Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory immunoglobulin light chain (AL) amyloidosis: results from a large cohort of patients with long follow-up

Summary

Lenalidomide and dexamethasone (RD) is a standard treatment in relapsed/refractory immunoglobulin light chain (AL) amyloidosis (RRAL). We retrospectively investigated toxicity, efficacy and prognostic markers in 260 patients with RRAL. Patients received a median of two prior treatment lines (68% had been bortezomib-refractory; 33% had received high-dose melphalan). The median treatment duration was four cycles. The 3-month haematological response rate was 31% [very good haematological response (VGHR) in 18%]. The median follow-up was 56·5 months and the median overall survival (OS) and haematological event-free survival (haemEFS) were 32 and 9 months. The 2-year dialysis rate was 15%. VGHR resulted in better OS (62 vs. 26 months, P < 0·001). Cardiac progression predicted worse survival (22 vs. 40 months, P = 0·027), although N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) increase was frequently observed. Multivariable analysis identified these prognostic factors: NT-proBNP for OS [hazard ratio (HR) 1·71; P < 0·001]; gain 1q21 for haemEFS (HR 1·68, P = 0·014), with a trend for OS (HR 1·47, P = 0·084); difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains (dFLC) and light chain isotype for OS (HR 2·22, P < 0·001; HR 1·62, P = 0·016) and haemEFS (HR 1·88, P < 0·001; HR 1·59, P = 0·008). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (HR 0·71, P = 0·004) and 24-h proteinuria (HR 1·10, P = 0·004) were prognostic for renal survival. In conclusion, clonal and organ biomarkers at baseline identify patients with favourable outcome, while VGHR and cardiac progression define prognosis during RD treatment.

Introduction

Immunoglobulin light chain (AL) amyloidosis is caused by a misfolded light chain (LC) produced by a typically small plasma cell clone that leads to organ dysfunction both by deposition and direct proteotoxicity.1 Standard therapy is a chemotherapy targeting the B-cell clone and has the aim to induce a rapid and profound reduction of serum free LCs (FLC). Bortezomib-based regimens and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) in selected patients are the cornerstone of first-line therapy. Immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs) represent the backbone of rescue treatment.2, 3

Lenalidomide and dexamethasone (RD) is considered a standard treatment for relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis (RRAL). The effectiveness of this regimen was first documented in two small clinical trials, even though the maximum tolerated dose of lenalidomide was only 15 mg/day.4, 5 Later, three retrospective studies with <100 patients each have further confirmed the efficacy of RD as rescue treatment, with a haematological response in 41–61% of cases.6-8

However, treatment with RD is still a field of open issues like frequent haematological and non-haematological toxicities that often require dose reduction and treatment discontinuation. Nephrotoxicity8, 9 and increase of cardiac biomarkers [mainly N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)] represent further challenges in patient management.10 Finally, a deeper understanding of the impact of the cytogenetic status of the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia on outcome after RD is needed. Indeed, cytogenetic aberrations have emerged as another driver of prognosis in AL amyloidosis, especially according to treatment strategy.11-14

RRAL treatment is rapidly changing in AL amyloidosis, thanks to the introduction of novel powerful drugs (e.g. daratumumab and ixazomib) that may be used in combination with RD. Thus, a deep understanding of the impact of RD on the plasma cellular clone and on involved organs (mainly heart and kidney) is of utmost importance.

Methods

The database of the Heidelberg Amyloidosis Center was searched for patients with AL amyloidosis treated with RD. A total of 260 patients with RRAL were treated with RD between 01/06/2006 and 01/01/2020. All patients gave written informed consent for their data to be used in retrospective studies in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Diagnosis of AL amyloidosis was confirmed in all cases by Congo red staining on tissue biopsy and amyloid typing by immunohistochemistry.15 Diagnosis and severity of organ involvement were defined according to consensus criteria and validated staging systems.16-19 A cytogenetic evaluation by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation (iFISH) on bone marrow aspirate was available at baseline in 193 cases and was performed and defined as previously described (Supplementary Material).13, 20

Patients received lenalidomide (days 1–21) and dexamethasone (days 1, 8, 15 and 22) in 28-days cycles. Lenalidomide dose was adjusted according to clinical status and renal function. Every patient received thrombosis prophylaxis with acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg/day) or with low-molecular-weight heparin in case of history of thrombosis. Duration of treatment was decided according to treatment effectiveness and tolerability.

Haematological response was evaluated by intent-to-treat after every 3 months, according to current validated criteria 21, 22 and recent response criteria for patients with a difference of involved/uninvolved FLC (dFLC) between 20 and 50 mg/L.23, 24 A very good haematological response (VGHR) was defined as the achievement of a very good partial response (VGPR), complete response (CR) or low-dFLC partial response. Organ response and progression were assessed according to current validated criteria.19, 21

Replacement of missing data of European Mayo and renal stage based on expert knowledge was performed in 107 and 51 cases, respectively (Supplementary Material). Haematological event-free survival (haemEFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated as the time from RD initiation to the corresponding event of interest and plotted according to Kaplan–Meier. Differences in survival were tested for significance with the log-rank test. A haematological event was defined as haematological relapse or progression, change of treatment or death, as in previous published studies.11-13 Renal survival (RS) was calculated as time from diagnosis to dialysis initiation with death as competing event. Prognostic baseline factors for OS, haemEFS and RS were identified by multivariate (cause-specific) Cox hazard regression models and for VGHR by logistic regression analysis. Factors included in the model were age (as standard variable), LC isotype (to evaluate differences between λ and κ clones), dFLC, NT-proBNP and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and 24 h-proteinuria (important established prognostic biomarkers), t(11;14), gain 1q21 and high-risk cytogenetics (as relevant cytogenetic aberrations), starting dose of lenalidomide (to evaluate whether higher doses resulted in better outcome), previous ASCT (to assess the impact of the most effective treatment before RD) and year of RD initiation (to investigate possible changings in RD administration and/or availability of novel rescue treatments over time). Patients in dialysis were included for the identification of prognostic factors for OS, haemEFS and VGHR and were excluded for evaluation of RS. Statistical imputation has been performed for the covariates used in the multivariate models for the end-points OS, haemEFS and RS separately using multiple imputations by chained equations (Supplementary Material).25 Multivariable analysis was the focus of statistical analysis and the base for the study conclusions, while Kaplan–Meier plots were used to illustrate the results. Associations between categorical variables were tested using the chi-squared test, Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test for a difference in continuous variables. Calculations were performed using the statistical software environment R (version 4.0.1; R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), together with the R packages ‘survival’ (version 3.2-3), ‘mice’ (version 3·9.0) and ‘multcomp’ (version 1.4-13).

Results

A total of 260 patients with RRAL were treated with RD as rescue treatment (Table I). The median (range) time from diagnosis to treatment with RD was 17 (1–250) months. Patients received a median (range) of 2 (1–6) previous treatments, including ASCT in 87 (33%) cases. In all, 106 (41%) patients were bortezomib-refractory and 25 (10%) patients were already on dialysis at RD initiation. Translocation t(11;14) was observed in 103/193 (53%), gain 1q21 in 40/193 (21%) and high-risk cytogenetics in 17/193 (9%) cases respectively. The median (range) duration of RD was 4 (1–38) cycles and 18 (8%) patients received at least 12 cycles.

| Variable |

Relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis N°= 260 |

|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 163 (63) |

| Age, years, median (range) | 60 (34–79) |

| Intact monoclonal component, n (%) | 138 (53) |

| Monoclonal FLCs, n (%) | 122 (47) |

| Light chain isotype, n (%) | |

| κ | 60 (23) |

| λ | 200 (77) |

| Underlying clonal disease, n (%) | |

| MGCS | 69 (26) |

| SMM | 163 (63) |

| MM | 28 (11) |

| dFLC, mg/l, median (range) | 123 (1–8 665) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 13 (5) |

| dFLC >180 mg/l, n (%) | 90 (36) |

| Missing data | 13 (5) |

| dFLC <50 mg/l, n (%) | 51 (21) |

| Missing data | 13 (5) |

| Time to RD, months, median (range) | 17 (1–250) |

| Year of RD initiation, n (%) | |

| Before 01/01/2014 | 125 (48) |

| After 01/01/2014 | 135 (52) |

| Previous treatment lines, n, median (range) | 2 (1–6) |

| Pre-treatment strategies, n (%) | |

| Bortezomib | 177 (68) |

| ASCT | 87 (33) |

| IMiDs | 18 (7) |

| Refractory to bortezomib, n (%) | 106 (41) |

| Lenalidomide starting dose, mg/day, median (range) | 15 (5–25) |

| Lenalidomide 25 mg/day, n (%) | 17 (7) |

| Lenalidomide 15 mg/day, n (%) | 136 (55) |

| Lenalidomide 10 mg/day, n (%) | 66 (27) |

| Lenalidomide 5 mg/day, n (%) | 29 (12) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 12 (5) |

| Dexamethasone starting dose, mg, median (range) | 20 (4–40) |

| Dexamethasone 40 mg, n (%) | 6 (3) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 44 (17) |

| Number of cycles, median (range) | 4 (1–38) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 26 (10) |

| Organ involvement, n (%) | |

| Heart | 182 (70) |

| Kidney | 144 (55) |

| Liver | 42 (16) |

| Soft tissues | 108 (42) |

| PNS | 56 (22) |

| ANS | 47 (18) |

| Number of involved organs, n (%) | |

| 1 | 56 (22) |

| 2 | 82 (32) |

| ≥3 | 122 (47) |

| NT-proBNP, ng/l, median (range) | 1746 (20–386 453) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 34 (13) |

| NT-proBNP >8500 ng/l, n (%) | 39 (17) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 34 (13) |

| Mayo staging*, n (%) | |

| I | 35 (21) |

| II | 60 (36) |

| IIIa | 52 (31) |

| IIIb | 21 (13) |

| Missing data | 92 (35) |

| Proteinuria, g/24-h, median (range)† | 1·57 (0 01–30 3) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 70 (27) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1·73 m2, median (range)‡ | 70 (13–127) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 19 (7) |

| eGFR <50 mL/min/1·73 m2, n (%) | 46 (18) |

| Renal staging||, n (%) | |

| I | 138 (64) |

| II | 57 (27) |

| III | 19 (9) |

| Missing data | 46 (18) |

| Dialysis at RD initiation, n (%) | 25 (10) |

| iFISH, n (%) | 193 (74) |

| t(11;14) , n (%) | 103 (53) |

| gain 1q21°, n (%) | 40 (21) |

| High risk¶, n (%) | 17 (9) |

| Hyperdiploidy, n (%) | 33 (13) |

| del8p21, n (%) | 7 (4) |

- ANS, autonomic nervous system; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; dFLC, difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FLCs, free light chains; iFISH, interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation; IMiDs, immunomodulatory imide drugs; MGCS, monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance; MM, multiple myeloma; SMM, smouldering multiple myeloma; RD, lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

- Unless otherwise specified, data were reported as N (%).

- * Mayo staging was imputed in 107 patients with relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis. According to non-imputed data 10 patients were in Stage I, 23 in Stage II, 19 in Stage IIIa and nine in Stage IIIb.

- † 24-h proteinuria was not available in 25 patients in dialysis at RD initiation due to anuria.

- ‡ Patients in dialysis at RD initiation were not considered for the evaluation of median eGFR.

- || Renal staging was imputed in 51 with relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis. According to non-imputed data 99 patients were in Stage I, 49 in Stage II and 15 in Stage III. Patients in dialysis at RD initiation were not evaluable for renal staging.

- ° In two of these cases 1q21 amplification was observed.

- ¶ High-risk cytogenetics was defined as either presence of del17, t(4;14) or t(14;16).

Adverse events were observed in 198/260 (76%) patients and resulted in treatment discontinuation in 57 (22%) and lenalidomide dose reduction in 42 (16%) cases (Table II).

| Adverse events | Any grade | Grade 3–4 |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Cytopenia | 101 (39) | 21 (8) |

| Lymphocytopenia | 34 (13) | 4 (1) |

| Neutropenia | 27 (10) | 8 (3) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 20 (8) | 2 (1) |

| Anaemia | 11 (4) | 5 (2) |

| Leucopenia | 5 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Pancytopenia | 4 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Infections | 77 (30) | 18 (7) |

| Infections NOS | 28 (11) | 2 (1) |

| Lung infections | 15 (6) | 4 (1) |

| Airways infections | 10 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal infections | 5 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Soft tissues infections | 5 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Urinary tract infections | 5 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Sepsis | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Otitis | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Meningitis | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Endocarditis | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Sinusitis | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| GI toxicity | 57 (22) | 1 (<1) |

| Diarrhoea | 28 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Constipation | 17 (7) | 1 (<1) |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Dyspepsia | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Duodenal ulceration | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Cardiac toxicity | 54 (21) | 34 (12) |

| Heart failure | 31 (12) | 17 (7) |

| Hypotension | 17 (7) | 13 (5) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 6 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Renal toxicity | 26 (10) | 15 (6) |

| Acute kidney injury | 6 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Chronic kidney failure | 20 (8) | 9 (3) |

| Skin and mucosal toxicity | 23 (9) | 4 (1) |

| Skin rash | 21 () | 4 (1) |

| Mucositis | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Dexamethasone toxicity | 15 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Insomnia | 9 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Poor tolerability | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Hiccups | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Hoarseness | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Palpitations | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| CNS and PNS toxicity | 26 (10) | 6 (2) |

| Dizziness | 10 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Polyneuropathy | 9 (3) | 1 (<1) |

| Depression | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Seizures | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Optic nerve neuritis | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Encephalopathy | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Thromboembolic event | 8 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Superficial venous thrombosis | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Atrial thrombosis | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Ictus | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Bleeding | 12 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Bleeding NOS | 5 (2) | 0 (0) |

| GI bleeding | 4 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Conjunctival bleeding | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Periorbital bleeding | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Skin bleeding | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

- CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; NOS, not otherwise specified; PNS, peripheral nervous system; RD, lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

- Total numbers for each adverse event category given in bold.

Survival, haematological response and organ progression

After a median follow-up of 56·5 months, 229 (88%) had a progression-defining event (Supplementary Material) and 167 (64%) had died. The median haemEFS and OS were 9 and 32 months respectively. In all, 31 (12%) patients progressed to end-stage renal failure requiring dialysis. Rate of progression to dialysis at 1 and 2 years from RD initiation was 9% and 15% respectively. Six patients in renal Stage I (all with kidney involvement) progressed to dialysis after a median (range) of 12 (1–17) months.

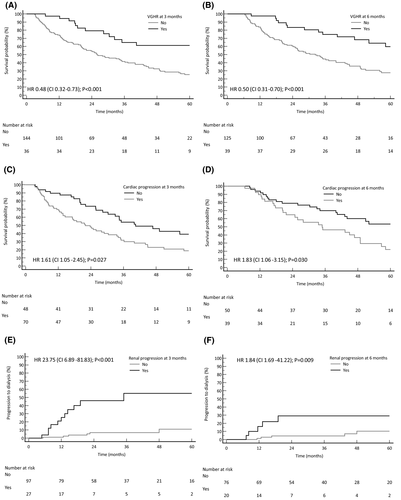

Haematological response rate (HRR) at 3 and 6 months are reported in Table III. The 3-month landmark analysis showed that achieving a 3-month VGHR resulted in better OS (62 vs. 26 months, P < 0·001; Fig 1A). A benefit in OS was also seen in those who achieved a 6-month VGHR (Fig 1B).

| Response, n (%) | Response at 3 months | Response at 6 months |

|---|---|---|

| N°= 197 | N =201 | |

| Any haematological response | 62 (31) | 62 (31) |

| VGHR | 36 (18) | 40 (20) |

| CR | 8 (4) | 11 (5) |

| VGPR | 25 (12) | 29 (15) |

| Low-dFLC PR* | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| PR | 26 (13) | 22 (11) |

- CR, complete response; dFLC, difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains; PR, partial response; VGHR very good hematologic response; VGPR, very good partial response. Of these:

- * 22 patients evaluable for response at 3 months had a dFLC between 20 and 50 mg/l before starting RD: three achieved a low-dFLC PR and one a CR. Among those evaluable for response at 6 months, 23 had a dFLC at RD initiation between 20 and 50 mg/l: only one patient achieved a CR.

In 101/122 (83%) evaluable patients NT-proBNP increased after 3 months of RD, both with and without cardiac amyloidosis (Supplementary Material). The current NT-proBNP-based cardiac progression criteria21 were reached in 73/122 (60%) cases and resulted in worse OS (22 vs. 40 months, P = 0·027; Fig 1C). Similar results were seen when cardiac progression occurred at 6 months [40/90 (44%) cases; Fig 1D].

A worsening in eGFR was observed in 90/131 (69%) evaluable subjects after 3 months of therapy, regardless of whether renal amyloidosis was present or not. A decrease in eGFR of >25%, as per current renal progression criteria, was observed in 30/131 (23%) cases and resulted in shorter RS (35 months vs. not reached, P < 0·001; Fig 1E). Renal progression at 6 months also resulted in poorer RS [22/99 (22%) cases; Fig 1F].

Identification of prognostic factors

Exploratory and unadjusted results of univariable analysis are reported in Table SI.

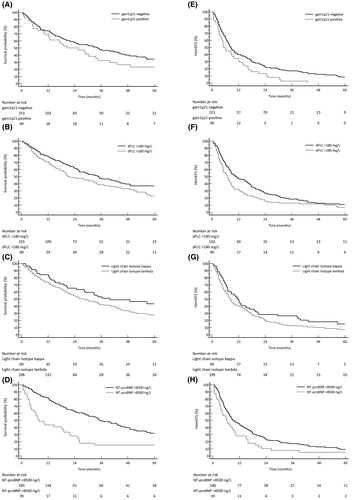

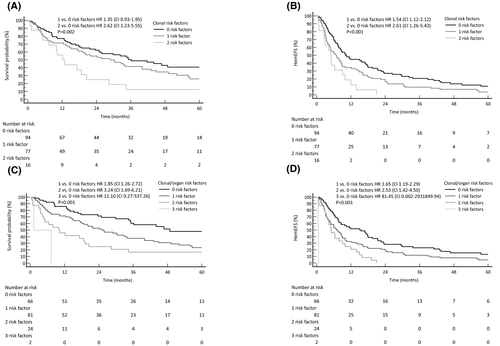

Multivariable analysis with statistical imputation for OS and haemEFS is shown in Table IV (complete case analysis in Table SII). Gain 1q21 was a negative prognostic factor for haemEFS [hazard ratio (HR) 1·68, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1·12–2·53, P = 0·014], along with high dFLC(log10) (HR 1·88, 95% CI 1·47–2·39, P < 0·001) and LC λ isotype (HR 1·59, 95% CI 1·14–2·23, P = 0·008). Gain 1q21 was the only cytogenetic aberration with a trend to statistical significance for an effect on OS (HR 1·47, 95% CI 0·95–2·28, P = 0·084). Other predictors of OS were high dFLC(log10) (HR 2·22, 95% CI 1 62–3 03, P < 0 001), LC λ isotype (HR 1 62, 95% CI 1 10–2 39, P = 0 016) and high NT-proBNP(log10) (HR 1 71, 95% CI 1 27–2 31, P < 0 001). Year of RD initiation was associated with a benefit in OS (HR 0 94, 95% CI 0·89–0·99, P = 0 014), but slightly worse haemEFS (HR 1 06, 95% CI 1 01–1 11, P = 0 012). These results are partially illustrated by Kaplan–Meier plots in Fig 2. Combination of 1q status and dFLC at treatment initiation (cut-off: 180 mg/l) identified patients who could benefit more from RD (Fig 3A,B). Adding NT-proBNP (cut-off: 8500 ng/l) to these two clonal risk factors also helped in the discrimination of patients with good or dismal prognosis (Fig 3C,D).

| Variable | OS, n = 260 | haemEFS, n = 260 | VGHR, n = 132 | RS, n = 235 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age at RD, years* | 1 03 | 0 86–1 25 | 0 716 | 0 96 | 0 82–1 13 | 0 632 | 0 97 | 0 92–1 03 | 0 339 | 1 02 | 0 98–1 06 | 0 4 |

|

Light chain isotype λ vs. κ |

1 62 | 1 10–2 39 | 0 016 | 1 59 | 1 13–2 24 | 0 008 | 1 36 | 0 37–6 13 | 0 666 | 1 01 | 0 39–2 62 | 0 991 |

| dFLC (log10), mg/l | 2 22 | 1 62–3 03 | <0 001 | 1 88 | 1 47–2 39 | <0 001 | 0 11 | 0 02–0 40 | 0 002 | 1 2 | 0 65–2 23 | 0 568 |

| t(11;14), yes | 0 91 | 0 61–1 35 | 0 717 | 0 89 | 0 63–1 27 | 0 528 | 4 78 | 1 42–19 50 | 0 017 | – | – | – |

| Gain 1q21, yes | 1 47 | 0 95–2 28 | 0 084 | 1 68 | 1 11–2 53 | 0 014 | 0 7 | 0 15–2 72 | 0 62 | – | – | – |

| High risk iFISH, yes | 0 8 | 0 42–1 53 | 0 501 | 0 69 | 0 39–1 20 | 0 188 | 6 4 | 1 13–39·29 | 0·037 | – | – | – |

| NT-proBNP (log10), ng/l | 1 71 | 1 27–2 31 | <0 001 | 1 17 | 0 92–1 49 | 0 194 | 0 84 | 0 38–1 82 | 0 649 | 1 73 | 0 83–3 59 | 0 159 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1·73 m2† | 1 | 0 99–1 01 | 0 903 | 0 98 | 0 92–1 04 | 0 449 | 1 01 | 0 99–1 03 | 0 504 | 0 71 | 0 57–0 88 | 0 004 |

| Proteinuria, g/24 h | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 1 | 1 04–1 16 | 0 004 |

| Starting dose of lenalidomide, mg/day | 0 89 | 0 72–1 01 | 0 281 | 0 93 | 0 77–1 44 | 0 461 | 1 09 | 0 94–1 27 | 0 256 | 1 04 | 0 94–1 15 | 0 469 |

| Pre-treatment with ASCT, yes | 0 85 | 0 59–1 24 | 0 407 | 1 05 | 0 76–1 44 | 0 77 | 1 28 | 0 40–4 12 | 0 674 | – | – | – |

| Year of RD initiation | 0 94 | 0 89–0 99 | 0 014 | 1 06 | 1 01–1 11 | 0 012 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

- ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CI, confidence interval; dFLC, difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; haemEFS, haematological event-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; iFISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation; OR, odds ratio; OS, overall survival; RD, lenalidomide and dexamethasone; RRAL, relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis; RS, renal survival; VGHR, very good haematological response.

- Multivariable complete case analysis was used for 3-month VGHR, while statistical imputation was performed for OS, haemEFS and RS. Number of events was 166 for OS, 229 for haemEFS and 56 for RS. A lower number of analysed covariates had to be chosen for RS due to the lower number of events.

- * Impact reported for 10 years change.

- † Impact reported for change of 10/mL/min/1·73 m2.

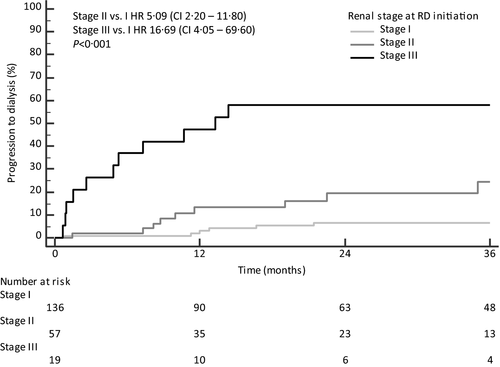

Multivariable analysis with statistical imputation for predictors of RS was also performed, adjusting eGFR and 24-h proteinuria for starting dose of lenalidomide, NT-proBNP and dFLC concentration (Table IV). This analysis revealed higher proteinuria (HR 1·10, 95% CI 1·03–1·16, P = 0 004) and lower eGFR (HR 0·71, 95% CI 0·57–0·88, P = 0·004) as the only statistically significant prognostic factors for RS (for complete case analysis see Table SII). When proteinuria and eGFR were combined in the validated renal staging system at RD initiation, three different groups of patients with significantly different risk of progression to dialysis were identified (Fig 4).

Complete case multivariable analysis was performed for 3-month VGHR. The 3-month VGHR was predicted by dFLC(log10) [odds ratio (OR) 0·11, 95% CI 0·02–0·40, P = 0 002]. Interestingly, harbouring high risk cytogenetics or t(11;14) was associated with higher chances of achieving VGHR at 3 months (Table IV).

Discussion

With 260 patients, we present the largest series of RD in RRAL with a long follow-up and cytogenetic data in >70% of cases. Our aim was the assessment outcome after RD and the identification of prognostic factors with a clonal and organ biomarker-based approach.

Haematological response and survival in comparison with other studies

Our present 3-months HRR by intent-to-treat was lower (31%) than reported in other studies. This was particularly evident when compared to the HRR of 61% observed by the London group in 84 patients with RRAL, which showed also unprecedently long OS (median not reached) and progression-free survival (median 44·5 months).7 These differences could be best explained with differences in patient populations. In our present study, heart involvement was more frequent and NT-proBNP and dFLC were higher at treatment initiation (Table V).4, 5 This seems to be a striking difference with a big impact on patient’s outcome, as higher NT-proBNP emerged in our present study as a negative prognostic factor for OS, while higher dFLC was a strong predictor of shorter OS and haemEFS and lower 3-month VGHR rates. Moreover, the lenalidomide dose was 25 mg/day in 54% of cases in the London series, providing a further indication of a very fit population of patients. Recently, a pooled analysis of three clinical trials evaluating effectiveness of IMiDs (lenalidomide and pomalidomide) in AL amyloidosis, showed an HRR and a median OS in RRAL of 39% and 36 months respectively.26 These data are comparable to those observed in our present series and we think they accurately describe the impact of IMiDs in a representative population of RRAL. However, even if deep haematological responses were not frequent (3-month VGHR 18%), they still resulted in long OS (>5 years). Previous treatment history did not affect outcome and HRR, while dialysis at RD initiation did not have a significant impact on haematological response, but resulted in worse OS, highlighting the frailty of this patient group (Table SII). In recent years, novel effective therapies have become available in RRAL, allowing rescue of patients relapsed after RD and to treat earlier those who did not achieve a satisfactory response. This probably explains the effect of year of RD initiation on outcome observed on multivariable analysis.

| Variables | Dispenzieri et al. 2007 [4] | Sanchorawala et al. 2007 [5] | Palladini et al. 2012 [6] | Mahmood et al. 2014 [7] | Kastritis et al. 2018 [8] | Present study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Phase II | Phase II | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective |

| Follow-up, months, median | 17 | n.a. | 23 | 21 | 28 | 56·5 |

| Number of patients | 23 | 34 | 24 | 84 | 55 | 260 |

| Treatment-naïve, n | 10 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| Relapsed/refractory, n | 13 | 31 | 24 | 84 | 55 | 260 |

| Age, years, median (range) | 62 (44–88) | 65 (44–84) | 59 (42–72) | 64 (45–79) | 63 (48–82) | 60 (34–79) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 14 (59) | 24 (71) | 16 (67) | 43 (51) | 36 (65) | 163 (63) |

| Cardiac, n (%) | 14 (64) | 13 (38) | 16 (67) | 42 (50) | 40 (72) | 182 (70) |

| Renal, n (%) | 16 (73) | n.a. | 18 (75) | 52 (62) | 41 (75) | 144 (55) |

| >2 organs, n (%) | n.a. | 7 (21) | n.a. | 36 (43) | n.a. | 122 (47) |

| Dose of lenalidomide, mg |

25 (starting dose) |

25 (starting dose) |

15 (max. dose) |

25 (in 54% of cases) |

10 (median) |

15 (median) |

| Dose reduction, % | 26 | Study dose reduced to 15 mg | n.a. | 16 | 60 | 16 |

| Previous lines of treatment, median (range) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–5) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–6) | 1 (1–4) | 2 (1–6) |

| ASCT, n (%) | 6 (27) | 19 (56) | 7 (29) | 13 (15) | 7 (13) | 87 (33) |

| Bortezomib, n (%) | n.a. | 7 (21) | 24 (100) | 58 (69) | 40 (73) | 177 (68) |

| IMiDs, n (%) | n.a. | n.a. | 11 (45) | 64 (76) | 2 (4) | 18 (7) |

| Haematological response, % | 41 | 67 | 41 | 61 | 51 | 31 |

| VGPR, % | n.a. | n.a. | – | 20 | 5·50 | 14 |

| CR, % | n.a. | 29% | – | 8 | 20 | 4 |

| Median OS, months | n.a. | n.a. | 14 | not reached | 25 | 32 |

| Median PFS, months | 18·8 | n.a. | n.a. | 44·5 | n.a. | 9 |

| Negative prognostic factors at start of therapy for OS | n.a. | n.a. |

cTnI >0 1 ng/ml Time to RD <18 months |

NT-proBNP >8500 ng/l |

Exposure to bortezomib Mayo Stage III |

dFLC gain 1q21 LC isotype NT-proBNP |

- ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CR, complete remission; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; IMiDs, immunomodulatory imide drugs; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RD, lenalidomide and dexamethasone; RRAL, relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis; VGPR, very good partial response.

Toxicity, renal and cardiac failure or progression

Treatment with RD was characterised by frequent toxicity (76% of patients; haematological toxicity in 39% of cases). The most frequent non-haematological toxicities were infectious complications (30% of cases; Grade 3–4 in 7%). Renal toxicity occurred in 25 patients and was severe in 15. Worsening of renal function during RD was more frequent in patients with renal involvement and high proteinuria.8, 9 We observed that 24-h proteinuria and eGFR were the only statistically significant prognostic factors for RS. Moreover, we confirmed that the current validated renal staging system for AL amyloidosis 19 is capable of identifying patients with worse RS also in RRAL. Importantly, progression to dialysis occurred also in Renal Stage I, even if rarely. Finally, patients in whom eGFR worsened >25% after 3 months of treatment had a higher progression to dialysis. For this reason, lenalidomide should be avoided in cases of intermediate-advanced renal amyloidosis and a careful monitoring of creatinine should be performed during RD treatment.

NT-proBNP at RD initiation was confirmed as powerful predictor of OS.7, 8 However, follow-up with this cardiac biomarker is hampered by the frequent increase of its concentration during treatment with IMiDs.10 We observed a median increase of NT-proBNP of >1 500 ng/l and >90% in 83% of patients at 3 months and >1 200 ng/l and >100% in 74% of cases at 6 months (Supplementary Material). However, cardiac progression at 3 and 6 months after RD initiation resulted in shorter OS. Therefore, signs of early cardiac progression should be evaluated carefully and are clinically meaningful.

The impact of iFISH aberrations and other clonal markers on treatment

With the continuous improvement of patient survival,27 clonal biomarkers emerged as important prognostic factors for long-term survival and progression in AL amyloidosis.28, 29 We identified three clonal prognostic factors in patients with RRAL treated with RD. Higher dFLC at RD initiation resulted in worse survival. Cytogenetics is an emerging field in AL amyloidosis and it has been proposed to introduce iFISH abnormalities into the risk-adapted treatment strategy.1, 30 However, only limited and not conclusive data on the role of iFISH abnormalities in patients with AL amyloidosis exposed to lenalidomide are available.14, 31 In the present study, we show for the first time that gain 1q21 resulted in significantly shorter haemEFS with a trend for worse OS in RRAL treated with RD, even when the analysis was adjusted for dFLC, severity of cardiac involvement and treatment history. The adverse prognostic role of gain 1q21 was already described in patients with multiple myeloma (MM) treated with RD.32 In AL amyloidosis, gain 1q21 was a marker of worse outcome in patients treated with oral melphalan and dexamethasone 11 and, more recently, daratumumab.33 Translocation (11;14) was not associated with better survival, although these patients were more likely to achieve VGHR after 3 months of treatment. The same observation was made in patients with high-risk iFISH. Finally, LC isotype emerged as another clonal prognostic factor for both OS and haemEFS, probably due to differences in organ involvement, clonal and amyloidogenic features (Table SIII).34, 35

Possible implications of our findings on treatment of AL amyloidosis

Lenalidomide and dexamethasone is one of the most commonly rescue regimens in AL amyloidosis.36Our present study adds valuable information on the risk assessment and management of patients with RRAL treated with this regimen. Clonal and organ biomarkers identified patients with different outcome to RD. Patients with dFLC >180 mg/l and gain 1q21 had a very short haemEFS and OS, when compared with those with one or none of these risk factors. This was further noticed when severity of cardiac involvement (NT-proBNP 8 500 ng/l) was considered along with clonal risk factors. The role of lenalidomide in AL amyloidosis is animatedly discussed, especially after the advent of novel and powerful drugs. A phase III trial showed that ixazomib and dexamethasone (ID) was superior to other rescue treatments (RD in 57% of cases) in preserving vital organ function in RRAL.37 Adding lenalidomide to ID (IRD) resulted in a powerful oral triplet for RRAL in a recent retrospective study (HRR 59% and VGHR 41%).38, 39 IRD is already an effective treatment option in MM.40 Daratumumab, an anti-cluster of differentiation 38 (CD38)+ monoclonal antibody, RD (DRD) is an effective treatment in relapsed/refractory MM.41 One rationale of this combination is the synergic activity of lenalidomide, enhancing the expression of CD38 on the cellular membrane of MM plasma cells.42 Daratumumab is effective in RRAL,33, 43-45 but only few data are available on the DRD combination. Recently, our group reported high HRR (with ≥VGHR in 65%) and long-lasting responses (median haemEFS 17·3 months) to DRD in RRAL.46 Interestingly, gain 1q21 resulted again in shorter haemEFS and lower VHGR rate. Lastly, preliminary results about the effectiveness of elotuzumab, an anti-signalling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 7 antibody, lenalidomide and dexamethasone were observed in AL amyloidosis.47

The better HRR and VGHR rates make lenalidomide combinations, especially those with proteasome inhibitors and daratumumab, particularly appealing. However, triple regimens are characterised by increased treatment-related toxicity and mortality, especially in frail patients with AL amyloidosis.31, 48

Study limitations

The present study has some limitations related to its retrospective nature. Cytogenetic data were not available in all cases and was performed mostly at diagnosis, resulting in a possible underestimation of prevalence of gain 1q21.49 However, the present series is the largest reporting cytogenetic data in RRAL. Mayo clinic re-staging at RD initiation was not possible in all cases. Finally, treatment tolerability of treatment could have been slightly overestimated, due to the lack of a prospective recording of adverse events.

Conclusion

Our study presents novel data resulting in a refinement in our way to manage treatment with lenalidomide in patients with RRAL, suggesting the possibility of a biomarker-based approach. Clonal and organ biomarkers (1q21 status, dFLC, LC isotype and NT-proBNP) identified patients that benefit more from treatment with RD. Cardiac and renal biomarkers distinguish patients more fragile at treatment initiation, in whom treatment with lenalidomide should be considered with caution and detect early organ progression. This is particularly important as the promising data of triple combination therapies like IRD and DRD will increase efficacy and result in a novel and wider role of lenalidomide in treatment of AL amyloidosis.

Conflict of interest

Marco Basset: honoraria from Janssen. Hartmut Goldschmidt: honoraria, grants and/or provision of Investigational Medicinal Product and research funding from and membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees of Amgen, BMS, Celgene and Janssen; honoraria, research funding from and membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees of Sanofi; honoraria and research funding from Novartis; research funding from and membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees of Takeda; honoraria, grants and/or provision of Investigational Medicinal Product and research funding from Chugai; grants and/or provision of Investigational Medicinal Product from John Hopkins University; research finding from Incyte, Molecular Partners, Merck Sharp and Dohme and Mundipharma; honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline; membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees of Adaptive Biotechnology. Carsten Müller-Tidow: research funding from and membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees of Pfizer; membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees of Janssen-Cilag; research funding from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, BMBF, Wilhelm-Sander-Stiftung, Jose-Carreras-Siftung and Bayer AG. Ute Hegenbart : honoraria and travel support to meetings from and membership on the advisory Board of Janssen; travel support to meetings from and membership on the advisory Board of Prothena; honoraria from and membership on the advisory Board of Pfizer; honoraria from Alnylam, and Akcea. Stefan O. Schönland: honoraria, travel support to meetings and research funding from Janssen, Prothena and Takeda.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Marco Basset, Ute Hegenbart and Stefan O. Schönland. Provision of study material or patients: Marco Basset, Christoph R. Kimmich, Tobias Dittrich, Kaya Veelken, Hartmut Goldschmidt, Anja Seckinger, Dirk Hose, Anna Jauch, Carsten Müller-Tidow, Ute Hegenbart, and Stefan O. Schönland. Collection and assembly of data: Marco Basset, Christoph R. Kimmich, Nicholas Schreck, Julia Krzykalla, Axel Benner, Ute Hegenbart, and Stefan O. Schönland. Data analysis and interpretation: Marco Basset, Christoph R. Kimmich, Nicholas Schreck, Julia Krzykalla, Tobias Dittrich, Kaya Veelken, Hartmut Goldschmidt, Anja Seckinger, Dirk Hose, Anna Jauch, Carsten Müller-Tidow, Axel Benner, Ute Hegenbart, and Stefan O. Schönland. Writing the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: all authors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our patients and their families, local haematologists, general practitioners and our hospital staff for their participation in this study. This study was in part funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Research Unit FOR 2969, projects HE 8472/1-1, SCHO 1364/2-1).