High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation may only be applicable to selected patients with secondary CNS diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) remains challenging, with median overall survival (OS) <6 months.(Hollender et al, 2000) Induction therapy containing high-dose antimetabolites followed by CNS-penetrating conditioning regimens as part of autologous stem cell rescue (ASCT) may improve outcomes, with 2-year OS rates of 51–68%. (Korfel et al, 2013; Chen et al, 2015; Ferreri et al, 2015a) To evaluate the efficacy of a similar approach, we reviewed our databases to identify patients with DLBCL and CNS involvement incident between 1997 and 2015, excluding patients managed without specifically documented intent to perform high-dose therapy and ASCT. We retrieved clinical characteristics, treatment patterns and outcomes. Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were calculated from date of CNS involvement to date of disease progression or death from any cause and to death from any cause or last follow-up, respectively, with patients who were alive and free from disease progression censored at the date of last follow-up. Survival times were estimated using the product-limit method (Kaplan & Meier, 1958). Median follow-up was calculated from the observation time of patients alive at last follow-up. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics and categorical variables with frequency tables. STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses. P-values were two-sided and values <0.05 were considered significant.

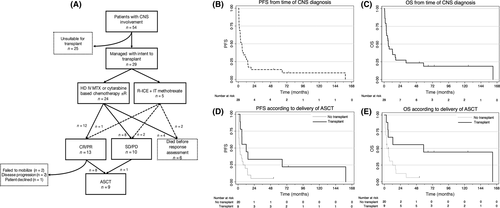

We identified 54 consecutive patients, of whom 25 were considered unsuitable for ASCT due to age (n = 13), co-morbidities (n = 11) or previous transplant (n = 2), leaving 29 managed with specifically documented intention to perform ASCT (Table 1). Twenty-four patients received high-dose anti-metabolite containing regimens, while five (with concurrent leptomeningeal and systemic lymphoma) received rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide with intrathecal methotrexate. Peri-transplant radiation was incorporated in 7 (23%) patients (whole brain in five, brainstem and full cranio-spinal in one patient each). Complete and partial responses to induction were observed in 9 (31%) and 4 (14%) patients respectively, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 44%. Two patients (7%) died from refractory lymphoma and 4 (14%) from treatment-related toxicity in the setting of refractory lymphoma. Of the 13 patients who achieved a response, 8 proceeded to transplant while 5 patients did not, because of failure to collect sufficient autologous stem cells (n = 2), disease progression prior to transplant (n = 2) or patient preference (n = 1). Additionally, one with stable disease also proceeded to ASCT. A flowchart summarizing treatment disposition is provided in Fig 1A. The conditioning regimens used were carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan (n = 7, 78%), carmustine, cyclophosphamide and etoposide (n = 1, 11%) and thiotepa/carmustine (n = 1, 11%). After a median observation period of 58 months (range 1–125), 23 (79%) patients have died. The causes of death were progressive lymphoma (n = 15, 65%), treatment-related toxicity with lymphoma in remission (n = 2, 9%) or with progressive lymphoma (n = 5, 22%) and unrelated (n = 1, 5%). Among these 29 patients, the median PFS and OS were 5.2 and 6 months; the actuarial 5-year PFS and OS rates were 12% (95%CI 3–29) and 18% (95%CI 6–36) respectively (Fig 1B,C). Those patients who received ASCT had longer median PFS (12 vs. 3 months, P = 0.03) and OS (59 vs. 4 months, P = 0.02) (Fig 1D,E). Among the five patients who achieved a response but did not undergo ASCT, 4 patients died at 2 months (ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm), 16, 17 and 32 months (from progressive lymphoma). One patient (who declined ASCT) remains alive and free from disease recurrence at 52 months. Of the original 54 patients, 24 received no CNS prophylaxis, 9 received systemic therapy alone (high-dose methotrexate ± cytarabine), 11 received intrathecal therapy alone and 8 received both systemic and intrathecal. Data were unavailable in one patient. Receipt of CNS prophylaxis (in any form) during first-line therapy was associated with neither PFS nor OS following the subsequent development of CNS involvement (data not shown).

| Patient characteristics | Number with evaluable data | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, (range) years | 29 | 57 (23–76) |

| Female | 29 | 11 (38%) |

| HIV sero-positive | 29 | 0 (0%) |

| Disease setting at time of secondary CNS involvement | ||

| Initial diagnosis | 29 | 3 (10%) |

| First relapse | 22 (73%) | |

| Second or subsequent relapse | 5 (17%) | |

| Median interval from initial diagnosis to development of CNS involvement (range) months | 29 | 7.8 (0–108) |

| First line chemotherapy | ||

| CHOP | 29 | 25 (86%) |

| MACOPB | 2 (7%) | |

| Hyper-CVAD | 2 (7%) | |

| Rituximab as part of primary therapy | 29 | 25 (86%) |

| Evidence of systemic lymphoma at time of secondary CNS involvement | 29 | 21 (72%) |

| Location of CNS involvement | ||

| Parenchymal | 29 | 15 (52%) |

| Leptomeningeal | 8 (28%) | |

| Both | 6 (20%) | |

| Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase | 23 | 18 (79%) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score >1 | 29 | 18 (62%) |

| Treatment after documented CNS involvement | ||

| CNS directed chemotherapy | ||

| High-dose IV methotrexate and cytarabine ± R | 29 | 11 (38%) |

| High-dose IV methotrexate alone ± R | 1 (3%) | |

| R-DHAP | 5 (17%) | |

| R-MPV | 7 (23%) | |

| R-ICE + intrathecal methotrexate | 5 (17%) | |

| Median intravenous methotrexate dose g/m2 (range) | 12 | 3 (1–3.5) |

| Median number of cycles of high-dose antimetabolite therapy delivered (range) | 24 | 2 (1–9) |

| Rituximab as part of therapy | 29 | 20 (79%) |

- CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; R, rituximab; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone; MACOPB, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, bleomycin, Hyper-CVAD, hyper-fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin dexamethasone; IV, intravenous; R, rituximab; R-DHAP, rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine; cisplatin; R-MPV, rituximab, mitomycin; vinblastine, cisplatin; R-ICE, rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide.

In this series of 54 consecutive patients with DLBCL and CNS involvement, due to age or comorbidities, only 29 (54%) were considered candidates for high-dose therapy and ASCT. However, only 9 (17%) were eventual recipients of the procedure, due largely to the modest ORR following anti-metabolite containing regimens. Our findings were consistent with other investigators who have reported markedly improved OS among those with responsive disease who ultimately proceeded to ASCT in retrospective series.(Maziarz et al, 2013; Damaj et al, 2015) Three prospective studies have evaluated ASCT in SCNSL. Ferreri et al (2015a) treated 38 patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma and CNS involvement (16 at initial lymphoma presentation). Following two cycles of high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine-based induction, the ORR was 26%; after ‘intensification’ using high-dose cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, rituximab and etoposide it increased to 82%, and 20 (53%) of patients underwent ASCT. (Ferreri et al, 2015a) The 5-year OS among all patients was 41%; but among those who received ASCT it was 68%. Korfel et al (2013) treated 30 patients with SCNSL in a phase II multicentre study using a high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine-based induction, with an ORR of 74% prior to ASCT; 24 patients (80%) received ASCT and their 2-year OS was 68%. Investigators from Boston explored a high-dose cytarabine (3 g/m2 × 4) and rituximab (1000 mg/m2 IV × 2) based mobilization followed by thiotepa, busulfan and cyclophosphamide based ASCT – the 2-year OS among the 12 patients with SCNSL was 51%.(Chen et al, 2015) Although intensified therapy may be beneficial in appropriately selected patients our data illustrates that in our experience, relatively few patients are able to receive high-dose therapy. However, the minority who do have reasonable outcomes. Our data are limited by the retrospective study design, relatively small sample size, and the effects of both selection and guarantee-time bias in favour of patients who achieved a response to therapy and survived long enough to receive ASCT. Nonetheless the dismal outcomes of those patients not transplanted reinforce the importance of effective prophylaxis (Cheah et al, 2014; Cheah & Seymour, 2015; Ferreri et al, 2015b) and the development of new therapeutic options for patients unable to tolerate, or who are unresponsive to, intensive chemotherapeutics strategies.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Study concept: JFS, CYC. Data collection: CYC, MG. Data analysis and creation of figures and tables: CYC. Writing, critical revision and approval of final version: all authors.