Barriers to and facilitators for creating, disseminating, implementing, monitoring and evaluating oral health policies in the WHO African region: A scoping review

Abstract

Objective

To advance oral health policies (OHPs) in the World Health Organization (WHO) African region, barriers to and facilitators for creating, disseminating, implementing, monitoring and evaluating OHPs in the region were examined.

Methods

Global Health, Embase, PubMed, Public Affairs Information Service Index, ABI/Inform, Web of Science, Academic Search Complete, Scopus, Dissertations Global, Google Scholar, WHO's Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS), the WHO Noncommunicable Diseases Document Repository and the Regional African Index Medicus and African Journals Online were searched. Technical officers at the WHO Regional Office for Africa were contacted. Research studies and policy documents reporting barriers to and facilitators for OHP in the 47 Member States in the WHO African region published between January 2002 and March 2024 in English, French or Portuguese were included. Frequencies were used to summarize quantitative data, and descriptive content analysis was used to code and classify barrier and facilitator statements.

Results

Eighty-eight reports, including 55 research articles and 33 policy documents, were included. The vast majority of the research articles and policy documents were country-specific, but they were lacking for most countries. Frequently mentioned barriers across policy at all stages included financial constraints, a limited and poorly organized workforce, deprioritization of oral health, the absence of health information systems, inadequate integration of oral health services within the overarching health system and limited oral health literacy. Facilitators included a renewed commitment to establishing national OHPs, recognition of a need to diversify the oral health workforce, and an increased understanding of the influence of social determinants of health among oral health care providers.

Conclusions

Most countries lack a country-specific body of evidence to assist policymakers in anticipating barriers to and facilitators for OHPs. The barriers and facilitators relevant to disparate subnational, national, and regional conditions and circumstances must be considered to advance the creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of OHPs in the WHO African region.

1 INTRODUCTION

The burden of oral diseases is a major global public health problem but has long been neglected in global health policies.1 In recent years, achieving better oral health has gained recognition as an essential component of overall health due to its impact on a person's physical, mental and social well-being.2 Common risk factors (e.g. social and commercial determinants of health, unhealthy diets, tobacco and alcohol use) are linked to both oral diseases and other non-communicable diseases (NCDs), highlighting the importance of including oral health in all health policies, NCDs and universal health coverage (UHC) agendas.3, 4 The World Health Organization (WHO) and the FDI World Dental Federation have been advocating for a common risk-factor approach to NCDs and oral diseases, as well as strengthening health systems to achieve UHC for oral health.3-5

Evidence-informed policies can be instrumental in mitigating the neglect of oral health globally, as these policies can improve the efficiency of healthcare systems and the quality of health outcomes.6 However, having evidence-informed policies alone is insufficient. The creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of health policies are often complex processes influenced by a multitude of factors. Successful enactment of OHPs may be hampered by numerous barriers or assisted by a variety of facilitators, highlighting the need for understanding the circumstances that can either hinder or support such policies.

The current oral health status of the population in the African region is alarming and requires urgent action. Approximately 44% of the population in the WHO African Region suffers from oral diseases, and the region has experienced the steepest rise globally in oral conditions over the last three decades.7, 8 Almost half of the countries in the region do not have an oral health policy to guide national efforts,7 and oral health is deprioritized compared to other national health agendas. Oral health workforce shortage is a common problem in most countries in the region and further limits the ability of health systems to provide oral health services.1

The WHO African region encompasses a diverse and dynamic group of nations, with each constituent country having its own distinct characteristics and nuances. Creating, disseminating, implementing, monitoring and evaluating health policies demands a tailored response to unique socio-economic, cultural and health system characteristics. A clear understanding of existing subnational, national and regional factors influencing oral health policies is still needed. This scoping review examines barriers to and facilitators for creating, disseminating, implementing, monitoring and evaluating OHPs in the WHO African region.

2 METHODS

2.1 Protocol registration

The reporting of this scoping review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Table S1)9 and its methodology, a modified version of the Arksey and O'Malley framework.10 A draft of the review protocol is available elsewhere.11

2.2 Eligibility criteria

2.2.1 Inclusion criteria

Documents reporting barriers to and facilitators for creating, disseminating, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating oral health policies (OHPs) in the WHO Africa region were included. Also included were subnational, national, and regional OHPs; clinical practice guidelines addressing oral health issues; national oral health strategies, plans, and documents authored by Ministries of Health personnel and non-governmental agencies focusing on policy, policy briefs and policy analysis. The barriers and facilitators found were either summarized quantitatively or reported as qualitative statements.

Population

Documents that identified the perspectives of a wide array of relevant stakeholders, including policymakers, healthcare managers and administrators, organizational leaders (including non-governmental organization leaders), healthcare professionals, researchers, and citizens, were examined for possible inclusion. In alignment with ‘The Evidence Commission Report: A wake-up call and path forward for decision-makers, evidence intermediaries, and impact-oriented evidence producers’, citizens are defined here as all members of society, such as patients and caregivers, service users, parents, voters, community leaders and workers.12

Setting

The setting for this review included any of the 47 countries of the WHO African Region: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Cote d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia or Zimbabwe.13

Type of evidence

- Research articles (e.g. systematic reviews, scoping reviews, umbrella reviews, primary studies, and conference proceedings) directly assessing barriers and facilitators to the creation, dissemination implementation, monitoring, or evaluation of an OHP in dental clinics, community (e.g. a village, a municipality), district (province or territory), or at a national or regional level, or exploring stakeholders' perceptions, experiences, perspectives, knowledge, or attitudes in relation to the provision of oral health services (financing, access, or provision) across several OHPs, or ascertaining stakeholders' perceptions, experiences, perspectives, knowledge, or attitudes concerning a specific intervention to diagnose, treat, or prevent diseases. These articles had to mention that the intervention and study purpose is connected to or contained within an existing OHP or government program in the WHO African region.

- OHP-related documents addressing barriers and facilitators in the WHO African region had to contain a section or sentence about barriers to and facilitators for OHP creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, or evaluation at a subnational, national, or regional level

2.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Conference abstracts, commentaries, editorials and research protocols, as well as articles that aimed to analyse and report epidemiological data (e.g. prevalence, burden of disease), risk or protective factors for oral diseases, or assessed the effectiveness, safety, or cost-effectiveness of interventions for the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of oral diseases, without reporting any outcome related to barriers and facilitators for OHPs, were excluded. In addition, articles reporting barriers to and facilitators for the creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, or evaluation of OHPs in aggregate for countries within and outside the WHO African region for which data regarding African countries could not be isolated or separated from the aggregated data were excluded.

2.3 Information sources

Two information specialists with extensive expertise in systematic review and health and social science searching created the search strategies for each database in consultation with the project team and subject matter experts. The search strategies were peer-reviewed by information specialists not involved in this project. Electronic databases (Global Health, Embase, PubMed, Public Affairs Information Service Index, ABI/Inform, Web of Science, Academic Search Complete and Scopus) were searched for articles and policy documents published between January 2002 and March 2024. The databases Dissertations Global and Google Scholar were also searched for grey literature. To capture materials produced by the WHO that are not indexed in scholarly databases, additional sources such as WHO's Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS), Google, and WHO Noncommunicable Diseases Document Repository were searched. Technical officers at the WHO Regional Office for Africa were contacted. To ensure materials indexed in African regional databases such as Regional African Index Medicus and African Journals Online were captured, the aforementioned databases were cross-checked to verify coverage (Appendix S1, ‘Sources of references, search strategies, results, and search period’).

2.4 Selection of studies

Pairs of reviewers independently assessed citations' titles and abstracts, as well as full-text reports against eligibility criteria. Research team members with fluency in English, French, and Portuguese reviewed reports in those languages. A third reviewer analysed any discrepancies between pairs and determined final eligibility. The screening and final eligibility of documents were managed in Covidence.14

2.5 Data charting process

A data extraction sheet tailored to the scope of this review was created to capture the following data fields: first author, publication year, type of article, country, setting, group or audience to which the policy was directed, participants' characteristics, document objectives, research methods (for research articles), and key findings. Quantitative and qualitative data was extracted from each document as that data pertained to stakeholders' perceptions and experiences regarding barriers to and facilitators for the creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of OHPs. These data were in the form of participants' quotes, narrative descriptive summaries, author hypotheses, theoretical frameworks, explanations and recommendations, themes, and sub-themes. Data were extracted by one reviewer and verified by another reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion. A third reviewer served as a judge when consensus was not reached.

2.6 Data items

Barriers were defined as any problem—whether practical, political, financial, or technical—that obstructed the creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, or evaluation of an OHP. Facilitators were defined as any entity, process, social movement, technology, legislation, or organizational structure that promoted or optimized any creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, or evaluation of an OHP. Barriers and facilitators were classified according to the OHP process they pertained to: OHP creation referred to how the policy was developed, already in place elsewhere, and adopted in a new setting or adapted for citizens, healthcare personnel, institutions, or organizations in the WHO African region. Examples include articles assessing stakeholder engagement in developing policies, exploring research as a basis for policies, and examining the involvement of policymakers and researchers or others in policy development. Barriers to and facilitators for adopting or adapting an existing OHP or a clinical practice guideline to a different population were also classified in this category.15 OHP dissemination referred to any plans for sharing or promoting the content of the OHP widely to the intended target audiences. Examples of articles addressing OHP dissemination strategies included translating the OHP into multiple languages, mass media strategies, enabling open access to publications containing the policy, and email communications. OHP implementation, monitoring, and evaluation referred to how an OHP is applied at a subnational, national, or regional level, whether an OHP changes health organizations; behaviours of healthcare professionals, patients, or caregivers; or utilization of healthcare services. Examples include articles on integrating essential dental medicines and preparations into the national essential medicine list, implementing school-based and screening programs, utilizing printed educational materials circulated with schools' clinical centres, conducting audits and feedback, setting up reminders, establishing financial incentives, and using computer decision support systems.

2.7 Analysis and synthesis of results

Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize quantitative data. The qualitative data for the barriers and facilitators were coded using ATLAS.ti, and descriptive content analysis was conducted.16, 17 Because this is the first scoping review about this topic in oral health, A two-pronged approach was utilized to create a taxonomy for the barriers and facilitators. First, relevant taxonomies and frameworks were identified. After analysing and comparing the available taxonomies in the literature. An existing taxonomy from a systematic review assessing barriers to and facilitators for health policies outside the field of oral health was selected based on the comprehensiveness of the themes covered.18 Then, in an iterative process, the statements extracted from the included research articles and documents specific to OHPs were coded to refine the taxonomy used in the systematic review cited above.

3 RESULTS

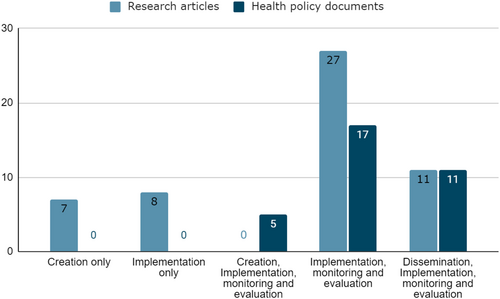

The search identified 7352 records across all information sources. After removing duplicates, the initial eligibility of 6797 records was assessed using titles and abstracts, of which 172 reports were retrieved for full-text screening. Eighty-eight documents, including 55 research articles (53 individual studies; two included studies were reported in two documents), and 33 policy documents proved eligible. (Figure 1, Table S2).

3.1 Characteristics of sources of evidence

Most included research articles were primary studies, with only 17% (n = 9) corresponding to evidence synthesis approaches (e.g. narrative review, systematic review). The primary studies used a combination of qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods approaches; all the studies used a cross-sectional design. The most common measurement tools employed to assess barriers and facilitators included self-administered questionnaires (n = 12, 23%) and semi-structured interviews (n = 12, 23%). The OHPs evaluated in 87% (n = 46) of the research articles had a national scope and primarily examined barriers to and facilitators for OHPs concerning health system interventions or reforms (n = 19, 36%), oral health prevention and promotion (n = 9, 17%), or multiple scopes (e.g. prevention, treatment, diagnosis/screening) (n = 17, 32%) (Table S3).

Among the 33 health policy documents, 85% (n = 28) failed to report a systematic framework to identify and evaluate barriers to or facilitators for OHPs. In other words, barriers and facilitators are presented, but the documents did not report sources or information regarding data collection or synthesis methods. Oral health policy documents mainly employed a regional as opposed to a national and subnational scope, and the scope encompassed health system interventions and reform more frequently than the included research articles (Table S3). South Africa and Nigeria produced more than 43% (n = 37) of the research articles and oral health policy documents in the WHO African region regarding barriers to and facilitators for OHPs, followed closely by multiple other countries in the African region (n = 15, 18%) (Table S4). Health policy documents assessed barriers and facilitators primarily using a multistakeholder approach or prioritizing policy makers' perspectives, as compared with research articles, which used a more fragmented approach—single stakeholder perspectives (healthcare professionals, citizens, healthcare managers and administrators, or policymakers) (Figure S1).

3.2 Barriers to and facilitators for the creation of OHPs

Twelve reports discussing barriers to and facilitators for creating OHPs were identified (Figure 2, and Table S2). The most common type of barrier to creating OHPs identified focused on organization and resources. The included reports mentioned the lack of workforce planning and coordination, the lack of a dedicated oral health department at the Ministries of Health, and the lack of robust health information systems. The reports also identified several facilitators for the creation of OHPs, including increased priority across stakeholders to create national OHPs, increased awareness and relevance of NCDs directly impacting oral health, and the experiences gained by African investigators in participating in international collaborations (Table 1).

| Themes* | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Contact and collaboration | Stakeholders mismatch in regulation and accreditation | Creation of national oral health policies is an increased priority |

|

Breakdown in communication between providers and national authorities Stakeholders' resistance and scepticism Insufficient digital infrastructure for data sharing |

Experience gained from international collaborations Support from WHO for the dissemination of policies External push (international influence to create national or health policies) |

|

| Organization and resources |

Stakeholders lack of workforce planning and coordination Lack of training and consideration of non-dental professionals Poor organizational structure in Ministry of Health Lack of oral health department at Ministry of Health Lack of workforce retention Governance instability Lack of robust health information systems Lack of oral health services at the public sector level Lack of or limited oral health budget at the state level |

Stakeholders willingness to align with international standards Support from the World Bank with funding Refreshed commitment from health authorities to produce oral health policies |

|

Policy characteristics |

Lack of or inefficiencies in planning and managing oral health services Lack of community engagement to address oral health Lack of strategic planning |

Creation of national oral health policies is an increased priority International movement towards oral health policies and evidence-based practices Increased awareness of non-communicable diseases |

| Policymaker characteristics | Stakeholders' resistance and scepticism |

Experience gained from international collaborations Diverse and inclusive stakeholder engagement for policy development |

| Research and researcher characteristics |

Limited access to research evidence and local information Lack of qualified research personnel |

Stakeholders willingness to align with international standards Promote creation of research and policy centers |

| Consumer/patient-related characteristics | Oral health diseases not a priority | Diverse and inclusive stakeholder engagement for policy development |

- * Themes adapted from Oliver and colleagues.18

3.3 Barriers to and facilitators for the dissemination of OHPs

Twenty-two reports discussing barriers to and facilitators for disseminating OHPs were identified (Figure 2, and Table S2). The barriers identified commonly related to organization and resources, including the poor integration of oral health services with the rest of the health system, the lack of a centralized communication strategy to promote oral health, the shortage of educational material, and the lack of training and consideration of non-dental professionals who can serve as promoters of oral health initiatives linked to national OHPs. A limited number of facilitators for the dissemination of OHPs were identified, including the prioritization of interdisciplinary educational interventions, increased public awareness about dental healthcare services, and increased mass media sensitization to health-related topics (Table 2).

| Themes* | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Contact and collaboration |

Poor integration of oral health services Lack of mentorship programs and interdisciplinary professional education |

Prioritization of interdisciplinary educational interventions |

| Organization and resources |

Lack of training and consideration of non-dental professionals Poor integration of oral health services Stakeholders lack of workforce coordination Lack of information of dental clinic location Lack of information on dental visits Shortage of educational material Limited one-on-one oral health education Oral health diseases not a priority Lack of centralized communication strategy to promote oral health Lack of or limited oral health budget at the state level |

Oral health education interventions conducted by primary care workers |

| Policy characteristics |

Lack of awareness of national policies and oral health guidelines Poor integration of oral health services Lack of community engagement to address oral health Lack of strategic planning |

Increased awareness of non-communicable diseases |

| Policymaker characteristics | Poor integration of oral health services | |

| Research and researcher characteristics |

Limited access to research evidence and local information Lack of qualified research personnel |

|

| Consumer/patient-related characteristics |

Limited sources of oral health information to parents/caregivers and patients Limited oral health education Oral health diseases not a priority |

Increased awareness of consumers/patients about dental health care services Mass media sensitization to health-related topics |

- * Themes adapted from Oliver and colleagues.18

3.4 Barriers to and facilitators for the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of OHPs

Seventy-four reports informing barriers to and facilitators for implementing, monitoring, and evaluating OHPs, which are the most studied policy areas (Figure 2, and Table S2), were identified. Organization and resources continue to be the most reported theme across included studies. Identified barriers included the lack of workforce coordination among stakeholders, financial constraints affording and accessing oral health care, financial constraints implementing and sustaining oral health programs, and the irregular supply of consumables, medicines, dental materials, power and water. Identified facilitators for implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of OHPs included increased interest in developing public oral health programs, the increased number of dental schools adopting community-based training for dental students, the willingness of elementary and secondary schools to partner with other stakeholders for oral health promotion, and the increased access to information technologies and telemedicine (Table 3).

| Themes* | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Contact and collaboration |

Poor integration of oral health services Stakeholders' resistance and scepticism Lack of mentorship programs and interdisciplinary professional education Breakdown in communication between providers and national authorities Stakeholders mismatch in regulation and accreditation Insufficient digital infrastructure for data sharing Insufficient adherence to and use of clinical practice guidelines |

Creation of national oral health policies is an increased priority Increased interest in developing public oral health programs Support from the World Dental Federation (FDI) conducting oral health awareness programs nationally Increased private-public sector coordination to provide better access to oral health care services Partnership with traditional healers to increase their oral health knowledge Increased provision of oral health education by non-dental professionals Initiatives to increase referrals from nurses to dental facilities Willingness of primary and secondary schools to partner with other stakeholders for oral health promotion Increased awareness of the impact of social determinants of health among oral health care providers |

| Organization and resources |

Long distance to oral healthcare clinic or school-based program Poor integration of oral health services Focus on therapeutic as opposed to preventive interventions Lack of training and consideration of non-dental professionals Stakeholders' lack of workforce coordination Lack of or limited oral health budget at the state level Oral health diseases not a priority Poor organizational structure of ministry of health Lack of information on dental visits Shortage of educational material Limited availability of healthcare services and infrastructure Financial constraints to afford oral health care Financial constraints to access oral healthcare Absence of a monitory body to regulate oral healthcare professionals Insufficient workforce to provide oral healthcare services Lack of efficacy and training of oral health professionals Irregular power and water supply Salaries in public sector not competitive Low morale among healthcare professionals and researchers Governance instability Lack of robust health information systems Financial constraints to implement and sustain oral health programs Lack of oral health services at the public sector level Irregular supply of consumables, medicines, and dental materials |

Increased capability to train health care professionals including dentists and dental assistants |

| Growing interest in improving oral health care access | ||

| Increased interest in training middle-level oral health professionals | ||

| Some governments prioritizing the expansion of funding and fiscal space for oral health | ||

| Some dental schools have adopted a community-based training for dental students | ||

| Increased access to information technologies and telemedicine | ||

| Policy characteristics |

Lack of or inefficiencies in planning and managing oral health services Lack of awareness of national policies and oral health guidelines Lack of national oral health policies and guidelines Policies and guidelines lacking implementation plan Poor integration of oral health services Lack of community engagement to address oral health Lack of strategic planning |

International movement towards oral health policies and evidence-based practices Increased interest in developing public oral health programs Efforts to improve monitoring and evaluation of national policies to increase accountability and learning Creation of national oral health policies is an increased priority Increased awareness of non-communicable diseases |

| Policymaker characteristics |

Stakeholders' resistance and scepticism Lack of or inefficiencies in planning and managing oral health services Poor integration of oral health services |

|

| Research and researcher characteristics |

Limited access to research evidence and local information Lack of qualified research personnel |

Efforts to improve monitoring and evaluation of national policies to increase accountability and learning Some governments started promoting the conduct of oral health research locally |

| Consumer/patient-related characteristics |

Focus on therapeutic as opposed to preventive interventions Oral health diseases not a priority Limited oral health education Limited sources of oral health information to parents/caregivers |

Growing awareness among secondary school children of the value of oral health prevention |

|

and patients Cultural perception of illness Oral hygiene implements not available in the market |

- * Themes adapted from Oliver and colleagues.18

4 DISCUSSION

This scoping review aimed to determine barriers to and facilitators for creating, disseminating, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating OHPs in the WHO African region reported in research articles and health policy documents published between January 2002 and March 2024. The majority of member states in the region lack a country-specific body of evidence to assist policymakers in anticipating barriers to and facilitators for oral health policy initiatives. Most of the research articles and documents reported on barriers to and facilitators for the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of OHPs; organization and resource issues were among the most frequently mentioned barriers.

The most common type of barrier identified focused on the theme of organization and resources for all OHP stages. On the other hand, the contact and collaboration theme was the most common type of facilitator reported for the creation, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of OHPs. Across policy stages, some of the most commonly reported challenges that stakeholders face included financial constraints, limited and poorly planned workforce, lack of prioritization of oral health, lack of health information systems, poor integration of oral health services with the health system, and limited oral health education and literacy. The most commonly cited facilitators across all policy stages included an increased priority for the creation of national OHPs, an increased awareness of the need for a diverse and inclusive stakeholder engagement in policy initiatives, an increased relevance of NCDs, a diversification of the oral health workforce, and an increased awareness of the impact of social determinants of health among oral health care providers.

Governments, policymakers, professional and patient partner organizations, and healthcare administrators in the WHO African region should initiate a country-specific multi-stakeholder dialogue regarding the pertinence and extent of the barriers and facilitators identified in this review. Such a stakeholder dialogue would require an assessment of which barriers should be addressed first and in what order (identification and prioritization exercise), what the expected synergies across the policy stages are when a specific barrier is targeted (expected net benefit), the impact of addressing a particular barrier (assessment of success), and how identified facilitators play a role across the policy stages. The reported barriers and facilitators identified in this review are inextricably connected; that is, it may not be possible to tackle one barrier until another upstream barrier is addressed first. A diverse group of stakeholders – government agencies, policymakers, staff and members of civil society groups, healthcare administrators, health care providers, insurers, researchers in governmental organizations, the private sector, and academia – should interact in a structured, collaborative, common ground-oriented, evidence-informed dialogue to identify barriers and facilitators for the production and enactment of OHPs using a subnational and national scope.19, 20 This review found no documents focusing on researchers' perspectives regarding barriers to and facilitators for OHPs in the WHO African region.

The WHO has published an action plan to translate the global strategy for tackling oral diseases.5, 21 Academic institutions and other research-oriented public and private organizations are integral in achieving the targets of the WHO action plan. Such institutions and organizations can partner with stakeholders across sectors to create necessary local evidence to inform OHPs, assess their population-level impact, and evaluate necessary modifications in their implementation. National-level partnerships between investigators and stakeholders represent an opportunity to optimize research conduct, minimize waste, and facilitate the translation of research findings to policy decision-making. To move OHPs to the next level, African-led, financially supported, culturally conscious research conducted at African universities as part of larger multi-national consortiums (south–south collaborations) and published in journals that are accessible to policymakers is needed.22, 23 These efforts should go beyond academia, including the use of robust epidemiological models and health information systems to assist in evidence-informed oral health policies at all stages.24, 25

The novelty and timing of this review are among its strengths, given the current efforts of member states and WHO to improve OHPs in the African region.26 Another strength is the creation of a comprehensive multi-database and multi-discipline search strategy by two information specialists with expertise in systematic search in both the health and social science fields. This search strategy was peer-reviewed by a third information specialist not directly involved in the project. Another strength of this work is the rigour of the document selection and data extraction process, conducted independently and in duplicate. This is the first review systematically identifying barriers to and facilitators for OHPs in the WHO African region. This review also has limitations. Most evidence comes from articles produced in Nigeria and South Africa that used a national scope and, as most documents in this review, were limited to barriers to and facilitators for OHP implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. In addition, the content analysis, although helpful in identifying themes suggesting barriers and facilitators, does not provide an in-depth analysis of the impact of each barrier and facilitator nor address the importance that stakeholders at a country level would assign to those issues.

Investigators interested in assessing barriers to and facilitators for OHPs using systematic methods should prioritize a data-driven approach using a multi-stakeholder perspective that identifies issues and provides insights to overcome barriers and maximize the desirable effect of existing facilitators. In addition, assessing country-specific policy capacity, that is, ‘… the set of skills and resources—or competencies and capabilities—necessary to perform policy functions’.27 can facilitate a deeper understanding of the analytical, operational, and political skills and competencies within and across member states. Such assessment can further explore policy capabilities at individual, organizational, and systemic levels from the perspective of a variety of key players, including government agencies, political parties, non-governmental and international organizations, and the private sector. The capacities of these entities significantly influence the overall government's ability to execute its policies.27 Our review did not identify any existing document using the framework presented above to assess policy capacity in the WHO African region.

5 CONCLUSION

The effective creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of OHPs in the WHO African region face significant challenges and opportunities. The main obstacles identified include financial constraints, a limited and poorly planned workforce, low prioritization of oral health, inadequate health information systems, poor integration of oral health with general health services, and limited oral health education and literacy. On the other hand, factors that can enhance OHPs include increasing awareness of the importance of prioritizing national oral health policies, involving a wide range of stakeholders, recognizing the significance of non-communicable diseases, diversifying the oral health workforce and understanding the impact of social determinants on oral health. These findings underscore the need to initiate country-specific multi-stakeholder dialogues to prioritize and address barriers while leveraging facilitators strategically. Academic institutions and research organizations should collaborate with various stakeholders, including Ministries of Health, to generate local evidence, assess the population-level impacts of OHPs and assist in their practical implementation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FVP, OU, CNMZ (African researcher), IVK, MG, and ACL created the study protocol. EB and HAB created, executed, and documented the search strategy. FVP, OU, MG, and ACL designed screening and data extraction forms. FVP, OU, CNMZ (African researcher), CCMP, HA, JB, CPG, JV, and ACL screened references for eligibility. When needed, OU and ACL served as judges for defining final eligibility. CCMP assisted with screening and data extraction of articles in Portuguese. JB assisted with screening and data extraction of articles in French. FVP, OU, CM, HA, JB, CPG, JV, and ACL conducted data extraction. FVP, OU, MG, and ACL analysed data and designed tables and figures. All authors approved the final draft of this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to the University of Pennsylvania, School of Dental Medicine Library Director, Ms. Laurel Graham, and staff, who assisted with retrieving full-text documents, and to Dr. Yuka Makino, Noncommunicable Diseases management team, WHO Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Congo, for her technical input and assistance in determining the scope of this review.

Francisca Verdugo-Paiva is a PhD candidate at the Doctorate Program on Biomedical Research and Public Health, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors have not declared a specific grant from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agency to support this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare having no competing interests.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

This scoping review did not collect individual participant data. Patient consent is not applicable.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

All materials in the tables and figures presented in this work are original.

STUDY REGISTRATION

The protocol of this scoping review can be found in Carrasco-Labra A, Verdugo-Paiva F, Matanhire-Zihanzu CN, Booth E, Kohler IV, Urquhart O, Makino Y, Glick M. Barriers to and facilitators for the creation, dissemination, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of oral health policies in the WHO Africa region: A scoping review protocol. F1000Res. 2024 Mar 15;12:1160.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All relevant data from the study are included in the figures and tables in the manuscript and supplementary material.