Assessing motivational interviewing integrity in the Toddler Oral Health Intervention study

Clinical trial registration: The trial is registered in the Dutch Trial Register (www.onderzoekmetmensen.nl): Trial NL8737.

Abstract

Objectives

The Toddler Oral Health Intervention (TOHI) was launched in 2017 to promote oral health prevention at well-baby clinics, with a focus on parents with children aged 6–48 months. This study aims to evaluate the integrity of motivational interviewing (MI) as one of the core intervention pillars in the TOHI study.

Methods

The TOHI study was conducted at nine well-baby clinics in the central and southern regions of the Netherlands, with 11 trained oral health coaches (OHCs) delivering a tailored individual counselling programme. Audio recordings of counselling sessions were uploaded by the OHCs into an online portal for feedback and integrity evaluation purposes. A trained independent assessor evaluated MI integrity using the MITI 4.2.1 coding scale. IBM SPSS Statistics was used to analyse the data, with ratings on technical and relational components and behavior counts computed by adding up the scores and categorizing them into six key MI skills. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages and median scores with interquartile ranges, were calculated.

Results

The median ratings on the technical and relational components were 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.5) and 3.5 (IQR 3.0–4.0) out of a maximum of 5, with 45% and 58% of recordings showing fair or good MI integrity, respectively. A median of 38% (IQR 25–55%) of complex reflections and a reflection-to-question ratio of 0.7 (IQR 0.4–1.0), with 47% and 24% of recordings showing fair or good MI integrity, respectively. Median counts of MI-adherent and non-adherent statements were 3.0 (IQR 2.0–5.0) and 0.0 (IQR 0.0–1.0), respectively. The duration of recordings and MI integrity varied among oral health coaches.

Conclusion

Overall, this study revealed that, while intensive training was provided, not all OHCs in the TOHI study met fair thresholds for MI integrity. These findings emphasize the necessity of ongoing training, reflection and support to achieve and maintain a fair or good level of MI integrity in clinical practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Early childhood caries (ECC) is defined as the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), missing or filled (due to caries) surfaces in any primary tooth of a child under the age of 6 years.1 Despite being preventable, ECC poses a significant health concern, affecting nearly half of preschool-aged children globally.2 In the Netherlands, approximately 30% of 5-year-old children suffer from caries.3 Even though parents' mandatory health insurance covers oral healthcare for children up to 18 years, most children under four do not visit an oral health professional.4 While oral health professionals face challenges in reaching very young children, over 90% of newborns up to the age of four receive regular preventive care and vaccinations at well-baby clinics. Oral health promotion and referrals to oral health professionals are also included in preventive care at these well-baby clinics. However, in practice, insufficient attention is given to oral health promotion.5

The Toddler Oral Health Intervention (TOHI) was launched in 2017 to promote oral health prevention at well-baby clinics.6 As TOHI integrates various existing healthcare components and operates at different organizational levels, it qualifies as a complex intervention according to the definition of the Medical Research Council.7 The impact of TOHI on the cumulative incidence of caries was investigated through a pragmatic multicentre randomized controlled trial, which followed 402 children from 6 months to 4 years of age.6 TOHI comprised an individual counselling programme that was delivered by trained oral health coaches (OHCs), with motivational interviewing (MI) as one of the core intervention pillars. MI is a guiding style designed to address a client's ambivalence about behavior change and enhance intrinsic motivation to do so.8, 9 Beneficial effects of using MI compared to care-as-usual or information-only control groups across various problem behaviors and healthcare settings, including prevention of ECC, are reported.10-15 However, the literature indicates significant variations in its effects across studies, sites and even therapists.10, 15, 16 Therefore, having insight into adherence to the MI protocol is crucial for better understanding the trial's outcomes.

The increasing use of MI in clinical care and research highlights the crucial need for greater attention to assessing adherence to the MI protocol, also referred to as MI integrity, which is one of the proposed dimensions of treatment fidelity.17 Treatment fidelity refers to the extent to which an intervention is implemented as intended, facilitating informed evaluations of its effectiveness and supporting the translation of behavioral interventions from research to clinical practice.17, 18 When applying an intervention, several circumstances can arise from deviation from the intended intervention as per the underlying theory and concept. It has been proposed to assess treatment fidelity based on four dimensions: adherence, dosage, exposure and quality (Table 1).17 MI research frequently addresses MI integrity, which corresponds closely to dimension 4 of fidelity, concerning the quality of intervention steps implemented.19

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Dimension 1. Adherence | The extent to which the intervention steps were implemented as planned |

| Dimension 2. Dosage | The frequency with and duration for which an intervention was delivered |

| Dimension 3. Exposure | The frequency with and duration for which a recipient received the intervention |

| Dimension 4. Quality (integrity) | How well intervention steps were implemented |

The TOHI employed MI as a critical pillar for oral health prevention. While MI's benefits are widely recognized, there is a noticeable lack in research assessing MI integrity, particularly in the setting of pragmatic trials preventing ECC. MI integrity is essential for interpreting the outcomes of interventions and their subsequent translation to clinical practice. Notably, few studies have focused on MI integrity in caries prevention interventions for young children.19-25 Given this context, our study aimed to evaluate MI integrity in the TOHI study.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

This evaluation of MI integrity formed part of the TOHI study, a two-arm pragmatic multicentre randomized controlled trial, was conducted with adherence to established reporting guidelines (Appendix S1). The primary outcome was the cumulative caries incidence at 4 years of age. A detailed trial design and protocol description have been published elsewhere.6 Therefore, this section only covers relevant details related to the fidelity study. The Medical Ethics Research Council of the University Medical Centre Utrecht approved the TOHI study on 20th May 2017 (registration number NL60021.041.17; file number 17-133/D). The trial is registered in the Dutch Trial Register (www.trialregister.nl): Trial NL8737.

2.2 The Toddler Oral Health Intervention

The TOHI study was conducted at nine well-baby clinics in the central and southern regions of the Netherlands. The trial enrolled 402 parent–child dyads aged 6–12 months, with a 1:1 allocation, between June 2017 and June 2019. In both the intervention and control groups, all dyads received preventive healthcare at well-baby clinics, as stipulated by the Public Health Act 2008, with approximately 13 appointments between birth and the age of 4 years.20 The objectives of this preventive child healthcare programme are to monitor growth and development, detect health and social problems (or risk factors) at an early stage, including oral health, screen for metabolic diseases and hearing in newborns,21 implement the national vaccination programme and provide health advice and information. Parent–child dyads in the intervention group were offered TOHI, in addition to the regular well-baby clinic programme, at ages 6 or 8, 11, 15, 18, 24, 30, 36 and 42 months of age. The child's individual caries risk determines the number of appointments, with approximately five to eight appointments between 6 months and 4 years of age. These appointments lasted between 10 and 20 min and were conducted face-to-face with an OHC. These appointments followed a standardized protocol in which OHCs addressed age-related oral health topics, identified the child's caries risk using the Non-Operative Caries Treatment and Prevention (NOCTP) method,22 and assessed the stage of behavioral change concerning basic oral health guidelines according to the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) model.23 As necessary, during the motivational phase, the OHC focused on increasing parents' awareness, risk perception and self-efficacy. When the intention for the behavior was already present, the parent and OHC developed a health plan for the subsequent period, emphasizing action planning and coping planning. MI was used in both phases to explore motivation, ambivalence, barriers and facilitators towards achieving the desired behavior or goal.6

2.3 Interventionists and training

The OHCs involved in TOHI were oral healthcare professionals with a prevention-focused mindset and a background in dentistry, including nine dental hygienists, one dental assistant and one dentist. They had received training in the NOCTP method before and during the intervention including basic principles of MI, and had extensive experience in paediatric dentistry. All OHCs received training in TOHI from the principal investigator and MI training from an experienced MI trainer who was not further involved in the study. These trainers were well-versed in teaching oral health professionals and students in the NOCTP method, HAPA and MI. The OHCs attended the training, which was given after working hours, on a partly voluntary basis. During these training sessions, the focus was on recognizing the stages of behavioral change, tailoring the intervention to the appropriate behavior constructs according to HAPA, and developing advanced MI skills. Learning these skills is an ongoing process that requires time and dedication. Therefore, the training involved a mix of theory and practical examples of (complex) cases by the OHCs, peer feedback and role plays. During the sessions audio recordings from participants were used as teaching material, and were discussed. In this a normative approach was avoided; an interactive and participant-driven approach was used. This to ensure that all participants remained engaged and were able to benefit from each training session. The initial training was held before the start of the intervention and followed up every 3–4 months over the 4-year study period. In total, there were 11 3-hour sessions. Two OHCs started after the first four sessions and attended all subsequent trainings. Four OHCs missed two training sessions and one OHC missed one. All training sessions were video recorded, and OHCs who missed a training were asked to study the video recording. In addition, the MI trainer provided individual feedback on self-recorded audio recordings submitted by the OHCs.

2.4 MI integrity assessment

The OHCs were made aware of the crucial role of regularly recording their intervention sessions for self-evaluation, training purposes and the reporting on MI integrity. The OHCs were requested to upload audio recordings with permission from the parent–child dyads into the online portal before each training session for feedback purposes. To harness against a skewed and pleasing selection of recordings, OHCs were guided to choose a diverse range of recordings from both routine and challenging sessions. To evaluate the MI integrity in the TOHI study, an independent assessor, unaware of the OHCs' identities, evaluated all the audio recordings using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) 4.2.1 coding scale.19 This evaluation was conducted before the outcome evaluations, ensuring that the analysis was fully blinded and not influenced by the results of the effect study.

2.5 Training of the MITI coder

Previous research had demonstrated that individuals with little experience in MITI coding could be trained with 40 h of instruction.24 In this study, a junior researcher with a dental background (EV) was trained in MITI coding by two MI experts who were not involved in the TOHI study. The three of them had weekly meetings for a month, which included reviewing theory after self-study, practising coding and discussing independent assessments of audio recordings until they reached a consensus on coding. This training equated to approximately 40 h, including self-study and meetings. Each independent rating of the audio recordings was accompanied by observation notes and quoted excerpts to facilitate discussion and consensus. A consensus was established upon coding and analysing three audio recordings, and the junior researcher was tasked with coding the remaining recordings. The three recordings used for training were incorporated into the analysis. In order to continue coding the remaining recordings, observational notes were taken, allowing the researcher to seek consultation with one of the two MI experts to clarify any doubts if consensus was needed.

2.6 MITI 4.2.1 coding scale

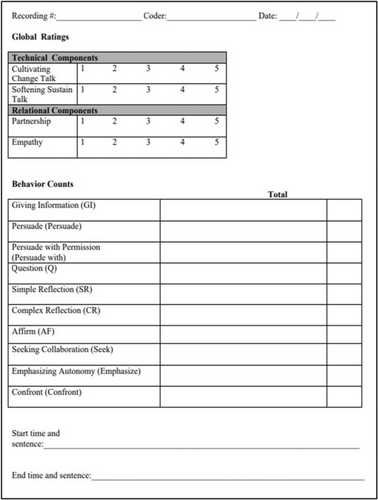

The MITI 4.2.1 coding scale (Figure 1) was utilized to assess the MI integrity of interventionists. This coding scale was developed in 2014 and assesses the presence of crucial MI skills. Several studies have evaluated MITI 4.2.1, demonstrating its reliability and validity in measuring MI integrity in various countries and settings.19, 25, 26

The MITI comprises two ratings: the technical and the relational rating, which are classified as ‘global ratings’, because they aim to provide a global impression of MI integrity. The technical rating assesses how well the interventionist uses MI skills such as open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries to encourage change talk (reinforcing the client's reasons and need for change) and soften sustain talk (exploring the client's reasons for maintaining current behavior). The relational rating measures the quality of the interventionist's relationship with the client, including partnership and empathy. Partnership evaluates how well the interventionist and client work together as equals in the change process. At the same time, empathy refers to the interventionist's ability to reflect on the client's statements or motivations in a supportive and non-judgmental manner. Each rating ranges from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating stronger adherence to MI integrity.

In addition to the global ratings, MITI includes 10 behavior counts that provide specific information about how frequently the interventionist uses MI skills (Figure 1). Behavior counts offer a more nuanced understanding of the interventionist's behavior. Within the behavior counts, there are two types: MI adherent behavior counts and MI non-adherent behavior counts. MI adherent behavior is consistent with the principles of MI. It includes skills such as affirming, seeking collaboration, emphasizing autonomy, persuading with permission, asking open and closed questions and providing simple and complex reflections. MI non-adherent behavior is not consistent with the principles of MI and includes persuading without permission and confronting. A full description of the ratings and behavior counts, including example sentences, can be found in Appendix S2.

2.7 Handling and recoding of data

After coding, the data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28.0). The global ratings and behavior counts were computed by adding up the scores and categorizing them into six key MI skills (Table 2). The MITI provides three levels of MI integrity—‘insufficient’, ‘fair’ and ‘good’—for four MI skills, including the technical component, the relational component, the percentage of complex reflections and the reflection-to-question ratio (Table 1).

| MI skills | Levels of MI integrity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient | Fair | Good | |

| Technical component rating (max. score 5) ((cultivating change talk + softening sustain talk)/2) | <3 | ≥3 | ≥4 |

| Relational component rating (max. score 5) ((partnership + empathy)/2) | <3.5 | ≥3.5 | ≥4 |

| Percentage of complex reflections (complex reflections/(simple reflections + complex reflections)) | <40% | ≥40% | ≥50% |

| Reflection-to-question ratio (total reflections/total questions) | <1:1 | 1:1 | 2:1 |

| MI adherent statements (seeking cooperation + affirming + emphasizing autonomy) | Number of MI adherent statements varies with recording length and conversation context and needs balance | ||

| MI non-adherent statements (confronting + convincing) | Number of MI non-adherent statements should be limited | ||

2.8 Analysis of MI fidelity

The collected data were analysed using descriptive statistics to evaluate MI integrity. Distributions, including the frequencies of audio recordings, means with standard deviations (SD) for audio recording duration and median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for all MI skill ratings (Table 2), were tabulated separately and collectively for OHCs.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Audio recordings

In this study, 62 audio recordings were gathered from 11 OHCs across the nine participating well-baby clinics. After removing audio recordings with incorrect or unusable file formats (n = 4) or excessive background noise (n = 3), 55 audio recordings were included in the analysis. The audio recordings' mean (SD) duration was 17.2 (±6.5) minutes, with the most extended recording and MI intervention lasting 48.5 min and the shortest recording lasting 3.2 min. Approximately, half of the included audio recordings (n = 29) were taken during the first four sessions with the OHCs (child's age between 6 and 18 months), while the remaining recordings (n = 26) came from the last four sessions (child's age between 24 and 42 months). Among the recorded parent–child dyads, 58% concerned the first child in the family and 71% belonged to families with a high socio-economic position. For the total TOHI study sample, 61% concerned the first child in the family and 71% belonged to families with a high socio-economic position.

3.2 Global ratings

Table 3 presents the global ratings, with the technical component having a median rating on a collective level of 2.5 (IQR 2.0–3.5). In 25 (45%) out of the 55 recordings, a fair or good level of MI integrity (rating ≥ 3.0) was achieved. On a collective level, the relational component had a median rating of 3.5 (IQR 3.0–4.0), and in 32 (58%) out of the 55 recordings, the threshold for a fair or good level of MI integrity (rating ≥ 3.5) was met.

| OHC 1 | OHC 2 | OHC 3 | OHC 4 | OHC 5 | OHC 6 | OHC 7a | OHC 8a | OHC 9 | OHC 10 | OHC 11 | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of recordings | 9 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 55 |

| Duration of audio recording in minutes, mean (SD) | 18.2 | 17.5 | 17.3 | 15.4 | 18.1 | 16.3 | 34.2 | 16.1 | 19.3 | 10.0 | 18.4 | 17.2 |

| (4.5) | (2.2) | (5.2) | (1.2) | – | (3.4) | (20.2) | (0.5) | (6.5) | (4.3) | – | (6.5) | |

| Technical component rating | 3.0 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| (2.5–3.3) | (2.0–2.3) | (2.5–3.5) | (2.0–3.4) | – | (2.8–4.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–3.5) | (2.0–2.3) | – | (2.0–3.5) | |

| Cultivating change talk | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| (2.5–3.5) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–4.0) | (2.0–3.0) | – | (3.0–4.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–3.0) | 2.0–2.5) | – | (2.0–3.0) | |

| Softening sustain talk | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| (2.5–3.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (3.0–3.0) | (2.0–3.8) | – | (2.8–4.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (2.0–2.0) | – | (2.0–3.0) | |

| Relational component rating | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| (3.5–4.0) | (2.5–3.0) | (3.5–4.0) | (3.0–4.0) | – | (3.8–4.0) | (2.5–3.0) | (2.5–3.0) | (3.0–4.0) | (2.6–3.0) | – | (3.0–4.0) | |

| Partnership | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| (3.0–4.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (3.0–4.0) | (3.0–4.0) | – | (3.8–4.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (3.0–4.0) | (2.3–3.0) | – | (3.0–4.0) | |

| Empathy | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| (4.0–4.0) | (3.0–3.0) | (4.0–4.0) | (3.0–4.0) | – | (4.0–4.0) | (3.0–3.0) | (3.0–3.0) | (3.0–4.0) | (3.0–3.0) | – | (3.0–4.0) |

- Note: N.B. Variables are noted as median (IQR: 25th, 75th quartile). Bold values represent the calculated scores for MI skills of interest as proposed by MITI 4.2.1.

- a 25th and 75th percentiles for OHC 7 and 8 are calculated with Tukey's hinges.

3.3 Behavior counts

Table 4 shows the number of behaviors and the calculated scores for MI skills. For complex reflections, 26 (47%) of the 55 audio recordings met the threshold for a fair or good level of MI integrity (score ≥40%), resulting in a median score of 38% (IQR: 25–55%) on a collective level. The reflection-to-question ratio met the threshold for a fair or good level of MI integrity (score ≥1.0) in 13 (24%) of the 55 recordings, resulting in a median score of 0.7 (IQR: 0.4–1.0) on a collective level. The median count of MI-adherent statements was 3.0 (IQR 2.0–4.5), and non-adherent statements were minimal, with an overall median count of 0.0 (IQR 0.0–1.0) collectively.

| OHC 1 | OHC 2 | OHC 3 | OHC 4 | OHC 5 | OHC 6 | OHC 7a | OHC 8a | OHC 9 | OHC 10 | OHC 11 | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of recordings | 9 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 55 |

| Duration of audio recording in minutes, mean (SD) | 18.2 | 17.5 | 17.3 | 15.4 | 18.1 | 16.3 | 34.2 | 16.1 | 19.3 | 10.0 | 18.4 | 17.2 |

| (4.5) | (2.2) | (5.2) | (1.2) | – | (3.4) | (20.2) | (0.5) | (6.5) | (4.3) | – | (6.5) | |

| Behavior counts | ||||||||||||

| Giving information | 5.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| (4.0–8.0) | (6.5–14.0) | (5.0–8.0) | (2.3–5.0) | – | (2.0–4.3) | (2.0–5.0) | (5.0–6.0) | (5.0–9.0) | (2.5–5.8) | – | (4.0–7.0) | |

| Persuade | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–2.0) | (0.0–0.0) | – | (0.0–2.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.8–2.3) | (0.0–0.8) | – | (0.0–1.0) | |

| Persuade without permission | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| (0.0–1.5) | (0.0–0.5) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–1.0) | – | (0.0–1.3) | (1.0–2.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–0.0) | – | (0.0–1.0) | |

| Questions | 5.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 |

| (4.5–7.00 | (4.0–8.0) | (7.0–8.0) | (7.3–10.8) | – | (5.0–10.3) | (5.0–6.0) | (5.0–6.0) | (4.8–7.0) | (6.8–11.0) | – | (5.0–8.0) | |

| Simple reflection | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| (2.0–4.0) | (2.0–4.0) | (2.0–6.0) | (2.3–3.0) | – | (2.0–5.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (2.0–3.3) | (2.0–4.8) | – | (2.0–4.0) | |

| Complex reflection | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| (0.5–3.0) | (0.5–2.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (1.0–2.8) | – | (2.0–3.0) | (0.0–2.0) | (2.0–2.0) | (1.0–3.0) | (1.0–2.0) | – | (1.0–3.0) | |

| Affirm | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| (0.0–1.5) | (1.0–2.0) | (1.0–1.0) | (2.3–3.0) | – | (0.0–1.5) | (1.0–3.0) | (1.0–1.0) | (1.0–1.3) | (1.0–3.5) | – | (1.0–2.0) | |

| Seeking collaboration | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| (0.5–3.0) | (1.0–1.5) | (2.0–4.0) | (1.0–2.8) | – | (1.8–6.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (1.0–3.0) | (1.0–1.0) | – | (1.0–3.0) | |

| Emphasizing autonomy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0,0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.5) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–0.0) | – | (0.0–2.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (1.0–1.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | – | (0.0–0.0) | |

| Confront | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | – | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.0–0.0) | – | (0.0–0.0) | |

| Percent complex reflections | 38% | 33% | 33% | 33% | NA | 44% | 25% | 45% | 50% | 27% | NA | 38% |

| (17–50) | (17 –37) | (30–50) | (25–55) | (35–63) | (0–50%) | (40–50) | (30–53) | (18–50) | (25–55) | |||

| Reflection: question ratio | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| (0.6–1.3) | (0.6–0.8) | (0.6–1.3) | (0.4–0.7) | – | (0.5–1.1) | (0.4–1.0) | (0.8–0.8) | (0.4–1.2) | (0.4–0.7) | – | (0.4–1.0) | |

| MI-adherent statements | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| (1.0–4.0) | (2.0–3.5) | (3.0–5.0) | (4.0–5.0) | – | (3.9–6.3) | (3.0–3.0) | (2.0–3.0) | (2.0–4.0) | (1.3–5.0) | – | (2.0–5.0) | |

| MI-nonadherent statements | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| (0.0–1.5) | (0.0–0.5) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–1.0) | – | (0.0–1.3) | (1.0–2.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–1.0) | (0.0–0.8) | – | (0.0–1.0) |

- Note: N.B. Variables are noted as median (IQR: 25th; 75th quartile). Bold values represent the calculated scores for MI skills of interest as proposed by MITI 4.2.1.

- a 25th and 75th percentiles for OHC 7 and 8 are calculated with Tukey's hinges.

4 DISCUSSION

This research aimed to evaluate MI integrity as a dimension of treatment fidelity in the context of the TOHI study. The findings of this study revealed a considerable range of MI integrity among OHCs, with approximately half of the audio recordings assessed achieving a fair or good level of MI integrity based on the rating of the technical component and the behavior counts measured with the MITI 4.2.1. In addition, most of our OHCs scored fair to good on the relational component. Furthermore, all OHCs exhibited MI adherent and minimal MI non-adherent statements, indicating a fundamental level of MI integrity.

Despite increasing publications on MI interventions in oral healthcare, MI integrity has rarely been explored. So far, most evaluations of MI have primarily focused on outcomes. To date, seven studies have evaluated MI integrity in the context of preventive oral healthcare interventions in high caries-risk populations in America, Australia and Brazil.27-33 However, comparing the results of these studies is challenging due to variations in the populations studied and the different instruments employed to assess MI integrity. The MITI emerged as the most commonly utilized instrument; however, five studies incorporated an older version of the MITI (3.1.1),27-31 which only provided a single global score. In contrast, the later version, MITI 4.2.1, offers two global ratings: one for the technical component and one for the relational component. Most interventionists in these studies met the fair threshold on the global rating, with average scores between 3.4 and 4.3. The study by Ismail et al.30 was an exception, with 43% of counsellors achieving the fair threshold and 26% reaching the good threshold for MI integrity, but no further details were provided. Like us, Leske et al.32 had utilized the MITI 4.2.1 for assessing MI integrity; however, unlike our study, all interventionists in their study achieved scores above the fair threshold for technical and relational components. Weinstein et al.33 utilized the Yale Adherence and Competence Scale, and found an adequate overall score for MI integrity for al interventionists. None of the studies that used the MITI reached the fair threshold for the reflection-question ratio, and in only three studies, the majority of interventionists achieved the fair threshold for the percentage of complex reflections, which is consistent with our findings.27, 28, 31

In the TOHI study OHCs were provided with similar training methods as in previous studies,27-33 consisting of approximately 33 h of training in 11 sessions at 3–4 month intervals, incorporating theory, self-reflection, individual feedback on audio recordings and role plays. However, there were also some notable differences in the training approaches. For instance, most studies had a higher follow-up rate during the first months, conducted integrity assessments before the intervention, had smaller training groups, and recorded nearly all conversations to assess MI integrity and provide structured feedback. These differences may imply that appropriate training strategies and structured feedback are critical in attaining and sustaining MI integrity and may have influenced the results of our study.

When interpreting the findings of this study, the following limitations should be considered. First, evaluating MI integrity is a complex process that requires a significant investment of time and resources and a concerted effort from interventionists to obtain participant consent for the recording and ensure that all recordings comply with General Data Protection Regulation guidelines. Given the large number of interventions with parent–child dyads in our study (>1000) and the study duration, recording all interventions to select a random sample for MI integrity assessment was deemed disproportionate. As TOHI was a pragmatic trial involving oral health professionals who participated partly voluntarily rather than employing professional research staff, as in other studies, the study's burden was minimized to facilitate collaboration. In this context, the audio recordings for our study were primarily intended for the training of OHCs and to standardize the delivery of the TOHI in accordance with the published study protocol.6 Consequently, the method of collecting recordings was non-systematic and may have introduced selection bias. The pragmatic nature of the trial, coupled with the initial intention for the recordings to serve training purposes, led to the absence of a formal pre-training assessment of the OHCs' MI skills. This omission prevented a direct evaluation of the training's impact on these skills, representing an additional limitation.

A second limitation is the absence of measured agreement between the MITI coder and the trainers. Nevertheless, the rigorous training the junior researcher underwent should be recognized. Spanning approximately 40 hours and guided by two MI experts, the training encompassed self-study, practice coding and consensus-building on audio recordings. Observation notes and consultations with MI experts should have reinforced the accuracy of the coding process by the junior researcher, aligning with established research recommendations.24

Third, the conduct of the TOHI study was significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic over 2 years, consequently impacting the study's results on MI integrity on three points: (1) the pandemic caused delays and disruptions in multiple TOHI interventions, which were postponed or carried out using alternative methods such as telephone consultations; (2) training sessions with OHCs were postponed and rescheduled later via online meetings; and (3) the study took longer, and some of the primarily voluntary participating OHCs changed jobs. New OHCs replacing them started without the full initial training. These three points may have led to an altered interaction with parent–child dyads, challenges and barriers to audio recordings, resulting in fewer recordings, less self-reflection and, therefore, lower scores on MI integrity.

A final limitation relates to the MITI. While MITI 4.2.1 is currently the most widely used instrument for assessing MI integrity, it has some shortcomings. Its primary focus is evaluating the interventionist's MI integrity without fully capturing the client's perspective, experiences or reactions, which may result in an incomplete understanding of the intervention's impact. Additionally, the duration of audio recordings also plays a significant role in the assessment, with longer sessions generally receiving higher scores for MI integrity.26 Highly motivated parent–child dyads in the TOHI study may have limited opportunities for behavioral change, especially after attending multiple OHC sessions. Consequently, shorter sessions offer fewer opportunities to display MI skills, potentially leading to reduced behavior counts and lower scores.

In conclusion, notwithstanding this study's limitations, it substantially informs the interpretation of TOHI study outcomes and the implications for implementing TOHI in oral practice upon proven effectiveness. TOHI is a complex health intervention, with MI being just one intervention component. Therefore, ensuring integrity across all other intervention components (NOCTP and HAPA) and fidelity concept elements is crucial for a comprehensive understanding. This study reveals that not all OHCs in TOHI met the fair MI integrity thresholds but performed well on the relational component, which is essential when targeting parents of young children.

Although the precise level of MI integrity necessary to effectively influence behavior remains unknown at present,31, 34 the results of this study highlight the difficulty of achieving sufficient MI integrity. Some studies point to differences in results in the impact of caries prevention when the professional who delivers MI is not an oral health professional.15, 34 In our study, we exclusively employed highly motivated and extensively trained oral health professionals as OHCs, predominantly dental hygienists. This choice was not only motivated by the pragmatic nature of our study but also because these professionals are the most logical choice within our oral healthcare system to serve as OHCs. This strategic choice, alongside the extensive training they received and our study's findings, prompt us to reflect on what to expect from the dental field regarding the implementation of MI interventions like TOHI, as well as the extent of effort required to develop and maintain adequate MI skills. Employing systematic feedback and self-reflection, with tools like MITI 4.2.1, can enhance MI integrity and ensure long-term consistency. This approach enables trainers to assess, guide, and support oral health professionals in implementing MI interventions more effectively, potentially leading to better patient outcomes.35-38 However, realizing these benefits necessitates a commitment to training that extends beyond the conventional single session followed by a 1-day follow-up, highlighting the need for a substantial investment in professional development.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PCJMvS, CvL and KJC: Idea and concept of study. PCJMvS, EV and JB: Design, methodology and protocol of study. PCJMvS, CvL, GJMGvdH and KJC: Acquisition of study funding. PCJMvS: Acquisition of study data. EV and JB: Management and cleaning of study data. EV, JB and PCJMvS: Analysis and interpretation of study data. EV, JB and PCJMvS: Preparing draft of manuscript. PCJMvS, CvL, GJMGvdH and KJC: Critical revision of manuscript draft. PCJMvS, EV, JB, KJC, JMGvdH, and CvL: Final approval for publication of manuscript. PCJMvS, JB and KJC: Supervision of study conduct. PCJMvS, CvL, GJMGvdH and KJC: Guarantor of study integrity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all Oral Health Coaches who participated in the TOHI study, as well as MI trainer Ellen Zwart, for their commitment and permission for the anonymized use of the audio recordings. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Nolan Ungerer and Marijke van Es, independent MI experts who contributed to the MITI training and consensus building.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by a grant from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (023.009.044) and by the governing body for practice-based research (Regieorgaan SIA) (RAAK.PUB03.018 and TOPUP.09.022). The funders were not involved in the study design, collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the report or the decision to submit the report for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.