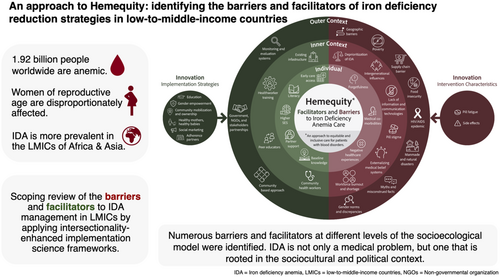

An approach to Hemequity: Identifying the barriers and facilitators of iron deficiency reduction strategies in low- to middle-income countries

Summary

Approximately 1.92 billion people worldwide are anaemic, and iron deficiency is the most common cause. Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) disproportionately affects women of reproductive age and remains under-addressed in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs). The primary objective of our scoping review is to evaluate the barriers and facilitators to IDA management in LMICs by using an intersectionality-enhanced implementation science lens adapted from the consolidated framework for implementation research and the theoretical domains framework. A total of 53 studies were identified. Contextual barriers included the deprioritization of IDA risk, unequal gender norms and stigma from the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Regional poverty, conflict and natural disasters led to supply chain barriers. Individual-level facilitators included partner support and antenatal care access while barriers included forgetfulness and having medical comorbidities. Successful interventions also utilized education initiatives to empower women in community decision-making. Moreover, community mobilization and the degree of community ownership determined the sustainability of IDA reduction strategies. IDA is not only a medical problem, but one that is rooted in the sociocultural and political context. Future approaches must recognize the resilience of LMIC communities and acknowledge the importance of knowledge translation rooted in community ownership and empowerment.

Graphical Abstract

Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) disproportionately affects women of reproductive age and remains under-addressed in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs). The primary objective of our scoping review is to evaluate the barriers and facilitators to IDA management in LMICs by using an intersectionality-enhanced implementation science lens. Our results highlight that IDA is not only a medical problem, but one that is rooted in the sociocultural and political context. Future approaches must recognize the resilience of LMIC communities and acknowledge the importance of knowledge translation rooted in community ownership and empowerment.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout this article, we predominantly use the term ‘women’ to highlight care gaps and global health inequity among women. We acknowledge that these terms are exclusive and ask the reader to recognize that these experiences may also apply to all people with the anatomy that allows for menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth, including girls, transgender men, intersex people and gender nonbinary individuals.1

Approximately 1.92 billion people worldwide are anaemic with iron deficiency accounting for more than half of the global anaemia burden.2, 3 Women of reproductive age (WRA) are disproportionately affected given predisposing risk factors of menstrual blood loss, pregnancy and childbirth.4, 5 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 539 million non-pregnant women and 32 million pregnant women globally are anaemic.6 In low- to middle-income countries (LMICs), the WHO regions of Africa and Southeast Asia have the highest prevalence of anaemia, where 40.4% and 46.6% of WRA, respectively, are anaemic. This is nearly triple the prevalence of anaemia in WRA in high-income regions, which are 15.4% in the Americas to 18.8% in Europe.7

In 2021 alone, anaemia caused 52.0 million years lived with disability (YLD) and is the greatest source of YLD in WRA.2 Anaemia reduces cognitive performance and economic productivity and is associated with increased risk of severe morbidity and all-cause mortality.8-10 While iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is a correctable problem, it remains under-addressed globally. A recent trial showed that pre-existing uncorrected anaemia is the main driver of maternal deaths in LMICs.11 IDA is also cyclical and compounding with evidence of intergenerational transfer of poor iron status, where antenatal IDA predisposes to IDA in infancy.12-14 This highlights the negative consequences of ‘hidden hunger’, a term used to describe the presence of micronutrient deficiencies, which further perpetuates structural sexism and racism and the loss of human capital.15

Despite abundant evidence that iron replacement is an effective and life-saving intervention, there is little understanding of how to deliver it effectively in LMICs and its diverse health systems. LMIC populations have unique predisposing risk factors and barriers towards the implementation of disease reduction strategies requiring the application of a public health lens that considers IDA's inherent sociocultural and political complexities. In addition to nutritional deficiencies, helminth infections and malaria contribute significantly to anaemia through impaired iron absorption, metabolism and increased losses.5, 16, 17 The higher prevalence of inherited red blood cell disorders in LMICs has also made the role of widespread iron intervention programmes uncertain given the risk of iron overload in those with severe disorders.5

Multiple studies have explored the efficacy of different interventions in the LMIC setting such as iron supplements, micronutrient powders, iron-fortified food products and iron cooking pots.18-21 Yet, large-scale programmes have failed to achieve sustainability due to supply chain breakdowns as well as low adherence and uptake within various LMIC communities.22 This highlights the need for further evaluation of the literature to better inform the development of public health interventions, healthcare policies and guidelines towards global IDA control. The overarching aim of our scoping review is to evaluate the barriers and facilitators to IDA management in LMICs by using an intersectionality-enhanced implementation science lens adapted from the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) and the theoretical domains framework (TDF).

METHODS

Given the complex nature of this topic, a scoping review methodology was used. This scoping review was designed following the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis extension to scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines,23 and the methodology as described by the Joanna Briggs Institute.24 The review protocol was registered on Open Science Framework.25

Search strategy

We conducted a database search of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase and Scopus as well as a manual search of the grey literature including clinical trials (clinicaltrials.gov, EU clinical trials register), conference abstracts from the American Society of Hematology, and WHO's library databases (WHOLIS, Global Index Medicus) from inception until 27 December 2023. The citations of included papers were also searched to identify relevant articles. The search strategy was developed with a medical librarian and in accordance with the PRESS 2015 checklist.26 A combination of keywords and subject headings related to the concepts of IDA and LMICs was used in the database search. The full search strategy can be found in Supporting Information S1.

Study selection

Studies were included if they met all the following inclusion criteria: (1) included WRA (15–49 years)7 or adolescent girls (10–19 years),27 who are at risk of developing or have established IDA; (2) assessed the development, implementation and/or evaluation of strategies increasing oral iron intake and bioavailability; and (3) conducted in an LMIC, as defined by the World Bank.28 Editorials, popular media, case reports, case series and non-English articles were excluded. Title/abstract and full-text screening were completed through an independent and duplicate process by two reviewers (SG and SA) using Covidence. Discrepancies were resolved via consensus between the reviewers and adjudicated by a third reviewer as necessary. A randomized 10% sample of studies was selected for pilot calibration to ensure reviewer consistency.

Data charting and extraction

Data extraction was completed independently by two reviewers (SG and SA) and discrepancies were resolved through consensus and mediated by a third-party reviewer, as needed. The following information was collated: first author name; year of publication; journal of publication; country of implementation; study design; patient demographics; intervention details; behavioural, clinical, patient-oriented and process outcomes; and identified barriers and facilitators.

Data synthesis

We were guided by the intersectionality-enhanced version of the CFIR,29 and the TDF in our data synthesis.30 Our modified approach has been used to develop interventions to address iron deficiency in pregnant patients. This funded work is currently underway and is based on the a published Canadian study, which developed a novel toolkit entitled: iron deficiency in pregnancy with maternal iron optimization (IRON MOM) .31 Similar adaptations of the CFIR categories have been applied in previous research in the LMIC setting by the study authors.32 The CFIR is a comprehensive framework to predict and understand barriers and facilitators to implementation effectiveness through an intersectionality lens. It consists of five core domains: outer setting, inner setting, individuals, process and innovation.29 The TDF is comprised of theories of behaviour change clustered into 14 domains and examines the cognitive, affective, social and environmental influences on health behaviour.30 We conducted a thematic analysis and organization of the included studies based on study measures and reported outcomes. Following a framework analysis,33 our study combined both deductive and inductive approaches to coding where codes were developed based on CFIR and TDF domains and subconstructs as well as repetitive themes that emerged from included studies. Codes with interrelated concepts were then grouped into categories to create a working analytical framework. The data were then charted into a matrix generated in an Excel spreadsheet, and interpretation of the data was reviewed in an iterative process by the authors (SG, GHT and MS).

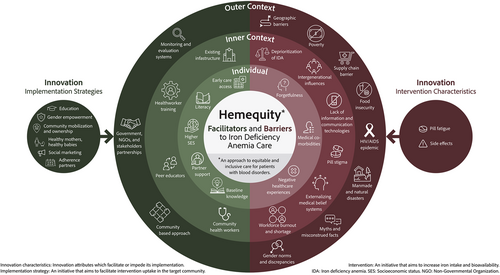

In our narrative synthesis, we developed the following adapted CFIR and TDF categories to highlight the different levels of identified barriers and facilitators: (1) outer context, (2) inner context, (3) individual and (4) innovation. The outer context is factors within the broader socioeconomic and cultural context that shape how the innovation is delivered. The inner context is factors examining how models of care are shaped by the health infrastructure and surrounding community. Individual characteristics are personal attributes that influence how the individual interacts with the innovation. Lastly, innovation characteristics describe the qualitative data facilitating or impeding innovation implementation. An innovation is defined as a novel IDA reduction strategy being introduced; this can be either an intervention or implementation strategy.34 An intervention is defined as an initiative that aims to increase oral iron intake and bioavailability, the most common example being oral iron supplementation. An implementation strategy is an initiative that aims to facilitate the intervention's uptake in the target community. The definitions of the adapted CFIR and TDF categories are summarized in Table 1.

| Category | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Outer context | Factors within the broader socioeconomic and cultural context that shape how the intervention is delivered |

| Inner context | Factors examining how models of care are shaped by the health infrastructure and surrounding community |

| Individual characteristics | Personal attributes that influence how the individual interacts with the intervention |

| Innovation characteristics | Attributes of the innovation which facilitate or impede innovation implementation |

| Intervention | An initiative that aims to increase oral iron intake and bioavailability |

| Implementation strategy | An initiative that aims to facilitate intervention uptake in the target community |

- Abbreviation: CFIR, consolidated framework for implementation research.

Given the primary purpose of a scoping review is to map the available evidence and identify common themes, a risk of bias assessment and quality appraisal were not completed. This is in accordance with scoping review methodology.23, 24

RESULTS

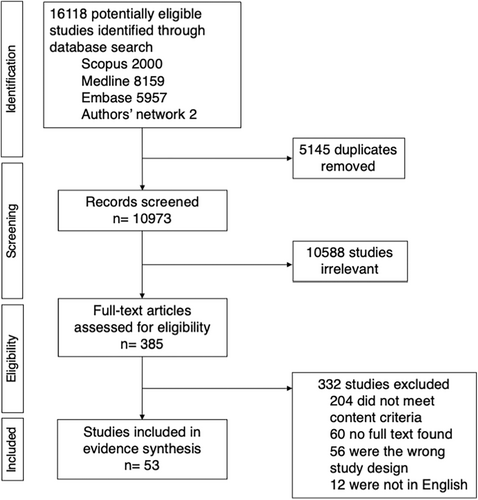

Of the 16 118 potentially eligible studies identified from the database search, 53 studies were included in the final evidence synthesis (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

A total of 53 studies were included and published between 2002 and 2023. Of the 53 studies, 53% (28/53) were implemented in Africa, 40% (21/53) in Asia, 4% (2/53) in South America and 2% (1/53) in the Middle East. One of the studies encompassed participants from Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Methodology of the included studies included randomized control trials (8/53), quasi-experimental (4/53), cohort (10/53), cross-sectional (20/53), qualitative (7/53) and other miscellaneous study designs including process evaluation studies (1/53), trials of improved practices (1/53) and programme evaluation reports (2/53). Study populations included pregnant women, non-pregnant WRA, as well as healthcare workers, community health workers (CHWs) and family members composing the women's support system. A full description of the included studies is summarized in Table 2. Barriers and facilitators of IDA reduction strategies are summarized in Figure 2.

| Author (year) | Country | Study design/population | Interventions (if applicable) | Key findings/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic region: Africa | ||||

| Alaofè et al. (2009)99 | Benin | Quasi-experimental study Adolescent girls | Education programme and increase in dietary iron | Education programmes on IDA and dietary intake of iron should be included in the school curriculum |

| AregaSadore et al. (2015)54 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Side effects, perceived supply shortages and forgetfulness were associated with poor compliance. ANC visits, knowledge and counselling were associated with adherence |

| Asres et al. (2022)100 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Having four or less children, living less than 30 min from ANC facilities, early initiation of IFA supplements and health counselling were associated with adherence |

| Assefa et al. (2019)38 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | System barriers included inadequate supply and long wait times. Health education, prior abortion and knowledge were associated with adherence |

| Balcha et al. (2023)72 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplementation, dietary changes, deworming, bed nets | Maternal social demographics including higher education level, smaller family size and knowledge of anaemia were associated with adherence |

| Beressa et al. (2022)67 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

Iron supplements | Literacy, absence of side effects, free access to iron supplements and education programmes were associated with adherence |

| Byamugisha et al. (2022)70 | Uganda |

RCT Pregnant women |

IFA supplements in blister packs | Blister packaging did not have a significant effect on IFA adherence or changes in haemoglobin |

| Cliffer et al. (2023)69 | Burkina Faso |

RCT Adolescents |

School-based supplementation | Supplements alone did not significantly increase haematological indices and should be combined with other cointerventions. Schools can be utilized as a delivery tool |

| Koné et al. (2023)80 | Cote d'Ivoire |

RCT Pregnant women |

Combined IFA supplements and malaria prophylaxis with education and home delivery services | Counselling with direct home delivery of supplements improved malaria prophylaxis and IFA supplement coverage |

| Demie et al. (2023)78 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

Iron supplements | High education level was associated with adherence. Late initial ANC visits were associated with lower compliance |

| Gebremichael et al. (2020)53 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Nutrition counselling, partner support and knowledge were associated with adherence |

| Digssie Gebremariam et al. (2019)76 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Counselling, knowledge, early ANC attendance and anaemia diagnosis were associated with adherence |

| Getachew et al. (2018)37 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women (in refugee camps) |

IFA supplements | Lack of counselling and knowledge were associated with lower compliance. Having four or more ANC visits was associated with adherence |

| Gosdin et al. (2021)71 | Ghana |

Prospective cohort study Adolescent girls |

School-based IFA supplements and integrated health and nutrition education | A school-based integrated IFA supplementation programme was a promising intervention to address IDA burden with improvement in haematological indices |

| Kamau et al. (2019)68 | Kenya |

Quasi-experimental study Pregnant women |

IFA supplement and counselling provided by CHWs | Implementation of a community-based health education positively influenced change in knowledge, acceptance and compliance of IFA supplements |

| Kamau et al. (2020)41 | Kenya |

Qualitative study Pregnant women, CHWs, nurses |

IFA supplement and counselling provided by CHWs | Integration of a community-based approach for IFA supplements using CHWs was successful |

| Kiwanuka et al. (2017)40 | Uganda |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

Iron supplements at ANC visits | Prior health education and having four or more ANC visits were associated with adherence. Inadequate supply and side effects were associated with low compliance |

| Martin et al. (2017)50 | Ethiopia, Kenya |

Trials of improved practices Pregnant women |

Adherence partners | Adherence partners are an acceptable, low-cost strategy with the potential to support supplementation adherence |

| Molla et al. (2019)55 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Having four or more ANC visits, knowledge and prior anaemia history were associated with adherence |

| Seck et al. (2008)56 | Senegal |

RCT Pregnant women |

Iron supplements | Compliance with IFA supplementation is increased through counselling and education about its health benefits and side effects |

| Tegodan et al. (2021)43 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Non-adherence was associated with lack of education, comorbidities, forgetfulness, side effects, pill burden and fatigue |

| Tinago et al. (2017)51 | Zimbabwe |

Qualitative study Pregnant women Healthcare workers |

IFA supplements | Reasons for low compliance included forgetfulness, GI side effects, stigma from the HIV/AIDS epidemic, misinformation and social norms. Future approaches need to address individual and structural factors |

| Tsegai et al. (2023)73 | Eritrea |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Having more than four ANC visits and planned pregnancies were associated with adherence. Health workers were the main source of information |

| Wakwoya et al. (2023)101 | Ethiopia |

RCT Pregnant women |

Education programme with counselling sessions, text messages and leaflets. | The education programme led to an increase in dietary iron, increased haemoglobin levels and decreased anaemia prevalence |

| Wana et al. (2020)48 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Future interventions need to be integrated at all levels. CHWs and health providers were effective in counselling on IDA and increasing ANC attendance |

| World Vision (2006)35 | Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawai, Senegal, Tanzania |

Not applicable—final programme report Women of reproductive age, children less than 5 years of age |

Multicountry nutrition programme to target IDA and other nutritional deficiencies | Successful and sustainable programme interventions required multisector collaboration, continual monitoring systems, community ownership and experience sharing |

| Yalew et al. (2023)75 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Individual factors affecting compliance included education status, ANC follow-up and number of children. Contextual factors include living in regions with ANC follow-up |

| Yismaw et al. (2022)74 | Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Maternal knowledge, awareness of anaemia and early ANC visits were associated with adherence |

| Geographic region: Asia/Southeast Asia | ||||

| Adhikari et al. (2009)81 | Nepal | RCT pregnant women | Iron supplements and education programme | Education programme with iron supplements increased haemoglobin, decreased anaemia prevalence and improved compliance and knowledge |

| Baizhumanova et al. (2010)102 | Kazakhstan | Prospective cohort study Women of reproductive age, children | Communication campaign and wheat flour fortification | A communication and health education campaign prior to the fortification programme improved haematological indices |

| Berger et al. (2005)63 | Vietnam |

Prospective cohort study Women of reproductive age |

IFA supplements and community-based social mobilization and marketing | IFA supplements with social mobilization and marketing were effective in preventing and controlling IDA before and during pregnancy |

| Bhattarai et al. (2023)46 | Nepal |

Qualitative study (mixed methods) Pregnant women |

mHealth virtual counselling on IDA prevention | Multicomponent interventions were recommended given intrahousehold and gender inequalities to address IDA barriers for women |

| Chakma et al. (2013)60 | India |

Prospective cohort study Adolescent girls |

IFA supplements and social mobilization | The use of school teachers and anganwadi workers as supervisors was associated with adherence. Social mobilization allowed for project acceptability |

| Crape et al. (2005)64 | Cambodia |

Prospective cohort study Women of reproductive age |

IFA supplements and social marketing | Social marketing combined with IFA supplements improved haemoglobin levels but was found to be less effective in low SES populations |

| Diamond-Smith et al. (2016)36 | India |

Qualitative study (mixed methods) Pregnant women |

IFA supplements, dietary management | Lack of supply and food, cultural beliefs and low decision-making power in the household were associated with poor compliance |

| Dongre et al. (2011)59 | India |

Prospective cohort study Adolescent girls, children |

Iron supplements and nutrition education | This community-led initiative improved haemoglobin status, knowledge and compliance in adolescent girls |

| Felipe-Dimog et al. (2023)77 | Philippines |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

Iron supplements | Education, high SES, early ANC visits, peer support and free maternal services were associated with adherence |

| Kanal et al. (2005)66 | Cambodia |

Prospective cohort study Women of reproductive age |

IFA supplements combined with social marketing and community mobilization | A multisectoral collaborative approach to IDA was feasible and effective in prevention of IDA and should be expanded |

|

Khan et al. (2005)52 |

Vietnam |

Prospective cohort study Women of reproductive age including pregnant women |

IFA supplements combined with community-based social mobilization and marketing | Application of a social marketing and mobilization approach was feasible and improved the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of iron supplements in women of reproductive age |

| Lutsey et al. (2008)39 | Philippines |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Earlier ANC visit, perceived benefit and health knowledge were associated with adherence. Side effects were associated with poor compliance |

| Nahrisah et al. (2020)47 | Indonesia |

Quasi-experimental study Pregnant women |

Pictorial handbook on IDA and iron supplementation | Education through the pictorial handbook was associated with improved haemoglobin levels, knowledge of anaemia and IFA supplement compliance |

| Paulino et al. (2005)42 | Philippines |

Prospective cohort study Women of reproductive age |

IFA supplements with community-based social marketing and mobilization | Taking a community-based social marketing and mobilization approach was associated with improved compliance with IFA supplements |

| Paratmanitya et al. (2023)82 | Indonesia |

RCT Women of reproductive age |

IFA supplements and mentoring programme with health education and reminder texts | The mentoring programme increased IFA supplement intake during pregnancy |

| Risonar et al. (2009)65 | Philippines |

Prospective cohort study Pregnant women |

Iron supplement and health education delivered by CHWs | This delivery system improved haemoglobin indices, compliance with iron supplements and attendance at ANC visits |

| Sedlander et al. (2020)44 | India |

Qualitative study Women of reproductive age, husbands, mothers-in-law, key informants |

IFA supplements | Barriers at different levels of socio-ecological model influenced IFA supplement compliance. Unequal gender norms, misconceptions and low perceptions of anaemia prevalence were common themes |

| Sedlander et al. (2021)45 | India |

Qualitative study Women of reproductive age, husbands, mothers-in-law, key informants |

IFA supplements | Unequal gender norms significantly impacted anaemia prevalence and IFA supplement adherence |

| Triharini et al. (2018)57 | Indonesia |

Cross-sectional study Pregnant women |

Iron supplements | Perceived barriers included forgetfulness and side effects. Perceived benefits included foetal health and preventing labour complications |

| Widyawati et al. (2015)103 | Indonesia |

Quasi-experimental study Pregnant women |

Four pillars approach to ANC by midwives | This approach was effective in increasing haemoglobin levels and frequency of ANC visits compared to usual care |

| Winichagoon et al. (2002)49 | Thailand |

Not applicable—programme report Pregnant women, schoolchildren |

Iron supplements, educational messages, CHW counselling | Lack of access and misconceptions about iron supplements by pregnant women and service providers contributed to low compliance. Future strategies should include women of reproductive agents, adolescents and young children |

| Geographic region: South America | ||||

| Crispino et al. (2020)61 | Mexico |

RCT Women of reproductive age |

School-based intermittent delivery system of iron supplements | School-based intermittent delivery of iron supplements was effective in highly marginalized Indigenous populations |

| Zavaleta et al. (2014)58 | Peru |

Prospective cohort study Pregnant women |

IFA supplements | Being primipara, experiencing side effects and forgetfulness were associated with lower compliance |

| Geographic region: Middle East | ||||

| Kheirouri et al. (2014)62 | Iran |

Process evaluation study Adolescent girls |

Nationwide school-delivered iron supplementation programmes | School-based interventions required adequate health services and training of teachers to ensure programme effectiveness |

| Geographic region: Multiple | ||||

| Karyadi et al. (2023)79 | Countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Caribbean, not otherwise specified |

Cross-sectional study Women of reproductive age |

Iron supplements | Having four or more ANC visits was associated with adherence across multiple regions. ANC was the most important predictor of adherence to iron supplement intake |

- Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; CHW, community health workers; IDA, iron deficiency anaemia; IFA, iron folic acid; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SES, socioeconomic status.

Types of innovations

The innovations are summarized in Table 2 with a more extensive table describing study characteristics available in Supporting Information S1. Interventions increasing iron intake and bioavailability included food fortification, dietary diversification and iron supplementation. Insecticide-treated bed nets, anti-malarial and anthelmintic drugs aimed at reducing the prevalence of diseases affecting micronutrient status were also described. Initiatives building local capacity for iron supplement delivery systems used schools, antenatal clinics and CHWs as delivery tools. Furthermore, education programmes such as take-home brochures, peer-to-peer mentorships and counselling by CHWs or healthcare providers were reported. Social mobilization approaches included strengthening women's social support through adherence partners as well as employing marketing tactics such as television or radio advertisements.

Identified barriers to IDA reduction strategies

Outer context

Limited resources at the individual, government and stakeholder levels led to supply chain barriers, which were further exacerbated by conflict and natural disasters undermining food security and community initiatives.35, 36 Inadequate supply of iron supplements in health facilities emerged as a common barrier for women accessing IDA care in LMICs.36-43 Unequal gender norms were also identified as an upstream barrier for women. Two studies highlighted how women's health and well-being ranked as the last priority in family dynamics after their children, husbands and in-laws.44, 45 Gender disparities extended to intrahousehold food allocation, influencing the quality and quantity of food women consumed. For instance, women were the ‘last to eat’ during meals and the remaining food was often not iron rich.36, 45, 46 In many households, women did not find it socially acceptable to prioritize health beyond pregnancy as there is a shift to focus on child health rather than maternal health.44 The expectation for women to complete household tasks was an identified challenge to engage meaningfully in IDA reduction strategies.44, 46 Furthermore, women's autonomy to leave the house for healthcare services and access communication technologies, such as mobile phones or computers, was reported to be limited.36, 45-47 Lastly, myths and misconstrued facts were described as significantly influencing iron supplement adherence. A common misperception illustrated in included studies was that iron supplements in pregnancy led to large-for-gestational age babies and therefore the associated complications of difficult labour or need for caesarean section.43, 44, 48, 49

Inner context

The HIV/AIDS epidemic was identified as barrier in both the outer and inner contexts, primarily in Africa. Women in these studies expressed concern that taking iron supplements would be misconstrued as taking anti-retroviral medications and as a result, they stopped taking iron supplements to avoid the associated stigmatization.50, 51 However, the concept of pill stigma was reiterated by studies in different geographical settings as a barrier to iron supplement uptake. Pill stigma was also rooted in the fundamental differences in approach to care between the biomedical model in Western countries and the traditional model in LMICs. This was substantiated by two studies reporting how iron supplements were viewed as medications and therefore associated with negative connotations.36, 52 Another identified barrier was the deprioritization of IDA in WRA. Women knew that iron supplements prevented anaemia but grossly underestimated the prevalence and risk of IDA, especially in non-pregnant women. This led to non-existent use and lack of distribution of iron supplements by health workers among this population.44, 45, 49 The impact of intergenerational influences was also described, with one study highlighting how ‘women have their own teachers’.51 Another study illustrated the significance of intrahousehold hierarchies where WRA held the lowest-ranking position below their in-laws.46 Mothers-in-law often discouraged WRA from taking iron supplements by perpetuating false myths with the reasoning that iron supplements were not available in their previous generations.44 Finally, the lack of information and communication technologies was reported to be a major barrier to health initiatives using telecommunication as a care delivery tool, especially in rural and remote settings.46, 47

Individual and innovation barriers

At the individual level, forgetfulness was cited as the most common barrier to iron supplement adherence.37, 51, 53-58 Having prior negative healthcare experiences and other medical comorbidities were also reported barriers.38, 43, 51 At the innovation level, four studies highlighted how non-adherence was attributed to ‘pill fatigue’, especially in patients with multiple comorbidities.43, 51, 53, 56 The gastrointestinal side effects of iron supplements, including nausea and constipation, were also another major deterrent, but guidance around expectations on side effects was key in ameliorating this.40, 54, 59-62

Identified facilitators of IDA reduction strategies

Outer context

Key identified facilitators included collaborative partnerships among international agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), national governments and local healthcare partners. These partnerships facilitated funding, staff support and capacity building.35, 63, 64 One study described how existing maternal and child health programmes were mobilized to expedite IDA reduction strategies.39 Another study highlighted how having a community-based approach and investing in community partnership was what contributed to programme sustainability.35 Moreover, the importance of having concrete monitoring and evaluation systems was underscored by multiple studies.35, 41, 64, 65 Monitoring and evaluation systems captured contextual and operational issues, allowing for further refinement of intervention delivery.35, 41, 64 These included conducting routine monitoring visits, reviewing compliance markers and ensuring information distribution to stakeholders.35, 65

Inner context

Three studies highlighted how peer educators, already part of an informal and naturally occurring social network, improved iron supplement adherence.35, 64, 66 Peers included respected community members as well as elders.64, 66 CHWs were also identified as an important link between health services and their community.42, 48, 65, 67 They provided care within the local cultural context and established trust with the community through longstanding relationships.41, 68 However, their effectiveness was noted to be highly dependent on having proper training and supportive supervision.68 CHW training included skill-building exercises on interpersonal communication using local terms and cultural factors related to IDA.59, 68 Furthermore, two studies described the potential role of female CHWs in providing IDA care as WRA were less comfortable with male CHWs conducting home visits.41, 59 Lastly, successful implementation strategies were found to utilize existing infrastructures, such as schools and antenatal clinics, to facilitate delivery of supplements and community initiatives.43, 58, 60-62, 69-71

Individual and innovation facilitators

Facilitators at the individual level included knowledge of anaemia and iron supplementation,55, 67, 72-76 partner support,53 high socioeconomic status36, 64, 66, 77 and maternal literacy.36, 67, 72, 74, 77, 78 Multiple studies highlighted that early access to antenatal care was also associated with iron supplement adherence.54, 73-79 Effective innovations implemented health education programmes in conjunction with iron supplement distribution. Counselling on IDA, possible benefits and side effects of iron supplements and ways to enhance iron absorption were found to improve compliance.37-39, 53, 61, 80, 81 Moreover, education initiatives that included women and their greater communities increased IDA knowledge. One study described how gender development workshops empowered women in community decision-making and increased women's control over food security.35 Community mobilization and the degree of community ownership also determined the success and sustainability of IDA reduction strategies.59, 64, 66 Three studies illustrated how mobilizing community and religious leaders in addition to health personnel built leadership support.35, 42, 61 Furthermore, taking a ‘healthy mothers, healthy babies’ approach to social marketing campaigns and highlighting how the baby's health is interdependent on the mother's well-being facilitated increased engagement with IDA reduction strategies. This is evidenced by two studies describing how the belief that iron supplements were associated with better foetal outcomes encouraged compliance.48, 51 Finally, adherence partners and peer mentoring programmes, commonly involving husbands, female relatives or children, were also reported to address social and cultural constraints tailored to the woman's individual context.50, 82

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first review of IDA reduction strategies and its implementation in the LMIC context. Guided by the intersectionality-enhanced CFIR and TDF frameworks, this scoping review highlighted an approach to Hemequity by identifying barriers and facilitators of IDA reduction strategies with implications for future public health interventions. The term Hemequity is derived from the name of a clinical research laboratory that aims to develop and foster an approach to equitable and inclusive care for patients with blood disorders.83 We found that the challenge of tackling IDA in LMICs lies in the disease's complex interactions with global poverty, gender inequity, sociocultural differences and other communicable diseases. Successful approaches were multifaceted, encompassing the key pillars of education, community ownership, gender empowerment and social advocacy.

Key contextual barriers included the under-prioritization of IDA risk in non-pregnant WRA. While LMICs continue to exhibit high rates of anaemia in non-pregnant women,84 many IDA reduction strategies have targeted only pregnant populations. This approach, unfortunately, promotes the detrimental effects of IDA throughout the female life cycle and interferes with more sustainable IDA prevention.13 Gender disparities and intergenerational influences were also identified as barriers to IDA interventions. Other studies have similarly noted how gender and social norms contribute to anaemia prevalence in LMICs by restricting access to preventative care and perpetuating gender disparities.85-87 This scoping review found that women's health ranked as the lowest priority in family dynamics, highlighting the need for public health efforts to prioritize the role of women in society. It also suggests a possible role for IDA reduction strategies that emphasize the interlinked nature of maternal and child health. The ‘healthy mothers, healthy babies’ approach has been successfully applied in other maternal health programmes to facilitate increased engagement.88 It is important to recognize that the intersection of younger age and sex for WRA place them in a particularly vulnerable position,45 and therefore implementation strategies that prioritize education and empowerment of women in community decision-making are key in tackling these barriers in a meaningful way throughout the entire female lifecycle. Education initiatives should include women and their surrounding communities, and be delivered by CHWs and peer educators, who provide counselling tailored to the local cultural context.

The concept of ‘pill stigma’ emerged as a salient theme in our study where women were fearful that taking iron supplements would be mistaken for taking anti-retroviral medications, suggesting additive stigma from the HIV/AIDS epidemic.50, 51 There are also high rates of anaemia in HIV/AIDS patients and iron deficiency is associated with increased mortality risk in this population.89, 90 This emphasizes how IDA reduction strategies cannot be established in isolation, and that infrastructures and resources from existing maternal health, communicable and non-communicable disease programmes should be incorporated into IDA reduction strategies. Pill stigma is also rooted in some of the fundamental differences between traditional, externalizing and biomedical, internalizing healthcare beliefs and models. Future interventions must integrate the two care models instead of viewing them as being mutually exclusive or divisive and recognize how the distinct concepts of health and disease are shaped by the surrounding cultural environment.91

Furthermore, the pervasive effects of poverty influencing supply chains, human-made conflicts and food insecurities highlight the social and moral responsibility for high-income countries to be engaged in tackling IDA as a global issue.35-43 Intersectoral collaboration with international agencies, NGOs, governments and local partners is essential in intervention implementation and health development.35, 63, 64 However, community mobilization and the degree of community ownership are fundamental to the success and sustainability of IDA reduction strategies.35, 41, 68 The WHO has similarly highlighted the importance of adopting community-based initiatives as a self-sustaining and people-oriented strategy to address diverse community needs in LMICs.92

The WHO's Global Nutrition Target calls for a 50% reduction in anaemia prevalence in WRA by 2025, however, the global prevalence of anaemia in WRA has remained stagnant since 2000.7, 93 Our study highlights the need to use intersectionality-enhanced implementation science frameworks with a clear understanding of robustly determined barriers and facilitators to develop IDA interventions and implementation strategies mapped to them.29, 30 Because these frameworks will be applied across diverse regions, successful interventions may look different in different geographical and political settings. Pragmatic studies are also needed to demonstrate how IDA reduction strategies can be disseminated in real-world settings, as present research has largely focused on intervention efficacy, rather than dissemination across systems.94 Moreover, future IDA reduction strategies must recognize IDA as a main driver of maternal death.95 Underlying causes such as heavy menstrual bleeding or gastrointestinal losses from helminth infections should be addressed.96 Lastly, limitations in infrastructure, trained personnel and local government funding have hindered researchers from conducting trials in LMICs.97 The lack of high-quality scientific evidence in iron replacement strategies and the under-representation of LMICs in IDA research are reflective of inherent structural sexism and racism, which further perpetuates health inequities in LMICs.97

Moving forward, future research must address methods of assessing IDA in resource-constrained settings to allow for early detection of IDA, especially given the higher prevalence of inherited red blood cell disorders in LMICs and uncertain risk of iron overload in those with severe disorders.5 Future IDA reduction strategies in the LMIC setting must be multifaceted, understanding that IDA is an outcome determined by social, political, environmental and nutritional variables. Future innovations should include the following components: (1) maternal health education involving women, communities and health personnel; (2) women's empowerment in community decision-making; (3) community ownership in the design and delivery of the intervention; (4) mobilization of existing resources with integration into existing communicable disease and maternal and child health programmes; and (5) feedback and reflexivity with strong monitoring and evaluation systems. Finally, anaemia is also one of many end-organ manifestations of iron deficiency and clinical and functional impairments that occur in the absence of anaemia.96, 98 Therefore, we must reframe iron deficiency in the absence of anaemia as a diagnosis that matters and as a condition that is worthy of treatment. Iron replacement remains the mainstay of treatment for iron deficiency. Reconceptualizing iron replacement as treatment and not just as ‘supplementation’ will raise the level of evidence required and therefore the scope of research being conducted in this realm.

The strengths of our study include the application of the intersectionality-enhanced versions of the TDF and CFIR frameworks. These frameworks provide a standardized way to conceptualize the impact of IDA reduction strategies within a complex global health landscape. This scoping review is also unique in that it focuses on intervention implementation and not only intervention effectiveness to provide guidance on how future IDA reduction strategies can actively engage with the LMIC context. Finally, our study expands on future directions and calls to action, highlighting the need for the prioritization of IDA, gender empowerment, community collaboration and knowledge translation interventions tailored to the LMIC context. One limitation of the study is that an assessment of methodological limitations or risk of bias was not performed in keeping with scoping review methodology. However, a rigorous protocol in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines was followed to reduce bias.23 Our study was limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English, which may have missed relevant non-English studies. We also excluded research articles studying the application of intravenous iron in the LMIC context given this is a complex topic that would warrant a separate scoping review. Furthermore, we could not exclude that included studies may be influenced by implicit bias and structural sexism. Lastly, there are limitations in geographical scope. Given most of the included studies were conducted in Africa and Southeast Asia, our findings may not be generalizable to all LMICs.

CONCLUSIONS

This scoping review identified numerous barriers and facilitators of IDA reduction strategies at different levels of the socio-ecological model and its interaction with individual-level factors. IDA is not only a medical problem but also one that is rooted in the sociocultural and political context. Both contextual and individual factors contribute to the overt and subclinical manifestations of IDA, leading to further iron debt, morbidity and mortality enabled by a backbone of structural sexism and racism in LMICs and high-income countries. This highlights the importance of using intersectionality-enhanced frameworks to develop sustainable IDA interventions and implementation strategies mapped to them. Future IDA reduction strategies must recognize the resilience of LMIC communities and acknowledge the importance of knowledge translation and exchange rooted within the local context with community ownership and empowerment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SG and MS conceptualized the study. SG, VH, MS and GHT designed the methods and analysis. SG, SA and VH collaborated on study searching, screening, data extraction and quality appraisal. All authors were involved in the interpretation and analysis of the data. CB was responsible for conceptualization and creation of included figures and diagrams. SG wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from MS and GHT. All authors critically reviewed the article for content and approved the final version. All authors had full access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the Hemequity Team at St. Michael's Hospital and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health for their support and mentorship in this project.

FUNDING INFORMATION

There was no specific funding source for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Sholzberg—Unrestricted research funding from Pfizer, Octapharma; honoraria from Pfizer, Octapharma, for advisory boards and speaking events.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

This study is a scoping review and does not involve human participants.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data relevant to the study are publicly available in the paper or online supplementary materials.