On Subjectivity and the Relationship with the Other: Qualitative Results of an Interview-Study with 50 Young Muslims

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the relationship between subjectivity and the other during the course of integration among 50 young Muslims of dual national heritage in Germany. The largest group of migrants within Germany are people of Turkish and Kurdish origin. During the summer and autumn of 2018, we interviewed 50 individuals of both genders aged between 18 and 25. The interviews were carried out and evaluated in North Germany. We saw that the ‘feeling of being held’, ‘being-able-to-process-(negative)-experiences’ and ‘to take responsibility for oneself and other’ are characteristics of well-educated young Muslims. Those who feel at home in their Turkish family or in the Islamic religion are able to process positive and negative experiences and present more (mature) super-ego structures. This allows them to be able to deal with the challenges of migration and integration. Based on the data, we developed the ‘Triadic Model of Integration’ within the Lacanian L-Scheme of Subjectivity.

INTRODUCTION

I still find it extremely outrageous how other (German) people around me have taken the liberty to tell me who or what I am, where my roots lie and where I belong. Ultimately, such experiences have led me to distance myself more and more from the ‘I-am-German part’. A few years ago, I would have said I am German-Turkish. Today I would rather say I am Turkish-German. So, I would put Turkish before German, because I don't experience in Turkey what I have experienced here.

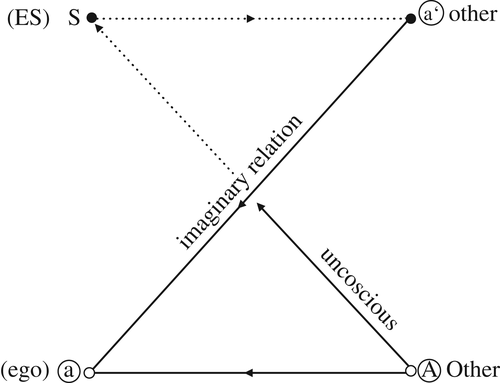

This quote demonstrates the dynamic between the subject and the other, showing how the participant has to find her way to personal identity. To examine these processes, we refer to Lacan's scheme L. In this scheme, we find a strong connection between the big Other and the subject of the unconscious, that is, the part of the subject being unconscious (Lacan, 1991a, pp. 142 − 3, 1991b, p. 243; Evans, 2006, pp. 173, 198). Figure 1 shows Lacan's L-Scheme.

The message, our message, in all cases comes from the Other by which I understand ‘from the place of the other’. It is certainly not the common other, the other with a lower-case o (in French: a, autre, P.K.) and this is why I have given a capital O (in French: A, Autre, P.K.) as the initial letter to the Other of whom I am now speaking (Lacan, 2015, p. 45).

This momentous split is the product of the functioning of language … Though the subject is nothing here but a split between two forms of otherness − the ego as other and the unconscious as the Other's discourse − the split itself stands in excess of the Other (Fink, 2017, p. 45).

In our example, the German acquaintances took the place of the big Other by determining the participant's subjectivity: they claimed to know her roots and who she was. In the unconscious, the Germans become the big other who linguistically determines the identity of the Turkish participant. In order to evade this powerful determining influence, the participant fled back to the primordial determination, that is, being primarily Turkish.1

The second vector (in the L-scheme) is the imaginary connection between the ego (a) and its mirror image (a’). The ego (a) recognizes itself in the others (a’), like in a mirror, and the others seem to be nothing more than imaginary copies of the ego. In his early writings, Lacan understood ‘structure’ to be ‘external social structures’, for example, the emotional relationships between family members (Evans, 2006, p. 195). In assuming that these social relations become internalized, Lacan shuffled his formerly superficial view: ‘Structure’ includes now both the intersubjective and intrasubjective dimensions: The big Other (A) is now understood intersubjectively (as family, religious or social institutions) as well as intrasubjectively (as the ego-ideal, i.e. the superego). The ‘structure’ is also doubled on the second, imaginary axis: The imaginary intersubjectivity of our participants may be shown by the fact that almost all of them chose a partner from their own cultural background. Moreover, the imaginary intrasubjective structure is reflected in the participants’ ideal ego that requires a high degree of professional performance and social success. These ideas refer exactly to the questions concerning the relationship between subject and structure in the context of migration. In our example, the young lady represents the subject. The structure (or system) is represented by the other people, the acquaintances, who give her the feeling of being a second-class citizen. The dialectical relationship between subject and structure shows itself in the non-recognition and the participant's withdrawal of accepting the German identity. This libidinous de-cathexis can be understood as a typical answer to the social non-recognition as autonomous individual.

As the literature suggests, Islamic migrants experience profound processes of cultural or political transformation. An important and widely acknowledged psychoanalytic work on migration comes from León and Rebeca Grinberg (2009). In this work, the authors primarily deal with the conscious and unconscious effects of migration on identity, that is, how the migrant's subjectivity is established. They provide a compact overview of the broad spectrum of various disorders that can occur as a consequence of migration. Migration may trigger different types of anxieties: separation anxiety, persecutory anxieties arising from confrontation with the new and unknown, and depressive anxieties affecting the loss of the former world. Migration is therefore associated with fear of separation, loss and abandonment (Schaich, 2012, p. 522). In Lacanian terms, the split subject is confronted in a more or less frightening way with a newly emerging big Other (A) as well as with the loss of the familiar imaginary other (a’). It could be that after the attacks of 9/11, the hostility of the Western societies made this confrontation even tougher. Above all, migrants from the Islamic world currently experience profound processes of political, cultural and social transformation in their countries (Benslama, 2017). In this respect, the big Other, represented by the Islamic-Turkish culture, may be in a state of critical upheaval being characterized by conflicts between progressive and conservative forces. Morel (2018) describes how the Islamic subject radicalizes in extreme cases. Radicalization could be seen as a revenge against a society that is viewed as unjust. It is the answer to extremely painful non-recognition. From this point of view, radicalization could be discerned as a possible outcome of a predominantly failed integration.

In this context, this study aimed to examine the relationship between the subject and various aspects of the structure in the integration of young Muslims in Germany. We understand structure and system as synonymous representations of the other (including the big Other). On the basis of our results, we will conceptualize the idea of integration in terms of Lacan's subject theory. Our main questions revolved around the topics: What attitudes and feelings do young Muslims express in connection with their socio-cultural integration in German society? Which tendencies towards objectalization and disobjectalization can be seen? Are there any gender-specific differences? The results on (dis)objectalization and gender specificity will be published in a different paper.

How We Designed Our Study

We conducted a total of 50 qualitative research interviews with Turkish and Kurdish Muslims between 18 and 25 years of age. This study was approved by the ethics board of the University of Lubeck (10 October 2017). The study was conducted at the Hospital of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Bad Segeberg and the University-Ambulance of the Medical School Hamburg (MSH). The study spanned three years. Preparations began in 2017. We collected data from June 2018 to November 2019. Data analysis began during data collection. We planned to examine a sample with the broadest possible social stratification. This is why we reached out to Islamic communities, associations and advice centres in Hamburg and the surrounding cities. Also, we hung up notices about the study at the MSH. We however encountered considerable reluctance with our research project in Islamic institutions. Only the members of a single Islamic community association agreed to be interviewed by us. The majority of our participants are students who were very willing and open to participate in the study. So, on the one hand we encountered a strong reluctance, whilst on the other hand, several participants emphasized how important it was for them to make their voice heard. We suspected that the topic of integration or disintegration is currently regarded as highly problematic, so much that prospective participants did not want to get involved in an audio-documented interview study.

In order to achieve theoretical saturation, that is, to record the total variance of a phenomenon, 20 to 40 interviews are recommended (Glinka, 1998, quoted from Küsters, 2009). With our approach of conducting 50 interviews, we sought to ensure that as many possible phenomena could be included. The Muslims who took part in the study (N = 50) were aged 18 − 25 years (M = 22.32, SD = 1.93). Female and male participants did not differ in terms of their age (U = 305.50, Z = −0.14, p = 0.89). Three participants were about to finish high school (6%), three were vocational school students (6%), seven were employed (14%) and 37 were university students (74%). We would like to emphasize that the reports of this study are to be understood as statements about a group of well-integrated young Muslims of various denominations of Islam.

The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide. The questions included the following areas: relationship experiences, self-awareness/self-image, conflicts and traumatic experiences, physical experiences, gender identity and migration. The interview style was an open conversation. We invited the participants to talk freely about themselves and their world, creating a safe space for them to make associations and develop spontaneous narratives. With the participants’ written consent, the interviews were audio-documented, transcribed and imported into computer software. The transcription generated 1204 A4 pages. The content of the interviews was analysed using the qualitative software program atlas.ti.

METHODOLOGY OF OUR PSYCHOANALYTICALLY ORIENTED RESEARCH

We initially carried out a test coding of the first 10 interviews. Based on this coding, we created a codebook that served as the basis for coding of all interviews. Therefore, elements of the qualitative content analysis, which contains the deductive/structural codes, were linked with the inductive/open approach of grounded theory. Structural and open codes were designed, and ideas and observations recorded in memos during the analysis process.

The structural codes (SCs) were derived from Lacanian theory. We established these before the coding of the interviews. They include the subject and the relationship between subject and structure. There are several definitions in psychodynamic literature describing what a subject is. Freud (1915, 1920) understands it to be the psychological reality of a person. Lacan (1993) regards the subject as the precipitate of the big Other and speaks of the subject of the unconscious (Žižek, 2001, 2008). In our study, the term subject initially refers to the interviewed person who reports about himself/herself and his/her world (including the possibility that the unconscious is determined by the big Other). Furthermore, the subject is always in a constitutive reciprocal relationship to the structure (Lacan, 2015; Mura, 2014; Recalcati, 2000): The structure helps the subject to create a linguistic, social, political and cultural order (Greshoff & Schimank, 2006; Srubar, 2005). The forms (SCs) of the relationship between subject and structure used for this work are subject-family, subject-culture Germany, subject-culture Turkey, subject-religion Christian, subject-religion Islamic, subject-social Germany, subject-social Turkey, subject-institutional Germany and subject-institutional Turkey.

During the data analysis of the first 10 interviews, we also developed open codes (OCs) that were directly related to the participants’ statements. We then designed a codebook for the structural and open codes with a definition and anchor examples. The following 40 interviews were coded with the help of this codebook. In memo writings, all ideas, associations and mini-theories are recorded in the form of memos during the coding process (Glaser & Holton, 2004). This is where the actual grounded theory process takes place, which also allows the connection to a psychoanalytically oriented approach.

The methodological approach of the grounded theory methodology is based on the premise ‘all is data’ (Glaser, 2001). According to this premise, any data material can be checked and used within the framework of the research process (Glaser, 2007). The grounded theory methodology (GTM) according to Glaser and Holton (2004) is not a theory in the conventional sense. Rather, the GTM provides the basis for discovering, working out and generating hidden theories from diverse data (Glaser & Holton, 2004; Mey & Mruck, 2011, 2014).

For the present research, the Glaser approach plays an important role, especially with regard to open coding and notation. Emerging ideas, associations, hypotheses and theories were recorded during the coding process in the form of memos. The participants’ verbal statements were linked with inductive codes (OCs) in accordance with the grounded theory methodology in the sense of open coding. In the final steps of the analysis, the simultaneous occurrence of structural and open codes (‘co-occurrence’) was examined. Furthermore, the interrater agreement was determined for the structural and open codes used. According to Mayring (2015), intersubjective agreement is an important prerequisite for qualitative research. This correspondence between two raters was calculated using the statistical measure Cohen's kappa (κ). In the present study, all codes display good to excellent (M = 0.72; SD = 0.11) interrater agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

RESULTS: WHAT HAVE WE IDENTIFIED TO BE IMPORTANT FOR SUCCESSFUL INTEGRATION?

For the presentation of the results, we selected the three open codes (OCs) which most frequently occur together with the structural codes of subject and relationship between subject and structure.

The open codes are: ‘taking-responsibility’, ‘feeling-held’ and ‘being-able-to-process-experiences’. This triad occurred most frequently both in the subject and in the relationship between subject and structure. In the following, we first describe the co-occurrence of the three open codes both with the structural code ‘subject’ and with the structural code ‘relationship between subject and structure’ in their facets mentioned above. This selection is based on the extensive text material of the interviews. Table 1 gives an overview of the co-occurrence analysis of deductive/structural codes (SCs) and inductive/open codes (OCs).

| Structural codes | n | OC Sa (%) | OC Eb (%) | OC Vc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | 5377 | 1 | 98.45 | 99.65 |

| Subject-culture | 2466 | 57.54 | 56.50 | 50.71 |

| Subject-culture Germany | 829 | 43.79 | 29.31 | 56.45 |

| Subject-culture Turkish | 1220 | 36.64 | 23.93 | 45.82 |

| Subject-religion Christian | 114 | 27.19 | 28.95 | 55.26 |

| Subject-religion Islamic | 938 | 33.69 | 27.51 | 48.93 |

| Subject-social Germany | 1527 | 44.34 | 34.59 | 56.25 |

| Subject-social Turkish | 636 | 21.70 | 20.13 | 30.50 |

| Subject-institutional Germany | 1266 | 40.05 | 26.74 | 55.69 |

| Subject-institutional Turkish | 445 | 19.78 | 13.48 | 31.91 |

- The values are given in per cent and rounded to second decimal. OC S = feeling-held; OC E = taking-responsibility; OC V = being-able-to-process-experiences.

- a n = 1559

- b n = 122

- c n = 2254.

Open Code: Feeling-held

Subject

Many of the participants spoke about experiences from their childhood; how they felt comfortable, safe and in good hands, being recognized and mirrored by the others. They attributed this to the fact that there was a safe and protective space from which they still benefit today: ‘And I am very grateful that I grew up here, I got a lot of possibilities … be it education. Yes, well I feel very comfortable here’ (participant 44).

Subject-family

The participants often said that they feel secure and acknowledged within their family: ‘the most important thing for me is my family … family is my happiness and simply satisfaction’ (participant 5). This feeling forms an important basis for the young Muslims to be able to safely explore the world outside: ‘You had a livelihood and could always fall back on it’ (participant 39). Participants of families with a difficult social background providing little comfort or protection are more likely to develop psychosomatic symptoms such as ‘vertigo attacks’ (participant 1).

Subject-culture Germany

Many participants reported that they feel very comfortable in Germany due to the structured way of approaching things: ‘What I like is that it is very structured’ (participant 26). They use the German culture as a resource for their professional education and are grateful for the security and reliability this culture provides to them.

Subject-culture Turkey

Turkish culture plays a major role not only in the participant's own family but also in the Turkish communities: ‘And there [in Turkey] I also like the people, how they are, I think that's great too, just my family atmosphere, so I feel very, very comfortable there’ (participant 26). Those who do not feel secure can develop psychosomatic symptoms such as ‘dizziness’ or ‘nausea’ (participant 12).

Subject-religion Christian

The Christian religion is rarely described. It is mostly mentioned in connection with other religions or when religion is addressed in general: ‘Religion plays the most important role for me personally, because my religion personally enabled me to turn things around, because I learned how to behave towards other people, that one should not distinguish believers from non-believers, that the atheist is also part of it, that the Christian is also part of it’ (participant 33). At the same time, it is often criticized that the Germans are not religious: ‘German population is not religious. Many are atheistic or non-denominational. I think that's a shame’ (participant 26).

Subject-religion Islamic

Religion plays a very important role for the vast majority of the young Muslims: ‘Well, I have a pretty good memory. That's how you learn suras, i.e., passages, by heart, and I was able to do that fairly quickly. It also had a great social impact, we went to the mosque when I was eight, nine and ten, and you are in a group with your peers’ (participant 12). Those who feel secure by the structure mostly describe it as a personal resource: ‘The religion that takes me further in life because it gives me motivation, because religion simply gives me the necessary strength’ (participant 21). Therefore, religion functions as a good and nourishing introject: ‘You are never alone, that is also yes. That is a special thing that I also need as a person’ (participant 32).

Subject-social Germany

German sports and leisure facilities play a special role, as it helps to develop a feeling of community: ‘I come from a somewhat smaller area in the city. It is usually the case that your schoolmates were also your teammates from soccer’ (participant 38).

Subject-social Turkey

Here the role of the family and the village community is often described, which has a ‘holding’ function. Thus, the family structures on the one hand overlap with the Turkish social structures on the other hand: ‘Well there [in Turkey] funerals take place in a very quick process. The family very quickly came together. You then had this holding very quickly’ (participant 7). Our participants live between the two countries: ‘There they say to you, you are “the German”, here they say to you, you are “the Turk”’ (participant 38).

Subject-institutional Germany

As already mentioned, the interviewees expressed their approval of the German structure. This also includes the institutional facilities within Germany, which further contribute to this experience of reliability. At the same time, they also fear that should they openly show that they belong to the Islamic religion using a traditional characteristic (e.g., a headscarf), they will be discriminated against in society: ‘I would have liked to have studied teaching, but in the back of my mind I feared that I might not be allowed to work with a headscarf. That's why I decided to study pharmacology’ (participant 48).

Subject-institutional Turkey

The institutions in Turkey are less rigidly organized: ‘Then I had to go to the [Turkish] consulate where the administration and bureaucracy were not on time so stressful. I realized: Wow, I'm German’ (participant 23).

Open Code: Able to Process Experiences

Subject

We coded passages that show the differentiation between the young Muslims in dealing with negative experiences: ‘At school, there were situations where other students used words like “Turk” or “Muslim” to throw insults’ (participant 7). A majority of the participants react to emerging challenges with humour, quick-wittedness and tireless energy. Participant 1 described the following incident in which she learned to deal with such situations: ‘Saying things like, when my mother called school, “Wow, your mom speaks German well”, I learned to answer with: “Yes, you too!”’. She continues: ‘This is a fight that I started and I will continue’. How the participants report such problems makes it clear that experiences of discrimination are processed in a differentiated manner.

Subject-family

What participants reported repeatedly is the importance and cohesion of the family, which is perceived as being helpful: ‘For example, with us, I already do a lot at home, like in the household mom earns the money, so to speak, and we have a close relationship, we can talk about everything, so I can tell her everything’ (participant 3). However, the family does not always have to act as a resource: Another participant reported that the demands of the primary family and of the partner are in a strong conflict. The different needs are thus opposed: ‘As a woman, you are worth something when you are still a virgin: That's in the eyes of your family. As a woman, you are worth something when you have sexual experiences. That's in your husband's eyes. Two worlds again’ (participant 42).

Subject-culture Germany

But honestly, that [the training] is not my dream … I didn't succeed in achieving a higher education but I know so many people who are still just after three years looking for something or have done part-time jobs but have no training, do not have a place at university. If you work well, are very hardworking and show commitment, then I think it [finding a great job] should pose no problem either (participant 28).

Subject-culture Turkey

my wish … for the future, is … even with a headscarf, [that] I am in a position where you can say from an outside perspective, she made it so that people don't think only cleaning ladies wear headscarves, but generally … that it is now common to see several Muslim young women in higher positions (participant 20).

Yes, my aunt is a civil servant in Turkey and she does not wear a headscarf, how does that work? Something like this, I would like, that you had an objective world of media, where you just objectively say that this is Turkey, this is Germany, and what I really wish would happen is for the relationship between Germany and Turkey to become normal (participant 33).

Subject-religion Christian

Through my religion [Islam] I have learned how to behave towards other people, that the atheist belongs to it, the Christian belongs to it, the Jew also belongs to it. One accepts someone else because they are the creation of God (participant 33).

Subject-religion Islamic

I wouldn't say that I have to wear a headscarf to show that I am Muslim. For me these are just things, I have respect for them, my boyfriend's mother also wears a headscarf herself, I respect everyone's own choice in this matter (participant 1).

Subject-social Germany

That was the first time when I actually decided on a confrontation and then said ‘ok, something must be done’. That was the connection to founding a political committee with a fellow student from the university dealing with such topics and I perceived it as a racist remark and it drove me mad when people around me said: ‘oh, don't feel offended‘ (participant 1).

This also includes unpleasant experiences from everyday life that irritated the interviewees, such as verbal arguments.

Subject-Social Turkey

The participants’ experiences in the social space of Turkey are mostly made during vacation or study stays. For example, feeling German in Turkey and Turkish in Germany is reported by many participants, including participant 38: ‘But when you are in Turkey, they say to you German. Here they say to you Turk. I would say now, that is nothing bad’.

I was in a mentoring program as a mentee − and I had a mentor who was a law student and a German with a Turkish background. Most of my acquaintances there have not studied … worked their way up there, bought a car and then most of the money goes into insuring the car. And he was one of the most essential characters in my life who showed me that you can make something out of yourself, that you are independent of where you come from (participant 25).

Subject-Institutional Turkey

The participants often reported significant changes that the institutional organizations in Turkey have experienced. They have also made the experience that the reliability of the institutions there varies more than in Germany. Opinions on the role of the Turkish president who is mentioned multiple times vary. It is also often said that the German media criticized the president. As an example, a statement from participant 18 follows: ‘I used to think Erdogan was ok, more or less. But the fact that the German media attacks him like that, makes you feel like as if one had to defend him’.

Open Code: Taking-responsibility

Subject

Taking-responsibility means taking responsibility for oneself, one's way of life and responsibility for others. The high number of codings provides indications of the subjects’ ability to reflect. The subjects are active in a variety of ways and can explain their actions in the context around them and act as mediators so that their environment entrusts them with responsible tasks. They take responsibility for themselves and their own lives: ‘I am in an apprenticeship, I would like to complete it and then take any further training measures and then keep on training, read books, keep up to date’ (participant 2). Regarding the relationship between subject and structure, our participants take on a special degree of responsibility in cooperation with the structure, mostly to ensure that their efforts to integrate are followed by success:

Subject-family

Furthermore, parents simply delegate the responsibility of successful integration to their children: ‘My parents did not give me what I needed to be successful in Germany. I have to work it all out myself, I have to fight hard for everything bit by bit’ (participant 27). The participants repeatedly described their childhood as an important basis on which they were encouraged to take on responsibility: ‘[My grandmother] used to take care of me. She supported me then, now I support her in everything’ (participant 4).

Subject-culture-Germany

German culture is predominantly rated as positive: ‘This structure, this German accuracy, that is something that I have worked on as a discipline and also internalized [and will also help me] for my work’ (participant 9). However, sometimes German culture is perceived as stressful: ‘I was very, very annoyed by the German system. The constant expectation: you have to go to school, then work, leaves you with hardly any free time. I asked myself why I have been working here constantly?’ (participant 23).

Subject-culture Turkey

In the case of Turkish culture, the participants particularly praised the interactive aspect. The subjects learn from an early age how to take responsibility for one another as part of the culture: ‘So the reason why Turkey is so important to me is above all family and its solidarity the feeling of being together’ (participant 12).

Subject-religion Islamic

I cannot imagine myself wearing a headscarf. [Because] I know that this will make my progression through life more difficult. I have not seen a woman wearing a headscarf in a management position or one who works as an engineer in a large company (participant 32).

By continuing to stand by their religion and thus anchoring it more and more in German society, they take responsibility for it and advocate for more equality.

Subject-Social Germany

The participants’ determination is also shown by the fact that they bring the necessary energy to endure in Germany's social structures: ‘My parents did not give me what I needed to be successful in Germany. I have to work out everything myself, fight hard bit by bit’ (participant 27). This is an example of the impression that participants have to fight their way through independently and take on a lot of personal responsibility to have a successful integration. Participant 34 speaks about a discriminatory experience in the social-institutional space: ‘I also had the problem at my school that I was suddenly labelled a terrorist by the teacher because I came to school wearing black clothes’.

Subject-social Turkey

I am a son in the family, who has to be strong, who has to build his own life. That's how it is seen in Turkey … He [the son] has to make something of himself, has to be hardworking, has to study, has to properly care for his family. After my father had a heart attack, he said that when he is no longer alive that I will be the one responsible for taking care of the family; that was very direct, very hard (participant 15).

Subject-institutional Germany

For my life: security for me, my family and prosperity and I think the rest will then fall into place, these are very important factors. I envision Germany in its full multicultural potential. That you respect others and their way of life (participant 10).

At the same time, many participants also reported discriminatory experiences they have had with government agencies in Germany: One person stated how she felt devalued due to her poor grade in German class: ‘My German teacher thought that I couldn't speak German and that you should have it checked by the immigration authorities in retrospect that was my first confrontation with everyday racism’ (participant 1).

Subject-institutional Turkey

If I could wish for something? That people wake up! It was unfair that people couldn't go to the polling station. [I hope] that things are moving more in the direction of democracy in Turkey again and not moving away from it bit by bit … That would be very important to me (participant 7).

DISCUSSION

In our study, we asked 50 young Muslims questions about the subject constitution and the relationship between subject and the intra-subjective as well as inter-subjective structure. The most common open codes that we assigned were constructive: ‘feeling-held’, ‘being-able-to-process-experiences’ and ‘taking-responsibility’. Many participants describe intact and close family relationships, calling the family the most important thing in their life. They describe how they can deal with positive and negative experiences. They need to take responsibility for their own lives and others. Concerning the successful educational status of our participants, we would like to derive the hypothesis from this finding that this triad represents typical features for successful professional integration: those who feel they are at home in their Turkish family or in the Islamic religion can process (negative) experiences and have (mature) superego structures. A person being-able-to-take-responsibility both for him-/herself and for others will also be able to deal with the challenges of migration more easily than a person who does not have these resources. Since we have not aggregated enough data for the group of young people affected by some form of disintegration, a possible theoretical link should be considered. In discussing radicalization, Benslama (2017) notes that these young people (predominantly being male) have given up their freedom in order to relieve themselves from confusing feelings, fears about life, and disorientation. They begin to use religion to eradicate everything feminine in themselves and to disguise themselves with a toxic masculinity. In doing so, the reduction of the Islamic religion to the political issues abuses the idealism of the young people and leads to the erasure of their individuality. Being a member of a radicalized group, the subject attains a sense of ‘infinite power’ (see also Freud, 1921).

This leads to a self-hating and inhuman ideology. It seems understandable that this group of young people would not have felt addressed by an invitation to participate in a scientific study. Nevertheless, future studies should be conducted with these groups, as the description of their inner lives can provide valuable insights.

The interviews show that the ability to triangulate between the subject and two structures or systems may be helpful for a successful integration. This is our first hypothesis. Many participants reported that they were able to maintain a good relationship with their Turkish culture and their family as well as with German culture and society. They can use the advantages of both Turkish and German structures. This development is initiated by an atmosphere in which the participants feel that they are being held by the others, that is, by the social environment of the family. In this safe atmosphere, a basis is formed on which they can process their experiences. The reflection process allows them to take on responsibility. They can reach a mature position in which the subject is able to integrate into both countries.

This sets up the second hypothesis: Those who can shape their world triadically have a greater chance of integrating themselves successfully. It is the oedipal triad in which the child (subject) has an individual relationship to both the mother and the father, that is, can integrate two early objects and recognize them as independent and individual (Rohde-Dachser, 1987). However, some participants tend to have dyadic relationships. They experience the outer world as more or less divided, that is, into ‘familiar’ and ‘foreign’, into ‘appreciative’ and ‘devaluing’. A study by social scientist Ruud Koopmans (2015) carried out with Muslims in six European countries revealed that around half of the respondents are convinced that the West wants to destroy Islam. A mature resolution to the Oedipus complex would be to abstain from incestuous (dyadic) relationships and to love the parent with whom the child had rivalled (Freud, 1924; Rohde-Dachser, 1987). Applying this to migration means renouncing the incestuous relationship with one culture/society and loving or recognizing the other, alternative culture. This resolution of the Oedipus allows the participant to obtain what they need from both cultures. We suggest that this process is the real integrative effort that young Muslims need to achieve.

Above all it seemed that the participants experienced verbal discrimination. However, subjects with a triadic model perceive racism as less threatening or place positive aspects of German structures at the forefront. Racial discrimination means castration. André Green (2001) distinguished between a ‘narcissistic’, dyadic castration and an ‘oedipal’ castration belonging to the triad. For the participants who reported dyadic constellations, racial discrimination represents a higher burden as ‘narcissistic’ castration. Accordingly, they react angrily and prefer Islamic culture and religion or distance themselves from the German culture. While participants reported that there certainly are experiences of discrimination in Germany, their visit to Turkey conveyed experiences of alterity: they are not of less value in Turkey but nonetheless feel to a certain extent a bit foreign. Despite these experiences of alterity, the environment in Turkey is described as rather positive and affectionate.

Above all, integration appeared to be an intra-psychic process and not only the external adaption to the demands of the big Other. Most of the young Muslims we interviewed reported a very pronounced adjustment. They were rather well adjusted to the Western system or structures. They displayed a strong willingness to perform successfully and a high level of commitment and enthusiasm. This shows the double-faced nature of the Oedipus: On the one hand, it enables successful social integration. On the other hand, the Oedipus stands for the patriarchal structure that requires adaptation, in that case to the Western capitalist system. There is a wide range of ‘Oedipus-critical’ literature (Deleuze & Guattari, 1977; Tutt, 2014) that problematizes this adaptation in the sense of subjection. This point of view addresses the problems of the goals of today's strongly propagated ‘integration’, which should not be limited to a mere adjustment, but should rather promote the subject's freedom, self-determination and autonomy. To initiate this development, the ‘host country’ should realize a tolerant and cosmopolitan culture of recognition.

All in all, the oedipal constellation which is maintained by the threat of castration in both the Freudian and Lacanian perspectives, allows the passage from the Imaginary to the Symbolic, and it prevents at the same time the subject's return to the dyad. In this respect, the Oedipus complex is the guardian of a successful psychosocial integration, which takes place both intra-subjectively (as a psychodynamic prerequisite) and inter-subjectively − in the German or, as generally spoken, in the Western society. By imposing this oedipal triangulation, the incestuous as the final consequence of an extremely close relationship with ‘Turkey’ or ‘Germany’ is rendered impossible. On the other hand, however, opportunities for identification are subsequently opened up.

It seems to us that the big Other, which in one way or another can be traced back to the primary objects, unfolds with various facets in terms of the German and Turkish structures. The ‘German big Other’ seems to be secular: This structure is characterized by the demand for punctuality, reliability and diligence. In the interviews, these German or Prussian ‘secondary virtues’ (‘Sekundärtugenden’) were mentioned again and again, mostly with praise. However, the big Other that unfolds in Turkish culture is religious. In this case the big Other is the Islam, God or an imam. Or the big Other functions politically: As a powerful, warlike person, from Mehmed I, who conquered Constantinople, to the current Turkish President. Lacan made no distinction with regard to the threat of castration from Freud's conception of the Oedipus complex. His opinion was that the child, regardless of its gender, desires the mother, and the father stands in the way of such incestuous wishes (Evans, 2006, p. 130). From this perspective it is conceivable that the big Other (be it the secular-German or the spiritual-Turkish) prevents an incestuous-amalgamating relationship to the other country or culture.

So, the subject could strike a balance between adapting to the intrasubjective/intersubjective structure and developing a self-determined and autonomous attitude. This is one of many experiences that could be used to raise awareness among mental health professionals about the specifics of what is going on within this potential patient group. This could be done in book or app form, and thereby provide professionals additional leverage on establishing a good therapeutic relationship with their patients.

Finally, we want to place our results and hypotheses explicitly in the context of Lacan's subject theory, as laid down in Scheme L. Lacan conceptualized the relationship between the subject and the structure, that is the imaginary or symbolic other (big Other) with the graph of the ‘Lambda schema’ or ‘Scheme L’ (Lacan, 1991a, pp. 142–3, 1991b, p. 243; see Figure 1). In our study there is the big Other (A): The parental laws that determine the unconscious of the subject (S), as well as the social, normative and religious ideas in both Turkish and German structures/systems (culture, society). The laws of the big Other (A) generate the ‘symptoms’ in the subject (S). It seems to be beneficial for the integration if the subject can form a triad with the big Other by using the ‘Turkish-influenced’ big Other (the ‘Turkish big Other’) as well as the ‘German-influenced’ big Other (the ‘German big Other’). Subjects who can triangulate themselves with the help of the triad are more often able to integrate both parts. They don't have to split off their Turkish-German world. The big Other of the West, however, is today among other things determined by the decline of Oedipus, that is, of the patriarchal-religious system and the enjoyment of the surplus-value being staged by the Western-capitalistic way of life (Mura, 2014; Žižek, 2000, 2017).

We see the feeling of being held primarily situated on the imaginary axis. Many of the young Muslims we interviewed felt appreciated and indeed admired by their families. Winnicott (1960) described the feeling of being held as an expression of a primary maternal function, emphasizing the bodily aspect of the children's security. We think that the feeling of being held arises mainly from the positive mirroring on the imaginary axis, but also from the influence of a benevolent big Other which uses a tender language. In this sense, our participants also had a strong desire for the imaginary acknowledgment from German society. On the other hand, the desire of the (native) racist (a) to devalue the other (a’) may be fed by the wish that the other (i.e. the migrant) should be like himself. If the other not like him, they must be destroyed or devaluated because there is no chance of mirroring (for the native racist). This may be the psychological mechanism that the migrant is not mirrored by the native other (a’) or condemned by the big Other (A).

This conflict is exacerbated by forcing Muslims to commit themselves as Muslims or Europeans. From this point of view, it may be difficult to develop an ambiguous, multi-faceted ego (a) and come to terms with the big Other (A) of their own or the foreign culture. Abdel-Samad (2018, p. 23) states: ‘The mainstream theology of Islam and the tribal mentality force Muslims to define themselves either as Muslim or as European’. The individual is thereby forced to decide for or against the Islamic imaginary identity (a’) − as well as for or against the European or Islamic big Other. Participant 48, for example, switched from the profession of teacher to the field of pharmacy because she feared that she would not be hired (i.e. not recognized) as a teacher while wearing a headscarf. In fact, the German Constitution (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2020) states (Article 4 GG): ‘(1) The freedom of belief, conscience and the freedom of religious and ideological confession are inviolable … The undisturbed practice of religion is guaranteed’ and in Bavarian Law (Recht, 2015) (Article 59 BayEUG) ‘External symbols … which express a religious … conviction, may not be carried by teachers … if … [they are not compatible with] the Christian-Western educational and cultural values’.

In contrast to a pharmacist, a teacher with a headscarf does not correspond to the imaginary conceptions of the ‘Christian population’. The headscarf destroys the mirror effect and must be banned. The participant seems to be well aware of the racism she will be subjected to by the German Other. It is, however, precisely a sign of triadic flexibility that this young lady swiftly responds to this discrimination by deciding to pursue an alternative profession. She does not feel abandoned, processes her experiences and bears responsibility for her professional career. Overall, we saw that both imaginary and symbolic aspects play a role in the integration process, corresponding to the aspects of Lacan's Borromean knot.

The Borromean knot … so called because the figure is found on the coat of arms of the Borromeo family, is a group of three rings which are linked in such a way that if any one of them is severed, all three become separated … Strictly speaking, it would be more appropriate to refer to this figure as a chain rather than a knot, since it involves the interconnection of several different threads, whereas a knot is formed by a single thread. Although a minimum of three threads or rings are required to form a Borromean chain, there is no maximum number; the chain may be extended indefinitely by adding further rings, while still preserving its Borromean quality (i.e, if any of the rings is cut, the whole chain falls apart).

Religion as a good and nourishing introject can been seen as a part of the Imaginary. Religion – in the shape of words, prayers or Quran verses – is also part of the symbolic big Other. The real, predominantly unrepresented aspects of the migration experience cannot be directly inferred from a qualitative-linguistic investigation. We believe, however, that the emotional powerful intensity of some reports about discrimination or the bodily symptoms (e.g. dizziness) might be the felt echoes of Lacan's real.

Regarding the study's limitations, it should be mentioned that the majority (74%) of the participants were students. Therefore, a sample bias exists. This reticence is well known. Abdel-Samad (2018) cites reasons such as fears that the participants’ reports could perhaps be abused by a security service or that the participants may get in trouble with the judiciary. There is also a fear within the community of being stigmatized as a ‘net polluter’ (Abdel-Samad, 2018, p. 104). ‘In the end’ according to Abdel-Samad (2018, p. 29), two types remain: The ‘cosmopolitan Muslims’ who had nothing to hide and those who answered the questions in the sense of social desirability. Most of our participants embraced their dual national heritage. This has a direct impact on our study: those young Muslims living in ghettos, parallel societies, struggling with social misery, crime, unemployment, and under the observation of ‘moral guards’ (Abdel-Samad, 2018, p. 95) could not be included in our study. Thus, we present a group of young Muslims who have mostly managed to enthusiastically progress in Western society with a high level of commitment, while still having an awareness of the problems. It should therefore be emphasized that the results of this study are to be understood as statements about this sample of well-integrated Muslims. Further studies should investigate whether these phenomena can also be found within the group of less well-integrated Muslims. At a first glance, we have distinguished between subject and social structures. With the help of Lacan's subject theory, however, we were able to understand that the integration of young Muslims is not a matter of external versus inner processes. In contrast, however, the subjective structure in which the integration processes take place includes the positions of the subject of the unconscious (S), the ego (a) as well as the symbolic big Other (A) and the imaginary other (a’). These four cornerstones mark the playing field on which young Muslims move and are thereby shaping their lives today.

NOTE

Biographies

PAUL MAXIMILIAN KAISER, PhD, obtained a Bachelor of Science in psychology and a Master of Science in clinical psychology at MSH Medical School Hamburg, Germany. In 2018 he became a postgraduate in psychological psychotherapy at HIP HafenCity Institute for Psychotherapy, Hamburg, focusing on psychodynamic therapy and psychoanalysis. In the same year he went on to write his doctoral thesis at University of Luebeck and was awarded a PhD Scholarship by MSH Medical School Hamburg. In 2021 he received his doctorate. He is a scientific fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Psychoanalysis and Cultural Studies (IPPK) in Berlin. His research interests concern the intersection between migration, culture and psychoanalysis. Address for correspondence: [[email protected]]

LENA BARTH, MSc, completed her Bachelor of Science in Psychology at the London Metropolitan University and completed her Master of Science in clinical neuropsychology in Magdeburg. She completed further training as a psychological psychotherapist at the Hannover Medical School. She is a psychotherapist in private practice, lecturer and researcher. She is supervisor of the postgraduate training on psychodynamic therapy at the HIP HafenCity Institute for Psychotherapy and at the Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE). She is also a PhD student focusing on the topic of identity development and the experience of integration in the context of globalization and changing values among young Muslims.

GONCA TUNCEL LANGBEHN, Dip Psy, studied psychology at the University of Hamburg, and then trained as a psychological psychotherapist in psychodynamic therapy. She worked as a psychologist at the Clinic for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy and organized psychoeducational seminars for parents and children. In addition, she collaborated on a Turkish-German radio show on psychological topics, and started a study on identity development and the experience of integration in the context of globalization and changing values among young Muslims.

BARBARA RUETTNER, MD, is a medical specialist in psychiatry and psychotherapy, and a university professor at MSH Medical School Hamburg for clinical psychology and analytical psychotherapy. She completed psychoanalytic training at the Freud Institute in Zurich, is a psychoanalyst, and supervisor of the postgraduate course on psychoanalysis at the HIP HafenCity Institute for Psychotherapy, Hamburg. Her main research focus is on investigation of unconscious phenomena in interviews and images with the help of qualitative data analysis in different patient collectives (somatoform pain disorders, heart attack patients, patients after lung transplantation). She also has her own psychoanalytic practice. She has published articles in the field of psychoimmunology and psychosomatics.

LUTZ GOETZMANN, MD, is a medical specialist in psychiatry and neurology, a psychotherapist and psychoanalyst habilitation at the University Hospital Zurich focusing on psychosomatic aspects of transplant medicine. She completed psychoanalytic training at the Freud Institute in Zurich and in 2011 − 20 she was head physician at the Clinic for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy. Since 2021 she has had a private psychoanalytic practice in Berlin (IPPK). She is also co-editor of the magazine Y (magazine for atopic thinking). She has published numerous articles in the field of psychoanalytic psychosomatics.