The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial

Abstract

Objectives

Cariprazine, an orally active and potent dopamine D3 and D2 receptor partial agonist with preferential binding to D3 receptors, is being developed for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar mania. This Phase II trial evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of cariprazine versus placebo in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Methods

This was a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose study of cariprazine 3–12 mg/day in patients with acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. Following washout, patients received three weeks of double-blind treatment. The primary and secondary efficacy parameters were change from baseline to Week 3 in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and Clinical Global Impressions–Severity (CGI-S) scores, respectively. Post-hoc analysis evaluated changes on YMRS single items.

Results

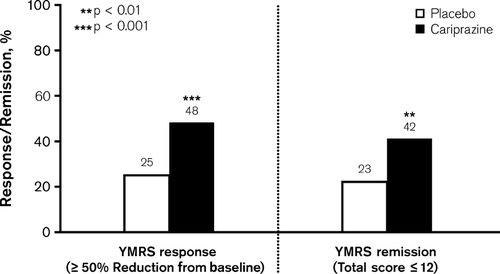

In each group, 118 patients received double-blind treatment; 61.9% of placebo and 63.6% of cariprazine patients completed the study. The overall mean daily dose of cariprazine was 8.8 mg/day. At Week 3, cariprazine significantly reduced YMRS and CGI-S scores versus placebo, with least square mean differences of −6.1 (p < 0.001) and −0.6 (p < 0.001), respectively. On each YMRS item, change from baseline to Week 3 was significantly greater for cariprazine versus placebo (all, p < 0.05). A significantly greater percentage of cariprazine patients than placebo patients met YMRS response (48% versus 25%; p < 0.001) and remission (42% versus 23%; p = 0.002) criteria at Week 3. Adverse events (AEs) led to discontinuation of 12 (10%) placebo and 17 (14%) cariprazine patients. The most common AEs (> 10% for cariprazine) were extrapyramidal disorder, headache, akathisia, constipation, nausea, and dyspepsia. Changes in metabolic parameters were similar between groups, with the exception of fasting glucose; increases in glucose were significantly greater for cariprazine versus placebo (p < 0.05). Based on Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale and Simpson–Angus Scale scores, more cariprazine than placebo patients experienced treatment-emergent akathisia (cariprazine: 22%; placebo: 6%) or extrapyramidal symptoms (parkinsonism) (cariprazine: 16%; placebo: 1%).

Conclusion

Cariprazine demonstrated superior efficacy versus placebo and was generally well tolerated in patients experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Bipolar I disorder is associated with a broad range of symptoms that can be challenging to treat. Effective therapies (e.g., second-generation antipsychotic agents and mood stabilizers) are currently available for acute manic or mixed episodes, but treatment often does not result in full symptomatic remission. The presence of unresolved symptoms has been shown to substantially contribute to functional impairment and reduced quality of life 1, 2, as well as increased risk of recurrence 3. Additionally, antipsychotic treatments currently available are associated with tolerability issues [e.g., weight gain, metabolic issues, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), sedation, and hyperprolactinemia] that can lead to reduced treatment adherence or discontinuation of therapy. New treatments with strong efficacy across a broad range of symptoms, coupled with good tolerability, are needed to improve patient outcomes in bipolar I disorder.

Cariprazine is an orally active and potent dopamine D3 and D2 receptor partial agonist with preferential binding to D3 receptors. Relative to other atypical antipsychotic agents, cariprazine binds with significantly higher in vitro affinity to dopamine D3 versus D2 receptors 4. Cariprazine also showed high and balanced occupancy in the rat brain in vivo at antipsychotic-like effective doses; by contrast, other antipsychotic agents demonstrated high occupancy at D2 receptors but low or no occupancy at D3 receptors 5. Although antipsychotic efficacy is thought to be mediated by D2 receptor blockade 6, it has been hypothesized that a compound exhibiting high affinity at D3 receptors in addition to D2 receptors may confer treatment advantages on mood symptoms and cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia and bipolar mania 7-10. In animal models, cariprazine showed potent antimanic-like 11 and antipsychotic-like 12 efficacy; cariprazine also demonstrated D3 receptor-mediated procognitive and antidepressant-like effects 13, 14, suggesting that it may be an effective treatment across a broad range of symptom domains in patients with bipolar I disorder. This Phase II trial (NCT00488618) evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of cariprazine versus placebo in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Methods

Patients from 29 study centers in the United States, Russia, and India participated in the study, which was conducted from June 2007 to July 2008. The final study protocol was approved by the ethics committees and appropriate authorities for all centers involved. The study was performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines; all patients provided informed, written consent.

Study design

A multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, flexible-dose study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cariprazine 3–12 mg/day in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. The study consisted of a drug washout period of up to four days, a three-week double-blind treatment period, and a two-week safety follow-up for patients who completed or prematurely discontinued. Patients were randomized on a 1:1 basis to either flexibly dosed cariprazine 3–12 mg/day or placebo. Cariprazine was initiated at 1.5 mg/day, dosage increased to 3 mg/day on Day 2, and thereafter dosage was increased in increments of 3 mg to a maximum of 12 mg/day by Day 5 based on response and tolerability. In the event of tolerability issues, dosage could be decreased in 3 mg decrements to a minimum of 3 mg/day.

Patients were hospitalized during the no-drug screening period (up to four days before randomization); those meeting eligibility criteria were randomized and remained hospitalized for a minimum of 14 days following double-blind treatment initiation. Starting on Day 14, patients could be discharged if all of the following criteria were met: Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) 15 score ≤ 3, no significant risk for suicide or violent behavior, and ready for discharge in the opinion of the investigator. If clinical deterioration occurred after discharge, patients could be readmitted to the hospital or placed in a day-treatment program.

Following three weeks of double-blind treatment or after premature discontinuation during the double-blind treatment phase, patients were evaluated for safety assessments for an additional two weeks; during this period they received treatment as usual at the discretion of the investigator.

Patients

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Men and women who were 18–65 years of age with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed type, with or without psychotic symptoms according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) 16 criteria and confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR participated in the study. A Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) 17 total score ≥ 20 and a score ≥ 4 on at least two of four items (Irritability, Speech, Content, and Disruptive/Aggressive Behavior) were also required. Some comorbid diagnoses (e.g., conduct disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders) were allowed. Women had to be at least two years postmenopausal, surgically sterile, or practicing a medically acceptable method of contraception; additionally, women could not be pregnant or nursing.

Exclusion criteria included other DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses (e.g., dementia, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other psychotic disorders), meeting the criteria for rapid cycling specifier, an Axis II diagnosis severe enough to interfere with participation, alcohol or substance abuse/dependence, a Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) 18 total score ≥ 18 at screening, first manic episode, manic symptoms resulting from prior antidepressant initiation, and electroconvulsive therapy or a depot neuroleptic within three months of screening. Patients with various medical conditions (e.g., malignancy within the past year, hematologic, endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal, neurologic disorders), a history of tardive dyskinesia or neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and significant abnormalities in physical examination, electrocardiography (ECG) results, or clinical laboratory values were also excluded. Imminent risk of injury, self-injury, suicide, MADRS Item 10 (Suicidal Thoughts) score ≥ 5 at screening and/or or a serious suicide attempt within the past year precluded participation. Treatment with an investigational agent within 90 days (or five half-lives) of screening or participation in a previous study of cariprazine was not allowed.

Concomitant medications

The use of psychotropic drugs (e.g., antipsychotic/neuroleptic agents, antidepressants, stimulants, mood stabilizers, sedatives/hypnotics/anxiolytics, dopamine-releasing drugs, or dopamine agonists) was not allowed; zolpidem, zolpidem extended release, zaleplon, chloral hydrate, or eszopiclone for insomnia were permitted. If EPS emerged or worsened during the study, the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) 19, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS) 20, and Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS) 21 were used to support a decision to administer rescue medication (e.g., diphenhydramine, benztropine, or propranolol for the treatment of akathisia). Lorazepam was permitted to control agitation, restlessness, irritability, and hostility. Allowable dosages of lorazepam decreased as the study progressed, with maximum dosages of 8 mg/day at Day 2 or before, 6 mg/day on Days 3–5, 4 mg/day on Days 6–8, and 2 mg/day on Days 9–11. Additionally, if patients required rescue medication, assessments were deferred until eight hours after the dose was received.

Outcome assessments

The scales used to assess primary and secondary efficacy were the YMRS and CGI-S, respectively. Both YMRS and CGI-S were administered at screening, baseline, and Days 2, 4, 7, 11, 14, and 21.

Additionally, the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI-I) scale 15 (Days 2, 4, 7, 11, 14, 21), MADRS (screening, baseline, Days 7, 14, 21), and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) 22 (baseline, Days 14, 21) were administered. Safety and tolerability were evaluated by adverse events (AEs) reports, laboratory tests (including hematology, fasting serum chemistry, urinalysis, and prolactin levels), 12-lead ECG, and vital signs. EPS were assessed by the AIMS, BARS, and SAS (baseline, Days 2, 4, 7, 11, 14, and 21).

Statistical methods

The safety population consisted of all randomized patients who took at least one dose of double-blind medication. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population comprised all patients in the safety population who also had at least one post-baseline YMRS total score assessment. Efficacy analyses were performed on the ITT population; safety analyses were performed on the safety population.

The percentage of patients who prematurely discontinued double-blind treatment (overall and by reason) was compared using Fisher's exact test. The between-group comparison of demographic and baseline characteristics was conducted using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model for continuous variables and Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test for categorical variables and adjusting for study center.

The primary efficacy parameter, change from baseline to Week 3 on the YMRS total score, was analyzed using an analysis of covariance model (ANCOVA), with treatment group and study center as factors and baseline score as a covariate. A last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) approach was used for imputation of missing data. Sensitivity analyses were performed using the observed case (OC) approach analyzed with an ANCOVA model and also using a mixed-effects model with repeated measures (MMRM) approach with treatment group, study center, assessment day, and treatment-group-by-assessment-day interaction as fixed effects and baseline YMRS total score as a covariate. The secondary efficacy parameter, change from baseline to Week 3 in CGI-S score, was analyzed using similar methodology as for the primary efficacy parameter.

Additional efficacy parameters included change from baseline to Week 3 in MADRS and PANSS total scores, CGI-I score at Week 3, and response (≥ 50% improvement from baseline in YMRS score) and remission (YMRS score ≤ 12) rates at Week 3. Change in MADRS and PANSS scores were analyzed using an ANCOVA method similar to the primary efficacy parameter. Analysis of CGI-I score at Week 3 was performed using an ANOVA model with treatment group and study center as factors. By-assessment-day analyses for all efficacy parameters were performed using the LOCF, OC, and MMRM approaches. The YMRS response and remission rates at Week 3 were analyzed by logistic regression, with baseline YMRS score and treatment group as explanatory variables; estimates for number needed-to-treat (NNT) were calculated for response and remission outcomes. Post-hoc analysis was conducted to evaluate change from baseline to Week 3 on YMRS single items using an ANCOVA model.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze AEs, clinical laboratory values, vital signs, ECG parameters [e.g., heart rate, QT interval, QTc Bazett (QTcB), QTc Fridericia (QTcF)], and potentially clinically significant (PCS) changes. Treatment-emergent EPS (parkinsonism) were defined as the SAS score ≤ 3 at baseline and > 3 at any post-baseline assessment; treatment-emergent akathisia was defined as the BARS score ≤ 2 at baseline and > 2 at any post-baseline assessment. Post-hoc statistical testing was performed for treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) and mean changes in fasting glucose from baseline to the end of double-blind treatment. The percentage of patients increasing from baseline fasting glucose levels < 126 mg/dL to post-baseline levels ≥ 126 mg/dL were also evaluated post hoc.

All statistical tests were two-sided, performed at the 5% level of significance; all confidence intervals (CIs) were two-sided 95% intervals, unless stated otherwise. For all efficacy measures, statistical significance was defined as p values < 0.05. To control for multiple comparisons for the primary and secondary efficacy parameters, a closed testing procedure was performed; the secondary efficacy parameter was only tested if the primary efficacy parameter was positive at the 0.05 level. Additional, post-hoc, and by-assessment-day efficacy outcomes were not controlled for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patient disposition and demographics

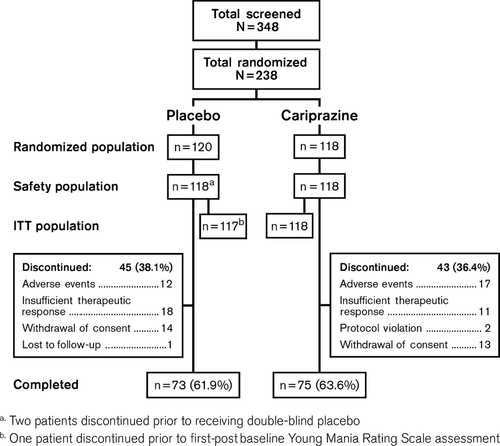

A total of 348 patients were screened and 238 patients were randomized to receive double-blind treatment; there were 236 patients in the safety population and 235 patients in the ITT population. Approximately 60% of patients were enrolled in the United States, 30% in India, and 10% in Russia. Completion rates were similar between treatment groups (placebo: 62%; cariprazine: 64%) and no statistically significant differences were observed between cariprazine- and placebo-treated patients for overall discontinuation rate or individual reason for discontinuation (Fig. 1).

There were no significant differences between treatment groups in baseline demographics; baseline disease characteristics were also similar between groups (Table 1). Mean YMRS total scores at baseline were 30.2 (placebo) and 30.6 (cariprazine), indicating a moderately to severely ill patient population 17. The mean treatment duration was approximately 17 days; the mean daily dosage for the cariprazine group was 8.8 mg/day. The final cariprazine dosage for most patients (66.1%) was 12 mg/day; 4.2%, 12.7%, and 16.9% of cariprazine-treated patients received a final dosage of 3, 6, and 9 mg/day, respectively.

| Placebo (n = 118) | Cariprazine (n = 118) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 38.7 (11.0) | 38.0 (10.3) |

| Men, n (%) | 77 (65.3) | 80 (67.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 55 (46.6) | 47 (39.8) |

| Black | 31 (26.3) | 36 (30.5) |

| Asian | 28 (23.7) | 30 (25.4) |

| Other | 4 (3.4) | 5 (4.2) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 79.3 (20.0) | 75.0 (20.3) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.2 (5.8) | 25.8 (5.9) |

| Disease characteristics | ||

| Duration of bipolar I disorder, years, mean (SD) | 14.8 (9.7) | 14.6 (9.1) |

| Age at onset, years, mean (SD) | 23.9 (10.2) | 23.4 (8.1) |

| Current episode, n (%) | ||

| Manic | 95 (80.5) | 96 (81.4) |

| Mixed | 23 (19.5) | 22 (18.6) |

| Duration of current manic episode, n (%) | ||

| ≤ 1 month | 78 (66.1) | 71 (60.2) |

| > 1 to 6 months | 36 (30.5) | 45 (38.1) |

| >6 months | 4 (3.4) | 2 (1.7) |

- BMI = body mass index; SD = standard deviation.

Efficacy

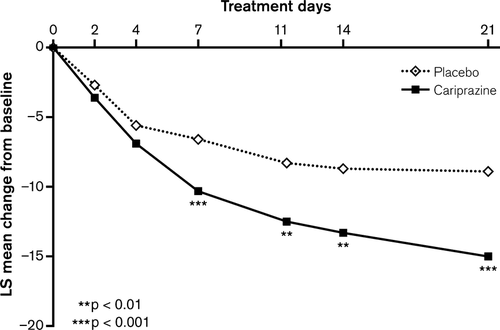

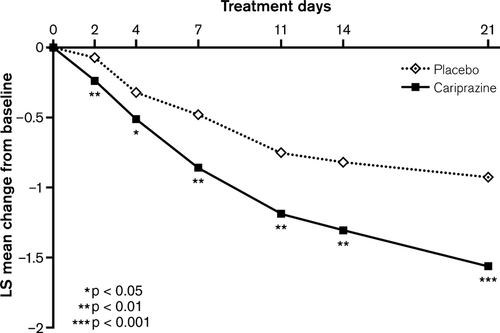

The change from baseline to end of Week 3 in YMRS total score was statistically significantly greater for cariprazine-treated patients compared with placebo-treated patients (LOCF) (Table 2, Fig. 2); a statistically significant advantage for cariprazine was observed on Day 7 and was maintained through the end of the trial (LOCF). MMRM and OC ANCOVA analyses supported the robustness of the primary result (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). Statistically significantly greater improvement on the CGI-S in favor of cariprazine was demonstrated as early as Day 2 and persisted through Week 3 (LOCF) (Fig. 3); similar results were also observed using OC ANCOVA and MMRM analyses (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 2).

| Placebo | Cariprazine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy measure | n | Value (SEM) | n | Value (SEM) | LSMD (95% CI) | p-value |

| YMRS total score (primary parameter) | ||||||

| Baseline, mean | 117 | 30.2 (0.5) | 118 | 30.6 (0.5) | – | 0.541 |

| LS mean change from baseline to Week 3 | ||||||

| LOCF | 117 | −8.9 (1.1) | 118 | −15.0 (1.1) | −6.1 (−8.9 to −3.3) | < 0.0001 |

| OC | 77 | −13.6 (1.0) | 81 | −19.1 (0.9) | −5.5 (−7.9 to −3.1) | < 0.0001 |

| MMRM | 117 | −8.5 (1.1) | 118 | −15.5 (1.1) | −7.0 (−10.0 to −4.0) | < 0.0001 |

| CGI-S (secondary parameter) | ||||||

| Baseline, mean | 117 | 4.6 (0.1) | 118 | 4.7 (0.1) | – | 0.514 |

| LS mean change from baseline to Week 3 | ||||||

| LOCF | 117 | −0.9 (0.1) | 118 | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.6 (−1.0 to −0.3) | 0.0001 |

| OC | 76 | −1.5 (0.1) | 81 | −2.0 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.8 to −0.2) | 0.0016 |

| MMRM | 117 | −0.9 (0.1) | 118 | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.4) | 0.0001 |

| Additional parameters | ||||||

| CGI-I | ||||||

| LS mean score at Week 3 | ||||||

| LOCF | 117 | 3.2 (0.1) | 118 | 2.4 (0.1) | −0.8 (−1.2 to −0.5) | < 0.0001 |

| OC | 76 | 2.5 (0.1) | 81 | 1.9 (0.1) | −0.7 (−1.0 to −0.3) | < 0.0001 |

| MMRM | 117 | 3.0 (0.1) | 118 | 2.2 (0.1) | −0.8 (−1.1 to −0.4) | < 0.0001 |

| PANSS total score | ||||||

| Baseline, mean | 117 | 60.5 (1.5) | 118 | 60.2 (1.3) | – | 0.428 |

| LS mean change from baseline to Week 3 | ||||||

| LOCF | 113 | −6.3 (1.2) | 113 | −9.9 (1.2) | −3.6 (−6.7 to −0.4) | 0.0269 |

| OC | 77 | −10.2 (1.3) | 81 | −14.2 (1.2) | −4.1 (−7.3 to −0.9) | 0.0131 |

| MMRM | 117 | −9.0 (1.3) | 118 | −12.2 (1.2) | −3.2 (−6.5 to 0.1) | 0.0556 |

| MADRS total score | ||||||

| Baseline, mean | 117 | 8.8 (0.4) | 118 | 9.0 (0.4) | – | 0.857 |

| LS mean change from baseline to Week 3 | ||||||

| LOCF | 115 | −2.0 (0.6) | 115 | −2.6 (0.6) | −0.6 (−2.1 to 0.9) | 0.4052 |

| OC | 77 | −3.3 (0.8) | 81 | −3.6 (0.7) | −0.3 (−2.3 to 1.8) | 0.7912 |

| MMRM | 117 | −2.5 (0.7) | 118 | −2.8 (0.7) | −0.3 (−2.1 to 1.6) | 0.7716 |

- CGI-I = Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement; CGI-S = Clinical Global Impressions–Severity; CI = confidence interval; ITT = intent-to-treat; LOCF = last observation carried forward; LS = least squares; LSMD = least squares mean difference; MADRS = Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MMRM = mixed-effects model with repeated measures; OC = observed cases; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SEM = standard error of the mean; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale.

Statistically significantly greater improvement was also demonstrated for cariprazine compared with placebo on all additional efficacy parameters except MADRS total score (LOCF; Table 2); mean MADRS total scores at baseline were very low, indicating no discernible depression, which did not worsen during the study.

At Week 3, a significantly greater percentage of cariprazine- compared with placebo-treated patients met the criteria for YMRS response (LOCF: 48% versus 25%; p < 0.001) and remission (LOCF: 42% versus 23%; p = 0.002) (Fig. 4); NNT estimates were 5 (95% CI: 3–9) and 6 (95% CI: 4–15) for response and remission, respectively.

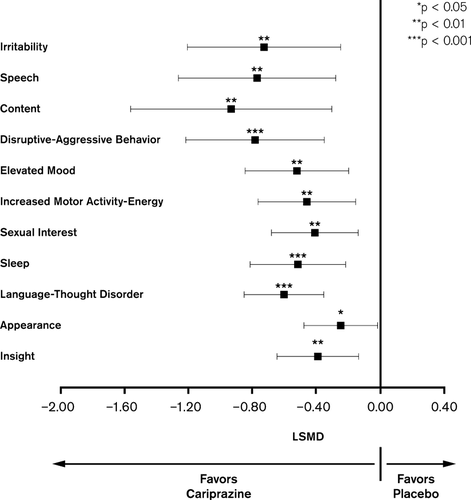

Post-hoc analyses of YMRS single items showed statistically significantly greater mean change from baseline to Week 3 on all items for the cariprazine group relative to placebo (Fig. 5).

Safety and tolerability

Adverse events

TEAEs were reported in 78.8% and 85.6% of placebo- and cariprazine-treated patients, respectively (Table 3); the majority of TEAEs in both groups were mild in severity (placebo: 68.0%; cariprazine: 70.8%) and considered to be related or possibly related to study drug (placebo: 67.4%; cariprazine: 73.1%). Common TEAEs (≥ 10% of cariprazine-treated patients) were extrapyramidal disorder, headache, akathisia, constipation, nausea, and dyspepsia. Only extrapyramidal disorder and akathisia occurred at a significantly higher incidence in cariprazine- relative to placebo-treated patients (both, p < 0.01); there were no other significant between-group differences in TEAEs. The majority (95%) of EPS-related TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity.

| Placebo (n = 118) n (%) | Cariprazine (n = 118) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SAEsa | 5 (4.2) | 4 (3.4) |

| AEs leading to discontinuationb | 12 (10.2) | 17 (14.4) |

| Any TEAE | 93 (78.8) | 101 (85.6) |

| TEAEs (≥ 5%) | ||

| Extrapyramidal disorder | 11 (9.3) | 29 (24.6)c |

| Headache | 24 (20.3) | 23 (19.5) |

| Akathisia | 7 (5.9) | 22 (18.6)c |

| Constipation | 10 (8.5) | 18 (15.3) |

| Nausea | 12 (10.2) | 18 (15.3) |

| Dyspepsia | 8 (6.8) | 15 (12.7) |

| Dizziness | 8 (6.8) | 11 (9.3) |

| Insomnia | 3 (2.5) | 10 (8.5) |

| Vomiting | 4 (3.4) | 10 (8.5) |

| Diarrhea | 8 (6.8) | 7 (5.9) |

| Restlessness | 1 (0.8) | 7 (5.9) |

| Sedation | 1 (0.8) | 7 (5.9) |

| Vision blurred | 1 (0.8) | 7 (5.9) |

| Mania | 8 (6.8) | 6 (5.1) |

| Pain in extremity | 3 (2.5) | 6 (5.1) |

| Pyrexia | 5 (4.2) | 6 (5.1) |

| Tremor | 5 (4.2) | 6 (5.1) |

| Agitation | 8 (6.8) | 5 (4.2) |

| Toothache | 7 (5.9) | 3 (2.5) |

- AE = adverse event; SAE = serious adverse event; TEAE = treatment-emergent adverse event.

- a SAEs were reported in five additional patients before the start of double-blind treatment.

- b One patient discontinued prior to receiving study drug.

- c p < 0.01 versus placebo.

During the study, there were no reports of suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, or overdoses for cariprazine-treated patients. However, one placebo-treated patient reported suicidal ideation on Day 15; the patient completed the study. No significant cardiac TEAEs (e.g., abnormal ECG, congestive heart failure, ventricular flutter) were reported.

Serious adverse events

A total of ten serious AEs (SAEs) in nine patients (six in five placebo-treated and four in four cariprazine-treated patients) were reported during the double-blind treatment phase. The most common SAE was worsening of mania, which occurred in six patients (four placebo; two cariprazine). In addition, delusion/delusional thinking (n = 1) and hypertension (n = 1) were reported in the placebo group; convulsions (n = 1) and extrapyramidal disorder/severe EPS (n = 1) were reported in the cariprazine group. During safety follow-up, 14 patients reported SAEs; the most common were worsening of mania (four placebo; five cariprazine) and bipolar disorder (zero placebo; two cariprazine). The percentage of patients receiving lorazepam to control agitation was similar between the cariprazine (79%) and placebo (77%) groups; mean daily lorazepam doses were also similar between the cariprazine (0.44 mg/day) and placebo (0.42 mg/day) groups.

AEs leading to discontinuation

During double-blind treatment, 12 (10.2%) placebo-treated and 17 (14.4%) cariprazine-treated patients discontinued the trial owing to AEs. The most frequent AE leading to discontinuation was worsening of mania (six placebo; three cariprazine). Other AEs that led to the discontinuation by two or more patients in either treatment group were akathisia, restlessness, and agitation. For eight of the 29 patients (five placebo; three cariprazine) who discontinued owing to AEs during double-blind treatment, the AEs were also categorized as SAEs.

Clinical laboratory values and vital signs

Mean changes from baseline in metabolic parameters (glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides) were generally small and similar between groups (Table 4), with the exception of fasting glucose; increase in fasting glucose was significantly greater with cariprazine relative to placebo (p = 0.04). The proportion of patients with PCS changes in metabolic parameters was similar between groups. The percentage of patients shifting to glucose levels ≥ 126 mg/dL at endpoint was low and similar between groups, regardless of baseline glucose levels (< 100, 100 to < 126, or < 126 mg/dL) (Table 4). Prolactin levels decreased in both treatment groups (cariprazine: −3.0 ng/mL; placebo: −3.3 ng/mL). A higher percentage of cariprazine-treated (4.3%) than placebo-treated (0.9%) patients had a PCS elevation in alanine aminotransferase values (≥ 3 × upper limit of normal); the majority of the cases were transient and none met the criteria for Hy's law 23.

| Parameters | Placebo (n = 118) | Cariprazine (n = 118) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Vital signs | ||||

| Supine SBP, mmHg | ||||

| Baseline | 118 | 124.6 (12.5) | 118 | 121.8 (11.9) |

| Change | 117 | −0.1 (13.1) | 118 | 2.6 (12.1) |

| Supine DBP, mmHg | ||||

| Baseline | 118 | 78.1 (8.3) | 118 | 78.0 (8.4) |

| Change | 117 | 1.5 (8.5) | 118 | 1.6 (9.0) |

| Supine pulse rate, bpm | ||||

| Baseline | 118 | 78.4 (11.2) | 118 | 78.4 (10.3) |

| Change | 117 | −1.0 (12.0) | 118 | 2.7 (11.7) |

| Body weight, kg | ||||

| Baseline | 118 | 79.3 (20.0) | 118 | 75.0 (20.3) |

| Change | 117 | −0.1 (2.1) | 118 | 0.6 (2.0) |

| Metabolic parameters | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 114 | 179.6 (42.7) | 116 | 177.7 (41.7) |

| Change | 114 | 2.8 (30.3) | 116 | 0.0 (28.2) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 114 | 105.7 (37.5) | 116 | 103.7 (35.1) |

| Change | 114 | 3.2 (29.1) | 116 | −0.3 (25.3) |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 114 | 46.8 (12.1) | 116 | 50.1 (14.7) |

| Change | 114 | −1.0 (10.2) | 116 | −0.8 (11.0) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 114 | 135.1 (78.1) | 116 | 119.3 (63.6) |

| Change | 114 | 2.5 (72.8) | 116 | 5.9 (65.0) |

| Glucose, fasting, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 104 | 93.6 (18.3) | 110 | 88.9 (15.7) |

| Change | 104 | −0.2 (19.9) | 110 | 7.7 (21.0)a |

| Incidence of increases in fasting glucose, n (%) | ||||

| < 100 mg/dL at baseline to ≥ 126 mg/dL at endpoint | 1/104 (1.0) | 1/110 (0.9) | ||

| ≥ 100 and < 126 mg/dL at baseline to ≥ 126 mg/dL at endpoint | 3/104 (2.9) | 1/110 (0.9) | ||

| < 126 mg/dL at baseline to ≥ 126 mg/dL at endpoint | 4/104 (3.8) | 2/110 (1.8) | ||

- DBP = diastolic blood pressure; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SD = standard deviation.

- a p < 0.05 versus placebo.

Mean changes in blood pressure and pulse were slightly higher in the cariprazine groups relative to placebo (Table 4). The incidence of PCS changes in vital sign parameters during the double-blind phase was low and similar between treatment groups; the incidence of orthostatic hypotension was also similar between groups (placebo: 23%; cariprazine: 18%). Mean change in body weight was small and similar between groups; PCS increases in weight (≥ 7%) were low and similar between groups (placebo: zero patients; cariprazine: three patients). Mean change in QTcB and QTcF interval was small and similar between groups (QTcB: placebo: 2.0 msec; cariprazine: 3.8 msec; QTcF: placebo: 0.9 msec; cariprazine: −1.3 msec). No PCS post-baseline ECG values (i.e., QRS interval ≥ 150 msec, PR interval ≥ 250 msec, QTcB interval > 500 msec, QTcF interval > 500 msec) were reported.

EPS

Mean change from baseline to Week 3 in AIMS total score (placebo: 0.04; cariprazine: 0.01; p = 0.927) and BARS total score (placebo: 0.09; cariprazine: 0.40; p = 0.122) were small and similar between groups. Mean change in SAS total score was higher for cariprazine relative to placebo (placebo: 0.09; cariprazine: 1.17; p < 0.01). A total of one (0.9%) placebo-treated patient and 19 (16.1%) cariprazine-treated patients experienced treatment-emergent EPS (parkinsonism) (SAS score ≤ 3 at baseline and > 3 at any post-baseline assessment) during double-blind treatment; the rates of treatment-emergent akathisia (BARS score ≤ 2 at baseline and > 2 at any post-baseline assessment) during double-blind treatment were seven (6.0%) for placebo and 26 (22.0%) for cariprazine.

All patients who met the criteria for treatment-emergent EPS (parkinsonism) and most patients who met the criteria for treatment-emergent akathisia also had at least one movement disorder-related TEAE. The most frequently occurring movement disorder-related TEAEs were extrapyramidal disorder (placebo: 9.3%; cariprazine: 24.6%) and akathisia (placebo: 5.9%; cariprazine: 18.6%). Most movement disorder-related TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity and rarely resulted in premature discontinuation [cariprazine: two (1.7%) for akathisia and one (0.8%) for extrapyramidal disorder; none for placebo]. The incidence of dystonia was infrequent, occurring in only one placebo patient (0.8%) and two cariprazine patients (1.7%). Symptoms were easily managed by rescue medication. A higher percentage of patients in the cariprazine treatment group relative to the placebo group used anti-parkinsonian drugs (cariprazine: 37.3%; placebo: 22.0%) and propranolol (cariprazine: 7.6%; placebo: 1.7%) to control EPS.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the efficacy of cariprazine in treating adult patients with acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder. On the primary efficacy parameter, YMRS total score change from baseline to Week 3, statistical superiority over placebo was demonstrated beginning at Day 7. Sensitivity analyses using OC and MMRM approaches supported the primary result. A significantly greater change in CGI-S scores relative to placebo showed that treatment with cariprazine decreased the overall severity of disease.

Cariprazine also demonstrated efficacy on the additional efficacy outcomes, with a significant improvement in favor of cariprazine demonstrated on all measures except the MADRS. Patients with MADRS scores ≥ 18 were excluded, so mixed episodes comprised only mild depression. Mean MADRS baseline scores were low at baseline and decreased throughout the study, suggesting that depressive symptoms were not precipitated by cariprazine treatment.

Almost twice as many cariprazine- compared with placebo-treated patients achieved response (cariprazine: 48%; placebo: 25%) and remission (cariprazine: 42%; placebo: 23%) during this short-term study. In bipolar disorder, response and remission rates corresponding to an NNT value of < 10 signify a clinically relevant effect 24. In the present study, the NNT values for cariprazine were 5 and 6 for response and remission, respectively.

In a post-hoc analysis, cariprazine showed a significant improvement versus placebo on all 11 YMRS single items. This suggests that cariprazine may offer efficacy across the broad range of mania symptoms. Unresolved symptoms following treatment are common and contribute to functional impairment, reduced quality of life 1, 2, and increased risk of recurrence/relapse relative to patients who achieve full symptomatic relief 3. Compounds with broad efficacy across the range of mania symptoms may better minimize unresolved symptoms and result in more favorable treatment outcomes.

Cariprazine was generally well tolerated, with similar rates of study completion observed between groups. Most TEAEs that occurred during the double-blind treatment phase were mild in severity.

Treatment with antipsychotic agents has been associated with weight gain, metabolic issues, sedation, EPS, hyperprolactinemia, QT prolongation, and orthostatic hypotension. In the present study, the incidence of clinically significant weight gain with cariprazine treatment was low. Mean changes in metabolic parameters were small and similar between groups, with the exception of fasting glucose; increases in fasting glucose were significantly greater in cariprazine patients compared with placebo patients. However, the percentage of patients shifting from normal (< 100 mg/dL) or prediabetic (100 to < 126 mg/dL) glucose levels at baseline to high post-baseline levels (≥ 126 mg/dL) was low and similar between groups. PCS changes in metabolic parameters were also similar between cariprazine and placebo. While the incidence of sedation was higher in cariprazine-treated patients (5.9%) than in placebo-treated patients (0%), the levels of sedation with cariprazine in the present study were relatively low 25. Cariprazine did not affect prolactin levels, with similar decreases from baseline observed in both treatment groups. No patient had a post-baseline QT interval prolongation exceeding 500 msec at any time during the study. The emergence of orthostatic hypotension following antipsychotic treatment can potentially delay or limit dose titration. In the present trial, the incidence of orthostatic hypotension was similar between groups.

Cariprazine-treated patients reported a significantly greater incidence of extrapyramidal disorder (25% versus 9%) and akathisia (19% versus 6%) compared with placebo-treated patients. These findings were consistent with data from the BARS and SAS assessments, which indicated a higher incidence of treatment-emergent akathisia (cariprazine: 22%; placebo: 6%) and treatment-emergent EPS (parkinsonism) (cariprazine: 16%; placebo: 1%) in the cariprazine group versus the placebo group. Most movement disorder-related TEAEs (95%) were considered mild or moderate in severity and the discontinuation rate due to movement disorder-related TEAEs was low (< 2%).

The efficacy of atypical antipsychotic agents as a class has been demonstrated in the treatment of mania, but the clear superiority of one agent over another has not been established 26, 27. An independent 2011 meta-analysis 27 compared the findings from randomized, placebo-controlled, short-term trials of 17 antipsychotic agents and mood stabilizers; the results from the present cariprazine study (NCT00488618) were included via data obtained from a conference presentation 28. For all eight of the second-generation antipsychotic agents tested (aripiprazole, asenapine, cariprazine, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone), a significant improvement over placebo was demonstrated; the agents as a group yielded an effect size of 0.40 (95% CI, 0.32–0.47; p < 0.0001). The atypical antipsychotic agents that appeared to be the most effective compared with placebo were risperidone (effect size = 0.66; three trials) and cariprazine (effect size = 0.51; one trial); at least moderate effect sizes were observed for the other atypical agents. Among first-generation antipsychotic agents and mood stabilizers, the highest effect sizes were observed with carbamazepine (effect size = 0.61; two trials) and haloperidol (effect size = 0.54; five trials). This meta-analysis suggested that the efficacy of cariprazine may be similar to that of established antimanic agents; however, conclusions were limited by the small size of the cariprazine data set, which was based on a single phase II cariprazine trial (n = 236).

Additionally, several recent meta-analyses have reported response and remission NNT estimates for various agents in the treatment of acute mania 24, 25, 27, 29. The NNT for response for cariprazine versus placebo in the current study (NNT = 5) was similar to that observed with seven other atypical antipsychotic agents tested in these meta-analyses (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, asenapine, and paliperidone); NNT values for response versus placebo for these compounds ranged from 4 (risperidone) to 13 (paliperidone) 24, 25, 27, 29. Remission rates for cariprazine (NNT = 6) were similar to those with other atypical antipsychotic agents, which showed NNT values for remission ranging from 4 (risperidone) to 10 (aripiprazole) 29. Taken together, these data suggest that cariprazine is effective in achieving response and remission in patients with bipolar I disorder, with treatment effects comparable with currently available antipsychotic agents.

Similar to other mania studies, the short duration of the trial and the lack of a comparator agent are considered to be limitations of the present study.

In the current Phase II clinical trial, cariprazine demonstrated superior efficacy relative to placebo and was generally well tolerated in patients with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. Efficacy in post-hoc YMRS single-item analyses further established the potential benefits of cariprazine for antimanic efficacy across a broad spectrum of symptoms. These positive results suggest that cariprazine is a promising treatment for bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from Forest Laboratories, Inc. (New York, NY, USA) and Gedeon Richter Plc (Budapest, Hungary). Forest Laboratories, Inc. and Gedeon Richter Plc were involved in the study design, collection (via contracted clinical investigator sites), analysis, and interpretation of data, and the decision to present these results. We would like to acknowledge Kelly Papadakis, previously of Forest Research Institute, for her contributions as the Study Physician/Clinical Director of the study. Writing assistance and editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Paul Ferguson of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL, USA), contractor for Forest Research Institute. The authors would also like to thank the following site investigators of this study: Barbara A. Burtner, Bradley C. Diner, Mary Ann Knesevich, Adam F. Lowy, Tram K. Tran-Johnson, David P. Walling, Morteza Marandi, Shrinivasa Bhat Undaru, Ramanathan Sathianathan, and Robert E. Litman.

Disclosures

SD, AS, DL, and RM are employees of Forest Research Institute (FRI) and own FRI stock. AR is an employee of Prescott Medical Communications Group, an FRI contractor. GN and IL are employees of Gedeon Richter Plc.