Consumer acceptance of patient-performed mobile teledermoscopy for the early detection of melanoma†

Summary

Background

Mobile teledermoscopy allows consumers to send images of skin lesions to a teledermatologist for remote diagnosis. Currently, technology acceptance of mobile teledermoscopy by people at high risk of melanoma is unknown.

Objectives

We aimed to determine the acceptance of mobile teledermoscopy by consumers based on perceived usefulness, ease of use, compatibility, attitude/intention, subjective norms, facilitators and trust before use. Consumer satisfaction was explored after use.

Methods

Consumers aged 50–64 years at high risk of melanoma (fair skin or previous skin cancer) were recruited from a population-based cohort study and via media announcements in Brisbane, Australia in 2013. The participants completed a 27-item questionnaire preteledermoscopy modified from a technology acceptance model. The first 49 participants with a suitable smartphone then conducted mobile teledermoscopy in their homes for early detection of melanoma and were asked to rate their satisfaction.

Results

The preteledermoscopy questionnaire was completed by 228 participants. Most participants (87%) agreed that mobile teledermoscopy would improve their skin self-examination performance and 91% agreed that it would be in their best interest to use mobile teledermoscopy. However, nearly half of participants (45%) were unsure about whether they had complete trust in the telediagnosis. The participants who conducted mobile teledermoscopy (n = 49) reported that the dermatoscope was easy to use (94%) and motivated them to examine their skin more often (86%). However, 18% could not take photographs in hard-to-see areas and 35% required help to submit the photograph to the teledermatologist.

Conclusions

Mobile teledermoscopy consumer acceptance appears to be favourable. This new technology warrants further assessment for its utility in the early detection of melanoma or follow-up.

Dermatologists diagnose skin conditions, including melanoma, with excellent accuracy based on a visual inspection.1 Dermatology, therefore, is a medical specialty that is well suited to telemedicine. Teledermatology has been tested in the context of early detection, remote clinical diagnosis and patient triage for several dermatological conditions.2-4 Benefits of telemedicine include increased access to care, reduced waiting time, reduced travel, potential cost savings and efficient referral.5 Concerns about teledermatology include the lack of direct patient contact and insufficient follow-up.6 Teledermatology can be performed via live video communication between doctor and patient or via a ‘store-and-forward’ system.1 The latter allows for the electronic transmission of photographs of skin conditions to a dermatologist for diagnosis and management advice and is more easily organized owing to the time independence of the patient and the doctor. One application of teledermatology that is used for melanoma diagnosis is mobile teledermoscopy. Mobile teledermoscopy uses a dermatoscope attachment for a smartphone, which allows lesion magnification under light, and a specialized application (app) to simplify the workflow of sending images and clinical information.

As summarized in four reviews, store-and-forward teledermatology for skin cancer diagnosis has high diagnostic accuracy compared with face-to-face diagnosis.7-10 In one study on store-and-forward teledermoscopy, 955 lesions (from 690 patients) were diagnosed by two teledermatologists with an overall diagnostic accuracy rate of 94%.11

Previous studies have assessed satisfaction of teledermatology among general practitioners when used to obtain a second opinion from dermatologists.12-14 Patient satisfaction with teledermatology has been summarized in four reviews.6, 8, 10, 15 Patient satisfaction with store-and-forward teledermatology varied widely (42–93%)8 using a range of data collection instruments. Only one small pilot study16 focused on consumer-driven mobile teledermoscopy for early melanoma detection and participants found the dermatoscope easy to use.

The present study assessed the self-reported consumer technology acceptance of mobile teledermoscopy when used for early melanoma detection during skin self-examination (SSE). Technology acceptance refers to consumer attitudes towards mobile teledermoscopy and whether or not they would use it. Selected participants with a suitable smartphone trialled the dermatoscope at home and their satisfaction with mobile teledermoscopy was assessed both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Materials and methods

The ethics committees of the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and QIMR Berghofer Research Institute approved the study (QUT approval number 1200000553; QIMR approval number PI309). This research used data from the pre- and post-teledermoscopy surveys.

Preteledermoscopy survey

Potential participants aged 50–64 years were recruited through the QSkin Sun and Health Study (QSkin),17 a cohort study conducted in Queensland, Australia, to investigate skin cancer risk factors. QSkin enrolled 43 794 participants. Investigators selected a random sample of 500 QSkin participants to be invited to the current study who lived within the Brisbane area and met at least one criterion for having a high risk of melanoma. These included fair skin, light eye colour, numerous dysplastic naevi or history of skin cancer. Potential participants were sent an expression of interest letter asking whether they would agree to complete the preteledermoscopy survey. Of those, 261 participants and 59 volunteers (who joined the study after a media announcement and also met the inclusion criteria) received a consent form and survey (total n = 320). Overall, 230 of 320 participants (71·9%) completed the preteledermoscopy survey and returned it by mail.

Outcome measure preteledermoscopy

Orruno et al.13 tested a modified version of the technology acceptance model. Using the model, they developed a 33-item multidimensional questionnaire to assess general practitioners’ teledermatology acceptance. We adapted this questionnaire for consumer-driven mobile teledermoscopy and excluded eight items relating to physician practices and added two items that assessed trust. Five experts in melanoma research evaluated and approved of the instrument face validity. Cronbach's alpha for each of the seven domains was acceptably high (above recommended 0·70), except for the facilitators (0·68) and compatibility (0·48) domains, which was likely to be due to the small number of items in these domains (three and four, respectively). Higher Cronbach's alpha scores indicate that the items in a questionnaire measure the same construct.

The response options for the resulting 27-item survey ranged from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree), which were collapsed into the following three categories for reporting purposes: 3 = agree (agree/strongly agree), 2 = neutral and 1 = disagree (disagree/ strongly disagree). Questions were summarized in the following seven domains: perceived usefulness (five items), perceived ease of use (four items), attitude and intention (six items), compatibility (four items), facilitators (three items), subjective norms (three items) and trust (two items).

Post-teledermoscopy survey

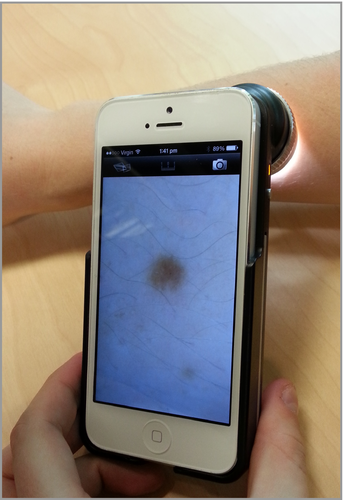

We assessed the diagnostic accuracy of teledermoscopy and satisfaction with patient-performed mobile teledermoscopy. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical results were previously reported.18 Briefly, among all participants who completed the preteledermoscopy survey (n = 230), the first 58 participants who expressed interest and had access to an iPhone were enrolled and mailed the dermatoscope (FotoFinder Systems GmbH, Bad Birnbach, Germany) (Fig. 1). They conducted one SSE using mobile teledermoscopy in their homes for early melanoma detection. The dermatoscope has both polarized and nonpolarized capabilities; participants were asked to use the nonpolarized option. Data are available for 49 participants. The 49 participants performed mobile teledermoscopy using a set of written instructions, including instructions on how to download the Handyscope app, how to use the dermatoscope to obtain and send dermoscopic images, and how to take a second clinical image to verify the anatomical location of the lesion. Participants were provided with the asymmetry and colour (AC) rule for identifying melanoma19 and asked to photograph spots they ‘did not like the look of’. The participants submitted their dermoscopic and anatomical images to the study researchers from their iPhone via the Handyscope app. Photographs were reviewed by the study dermatologist and the dermatology registrar. The participants were asked to return the dermatoscope and questionnaire via prepaid mail. Figure 2 displays participant recruitment and flow through the study.

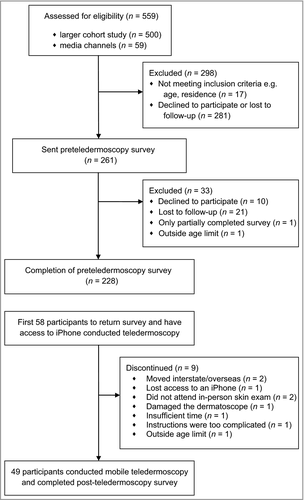

The participants whose differential telediagnosis included skin cancer were provided with their results via phone by the study dermatology registrar under the supervision of the same dermatologist who undertook the telediagnosis. The participants were referred to their regular general practitioner or dermatologist if excision was recommended. When the lesions were telediagnosed as likely benign, the participants were provided with their results at the follow-up in-person consultation by the dermatologist within 3 months of telediagnosis. The follow-up consultation was conducted to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the telediagnosis compared with an in-person clinical skin examination and the results have been previously reported.18 The participants were provided with a gift voucher (AUD$100) as reimbursement for their time, cost of the app and travel. The clinical outcomes were reported previously.12 The 49 participants who conducted mobile teledermoscopy submitted 309 lesions to the teledermatologist (median five photographs per person, range 0–21). Of the 309 lesions, all but two dermoscopic images, which were of poor quality, allowed telediagnosis. Participants demonstrated an 89% diagnostic agreement between telediagnosis and clinical diagnosis for consumer-submitted photographs of lesions overall, but lesion-based sensitivity (41%) was low owing to patients missing some lesions that were considered by the dermatologist to be worth photographing.18 Figure 3 displays a dermoscopic image captured by a participant.

Outcome measures post-teledermoscopy survey

The post-teledermoscopy survey assessed the participants’ satisfaction with mobile teledermoscopy and was completed by the 49 participants after using the dermatoscope at home. The questions were adapted from a previous study.16, 20 Forced-choice survey questions asked the participants to rate their confidence conducting SSE alone or with mobile teledermoscopy, whether they experienced any difficulties, whether they required help taking photographs and whether they would use mobile teledermoscopy in the future. The participants were asked one open-ended question about their opinions on conducting mobile teledermoscopy at home.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for demographic variables and mobile teledermoscopy acceptance and satisfaction questions. Fisher's exact tests were used to measure associations between participants’ skin cancer history and mole count with teledermoscopy acceptance. Internal consistency of the domains was calculated using Cronbach's alpha.

Results

Participant characteristics are described in Table 1. We excluded one participant with extensive missing data and one participant who was outside the age limit, leaving 228 evaluable participants. Both sexes were equally represented (51% female). Most participants were aged 50–54 years (47%) and had sun-sensitive phenotypic characteristics (blue/grey eye colour 48%, fair complexion 85%). Half of participants had a previously removed skin cancer and only one had used mobile teledermoscopy before. Overall, 92% of participants who completed the follow-up survey had an iPhone 4 or 5.

| Characteristic | Preteledermoscopy survey n (%) | Post-teledermoscopy n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | n = 228 | n = 49 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 111 (48·7) | 24 (49) |

| Female | 117 (51·3) | 25 (51) |

| Age | ||

| 50–54 | 108 (47·4) | 19 (39) |

| 55–59 | 78 (34·2) | 16 (33) |

| 60–64 | 42 (18·4) | 14 (29) |

| Educational attainmenta | ||

| Primary school or leaving certificate | 23 (10·1) | 4 (8) |

| High school or trade | 44 (19·3) | 8 (16) |

| University degree/diploma | 157 (68·9) | 36 (74) |

| Work | ||

| Full-time (including self-employed) | 134 (58·8) | 38 (78) |

| Part-time | 33 (14·5) | 3 (6) |

| Other/did not specify | 61 (26·7) | 8 (16) |

| Marital statusb | ||

| Living with partner | 185 (81·1) | 41 (84) |

| Living without partner | 42 (18·4) | 8 (16) |

| Previous skin cancer excised | ||

| Yes | 114 (50·0) | 24 (49) |

| No or unsure | 114 (50·0) | 25 (51) |

| Skin type | ||

| Fair | 193 (84·6) | 44 (90) |

| Medium | 32 (14·0) | 4 (8) |

| Dark | 3 (1·3) | 1 (2) |

| Moles larger than 2 mm on upper arm | ||

| 0 moles | 97 (42·5) | 18 (37) |

| 1–10 moles | 108 (47·4) | 24 (49) |

| 11+ moles | 23 (10·1) | 7 (14) |

| Eye colourc | ||

| Blue/grey | 110 (48·2) | 19 (39) |

| Green | 29 (12·7) | 6 (12) |

| Hazel/brown | 85 (37·3) | 24 (49) |

| Other (more than one colour) | 3 (1·3) | – |

- aFour missing education in preteledermoscopy survey, one missing education in post-teledermoscopy survey. bOne missing marital status in preteledermoscopy survey. cOne missing eye colour in preteledermoscopy survey.

Preteledermoscopy

Overall, 13 of 27 items (48%) were rated as ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ by 75% or more of the participants (Table 2). On average, the participants agreed (median = 3) with all items in the following domains: perceived ease of use, facilitators, subjective norms, attitude/intention and perceived usefulness. The participants reported neutral viewpoints (median = 2) when asked whether they would have ‘complete trust’ in the teledermatologist's telediagnosis, and were unsure whether mobile teledermoscopy ‘would fit in with their current habits’. When compared with participants without prior skin cancer, the participants who had a previous skin cancer removed were more likely to agree with the following items: ‘Mobile teledermoscopy will help to diagnose skin cancer quicker’ (80% compared with 69%, P = 0·01), ‘Diagnosis of a suspicious mole or spot made through mobile teledermoscopy would be clear and easily understandable’ (54% compared with 47%, P = 0·04) and ‘My doctor will welcome the fact that I use mobile teledermoscopy’ (61% compared with 51%, P = 0·04) (Table 2). There was no difference in teledermoscopy acceptance for participants who had one or more moles on their upper arm vs. those who did not have any moles (data not shown).

| Items | No personal skin cancer history | P-value | Cronbach's alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 228 | Skin cancer excised n (%) N = 114 | N = 114 | |||

| Perceived usefulness | |||||

| MTD will help me to examine my skin more rapidlya | 0·64 | 0·83 | |||

| Agree | 174 (76·3) | 94 (82·5) | 97 (85·1) | ||

| Unsure | 44 (19·3) | 15 (13·2) | 15 (13·2) | ||

| Disagree | 9 (3·9) | 5 (4·4) | 2 (1·8) | ||

| MTD will improve my skin self-examination performance | 0·99 | ||||

| Agree | 198 (86·8) | 99 (86·8) | 99 (86·8) | ||

| Unsure | 24 (10·5) | 12 (10·5) | 12 (10·5) | ||

| Disagree | 6 (2·6) | 3 (2·6) | 3 (2·6) | ||

| The use of MTD will improve the diagnosis of spots and moles on my skin that look suspicious | 0·09 | ||||

| Agree | 194 (85·1) | 93 (81·6) | 101 (88·6) | ||

| Unsure | 30 (13·2) | 17 (14·9) | 13 (11·4) | ||

| Disagree | 4 (1·8) | 4 (3·5) | – | ||

| MTD will help me save time | 0·91 | ||||

| Agree | 134 (58·8) | 68 (59·6) | 66 (57·9) | ||

| Unsure | 79 (34·6) | 38 (33·3) | 41 (36·0) | ||

| Disagree | 15 (6·6) | 8 (7·0) | 7 (6·1) | ||

| MTD will help to diagnose skin cancer quicker | 0·01 | ||||

| Agree | 170 (74·6) | 91 (79·8) | 79 (69·3) | ||

| Unsure | 55 (24·1) | 20 (17·5) | 35 (30·7) | ||

| Disagree | 3 (1·3) | 3 (2·6) | – | ||

| Perceived ease of use | 0·63 | 0·80 | |||

| It will be easy to perform MTD | |||||

| Agree | 149 (65·4) | 75 (65·8) | 74 (64·9) | ||

| Unsure | 77 (33·8) | 39 (24·2) | 38 (33·3) | ||

| Disagree | 2 (0·9) | – | 2 (1·8) | ||

| I will easily learn how to use MTD | 0·77 | ||||

| Agree | 197 (86·4) | 100 (87·7) | 97 (85·1) | ||

| Unsure | 28 (12·3) | 13 (11·4) | 15 (13·2) | ||

| Disagree | 3 (1·3) | 1 (0·9) | 2 (1·8) | ||

| Diagnosis of a suspicious mole or spot made through MTD would be clear and easily understandable | 0·04 | ||||

| Agree | 115 (50·4) | 61 (53·5) | 54 (47·4) | ||

| Unsure | 107 (46·9) | 53 (46·5) | 54 (47·4) | ||

| Disagree | 6 (2·6) | – | 6 (5·3) | ||

| I will find it easy to acquire the necessary skills to use MTD | 0·81 | ||||

| Agree | 194 (85·1) | 96 (84·2) | 98 (86·0) | ||

| Unsure | 29 (12·7) | 16 (14·0) | 13 (11·4) | ||

| Disagree | 5 (2·2) | 2 (1·8) | 3 (2·6) | ||

| Compatibility | |||||

| MTD will help me to examine my skin more thoroughly | 0·99 | 0·48 | |||

| Agree | 203 (89·0) | 101 (88·6) | 102 (89·5) | ||

| Unsure | 20 (8·8) | 10 (8·8) | 10 (8·8) | ||

| Disagree | 5 (2·2) | 3 (2·6) | 2 (1·8) | ||

| The use of MTD will involve major changes in my skin self-examination practice | 0·78 | ||||

| Agree | 156 (68·4) | 79 (69·3) | 77 (67·5) | ||

| Unsure | 50 (21·9) | 23 (20·2) | 27 (23·7) | ||

| Disagree | 22 (9·6) | 12 (10·5) | 10 (8·8) | ||

| The use of MTD fits with my current skin self-examination habits | 0·23 | ||||

| Agree | 154 (67·5) | 55 (48·2) | 44 (38·6) | ||

| Unsure | 43 (18·9) | 28 (24·6) | 39 (34·2) | ||

| Disagree | 31 (13·6) | 31 (27·2) | 31 (27·2) | ||

| The use of MTD may interfere with my usual skin self-examination | 0·31 | ||||

| Agree | 6 (2·6) | 3 (2·6) | 3 (2·6) | ||

| Unsure | 39 (17·1) | 15 (13·2) | 24 (21·1) | ||

| Disagree | 183 (80·3) | 96 (84·2) | 87 (76·3) | ||

| Intention and attitude | |||||

| I will use MTD when it is offered to me | 0·88 | 0·84 | |||

| Agree | 203 (89·0) | 103 (90·4) | 100 (87·7) | ||

| Unsure | 19 (8·3) | 8 (7·0) | 11 (9·6) | ||

| Disagree | 6 (2·6) | 3 (2·6) | 3 (2·6) | ||

| I will use MTD routinely when I do skin self-examination in the future | 0·54 | ||||

| Agree | 168 (73·7) | 86 (75·4) | 82 (71·9) | ||

| Unsure | 52 (22·8) | 23 (20·2) | 29 (25·4) | ||

| Disagree | 8 (3·5) | 5 (4·4) | 3 (2·6) | ||

| I will use MTD if it will save me time | 0·52 | ||||

| Agree | 172 (75·4) | 88 (77·2) | 84 (73·7) | ||

| Unsure | 30 (13·2) | 12 (10·5) | 18 (15·8) | ||

| Disagree | 26 (11·4) | 14 (12·3) | 12 (10·5) | ||

| I will use MTD if it will save me money | 0·72 | ||||

| Agree | 154 (67·5) | 80 (70·2) | 74 (64·9) | ||

| Unsure | 43 (18·9) | 20 (17·5) | 23 (20·2) | ||

| Disagree | 31 (13·6) | 14 (12·3) | 17 (14·9) | ||

| In general, MTD will be useful to improve diagnosis of skin cancer | 0·30 | ||||

| Agree | 201 (88·2) | 104 (91·2) | 97 (85·1) | ||

| Unsure | 25 (11·0) | 9 (7·9) | 16 (14·0) | ||

| Disagree | 2 (0·9) | 1 (0·9) | 1 (0·9) | ||

| Participating in MTD will be in my best interests | 0·99 | ||||

| Agree | 208 (91·2) | 104 (91·2) | 104 (91·2) | ||

| Unsure | 18 (7·9) | 9 (7·9) | 9 (7·9) | ||

| Disagree | 2 (0·9) | 1 (0·9) | 1 (0·9) | ||

| Subjective norm | |||||

| Other health professionals (physicians, nurses, other specialists etc.) will welcome the fact that I use MTD | 0·81 | 0·77 | |||

| Agree | 120 (52·6) | 63 (55·3) | 57 (50·0) | ||

| Unsure | 104 (45·6) | 49 (43·0) | 55 (48·2) | ||

| Disagree | 4 (1·8) | 2 (1·8) | 2 (1·8) | ||

| Most of my friends or family will welcome the fact that I use MTD | 0·21 | ||||

| Agree | 154 (67·5) | 83 (72·8) | 71 (62·3) | ||

| Unsure | 65 (28·5) | 28 (24·6) | 37 (32·5) | ||

| Disagree | 9 (3·9) | 3 (2·6) | 6 (5·3) | ||

| My doctor will welcome the fact that I use MTD | 0·04 | ||||

| Agree | 170 (55·7) | 69 (60·5) | 58 (50·9) | ||

| Unsure | 55 (43·0) | 42 (36·8) | 56 (49·1) | ||

| Disagree | 3 (1·3) | 3 (2·6) | – | ||

| Trust | |||||

| I will have complete trust in the dermatologist's diagnosis based on a photo I e-mailed as part of MTD | 0·85 | 0·78 | |||

| Agree | 107 (46·9) | 63 (55·3) | 64 (56·1) | ||

| Unsure | 104 (45·6) | 41 (36·0) | 38 (33·3) | ||

| Disagree | 17 (7·5) | 10 (8·8) | 12 (10·5) | ||

| I will rely on the teledermatology process to supply accurate information about a mole or spot | 0·96 | ||||

| Agree | 127 (55·7) | 54 (47·4) | 53 (46·5) | ||

| Unsure | 79 (34·6) | 51 (44·7) | 53 (46·5) | ||

| Disagree | 22 (9·6) | 9 (7·9) | 8 (7·0) | ||

| Facilitator | |||||

| I will use MTD if I receive adequate training | 0·40 | 0·68 | |||

| Agree | 210 (91·1) | 106 (93·0) | 104 (91·2) | ||

| Unsure | 10 (4·4) | 3 (2·6) | 7 (6·1) | ||

| Disagree | 8 (3·5) | 5 (4·4) | 3 (2·6) | ||

| I will use MTD if I receive technical assistance when I need it | 0·88 | ||||

| Agree | 194 (85·1) | 96 (84·2) | 98 (86·0) | ||

| Unsure | 24 (10·5) | 12 (10·5) | 12 (10·5) | ||

| Disagree | 10 (4·4) | 6 (5·3) | 4 (3·5) | ||

| There are health professionals available who will help me with MTD | 0·99 | ||||

| Agree | 132 (57·9) | 66 (57·9) | 66 (57·9) | ||

| Unsure | 95 (41·7) | 48 (42·1) | 47 (41·2) | ||

| Disagree | 1 (0·4) | – | 1 (0·9) | ||

- MTD, mobile teledermoscopy. Data are provided as n (%). aOne participant missing; strongly agree and agree combined into a single agreement category; strongly disagree and disagree combined into a single disagreement category.

Post-teledermoscopy

Most participants who conducted mobile teledermoscopy (42 of 49; 86%) agreed that mobile teledermoscopy motivated them to conduct SSE regularly and also agreed that the dermatoscope was easy to use (46 of 49; 94%). On average, the participants were confident taking photographs with the dermatoscope (median = 8, scale 1–10 where 1 = not at all confident and 10 = highly confident; range 4–10). Most participants (38 of 49; 78%) wished to use mobile teledermoscopy again in the future.

Overall, 65% of participants (32 of 49) experienced no difficulties when conducting mobile teledermoscopy. Some barriers were reported by participants; nine of 49 (18%) could not take a photograph in a ‘hard-to-see’ body location and seven of 49 (14%) had difficulty submitting the photograph to the teledermatologist. Difficulties included not being able to connect to an internet account on their iPhone, sequencing or labelling of images and personalizing the app. A total of 35% of participants (17 of 49) required help from their partner, child, friend or study personnel when submitting photographs on their iPhone. Most participants (36 of 49; 74%) had assistance with taking photographs from either their partner, child or sibling. The majority of participants (37 of 49; 75%) did not experience any worry or distress waiting for their results; however, six of 49 participants felt anxious conducting mobile teledermoscopy. One participant had difficulty understanding the study instructions provided and two participants were unable to take clear photographs. Forty-one participants (84%) found the AC rule to be a good tool for finding moles to photograph, while six were unsure and two disagreed (Table 3).

| Items | N = 49 |

|---|---|

| Taking photographs with the dermatoscope attachment was easya | |

| Agree | 46 (94) |

| Unsure | 1 (2) |

| Disagree | – |

| Having the dermatoscope has motivated me to do skin examinations on myself more regularly | |

| Agree | 42 (86) |

| Unsure | 3 (6) |

| Disagree | 4 (8) |

| Conducting a whole body skin examination was easy | |

| Agree | 26 (53) |

| Unsure | 9 (18) |

| Disagree | 14 (28) |

| Would you wish to send photographs to a doctor to assist you in checking your own skin in the future? | |

| Yes | 38 (78) |

| Unsure | 4 (8) |

| No | 7 (14) |

| Did you experience any difficulties when photographing your moles or skin spots? | |

| Yes | 17 (35) |

| No | 32 (65) |

| If yes, what experiences did you find difficult? (Select all that apply) | |

| I could not understand the instructions | 1 (2) |

| I could not download the Handyscope FotoFinder app | – |

| I could not take a clear or close-up photograph of a particular mole or spot | 2 (4) |

| I could not photograph a particular mole or skin spot because it was in a hard-to-see location or angle | 9 (18) |

| I had difficulty personalizing the app functions (e.g. entering my study ID, sex, birth date) | 3 (6) |

| I had difficulty sending the e-mail to the study dermatologist | 7 (14) |

| Did you ask another person to help you photograph your moles or skin spots? | |

| Yes | 36 (74) |

| No | 13 (26) |

| By taking pictures of your spots or moles, did you feel distressed, anxious or worried about these spots or moles?a | |

| Yes | 6 (12) |

| Don't know | 4 (8) |

| No | 37 (76) |

| Did you find the AC Rule (asymmetry, colour) to be a good tool to guide you in finding spots or moles to photograph? | |

| Yes | 41 (83·7) |

| Don't know | 6 (12·2) |

| No | 2 (4·1) |

- Data are provided as n (%). aAnswer missing from two participants.

Open-ended responses

Overall, 17 participants responded to the open-ended question. Participants provided positive feedback that included the following comments: ‘Fascinating to see the skin close up. Every home should have one [dermatoscope]!’ and ‘A very worthwhile study. Would be handy to monitor changes yourself with a dermatoscope.’

The dermatoscope was a prompt for action. One participant commented: ‘Having an opportunity to use the dermatoscope reminded me of the importance of self-examination … as I had not been for my regular skin check-up with my dermatologist for 2 years in spite of my brother [being] diagnosed with a melanoma.’

Participants noted concerns, particularly about trust in the telediagnosis compared with in-person consultations and the need for training: ‘It was an initial good tool; however, I am not a specialist and so I will not feel happy until you provide me with a full skin exam, then I'll know if my skills are OK.’ Another participant responded: ‘Generally I feel that I would prefer to have a professional examine me for melanoma, but I can appreciate the value of the dermatoscope if I lived in a rural or remote region.’ Others commented: ‘The concept of self-diagnosis is excellent, given the immediacy of the possible response, but it is dependent on the competence of the individual.’ Another participant noted the difficulty of imaging numerous dysplastic naevi clustered together: ‘I have so many moles on my back it was hard to label which was which for this study.’

Discussion

We found that a high proportion of participants (38 of 49, 78%) would use mobile teledermoscopy again in the future after experiencing it in this study. Mobile teledermoscopy was well received and was reported to be an easy process to conduct, which reinforced the importance of SSE for early melanoma detection. In the preteledermoscopy questionnaire almost all participants agreed with the items in the domains perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, intention and attitude, facilitators and subjective norm, whereas trust and compatibility received some neutral ratings.

This study is unique in that (i) it uses mobile teledermoscopy, which involves a more intricate image acquisition process than teledermatology, allowing for higher image quality and (ii) it focuses on self-completed SSE in the home environment. In contrast, most previous research assessed satisfaction with store-and-forward teledermatology conducted in healthcare professional settings where nurses or general practitioners take the images.21-25 The preference for mobile teledermoscopy in this format varies. For example, in one study on store-and-forward teledermatology, participants did not express a clear preference for an in-person consultation method; 42% of participants agreed they would rather use teledermatology, 22% were unsure and 37% preferred in-person consultations.21 Collins et al.24 found no difference in satisfaction between in-person or mobile teledermoscopy consultation, as both groups were pleased with the service.

Only one small study previously assessed the feasibility of mobile teledermoscopy during a home SSE.16 Similar to the findings here, the 10 participants learned to use the technology with ease, but the study was limited by its very small sample size. Wu et al. assessed patient-performed mobile teledermoscopy for monitoring of skin lesions identified by a doctor during an in-person consultation.26 The doctor completed the imaging process at the initial consultation and 3–4 months later the patient completed the imaging process for the same lesion in the office setting. Most participants did not report any barriers to use, except the desire of patients to see a dermatologist in person.26 Trust in the telediagnosis is a potential barrier to use as expressed by some participants in the current study who would prefer an in-person consultation. The qualitative comments indicate that training for patients and reassurance that they had self-selected the correct lesions could improve trust in subsequent rounds. Most participants were satisfied with the AC rule in this research. However, in the qualitative comments some participants raised concerns about their own ability to find the most relevant skin lesions. No randomized clinical trial has been performed to demonstrate that using the AC rule or the more common ABCDE rule during mobile teledermoscopy improves the ability of laypersons to self-detect melanoma accurately.27

Other barriers reported by participants in this study included: difficulty taking photographs in hard-to-see locations and experiencing anxiety during the period of waiting for a telediagnosis. Mobile teledermoscopy may not be practical for whole body skin examinations for persons without access to help. The benefits of having well-trained partners assist in conducting skin checks in hard-to-see locations have been previously reported.28, 29 The anxiety levels of participants may have increased owing to a longer delay in receiving results than we found in previous studies. The waiting time in this study was due to having only one dermatologist to review the photographs. Previous research found that participants would prefer to receive their results ‘up to 1 day’ after conducting mobile teledermoscopy.30 In order to reduce any anxiety when conducting mobile teledermoscopy, the provision of results would need to be streamlined to provide a prompt service.

The present study included an older age demographic, and difficulty in downloading and personalizing the app was a barrier among a minority of participants. Younger patients may have fewer technological issues and may be more inclined to trust a mobile diagnosis given the greater likelihood that they conduct other aspects of their life online. In this research, most participants indicated that they would use mobile teledermoscopy if it saved them money. Many people own a smartphone and therefore they already have part of the equipment needed to conduct mobile teledermoscopy.31 Cost and technical support were found to contribute to user acceptance of telemedicine in a qualitative European study about user-end adoption of home telemedicine among adults 55–75 years of age.32 The cost of the most recent mobile dermatoscopes for smartphones ranges widely from about US$50 to US$600, but less costly innovative solutions may emerge in the future.

We are cautious about generalizing our findings to other settings, as we studied a relatively homogeneous sample of patients at high risk for melanoma. However, the implementation of this technology would likely focus on high-risk groups once it is rolled out and therefore restricting our study to high-risk patients was not unreasonable. Arguably, rural populations have the most to gain from telemedicine services and, although this research was completed in an urban population, the participants nonetheless reported high acceptance. Presumably, this was because they valued the time-saving benefit and appreciated the potential for rapid diagnosis. The items in the compatibility domain had a low Cronbach's alpha. These items may not fully discriminate compatibility because it is difficult to know how compatible a new technology is, especially if individuals have not used mobile teledermoscopy before. Therefore their scores might be inconsistent and contribute to a low Cronbach's alpha. These domains need further development and require items to be added in future questionnaires.

Despite high levels of acceptance and enthusiasm in this sample at high risk of melanoma, many practical aspects still need to be resolved before mobile teledermoscopy is ready for widespread consumer use. Further diagnostic studies to optimize acceptability and confidence of use are required to build consumer trust in the telediagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Melissa Manahan and Alison Marshall for their valuable contributions to this research and Catherine Olsen and the QSkin Sun and Health Study Team for their help with study recruitment.