Real-world tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment pathways, monitoring patterns and responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in the United Kingdom: the UK TARGET CML study

The copyright line for this article was changed on 16 June 2020 after original online publication.

Summary

Management of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) has recently undergone dramatic changes, prompting the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) to issue recommendations in 2013; however, it remains unclear whether real-world CML management is consistent with these goals. We report results of UK TARGET CML, a retrospective observational study of 257 patients with chronic-phase CML who had been prescribed a first-line TKI between 2013 and 2017, most of whom received first-line imatinib (n = 203). Although 44% of patients required ≥1 change of TKI, these real-world data revealed that molecular assessments were frequently missed, 23% of patients with ELN-defined treatment failure did not switch TKI, and kinase domain mutation analysis was performed in only 49% of patients who switched TKI for resistance. Major molecular response (MMR; BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·1%) and deep molecular response (DMR; BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·01%) were observed in 50% and 29%, respectively, of patients treated with first-line imatinib, and 63% and 54%, respectively, receiving a second-generation TKI first line. MMR and DMR were also observed in 77% and 44% of evaluable patients with ≥13 months follow-up, receiving a second-generation TKI second line. We found little evidence that cardiovascular risk factors were considered during TKI management. These findings highlight key areas for improvement in providing optimal care to patients with CML.

Introduction

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have revolutionised outcomes for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in chronic phase (CML-CP), with survival rates approaching those of the general population.1-3 Consequently, key considerations for optimal patient care have evolved considerably. While the primary aim remains achievement of molecular response that minimises the risk of disease progression,4 it is increasingly evident that complications of the treatment need to be considered. It is therefore essential for physicians to understand the best use of the available ABL1-targeting TKIs.4 This is the principal purpose of the 2013 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommendations, which increased focus on molecular responses at three, six and 12 months, with patients' responses categorised as optimal, warning or failure.4 Patients experiencing failure are at particular risk of disease progression, and the guidelines recommend that such patients switch treatment and undergo assessment for BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutations.4

While the ELN 2013 guidelines state that patients must achieve a major molecular response [MMR; BCR-ABL1 ≤0·1% on the International Scale (IS)] by 12 months for their response to be considered optimal,4 deeper levels of response, including MR4 (BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·01%) and MR4·5 (BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·0032%), are also recognised as important milestones.5-7 Some patients with a sustained deep molecular response (DMR, MR4 or better) may be eligible to attempt treatment-free remission (TFR).8-11 Clinical trials have demonstrated that patients are more likely to achieve optimal and deeper responses to first-line therapy at key ELN milestones when second-generation (2G) TKIs are used rather than imatinib, but achievement of responses in real-world practice is less well studied, particularly in the second-line setting.12–14 Achievement of ELN-defined responses and how ELN guidelines are implemented in real-world settings are infrequently explored.

An increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) adverse events (AEs) has been described in patients receiving 2G- or third-generation-TKIs compared with imatinib, especially in patients with pre-existing CV risk factors.13-17 Given the excellent long-term outcomes in CML, comorbidities are now a major consideration.18, 19 However, in routine UK clinical practice, it is unclear how physicians assess and manage CV risk factors or how CV risk factors affect TKI management.

UK TARGET CML (CAMN107CGB12) is a retrospective observational study of baseline assessment of patients with CML-CP, TKI treatment pathways, response monitoring patterns and response rates in routine UK National Health Service (NHS) clinical practice; we compared findings with ELN 2013 recommendations.4

Methods

Study design

This retrospective noninterventional study was conducted at 21 UK NHS secondary and tertiary care centres. Data were collected from paper and electronic records. Inclusion criteria included CML-CP diagnosis at the start of first-line TKI, aged ≥18 years and at ≥6 months of follow-up from the date of first TKI (between January 2013 and April 2017). Patients prescribed first TKI in a clinical trial, and patients in accelerated phase (AP) or blast phase (BP) before initiation of first TKI were excluded.

Objectives were to describe TKI treatment pathways in the UK, patient characteristics, practices for assessing and managing CV risk factors before TKI treatment, responses to first- and second-line TKI therapy at ELN time points, recorded reasons for stopping/changing TKIs, adherence to ELN 2013 recommendations and disease progression frequency and management. AE data were not collected.

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, with a cut-off date of 6 June 2018, using Microsoft Excel and STATA (version 13; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). A study size of 200–250 patients in approximately 20 centres (maximum of 40 patients/centre) was expected to give a representative sample of patients in the UK and provide reliable quantitative and qualitative variables.

For comparison with ELN, where data were available, responses were categorised as optimal, warning or failure according to ELN 2013 recommendations.4 If BCR-ABL1 transcript levels were not available on the IS, unconverted BCR-ABL1/ABL1 percentages were used to reflect real-world practices at that centre (all centres used ABL1 as a reference gene). Two of 14 centres (14%) reported on the IS in 2013, increasing to 17/21 (81%) in 2017.

Results

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

Between November 2015 and September 2017, 257 patients (186 from 14 tertiary centres and 71 from seven general hospitals) were enrolled. Median follow-up by the data cut-off was 32·9 months (range, 12·6–58·6). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table I. Clinical characteristics (other than white blood cell counts) and risk scores at diagnosis were not well documented.

The first-line TKI was imatinib in the majority of patients (79%). Reasons for first-line TKI choice were recorded for <50% of patients; the clinician preference of ‘standard first-line choice’ and ‘good results expected’ were the most frequently cited reasons Table SI. First-line imatinib and 2G-TKIs were prescribed to 31/42 (74%) and 11/42 (26%) patients with high Sokal scores, respectively, and 23/34 (68%) and 11/34 (32%) with high European Treatment and Outcomes Study (EUTOS) scores, respectively. Patients receiving a first-line 2G-TKI were younger [median, 46 years (95% CI, 41–53 years)] than those receiving first-line imatinib [median, 55 years (95% CI, 52–59 years); Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0·0128].

CV risk factors and other documented comorbidities at baseline

Among all patients, 149 (58%) had ≥1 recorded comorbidity at baseline (Table I). Seventy-four patients (36%) receiving imatinib had CV comorbidities at baseline vs. seven (13%) receiving a 2G-TKI (Table II). Only 74 patients (29%) had baseline blood pressure documented; 33 (45%) had stage ≥2 hypertension Table SII.20

Exact levels of baseline blood glucose were documented in 58 patients (23%); documentation occurred more often in patients treated with first-line 2G-TKI [20/54 (37%)] vs. imatinib [38/203 (19%)]. Baseline low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol levels were recorded in 23 (9%) and 40 (16%) patients, respectively. CV risk assessment tool use was documented for 10 patients (4%), with the validated QRISK2 tool used in three (1%).

Response monitoring practices

Within 12 months of starting first-line TKI, 250 patients (97%) had ≥1 real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) assessment and 221 patients (86%) had ≥3 RQ-PCR assessments. Two-hundred and four (79%), 177 (69%), and 162 (63%) patients had assessments at the three-, six-, or 12-month ELN milestones (regardless of TKI line), respectively. Cytogenetic testing (chromosome banding analysis or fluorescence in situ hybridisation) was conducted less frequently. Frequency of assessments at ELN milestones on first and second TKI are described in Table III.

First-line TKI therapy

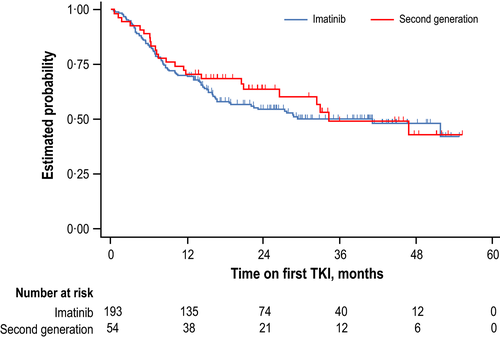

Median follow-up duration on first-line TKI and molecular responses to first-line TKI therapy are shown in Table IV. Time to discontinuation of first TKI for patients on imatinib vs. 2G-TKI is shown in Fig 1. For patients receiving imatinib or nilotinib, respective median starting doses were 400 or 600 mg/day, while 24/203 (12%) and 8/50 (16%) had dose reductions, and 14% and 12% had dose interruptions, respectively.

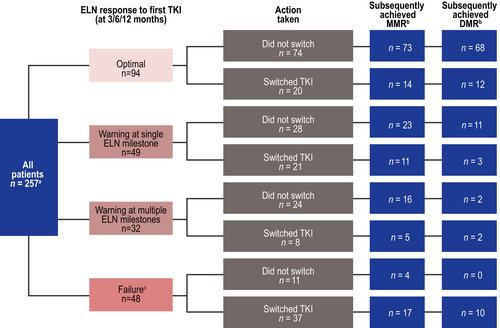

Quantifiable molecular or cytogenetic assessments were performed at ≥1 ELN milestone during first-line TKI in 223 patients (87%) (Fig 2). Forty-eight patients had ≥1 failure, 11 (23%) remained on first-line TKI {median follow-up, 13·8 months [interquartile range (IQR), 12·8–25.9]}, and 37 (77%) switched TKIs [median follow-up, 25·1 months (IQR, 14·3–32.6)].

Second-line TKI therapy

At least one TKI switch occurred in 113 patients (44%); 54 (21%) switched more than once. Reasons for the first switch were resistance in 73 (65%), intolerance in 38 (34%) and other reasons in two (2%) (Table SIII). Thirteen patients (12%) switched to imatinib, 68 (60%) to nilotinib, 20 (18%) to dasatinib, 11 (10%) to bosutinib and one (1%) to ponatinib (Table SIV). For patients receiving second-line imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib and bosutinib, median starting doses (range) were 400 (200–400), 600 (200–800), 100 (50–100) and 300 (100–500) mg/day, respectively.

Median follow-up duration after switching to second TKI was 23·7 months (range, 1·2–54·1) (Table IV). MMR at any time and DMR at any time were observed in 37/51 (73%) and 21/51 (41%) patients, respectively, with ≥13 months' follow-up on second line. Molecular responses to second-line TKI for all patients regardless of follow-up duration are shown in Table V.

Of the 113 patients who switched TKI at least once, 18 (16%) had failure on second-line TKI (Figure S1), seven (39%) remained on that TKI (median follow-up, 24·3 months (IQR, 11·6–31.0)], while 11 (61%) switched again [median follow-up, 27·5 months (IQR, 16·4–33.8)].

Kinase domain mutation analysis

BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutational analysis was performed prior to the first switch in 24 patients (21%), including 20 (27%) who switched due to resistance and four (10%) who switched due to intolerance or other reasons. Clinically actionable mutations were identified in six patients (Table SVI).

Overall TKI pathways

Among all patients, 144 (56%) received only a first-line TKI, and 59 (23%), 35 (14%), 16 (6%) and three (1%) received two, three, four and five TKIs, respectively; sequences of TKI received are described in Table SIV. Eleven patients received the same TKI in multiple lines of therapy.

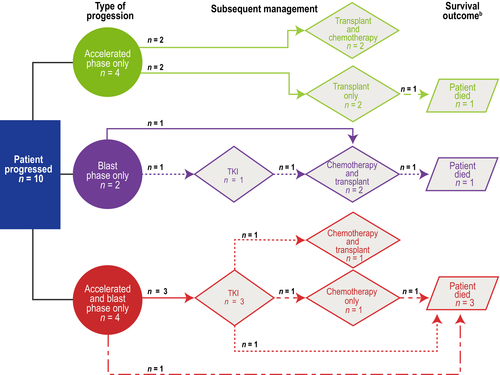

Disease progression

Ten patients progressed to AP and/or BP, and 15 patients died (10 in CP and five after progression). Survival outcomes and treatments to manage progression are summarised in Fig 3.

Discussion

The management of CML has undergone dramatic changes; however, it remains unclear whether real-world practice in the UK has evolved with these developments. We conducted the UK TARGET CML study to assess this question, with a particular focus on (i) TKI treatment pathways, (ii) implementation of ELN recommendations for molecular-based patient management, (iii) attainment of DMR with first- and second-line TKI in real-world practice and (iv) assessment of baseline CV risk factors.

Despite a relatively short median follow-up (<33 months), almost half of the patients switched from first-line TKI, most often due to resistance (65%). In addition, 21% of patients received ≥3 lines of TKIs. This frequency of TKI switching was somewhat higher than that observed in prospective clinical trials, such as the pivotal trial of frontline imatinib [International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS)], which reported that 34% of patients discontinued treatment after six years of follow-up, although no other alternative TKI was available at the time of IRIS recruitment.21 In IRIS long-term follow-up (median, 10·9 years), imatinib discontinuation was most frequently attributed to unsatisfactory therapeutic effect (15·9%), withdrawal of consent (10·3%), or AEs (6·9%).22 Similarly, in the frontline trial of nilotinib [Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Newly Diagnosed Patients (ENESTnd)], treatment discontinuations were most frequently due to suboptimal response/treatment failure or AEs/abnormal laboratory values (12% each by the five-year data cut-off among patients allocated to nilotinib 300 mg twice daily).14 We found that in real-world practice, approximately half of patients required a change of TKI, highlighting the importance of optimal monitoring of molecular responses and treatment-related side effects to ensure proper use of TKIs and timely switching. These data also demonstrated the ongoing challenge of establishing a satisfactory, long-term treatment, with multiple TKI switches being common.

Although 58% of patients had a recorded comorbidity, patients generally had poorly documented baseline clinical characteristics and prognostic scores. Demographic and baseline characteristics were not dissimilar from those of other real-world cohorts,2, 23, 24 although prognostic scores were better documented (98%) in the Swedish CML registry.2 CV events have been reported to be increased with 2G-TKIs,13–15 and CV risk factors should therefore be carefully considered when choosing a TKI. Even with first-line imatinib, it is important to assess CV risk, given that approximately half of patients will require a switch to a 2G-TKI at some point. Although late complications with 2G-TKIs were not fully understood or evaluable at the time of ELN 2013, the guidelines nevertheless recommended continued clinical monitoring of all patients. Several CV risk factors were very poorly documented in our cohort, and any use of validated CV risk tools, such as QRISK2, was rarely documented. Baseline blood pressure was documented in fewer than one-third of patients, and when baseline blood pressure was recorded, it was often elevated, with three patients in hypertensive crisis, illustrating the importance of documenting this parameter so that hypertension can be managed appropriately. However, some evidence was observed that CV comorbidities at baseline played a role in first-line TKI choice, with patients appearing more likely to receive first-line imatinib if a CV comorbidity was documented.

Currently, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends NHS funding in England of imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib in the first line and nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib or ponatinib in later lines.25 In this cohort, first-line treatment was mostly imatinib or nilotinib (<2% received first-line dasatinib), and second-line treatment was mostly nilotinib, reflecting NICE recommendations at the start of treatment for these patients (dasatinib was not routinely available). Patients were more likely to receive first-line 2G-TKIs than imatinib if they were younger and had no documented comorbidities. Overall, prognostic scores were poorly documented despite strong evidence that these risk scores remain highly predictive of disease response in the TKI era.14 We did not find evidence that prognostic scores played a major role in first-line TKI choice, with a majority of patients identified as high risk by Sokal, EUTOS or Hasford criteria being treated with imatinib. Overall, 4% of patients progressed to AP and/or BP, corresponding well with the results of the Swedish CML registry (3% by 12 months).2

One key finding of this study is that ELN 2013 monitoring recommendations were not consistently implemented. Patients frequently did not have assessments at recommended time points. This finding is consistent with those from the SIMPLICITY study, which reported that monitoring was conducted less frequently than recommended, although with higher frequency in Europe than the United States.23 This finding is important because a previous study showed that patients without frequent molecular monitoring were at higher risk of disease progression.26 In addition, frequent molecular monitoring (3–4 times per year) was associated with greater TKI treatment adherence in patients with CML.27

Overall, in our study, 86% of patients had ≥3 molecular response tests during their first year of TKI treatment, while SIMPLICITY reported 46% for Europe,23 a finding which potentially reflects UK-specific practice or changes in practice over time (UK patients who were first treated in 2013–2017 were compared with SIMPLICITY patients first treated in 2010–2015). Furthermore, our UK study observed a relatively high level of testing for early molecular response (EMR) at three months (81%) compared with SIMPLICITY (32%), indicating rapid adoption of molecular monitoring at early milestones in the UK.23

However, despite a generous one-month window applied around ELN milestones, a large proportion of patients (≈20–30%) were still without evaluable molecular or cytogenetic test results at any given time point during their first year of TKI treatment. Moreover, 13% of patients had no evaluable molecular or cytogenetic result at any ELN milestone during the first year of TKI treatment.

ELN recommended that a patient with ELN-defined failure should have their TKI switched to reduce the risk of progression. Nevertheless, a number of patients in TARGET remained on first-line TKI despite ELN-defined treatment failure.

Strikingly, BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutational analyses, recommended by ELN in warning or failure, were infrequently performed, even in patients with documented resistance, despite the known importance of mutation status for subsequent TKI selection. Patients did not always have recommended baseline assessments such as qualitative PCR despite its importance in determining BCR-ABL1 transcript type, which can affect future molecular monitoring, especially at the low levels before consideration for TFR. Furthermore, although bone marrow and cytogenetic analysis still have an essential role in assessment of patients at baseline, many patients were managed without bone marrow or cytogenetic analysis. Bone marrow evaluation before TKI switching was infrequently performed, which may reflect the current use of PCR thresholds for interpretation of resistance.

Clinical trials have shown that 2G-TKIs lead to improved rates of molecular responses compared with imatinib.12-14 In this cohort, observed rates of EMR and MMR at ELN milestones and DMR at any time during first-line TKI were higher with 2G-TKIs than with imatinib, confirming the results in this real-world setting. While EMR and MMR were defined as optimal responses in ELN 2013,4 treatment goals are evolving to include deeper responses and TFR.8, 10, 11 Studies have shown that deeper molecular responses were associated with improved outcomes compared with complete cytogenetic response,6, 7 and a sustained DMR is a prerequisite for attempting TFR in both clinical practice guidelines8, 10, 11 and clinical trials.28, 29 Clinical studies have demonstrated that 2G-TKIs can also lead to improved rates of DMR in the second line.30 Results from our study showed that patients switching from first-line treatment may achieve not only optimal responses but also deeper responses, including patients with prior resistance or ELN-defined failure.

A criticism of observational studies is the increased risk of selection bias and confounding, precluding the robust analysis and conclusions provided by randomised controlled trials. However, real-world evidence plays an important role in allowing physicians to reflect on current practice. Our study demonstrated that almost half of patients required a TKI switch in real-world practice and that optimal and deep responses can be achieved by patients who switch. However, inadequate CV risk assessment, response monitoring, and mutational analysis increased the risk of inappropriate patient management and, as such, the findings of this study highlighted key areas for improvement in care for patients with CML. Further consideration for improving implementation of guidelines in real-world clinical practice, including very recent updates to the ELN recommendations,31 is warranted.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the principal investigators and research teams at each of the 21 UK participating sites who made this study possible. Most importantly, we extend our gratitude to all the patients who consented to be part of this research. We thank OPEN VIE (formerly pH Associates) for their support in the conduct of this research study. We also thank Silvia Sanz, Fiona Read, Michelle Murchie and Rozinder Bains of the Novartis Pharmaceutical UK Ltd haematology medical team for their ongoing input and support in the conduct of this study. We thank Christopher Edwards, PhD, and Karen Kaluza Smith, PhD, of ArticulateScience LLC for their medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. This study was sponsored and funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. The authors had full control of the content and made the final decision for all aspects of this article.

Author contributions

AJM and DM designed the research study, performed the research, analysed the data and wrote the paper. REC and PN designed the research study, performed the research and analysed the data. JR and FG designed the research study, analysed the data and wrote the paper. NCPC, LF and SJC designed the research and analysed the data. FWa, JB, FLD, SA, MD, JT, MFM, GC, BH, FWi, MS, MR and SM performed the research and analysed the data.

Conflict of interests

AJM participated in advisory boards for Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and Pfizer, and received honoraria, research funding, travel, accommodations and expenses from Novartis. REC participated in advisory boards for Novartis, BMS and Pfizer and received honoraria, research funding, travel, accommodations and expenses from Novartis, BMS and Pfizer. NCPC participated in advisory boards for Novartis, BMS and Pfizer; received honoraria from Novartis, BMS, Pfizer and Ariad/Incyte; and received research funding from Novartis, BMS and Pfizer. FLD received honoraria, travel, accommodations and expenses from Novartis and Pfizer. MFM participated in advisory boards for Novartis and received honoraria from Novartis, Pfizer and BMS. SM participated in advisory boards for Novartis, BMS and Pfizer and received honoraria, research funding, travel, accommodations and expenses from Novartis. FWa received educational grants from Pfizer and Novartis. MR participated in advisory boards and received honoraria from Novartis. JB participated in advisory boards and received honoraria from Novartis, Pfizer and Incyte. SA participated in advisory boards and received honorarium, travel and accommodations from Novartis. MD received honoraria from Novartis and Pfizer and research funding from Novartis. JT received support for conference attendance from Novartis. BH participated in advisory boards for Novartis, Pfizer and BMS. FWi received honoraria, travel, accommodation and expenses from Novartis. DM received honoraria from Incyte, Novartis, Pfizer and BMS. JR and SJC are employees and shareholders of Novartis. LF is a former employee and shareholder of Novartis. FG is an employee of OPEN VIE contracted by Novartis. PN, MS and GC declared no conflict of interest.

|

All patients (n = 257) |

First-line imatinib (n = 203) |

First-line 2G-TKI (n = 54) |

First-line nilotinib (n = 50) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 144 (56) | 119 (59) | 25 (46) | 24 (48) |

| Female | 113 (44) | 84 (41) | 29 (54) | 26 (52) |

| Age at initiation of first-line TKI, median [range (IQR)], years | 53·5 [18·4–92·4 (38·8–65.8)] | 55·4 [18·4–92·4 (39·9–67.4)] | 45·8 [20·3–79·5 (36·4–59.6)] | 45·1 [20·3–79·5 (36·1–59.6)] |

| Time from CML diagnosis to start of first TKI, median (IQR), days | 7·0 (1·0–20·0) | 8·0 (2·0–20·3) | 6·0 (1·0–11·0) | 6·0 (1·0–11·0) |

| Assessments prior to first-line TKI, n (%) | ||||

| RQ-PCR | 169 (66) | 140 (69) | 29 (54) | 26 (52) |

| Qualitative PCR (b2a2, b3a2, other) | 140 (54) | 107 (53) | 33 (61) | 30 (60) |

| CBA | 180 (70) | 146 (72) | 34 (63) | 31 (62) |

| FISH | 155 (60) | 117 (58) | 38 (70) | 34 (68) |

| CBA or FISH (bone marrow) | 154 (60) | 119 (59) | 35 (65) | 32 (64) |

| CBA or FISH (peripheral blood) | 54 (21) | 45 (22) | 9 (17) | 9 (18) |

| Both CBA/FISH and RQ-PCR | 139 (54) | 117 (58) | 22 (41) | 20 (40) |

| Treatment for CML prior to first-line TKI, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 126 (49) | 97 (48) | 29 (54) | 26 (52) |

| Prior treatment*, † | ||||

| Hydroxycarbamide | 116 (92) | 89 (92) | 27 (93) | 24 (92) |

| Leukapheresis | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Anagrelide | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Interferon | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Aspirin | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (4) |

| No | 128 (50) | 104 (51) | 24 (44) | 23 (46) |

| Unknown | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Ph chromosome at baseline | ||||

| Yes | 212 (82) | 175 (86) | 37 (69) | 35 (70) |

| No | 3 (1) | 1 (<1) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Unknown | 42 (16) | 27 (13) | 15 (28) | 13 (26) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| WBC count, median (IQR), 109/l | 82·4 (31·2–177·3) | 77·0 (31·2–158·0) | 92·9 (32·3–201·4) | 92·1 (32·5–198·9) |

| Unknown, n (%)‡ | 4 (2) | 1 (<1) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Platelet count, median (IQR), 109/l | 404·0 (252·5–603·0) | 393·5 (244·8–603·0) | 439·0 (339·0–578·0) | 441·0 (342·8–589·3) |

| Unknown, n (%)‡ | 14 (5) | 11 (5) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Basophils, median (IQR), % | 3·9 (2·0–7·0) | 3·3 (2·0–6·0) | 5·0 (2·3–8·0) | 4·0 (2·3–8·3) |

| Unknown, n (%)‡ | 59 (23) | 46 (23) | 13 (24) | 13 (26) |

| Eosinophils, median (IQR), % | 2·0 (1·1–3·7) | 2·0 (1·1–3·5) | 2·0 (1·3–3·7) | 2·0 (1·3–3·0) |

| Unknown, n (%)‡ | 58 (23) | 45 (22) | 13 (24) | 13 (26) |

| Blasts, median (IQR) (%) | 2·0 (1·0–4·8) | 2·0 (1·0–3·4) | 3·0 (1·6–8·4) | 3·0 (1·5–6·0) |

| Unknown, n (%)‡ | 101 (39) | 77 (38) | 24 (44) | 23 (46) |

| Spleen size below costal margin, median (IQR), cm§ | 1·3 (0·0–10·1) | 1·0 (0·0–10·1) | 4·0 (0·0–10·3) | 2·0 (0·0–10·0) |

| Unknown, n (%)‡ | 85 (33) | 67 (33) | 18 (33) | 17 (34) |

| Sokal risk score, n (%)¶ | ||||

| Low risk | 52 (20) | 43 (21) | 9 (17) | 8 (16) |

| Intermediate risk | 54 (21) | 41 (20) | 13 (24) | 13 (26) |

| High risk | 42 (16) | 31 (15) | 11 (20) | 9 (18) |

| No score recorded and required components not all recorded | 109 (42) | 88 (43) | 21 (39) | 20 (40) |

| EUTOS score, n (%)** | ||||

| Low risk | 110 (43) | 90 (44) | 20 (37) | 19 (38) |

| High risk | 34 (13) | 23 (11) | 11 (20) | 9 (18) |

| No score recorded and required components not all recorded†† | 113 (44) | 90 (44) | 23 (43) | 22 (44) |

| Hasford score, n (%)‡‡ | ||||

| Low risk | 25 (10) | 19 (9) | 6 (11) | 5 (10) |

| Intermediate risk | 35 (14) | 32 (16) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) |

| High risk | 19 (7) | 13 (6) | 6 (11) | 4 (8) |

| No score recorded and required components not all recorded | 178 (69) | 139 (68) | 39 (72) | 38 (76) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| None recorded | 108 (42) | 80 (39) | 28 (52) | 26 (52) |

| ≥1 recorded§§, ¶¶ | 149 (58) | 123 (61) | 26 (48) | 24 (48) |

| CV comorbidities | 81 (32) | 74 (36) | 7 (13) | 6 (12) |

| Diabetes | 25 (10) | 21 (10) | 4 (7) | 4 (8) |

| Respiratory disease | 20 (8) | 17 (8) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) |

| Renal disease | 16 (6) | 14 (7) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Non-haematological cancer | 9 (4) | 8 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Hepatic disease | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 86 (33) | 70 (34) | 16 (30) | 15 (30) |

- 2G-TKI, second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CBA, chromosome banding analysis; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; CV, cardiovascular; EUTOS, European Treatment and Outcomes Study; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation; IQR, interquartile range; Ph, Philadelphia chromosome; RQ-PCR, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction; WBC, white blood cell.

- * Patients may have received multiple prior treatments.

- † Proportion of patients with each prior treatment was calculated out of the total number of patients who received prior treatment.

- ‡ Proportion of patients with unknown clinical characteristics was calculated out of the total number of patients in each column.

- § Spleens reported to be ‘normal’ or ‘nonpalpable’ were considered to be 0 cm below the costal margin.

- ¶ Among 148 patients who received any first-line TKI and had an available Sokal risk score at diagnosis, the score was documented for 96 (65%), and not documented and instead calculated during this analysis for 52 (35%).

- ** Among 144 patients who received any first-line TKI and had an available EUTOS risk score at diagnosis, the score was documented for 36 (25%), and not documented and instead calculated during this analysis for 108 (75%).

- †† Includes patients who had a risk category recorded but no score recorded.

- ‡‡ Hasford scores were not collected in case report forms and were calculated if required data were available.

- §§ Patients may have had multiple comorbidities.

- ¶¶ Proportion of patients with each comorbidity was calculated out of the total number of patients in each column.

| n (%) |

All patients (n = 257) |

First-line imatinib (n = 203) |

First-line 2G-TKI (n = 54) |

First-line nilotinib (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 25 (10) | 21 (10) | 4 (7) | 4 (8) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Documented* | 174 (68) | 140 (69) | 34 (63) | 32 (64) |

| Current smoker | 38 (22) | 35 (25) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) |

| Ex-smoker | 46 (26) | 39 (28) | 7 (21) | 6 (19) |

| Never smoked | 88 (51) | 65 (46) | 23 (68) | 22 (69) |

| Unclear | 2 (1)† | 1 (1)† | 1 (3)† | 1 (3)† |

| BMI > 30 documented | 16 (6) | 14 (7) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| CV comorbidities | ||||

| None recorded | 176 (68) | 129 (64) | 47 (87) | 44 (88) |

| ≥1 recorded‡, § | 81 (32) | 74 (36) | 7 (13) | 6 (12) |

| Hypertension | 58 (23) | 52 (26) | 6 (11) | 5 (10) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 28 (11) | 26 (13) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 14 (5) | 12 (6) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 (4) | 10 (5) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 9 (4) | 8 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Arrhythmias | 8 (3) | 7 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Unstable angina | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| History of CV disease | ||||

| Not documented | 101 (39) | 80 (39) | 21 (39) | 20 (40) |

| Documentation unknown¶ | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Documented** | 155 (60) | 122 (60) | 33 (61) | 30 (60) |

| No history | 26 (17) | 23 (19) | 3 (9) | 3 (10) |

| Details of history not provided | 104 (67) | 76 (62) | 28 (85) | 25 (83) |

| Details of history provided | 25 (16) | 23 (19) | 2 (6) | 2 (7) |

| Family history of CV disease | ||||

| Not documented | 159 (62) | 128 (63) | 31 (57) | 29 (58) |

| Documentation unknown¶ | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

| Documented | 97 (38) | 74 (36) | 23 (43) | 21 (42) |

- 2G-TKI, second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular.

- * Proportion of patients in each smoking category was calculated based on the number of patients with documented smoking status.

- † Two patients were recorded as ‘does not smoke’; it was unclear whether they were ex-smokers or never smoked.

- ‡ Patients could be listed as having >1 CV comorbidity.

- § Proportion of patients with CV comorbidities was calculated based on total number of patients in each column.

- ¶ One patient was transferred from another hospital prior to TKI treatment; it was unclear if this patient's personal or family history of vascular disease had been documented prior to TKI treatment.

- ** Proportion of patients within each category was calculated based on the number of patients who had documented CV disease history.

|

All patients n (%) |

Imatinib first line n (%) |

Second-generation first line n (%) |

Nilotinib first line n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First TKI | ||||

| RQ-PCR | ||||

| 3 months* | 180/223 (81) | 143/173 (83) | 37/50 (74) | 35/47 (74) |

| 6 months† | 141/199 (71) | 105/154 (68) | 36/45 (80) | 34/42 (81) |

| 12 months‡ | 117/170 (69) | 95/132 (72) | 22/38 (58) | 21/35 (60) |

| CBA/FISH | ||||

| 3 months* | 15/223 (7) | 15/173 (9) | 0/50 (0) | 0/47 (0) |

| 6 months† | 9/199 (5) | 8/154 (5) | 1/45 (2) | 1/42 (2) |

| 12 months‡ | 2/170 (1) | 2/132 (2) | 0/38 (0) | 0/35 (0) |

| CBA/FISH and/or RQ-PCR | ||||

| 3 months* | 186/223 (83) | 148/173 (86) | 38/50 (76) | 36/47 (77) |

| 6 months† | 151/199 (76) | 114/154 (74) | 37/45 (82) | 35/42 (83) |

| 12 months‡ | 117/170 (69) | 95/132 (72) | 22/38 (58) | 21/35 (60) |

| Second TKI | ||||

| RQ-PCR | ||||

| 3 months* | 63/82 (77) | 8/10 (80) | 55/72 (76) | 43/54 (80) |

| 6 months† | 44/66 (67) | 4/8 (50) | 40/58 (69) | 31/46 (67) |

| 12 months‡ | 27/52 (52) | 4/8 (50) | 23/44 (52) | 19/39 (49) |

| CBA or FISH | ||||

| 3 months* | 12/82 (15) | 2/10 (20) | 10/72 (14) | 9/54 (17) |

| 6 months† | 4/66 (6) | 0/8 (0) | 4/58 (7) | 4/46 (9) |

| 12 months‡ | 1/52 (2) | 0/8 (0) | 1/44 (2) | 1/39 (3) |

| CBA/FISH and/or RQ-PCR | ||||

| 3 months* | 65/82 (79) | 8/10 (80) | 57/72 (79) | 45/54 (83) |

| 6 months† | 45/66 (68) | 4/8 (50) | 41/58 (71) | 32/46 (70) |

| 12 months‡ | 27/52 (52) | 4/8 (50) | 23/44 (52) | 19/39 (49) |

| ≥1 assessment at an ELN milestone (first- or second-line TKI)* | 239/257 (93) | 189/203 (93) | 50/54 (93) | 48/50 (96) |

- CBA, chromosome banding analysis; ELN, European LeukemiaNet; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation; RQ-PCR, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

- * Denominator included patients with ≥4 months' follow-up on that TKI.

- † Denominator included patients with ≥7 months' follow-up on that TKI.

- ‡ Denominator included patients with ≥13 months' follow-up on that TKI.

| Overall responses | First-line TKI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

First-line imatinib (n = 203) |

First-line 2G-TKI (n = 54)† |

All patients (n = 257) |

First-line imatinib (n = 203) |

First-line 2G-TKI (n = 54)† |

First-line nilotinib (n = 50) |

All patients (n = 257) | |

| Median follow-up duration‡ on each TKI (range), months | 33·3 (12·6–58·6) | 30·0 (13·2–56·8) | 32·9 (12·6–58·6) | 16·7 (0·5–54·8) | 20·8 (0·5–55·3) | 21·3 (0·5–55·3) | 17·5 (0·5–55·3) |

| EMR at 3 months (±1 month), in patients with 3-month molecular response assessments, n (%) | 88/163 (54) | 29/41 (71) | 117/204 (57) | 88/156 (56) | 28/38 (74) | 26/36 (72) | 116/194 (60) |

| MMR by 12 months (±1 month), n (%) | 84 (41) | 28 (52) | 112 (44) | 71 (35) | 26 (48) | 25 (50) | 97 (38) |

| MMR at any time, n (%) | 156 (77) | 42 (78) | 198 (77) | 102 (50) | 34 (63) | 32 (64) | 136 (53) |

| DMR at any time, n (%) | 95 (47) | 35 (65) | 130 (51) | 58 (29) | 29 (54) | 27 (54) | 87 (34) |

- 2G-TKI, second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor; DMR, deep molecular response; EMR, early molecular response; IS, International Scale; MMR, major molecular response.

- * Patients could appear in multiple molecular response categories. Molecular responses were assessed as EMR (BCR-ABL1IS ≤10% at three months), MMR (BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·1%) by 12 months, MMR at any time and DMR (BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·01%) at any time. To account for variations in real-world appointment scheduling, a window of ± one month was applied to ELN-defined time points; if multiple assessments were available within the window, the one closest to the time point was used.

- † Fifty patients received first-line nilotinib, and four received first-line dasatinib.

- ‡ The columns for overall response reported the duration of follow-up for all TKI therapies, including later-line TKIs in patients who switched from their first-line TKI (from start of first-line TKI to most recent data collection, akin to an intention-to-treat analysis). The columns for first-line TKI therapy reported the duration of follow-up for only first-line TKI therapy (from start of first-line TKI to most recent data collection or death in patients who continued receiving first-line TKI or to end of first-line TKI for patients who switched to a second-line TKI).

|

All switched patients (n = 113) |

Second-line imatinib (n = 13) |

Second-line 2G-TKI (n = 100)† |

Second-line nilotinib (n = 68) |

Switched to second line for resistance (n = 73) |

Switched to second line for intolerance or other reason (n = 40)‡ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up post first switch (range), months§ | 23·7 (1·2–54·1) | 22·5 (4·9–43·0) | 23·9 (1·2–54·1) | 29·7 (1·2–52·4) | 27·4 (1·2–51·4) | 20·1 (2·8–54·1) |

| Median follow-up on second-line TKI (range), months¶ | 23·9 (13·6–50·2) | 19·2 (13·6–43·0) | 28·6 (13·9–50·2) | 27·3 (13·9–50·2) | 25·6 (13·9–46·5) | 20·3 (13·6–50·2) |

| EMR at 3 months (±1 month) on second TKI in patients with 3-month molecular response assessments, n (%)** | 59/70 (84) | 10/10 (100) | 49/60 (82) | 38/45 (84) | 39/47 (83) | 20/23 (87) |

| MMR by 12 months (±1 month) on second TKI, n (%)†† | 30/50 (60) | 4/7 (57) | 26/43 (60) | 24/38 (63) | 21/35 (60) | 9/15 (60) |

| MMR at any time on second TKI, n (%)†† | 37/51 (73) | 4/8 (50) | 33/43 (77) | 29/38 (76) | 27/36 (75) | 10/15 (67) |

| DMR at any time on second TKI, n (%)†† | 21/51 (41) | 2/8 (25) | 19/43 (44) | 17/38 (45) | 15/36 (42) | 6/15 (40) |

- 2G-TKI, second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor; DMR, deep molecular response; EMR, early molecular response; IS, International Scale; MMR, major molecular response.

- * Patients could appear in multiple molecular response categories. Molecular responses after switch to second TKI were assessed as EMR (BCR-ABL1IS ≤10% at three months), MMR (BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·1%) by 12 months, MMR at any time and DMR (BCR-ABL1IS ≤0·01%) at any time. To account for variations in real-world appointment scheduling, a window of ± one month was applied to ELN-defined time points; if multiple assessments were available within the window, the one closest to the time point was used.

- † Switched to 2G-TKI (n = 68 nilotinib, n = 20 dasatinib, n = 11 bosutinib, n = 1 ponatinib).

- ‡ Switched for intolerance (n = 38) or switched for another reason (n = 2).

- § Duration from start of second-line TKI to last data collection or death (included patients with ≥1 switch).

- ¶ Duration from start of second-line TKI to last data collection, date of switch to a third-line TKI, or death.

- ** EMR defined as BCR-ABL1IS ≤10% at three months (±1 month); only those patients with BCR-ABL1 available at three months were included.

- †† MMR (≤0·1% BCR-ABL1); DMR (≤0·01% BCR-ABL1); only those patients with ≥13 months' follow-up were included.