Correspondence in reference to the previously published Epub manuscript: immune thrombocytopenic purpura after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

We read with great interest the correspondence published recently by Candelli et al.1 The authors describe the possible first case of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) subsequent to an injection of ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccine. The latter is based on a chimpanzee adenovirus vaccine vector that has been modified to contain the genetic information needed to reproduce SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins. The authors consider the chronology and, after having excluded several alternative etiologies, retain the diagnosis of ITP induced by vaccination. They rightly specify that they cannot completely rule out the possibility of a random temporal association between the onset of primary ITP and vaccination. However, we believe there are two further possible causes of ITP that could be considered or discussed.

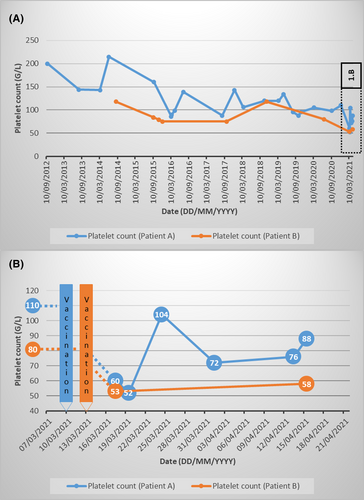

Our first hypothesis is that the patient described by Candelli et al. may have already had primary immune thrombocytopenia before vaccination. Any mild and asymptomatic form of immune thrombocytopenia prior to vaccination could have remained undetected. The authors agree that the concomitant detection of a lupus anticoagulant and ITP could indicate a pre-existing autoimmune disorder, as lupus anticoagulant is closely associated with primary immune thrombocytopenia.2 The authors’ observation that the patient had no medical history is not discordant, as this healthy 28-year-old man had previously had no medical reason to check his platelet count. Vaccination would therefore be an aggravating factor. It is not uncommon to observe transient drops in platelet counts post vaccination for patients with ITP and other causes of thrombocytopenia.4 We can illustrate this with two recent cases. Two women with primary immune thrombocytopenia presented a transient or moderate worsening of their thrombocytopenia after vaccination by ChAdOx1 nCov-19 (data not published). The first woman (A) was 62 years old and had been diagnosed with asymptomatic thrombocytopenia eight years earlier. She was overweight and had dyslipidaemia and hypertension. The second woman (B) was 45 years old. She had no medical history other than a known asymptomatic primary immune thrombocytopenia diagnosed seven years earlier. The kinetics of their platelet counts are shown in Fig 1. Questioning, clinical examination and biological controls (especially immunological and infectious) did not reveal any other factors that could exacerbate thrombocytopenia. These patients reported a very brief and moderate influenza-like syndrome (without fever) 48 h after vaccination. Unlike the case of Candelli et al., our patients did not have purpura or haemorrhagic syndrome. No treatment was necessary.

Alternatively, another adverse effect of the vaccine could have played a role for the patient of Candelli et al.1 In recent weeks, several cases of unusual thrombocytopenia and thrombotic events have been described after vaccination with ChAdOx1 nCov-19.3, 5 A novel underlying mechanism associated with these complications is in the process of being identified. A pathogenic PF4-dependent syndrome, unrelated to the use of heparin therapy, can occur after the administration of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine.6 In the cohort studied by Scully et al. to identify this mechanism, one patient (case 14) had severe acute thrombocytopenia (14 days after vaccination) associated with elevated D-dimer levels (admittedly much higher than the patient of Candelli et al.) and bleeding symptoms only, without thrombosis. PF4-IgG testing was positive. The absence of thrombosis does not therefore rule out this diagnosis. Moreover, when considered in the light of the algorithm suggested by Scully et al., the case report of Candelli et al. is located in the ambiguous zone (acute isolated thrombocytopenia, D-dimer levels between 2 000 and 4 000 IU/l, low or normal fibrinogen). In this clinical situation of ITP occurring 5–30 days after a ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination, it could therefore be interesting to carry out biological explorations for the detection of pathological anti-PF4 antibodies.

Additional investigation is needed to determine the incidence and the etiologies of thrombocytopenia post vaccination. In our opinion, the benefit-risk balance remains in favour of vaccination for patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. A systematic control of platelet count seven days after vaccination could be proposed.

Funding information

No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this manuscript.

Author contributions

QS and LT designed the paper. QS wrote the first draft of the paper with input from ML, ÉH and LT. All the authors revised the manuscript and approved the final form.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient consent statement

The patients had been informed beforehand in their letters of consultation that unless they expressed an objection, their medical data could be used in an anonymous form for medical publications. No objections were expressed by any of the included patients.