Successful rearing of common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) fed a formulated feed in an offshore cage

The unavailability of juveniles obtained in captivity and the lack of formulated feeds have been established as the main drawbacks for the development of cephalopod aquaculture (Iglesias & Fuentes, 2014; Sánchez, Cerezo Valverde, & García García, 2014). However, in the last decade, the format, the nutritional composition and the formulation of feeds have been improved (Cerezo Valverde, Hernández, Aguado-Giménez, & García García, 2017; Estefanell, Roo, Guirao, Afonso, et al., 2012; Martínez-Montaño et al., 2018; Morillo-Velarde, Cerezo Valverde, Hernández, Aguado-Gimenez, & García García, 2012; Querol et al., 2015; Rodríguez-González, Cerezo Valverde, Sykes, & García García, 2015) and, recently, studies that have offered good results at laboratory scale have been published (Cerezo Valverde & García García, 2017; Martínez et al., 2014). For large-scale production, the availability of a low-cost feed is essential. In an economic-financial analysis of the viability of octopus ongrowing in sea cages, García García and García García (2011) estimated that feeding with natural diets would represent the most important production cost (38%–40% of the total).

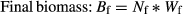

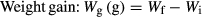

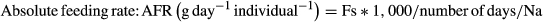

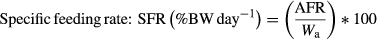

In the present study, a 76-day ongrowing cycle of sub-adult common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) was carried out in an offshore cage, using a formulated feed. The formulation and elaboration of the feed (GEL10-Fish), which was mainly based on freeze-dried raw materials and binders, were previously detailed in Cerezo Valverde and García García (2017). The proximal composition of the specific feed batch for this test (Table 1) was analysed (AOAC, 1997).

| Moisture | 463.1 ± 6.8 |

| Crude protein | 662.3 ± 3.4 |

| Crude lipid | 70.0 ± 4.5 |

| Ash | 59.3 ± 0.7 |

| CHOa | 208.3 ± 2.7 |

| Energy (kJ/100 g) | 2,183.3 ± 7.9 |

| P/Eb (g/MJ) | 30.3 ± 0.3 |

| WDRc (%) | 18.2 ± 1.9 |

- a CHO: Total carbohydrates, calculated by difference.

- b P/E: Protein/Energy ratio.

- c WDR: Water disintegration rates (WDR, % dry matter loss at 24 hr).

The octopuses were caught in the Mediterranean Sea (Murcia, S.E. Spain) by trawling and kept in 850 L tanks at the IMIDA facilities until the number of specimens needed for the trial was reached. Before starting the experiment, the animals were allowed to acclimatize for 10 days and fed with crab (Carcinus mediterranus), bogue (Boops boops) and the formulated feed on alternate days (García García & Cerezo Valverde, 2006; Rodríguez-González, Cerezo Valverde, Sykes, & García García, 2018). A total of 181 octopuses were used for the ongrowing cycle in offshore conditions (OFS group) and another 11 specimens were conditioned in a 2000 L tank at the IMIDA laboratory to carry out a parallel trial with the same feed (LAB group). The initial body weights (BWs) (March 30, 2017) were measured at the IMIDA facilities: 835 ± 167 g (OFS group) and 848 ± 147 g (LAB group). The OFS animals were transferred in 500 L plastic tanks containing well aerated seawater on board a boat belonging to the private company PESCAMUR S.L. to a cage located 4.8 km off the coast in the aquaculture area of San Pedro del Pinatar (SW Mediterranean: 37°49′N; 0°40′W). The traditional floating cage, 16 m in diameter and 10 m deep, contained 250 PVC pipes (15 cm diameter and 25 cm long) at the bottom as a shelter. The external net was made of nylon (2.5 cm longest mesh diagonal) and was fixed to the top of the railing to prevent escapes.

The animals were fed 4 days a week on alternate days (Mon, Wed, Thu and Sat) according to Rodríguez-González et al. (2018) from the surface by means of a boat rented by IMIDA or the PESCAMUR boat. A diver made a weekly count of the surviving specimens, and the temperature values were recorded daily. The significant wave height (SWH) was obtained from the oceanographic data of the Spanish state ports website (http://www.puertos.es/es-es/oceanografia/Paginas/portus.aspx).

Five animals taken from the sea were selected before the beginning of the trial (initial animals) and another five from each group (OFS or LAB) at the end of the ongrowing cycle to analyse the whole proximate composition (AOAC, 1997). The differences were analysed by one factor ANOVA and Tukey's test to establish homogenous groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 was established.

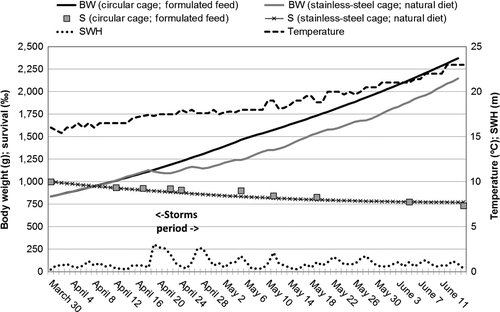

The water temperature gradually increased from 15 to 23°C during the ongrowing cycle (18.6 ± 2.0°C; Figure 1). Three strong storms were recorded, two in the first month and another in the second, which were reflected in the SWH (Figure 1). The temperature was controlled in the LAB group (17.9 ± 0.5°C).

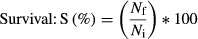

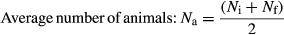

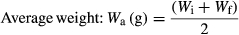

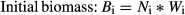

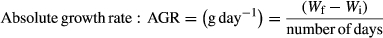

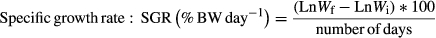

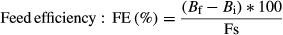

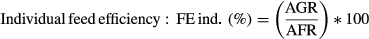

It was possible to verify the high acceptance of the feed by the octopuses from the first day. A total of 379 kg of formulated feed were distributed in absolute feeding rates of 5–12 kg/day in the OFS group (2.5%–5.1% biomass/day). The mean BW increased from 835 ± 167 g to 2,410 ± 441 g with an absolute growth rate of 20.7 g/day (1.4% BW/day; Table 1). The higher growth rate was recorded in the second ongrowing period (days 36–76; 23.0 g/day) with 10% animals exceeding 3 kg at the end of the trial. The SFR, FE ind. and FCR ind. were 2.0% BW/day, 65.2% and 1.5, respectively. The survival for the whole rearing cycle was 73.5%. The results were similar in the LAB group, although survival was higher (90.9%) and a growth lower (18.7 g/day). There were no significant differences in the DGI (p > 0.05).

Regarding the nutritional composition, there were no significant differences between the LAB group and initial animals before the trial (p > 0.05). However, the OFS animals had higher lipid content than the LAB group (p < 0.05), suggesting an influence of rearing conditions. Moreover, the OFS group showed higher protein content than initial levels (p < 0.05). Both the OFS and LAB groups was within the normal values for animals fed natural diet, that is, 739–821 g protein/kg, 13–24 g lipids/kg and 103–110 g ash/kg according to García García and Cerezo Valverde (2006).

Many studies have described the good results possible for ongrowing octopus provided with a natural diet in cages (Estefanell, Roo, Guirao, Izquierdo, & Socorro, 2012; García García, Cerezo Valverde, Aguado-Giménez, & García García, 2009; Rodríguez, Carrasco, Arronte, & Rodríguez, 2006). A simulation and comparison of growth and survival in a Mediterranean offshore cage can be carried out from the equations developed by García García et al. (2009) under the same conditions of weight and temperature (Figure 1). The main differences between the two studies are the diet (natural diets vs. formulated feed) and the type of cage (rectangular stainless steel with animals on the surface vs. circular with animals at 10 m depth). The growth was the same during the first 3 weeks, but two storms would have penalized the growth of the animals on the surface (2,200 g final weight vs. 2,400 g in OFS group; Figure 1). These results suggest that keeping octopuses at a certain depth could improve the yield. Moreover, there are benefits of a more stable temperature if the superficial layer of water is avoided. Estefanell, Roo, Guirao, Izquierdo, et al. (2012) also obtained excellent ongrowing results keeping the octopuses at the bottom in a benthic cage and discussed its possible benefits compared with the traditional floating cage.

Survival in the OFS group was lower (73.5%) compared with the values estimated by García García et al. (2009) (77.1%) in the same conditions of BW and coefficient of variation. We observed two factors that may have been responsible for increases in mortality in OFS group. Firstly, samplings created stress because of manipulation. In the mid-point sampling, the fact that non-sampled animals attacked the sampled animals when they were returned to the cage may be associated with territorial behaviour but also to the normal response of animals when they are feeding and see food falling from the surface. In this sense, it is better to restrict the samplings to the beginning and at the end of the ongrowing cycle. Secondly, the storms mentioned above sometimes prevented the animals from being fed for two consecutive days, which resulted in losses from hunger and cannibalism on the third day.

It is concluded that a natural diet based on fish and crustaceans could be replaced by a formulated feed without diminishing culture yield. Future studies could be directed towards finding low-cost alternative raw materials for this formulated feed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the “Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria” (INIA-Project RTA2012-00072-00-00). We thank Productos Sur S.A. for their advice on the binders used.

| Rearing conditions | IMIDA 2000-L tank | Offshore sea-cage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | 1–35 | 36–76 | 1–76 | 1–35 | 36–76 | 1–76 |

| T (°C) | 18.0 ± 0.6 | 17.7 ± 0.5 | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 16.9 ± 0.7 | 20.1 ± 1.5 | 18.6 ± 2.0 |

| N i | 11 | 11 | 11 | 181 | 163 | 181 |

| N f | 11 | 10 | 10 | 164 | 133 | 133 |

| S (%) | 100.0 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 90.6 | 81.6 | 73.5 |

| Wi (g) | 848 ± 147 | 1,485 ± 234 | 848 ± 147 | 835 ± 167 | 1,466 ± 292 | 835 ± 167 |

| Wi range (g) | 626–1,086 | 1,100–1822 | 626–1,086 | 446–1,280 | 850–2,350 | 446–1,280 |

| Wf (g) | 1,485 ± 234 | 2,273 ± 458 | 2,273 ± 458 | 1,466 ± 292 | 2,410 ± 441 | 2,410 ± 441 |

| Wf range (g) | 1,100–1822 | 1,286–2,857 | 1,286–2,857 | 850–2,350 | 1,370–3,790 | 1,370–3,790 |

| Wg (g) | 637 | 788 | 1,425 | 631 | 944 | 1575 |

| Bg (kg) | 7.0 | 6.4 | 13.4 | 89.3 | 81.6 | 169.4 |

| Fs (kg) | 10.0 | 14.9 | 24.9 | 153.8 | 225.2 | 379.1 |

| AFR (g day−1 ind.−1) | 26.80 | 34.10 | 30.83 | 25.48 | 37.11 | 31.77 |

| SFR (%BW/day) | 2.30 | 1.81 | 1.98 | 2.21 | 1.92 | 1.96 |

| AGR (g day−1 ind.−1) | 18.74 | 18.76 | 18.75 | 18.03 | 23.02 | 20.72 |

| SGR (%BW/day) | 1.65 | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.61 | 1.21 | 1.39 |

| FE (%) | 69.91 | 42.95 | 53.80 | 58.05 | 36.22 | 44.69 |

| FE ind. (%) | 69.93 | 55.02 | 60.81 | 70.76 | 62.03 | 65.23 |

| FCR | 1.43 | 2.33 | 1.86 | 1.72 | 2.76 | 2.24 |

| FCR ind. | 1.43 | 1.82 | 1.64 | 1.41 | 1.61 | 1.53 |

| DGI (%) | 3.83 ± 1.19 | 3.37 ± 0.95 | ||||

Note

- AGR: absolute growth rate; AFR: absolute feeding rate; Bg: biomass gain; DGI: digestive gland index; FCR: feed conversion ratio; FCR ind.: individual feed conversion ratio; FE: feed efficiency; FE ind.: individual feed efficiency; Fs: feed supplied; Nf: final number of animals; Ni: initial number of animals; S: Survival; SFR: specific feeding rate; SGR: specific growth rate; T: temperature; Wf: final weight; Wg: weight gain; Wi: initial weight.

| Rearing conditions | Initial (N = 5) | IMIDA 2000 L tank (N = 5) | Offshore cage (N = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 823.0 ± 18.2 | 832.3 ± 16.6 | 833.4 ± 25.0 |

| Crude protein | 771.4 ± 35.7a | 782.8 ± 3.2ab | 812.9 ± 19.8b |

| Crude lipid | 17.2 ± 6.6ab | 10.8 ± 6.7a | 23.0 ± 9.0b |

| Ash | 137.4 ± 13.7 | 128.3 ± 17.1 | 106.6 ± 25.9 |

| CHO | 71.8 ± 26.8 | 88.6 ± 7.7 | 75.8 ± 44.5 |

Note

- CHO. Total carbohydrates, calculated by difference.

- Different superscripts mean significant differences (p < 0.05)