In remembrance of Victor Rico Gray (1951-2021): An astonishing tropical ecologist

Abstract

In this remembrance, we have brought together some of Victor Rico-Gray’s friends and collaborators to recall his many contributions to tropical ecology and his influence on so many young scientists. Victor’s research ranged from Mexican ethnobotany to the evolutionary ecology of complex interactions between ants and plants. His research was highly collaborative, forming strong bonds among those who shared his interests in how the web of life is organized. He inspired students through his mentoring in tropical ecology, mainly his lectures at the Instituto de Ecología AC (INECOL), and later at the Universidad Veracruzana (UV), his courses organized by the Organization for Tropical Studies (OTS), and his talks at meetings, including the Association of Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC). Victor’s story is not over. It will continue to be traced through countless scientists who were inspired by Victor’s life and work.

1 INTRODUCTION

The life story of the great Mexican ecologist Victor Rico Gray is fascinating. He was born in Mexico City on June 11, 1951, son of the Doctor Carmelo Rico Belestá (1899-Spain) and the nurse and captain of the army Thomasina Gray Wikilson (1913-Scotland) (Figure 1a). Perhaps the spirit of warrior and love for justice were inherited from his parents who each participated in different wars: his father in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and his mother in World War II as captain of a battery of anti-aircraft guns in the defense of Liverpool, England. His parents married in Mexico City in 1949. Shortly after Víctor (1951) and his sister Carlota were born, the family moved to Ciudad Valles, in the state of San Luis Potosí in northeastern Mexico. After a childhood full of natural landscapes and love of his family, Victor traveled to Mexico City to study at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM, Mexico) and received a biology degree in 1979. As an undergraduate, he measured the productivity of a mangrove off the coast of the state of Veracruz, Mexico, under the supervision of Dr. Antonio Lot. His teaching spirit had already been awakened: When he was still undergraduate, Victor was already an assistant to a professor in Ecology courses.

Shortly after receiving the title of biologist, Victor started working as a research assistant in the Flora of Veracruz project of the National Institute for Research on Biotic Resources (INIREB) where he remained in that position until May 1980. He then moved to the Center for Biotic Resources of the Yucatán Peninsula (also part of the INIREB) to become the curator of the herbarium and a researcher at that institution. Between the 1980 and 1982, Victor also participated in some editions of the population ecology course organized by the Organization for Tropical Studies (OTS) and the University of Costa Rica where his passion for tropical ecology and conservation was beginning to awaken more widely. During that period, Victor pioneered primatological studies in southern Mexico, with a strong academic collaboration with Dr. Elizabeth Watts (Tulane University).

Motivated to continue studying tropical ecology, Victor moved to New Orleans to study with Dr. Leonard B. Thien, driving to New Orleans from Mexico. On the way, his car exploded, burning up his possessions, so he arrived penniless! Leonard arranged for him to stay in a friend’s garage in exchange for helping around the house. Victor completed his master’s degree (1984) and his PhD. (1987) and continued collaborations with Dr. Leonard B. Thien for some years, studying Beaucarnea (Asparagaceae) and other unique plants of Mexico. Going to New Orleans was ideal for Victor, as he was passionate about jazz music and that passion would accompany him throughout his life. During his graduate studies, Victor studied the effect of myrmecophily on the reproductive fitness of Schomburgkia tibicinis (Orchidaceae) in the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. After finishing his PhD, Victor returned to Veracruz to dedicate all of his time to working at INIREB. But soon after (1989), he moved to Mexico City to take up a research position at the Center of Ecology at UNAM where he remained until 1991. In that same year, Victor was hired by the Instituto de Ecología AC (INECOL) in the city of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. At INECOL, Victor was able to develop his full potential as a researcher and professor of tropical ecology and conservation, coordinating the postgraduate field course in ecology at that same institute for several years. As coordinator of INECOL’s graduate program, each Friday he organized a get-together with students and researchers, always with music, where sometimes he performed with his jazz band, playing the drums. Beside jazz, Victor loved reggae music (visiting Jamaica sometimes) and he was one of the biggest fans of the Rolling Stones. He attended their concerts around the world, purchasing their CDs, and adding to his growing collection of memorabilia (more than 150 different t-shirts, books, and many more). In his home in the city of Coatepec (Mexico), he had a special room to listen music and enjoy music videos from all of his admired musicians, and of course to play his drums.

After two decades dedicated to research and teaching at INECOL, Victor assumed a researcher position at Universidad Veracruzana (UV) in 2010, also in the city of Xalapa, where he remained actively working with plant–animal interactions until the last moments of his life. His important and productive academic trajectory has earned him numerous awards, including being chosen as a Corresponding Member of the Botanical Society of America (2019), several Awards in Tropical Botany (from the Garden Club of America), George Henry Penn Memorial Award (Tulane University), Serfin National Award: The Environment (Mexico), and the title of Honorary Researcher at University of Alicante (Spain). Victor was also a member of The New York Academy of Science (USA), Mexican Academy of Sciences (Mexico), Botanical Society of Mexico (Mexico), Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation, and the Mexican National System of Researchers (Mexico).

2 IMPACT ON TROPICAL ECOLOGY AND TRAINING NEW SCIENTISTs

Like most outstanding scientists, Victor’s academic trajectory was shaped over time. His works were and continue to be of great impact in numerous areas of tropical ecology, including plant reproductive biology, primatology, ethnobiology, among others, but his greatest highlights were the studies involving the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of plant–animal interactions. He collaborated with his wife Monica Palacios Rios and Suzanne Koptur on studies of nectaries in ferns, discovering that the nectaries function to attract ants that discourage herbivores (Figure 1b).

I (Wesley) remember that one day I asked Victor what his area of research was, and he replied: “I am a trained tropical botanist, but I have a great interest in any organism that interacts with a plant” (Figure 1c). His seminal studies on the ways in which species interact in nature are known worldwide. Victor was also one of the pioneers to study the interactions between ants and plants in tropical environments. I (Wesley) had the pleasure to see his field notebooks and was impressed by the amount of information and details about natural history of species interactions from many different regions.

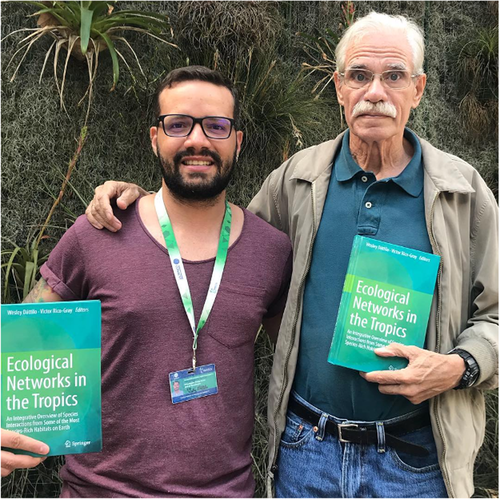

This passion for ant–plant interactions brought Victor together with his great friend and collaborator Paulo S. Oliveira from the State University of Campinas (Unicamp, Brazil). The result of this great meeting was the book The Ecology and Evolution of Ant-Plant Interactions published in 2007 by the University of Chicago Press. This book had a major impact in the field due to the high quality of details and wealth of knowledge that was compiled. Victor has always been passionate about ecological interactions and its role in the structure and stability of biological communities. In his conversations with his friend John N. Thompson (University of California, USA), he started to see the relationships between species in a more integrative way. At that moment, John told Victor that some ecologists were beginning to use tools derived from complex network theory to describe ecological interactions. Victor was extremely interested in the topic and together with John N. Thompson, Paulo Guimarães Jr (University of São Paulo, Brazil), and Sérgio Furtado dos Reis (Unicamp, Brazil) published the first paper on ant–plant mutualistic networks. This theme was one of his main academic passions at the end of his career. Victor was thrilled to talk about the complexity of ecological interactions and mentored two PhD students in their projects involving ant–plant interaction networks, the Mexican Cecilia Díaz-Castelazo (in 2005) and the Brazilian Wesley Dáttilo (in 2015). These two alumni still follow in the footsteps of their mentor and continue to the present day with this line of research. Victor’s last great work was the book Ecological Networks in the Tropics: An Integrative Overview of Species Interactions from Some of the Most Species-Rich Habitats on Earth published in 2018 by Springer edited together with Wesley Dáttilo (Figure 2). This book has a forward by John N. Thompson and includes chapters authored by scientists from around the world, most of them Victor’s friends.

Apart from all the academic importance of Victor’s works, one of his main characteristics was the pleasure he felt in transmitting his knowledge. Victor has always been involved with graduate studies and the interaction with students at all the institutions he has visited. Many times, he went and paid for tickets to enjoy Rolling Stones concerts in Mexico and other countries with his students (e.g., Juan Serio-Silva), or having a good and funny talk with us visiting restaurants with the best burgers, tacos or hot cakes in the town (he loved such food!). Victor emphasized the importance of scientific collaboration for the progress of science, and he always told us: "we need to assemble a team to answer this research question". His simple and calm way of talking captivated and connected people.

Victor was always very attentive to all the people who approached him. The doors to his office were always open to anyone who wanted to talk about any topic: from his trips to the reggae festivals in Jamaica to the most expressive article on ecology published that week. The great accumulated knowledge about tropical ecology and conservation was always shared in the innumerable graduate courses he gave at different universities around the world, including the classic courses in tropical ecology organized by OTS. Over the course of his career, Victor trained and transformed the lives of more than 40 people including undergraduate and graduate students, and many of them continue to do science (and of course enjoying music) and take Victor’s teachings to different regions of the world.

3 GOOD MEMORIES AND ANECDOTES

Victor completely changed my life and that of my family. He invited me to do my PhD studies in Mexico under his supervision without knowing me, he held out his hand to me when I needed it most. I spoke neither English nor Spanish on the first day he received me at his office, and I still remember Victor trying to speak Portuguese to calm me down and make me feel comfortable. I still keep a T-shirt that he gave me the first time he went to Jamaica at a Reggae festival. Victor connected me within his network of friends and collaborators. Victor showed me the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and that doing science with friends is more fun and enjoyable. Victor's story is not over, it will continue to be traced through countless scientists who were and will still be inspired and motivated by Victor's life and work. Always on our minds, forever in our hearts “Maestro”. (Wesley Dáttilo)

Victor was more than my professor, almost an adoptive father who gave me his hand and his guidance during my master and PhD degrees. I had been conditioned in my previous job, that if I made the decision to do the PhD at INECOL, I had to give up nine years of job, when I already had a family with my wife and son. Really after having Victor's help and starting to interact with him everything changed and doing science made sense. Living with Victor, with his cats that he loved so much, being at his home many times, with his family, learning about his musical tastes, making jokes about everything and everyone (although he always looked very serious) taught me that the world was a lot bigger and that I had a commitment to science following in the footsteps of a world ecology leader such my dear “Doc. Victor". I will really miss Victor and he leaves a void in my soul that I hope to fill by honoring his steps and trajectory. (Juan Carlos Serio-Silva)

Victor’s dedication to family, friends, students, his scientific work, and his many personal interests was evident in everything he did. Among the flood of personal memories that come to mind are these:

- days at La Mancha field station near Veracruz, watching Victor build the students’ interest in the diversity of life;

- our travels in Brazil to give talks in Uberlandia and Mato Grosso do Sul and then to explore part of the southern Pantanal with Erich Fischer and his students;

- our travels in the Yucatan many years ago, with Victor Parra, two of Victor P’s students, and my wife Jill, as we searched for study sites, listened to Victor RG talk about the ethnobotany of the region, visited Mayan temples, and — as always with Victor RG — stopping at good restaurants;

- Victor’s insistence that, prior to publication, he go over every page of an upcoming Spanish translation of one of my books on coevolution to make certain that the professional translator for the book had retained the nuances of each paragraph and sentence;

- Victor’s patience as he corrected my written Spanish on my rare attempts to write a simple email to him in Spanish;

- traveling with him in Washington State to find, successfully, a particular brand, style, and size of cymbal that Victor could not find in Mexico;

- learning from Victor about jazz music, who took his role as my jazz appreciation instructor seriously;

Victor gave much, time and again, to those of us fortunate to have him as a friend. (John N. Thompson)

Victor visited us in 2005, for ten days he cheered our environment with his stories, comments, and great advice. We visited the Brazilian savanna and had good times in the field as in a table among friends and my family. That was the time of the ATBC in Uberlândia. I will never forget our fun dinner with Bob Marquis, Rodolfo Dirzo, Helena Maura Torezan-Silingardi, Peter Price , John and Jill Thompson and my three sons (Figure 3a); a memorable night like it was Victor's talk on ATBC. After that, Victor, John and Jill visited the Pantanal, an old dream of Victor. Our friend never shied away from helping us with scientific texts, discussing works, ideas and participating in collaborations. He was an enormous collaborator of the Brazilian ecology community and an unforgettable friend. (Kleber Del Claro)

Looking back I realized how lucky I was to explore the structure of mutualistic networks with Victor at dawn of the field and at my infancy as a researcher (Figure 3b). As a student, Victor’s work with Paulinho Oliveira shaped an entire generation of ecologists in Campinas that fell in love with ant-plant interactions. Later, as a friend and collaborator, I learned a lot from him about ecology, evolution, natural history, and ecological interactions. And about music, pop culture, food, and Mexico. Victor contributed to imprint on me the view that science is a truly international enterprise and that it is best done among friends in non-formal environments. When I found out about his passing, I recollected that a few days before I was showing to my daughters, Alice and Marina, some Crematogaster ants visiting the post-floral nectaries of a tiny plant (Richardia brasiliensis, Rubiaceae) in the garden. My daughters were dazzled with the awe of ant-plant interactions that Victor helped to elucidate. I think Victor would enjoy this story. (Paulo R. Guimarães Jr)

Victor and I first met at the Symposium on Ant-Plant Interactions (organized by Camilla R. Huxley and David F. Cutler), held in Oxford University in 1989. We would meet again at the 1995 Annual Meeting of the Association of Tropical Biology and Conservation (San Diego, CA), when we decided to establish a collaboration on our common research interests. During 1997 and 1998, we carried out a series of field observations and experiments on ant-plant-herbivore interactions in the sand dunes of Veracruz, at La Mancha Biological Station, on the coast of the Gulf of México. We developed a strong friendship and scientific partnership. Our collaboration grew stronger over the years, and culminated in our 2007 Ant-Plant book. I learned a lot from Victor’s wide knowledge of natural history, and of the past and present Mexican culture. Tropical biology and Mexican science lose a master. All I have from my great friend Victor is good memories, gratitude, affection, and admiration. (Paulo S. Oliveira)

I could say Victor took my hand when, in my first travel to Costa Rica in 1980, I saw the tropics for the first time. Together with Gary Stiles I was collaborating with the OTS courses for several years and I met Victor in one of the courses, thus sharing a parallel encounter with the rainforest. Since that time we kept a good friendship, revitalized in recent years with several collaborations. I recall from Victor his encyclopedic knowledge of tropical ecology, from ants to primates to orchids to plants (any plant) and broader aspects of community ecology, biogeography and, very specially, coevolution. Besides all this I delighted his conversations on music, and his deep knowledge of jazz music in Spain, with most interesting discussions about analogies between jazz and flamenco. His friendship is a jewel, one of those that help you find your way because he was a reference not just for students, also for colleagues like me, privileged with crossing our paths with Victor. (Pedro Jordano)

Victor was a unique scientist and person extraordinaire, quiet and respectful on the outside, but passionate on the inside about his science, his love for music, and his family. He was one who literally could and would reach across international borders, bringing scientists together to interact and to share his passions. I recall his plenary address at the 2005 ATBC annual meeting in Uberlândia, Brazil, in which he gave a fiery plea, addressed in particular to young students: read the “old” literature, converse with the giants of ecology while they still are available, and value the lessons of natural history. In essence, his message was that all of our understanding of tropical biology is based in natural history; we must not abandon that discipline, if we are ever to have a chance to conserve this biome that we so much hold dear. I thank you Victor for the opportunity to visit your home with friends in Xalapa, and then for the chance to return that favor upon your visit to St. Louis. I will cherish these memories always. (Robert J. Marquis)

Victor mentored many students, both men and women, at undergraduate and graduate levels, from many institutions. He was especially supportive of under-represented minority students, and was a true STEMinist, feeling that equal representation is desirable in academia as it is in other areas of life. Dr. Victor Rico-Gray was a colleague and friend of many years, a stellar scientist, an excellent teacher, and great research mentor. Victor achieved a great deal in our field, as well as in his life outside Biology. His death leaves a large void in both my professional and personal life. I had the opportunity to take two sabbaticals to work with Victor in 1994 and 2009 at INECOL studying ferns with nectaries and their interactions with herbivores and ants (Figure 3c). The kindness and friendship he and his family shared with us made our time in Mexico rich, wonderful, and unforgettable. (Suzanne Koptur)