Pain and opioid use after reversal of sickle cell disease following HLA-matched sibling haematopoietic stem cell transplant

The burden of pain varies among patients with sickle cell disease (SCD). Chronic pain, resulting from multiple aetiologies, is common in SCD. The Analgesic, Anaesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations Innovations Opportunities and Networks-American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy (ACTTION- AAPT) criteria have recently described subcategories of chronic SCD pain (Dampier et al, 2017). Haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is the most accessible curative therapy for SCD resulting in disease-free survival in over 85% (Hsieh et al, 2014; Gluckman et al, 2017). After successful HSCT (as defined by haematological parameters), most patients are weaned off opioids; however, a subgroup of patients continues to experience pain that requires opioid treatment.

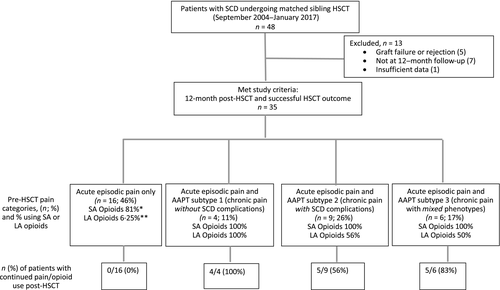

We determined the prevalence and correlates of pain requiring continued opioid treatment at 12 months after successful non-myeloablative human leucocyte antigen-matched sibling allogeneic HSCT in a cohort of SCD patients (Fig 1)(Hsieh et al, 2014). The Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health approved the protocol. All participants provided informed consent. Detailed data on the clinical course, pain, opioid use and laboratory values were prospectively collected within 3 months prior to HSCT and at 12 months post-HSCT (n = 35). Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures were also prospectively collected at the same time points in a subgroup of these patients (n = 20). The PROMIS domains assessed included pain intensity, pain impact, anxiety, depression, satisfaction with social role, physical function, fatigue and sleep disturbance (Cella et al, 2007; Keller et al, 2017). All PROMIS raw data were converted to T-scores.

Based on pain history pre-HSCT, patients reporting chronic pain were classified using AAPT guidelines (Dampier et al, 2017) into one of following three chronic pain subtypes: (i) AAPT subtype 1 - chronic pain without contributory SCD complications (e.g. avascular necrosis or leg ulcers), (ii) AAPT subtype 2 - chronic pain with evidence of contributory SCD complications based on clinical signs or test results (iii) AAPT subtype 3 - chronic pain with mixed pain types if there was evidence of contributory SCD complications and also pain in unrelated sites (e.g. arms, back, chest or abdominal pain). Patients who only experienced acute episodic pain were grouped separately (Episodic pain only) (Fig 1). Non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, version 24·0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Given the limited sample size, descriptive statistics were reported primarily. When direct statistical comparisons were required, Independent samples Mann-Whitney U or Chi-squared Tests were used.

The median age of the cohort was 32 years (range: 16–65 years) and 21 (60%) patients were male. Pre-HSCT (Fig 1), all patients had experienced intermittent episodes of acute pain; 16 (46%) had acute episodic pain only, 4(11%) also had chronic pain without SCD complications (AAPT-1), 9 (26%) also had chronic pain with contributory SCD complications (AAPT-2) and 6 (17%) also had mixed pain phenotype (AAPT-3). Post-HSCT, haematological parameters improved in all patients (Table 1) (Hsieh et al, 2014). Median pain-related admissions decreased significantly [from 3 admissions/year (range 0–24) pre-HSCT to 0 (range 0–3) post-HSCT; (P < 0·001)]. Overall, there was significant reduction in the prescription of both short- and long-acting opioids pre- vs. post-HSCT (91% to 40% for short-acting and 40% to 14% for long-acting opioids; P < 0·001). At 12 months post-HSCT, 14 of 35 (40%) patients reported persistent pain requiring opioids. Examination of continued opioid use patterns, showed that all four patients (100%) in AAPT-1 and five of six (83%) in AAPT-3, continued to use opioids to manage their pain while 4 of 9 patients (44%) in AAPT-2 and all patients in the Episodic pain only group stopped using opioids post-HSCT (Table 1).

| Acute episodic pain only (n = 16) | Chronic pain without SCD complications (AAPT subtype 1) (n = 4) | Chronic pain with SCD complications (AAPT subtype 2) (n = 9) | Chronic pain with mixed pain phenotype (AAPT subtype 3) (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at HSCT (years) | 25 (16–41) | 34·5 (23–65) | 36 (22–53) | 34 (19–47) |

| Gender | 6 F + 10 M | 3 F + 1 M | 2 F + 7 M | 3 F + 3 M |

| Hydroxycarbamide pre-HSCT (mg) | 1250 (500–2500) | 2000 (1500–2500) | 1500 (1000–2000) | 1750 (500–2000) |

| Pre-HSCT | Post-HSCT | Pre-HSCT | Post-HSCT | Pre-HSCT | Post-HSCT | Pre-HSCT | Post-HSCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions for pain/year n (range) | 2 (0–24) | 0 (0) | 6 (3–9) | 0·5 (0–2) | 2 (0–10) | 0 (0) | 4·5 (3–15) | 0 (0–3) |

| Short-acting opioids use n (%) | 13/16 (81%) | 0 (0) | 4/4 (100%) | 4/4 (100%) | 9/9 (100%) | 5/9 (56%) | 6/6 (100%) | 5/6 (83%) |

| Long-acting opioids use n (%) | 1/16 (6·25%) | 0 (0) | 4/4 (100%) | 1/4 (25%) | 5/9 (56%) | 1/9 (11%) | 3/6 (50%) | 3/6 (50%) |

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 92 (72–105) | 135 (102–168) | 90 (74–92) | 106 (72–126) | 83 (67–105) | 142 (99–195) | 88 (77–98) | 119 (105–135) |

| Donor red cell phenotype achieved | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes |

- AAPT, ACTTION- American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy; HSCT, haematopoietic stem cell transplant; N/A, not applicable; SCD, sickle cell disease. Data displayed as median and range.

Analysis of pre- and post-HSCT PROMIS data in a subgroup of patients (n = 20) showed significant improvement in the subscales of pain intensity (P = 0·03), pain impact (P = 0·007), satisfaction with social role (P = 0·03) and physical function (P = 0·004) following HSCT. No significant changes were seen for fatigue (P = 0·09), anxiety, depression or sleep disturbance, which could be related to small sample size (Table 2). However, when comparing patients with persistent pain post-HSCT (AAPT-1 and AAPT-3) (n = 6) versus those with resolved pain post-HSCT (n = 8), pre-HSCT anxiety ratings were significantly higher in the group with unexplained, persistent pain (P = 0·05). Additional pre-HSCT factors that were associated with unexplained, persistent pain post-HSCT included higher burden of pain as defined by higher median pain admissions/year (2 (0–10) vs. 5·5 (3–9); P = 0·04); higher overall numerical pain rating on a 0-10 scale [2 (0–5) vs. 6 (5–7); P = 0·02] and treatment with long acting opioids (0% vs. 83%; P < 0·001) (Table S1).

| PROMIS Measures (n = 20) | Pre-HSCT | Post-HSCT | Post-HSCT outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity (NRS 0–10)a | 4·5 (0–8) | 0·5 (0–7) | Improved (P < 0·05) |

| Pain impacta | 59·9 (40·7–77) | 40·7 (34·9–77) | Improved (P < 0·05) |

| Physical functionb | 43·5 (32–59·2) | 59·2 (32–59·2) | Improved (P < 0·05) |

| Satisfaction with social roleb | 50 (26·9–66·1) | 55·7 (30·8–66·1) | Improved (P < 0·05) |

| Fatiguea | 53 (33·1–65·3) | 42·7 (33·1–72·4) | Unchanged (trend towards improvement, P = 0·09) |

| Anxietya | 49·4 (37·1–66·6) | 44·6 (37·1–74·1) | Unchanged (n/s) |

| Depressiona | 46·1 (38·2–64·9) | 46·1 (30·5–81·3) | Unchanged (n/s) |

| Sleep disturbancea | 53·4 (30·5–77·6) | 47·9 (30·5–74·1) | Unchanged (n/s) |

- HSCT, haematopoietic stem cell transplant; NRS, numeric rating scale; PROMIS, patient reported outcome measures information system.

- a Higher scores in these measures indicate more suffering.

- b Higher scores in these measures indicate better health.

Successful HSCT leads to resolution of pain in the large majority of SCD patients. Pre-HSCT characteristics of the subgroup of patients reporting persistent pain/opioid use post-HSCT included older age (33·5 vs. 22·5 years; P = not significant), significantly higher pain burden (more pain admissions and higher pain intensity ratings), more symptoms of anxiety and more probable use of long-acting opioids pre-HSCT. Utilizing AAPT chronic pain subtypes in SCD, our analysis also shows that pain outcomes post-HSCT may be influenced by pre-HSCT pain characteristics. In our cohort, patients with persistent pain were more likely to have chronic pain without contributory SCD complications or the mixed pain phenotype pre-HSCT. These findings confirm the complex neurobiology of pain in SCD, where different mechanisms may contribute to pain (Darbari et al, 2014). Interestingly, while none of our patients on short-acting opioids experienced continued pain, use of long-acting opioids was associated with continued pain. This may be a reflection of more severe disease in this group; however, contributions from other factors, such as opioid-induced hyperalgesia, central sensitization or genetic predisposition cannot be ruled out (Campbell et al, 2016; Carroll et al, 2016).

The strengths of this transplant cohort include prospective longitudinal surveys of pain and quality of life analyses pre- and post-HSCT compared to previous studies (Beverung et al, 2015; Walters et al, 2016). Additionally, our cohort suffered no acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), thus the burden of pain was not confounded by GvHD. Limitations of the study include lack of mechanistic studies and a follow-up period limited to 12 months post-HSCT. Nonetheless, our study provides the rationale for addressing clinical and psychological comorbidities pre-HSCT, and even considering HSCT at a younger age before development of these complications, to improve outcomes post-HSCT.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the intramural research programs of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States.

Author contributions

Performed the research: DSD, JL, AI, SM, MR, CDF, JFT, SLT, MH. Designed the research study: DSD, JL, SLT, JFT, MH. Analysed the data: DSD, JL, MH. Wrote the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript: DSD, JL, AI, SM, MR, CDF, JFT, SLT, MH.

Competing interests

None.