Developing and assessing a cadaveric training model for transanal total mesorectal excision: initial experience in the UK and USA

Abstract

Aim

Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) has become one of the most promising technical advancements in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer, with rising numbers of surgeons seeking training. We describe our experience with human cadaveric courses for taTME delivered in two countries.

Method

Four fresh human cadaveric workshops conducted in Oxford, UK, in 2015 and two in Chicago, USA, in 2013−2014, trained a total of 52 surgeons. Parameters of operative performance for each delegate were recorded. Previous surgical experience and uptake of taTME in the surgeons’ clinical setting were surveyed.

Results

Forty-seven taTME cases were performed on cadaveric models. Participating surgeons had previous experience in laparoscopic TME surgery and transanal approaches but limited taTME exposure. The purse-string remained occluded throughout in 93% of UK and 60% of US cases. Operative timings for key procedural steps were similar between the two countries with a mean time from start of circumferential dissection to peritoneal entry of 79.5 min (range 25–155). 96% of surgeons dissected transanally to a level S2 or above. The TME specimen quality was complete or near complete in 81%, with improvements noted between the first and second procedure performed. 81% of surgeons surveyed are currently performing taTME in their local hospitals.

Conclusion

Fresh-frozen cadavers provide excellent teaching models for complex pelvic surgery. A structured training curriculum including reading material, dry-lab purse-string practice and postcourse mentorship will provide surgeons with a more complete training package and ongoing support, to ultimately ensure the safe introduction of taTME in the clinical setting.

What does this paper add to the literature?

This is the first paper to report on the development and evaluation of human cadaveric training courses for transanal total mesorectal excision in two different countries. We discuss the benefits and challenges of this training model, which is intended to be a useful guide to others organizing similar courses.

Introduction

Transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME) is a novel approach pioneered to tackle difficult pelvic dissections, especially in obese men with a narrow pelvis. The aim of this approach in low rectal cancer is to optimize oncological outcomes by obtaining a complete TME specimen with negative margins. A more accurate pelvic dissection will also help to avoid injury to valuable surrounding structures, in particular the neurovascular bundles that control bowel, urinary and sexual function. The evolution of the technique required extensive preliminary work in animal laboratories 1, 2 and on human cadavers 3-5 in order to demonstrate feasibility of the concept and establish the critical steps of the operation. In 2010, the first human clinical case was reported by Sylla et al. 6 and subsequent phase I clinical trials were performed with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval 7-9. Based on this experience, in-depth knowledge of anatomy and advanced surgical skills were identified as prerequisites to performing taTME.

The development of training models and workshops is therefore crucial, as they provide dedicated education and hands-on experience in order to ensure the safe introduction of taTME into the clinical setting. The intricate human pelvic anatomy is difficult to reproduce accurately in bench-top and virtual reality models. The anatomy also varies substantially compared to other mammals, some of which lack a mesorectum. Fresh-frozen cadavers therefore offer the most useful training model with precise anatomical structures and more ‘life-like’ tissue handling properties with visual and tactile feedback. The use of human cadavers is the preferred model for training in laparoscopic colorectal surgery 10 and has also been shown to enhance delegates’ performance and shorten their learning curve, as demonstrated in the English Low Rectal Cancer (LOREC) National Development Programme 11. Furthermore, operating with a two-team approach simultaneously, laparoscopic and transanal, allows resection of longer colonic specimens, reduces the risk of injury to the proximal colon as well as potentially reducing operative time 4, 5, 12.

The aim of this paper is to report the development of human cadaveric training workshops for taTME delivered in Oxford in the UK and in Chicago in the USA. We also aim to evaluate the courses and propose a training pathway for new learners of taTME.

Methods

The lead clinicians designed the curriculum for the taTME courses, based on their extensive experience with taTME, both clinically and in cadaveric models. The programme was delivered in established cadaveric training facilities in Chicago in the USA and in the University of Oxford, Department of Anatomy, in the UK. Two training laboratories were hosted in the USA over a 10-month period between September 2013 and July 2014, representing the first taTME training laboratory in the USA. Each course trained five teams of two colorectal surgeons making a total of 20 surgeons. In the UK, four courses were taught between January and September 2015 for a total of 32 delegates (eight per course).

Training programme and cadaveric models

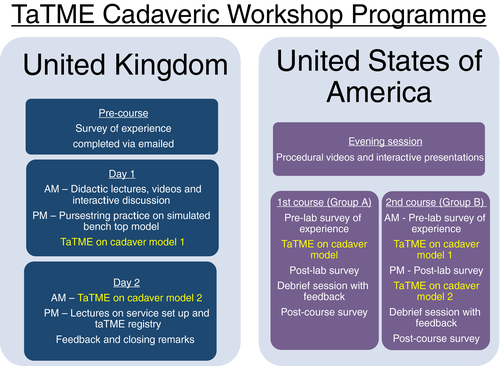

A combination of teaching methods was employed during the workshops, including interactive presentations, videos, dry-lab sessions and cadaveric dissection (Figs 1 and 2). The didactic sessions explained the rationale for taTME, up-to-date literature findings as well as describing each technical step of the operation. During the hands-on cadaveric laboratory, delegates worked in pairs to perform taTME following the surgical principles and procedural steps taught during the preceding lecture.

On the American courses, each team performed taTME with the transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) platform in one cadaver (group A) or two consecutive cadavers on the same day (group B), for a total of 15 procedures. During the first workshop both male and female cadavers were utilized, while teams only operated on male cadavers for the second course. Although training in both male and female cadavers is preferred, due to budgetary constraints related to high costs and availability of cadavers priority was to provide training in male cadavers in which dissection can be more arduous especially with regard to the anterior plane.

On the British course, a session was dedicated to practising the rectal purse-string suture on both dry models and simulated models with cadaveric bowel specimens (Fig. 2). Surgeons then moved on to operating in pairs on the full cadaver, one cadaver per pair on each of two consecutive days. 91% (29/32) of cadavers were male, based on the availability of cadavers at the time of the courses.

Fresh-frozen cadaveric models were used for all courses, frozen within a week of procurement and then thawed at room temperature approximately 3 days prior to the workshop. Models requested were preferentially male and had not undergone any abdominal or pelvic surgery. Each operating station replicated the operating theatre set-up including electric operating tables, two laparoscopic towers and monitors ergonomically positioned for combined abdominal and transanal access, energy, suction stations and dissection equipment. Cadaver workshop laboratories were sponsored by industry.

Delegates

In the USA, course attendance for the taTME cadaver laboratories was by invitation only. Invited participants primarily consisted of colorectal surgeons with extensive experience in laparoscopic and/or robotic TME, intersphincteric resection, transanal endoscopic surgery [TEM, transanal endoscopic operation (TEO) or transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS)] and postgraduate education. In the UK, the workshop was advertised on the LOREC website and at national conferences. Places on the course were open to consultant colorectal surgeons working both nationally and abroad with an interest in developing a taTME service in their local hospital. Prior to attending the course, all delegates completed a questionnaire detailing their level of experience in performing various transanal procedures such as TEM and TAMIS. The number of taTME cases that each delegate had previously participated in as observer, assistant or primary surgeon was also recorded. In addition, they were asked to reflect upon their personal goals and what they intended to achieve from the course.

Trainers

In the UK, the workshops were planned and delivered by a multidisciplinary faculty including an international group of colorectal surgeons with expertise in taTME, anatomists and a theatre sister experienced in the operating room set-up and nursing requirements during the procedure. The surgeon trainers in the USA had over 5 years’ experience of conceptualizing and developing the technique in animal models and human cadavers. Trainers in the UK had attended cadaveric training, observed live cases and were involved in international meetings discussing early adoption and evolution of taTME. All trainers had extensive experience in laparoscopic TME (> 200 cases) and minimally invasive transanal approaches including TEM and TAMIS. They had performed between 10 and 20 live cases before teaching on the cadaver courses. In addition, the trainers had received teaching skills training including the ‘Train the Trainers’ course. It was intended that the workshop would facilitate the establishment of links between delegates and local experts who could then offer proctorship and further advice when the delegate performed their first live cases. An extensive faculty was assembled in order to provide a high ratio of trainers to delegates (1:2) at all of the workshops. Individual feedback and tailored supervision was then possible for each participant. In the USA, because these were the first taTME training laboratories aimed at training colorectal experts and future taTME proctors, this was not the case. The curriculum of the taTME courses was designed and delivered by two taTME proctors with extensive experience with taTME, both clinically and in cadavers.

Operative performance

Procedural steps were timed and video-recorded during the operation and included

- laparoscopic access;

- purse-string occlusion of the rectum and TEM platform insertion;

- distal rectum transection at the level of the dentate line;

- taTME with anterior peritoneal entry;

- completion of the TME using a combined transanal and laparoscopic approach.

The training workshop was evaluated through timing of the delegates’ performance of each procedural step and evaluating the technical quality of the rectal purse-string and stapled anastomosis. Specimens were extracted either transanally or transabdominally, photographed and TME quality was graded by two proctors as either complete, near complete or incomplete as described by Quirke et al. 13.

Course evaluation: impact of the workshop

The impact of the workshop on delegates’ practice in their local hospitals was surveyed via questionnaires emailed to the surgeons between 3 and 6 months following their attendance at the course.

Data presentation and analysis

Data from questionnaires on previous surgical experience are presented as a percentage or mean with range in parentheses where appropriate. Procedural timings are shown as the mean and median in minutes with the range in parentheses. The quality of the purse-string and TME quality are recorded as number of cases and percentages.

Results

A total of 47 cadaveric dissections were performed during the six reported workshops in the UK and USA. The majority of human cadavers (85%; 29/32 in the UK, 11/15 in the USA) were male with a mean body mass index of 26.6 kg/m2 (range 18.6–37.8). All cases performed in the UK used the GelPOINT Path transanal access platform (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, California, USA) whilst the TEM platform (Richard Wolf, Vernon Hills, Illinois, USA) was utilized in the USA.

Delegates

A total of 20 colorectal surgeons attended the American cadaveric workshops split between two training days in September 2013 and July 2014. Delegates had on average 15.6 years’ (range 2–28) experience in pelvic surgery, and all of them independently performed minimally invasive rectal surgery with a mean of 39 cases per year (range 13–75). All participants had extensive TEM and/or TAMIS experience with a mean volume of 24 cases per year (range 5−50). Only four surgeons (20%) had performed taTME (mean 10 patients, range 2–22) prior to the course for benign and malignant indications.

In the UK, 32 colorectal surgeons attended the workshops, with a mean number of 9 years’ experience (range 0.5–20) in practising rectal surgery. Most surgeons had at least some experience in minimally invasive rectal surgery with more than 50% of delegates having performed TEM, TEO or TAMIS. 53% of surgeons had previously performed more than 200 laparoscopic colorectal resections with a mean of 51 independent laparoscopic TME procedures. Half of the participants had no experience in taTME. Six delegates had previously observed on average five cases, and 10 respondents (31%) had performed taTME in an average of four patients (range 1–11).

Operative performance

The time taken to perform key steps of the procedure was recorded for each delegate and is outlined in Table 1. The time taken to complete the purse-string suture at the start of the taTME procedure was similar between the American and British groups, with a mean of 12.5 min (range 4–25 min). However, 93% of purse-strings remained occluded throughout the case in the UK group compared to 60% in the American group. A mean time of 79.5 min (range 25–155) to complete the TME dissection from start of circumferential dissection to peritoneal entry was similar for the two groups. In the US laboratories there were two instances of superficial dissection into the prostate, recognized and the dissection plane successfully corrected. During the UK course, half of one prostate was mobilized before being identified and corrected. There were no urethral injuries during the courses. The estimated level of dissection attained by the transanal approach was beyond S2 in 96% of cases.

| UKa | USA | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to perform purse-string (min) | ||

| Mean | 13 | 12 |

| Median | 15 | 10 |

| Range | 4–25 | 4–25 |

| Purse-string remained occluded throughout case? | ||

| Yes (%) | 27 (93) | 9 (60) |

| No (%) | 2 (7) | 6 (40) |

| Set up of transanal platform (min) | GelPOINT | TEM |

| Mean | 15 | 13 |

| Median | 15 | 13 |

| Range | 5–35 | 5–24 |

| Time to enter presacral plane from start of circumferential transection (min) | ||

| Mean | 18 | 16 |

| Median | 17 | 14 |

| Range | 2–55 | 5–35 |

| Time from start of circumferential dissection to peritoneal entry (min) | ||

| Mean | 71 | 88 |

| Median | 75 | 90 |

| Range | 35–120 | 41–155 |

| Estimated sacral level of dissection attained from below (%) | ||

| L5−S1 | 11 (40) | 3 (20) |

| S2–S3 | 14 (52) | 10 (67) |

| S4–S5 | 1 (4) | 2 (13) |

| Other | Iliac (4) | − |

- a Results obtained from 29/32 cadaveric cases as one cadaver had a previous anterior resection and two had missing evaluation forms.

Data assessing the stapled anastomotic technique were collected during the UK courses on 23 cases. Results showed a mean time of 20 min (range 10–40) to create an end-to-end stapled anastomosis using a 28–31 mm circular stapling device. The anastomosis was intact in 78% of cases but required further interrupted sutures in five cases.

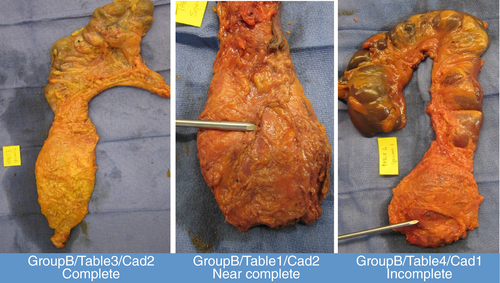

Quality of TME specimen

In the UK group, the TME quality of 21/32 specimens was assessed. The remaining cases were either not assessed or recorded, had missing evaluation forms or in one case the patient had already undergone a previous anterior resection. In the evaluated specimens, the TME was complete in 10 cases, near complete in eight cases and incomplete in three cases (Table 2).

| UK (%) | USA (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade of TME quality | ||

| 1 (incomplete) | 3 (14) | 4 (27) |

| 2 (nearly complete) | 8 (38) | 7 (46 |

| 3 (complete) | 10 (48) | 4 (27) |

In the US group, TME quality was graded as complete in 4/15, nearly complete in 7/15 and incomplete in 4/15 cases. Among group B who performed taTME in two consecutive cadavers on the same day, 4/5 teams performed taTME in female cadavers first, achieving near complete or complete TME in all cases (Table 3). The same four teams subsequently replicated near complete or complete TME in all four male cadavers (Fig. 3). The group B team that performed taTME in two consecutive male cadavers had an incomplete first specimen but obtained a complete TME on their second case. Among the five group A teams that performed taTME in a single male cadaver, 3/5 achieved an incomplete TME and 2/5 achieved a near complete TME.

| Group B team | First taTME, gender | First taTME, TME quality | Second taTME, gender | Second taTME, TME quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Female | 3 | Male | 2 |

| B2 | Female | 2 | Male | 2 |

| B3 | Female | 3 | Male | 3 |

| B4 | Male | 1 | Male | 3 |

| B5 | Female | 2 | Male | 2 |

Impact of the workshop

Following the two taTME courses in the USA, all 20 surgeons completed the post-course survey exploring their taTME practice. To date, nine out of the 10 teams with 18 colorectal surgeons are currently performing taTME clinically. These teams have performed a total of 85 taTME cases over a 2-year period. On average, each team performed nine taTME cases each (range 2–30) including 70 low anterior resections, three abdominoperineal excisions and 12 completion proctectomies. The indication for surgery was rectal adenocarcinoma in 62 cases (73%) and benign disease in 23 (27%). Most cases were performed by two surgeons either simultaneously or sequentially in 15 and 42 cases respectively. The remaining 28 cases were completed by a single surgeon performing both abdominal and transanal dissection sequentially.

Intra-operative problems reported during the clinical taTME cases included difficulties maintaining adequate insufflation to create a pneumorectum/pneumopelvis and identification of the correct dissection plane, particularly at the start of the TME dissection. In two cases, difficulty identifying the correct plane resulted in conversion to laparoscopic TME (2.3%), whilst in one other case involving a low anterior rectal tumour, taTME was complicated by a prostatic urethral injury which was recognized and repaired immediately (1.2%). All surgeons reported that they needed additional clinical practice to overcome their learning curve and that proctoring would be very beneficial.

Following the taTME workshops attended in the UK, 23/32 (72%) surgeons have completed the post-course survey exploring the uptake of the procedure in their local hospitals. Seventeen of these 23 surgeons (74%) have adopted taTME and performed a total of 68 cases (range 1–15). The indication for surgery was cancer and benign pathology in 49 (72%) and 19 (28%) cases respectively. 55% of cases were performed using a two-team approach either sequentially or simultaneously in 36% and 19% respectively. A single team switching between abdominal and transanal phases performed the remaining 45% of cases. Difficulty in identifying the correct dissection plane and an unstable pneumorectum were the most frequently encountered challenges intra-operatively. Four cases of unplanned incursion into the mesorectum and rectum also occurred, one urethral injury and one taTME case was aborted due to a suspected urethral injury. The remaining six surgeons were in the process of establishing a business case for taTME and found access to specialized taTME equipment and funding to be the greatest barriers to setting up the service. All respondents felt that proctoring of clinical cases would be greatly beneficial and welcomed further communication and guidance.

Discussion

Surgery is a lifelong apprenticeship, with education and training forming an important part of a surgeon's continuing professional development. Each new technique necessitates its own specific surgical skills set and in many cases adds a layer of complexity that must be understood and learnt. Relying solely on self-taught surgical modules is known to have a much longer learning curve and runs the risk of developing ‘bad habits’, which consequently slow down the uptake of a technique 14. Due to the complexity of the human pelvis, dry-lab models are not adequate, thus making human cadavers the best training models available 10. The main drawbacks of using cadaveric models are their unpredictable supply and cost to obtain, store and appropriately dispose of. Nonetheless, the cadaveric workshops provided very valuable educational information and positive feedback from delegates.

Key procedural steps for taTME revealed similar operative timings between courses. Although the number of cases is small, it is interesting to note that 93% of rectal purse-strings applied at the start of the taTME cadaveric dissection in the UK remained occluded compared to only 60% in the USA. One explanation may be due to the skills learnt during the sessions dedicated to purse-string application on bench-top models prior to proceeding with the cadaveric dissection in the UK. Delegates had access to these dry models throughout the course. This reinforces the need for simulated training to allow repetitive practice of key skills to shorten the learning curve and improve technical ability. Furthermore, group B in the American course operated on two consecutive cadavers on the same day. It is encouraging to see that the overall TME grading of specimens improved from the first to the second case with complete or near complete and no incomplete TME specimens. These results were obtained despite operating on more difficult male cadavers as opposed to females. Results from the UK group did not show any difference in the TME specimen quality between the 2 days. However, the key message is to provide ongoing practice and immediate feedback on consecutive mentored cases in order to build the surgeon's understanding, confidence and technical skill.

Following the course, most delegates successfully transitioned to performing taTME in their local hospitals. Amongst the British surgeons who had not yet started performing taTME in clinical practice, access and funding of specialized equipment were reported as the most frequently encountered barriers. Difficulty in allocating two surgeons to the same operating list in order to perform a synchronous taTME operation was also reported. Similar barriers are faced by US surgeons who commented that, while they were eager to replicate a two-team approach, staffing and billing constraints limited them to perform procedures as a single team, or to only use a second surgeon during the critical portion of the case, i.e. TME completion and specimen extraction. As the body of evidence supporting the safety of taTME grows and adoption of the technique becomes more widespread, these barriers will, it is hoped, be easier to overcome.

As one may expect, intra-operative challenges were encountered during the early stages of the surgeons’ experience when adopting taTME into their clinical practice. All participants reported difficulties in identifying the correct dissection plane at some point of the operation. Two cases required conversion to laparoscopic TME due to the uncertainty of the dissection plane. A third case of conversion also occurred following the suspicion of a urethral injury whilst one confirmed prostatic urethral injury and unplanned incursions into the mesorectum and rectum were also reported. Participants commented that, although the workshops were very useful, a period of proctorship during the start of their clinical taTME practice would be desirable. Further cadaveric training, although expensive and logistically difficult, may also be required if a proctor does not feel the training surgeon is ready for live cases or in a situation where a proctor may be logistically unavailable. While proctoring would be optimal, in the USA this may be more difficult to organize due to financial constraints, medico-legal issues and the need for local credentialling at each hospital the mentor attends.

Limitations of the data presented include TME specimens assessed by surgeons rather than histopathologists, missing data and a small caseload. Cadaveric TME specimen quality in particular can be more difficult to assess than live tissue, appearing more leathery or stiff. Although the use of different platforms and different course formats may limit the comparability of results, variation between the US and UK courses provides valuable lessons on how to improve each course further. For example, initial purse-string practice on simulators in the UK is likely to have contributed to the higher rate of complete stable purse-strings during the cadaveric procedure, whereas data collection was more complete in the USA with no missing evaluation forms.

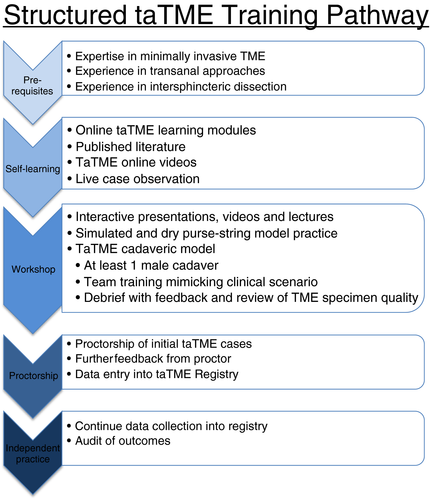

The experience and findings from the cadaveric workshops reported in this article are in agreement with the training pathway outlined in McLemore et al.'s recently published paper 9. The article lists six key elements that should be acknowledged and emphasized in the process of taTME training and implementation of the technique into surgical practice: (1) expertise in TME for rectal cancer; (2) expertise in minimally invasive (laparoscopic and/or robotic) TME from the abdominal approach; (3) expertise in transanal endoscopic surgery; (4) experience in intersphincteric dissection for very low rectal invasive neoplasms; (5) practice in taTME techniques in human cadaver models; and (6) IRB approved data collection with publication of outcomes and/or participation in a clinical registry. Furthermore, by running taTME workshops we have learnt the importance of team training with two surgeons and their scrub team, simulated purse-string practice prior to cadaveric work, the preferential use of male cadavers, immediate expert feedback and assessment of TME quality.

A recent international taTME educational collaborative has also been established following the first consensus meeting in October 2015 in the UK 15. The aims of the collaborative are to provide a shared communication platform to facilitate discussion and agreement on the essential elements of the optimal training curriculum for taTME and provide guidance on the implementation and assessment of the training programme. Based on previous experience, strengthened by the results and feedback from the cadaveric workshops described, we also embrace the need for a dedicated training curriculum. Figure 4 outlines a proposed training pathway that incorporates models available for pelvic surgery training, allows repeated practice of the purse-string (an essential step of the operation) and ensures continuous support for surgeons throughout their learning curve.

Standardization of the taTME technique, which is awaiting publication following the Delphi process carried out in preparation for the COLOR III trial 16, will further help provide a framework for future taTME training. Surgical innovation is flourishing and many surgeons are keen to learn more advanced and challenging techniques. However, our patients’ safety is paramount, and thus effective supervised training is critical.

Acknowledgements

taTME cadaver courses in the USA received financial support from Richard Wolf Medical Instruments (Vernon Hills, Illinois, USA). Cadaver courses in the UK received financial support from SurgiQuest (Milford, Connecticut, USA), Karl Storz (Tuttlingen, Germany), Applied Medical (Rancho Santa Margarita, California, USA), Lawmed (Hersham, Surrey, UK), Medtronic-Covidien (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).