A comparison of tumour and host prognostic factors in screen-detected vs nonscreen-detected colorectal cancer: a contemporaneous study

Abstract

Aim

In addition to TNM stage there are adverse tumour and host factors, such as venous invasion and the presence of an elevated systemic inflammatory response (SIR), that influence the outcome in colorectal cancer. The present study aimed to examine how these factors varied in screen-detected (SD) and nonscreen-detected (NSD) tumours.

Method

Prospectively maintained databases of the prevalence round of a biennial population faecal occult blood test screening programme and a regional cancer audit database were analysed. Interval cancers (INT) were defined as cancers identified within 2 years of a negative screening test.

Results

Of the 395 097 people invited, 204 535 (52%) responded, 6159 (3%) tested positive and 421 (9%) had cancer detected. A further 708 NSD patients were identified [468 (65%) nonresponders, 182 (25%) INT cancers and 58 (10%) who did not attend or did not have cancer diagnosed at colonoscopy]. Comparing SD and NSD patients, SD patients were more likely to be male, and have a tumour with a lower TNM stage (both P < 0.05). On stage-by-stage analysis, SD patients had less evidence of an elevated SIR (P < 0.05). Both the presence of venous invasion (P = 0.761) and an elevated SIR (P = 0.059) were similar in those with INT cancers and in those that arose in nonresponders.

Conclusion

Independent of TNM stage, SD tumours have more favourable host prognostic factors than NSD tumours. There is no evidence that INT cancers are biologically more aggressive than those that develop in the rest of the population and are hence likely to be due to limitations of screening in its current format.

What does this paper add to the literature?

In addition to having tumours of an earlier stage, patients with tumours detected through the FOBt screening programme have improved host prognostic factors, in terms of a lower preoperative systemic inflammation response, than patients with nonscreen-detected disease.

Introduction

The outcome following a diagnosis of colorectal cancer is directly related to the stage at diagnosis, with over 90% of those who undergo resection for Stage I disease being alive at 5 years compared with less than 50% for Stage III disease 1. Independent of the TNM stage, however, there are other additional adverse features of the tumour itself and the patient, the so-called ‘host’, that have been shown to predict a worse outcome. For example, the presence of venous invasion or poor differentiation are now used in clinical practice to help identify patients with more aggressive Stage II disease who are at a higher risk and hence may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy 2-4. It has been argued recently that the combination of T-stage and venous invasion is superior to the traditional TNM stage in predicting outcome in node-negative disease 5.

There is now a wealth of evidence that the presence of an elevated host systemic inflammatory response (SIR) is an independent negative prognostic factor in patients with cancer 6. The SIR can be assessed routinely with standard bedside tests such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) 7-11. In the specific case of colorectal cancer, those with an elevated preoperative SIR have a poorer outcome independent of the TNM stage 7, 12.

Screening for colorectal cancer using the guaiac-based faecal occult blood test (gFOBt) increases the number of early stage cancers diagnosed and reduces cancer-specific mortality 13-15. In addition, there is increasing evidence that screening using the faecal immunochemical test (FIT) may have improved sensitivity over gFOBt 16-18. This has led to the development of the Scottish Bowel Screening Programme (SBoSP), which is a combined gFOBt/FIT population-based screening programme 19. This has been found to detect a large number of early stage tumours, although interval cancers (tumours that develop within 2 years of a negative screening test) do develop 20.

In assessing the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening, previous work has examined differences between screen-detected and nonscreen-detected disease and has shown improved survival in patients with screen-detected disease 21-27. Such analysis has, however, focused on the stage and site of tumours, and only one such study has included detailed analysis of adverse tumour factors beyond TNM stage that are of independent prognostic significance 21. Furthermore, to date, no studies have included assessment of the preoperative host SIR within the context of a colorectal cancer screening programme. The aim of the present study was to examine the efficacy of the first round of a population-based gFOBt/FIT colorectal cancer screening programme in our geographical area with regard to cancer detection rates, and to compare and contrast adverse tumour and host prognostic factors in screen-detected and nonscreen-detected colorectal cancer.

Method

Details of all individuals who were invited to the first round of the SBoSP from April 2009 to the end of March 2011 in NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHS GG&C) were extracted from the prospectively maintained NHS GG&C Bowel Screening IT System (original date of extraction January 2012, updated April 2014). They included all individuals in NHS GGG&C aged between 50 and 74 years who were registered with a general practitioner. Methodological data on the screening algorithm used and processing of samples in the SBoSP have been described previously 19. Briefly, individuals are sent a preinvitation letter and then a gFOBt kit (hema-screen, Immunostics, Ocean, New Jersey, USA, supplied by Alpha Laboratories, Eastleigh, Hampshire, UK) and referred for colonoscopy if this is returned and is strongly positive (five or more of six windows positive). In the case of a weakly positive gFOBt (one to four of six windows positive) or a spoiled or untestable kit a confirmatory FIT kit (hema-screen SPECIFIC, Immunostics, Ocean, New Jersey, USA, supplied by Alpha Laboratories, Eastleigh, Hampshire, UK) is sent. Data were extracted on individuals invited for screening, including the combined gFOBt/FIT result and the uptake and result of colonoscopy.

All individuals invited for screening in this first round were cross-referenced with the prospectively maintained West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network (MCN) dataset and also linked to the Scottish Cancer Registry (SMR06). This allowed the identification of any patient with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. As screening invitations were biennial, patients with cancer detected more than 720 days after invitation to screening were excluded. Patients with colorectal cancer were then categorized as having screen-detected disease (SD), or nonscreen-detected disease (NSD). Nonscreen-detected disease patients were then further characterized as nonresponders to the screening invitation (NR), having an interval cancer detected following a negative gFOBt/FIT (INT), having a cancer in a patient who tested positive but did not attend for colonoscopy (NA), or having a cancer in a patient who did not have cancer detected at colonoscopy following a positive screening test (CN). Patients who had an initially suspicious adenoma detected through screening, and as a result of subsequent investigations had colorectal cancer detected within 6 months of the invitation for screening, were termed SD.

Individual patient records were then interrogated on a case-by-case basis to identify further clinicopathological variables for analysis. Tumours were staged according to the conventional tumour node metastasis (TNM) classification (fifth edition) 28. Polyp cancers that were managed endoscopically and did not undergo formal resection were assumed to be node negative and classified as TNM Stage I. Additional high-risk tumour features, such as poor differentiation, the presence of venous invasion, peritoneal involvement and margin involvement, were identified from pathology reports.

Both the absolute neutrophil count and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were used as markers of the preoperative SIR and were obtained from preoperative blood results taken most immediately and not more than 6 weeks before surgery. A previously validated threshold of an NLR ≥ 5 was used as evidence of a significantly elevated SIR 9. An absolute neutrophil level greater than 7.5 × 109 l was defined as elevated based on local laboratory guidelines.

Permission for the study was granted by the Caldicott Guardian of the screening dataset and by the West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer MCN Management Group. Data were stored and analysed in an anonymized manner.

Statistical analysis

Associations between categorical variables were examined using the χ2 test. For ordered variables with multiple categories the χ2 test for a linear trend was used. Fisher's exact test was used for assessing associations where the expected individual cell counts were less than five. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA)

Results

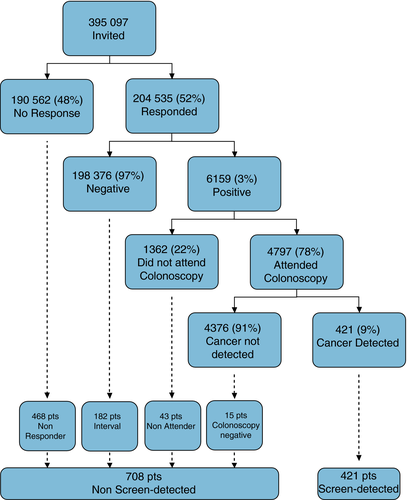

From April 2009 to March 2011, the period of the first complete round of screening in NHS GG&C, 395 097 individuals were invited to participate, 204 535 (52%) responded and 6159 (3.0%) tested positive. Of those who tested positive, 4797 (78%) individuals proceeded to colonoscopy and 421 (9%) patients had cancer detected (SD) (Fig. 1). These figures differ slightly from previously published work by our group due to updating of the data within the Bowel Screening IT System 29. After cross-referencing with MCN and SMR06 datasets, 708 patients with NSD colorectal cancer were identified [468 (65%) patients NR; 182 (25%) patients INT, 43 (6%) patients NA; 15 (2%) patients CN]. This generated an estimated sensitivity and specificity of the first round of the gFOBt/FIT screening test, for the detection of cancer of 72.4% and 97.2% (Table S1).

Comparison of screen-detected and nonscreen-detected colorectal cancer

Screen-detected disease patients were more likely than NSD patients to be male (P = 0.002), have more distal disease (P = 0.003) which was of an earlier stage (P < 0.001) and to undergo a procedure with curative intent (P < 0.001) (Table 1). In those undergoing a curative procedure, SD patients had a less advanced T-stage and less evidence of venous invasion, peritoneal involvement and margin involvement (P < 0.05). They also had less evidence of an elevated preoperative SIR judged by the NLR and the absolute neutrophil count (Table 2). A stage by stage analysis of factors was then carried out (Table S2). Patients with SD tumours had less evidence of an elevated SIR in Stage II and III disease. There was no significant difference in venous invasion rates between SD and NSD tumours in all four stages (Table S2).

| All patients, n (%) | SD, n (%) | NSD, n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1129 | 421 | 708 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 64 | 437 (39) | 164 (39) | 273 (39) | |

| 64–70 | 300 (27) | 114 (27) | 186 (26) | |

| > 70 | 392 (35) | 143 (34) | 249 (35) | 0.762 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 447 (40) | 142 (34) | 305 (43) | |

| Male | 682 (60) | 279 (66) | 403 (57) | 0.002 |

| Site | ||||

| Proximal to splenic flexure | 325 (29) | 100 (24) | 225 (32) | |

| Distal to splenic flexure | 795 (71) | 321 (76) | 474 (67) | 0.003 |

| Synchronous | 9 (1) | 0 | 9 (1) | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I | 318 (28) | 191 (45) | 127 (18) | |

| II | 285 (25) | 93 (22) | 192 (27) | |

| III | 284 (25) | 103 (25) | 181 (26) | |

| IV | 220 (20) | 28 (7) | 192 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Unstaged | 22 (2) | 6 (1) | 16 (2) | |

| Management intent | ||||

| Curative procedure | 872 (77) | 393 (93) | 479 (68) | |

| Palliative procedure | 102 (9) | 8 (2) | 94 (13) | |

| No procedure | 155 (14) | 20 (5) | 135 (19) | < 0.001 |

| All patients, n (%) | SD, n (%) | NSD, n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 872 | 393 | 479 | |

| T-stage | ||||

| 0/1 | 233 (27) | 149 (38) | 84 (18) | |

| 2 | 124 (14) | 63 (16) | 61 (13) | |

| 3 | 365 (42) | 153 (39) | 212 (44) | |

| 4 | 150 (17) | 28 (7) | 122 (26) | < 0.001 |

| N-stagea | ||||

| 0 | 522 (66) | 228 (69) | 294 (64) | |

| 1 | 182 (23) | 73 (22) | 109 (24) | |

| 2 | 89 (11) | 32 (10) | 57 (12) | 0.138 |

| Differentiationb | ||||

| Poor | 69 (8) | 24 (6) | 45 (10) | |

| Moderate/well | 795 (92) | 368 (94) | 427 (90) | 0.066 |

| Venous invasionc | ||||

| Present | 405 (50) | 163 (44) | 242 (55) | |

| Absent | 413 (50) | 213 (57) | 200 (45) | 0.001 |

| Peritoneal involvementa | ||||

| Present | 128 (16) | 20 (6) | 108 (24) | |

| Absent | 665 (84) | 313 (94) | 352 (77) | < 0.001 |

| Tumour perforationa | ||||

| Present | 39 (5) | 4 (1) | 35 (8) | |

| Absent | 754 (95) | 329 (98) | 425 (92) | < 0.001 |

| Margin involvementa | ||||

| Present | 27 (3) | 5 (2) | 22 (5) | |

| Absent | 766 (97) | 328 (98) | 438 (95) | 0.012 |

| Absolute neutrophil countd | ||||

| > 7.5 × 109 | 70 (9) | 13 (4) | 57 (13) | |

| ≤ 7.5 × 109 | 710 (91) | 315 (96) | 395 (87) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratiod | ||||

| ≥ 5 | 123 (16) | 28 (9) | 95 (21) | |

| < 5 | 657 (84) | 300 (91) | 357 (79) | < 0.001 |

- a n = 793 resections.

- b n = 866 resections.

- c n = 818 resections.

- d n = 780 resections.

Comparison of interval and screen-detected cancers

Interval cancer patients were more likely than SD patients to be female (P < 0.001), have more proximal disease (P < 0.001) and more advanced disease (P < 0.001) and less likely to be managed with curative intent (P < 0.001) (Table 3). In addition, they were more likely to have adverse prognostic factors such as venous invasion (P = 0.026) and an elevated preoperative SIR (P = 0.025) (Table 3). On stage by stage analysis, however, these differences failed to retain statistical significance. In particular, venous invasion rates were similar in Stage I (17% INT vs 25% SD, P = 0.344), Stage II (57% INT vs 47% SD, P = 0.272) and Stage III (71% INT vs 70% SD, P = 0.970) disease.

| INT, n (%) | SD, n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 182 | 421 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| < 64 | 64 (35) | 164 (39) | |

| 64–70 | 59 (32) | 114 (27) | |

| > 70 | 59 (32) | 143 (34) | 0.765 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 91 (50) | 142 (34) | |

| Male | 91 (50) | 279 (66) | < 0.001 |

| Site | |||

| Proximal to splenic flexure | 69 (38) | 100 (24) | |

| Distal to splenic flexure | 113 (62) | 321 (76) | < 0.001 |

| Synchronous | 0 | 0 | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 37 (20) | 191 (45) | |

| II | 45 (25) | 93 (22) | |

| III | 53 (29) | 103 (25) | |

| IV | 46 (25) | 28 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Unstaged | 1 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| Management intent | |||

| Curative procedure | 130 (71) | 393 (93) | |

| Palliative procedure | 20 (11) | 8 (2) | |

| No procedure | 32 (18) | 20 (5) | < 0.001 |

| T-stagea | |||

| 0/1/2 | 43 (33) | 212 (54) | |

| 3/4 | 87 (67) | 181 (46) | < 0.001 |

| N-stageb | |||

| 0 | 77 (61) | 228 (69) | |

| 1/2 | 49 (39) | 105 (32) | 0.137 |

| Differentiationc | |||

| Poor | 13 (10) | 24 (6) | |

| Moderate/well | 114 (90) | 368 (94) | 0.118 |

| Venous invasiond | |||

| Present | 68 (55) | 163 (43) | |

| Absent | 56 (45) | 213 (57) | 0.026 |

| Absolute neutrophil counte | |||

| ≥ 7.5 × 109 | 12 (9) | 13 (4) | |

| < 7.5 × 109 | 115 (91) | 315 (96) | 0.021 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratioe | |||

| ≥ 5 | 20 (16) | 28 (9) | |

| < 5 | 107 (84) | 300 (91) | 0.025 |

- a n = 523 (100%) patients managed with a curative intent.

- b n = 459 resections.

- c n = 519 (99%) patients managed with a curative intent.

- d n = 500 (96%) patients managed with a curative intent.

- e n = 455 (87%) patients managed with a curative intent.

Comparison of interval and nonresponder cancers

Interval cancer patients were more likely than NR patients to be female (P = 0.034) (Table 4). There was a trend towards INT patients having less advanced (P = 0.052) and more proximal disease (P = 0.090), but this did not reach significance at the 5% level. When patients who were treated with curative intent were examined there was no difference in adverse pathological features between INT and NR patients. There was a trend for NR patients to have an elevated preoperative SIR (P = 0.059) compared with INT patients (Table 4).

| INT, n (%) | NR, n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 182 | 468 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| < 64 | 64 (35) | 188 (40) | |

| 64–70 | 59 (32) | 113 (24) | |

| > 70 | 59 (32) | 167 (36) | 0.816 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 91 (50) | 191 (41) | |

| Male | 91 (50) | 277 (59) | 0.034 |

| Site | |||

| Proximal to splenic flexure | 69 (38) | 142 (30) | |

| Distal to splenic flexure | 113 (62) | 317 (68) | 0.090 |

| Synchronous | 0 | 9 (2) | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 37 (20) | 74 (16) | |

| II | 45 (25) | 130 (28) | |

| III | 53 (29) | 115 (25) | |

| IV | 46 (25) | 135 (29) | 0.052 |

| Unstaged | 1 (1) | 14 (3) | |

| Management intent | |||

| Curative procedure | 130 (71) | 306 (65) | |

| Palliative procedure | 20 (11) | 67 (14) | |

| No procedure | 32 (18) | 95 (20) | 0.210 |

| T-stagea | |||

| 0/1/2 | 43 (33) | 83 (27) | |

| 3/4 | 87 (67) | 223 (73) | 0.210 |

| N-stageb | |||

| 0 | 77 (61) | 187 (64) | |

| 1/2 | 49 (39) | 105 (36) | 0.569 |

| Differentiationc | |||

| Poor | 13 (10) | 29 (10) | |

| Moderate/well | 114 (90) | 273 (90) | 0.840 |

| Venous invasiond | |||

| Present | 68 (55) | 157 (56) | |

| Absent | 56 (45) | 121 (44) | 0.761 |

| Absolute neutrophil counte | |||

| ≥ 7.5 × 109 | 12 (9) | 41 (15) | |

| < 7.5 × 109 | 115 (91) | 242 (85) | 0.160 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratioe | |||

| ≥ 5 | 20 (16) | 68 (24) | |

| < 5 | 107 (84) | 215 (76) | 0.059 |

- a n = 436 (100%) patients managed with a curative intent.

- b n = 418 resections.

- c n = 429 (98%) patients managed with a curative intent.

- d n = 402 (92%) patients managed with a curative intent.

- e n = 410 (94%) patients managed with a curative intent.

Discussion

The results of the present study provide a comprehensive analysis of the outcome from the first round of a stool-based colorectal cancer screening programme. It confirms previous studies that have found that screen-detected tumours are of an earlier stage than nonscreen-detected tumours and reports for the first time that individuals with screen-detected disease have more favourable host prognostic factors than those with nonscreen-detected disease.

Analysis of host factors, such as the presence of an elevated SIR, has not previously been done within the context of a colorectal cancer screening programme. In addition to inflammatory responses in the tumour microenvironment 30, SIRs are now recognized as a key hallmark of cancer 6. In particular there is a wealth of evidence that host factors are associated with an adverse outcome in colorectal cancer, including meta-analyses 7, 11. To date, however, their inclusion as a means of predicting outcome outside in the routine clinical setting has been patchy. In the present study the most readily available measure of the SIR, in the form of neutrophils and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, has been included 31, 32. This additional information adds to the level of detail available for the cohort and is a unique feature of this comprehensive analysis.

It could be argued that the present study, showing that some adverse tumour prognostic factors are less prevalent in SD tumours than in NSD tumours is evidence for the effect of length-time bias, where the identification of indolent slow-growing tumours artificially improves cancer-specific survival by detecting those which have a longer pre-clinical phase 33. When, however, adjustment is made for stage, the two key features in keeping with phenotypically more aggressive tumours, venous invasion and poor differentiation, do not achieve statistical significance. Furthermore, it has previously been postulated that INT tumours are not only those tumours missed by the screening test itself but may also be more aggressive ones that develop within the screening interval 20. Detailed examination of tumour and host prognostic factors in INT compared with NR tumours provides evidence to refute this hypothesis. There was no evidence of adverse tumour features in the INT group when compared with the NR group in the present study. Indeed, there was a trend for NR patients to have evidence of a higher host SIR. Therefore, the conclusion that can be drawn from the present study is that the inherent biological characteristics of SD tumours do not differ from those of NSD disease.

There were higher numbers of cancers in both the NA and CN groups than initially expected. On further investigation, however, it became apparent that a substantial proportion of the NA patients (40%, data not presented), were already under investigation for colorectal symptoms and had sent back the screening test in the midst of undergoing nonscreening investigations. Also, of the 15 patients who were CN, 12 (80%) (data not presented) had polyps detected at colonoscopy and hence were undergoing follow-up. For the purposes of the present study, a cancer diagnosis outwith 6 months of initial colonoscopy was defined as NSD, but it may be argued that these patients would not have been detected at that time had they not participated in screening. Nevertheless, the 15 patients who were CN represent a postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer rate of 3%; this compares favourably with other studies that have examined this outwith screening programmes which have provided rates of 2–8%, albeit with longer (3–5 years) follow-up 34-36. The majority of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancers are thought to arise through procedural factors such as missed lesions and inadequate examination 35. The SBoSP has tight quality control on all colonoscopists requiring to be accredited by the Joint Advisory Group (JAG) and have a greater than 90% caecal intubation rate 37. It was not in the scope of the present study to examine colonoscopy quality indices in more detail, but the low rate of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer was reassuring.

Strengths and weaknesses

The main strengths of the present study include the comprehensive and detailed dataset. Case notes were examined on a case-by-case basis allowing for more detailed analysis of clinicopathological factors at a depth that has not previously been undertaken. For example, in the present study, after case note review, only 2% of tumours remained unstaged compared with 25% in a previous study using population databases 23. In addition, we have included data from nonresponders, which have been absent from other studies, and by utilizing regional and national cancer registry datasets we have comprehensively captured those with NSD disease from corroborative sources.

The main limitation of the study is the fact that this is a prevalence round of a screening programme, and as such these results may not be applicable in subsequent rounds. This is important when analysing data with regard to sensitivity and specificity. A further possible limitation was that all NSD tumours were taken as the main comparison group. Comparing INT with SD tumours might have been a better measure of the impact of screen detection. Nevertheless the present study represents a population setting whereby compliance with the screening programme was just over 50%. Therefore to exclude NR tumours would be to exclude from the study a large proportion of the population invited for screening. A subanalysis comparing SD with INT tumours was undertaken, and no difference in prognostic factors was elicited when adjusted for stage. Such subanalyses will by definition be limited by reduced numbers and hence power, and additional work is required to examine these findings further. Finally, our measure of the SIR was by NLR and not the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS), which has been shown to be a more sensitive measure of host inflammation with regard to outcome 8, but this is a retrospective study and C-reactive protein (required for calculating mGPS) was not routinely measured preoperatively in all hospitals during this timeframe.

In conclusion, the present study reports that patients with SD tumours, independent of stage, had more favourable host prognostic factors than patients with NSD tumours. There was, however, no difference in adverse tumour features associated with an aggressive tumour phenotype. In addition, INT cancers did not appear to have more aggressive features than tumours that developed in the rest of the population, and hence were more likely to arise as a result of the limitations of the testing algorithm itself rather than represent biologically more aggressive tumours. Further work to identify a more sensitive test is required to increase the number of tumours that are detected through screening and hence to improve the outcome in colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the members of the West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network. In addition we would like to thank Annette Little, Paul Burton and Billy Sloan for their help with data extraction and processing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions

D.M.: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis. D.C.M.: study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis. E.M.: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; statistical analysis. E.M.C.: study concept and design; acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; technical, or material support. D.S.M.: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis. P.G.H.: study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision.