3.3 | 7 | 7.6 | 29 | 3.7 |

| Transverse colon | 16 | 8.7 | 8 | 8.8 | 8 | 8.7 | 61 | 7.7 |

| Splenic flexure | 3 | 1.6 | 3 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 2.8 |

| Descending colon | 4 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 3.3 | 33 | 4.2 |

| Sigmoid | 30 | 16.4 | 13 | 14.3 | 17 | 18.5 | 186 | 23.5 |

| Recto-sigmoid | 16 | 8.7 | 6 | 6.6 | 10 | 10.9 | 32 | 4 |

| Rectum | 48 | 26.2 | 29 | 31.9 | 19 | 20.7 | 172 | 21.7 |

| Anal | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | 12 | 1.5 |

| Appendix | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | 12 | 1.5 |

| Small bowel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1.9 |

| Benign | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Location not specified | 13 | 7.1 | 8 | 8.8 | 5 | 5.4 | 12 | 1.5 |

Reasons precluding curative surgery were initially identified as extent of metastatic disease, 85 cases (46.2%); frailty, 78 cases (42.4%); patient choice, 11 cases (6.0%); locally advanced disease, five cases (2.7%); and other reasons, four cases (2.2%). Only two patients (1.1%) received non-curative surgery initially. One patient had palliative surgery at presentation, and one was admitted as an emergency which resulted in diagnostic laparotomy leading to subsequent palliation. The remaining patients were managed with active monitoring, stent, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or palliative care.

Those with frailty or patient choice as the main issue were grouped as patient-related (PR) factors, 91 cases (49.7%), while those with metastatic or unresectable disease were classed as disease-related (DR), with 92 cases (50.3%). Those falling under “other” were re-classified accordingly where possible (one patient was subsequently excluded owing to a concomitant brain tumour that delayed decisions on management of the colorectal cancer), leaving a total final cohort of 183 patients. Tumour stage at presentation was available for 83 cases in the PR group (91%) and 77 in the DR group (84%), as shown in Table 2. Unfortunately only 61 cases (33%) had recorded World Health Organization (WHO) performance statuses: 39 cases (43%) of the PR group and 22 cases (24%) of the DR group. This is also shown in Table 2, broken down by stage. Retrospective performance status assessment was not possible owing to missing information from MDT records. Where records were kept, the majority of patients in the PR group were placed in the more severe categories (Stages 3–4) whilst a larger majority of cases in the DR group were 0–2.

| Cases | % | Cases | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage (where available) | PR (n = 83) | DR (n = 77) | ||

| 1 | 20 | 24.1 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 2 | 13 | 15.7 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 3 | 26 | 31.3 | 6 | 7.8 |

| 4 | 24 | 28.9 | 69 | 89.6 |

| WHO performance status | PR (n = 39) | DR (n = 22) | ||

| 0 | 3 | 7.7 | 8 | 36.3 |

| 1 | 1 | 2.6 | 2 | 9.1 |

| 2 | 8 | 20.5 | 5 | 22.7 |

| 3 | 15 | 38.5 | 5 | 22.7 |

| 4 | 10 | 25.6 | 2 | 9.1 |

| 5 | 2 | 5.1 | 0 | 0 |

In those managed non-operatively in the first instance, 22 cases (12%) were subsequently admitted for emergency surgery owing either to acute obstruction or uncontrollable diarrhoea (21 patients had a stoma, one stent).

Outcome in patients with incurable disease

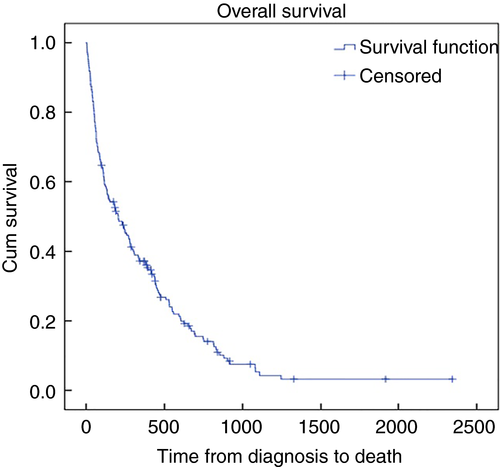

A total of 159 patients (86.9%) died within the study period with a 30-day mortality of 12.6% (20 cases) and 1-year mortality of 62.3% (99 cases). Overall median survival from diagnosis to death was 205 days (IQR 60–532). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for all patients at our colorectal unit who did not undergo curative surgical management is shown in Fig. 1.

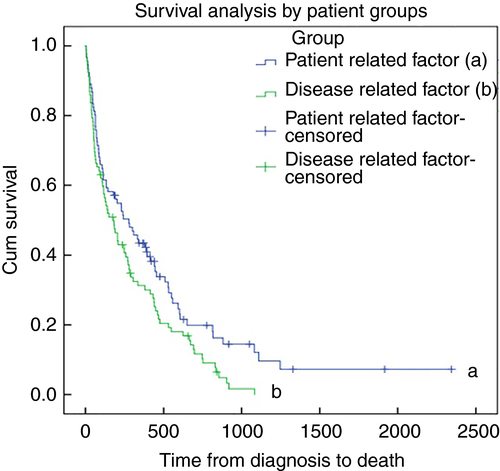

Outcomes broken down by sub-group are detailed in Table 3. The median survival in the PR group was 277 days (IQR 70–593) vs 179 days (IQR 51–450) in the DR group (P < 0.02, Fig. 2). However, as the survival curves only start to deviate beyond 250 days, a Breslow test was performed to further characterize this. The Breslow test was not statistically significant (P = 0.11). This is emphasized by the 1-year survival analysis that demonstrated a weak association between the two groups which did not reach statistical significance (log rank test P = 0.08). One-year survival probabilities for the PR and DR groups were 0.407 and 0.283 respectively.

| N = 183 | Patient-related | Disease-related | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91 | 92 | |||

| Dead 72 (79.1%) | Alive 19 (20.9%) | Dead 87 (94.6%) | Alive 5 (5.4%) | |

| Median survival (days) | 277 | 179 | ||

| Range (days) | 3–2345 | 6–1083 | ||

| Rate of readmission for surgical/endoscopic intervention | 6 (6.6%) | 16 (17.4%) | ||

| Tumour stage (1–4) in readmissions | n = 6 | n = 16 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2 | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 3 | 0 (0%) | 4 (25%) | ||

| 4 | 3 (50%) | 8 (50%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (25%) | ||

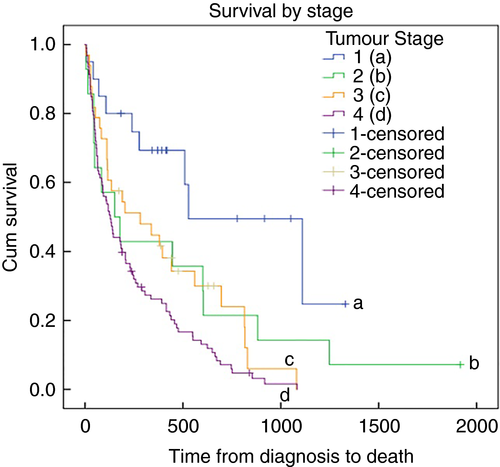

The relationship between tumour stage and survival was also assessed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, where staging was available (87.4%, 160 cases), and is illustrated in Fig. 3 (log rank test, P = 0.001). As expected, Stage 1 disease was associated with the longest survival while Stage 4 disease showed the worst outcomes. A comparison of Stage 2 and 3 disease, however, showed no statistical difference in outcomes (log rank test, P = 0.697) but this may be a consequence of incomplete data in these groups.

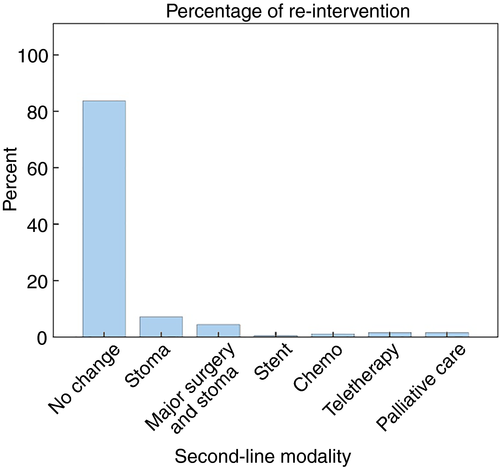

Effect of sub-group on rates of re-intervention

An analysis of rates of re-intervention (stent, defunctioning stoma, major surgery with stoma, chemotherapy and radiotherapy) demonstrated that in the majority of cases (153 cases, 83.6%) patients did not require a change from their original treatment modality (Fig. 4). Seven per cent of the cohort (13 cases) required a defunctioning stoma, 4.4% (eight cases) were readmitted for major surgery and stoma and 0.5% (one case) required a stent subsequently. In total, therefore, 12% (22 cases) of the cohort required some form of surgical or endoscopic re-intervention.

A comparison between the two groups demonstrated that patients within the DR group experienced a higher rate of surgical/endoscopic intervention vs those within the PR group, 17.4% (16 cases) and 6.6% (six cases) respectively, as shown in Table 4 (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.005). The median time to surgical/endoscopic intervention was 111 days in the DR group (range 25–621, n = 16) vs 125 days in the PR group (range 13–397, n = 6).

| Type of intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No secondary intervention | Surgical/endoscopic | Chemo/radio or palliative | |||

| Patient group | Patient-related factor | Count | 84 | 6 | 1 |

| % within group patient/disease oriented | 92.3% | 6.6% | 1.1% | ||

| Disease-related factor | Count | 69 | 16 | 7 | |

| % within group patient/disease oriented | 75.0% | 17.4% | 7.6% | ||

Effect of tumour stage on rate of re-intervention

Table 5 outlines the rate of re-intervention and type (surgical/endoscopic vs chemo/radiotherapy) across disease stages. There was no significant difference between the disease stage on rates of subsequent intervention (P = 0.392). Across those with Stages 2–4 disease rates ranged from 11.8% (11 out of 93) to 14.3% (two out of 14). However, it is worth noting that no Stage 1 tumour required subsequent re-intervention.

| Type of intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No secondary intervention | Surgical/endoscopic | Chemo/radio or palliative | |||

| Tumour stage | 1 | Count | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| % within tumour stage | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| 2 | Count | 12 | 2 | 0 | |

| % within tumour stage | 85.7% | 14.3% | 0.0% | ||

| 3 | Count | 26 | 4 | 3 | |

| % within tumour stage | 78.8% | 12.1% | 9.1% | ||

| 4 | Count | 78 | 11 | 4 | |

| % within tumour stage | 83.9% | 11.8% | 4.3% | ||

| Total | Count | 136 | 17 | 7 | |

| % within tumour stage | 85.0% | 10.6% | 4.4% | ||

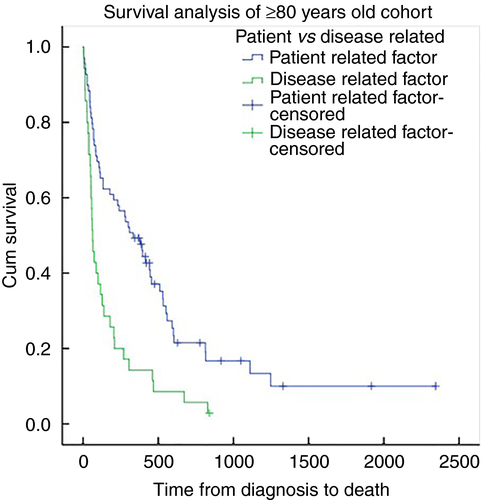

Comparison of outcomes in the all-ages cohort vs an elderly population

A separate analysis of PR vs DR outcomes was performed in patients aged 80 or over to compare outcomes in an elderly population. Overall 30-day and 1-year mortality in this cohort was 13.5% (14 cases) and 62.5% (65 cases) respectively, with a median overall survival of 178 days (IQR 52–529). Within groups, median survival was 334 days (IQR 74–602) for the PR group and 63 days (IQR 37–205) in the DR group (P = 0.001). Figure 5 demonstrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curve in this cohort.

Discussion

The results of this exploratory study into the natural history of incurable colorectal cancers suggest that approximately two-thirds of patients were still alive at 1 year, with a median survival of 6.8 months. Overall survival was longer in those with PR obstacles to surgery compared to those with metastatic or unresectable disease. One in nine patients required subsequent intervention, with a higher prevalence in those unable to have surgery owing to intrinsic DR factors. Unexpectedly, whilst disease stage influenced survival it did not influence the frequency of readmission.

The anatomical distribution of tumours in this study is consistent with the published literature. Our results demonstrated an almost even split between men and women 4, 5.

Initially we identified five main reasons that precluded curative surgery. These included frailty, patient choice, extent of metastatic disease, unresectable disease and miscellaneous. This accords closely with work by Tweedle et al. in 2012 6. Most of our patients were incurable on grounds of frailty or metastatic disease. Smaller numbers encompassed the remaining categories making a meaningful analysis between groups unlikely. An alternative classification was therefore adopted whereby obstacles to curative surgery were simply based on the patient or the disease process itself.

Overall survival was better in the PR group; however, this was only apparent at 1-year post-diagnosis. Within the first year there was no difference in survival (P = 0.11), the reason for which is unclear. The overall survival difference, however, is likely to reflect the adverse effect of advanced tumour burden on physiological reserve within the DR group. In the elderly subset (age ≥ 80) survival was also significantly longer in the PR group vs DR group with a clear survival advantage early in the curve (P = 0.001). PR group survival was greater in the elderly cohort vs the main PR group yet DR survival was lower in the elderly DR group vs the main DR group. A possible explanation for this is that there is a synergistic impact of poor age-related physiological reserve with advanced disease burden. Bethune et al. reported outcomes in 39 patients over the age of 80 with non-metastatic colorectal cancer, excluded from surgical treatment owing to frailty 4. Nine patients died within 45 days of diagnosis, a further five at 36 months, with a mean survival of 1 year and 176 days compared to 178 days in our ≥ 80 cohort. Harris et al. also compared outcomes in an octogenarian cohort of 292 patients of whom 141 underwent a formal resection and 15 a local resection; 136 were managed non-operatively. One-year mortality in their non-operative group was found to be 69.1% (vs 21.8% managed surgically) (P < 0.001) 7.

Thirty-day and 1-year mortality in our study were comparable with Harris et al. while our shorter overall survival of 6.8 months was similar to the survival reported by Hall and Williams 8. Where Bethune and Harris focused on octagenarians, this study included all ages as it reflected the heterogeneity of patients presenting to our fast track clinics. Tweedle et al. described outcomes in 116 patients across a comparable age range (27–95 years) with survival times ranging between 14 and 41 weeks where metastases were present compared to an average of 80 weeks (42–124) with local disease only 6.

Analysis of the 160 patients in whom staging information was available (87.4%) confirms that staging does determine survival 9, 10. Interestingly, while a clear difference was noted when comparing Stages 1 and 4 disease, no statistical difference in survival was seen between Stages 2 and 3 disease. This suggests that more aggressive treatment in patients with Stage 3 disease may be appropriate. This is supported by data from Akbar et al. who showed survival benefit across all stages through excisional surgery even in those with Dukes C disease 11.

Whilst 83.6% of patients treated without curative resection required no subsequent readmission, 11.9% of patients experienced tumour-related complications at some stage requiring a surgical intervention. This accords with the published literature which reports tumour-specific complications ranging between 8% and 16% 12-14. In contrast, Tweedle et al. reported 29% of their study cohort requiring treatment for obstruction while Turner et al. found 68 out of 156 (44%) needed operative intervention 6, 15. In the latter study, 28% of those were performed electively while 16% were emergency presentations.

When stratified into PR and DR groups, the latter experienced a higher rate of surgical or endoscopic re-intervention (17.4% vs 6.6% in the former group) as well as a shorter time to intervention (111 days in DR vs 125 in PR). This is not surprising as one might ordinarily expect advanced disease to cause obstruction or intolerable symptoms more frequently and quickly than earlier stages of disease 12. However, in this study, while patients with Stage 1 disease had no readmissions, cancer stage as a whole demonstrated no statistical impact on rate of intervention (P = 0.392). We therefore conclude that, while a patient's stage was not predictive of readmission, the probability of successfully managing a patient out of hospital without subsequent intervention appears greater in the PR group.

Only one patient in this cohort was stented during the study period. This probably represents the reduced availability of a stenting service within our semi-rural unit during emergency on-call hours. A defunctioning stoma remains a common option in many units as it can be readily performed in a timely fashion by the surgical team 16.

Counselling and consent

Over half of patients within our cohort were aged over 80. In an ageing population, the incidence and frequency of comorbid conditions increases with age and, with it, the probability of being deemed unsuitable for curative surgery. Informed consent in modern practice requires that patients be given not just their best management option but all options, including the outcomes of conservative approaches. This underlines the importance of understanding the natural history of the disease in those whose fitness for surgery is in doubt. It allows for more informed discussions about the risks and benefits of operating vs non-intervention. This is especially relevant in the light of the 2015 Montgomery ruling in the UK Supreme Court which emphasizes the importance of fully informed consent 2.

The 2017 “Getting It Right First Time–General Surgery” document discussed an increasing prevalence of metastatic colorectal cancer patients not being offered surgical resection even in specific cases which current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines may suggest are potentially beneficial. The report observed that surgeons, whose performances are solely measured by mortality and national audit data (without taking into context the individual risk profile for a patient or their individual circumstances), might in some cases feel reservations about offering such patients high-risk procedures during counselling. However, as the Montgomery ruling stipulates, patients will need an understanding of the risks and benefits of not acting, including the risk of complications, symptoms and readmission for palliative surgery as an emergency. In such cases a patient may well wish elective surgery even with elevated risk if given the option and accurate risk assessment 2, 17.

Study limitations

This cohort study was a retrospective analysis from a prospectively maintained cancer registry. There was some heterogeneity in the quality of historical data recorded. Incomplete staging data were more prevalent in the DR than PR groups (15 vs 8 cases respectively). Furthermore, WHO performance status was only available for 61 out of 183 patients (33.3%), while incomplete MDT records precluded retrospective calculation for the remainder. This precluded a quantifiable analysis of frailty and introduces a risk of bias in comparison of groups. Additionally, we accept that larger studies may be required to confirm our findings.

The data presented in this single-centre study come from a semi-rural unit with a more advanced age demographic and inevitably some comparative differences in socio-economic circumstances with other units. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to other units.

A robust system was not in place for large scale data acquisition of cause-of-death data within our unit preventing evaluation of overall survival vs cancer-specific survival. Finally, routine cancer genetics is a recent addition within our unit and may influence decision making in the future. Future work in this group of patients needs to focus on quantifying frailty and performance status. Increasing life expectancy will continue to pose significant challenges to the surgeon looking after patients with colorectal malignancy.

Conclusions

In this study, the overall life expectancy following diagnosis was approximately 7.3 months and one in nine patients required subsequent admission for surgical or endoscopic measures to manage symptoms. The present study adds valuable evidence to the relatively sparse formal literature on outcomes in colorectal cancer for those unsuitable for a curative surgical intervention. This information may assist in the counselling of patients and their relatives prior to making treatment decisions.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.