The space before, the space beyond: Activism, relationships and social change in the neo-liberal academy

Abstract

The last 20 years have seen exponential growth in participatory research methods in child and youth studies, social work, education and allied disciplines. Scholars internationally have highlighted the ways these methods can connect with other areas of scholarship including children's rights, citizenship and activism. The Binks Hub is a new initiative committed to supporting, promoting and delivering transformative, co-creative research. The funding, monitoring and impact regimes within higher education can mean that delivering these commitments is challenging. This article uses three empirical cases involving participatory methods to reflect on these challenges and examine the connections and disconnections between participatory research and activism. The work of Sassen (2014) is employed to make spaces before and beyond method more visible. These spaces, we conclude, are critical to creating the foundations for relational participatory practice, and ensuring initiatives like the Binks Hub have long-term meaning and value.

INTRODUCTION

The ‘new’ sociology of childhood has involved an ontological shift towards young people as competent social actors, with the right to be involved in decision-making affecting their lives. Children and young people are seen as being in possession of knowledge, skills and capabilities, as active agents. In a research context, this requires critical reflection on adultism and associated power and position. A range of methods (see Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020 for a full review of the wide range of participatory methods) considered ‘participatory’ has become de rigueur in this paradigm, with interest derived from their common commitment to deconstructing power relations, challenging conventional processes of knowledge production and maintaining a position of researching with, rather than researching on (Coyne & Carter, 2018; O'Kane, 2000).

This participative orientation comes with a long and intimate relationship to activism. The common, and often taken-for-granted, methodological position is that participatory methods, in a general sense, have the capacity to democratise knowledge construction. Under the umbrella of participatory methods, there is a broad desire to work relationally with children and young people, starting ‘where they are at’ to identify questions and address issues significant to them. Literature demonstrates that, when used effectively, participatory methods can create possibilities for engaged, ethical, active social science and equitable and creative use of method (recent examples of the diversity of work in this field include James & Shaw, 2022; Williams, 2021; Burke et al., 2019).

The relevance of participatory research is growing in UK academia, with research funders increasingly advocating for its use to strengthen research impact (see, e.g. UKRI, 2022). This is supported by the broader development of ‘engaged scholarship’ and its epistemological concern with community-engaged teaching and research. While not all engaged scholarship is necessarily ‘activist’ (Flood et al., 2013, see also Torres, 2019), academia (and academic researchers) can be a productive site for activism in multiple ways: by producing knowledge to inform progressive social change; by conducting research that involves social change; by creating spaces for progressive teaching and learning and finally, as a site which institutionally can resist and challenge social inequalities and injustices.

Creating sites or spaces for ‘activism’ (we will return to how we define activism shortly) is at the heart of the Binks Hub. Launched in 2022 and interdisciplinary in form, the aim of the Binks Hub is to support, promote and deliver transformative, co-creative research. Funded by the Binks Trust, the Hub seeks to bring together communities, artists and academics to support and conduct research that promotes social justice and makes a difference in people's lives. Methodological inquiry in this context means viewing individuals and groups as equals when it comes to sharing and developing knowledge. It means that rather than conducting research on participants, our future research will prioritise collaboration with citizens and community members. Across all our work, a range of participatory and creative approaches will be utilised to support citizens and groups involvement in research on issues that affect them. It also means that the public, government and policy actors will be engaged in this conversation so as to raise the profile of citizen and community-led research.

One of the key methodological observations we made when establishing the Binks Hub was that interest in participatory research methods was gaining pace in the UK. Policymakers were becoming interested in what was increasingly referred to as ‘lived experience’ (see, e.g. The Scottish Government, 2022; Abbott & Wilson, 2014; McIntosh & Wright, 2019). At the same time, ‘co-produced’ and ‘creative’ research methods were more prevalent among research funding in the UK. The Arts and Humanities Research Council's Connected Communities programme is a key example, funding over 300 projects each committed to co-production, participation and community university (Facer & Pahl, 2017). In an academic setting, there was also much to celebrate. An internal mapping exercise conducted to support the Hub's establishment demonstrated a wealth of interdisciplinary community led-research across the University using a range of participatory methods. The Childhood and Youth Studies Research Group, based in the Moray House School of Education and Sport at the University of Edinburgh has, for example, been leaders in this field in the context of childhood and youth studies for decades; this special issue is just one example of their work.

In spite of this momentum, we have observed that the UK model for higher education (often referred to as a neo-liberal regime, see Maisuria & Cole, 2017) can act as a constraining force. Research funding is too often short-term and offers insufficient time for relationships to organically develop (and be sustained) with citizens and community groups. The focus on institutional growth for commercial and monetary gain has had the consequence of burgeoning administrative workloads which limit the time academic researchers can meaningfully spend in communities. Participatory research, despite being praised, can in practical terms sit in conflict within university structures driven by annual reporting, quantitatively driven key performance indicators (KPIs) and scholarly outputs. Dedicating time to relationships with institutional requirements and funding cultivates activism and impact. Such spaces have particular characteristics: slowness, patience, starts, stops, interruptions and interferences. They follow what Sassen (2014) describes as spaces before method, which necessitates spending time reflecting on prevailing concepts and frameworks before undertaking empirical work. In our application of this concept, we see such spaces as critical to those working with participatory approaches, especially for those working with children and young people and/or for groups who are marginalised in some way.

Such practices, especially if unfunded, can sit in opposite to the principles and practices increasingly prevalent in UK Universities that value marketisation, turnover and accountability. This raises two issues for the Binks Hub. The first is how, as a fledging initiative, we navigate and challenge neo-liberal principles and practices. The second, and connected question, is how we position our work relative to ‘activism’. What does activist research mean in the current higher education context, and to what extent will we be able to regard our work as a form of scholarly activism, or ourselves as activist- scholars?

To consider our own path forwards, we have selected three past empirical case studies that employed participatory research methods. Two were doctoral studies, and one was a small-scale enquiry focused on social work practice. We selected these completed projects as a means of reflecting on how, as researchers within Russell Group University, we have navigated the challenges discussed above. Brought together they provide material for a reflective dialogue about participatory methods and their complex relationship to activism, and in turn, how we can advance our own theoretical and methodological practice. We are inspired by the work of Maunther and Doucet (2003) who note that while the importance of being reflexive is often discussed, less attention is given to actually doing reflexivity. We have used this approach elsewhere and found it to be a productive means of engaging in our methodological practice and its relationship to theory (Davidson and McMellon, 2021, see also Davidson et al., 2021 and Wright et al., 2021).

We begin with a short contextual section which provides a broad overview of participatory research, and second, activism. Here we do not provide a full overview of the diverse range of participatory research methods, nor do we give a decisive definition of ‘activism’ or ‘activist research’ (see Taft and O'Kane (2023) in this collection for a fuller analysis). Rather, our intent is to provoke reflection in the context of our own work. With this framework established, we move on to present three empirical case studies which draw on past research completed by the authors. We do not introduce the entire research project for any of the case studies and thus you will not see a full research cycle from design to knowledge exchange. Instead, we focus on particular unique phases, moments, experiences and challenges that emerged as part of our engagement in participatory research. The final sections draw the analysis together to reflect critically on our past engagement in participatory research and its relationship to ‘activism’. Through this active process of reflexivity, our hope is that it informs the development of the new Binks Hub and our engagement in activist research more widely.

YOUNG PEOPLE AND PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH

In their review of participatory research, Cornwall and Jewkes (1995) ask a fundamental question, ‘if all research involves participation, what makes research participatory?’ (p 1668). As with all answers to social research dilemmas, the answer is ‘it depends'. We are in agreement with Bourke (2009) who notes there are ‘no strict rules for what constitutes participatory research or even clarity about the essential ingredient’ (p. 458). Rather how you decide what makes research participatory depends on who you ask, where and when they are and the motivations and aims of the social enquiry being conducted.

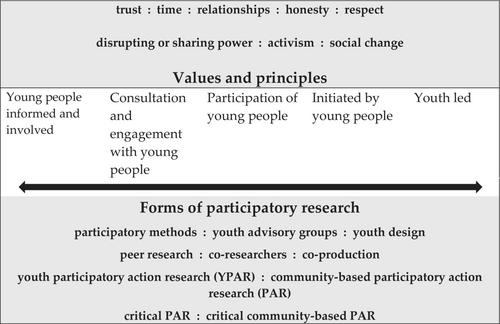

This is an important starting point since it recognises that participatory research is a broad umbrella under which a number of collaborative, inclusive or action-based research methods and approaches are located. It can span a continuum of project types and can be undertaken in many ways. Participatory research involving young people has, for example, focused on listening to children and young people's experiences (Clark, 2012), involving them in consultations (Minds, 2021; Ofsted and Care Quality Commission, 2022), acting as lead researchers or co-researchers (e.g. Cuevas-Parra & Tisdall, 2019; Hunleth, 2011; Lee et al., 2020) and engaging them in participatory advisory groups (Collins et al., 2020).

Figure 1 shows the continuum of participatory research involving young people. Note we have deliberately included a double-ended arrow to illustrate that levels of involvement can vary within individual projects, with research becoming more or less participatory at different stages of the research (Brown, 2022). It also helps to remind us that each form of research is valid; it does not get ‘better’ as it becomes more participatory.

Figure 1 also shows that significant components of participatory research are ethical, methodological and political values and principles. Participatory research is respected for its capacity to prioritise ‘lived experiences’ and disrupt power imbalances. It is regarded as interactive rather than extractive, and thus inclusive and ethical, and can happen in a range of different spaces—from schools, public institutions, community organisations and social movements. For Foster (2016), the collaborative process provides ‘new’ ways of seeing and the ability to defamiliarise the ordinary and expose the ways that the everyday are shaped by powerful social structures. A central objective is knowledge democracy, wherein the knowledge and epistemologies of marginalised groups and communities are not simply given respect, but considered essential to supporting civic engagement (Ginwright et al., 2006) delivering social change (Janes, 2018) or empowering communities (Hacker, 2013).

The language of social change is strongest, not surprisingly, within forms of ‘action research’ (Figure 1). Examples of such forms of research include youth participatory action research (YPAR) and community-based participatory research (see, e.g. Anyon et al., 2018; Hacker, 2013). These are forms of participatory research that involve researchers and young people working collaboratively with the explicit objective of taking action, including social change. Kemmis and McTaggart (2005, p.597) suggest that participatory action research ‘aims to help people recover, and release themselves, from the constraints of irrational, unproductive, unjust, and unsatisfying social structures that limit their self-development and self-determination’. Explicit connections to activism are made within ‘critical’ forms of action research (CPAR), with research in this field being focused on ‘documenting, challenging, and transforming conditions of social injustice’ (Fine & Torre, 2021, p. 3). Critical approaches are a move towards a ‘decolonising’ research method with the potential for healing and social justice (Chilisa, 2012, p. 251).

The broad participatory research praxis and its rhetoric of empowerment have been subject to discussion. O'Neill's work, which explored the transformative potential of participatory arts, noted this approach is ‘difficult to put into action, is time consuming, and involves lots of time, energy, commitment and emotional labour’ (2012, p. 170). There are further debates relating to the relationship participatory approaches have to power and action. This can be ambiguous since not all participatory projects will necessarily have an explicit focus on shifting or challenging power or find ‘power’ difficult to resolve through method alone. Similarly, participatory methods in themselves do not tackle social injustice or necessarily empower it (Davidson, 2017). The imagining of collaborative research as producing ‘better’ or more ‘ethical’ types of knowledge about young people is problematic since they can also fail to reflect on the views of those unable, unwilling or excluded from participation.

ACTION, ACTIVISM AND ACTIVIST RESEARCH

We have discussed the complex relationship that participatory research methods, especially those considered ‘action’ research, have with social change. Despite ‘action’ being a key element of participatory research, it is one of the most challenging aspects of our work to define, achieve and measure (Bertrand et al., 2020; Guy et al., 2020). In the broadest sense ‘action’ is the process of doing something, typically to achieve some sort of aim. Most often in the context of participatory research this ‘aim’ involves positive change or improvement, although ‘action’ is often ill-defined, or used—not always helpfully—interchangeably with ‘social change’ (Reid et al., 2006, pp. 316–317). Moreover, there are also too often assumptions about how action should be defined and achieved. Often this is action at a macro or collective level. This, Reid et al. (2006) argue, is problematic since expectations within a collaborative project can vary significantly and result in small, micro-level forms of action going unnoticed or undervalued. Social change at this scale can come in the form of unexpected new relationships, attitudinal change, and new expectations.

There are also expectations about what constitutes ‘action’ within higher education. Better understood as research ‘impact’, in the UK context this is defined as work that has ‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia’ (Research Excellence Framework, 2021, p. 68). While such aspirations are not in themselves problematic, they arguably establish expectations within the research community about the nature and magnitude of impact that has the greatest value. This is significant given the focus that funding bodies and research councils give to demonstrating impact.

Complexities exist in how activism is defined and understood. As with participatory research, activism is motivated by a desire to make a difference and address common problems. Ballard and Ozer (2016, p. 1) define youth activism as ‘the organized efforts of groups of young people to address the root causes of problems in their local, national, and global communities’, noting that it can come in many forms ‘including, in person or virtual, grassroots or joining an established organisation or cause, one-time participation or long-term commitment’. From a popular perspective, such a description is typically associated with visible, loud and direct action, outwardly looking activities, such as protests and demonstrations, strikes, sit-ins, consumer boycotts or non-violent civil disobedience. However, activism need not be synonymous with direct action, and from the perspective of young people themselves, such understandings can be limiting. Taft (2011, p. 33) discusses the multiplicity of forms that activism can take and pushes for a widening of definitional boundaries to ensure that a diversity of ideas and forms are considered as part of the ‘change’ or outcomes being sought. Simon and Norton (2011) likewise state that ‘activism’ can rarely fit into a single definition, arguing instead for a continuum which accounts for its different forms and outcomes. For academics, this complexity extends into their own identity. Where on the continuum should one's work be situated? Should one seek to conduct scholar-activism as and when required (something you do), or present a permanent commitment to being a scholar-activist (something you are) (Joseph-Salisbury & Connelly, 2021:51)? Tempered radicalism offers an alternative relationship to power, representing approaches which seek to change the system (in our case higher education) while remaining part of it (Meyerson & Scully, 1995).

Interestingly, the activism continuum can also include what Pottinger (2017) carefully describes as ‘modest, quotidian acts of kindness, connection and creativity’ (p. 217). Such ‘quiet activism’ encompasses small, everyday and mundane actions. This may take place at an individual scale, yet retain huge potential for delivering ‘change’. This echoes Stenning's (2020) work on austerity, which emphasises the importance of paying attention to the small stuff—the little effects, the little acts and the little affects—as a means of understanding ‘big’ structural processes. Little acts by households, she concluded, made a difference emotionally and helped provide a sense of (although limited) control and autonomy. Winter et al. (2020) drew similar conclusions, reporting forms of ‘quiet activism’ in a school setting. Examples included staff giving children extra food at lunch time, providing hygiene packs to families (with staff often paying for this themselves) and simply ‘caring’. Corey (2021), similarly, emphasises the ways in which silence can speak and have power in activism. Acts of care, emotional support and silence resistance may be small in scale, but no less political or potent in their intent.

In a similar way, we can think about the intimacies formed in, and around, activism, and shine a light on the back stage activities that for Reid et al. (2006) go unnoticed. O'Shaughnessy and Kennedy (2010) use the term ‘relational activism’ to describe a host of activities, ranging from working with community members to teach tomato canning, through to fixing bikes, and volunteering at community events. These might not be conventionally ‘activist’, but rather be in service to more public acts of activism. Such a service helps build bridges in the private sphere which in turn foster trust, emotional ties and comradery in communities and between activists, and support change in daily practices and lifestyle. In a collection by Zaunseder et al. (2022), a range of grassroots activities are described as spaces where collectivity, solidarity, community, resistance and reclamation can occur. This work is a useful reminder that large-scale change is the product of the ripples of small-scale, collective action (O'Shaughnessy & Kennedy, 2010, p. 555).

Ideas of quiet, micro, small, relational or backstage activism take us back to thinking about the ‘value’ assigned to particular kinds of action within research. Reid et al. (2006) discuss the challenges of finding action in participatory research, arguing that too often there is an ‘idealised’ expectation that research delivers large-scale change to structures and macro social processes (p. 317). This, they continue, means that there is less space for forms of action that are smaller, or ‘quieter’. These might be impacts that affect an individual or a group or might be an impact that is only significant at a local level. Such expectations are apparent in the UK Research Excellence Framework (2021) where the ‘best’ impact tends to prioritise examples of macro change, such as being able to demonstrate that your research has influenced policymaking or legislative change. While we (as a group of academic researchers) are concerned with, and interested in enabling the small, quiet forms of activism, these can conflict with the dominant institutional ideology of what type of ‘action’ counts.

For academic researchers, this is tricky terrain to navigate since these smaller or quieter forms of activism are often unplanned and happen before a proposal is written and funded, or happen after the research is formally concluded. So, for example, this might be initial time spent in potential research settings, making connections and networks to on-the-ground experts. As the research focus becomes firmer, it might involve ‘being there’, ‘hanging out’, having conversations and sharing experiences. If the research is funded and able to formally proceed, finances can limit the extent to which researchers are able to have conversations and interactions that have no clear outcome or ‘impact’ measure attached to them. At the end, once formal research funding ends, opportunities to continue collaborative knowledge exchange activities can be limited. Even with best intentions, academics can find themselves unable to sustain relationships with partners. We are not suggesting that individuals and groups involved in research need researchers to remain, indefinitely, in a research setting. Our concern is that funding regimes and associated expectations about impact can leave little space for established relationships to be maintained. The question begs, where does this leave those involved? Some, full of excitement, capacity and resources move forward without any need/desire for an academic partner, others perhaps are left hanging without adequate support to continue their activism, in whatever form it takes.

A CRITICAL REFLECTIVE DIALOGUE—INTRODUCING THE CASES

Having set out this maze of ideas about participatory research and activism, we move on to a reflective review of completed participatory research projects. Each of the three case studies described uses participatory methods with young people. While none were explicitly focused on activism, nor involved young people who considered themselves ‘activists’, this reflective exercise has encouraged us to pay closer attention to the role, place and value of ‘activism’, and its relationship to participatory methods, and method more generally. In particular, it has enabled us to think more clearly about how to effectively use participatory research methods while balancing our desire to be responsible methodologists alongside the constraints of the higher education system.

Case 1: Participation in researching antisocial behaviour

For my (Davidson) doctoral research, I conducted a 12 month ethnographic study in a deprived suburban housing estate in Scotland (See Davidson, 2017 for greater detail). The aim was to explore the diverse ways young people define, experience and relate to ‘antisocial behaviouri’ (ASB). The research was, from the outset, defined broadly as ‘participatory’ and used a range of different methods to work collaboratively with young people on the topic of ASB. My interest was not explicitly in activist-scholarship, or in being an activist. However, I was concerned about the increased stigmatisation of young working-class people as a result of ASB policy. I wanted to undertake participatory research that shifted from an adult focus, to centre young people's voices and perspectives. For the study, I spent significant time volunteering in a local youth club. I also ran activities in the local library, local youth clubs and public spaces. As relationships with young people developed, I gradually introduced a ‘toolkit’ of creative methods. These included activities developed with, and for, young people. For example, community mapping involves working with groups of young people to identify spaces and places important to them. Working collaboratively with a local artist and the researcher, a small group of young people wrote postcards with messages for adults in the community and created a series of posters.

Some of the young people involved in the research were members of predominantly groups involved locally in ASB, and whose behaviour was the foci of police. Several were recipients of punitive sanctions such as acceptable behaviour contacts, electronic monitoring devices and criminal charges. These young people made frequent complaints about the regulatory practices of the police and said they often found themselves scrutinised even when they were ‘just walking down the street’ or questioned about crimes they had not been involved in. Such targeting, the groups felt, was discriminatory and fuelled an existing mistrust, and in some cases hatred, towards the police. They frequently described incidents of being moved on and searched, while others recounted more serious (although unfounded) claims of police brutality. The young people emphasised their agency when talking about their involvement in antisocial behaviour. They rationalised their behaviour as their own choice, a product of their own decision making, and therefore a form of ‘action’.

What was notable, from a research perspective, is that those young people most stigmatised by authorities frequently found ‘participation’ in research activities challenging. There were a number of reasons for this. Perhaps, the most important was that the young people found the experience of being asked to share their views and experiences unusual. While this applied to my research, they also discussed examples from everyday life. There was frustration over a piece of derelict land which young people saw as ‘theirs’ being redeveloped without any consultation with them. Others expressed dismay at the many ‘dead spaces’ in the area and the commercialisation of local football pitches. Stories were told of social workers, police or teachers ignoring their views. If one's views are consistently overlooked and neglected, it is not surprising that collaboration with a researcher from ‘the university’ is unusual, not to say difficult. Working in a truly collaborative way requires time.

As a consequence, some young people opted out of planned group sessions, did not turn up or found it difficult to articulate their views since, in one boy's words, ‘no-one had ever asked him this before’ (see also Rasool, 2018, p. 116). Responding to this as a researcher required a huge amount of flexibility, something likely not possible had this not been a doctoral study where there was more time built into the process for learning and development. It also raised the thorny question of participation and whether, given my extended and somewhat persistent presence in their space as a volunteer, they had meaningfully chosen to take part.

My endeavour to ensure marginalised young people's voices were included was also problematic for other young people. While the group saw their own behaviour as disrupting social norms and claiming re-public spaces they felt excluded from, their presence in public spaces and the youth club was causing some peers distress and anxiety. I was challenged more than once by other youths over my decision to include the group in the research process. Riach (2009) talks about ‘sticky moments’ where the “protocol and research context [are] actively questioned or broken down’(p.357). In this case, the youth perspective was not only heterogeneous, but divided, and participatory research was both challenged and challenging.

The young people ultimately exhibited their work in the youth club, and latterly, in the local community centre for an extended period. Local politicians and ASB professionals attended these events, young people were interviewed for the local newspaper and the researcher presented the young people's work at several local events, including a local policing conference. While individually young people and youth workers reported benefiting from involvement in the project, there was limited impact on ASB policy. The infrastructure necessary for this small project to lead to bolder forms of action was simply not yet in place. The demands of the higher education system, especially in the context of precarity for early career researchers, meant that continued meaningful community relations with the youth centre were not possible after the research concluded. However, informal relations were maintained by the researcher, and this has resulted in new collaborative projects being planned.

Case 2: Participation in research as relational activism?

When I (Roesch-Marsh) began working on the application for an eNurture funding study in 2019, I was pleased to see that there was a requirement for pre-application consultation with young people; something which, although rarely funded or supported within the neo-liberal academy, I always try to work into my research planning. I approached a local charity that works with those leaving care to see if their youth advisory group would be willing for me to come to one of their meetings. Like most young people exiting the care system, the young people supported by this charity were experiencing an accelerated and compressed transition to independence (Stein, 2005).

The youth advisory group that worked with the charity were a group of 10 young people who had experience with the care system and through care and aftercare services. They met monthly to discuss organisational plans and service developments and fed into the inspection and fun-raising cycle for the charity. When I asked about why they had volunteered to be on the advisory group, they spoke about the group being a chance to meet each other but, more importantly, they saw it as an essential means of influencing the work and direction of the organisation for the benefit of other young people.

Their interest in taking part in and supporting my proposed research was underpinned by similar motives. They spoke about the digital exclusion of care-experienced young people and how so many live in poverty and suffer from social isolation. They spoke about a lack of power in the care system, having their phones removed from them and checked by staff and having their Wifi switched off as a punishment. They felt a research study on this topic was definitely worth doing, they could see that the online world was impacting their mental health and the mental health of their friends in a number of good and bad ways (Roesch-Marsh & Cooper, 2021).

The group were supported by a staff member named Shona whose job it was to develop and sustain their work. She organised meetings and social activities to help the group bond. She helped them to think through their priorities and engage with organisational requests. She protected them from too many demands; there were often people inside and outside the organisation, like me, wanting to ‘consult’ with them about one thing or another. A lot of her work was also about sorting out the logistics of participation by organising travel and childcare.

She and the group members knew each other really well and there was a lot of joking and sharing between them whenever we met. As a result, the group felt like a safe, fun, comfortable place to be and share. When this project was finally funded and the research began, it was the foundations established by the youth advisory group and Shona that helped to get it off the ground. The young people that we were able to involve in interviews, focus groups and arts-engaged workshops had all experienced incredible adversity. Many had experienced abuse and neglect in their families. Many had been passed from pillar to post in a dysfunctional care system. Their lives were busy and complex when we asked them to engage with our research but they were interested because we approached them through Shona and the youth advisory group, who also offered follow-up support after their engagement with us.

Although the final stages of the project were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, findings from the research were used to devise and pilot training for foster carers and residential workers in the digital world and to make an animated film, which was created with care-experienced artists. The project also led to further two projects around digital rights and care-experienced people, one of which is taking forward this work on a larger scale and is being led by care-experienced people themselves (Who Cares? Scotland, 2022).

The success of the project demonstrates the power of relational activism at its various levels. The bridging work between people creates the foundations for everything that follows it. But the way this work is done also creates a collective ethos and way of being together that is transformative. An equal place at the table and involvement in decision-making is hard to achieve in adult-led organisations but this charity was trying to put the views and feelings of the young people at the centre of their efforts to provide a good service and a different, more positive, experience for the young people they were working with. The work of this small local youth advisory group was able to influence developments on a national level with follow-on work by a larger national charity who picked up the themes the advisory group and other young people shared with me during the course of the project. In this way we can see how relational activism in the community can provide a foundation for relational research, which in turn can support further relational activism and, hopefully, result in changes in practice and wider society.

Case 3: Participation, activism and play

In my (Wright) doctoral research, I worked in partnership with 10 young people aged 15–20 as ‘Emerging Researchers’ (see Wright, 2021 for greater detail). Based on the traditional territory of the unceded land of the W̱ SÁNEĆ, Lkwungen, Wyomilth peoples of the Coast Salish Nation, Greater Victoria, the research explored the role of play-based researchii in young researchers' lives. As part of the research, the Emerging Researchersiii were trained in play-based research, before designing and conducting research with other young people in their community. The central aim of the doctoral research was to explore ‘play’ within research, its role in relationships, and its potential to foster spaces for reflexive dialogue on social issues in young people's lives. Grace (2019) argues that play is not merely for frivolity of childhood. Rather, it is a way for humans to find flow, alleviate stress, explore critical concepts and understand and reflect on the world around them (Grace, 2019). Similarly, art forms can ‘generate dialogue by creating temporary or permanent social spaces’ to change the ways we see ourselves and social situations to raise social consciousness (Bell & Desai, 2011, p. 289). This play-based research approach, which values fluidity and messiness, agitates neo-liberal views of research excellence, especially relative to ‘outcomes’ and ‘impact’.

Within the research, a range of structured (e.g. River Journey; Visual Explorer Cards; Jenga) and unstructured play-based methods were used, alongside unprescribed ‘chill’ spaces (see Wright, 2021 for tool details). This approach allowed for ongoing co-creative processes that respected fluidity over fixedness (Bright & Pugh, 2019). Play took place in the margins and between spaces of the structured activities in the form of messy conversations and playful moments. For example, a conversation on systemic discrimination of persons with disabilities in formal education emerged during an early morning camping breakfast discussion. Dialogue on respect for political choice in relation to human rights arose next to a fire after a day of play-based research and everyday interaction. Neither of these conversations occurred during the formal play-based research activities (e.g. mapping, jenga), yet emerged in the margins of the—structured space when young people were at play (e.g. playing self-developed games around the fire) or after a day at play.

As the Emerging Researchers connected with one another through acts of collective play, their comfort and confidence to speak about critical social issues that were important to them increased and occurred more frequently. This was apparent at a research training week at a campsite. Here, the researchers learned play-based research methods and engaged in a variety of activities (e.g. paddleboarding, hikes, swimming, cooking). Among the play, significant conversations on politics, values, and discrimination arose. For example, while sitting around the fire and playing young person-led campfire games, a few Emerging Researchers raised the challenge of being unable to vote under 18 years of age and highlighted that adults with less knowledge of different political platforms have the power to vote. This political dialogue also fostered value and rights-based conversations around respect and discrimination. For example, a conversation arose around left-leaning political perspectives in contrast to United States' President Donald Trump. This conversation opened space for the Emerging Researchers to reflect on their own values in relation to their lived experiences and experiences of persons discriminated against and oppressed in society.

As the majority of Emerging Researchers had a strong relationship with nature, the interconnection between nature play and climate activism was also evident. One evening while hanging out, the conversation turned to the importance of climate strikes, encouraging peers at school to participate, and the lack of recognition given to indigenous young people in the global conversation. This arose during a time-limited discussion on planning for next steps in leading research. Too often researchers will focus on their own agenda without recognising the value of these ‘between’ spaces. These liminal spaces can have an important role in enacting young people's political potential in their everyday spaces (Hadfield-Hill & Christensen, 2021).

In my research, I took time to pause for these unintended conversations to emerge and flow without blocking them, rushing onto my own research agenda, or asserting power as the adult researcher. As in Davidson's research, this research was not about activist youth. Nor did the young people see themselves as activists. Yet both the dialogue and the activities and emotions expressed by the young people danced on the margins of it.

Elwood and Mitchell (2012) suggest that young people's dialogue on the everyday can constitute an important space for their own politics as well as their formation as political actors themselves. In my research, some of the conversations acted as a ripple effect for shared action across the group and beyond. However, having a space for shared dialogue had value in itself. Crucially, it was the liminal and in-between spaces that were openings for dialogue without a targeted outcome. The outcome was neither ‘impact’ in a neo-liberal sense, nor conventional activism. However, they fostered critical reflexivity and space for further germination of ideas and future action.

DISCUSSION: FINDING A WAY THROUGH THE MAZE

The research case studies shared in this article are not explicitly on or about activism, nor are they activist endeavours. However, we approached our research with an understanding of the injustices present, and a desire for young people to make sense of their own experiences and contribute to change at different levels. In Davidson's case, this was the categorisation of places and people as ‘antisocial’ and the absence of young people's views and opinions herein. For Roesch-Marsh, injustice was towards the continued and long-standing understandings of care-experienced young people as marginalised and vulnerable, and for Wright, the research was in response to ‘adulist’ critiques about the nature and form of participatory research, and the notion that ‘play’ be categorised as childlike, and therefore not valuable in young people's lives or as part of a robust research process. Each project engaged young people in relational practice with intended and unintended dialogues around critical social justice issues. Interactions and activities considered precursors to, or in service to, activism emerged in organic forms where time and space, without traditional restrictions, allowed. Sassen's (2014) ‘space before method’ is a particularly helpful way of conceptualising the common reflections in these three pieces of work. The ‘space before method’ starts from a position of epistemic indignation about the way in which concepts or categories are explained, and the ways in which knowledge around this idea is constructed. While for Sassen (2014), this involved a de-theorisation of concepts before the disciplining of method, we reflect on the ‘the space before’ as a critical phase to ‘disrupt’ normative linear fast-paced research, foster relationships and allow for new possibilities. We also extend the concept to include the ‘space beyond method’—that is the time and resources necessary to either sustain the research relationship, or exit meaningfully.

Common to all cases was the significant amount of time required before the implementation of method. This variously involved hanging out, ‘chilling’ and informal or messy conversations. Within participatory research projects relationships building prior to the research commencing ‘properly’ is not uncommon, and indeed, such activity can be considered the ‘bread and butter’ of ethnographic and community-based methods. We argue that these activities can be underfunded and the significant time researchers invest in this type of work often goes unrecognised. While this time, to some extent, was built into the doctoral research (cases 1 and 3), the eNurture study (case 2) required a pre-application consultation. This activity became critical to the success of the research, but as noted was unfunded and unresourced. What we see across all three cases is that dedicated time to build relational spaces is not just crucial for ethical and respectful practice but for delivering research impact. Certainly, in our experience, it was often in these spaces that the greatest creativity, energy and meaning was evoked.

To push Sassen's metaphor further, these were also spaces that did not just exist before method, but were also ‘betwixt and between’. For Davidson, this meant time spent throughout the research hanging out at the youth club or bumping into someone in the street on the way home. For Wright, it involved the ‘messy’ and playful conversations between more structured sessions. For these interactions to take place, researchers need more of the thing they lack the most—time. While both Davidson and Wright reflected on past PhD work where there was greater flexibility in how time was spent in the field, this is often not the case in more traditional grants and research. This points to the need to have time built into research grants that can accommodate messiness, re-direction and quiet points of reflection both before, during and after the project formally ends. Planned endings—although not discussed in our cases—are vital for ensuring individuals, groups and communities do not have expectations raised and as a consequence feel their own sense of epistemic injustice (as in Roesch-Marsh's case the group were worried that she was just another researcher coming to ‘consult’ with them).

What we found emergent from these liminal spaces was the potential for small ripples to form ‘beyond method’. Such examples include the young people in Davidson's research working with a local artist to prepare their exhibition, something that they had previously never had the opportunity to do, and for many, represented the first time their voices had been shared with adult professionals. In Roesch-Marsh's work, it is the small local advisory group shaping the production of an animated film that will train social workers and improve future practice. Finally, in Wright's case, we see the Emerging Researchers engaging in active dialogue about inequality and activism, discussions that have the potential to shape their own future activism. In these ripples, we see the relationship between our work and activist research. As we have discussed, activism can look and feel different, in different contexts. Importantly, it can be small, private and quiet. For each case, we might describe the interactions taking place as occupying the ‘space before activism’. Like the space before method, this is a zone in which ideas, taken–for-granted assumptions and normative behaviours can be discussed, challenged and perhaps, transformed in a way that benefits social change. Even in the case of Davidson's research, where engagement with marginalised young men was challenging, spaces were found that recognised and prioritised views previously unheard. But it also provided—in the smallest of ways—space for behaviour negatively affecting a community to be discussed and challenged in a supportive environment.

Relationships were crucial for the creation and sustainability of these spaces. Relational approaches to research emphasise the importance of building bridges between the researcher and participant. Knowledge is produced together and ‘what is revealed emerges out of a constantly evolving, negotiated, dynamic, co-created relational process to which both researcher and participant co-researcher contribute’ (Finlay, 2009, p. 2). The work to establish trust, safety and rapport is essential for this type of research to be possible. In a similar way, relational activism, as we have discussed, emphasises ‘the acts behind activism’, including bridge-building activities in the private sphere which foster trust, emotional ties and comradery in communities and between activists (O'Shaughnessy & Kennedy, 2010). This approach also asserts that ‘relationships have greater agency than individual actors’ and that large-scale change can only be achieved collectively (O'Shaughnessy & Kennedy, 2010, p. 555).

Participatory research at the earlier point in the continuum, we suggest, can foster space for dialogue to emerge for things that could potentially be a form of activism, or become such later. Nielson and Jörgensen (2018) point to the importance of reflecting on the need to be a responsible methodologist, and recognising both the limits of activist research and the power that research can have without explicit activism. Speed (2006) has suggested that activist researchers are not critiqued for failing to sustain critical analysis or ‘objectivity’, but rather because they become too centred on immediate political objectives (p. 73). For Nielson and Jörgensen (2018), this can result in researchers missing opportunities to contribute to longer-term social transformation, or indeed, being able to provide new explanatory frameworks that expose deeper forms of power and injustice. This is not unlike the type of objective that Sassen (2014) set out to expose in her ‘space before method’. More broadly, within this space, there is an opportunity for us to all slow down and have more time to consider more complex aspects of social life. As Davidson's case reveals power is always present, and by involving one group you may be inculcated in the silencing of another. This encourages us to trouble and (re)consider normative understandings of participatory methodologies and young people's activism, through critical exploration of practice. Through this practice, we maintain our responsibilities as methodologists.

Our final concluding point relates to our roles as researchers within higher education. We are mindful of our power (and lack of power) and privilege as early and mid-career female researchers in permanent positions within Russell Group University. Our reflective practice may therefore bring an idealism about what we wish to achieve for the Hub's vision of positive social change and human flourishing that is rooted in and against the institutional space we operate in. As researchers committed to ‘the space before/beyond method’ and ‘the space before/beyond activism’, it is challenging when we do not have time to invest in new research relationships or are unable to maintain relationships when funding ends. It is also vexing when ‘research excellence’ renders relational activities less important, or worse, invisible within academic criteria and progression. Nonetheless, our privileged positioning can also be used to create space, as it has already begun to do so with more prioritisation of participatory research and co-production within research strategies, to trouble the constraints of the academy and hold space for participants and co-researchers to creatively move diverse forms of research and activism forward. We recommend greater individual and collective action across academic spaces to value and allow for slow processes, the possibilities of what may arise, and the beauty of non-action activism. Our work shows the importance of time (planned and unplanned), resources and slow processes. It acknowledges the ‘action’ that can come from the space before-activism and participatory research and the possibility that the small, quiet ripples might travel beyond and affect long-lasting transformation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The empirical data for this article is developed in the research projects The Everyday Day Antisocial funded by an Economic Social Research Council grant (ES/F032013/1); A Play-based Research Approach: Young Researchers' Conceptualisations, Processes, and Experiences funded by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and the University of Edinburgh; and Care leaver relationships, mental health and online spaces funded by eNurture and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Grant reference: ES/S004467/1. Thank you to all the young people and practitioners who were involved in the research projects, and contributed their enthusiasm, knowledge and insight. We are indebted to the Binks Trust who have generously provided funding to establish the new Binks Hub at the University of Edinburgh. Thanks also to our colleagues within the Childhood & Youth Studies Research Group at Moray House School of Education who made this special issue a reality, and the editors and reviewers whose comments helped refine our work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There is no conflict of interest to disclose from any author.

Endnotes

Biographies

Emma Davison is a lecturer in Social Policy and Qualitative Research Methods, University of Edinburgh. Her research focuses on youth transitions and the social infrastructures that support community belonging. Emma is a co-director of the Binks Hub which is delivering a programme of co-creative community research at Edinburgh.

Laura Wright is a Lecturer Childhood Studies, University of Edinburgh. Laura's research and practice with children, youth, and adults over the last 15 years has focused on play- and arts-based participatory methodologies, children's meaningful participation, intergenerational partnerships, children's rights, child protection, and psychosocial well-being.

Autumn Roesch-Marsh is a senior lecturer in Social Work at the University of Edinburgh. A trained social worker, Autumn's research focuses on the needs of people with care experience and the theoretical models that drive social work decision-making. Autumn is a co-director of the Binks Hub which is delivering a programme of co-creative community research at Edinburgh.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.