British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of people with rosacea 2021*

This is a guideline prepared for the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) Clinical Standards Unit, which includes the Therapy & Guidelines Subcommittee. Members of the Clinical Standards Unit that have been involved are: N.J. Levell, B. McDonald, P. Laws, S.L. Chua, A. Daunton, H. Frow, I. Nasr, M. Hashme (Information Scientist), L.S. Exton (Senior BAD Guideline Research Fellow), L. Manounah (BAD Guideline Research Fellow) and M.F. Mohd Mustapa (Director of Clinical Standards).

Plain language summary available online

Abstract

Linked Comment: J.S.S. Ho and Y. Asai. Br J Dermatol 2021; 185:689–690.

Plain language summary available online

1 Purpose and scope

The overall objective of the guideline is to provide up-to-date, evidence-based recommendations for the management of rosacea. The document aims to: (i) offer an appraisal of all relevant literature up to February 2020 focusing on any key developments; (ii) address important, practical clinical questions relating to the primary guideline objective; and (iii) provide guideline recommendations and, if appropriate, research recommendations.

The guideline is presented as a detailed review with highlighted recommendations for practical use in primary care and in the clinic, in addition to an updated Patient Information Leaflet [available on the British Association of Dermatologists’ (BAD) website: www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/a-z-conditions-treatments/].

1.1 Exclusions

This guideline does not cover the diagnosis of rosacea. The evidence supporting the recommendations does not include evidence that is specific to children.

2 Methodology

This set of guidelines has been developed using the BAD’s recommended methodology,1 with reference to the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument (www.agreetrust.org)2 and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation [GRADE; Appendix L (see Supporting Information)].3 Recommendations were developed for implementation in the UK National Health Service (NHS).

The guideline development group (GDG), which consisted of consultant dermatologists, a consultant ophthalmologist, patient representatives and a technical team (consisting of a guideline research fellow and project manager who provided methodological and technical support), established several clinical questions pertinent to the scope of the guideline and a set of outcome measures of importance to patients, ranked by the patient representatives according to the GRADE methodology [section 2.1 and Appendix A (see Supporting Information)].

A systematic literature search of PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane databases was conducted to identify key articles on rosacea up to February 2020; search terms and strategies are detailed in the supporting information (Appendix M; see Supporting Information). Additional references relevant to the topic were also isolated from citations in reviewed literature. Data extraction and critical appraisal, data synthesis, evidence summaries, lists of excluded studies and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) diagram were prepared by the technical team. Evidence from included studies was graded according to the GRADE system (high, moderate, low or very-low certainty). Recommendations are based on evidence drawn from systematic reviews of the literature pertaining to the clinical questions identified, following discussions with the entire GDG, and factoring in all items that would affect the strength of the evidence according to the GRADE approach (i.e. balance between desirable and undesirable effects, certainty of evidence, patient values and preference, and resource allocation). All GDG members contributed towards drafting and/reviewing the narratives and supporting information.

The summary of findings with forest plots (Appendix B; see Supporting Information), tables Linking the Evidence To the Recommendations [LETR; Appendix C (see Supporting Information)], GRADE evidence profiles indicating the certainty of evidence (Appendix D; see Supporting Information), summary of included studies (Appendix E see Supporting Information), narrative findings from comparative without data in an extractable format (Appendix F; see Supporting Information), narrative findings from within-patient studies (Appendix G; see Supporting Information), narrative findings from non-comparative studies (Appendix H; see Supporting Information), critical appraisal of the included systematic reviews (Appendix I; see Supporting Information), PRISMA flow diagram (Appendix J; see Supporting Information) and list of excluded studies (Appendix K; see Supporting Information) are detailed in the Supporting Information. The strength of recommendation is expressed by the wording and symbols shown in Table 1.

| Strength | Wording | Symbols | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong recommendation for the use of an intervention | ‘Offer’ (or similar, e.g. ‘use’, ‘provide’, ‘take’, ‘investigate’, etc.) | ↑↑ | Benefits of the intervention outweigh the risks; most patients would choose the intervention, while only a small proportion would not; for clinicians, most of their patients would receive the intervention; for policy makers, it would be a useful performance indicator |

| Weak recommendation for the use of an intervention | ‘Consider’ | ↑ | Risks and benefits of the intervention are finely balanced; most patients would choose the intervention but many would not; clinicians would need to consider the pros and cons for the patient in the context of the evidence; for policy makers it would be a poor performance indicator where variability in practice is expected |

| No recommendation | Θ | Insufficient evidence to support any recommendation | |

| Strong recommendation against the use of an intervention | ‘Do not offer’ | ↓↓ | Risks of the intervention outweigh the benefits; most patients would not choose the intervention, while only a small proportion would; for clinicians, most of their patients would not receive the intervention |

2.1 Clinical questions and outcomes

The GDG established several clinical questions pertinent to the scope of the guideline. See Appendix A (Supporting Information) for the full review protocol. The GDG also established two sets of outcome measures of importance to patients: one set for topical and systemic treatments; and one for procedural therapies [light, laser and intense pulsed light (IPL)], which were agreed and ranked by the patient representatives according to the GRADE methodology.4 Outcomes ranked 7, 8 and 9 are critical for decision-making; those ranked 4, 5 and 6 are important but not critical for decision-making; and those ranked 3, 2 and 1 are least important for decision-making.

Systematic review question 1: topical therapies

In people with rosacea what is the clinical effectiveness and safety of topical therapies, compared to each other or placebo?

|

Critical Objective response to treatment scoring systems |

|

| • Reduction in lesion counts | 8 |

| • Reduction in erythema | 8 |

| • Improvement in quality of life (QoL) | 7 |

| • Adverse events and tolerability | 7 |

| Important | |

| • Physician Global Assessment (PGA) | 6 |

| • Relapse/recurrence | 6 |

| • Patient global assessment | 6 |

| • Reduction in flushing | 6 |

Systematic review question 2: systemic therapies

In people with rosacea what is the clinical effectiveness and safety of systemic therapies, compared to topicals, each other or placebo?

|

Critical Objective response to treatment scoring systems |

|

| • Reduction in lesion counts | 8 |

| • Reduction in erythema | 8 |

| • Improvement in QoL | 7 |

| • Adverse events and tolerability | 7 |

| Important | |

| • PGA | 6 |

| • Relapse/recurrence | 6 |

| • Patient global assessment | 6 |

| • Reduction in flushing | 6 |

Systematic review question 3: procedural therapies

In people with rosacea what is the clinical effectiveness and safety of light, laser and IPL treatments?

|

Critical Objective response to treatment scoring systems |

|

| • Reduction in erythema | 8 |

| • Reduction in telangiectasia | 8 |

| • Improvement in QoL | 7 |

| • Adverse events and tolerability | 7 |

| Important | |

| • PGA | 6 |

| • Patient global assessment | 6 |

| • Relapse/recurrence | 6 |

| • Reduction in flushing | 6 |

3 Summary of recommendations

The following recommendations and ratings were agreed upon unanimously by the core members of the GDG and patient representatives. For further information on the wording used for recommendations and strength of recommendation ratings, see section 2.0. The GDG is aware of the lack of high-certainty evidence for some of these recommendations, therefore strong recommendations, marked with an asterisk (*), are based on available evidence, as well as consensus within the GDG and specialist experience. Good practice point (GPP) recommendations are derived from informal consensus.

General recommendations

R1 (GPP) Advise people with rosacea to limit exposure to known aggravating factors such as alcohol, sun exposure, hot drinks and spicy food.

R2 (GPP) Provide a patient information leaflet (www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/a-z-conditions-treatments/) to people with rosacea.

R3 (GPP) When characterizing the clinical subtypes and symptoms of rosacea, classify the patient according to the phenotypes identified by Gallo et al.5 This approach encompasses the objective clinical signs and the subjective symptoms experienced by the patient with rosacea. Diagnostic phenotypes include characteristic fixed centrofacial erythema or phymatous changes. Other features include flushing, papules or pustules, telangiectasia, ocular changes, burning or stinging sensations, oedema and dryness.

R4 (GPP) Take into account the older classification system for rosacea, which was based on clinical signs: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous or ocular. Characterize the clinical subtypes and symptoms of rosacea affecting the person according to these clinical signs.

R5 (GPP) Whenever possible, avoid long-term use of oral antibiotics in people with rosacea (i.e. antibiotic stewardship). The optimal duration of antibiotic therapy is not known. In acne, a lack of response after 2–3 months of antibiotic therapy is usually regarded as treatment failure, and a similar duration to establish benefit may be appropriate in rosacea. When antibiotics are working, the pros and cons of longer-term treatment need to be evaluated carefully.

R6 (GPP) Advise that some people with rosacea find it beneficial to wash their skin with emollients, moisturize regularly and use appropriate sun protection. Soaps and washing products that contain detergent are irritant in some people and should be avoided if they worsen the symptoms.

R7 (GPP) Consider skin camouflage in people with rosacea ‘whose main clinical feature is’ OR who are ‘presenting with’ intractable erythema.

R8 (GPP) Consider the need for psychological support or psychiatric interventions in people with rosacea who experience anxiety or depression. Initial assessment in primary care is often appropriate.

Topical therapies

R9 (↑↑) Offer either ivermectin, metronidazole or azelaic acid as first-line topical treatment options to people with papulopustular rosacea. Discuss the potential for irritancy of different products and formulations prior to prescribing the topical agent.

R10 (↑) Consider topical minocycline foam in people with papulopustular rosacea (minocycline foam is currently not available in the UK).

R11 (↑) Consider topical brimonidine in people with rosacea where the main presenting feature is facial erythema. Warn patients that there are reports that redness may flare after discontinuation of treatment.

R12 (↑) Consider topical oxymetazoline in people with rosacea where the main presenting feature is facial erythema. Warn patients that there are reports that redness may flare after discontinuation of treatment (oxymetazoline is currently not available in the UK).

Systemic therapies

R13 (↑↑) Offer* an oral antibiotic as a first-line treatment option for more severe papulopustular rosacea. Options (in alphabetical order) include azithromycin, clarithromycin, doxycycline 40 mg (modified release) daily, doxycycline 100 mg daily, erythromycin, lymecycline and oxytetracycline. These antibiotics (especially tetracyclines) are considered safe and have been prescribed for rosacea for decades. There is insufficient evidence to establish the superiority of one over another, especially in the absence of head-to-head trials or a network meta-analysis. Currently, only the modified-release formulation of doxycycline is licensed specifically for papulopustular rosacea in the UK.

R14 (↑↑) Avoid minocycline in people with rosacea due to potential side-effects, unless there are no other treatment options.

R15 (↑) Consider intermittent courses of low-dose isotretinoin (e.g. 0·25 mg kg–1) in people with persistent and severe rosacea. Discuss the potential side-effects and teratogenicity.

R16 (↑) Consider oral propranolol in people with rosacea where the main presenting feature is transient facial erythema (flushing).

Procedural therapies

R17 (↑) Consider pulsed dye laser, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser or intense pulsed light in people with rosacea where the main presenting feature is persistent facial erythema. An appropriately qualified laser practitioner should be consulted to ensure safe and high-quality practice.

R18 (↑) Consider nasal debulking by laser ablation or surgical intervention (dependent on local expertise) in people with significant rhinophyma.

Ocular therapies

R19 (↑↑) Advise* people with ocular rosacea to minimize exposure to aggravating factors such as air conditioning, excessive central heating, smoky atmospheres and periocular cosmetics.

R20 (↑↑) Identify* and modify/eliminate systemic medications that could be triggering eye dryness in people with ocular rosacea (e.g. antidepressants and anxiolytics).

R21 (↑↑) Offer* warm compresses using proprietary lid-warming devices and lid hygiene with homemade bicarbonate solution or commercially available lid wipes.

R22 (↑↑) Offer* over-the-counter ocular lubricants or liposomal sprays to alleviate symptoms in people with ocular rosacea, ensuring preservative-free preparations are used if using > 6 times daily. Increasing humidity using humidifiers can help to reduce tear evaporation.

R23 (↑↑) Refer* people with ocular rosacea to an ophthalmologist if they are (i) experiencing eye discomfort, sticky eye discharge persisting for > 12 months despite frequent (> 6 times daily) topical lubricant use and adequate lid hygiene; or (ii) experiencing symptoms such as reduced vision, pain on eye movement and pain that keeps the patient awake at night.

Summary of future research recommendations

The following list outlines future research recommendations (FRRs).

FRR1 A prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the effect of topical ivermectin on ocular rosacea.

FRR2 A prospective RCT investigating various interventions (topical/systemic/procedural) for transient erythema (flushing).

FRR3 A study investigating the psychological impact of rhinophyma, the effect of treatment and the optimal choice of surgical or laser treatments.

FRR4 A study investigating other acaricidal drugs currently used in veterinary practice, such as moxidectin and afoxolaner against Demodex.

FRR5 A cost-effectiveness analysis of treatments for people with rosacea within a UK setting.

FRR6 Investigations of the aetiology, pathophysiology and psychological issues of rosacea, and treatment of the sensory symptoms of rosacea, sometimes referred to as neurogenic rosacea.

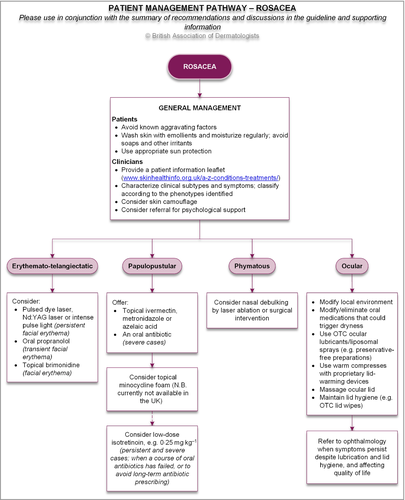

4 Algorithm

The recommendations, discussions in the LETR (Appendix C; see supporting information) and consensus specialist experience were used to inform the algorithm/pathway of care (Figure 1).

5 Background

5.1 Definition

Rosacea is a chronic disorder that predominantly affects the central areas of the face (nose, forehead, cheeks and chin). It is characterized by frequent flushing, persistent erythema and telangiectasia, and episodes of inflammation during which swelling, papules and pustules are evident. These symptoms are frequently accompanied by periocular inflammation and are sometimes associated with the later development of cutaneous swellings known as phymas.

5.2 Classification

- 1. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (vascular rosacea) In these cases, the predominant features are vascular (flushing, erythema and telangiectasia). Flushing is often noticed first and progresses gradually to persisting erythema and increasingly prominent telangiectasia. Factors that trigger flushing include emotion and stress,6 hot drinks,7 alcohol and other vasodilating drugs,8 and spicy food. The flushing and erythema are often accompanied by a burning sensation.9

- 2. Papulopustular rosacea (inflammatory rosacea) In these cases, the predominant features are inflammatory lesions (eruptions of papules and pustules). In contrast to acne, the lesions are usually painless, not consistently associated with hair follicles and not accompanied by comedones.

- 3. Ocular rosacea The predominant features of ocular rosacea include blepharitis, episcleritis, meibomian gland dysfunction, conjunctival scarring and corneal vascularization. Initially, there is a sensation of grittiness, burning or irritability of the eyes, accompanied by visible reddening of the eyelid margins and conjunctiva. The blepharoconjunctivitis is associated with a predominantly evaporative dry eye accompanied by aqueous deficiency, which results in an unstable tear film and a static or slowly progressive cicatrising conjunctivitis.10, 11 Ocular rosacea may be seen in isolation or occur before the onset of cutaneous features, especially in children.12 The condition may be unilateral or asymmetrical.12

- 4. Phymatous rosacea (mainly rhinophyma) This most frequently manifests as rhinophyma, a bulbous, rugose, soft-tissue swelling of the nose, although similar lesions occur less often in other facial locations including the ears (otophyma), forehead (metophyma) and chin (gnathophyma).

5.3 Epidemiology

Rosacea is a very common disease. It is predominantly a disease of young-to-middle-aged adults but is seen in patients of all ages, including, occasionally, in children. Estimates of prevalence vary considerably, but this is certainly a very common skin disease, estimated in 2018 to affect 5·5% of the global adult population.13 Women are more commonly affected than men, especially within the age range of 36–50 years. It is considered more common in individuals with less deeply pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III) than in those with more deeply pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), although it does occur in all skin types. The development of rhinophyma is more common in men. Symptoms of ocular rosacea are also common, although these are also often encountered in patients without other features of the disease, and as the symptoms in these cases are indistinguishable from those of ‘ocular rosacea’, it is probably impossible to ascertain the prevalence of the latter as a distinct entity.

5.4 Aetiology and pathogenesis

The cause, or causes, of rosacea remain uncertain, and both aetiology and pathogenesis seem likely to differ between the various categories.

It has been proposed that damage to dermal connective tissue, often caused by solar irradiation, may be the initiating event.14 This may result in dysfunction of the unsupported facial blood vessels with consequent endothelial damage, leakage, oedema and inflammation. Others have argued for a central role of abnormal vascular reactivity.15

It has also been proposed that lowered neural thresholds for reaction to noxious stimuli may result in neurogenic inflammation.9 Sensitivity to noxious stimuli, including heat, is increased in involved skin, regardless of whether vascular or inflammatory features predominate.9 This may explain the burning sensation frequently reported by patients with rosacea.

Changes in redox status, with reduced levels of superoxide dismutase have been observed in the skin in cases of inflammatory rosacea.16

Abnormally high levels of the endogenous antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin have been demonstrated in the facial skin of patients with rosacea.17Cathelicidin and related peptides trigger inflammation by promoting leucocyte chemotaxis and angiogenesis. Elevated levels of cathelicidin may be a secondary phenomenon, perhaps related to the presence of Demodex spp. or microorganisms in the skin. Upregulation of various elements of the innate skin immune system such as Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), which is an intracellular sensor that detects a broad range of microbial motifs, endogenous danger signals and environmental irritants, have been reported.18 Transient vanilloid receptor potential ion channel 1 (TRVP1) has a key role in temperature perception and is significantly overexpressed in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.19

Because there is usually no associated sweating, it has been argued that flushing in rosacea is mediated by released vasoactive substances rather than by a neural mechanism.20 Numerous possible vasoactive mediators have been proposed, but none has yet been firmly and consistently linked to the pathogenesis of rosacea.

Rosacea has often been linked with gastrointestinal symptomatology, although there is no conclusive evidence to support this. A possible role for Helicobacter pylori, infection of the gastric mucosa has been the subject of particular controversy, but in controlled studies prevalence rates have sometimes been similar to controls.21-24 The infection may be more prevalent in patients with papulopustular rosacea than those with erythematotelangiectatic disease.25 Certain chemicals found in common foods have been shown to stimulate sensory nerves. These include capsaicin (chilli) and resveratrol (a phenol found in red wine).26

A potential role has often been proposed for the follicle mites Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis in the pathogenesis of rosacea. Infestation with these mites is extremely common in the general population, reaching up to 100% of patients in some studies.25 Eruptions strongly resembling rosacea and associated with the presence of large numbers of D. folliculorum have been reported under the title of ‘rosacea-like demodicosis’. These cases have improved following treatment to eradicate the mite. Papulopustular rosacea has also been demonstrated to respond to this therapeutic approach.27 It is well established that there are increased numbers of D. folliculorum in the facial skin of patients with rosacea relative to controls.28-34 Demodex mites have also been histologically demonstrated in the dermis associated with an inflammatory response and undergoing phagocytosis by multinucleate giant cells. This phenomenon has been observed both in localized and more widespread facial eruptions resembling rosacea.35, 36 Furthermore, D. brevis is often present in the eyelid in hair follicles, eyelash follicles and meibomian glands,37, 38and is often reported in association with periocular pathology, including blepharitis and meibomianitis.39-41 These observations would suggest that the presence of Demodex mites might also play a role in some of the ophthalmic features of rosacea. The mites are associated with bacteria, which may also provoke an inflammatory response.

5.5 Impact on quality of life

Rosacea is a facial dermatosis and therefore easily visible. It can cause significant embarrassment and handicap to those who suffer from it. This impact has been quantified in a limited and heterogeneous range of studies. A 2014 review identified 12 studies in which the effect of rosacea on QoL was evaluated using validated instruments. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most frequently used instrument (in seven of the studies identified). DLQI scores ranged from 4·1 to 17·3, depending substantially on the population studied, with the highest scores being recorded in a study examining only severe cases.42 Another review that year found a similarly wide range of reported severity of impairment, with DLQI scores in rosacea ranging from 2 to 17·7.43 In a 2019 study of the impact of facial erythema, the mean (SD) DLQI score was 5·2 (6·0), and the impairment in QoL was strongly correlated with the severity of the centrofacial erythema.44 When compared with vitiligo, the mean DLQI score was 4·3 in patients with rosacea, and 7 in those with vitiligo. Severe QoL impairments (DLQI > 10), were less frequent (11·0%) than in vitiligo (24·6%).45

5.6 Natural history

Rosacea usually follows a fluctuating course. The eventual duration and outcomes are variable, and there is a paucity of published data. In a survey of 92 patients ≥ 10 years after a diagnosis of rosacea, 48 responded and 25 still had active disease, while 23 had cleared.46 In patients in whom the rosacea had resolved, the duration of the disease had ranged from 1 to 25 years.

Treatment of rosacea can effectively suppress the symptoms and signs of the disease, but there is no evidence that this is curative. In a follow-up study of 70 patients after 6 months of treatment with tetracycline, two-thirds had relapsed after a mean follow-up period of 2·6 years.47

5.7 Differential diagnosis

Acne vulgaris and rosacea are quite distinct diseases, although there are occasional patients in whom the distinction is difficult and, as both conditions are very common, it is to be expected that, by chance, both will often occur in the same patient. Acne vulgaris affects a younger age group and often has an extensive distribution over the face, neck and trunk, whereas extrafacial rosacea is rare. Typical acne vulgaris lacks the redness, telangiectasia and flushing of rosacea, while rosacea lacks the comedones and seborrhoea characteristic of acne vulgaris.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is often observed in association with rosacea and is therefore a potential cause of confusion, especially when the features of one disease predominate at one consultation and features of the other at the next. However, the typical pattern of seborrhoeic dermatitis differs markedly from rosacea. The former, but not the latter, characteristically involves the scalp, the retroauricular area, the eyelids and the nasolabial folds. Scaling is not normally a feature of rosacea but is the rule in seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Lupus erythematosus is an occasional cause of concern. Discoid lupus typically causes scarring, scaling and follicular plugging, which are not features of rosacea. However, patients are often referred to the dermatology clinic with a ‘butterfly’ erythema and a tentative diagnosis of systemic lupus. The latter is not pustular and is usually associated with systemic symptoms. In some cases, lupus serology and a skin biopsy for histological and immunofluorescent examination may be necessary.

Carcinoid syndrome is another cause of flushing often diagnosed after a significant delay from the onset of symptoms, and may initially be mistaken for rosacea. Atypical (prolonged, generalized or severe) flushing, or the presence of additional symptoms (sweating, bronchospasm, abdominal pain, diarrhoea) should prompt measurement of urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and further investigation if suspicion persists.

Nasal sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) superficially resembles rhinophyma. However, sarcoidosis often affects the nasal septum (causing nasal obstruction). The surface of the thickened nose in lupus pernio, although telangiectatic, is generally smooth, lacking the rugose peau d’orange surface that characterizes rhinophyma. Patients with lupus pernio almost invariably have evidence of multisystem disease.

5.8 Complications

Lymphoedema is a relatively rare complication of rosacea that can develop over the face and ears. In time, this may develop into a coarsening of the features known as leonine facies. A characteristic pattern of lymphoedema of the upper half of the face developing as a complication of chronic rosacea has been termed chronic upper facial erythematous oedema or Morbihan disease. The orbital skin is often affected, resulting in severe eyelid swelling and sometimes ectropion.

Malignancy, most frequently basal cell carcinoma, may be seen as a complication of rhinophyma. This can be difficult to diagnose owing to the phymatous distortion of normal skin contours, so it is important to be alert to this risk.

5.9 Facial dermatoses possibly related to rosacea

Perioral dermatitis (periorificial dermatitis) is sometimes regarded as a variant of rosacea. It presents as a persistent erythematous eruption of tiny papules and papulopustules that appears abruptly in the nasolabial areas and spreads rapidly to the perioral zone, sparing the lip margins. Occasionally, it may spread to the forehead, eyelids and glabella. Pruritus, burning and soreness are prominent symptoms. The lesions consist of monomorphic small papules and pustules occurring against a background of redness and variable scaling. The papules may occur in recurrent crops and are usually less substantial than those of rosacea. A similar eruption involving the eyelids and periorbital skin has been termed periocular dermatitis. It almost entirely affects young adult females, the age range tending to be somewhat younger than that of rosacea, and occurrence in childhood more frequent. Topical corticosteroid therapy is known to be an important aetiological factor. Occasionally, this can result from inadvertent transfer during topical corticosteroid treatment to other regions such as the hands. The use of inhaled corticosteroids for treating asthma, particularly from nebulizers, may also cause perioral dermatitis. Periocular dermatitis may be caused by corticosteroid eye ointment.48 A variety of primary irritant and allergic contact factors and cosmetic products have been proposed to play a role, but this has not been substantiated.49 A high prevalence of atopy has been reported in patients with perioral dermatitis.50 Perioral dermatitis tends to resolve if exposure to topical corticosteroid stops, although this may take some weeks or months. Less often, the condition may persist, continuously or intermittently.

Acne agminata (lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, acnitis and facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution [FIGURE]) is seen mainly in adolescents and young adults of either sex. It presents as multiple, monomorphic, symmetrical, reddish-brown papules on the chin, forehead, cheeks and eyelids.51 The lesions may cluster around the mouth or on the eyelids or eyebrows so that the term ‘agminata’ is appropriate, although – paradoxically – in many cases, the lesions are widely disseminated around the face and the term ‘disseminatus’ seems more applicable. Diascopy of larger lesions often reveals an apple jelly nodule-like appearance, indicating their granulomatous histology. This eruption tends to be self-limiting, resolving completely over a few months or up to 2 years. In some cases, there is scarring. The clinical picture in classical cases is distinctive and does not closely resemble rosacea.

The aetiology remains unknown. It has been considered by some to be a variant of rosacea. While the distribution of lesions is similar, the natural history and the tendency to affect males and females approximately equally, argue against this being a form of rosacea. It can be difficult to distinguish from micropapular sarcoidosis.

Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption [FACE], Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis, granulomatous periorificial dermatitis and sarcoid-like granulomatous dermatitis) is seen in prepubertal children and may represent a juvenile form of perioral dermatitis or of acne agminata. It is considered relatively common in Afro-Caribbean children.52

This is a papular eruption generally confined to the face, with lesions clustering around the mouth, eyes, nose and ears.53, 54 In contrast to perioral dermatitis it does not spare the narrow zone bordering the lips, and pustules are not seen. The histology has been variously described as showing nonspecific inflammation with hyperkeratosis or, more often, as granulomatous, with the inflammatory changes often, but not invariably, being perifollicular. Blepharitis has occasionally been present.

Complete resolution usually occurs after a few months – either spontaneously or in response to treatment. In some cases, small, pitted scars have been reported.

Pyoderma faciale (rosacea conglobata, rosacea fulminans) is a florid eruption of pustules and cystic swellings that may be interconnected by sinuses, confined to the face, with an absence of comedones.55, 56The latter two features distinguish this entity from acne conglobata. However, it remains possible that this is an unusual variant of acne vulgaris. This is a distressing disease, often followed by severe scarring. Pyoderma faciale mainly affects adults, and most frequently females (in contrast to acne conglobata). There is often no preceding history of acne or rosacea. It is usually a fulminant eruption (rosacea fulminans). Marked erythema and oedema are usually present. Some cases have developed during pregnancy, suggesting that hormonal factors may play a role. Occasional cases may arise as a side-effect of medication. Culture of the purulent discharge or needle aspiration may be sterile or may yield a growth of commensal organisms, including Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes. This investigation can be helpful in excluding Gram-negative infection. Significant scarring develops in many cases.

Steroid rosacea is the term used for the induction of symptoms closely resembling erythematotelangiectatic rosacea and/or inflammatory rosacea by the application of topical corticosteroids.57 This is usually associated with the use of potent and very potent corticosteroids, although less potent compounds can occasionally cause similar problems. This entity is clearly associated with the use of topical corticosteroids, and it is not clear whether there are mechanisms in the pathogenesis shared with rosacea. Topical corticosteroids may also induce features of acne vulgaris, and these may coexist in the same patients.

Facial dysaesthesia is a clinical presentation in which sensory disturbance predominates and is often out of proportion to any visible abnormality.58 The most common complaint is a severe facial burning sensation, usually occurring intermittently, and sometimes triggered by contact, temperature changes or particular foods. Facial hypersensitivity is often a feature of rosacea, but in some cases appears to occur with minimal or no other features of that disease. These symptoms are sometimes referred to as neurogenic rosacea.

6 Recommended audit points

- 1. A trial of topical ivermectin in those on long-term antibiotics?

- 2. Advice to avoid aggravating factors such as alcohol, sun exposure, hot drinks or spicy food?

- 3. Discussion of the pros and cons of intermittent low-dose isotretinoin as an alternative to long-term antibiotics, in whom there is no contraindication?

- 4. Offering of propranolol in those with symptomatic flushing, in whom there is no contraindication?

The audit recommendation of 20 cases per department is to reduce variation in the results due to a single patient and allow benchmarking between different units. However, departments unable to achieve this recommendation may choose to audit all cases seen in the preceding 12 months (Appendix N; see Supporting Information).

7 Stakeholder involvement and peer review

The draft document and supporting information was made available to the BAD membership, British Dermatological Nursing Group, Primary Care Dermatological Society, British Society for Medical Dermatology, British Society for Dermatological Surgery and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists for comments, which were actively considered by the GDG. Following further review, the finalized version was sent for peer review by the Clinical Standards Unit of the BAD (made up of the Therapy & Guidelines Subcommittee) prior to submission for publication.

8 Limitations of the guideline

This document has been prepared on behalf of the BAD and is based on the best data available when the document was prepared. It is recognized that under certain conditions it may be necessary to deviate from the guidelines and that the results of future studies may require some of the recommendations herein to be changed. Additionally, it is acknowledged that limited cost-effectiveness data in the context of the UK healthcare setting may affect the availability of a given therapy within the NHS, despite evidence of efficacy. Failure to adhere to these guidelines should not necessarily be considered negligent, nor should adherence to these recommendations constitute a defence against a claim of negligence. Limiting the systematic review to English language references was a pragmatic decision, but the authors recognize that this may exclude some important information published in other languages.

9 Plans for guideline revision

The proposed revision date for this set of recommendations is scheduled for 2026; where necessary, important interim changes will be updated on the BAD website.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to patient representatives Mr Ian Porter and Dr John Berth-Jones for their input in formulating the clinical questions, ranking of the outcomes, reviewing of the evidence and subsequent draft guideline. We are also very grateful to Drs Edward Seaton and Iaisha Ali, and Professors Alison Layton, Frank Powell and Malcolm Greaves (consultant dermatologists), and Mr Jeremy Prydal (consultant ophthalmologist) for their involvement during the early stages of the guideline development process, and to Miss Alina Constantin (BAD Guideline Research Fellow) for assisting with the final stages, as well as all those who commented on the draft during the consultation period.

Author Contribution

Philip J Hampton: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Supervision (lead); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (lead); Writing-review & editing (lead). John Berth-Jones: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Emilia Duarte Williamson : Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Rod Hay: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Tabi Leslie: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Ian Porter : Conceptualization (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-review & editing (supporting). Saaeha Rauz: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Daron Seukeran : Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Remus T Winn : Data curation (equal); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Maria Hashme: Data curation (equal). Lesley S Exton: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Methodology (supporting); Validation (equal); Visualization (supporting); Writing-review & editing (equal). M. Firouz Mohd Mustapa: Conceptualization (lead); Methodology (lead); Project administration (lead); Validation (equal); Writing-original draft (equal); Writing-review & editing (equal). Lina Manounah: Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (lead); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (lead); Writing-original draft (lead); Writing-review & editing (equal).