Meta-analysis: Post-COVID-19 functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome

Giovanni Marasco and Marcello Maida equally contributed and shared co-first authorship.

As part of AP&T’s peer-review process, a technical check of this meta-analysis was performed by Dr Y Yuan.

The Handling Editor for this article was Professor Alexander Ford, and it was accepted for publication after full peer-review.

Summary

Introduction

The burden of post-COVID-19 functional dyspepsia (FD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) remains unclear. The aim of this meta-analysis was to estimate the rate of post-COVID-19 FD and IBS.

Methods

MEDLINE, Scopus and Embase were searched through 17 December 2022. Studies reporting the incidence of FD and/or IBS in COVID-19 survivors and controls (without COVID-19), when available, according to the Rome criteria, were included. Estimated incidence with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was pooled. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was pooled; heterogeneity was expressed as I2.

Results

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Overall, four studies including 1199 COVID-19 patients were considered for FD. Post-COVID-19 FD was reported by 72 patients (4%, 95% CI: 3%–5% and I2 0%). The pooled OR for FD development (three studies) in post-COVID-19 patients compared to controls was 8.07 (95% CI: 0.84–77.87, p = 0.071 and I2 = 67.9%). Overall, 10 studies including 2763 COVID-19 patients were considered for IBS. Post-COVID-19 IBS was reported by 195 patients (12%, 95% CI: 8%–16%, I2 95.6% and Egger's p = 0.002 test). The pooled OR for IBS development (four studies) in COVID-19 patients compared to controls was 6.27 (95% CI: 0.88–44.76, p = 0.067 and I2 = 81.4%); considering only studies with a prospective COVID-19 cohort (three studies), the pooled OR was 12.92 (95% CI: 3.58–46.60, p < 0.001 and I2 = 0%).

Conclusions

COVID-19 survivors were found to be at risk for IBS development compared to controls. No definitive data are available for FD.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread globally with over 647 million confirmed cumulative cases according to the World Health Organization on 17 December 2022.1 Beside the burden for healthcare systems and the significant morbidity and mortality led by COVID-19,2-4 there is increasing concern about the long-term consequences of COVID-19.5 This clinical condition, also known as ‘long COVID-19’ or ‘post-acute sequelae of COVID-19’, is characterised by the persistence of residual manifestation or the onset of new symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection, including pulmonary impairment, neurologic disorders, mental health disorders, functional mobility impairments and general and constitutional symptoms.6, 7 A recent cross-sectional study suggested the presence of at least one post-COVID-19 symptom in 59.7% of hospitalised patients and 67.5% of non-hospitalised patients 2 years after infection.8

Among post-COVID-19 manifestation, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, anorexia, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting have also been reported in a non-negligible rate of patients.2, 6, 9 Taken together, these gastrointestinal symptoms may shape a number of post-infection disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBI),10 conditions characterised by new-onset, Rome criteria-positive disorders after an episode of acute gastroenteritis in individuals who did not have DGBI before the infection.11 We recently reported12 that 1 year after hospitalisation, patients with COVID-19 had fewer problems of constipation and hard stools but reported higher rates of post-infection irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) compared with non-infected controls. In addition, COVID-19 patients reported higher rates of functional dyspepsia (FD), although without statistical significance.12 Previous studies reported heterogeneous results with this regard.13, 14

Therefore, the real burden of newly diagnosed FD and IBS affecting COVID-19 survivors still needs to be clarified. Thus, we aimed to assess the incidence of FD and IBS in COVID-19 survivors and its association with COVID-19 diagnosis compared to controls.

2 METHODS

A systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out in line with PRISMA (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines.15

2.1 Search strategy and selection criteria

Primary sources of the reviewed studies were MEDLINE via PubMed, Scopus and Ovid Embase, which were searched systematically up to 17 December 2022.

Searches included combinations of the following keywords: ‘dyspepsia’ or ‘irritable bowel syndrome’ or ‘gastrointestinal diseases’ or ‘functional gastrointestinal disorders’ and ‘coronavirus’ or ‘SARS-CoV-2’. The complete search strategies are reported in Appendix S1. The first report of cases of COVID-19 have been published on 15 February 2020 which16 have been elected as initial date for literature search. Besides, the abstracts of the conference proceedings of Digestive Diseases Week, the United European Gastroenterology Week and Asia Pacific Digestive Week from the same period were searched electronically and by hand. The references list of the studies and relevant published reviews included were searched. There were no restrictions on language or publication status. Two authors (GM and MM) carried out the initial selection based on titles and abstracts. A detailed full-text assessment of potentially relevant publications was independently carried out by the two reviewers, with any discrepancies being resolved through discussion or arbitration by a third reviewer (GB). Database searches were supplemented with literature searches of reference lists from potentially eligible articles to find additional studies.

2.1.1 Eligibility criteria

Studies were selected for inclusion if they met the following pre-specified criteria: both single arm studies (that only included COVID-19 patients), as well as comparative studies (comparing COVID-19 patients vs controls) were eligible for inclusion if reporting new diagnosis of IBS or FD according to Rome III or IV criteria17, 18 within a cohort of adult (more than 18 years old). The Rome III and IV criteria require at least 6 months since symptom onset and 3 months meeting the diagnostic criteria, but the 6 months duration criteria can be shortened when a clinician has evaluated the symptoms sufficiently and it is satisfied that other diagnoses are confidently excluded.19 Confirmed COVID-19 cases refer to the definitions according to the World Health Organization document released in March 2020,20 thus a confirmed COVID-19 case is a person with laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 infection, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms. In comparative studies, subjects/patients without a COVID-19 diagnosis were included as controls. Studies that only included COVID-19 patients with IBS or FD and case reports, were excluded. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or in which essential information was missing or cannot be obtained from the authors were also excluded.

2.1.2 Data collection process and quality assessment

Relevant data were independently extracted by two authors (GM and MM), using a standardised form. The following items were extracted from each study: year of publication, country, the study design, the study setting (outpatient or hospitalised COVID-19 patients and controls when available), the total number of patients, including age and gender of the participants, the total number of COVID-19 patients with and without FD and with or without IBS, the follow-up length in months, the Rome criteria used for DGBI diagnosis, the exclusion of patients with previous chronic gastrointestinal diseases or symptoms and, when available, the total number of controls with and without FD and with or without IBS. In case of multiple publications for a single study, the latest publication was considered and supplemented, if necessary, with data from the previous publications. The quality of selected studies was independently assessed by two investigators (MM and GM) using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.21 Overall, quality of studies was rated as Good, Fair or Poor. Discrepancies between reviewers concerning qualitative assessment were infrequent (overall inter-observer variation <10%), and disagreements were resolved through discussion and arbitration by a third reviewer (GB), when necessary.

2.2 Data analysis

The primary outcome was the pooled FD and IBS incidence rates. Rates of events were expressed as proportions for all studies and used to calculate pooled FD and IBS incidence rates. After data extraction, 95% confidence intervals (CI) of FD and IBS rates for each study were calculated using a random-effect model, using the method of DerSimonian and Laird, to provide a conservative estimate of the incidence of FD and IBS. Heterogeneity across the studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. In particular, the value of I2 describes the percentage of variability in point estimates which is due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error: for an I2 < 50%, the risk of heterogeneity between studies was ranked low-moderate, whereas for I2 ≥ 50%, the risk of heterogeneity was ranked high.22 Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by conducting subgroup analyses and reporting the test for heterogeneity between subgroups. In presence of at least 10 studies, to explore heterogeneity, the impact of confounding covariates (country, study design, study setting, length of follow-up, exclusion of patients with previous gastrointestinal disease and methodological quality of the studies included according to NIH) on the meta-analytic results was evaluated using meta-regression analysis,23 reporting β coefficient ± standard error (SE). Since a low number of studies have been found, the p values were also recalculated using Monte Carlo permutation24 with a number of permutations of 5000 in order to obtain sufficient precision.25 For FD, due to the low number of studies we conductedsensitivity analyses excluding only retrospective studies. For IBS, we conducted sensitivity analyses excluding retrospective studies and those without the exclusion of patients with previous chronic gastrointestinal diseases. Publication bias was investigated using the Egger test; a p < 0.05 indicated a significant small size study effect. For assessing the risk of IBS or FD among subjects with and without COVID-19, odds ratio (OR) was calculated for each individual study; afterwards, estimates were pooled, and 95% CI and p values were calculated. All analyses were carried out using STATA statistical software (Stata Corp).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study selection

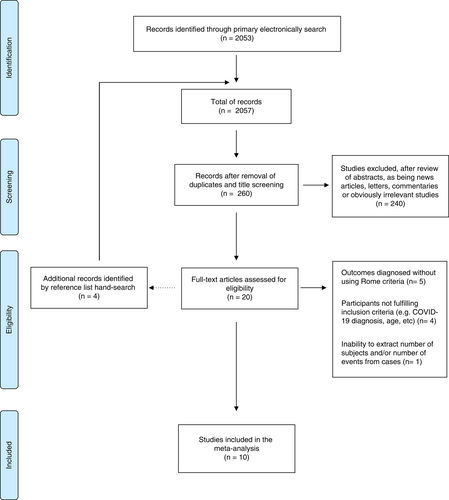

The electronic search identified a total of 2057 records; after title screening and duplicates removal, 260 articles were screened and finally 20 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). Of the 20 records selected, five studies were excluded for reporting FD or IBS without using Rome criteria,26-30 three for reporting FD or IBS rates without reporting COVID-19 diagnosis,31-33 one for reporting FD and IBS in children34 and one for inability to extract number of subjects and/or number of events from cases.35

Thus, a total of 10 studies,12-14, 36-42 all full texts, met the eligibility criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.

3.2 Study description

Table 1 resumes the main characteristics and the main outcomes of the 10 studies included in the meta-analysis. A total of 3998 patients were considered, of whom 2763 (69.1%) COVID-19 patients and 1235 (30.9%) controls. In all studies, COVID-19 testing was performed for the presence of symptoms, except one with testing performed within a routine public health surveillance programme.39 The rate of females included in the studies ranged from 27.1%14 to 70%.37 The median age of patients included ranged from 2914 to 68 years.42 Four studies were carried out in North America,36-39 three in Europe12, 13, 42 and three in the Middle East and Asia.14, 40, 41 Four studies had a retrospective design,13, 36-38 four studies a prospective design,12, 39-41 one study reported a prospective COVID-19 group and a retrospective control group14 and one study reported on prospectively assessed data on a retrospective cohort.42 Two studies reported that FD and/or IBS criteria were applied after a follow-up of <6 months,13, 40 five after a follow-up of 6 months14, 38, 39, 41, 42 and three after a follow-up of more than 6 months.12, 37, 38 Six studies reported of hospitalised COVID-19 patients,12, 14, 38, 40-42 three of hospitalised and/or outpatients COVID-19 subjects13, 36, 37 and one study did not report this data.39 Among studies reporting a control group, two compared outpatient or hospitalised COVID-19 with healthy controls,13, 40 one compared hospitalised COVID-19 with COVID-19-negative outpatients14 and one compared hospitalised COVID-19-positive versus -negative patients.12 All except two studies,36, 41 excluded patients with previous chronic gastrointestinal diseases, while only one study12 excluded patients with previous gastrointestinal symptoms.

| Study, year | Country | Age (years) COVID-19/controls | Sex (females, %) COVID-19/controls | Design | Setting COVID-19/controls | Follow-up (months) | COVID-19/controls n | FD in COVID-19/ controls n (%) | IBS in COVID-19/ controls n (%) | Rome criteria | Exclusion of patients with chronic GI disease | Exclusion of patients with previous GI symptoms | Overall NIH quality assessmenta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noviello D et al., 202113 | Italy | 44.1 (mean)/39.6 (mean) | 40.2%/ 60.7% | Internet-based survey | Outpatient and hospitalised/healthy controls | 4.8 ± 0.3 months | 164/183 | - | 43 (26%)/46 (25.1%) | Rome IV | Yes | No | Good |

| Blackett JW et al., 202236 | United States | 43 (median) | 67% | Internet-based survey | Outpatient (92.6%), hospitalised (7.4%) | 6 months | 749/0 | – | 13 (1.7%) | Rome IV | No | No | Fair |

| Nakhli et al., 202237 | United States | ≤65 years (79%) | 70% | Internet-based survey | Outpatient (60%), hospitalised (24%) | 6–9 months | 164/0 | 37 (22.6%) | 9 (5.5%) | Rome IV | Yes (IBS) | No | Fair |

| Blackett JW et al., 202238 | United States | <70 years (63.9%) | 49% | Internet-based survey | Hospitalised | At least 6 months | 112/0 | – | 44 (39%) | Rome IV | Yes (IBS) | No | Good |

| Ghoshal UC et al., 202214 | India/Bangladesh | 29–42 (median) | 27.1% | Prospective, retrospective (controls) | Hospitalised/outpatient | 6 months | 280/264 | 11 (4.2)/0 | 15 (5.3%)/1 (0.4%) | Rome IV (IBS)/Rome III FD | Yes (IBS) | No | Good |

| Austhof E et al., 202239 | United States | 42.7–45 (mean) | 66.3% | Prospective | – | 6 months | 49/0 | – | 5 (10.2%) | Rome IV | Yes | No | Good |

| Golla R et al., 202240 | India | 38.02 (mean)/ 37.94–38.47 (mean) | 49%/42.2% | Prospective | Hospitalised/healthy controls | 3 months | 320/600 | 8 (2.5%)/0 | 10 (3.1%)/0 | Rome IV | Yes | No | Good |

| Farsi F et al., 202241 | Iran | 38.41 (mean) | 58.4% | Prospective | Hospitalised, outpatient | 6 months | 233/0 | – | 27 (11.6%) | Rome IV | No | No | Good |

| Nazarewska A et al., 202242 | Poland | 68 (median) | 45.1% | Prospective questionnaire, retrospective cohort | Hospitalised | 6 months | 257/0 | – | 15 (5.8%) | Rome IV | Yes (IBS) | No | Fair |

| Marasco G et al., 202212 | Multicentre (Europe based) | 49.9 (mean)/50.9 (mean) | 40.1%/37.9% | Prospective | Hospitalised | 12 months | 435/188 | 16 (3.7%)/4 (2.1) | 14 (3.2%)/1 (0.5%) | Rome IV | Yes | Yes | Good |

- Abbreviations: COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; FD, functional dyspepsia; GI, gastrointestinal; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

- a The quality of selected studies was independently assessed by two investigators (MM and GM) using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.21 Overall quality of studies was rated as Good, Fair or Poor. Discrepancies between reviewers concerning qualitative assessment were infrequent (overall inter-observer variation <10%), and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Table 1 summarises the methodological quality evaluation of the studies included, which is detailed in Table S1. All the studies showed good or fair quality according to the NIH quality assessment scale.

3.3 Functional dyspepsia

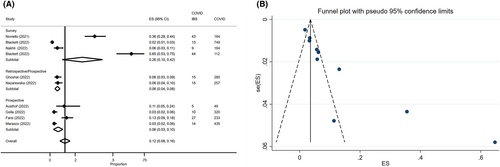

Among the four studies reporting the incidence of post-COVID-19 FD, 1199 COVID-19 patients were considered for the assessment of FD pooled incidence rate. Post-COVID FD was reported by 72 patients (4%, 95% CI: 3%–5%) without heterogeneity between studies (I2 0%) (Figure S1). Considering the three studies with a control group, a total of 2087 patients were included, of whom 1035 (49.6%) COVID-19 patients were compared to 1052 (50.4%) controls; FD was reported in 3% of COVID-19 patients (95% CI: 2%–4%) and 2% of controls (95% CI: 1%–5%). The pooled OR for FD development in COVID-19 patients compared to controls was 8.07 (95% CI: 0.84–77.87, p = 0.071) (Figure 2A), with substantial heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 67.9%).

3.4 Irritable bowel syndrome

Among the 10 studies reporting the incidence of post-COVID-19 IBS, 2763 COVID-19 patients were considered for the assessment of IBS pooled incidence rate. Post-COVID IBS was reported by 195 patients (12%, 95% CI: 8%–16%), with high heterogeneity (I2 95.6%) between studies; ‘small study effect’ was observed using the Egger test (p = 0.002) (Figure 3). Figure S2 reports IBS incidence in subgroup analysis according to different possible confounding covariates in order to explore heterogeneity between studies, such as study design (p = 0.06) country (p = 0.15), study setting (p = 0.02), length of follow-up (p = 0.09) and the exclusion of patients with previous chronic gastrointestinal diseases (p < 0.01). IBS rates were higher in retrospective studies, in studies from North America or reporting on hospitalised patients or with a follow-up >6 months or reporting results after the exclusion of patients with previous chronic gastrointestinal diseases. As example, considering only studies including a prospective COVID-19 cohort, the IBS incidence dropped down to 6% (95% CI: 3%–10%), but heterogeneity remained high (I2 83.8%) (Figure 3). However, meta-regression analysis (Table 2) showed that overall estimates on post-COVID-19 IBS incidence was not affected by the study design, geographic origin, patient's setting, length of follow-up, the exclusion of patients with previous chronic gastrointestinal diseases or the study quality according to the NIH quality assessment scale. As part of sensitivity analyses, according to the test of heterogeneity in subgroup analysis, we excluded studies reporting retrospective COVID-19 cohorts and those reporting results without excluding patients with previous gastrointestinal diseases,13, 36-38, 41 finding a pooled IBS incidence rate of 4% (95% CI: 3%–6%), with a low-moderate heterogeneity (I2 41.9%) between studies (Figure S3). Functional dyspepsia and IBS incidences at different time points, after excluding studies with retrospective COVID-19 cohorts, are reported in Figure S4.

| Covariates | Number of studies | Beta coefficient ± SE | Adjusted R2 (%) | p value | p value ± SE after Monte Carlo permutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country (North America vs Europe vs Middle East/Asia) | 10 | 0.938 (±0.071) | −4.49% | 0.424 | 0.486 (0.007) |

| Study design (survey vs retrospective/prospective vs prospective) | 10 | 0.894 (±0.070) | 10.08% | 0.191 | 0.221 (0.006) |

| Study setting (outpatient vs hospitalised vs mixed) | 10 | 1.034 (±0.080) | −11.11% | 0.678 | 0.655 (0.007) |

| Length of follow-up (<6 vs 6 vs >6 months) | 10 | 1.038 (±0.097) | −11.95% | 0.703 | 0.825 (0.005) |

| Exclusion of patients with previous gastrointestinal disease (no vs yes) | 10 | 1.095 (±0.176) | −9.59% | 0.588 | 0.728 (0.006) |

| NIH (fair vs good) | 10 | 1.154 (±0.154) | 1.50% | 0.311 | 0.278 (0.006) |

- Abbreviations: NIH, National Institutes of Health; R2, relative reduction in between-study variance: the value indicates the proportion of between study variance explained by covariate; SE, standard error.

Considering the four studies with a control group,12-14, 40 a total of 2434 patients were considered, of whom 1199 (49.3%) COVID-19 patients were compared to 1235 (50.7%) controls; IBS was reported in 9% of COVID-19 patients (95% CI: 4%–15%) and 7% of controls (95% CI: 2%–11%). The pooled OR for IBS development in COVID-19 patients compared to controls was 6.27 (95% CI: 0.88–44.76, p = 0.067), with high heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 81.4%) (Figure S5). After excluding the only retrospective study included in this sub-analysis,13 the pooled OR for IBS development in COVID-19 patients compared to controls was 12.92 (95% CI: 3.58–46.60, p < 0.001) (Figure 2B), without heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 0%).

4 DISCUSSION

Recent evidence showed that several persistent symptoms can last after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.5 This condition is now termed long COVID, and includes multisystemic symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnoea, cardiovascular symptoms, cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, muscle pain, concentration problems and headache.5 However, the long COVID-19 clinical spectrum has yet to be completely defined due to continuous updates. Moreover, several authors recently reported persistent gastrointestinal symptoms after COVID-19, which have been included in the long COVID-19 definition.43 This systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data from 10 studies assessing the rate of IBS and FD in COVID-19 patients, showed an overall IBS rate of 12%, which dropped down to 4% in high quality studies, and an overall FD rate of 4%. COVID-19 patients had a significant higher probability of developing IBS in prospective studies, with a pooled OR compared with controls of 12.9 according to three studies. The probability of developing FD was higher for COVID-19 compared with controls, although without statistical significance. Our analysis also suggests that the incidence of post-COVID-19 IBS was not significantly influenced by the study design (retrospective vs. prospective), geographic origin, patient's setting (hospitalised vs outpatients), length of follow-up, the exclusion of patients with a previous diagnosis of gastrointestinal disease or the study quality according to the NIH quality assessment scale.

The development of DGBI after an infection has been widely reported by several authors and by a meta-analysis.44 In particular, IBS incidence was increased after a bout of acute gastroenteritis following infection with bacterial, parasitic/protozoa or viral pathogens.11 However, few studies have evaluated the incidence of these syndromes following viral infection. Therefore, the evaluation of long-term gastrointestinal symptoms reported by COVID-19 survivors resembling PI-DGBI, represented a unique opportunity to further explore this field.10 SARS-CoV-2 infection is able to trigger the development of gastrointestinal symptoms during the acute phase of infection,9 through direct cellular damage, inflammation, gut dysbiosis, enteric nervous system dysfunction and a pro-thrombosis state induced by the virus.7, 9, 45 These pathophysiological mechanisms have also been partially found in COVID-19 survivors reporting persistent intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms, such as gut microbiota modifications, gut dysmotility, increased intestinal permeability and modifications of enteroendocrine cell function and serotonin metabolism.11, 46 Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids have been found in the small bowel of COVID-19 survivors after the acute infection, together with persistent aberrant immunological activation.47, 48 Therefore, the pathophysiological process underlying long gastrointestinal COVID-19 are similar to those found in other PI-DGBI,11 additionally pointing out their biological plausibility.12

To date, only one preliminary pooled data analysis tried to assess the frequencies of IBS (four studies) and FD (three studies) after COVID-19, although without using the Rome IV criteria for PI-DGBI diagnosis, or without reporting results after the exclusion of patients with previous gastrointestinal disease or compared to a control group.43 Nevertheless, in this study, the authors reported a frequency of 20% for dyspepsia and of 17% for IBS after COVID-19, with only two and one study reported the frequency of dyspepsia and IBS among patients with long COVID-19 respectively.43 The small number of studies included, and the mentioned biases may explain the discrepancies between our results and those by Choudhury et al,43 which may have overestimated the frequencies of IBS and FD after COVID-19. On the other hand, our results are in line with those of the metanalysis by Klem et al,44 that reported an overall prevalence of PI-IBS after a viral infection of 6.4%. However, the authors reported a great variability when examining rates within and beyond 12 months of follow-up after the acute bout of viral infection, accounting for 19.4% and 4.4% respectively.44 On this line, the only study included in our meta-analysis with a follow-up of 12 months12 reported an IBS incidence of 3.2% in COVID-19 patients.

Similar to the study by Klem et al,44 we found that the most common IBS subtype reported after COVID-19 was IBS with diarrhoea, ranging from 34.7% in the study by Austhof et al39 to 60% in the study by Ghoshal et al.14 Unfortunately, we were unable to assess predictive factors for post-COVID-19 IBS incidence since only three studies12, 14, 41 reported this association. However, all predictive factors reported had a biological plausibility,11 including increased levels of anxiety and depression,41 the severity of the acute COVID-19 infection,12, 14 the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms during the acute COVID-19 infection,14 history of allergies and chronic PPI intake.12

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis aimed at assessing the pooled rate and the OR of IBS and FD after COVID-19. Our meta-analysis has several strengths, such as the comprehensive literature search which minimises the risk of missing studies, and the inclusion of a large cohort of patients from different countries allowing to generalise the validity of our results worldwide. Furthermore, all studies included had a fair or good quality according to the NIH scale. As additional strength of our analysis, we performed a meta-regression analysis for finding sources of heterogeneity. Finally, another strength of our meta-analysis is the subgroup analysis which allowed to perform additional evaluations after removing retrospective studies and those without the exclusion of patients with previous gastrointestinal disease, which may have potentially biased our results.

At the same time, this meta-analysis has some weaknesses. We included also retrospective studies, which were all Internet-based surveys, therefore suffering from several biases, that is, recall bias. Moreover, we considered studies reporting COVID-19 patients from different setting (e.g. hospitalised, outpatients, etc.) and different lengths of follow-up, thus with different degree of COVID-19 clinical course and different observation periods that may have influenced the pooled estimates of post-COVID-19 DGBI. Indeed, according to the study by Klem et al44 and that by Marasco et al,12 the severity of the acute viral infection was related to the risk of developing post-COVID-19 IBS. Nevertheless, we were unable to find associations between incidence of FD and IBS and various methodological and demographic features at meta-regression, probably due to an underpowered analysis due to type II error. Moreover, we were unable to analyse data regarding the correlation between post-COVID-19 FD and IBS incidence and SARS-CoV-2 viral variants and any vaccination performed. Finally, in our meta-analysis, it was not possible to consider other confounding factors affecting IBS incidence such as psychological and other somatic co-morbidities, previous and in-hospital treatments, etc. Moreover, our data mainly report of hospitalised COVID-19 patients and should be interpreted in the light of the changing hospitalisation rates for COVID-19 over time.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence that patients with COVID-19 present a higher risk of developing IBS compared to non-infected subjects. Our data should be carefully considered by clinicians when managing patients with long COVID-19 symptoms to properly and timely recognise IBS occurrence. However, due to the high prevalence of COVID-19 at the global level, our data also support the increased burden to the healthcare system due to newly diagnosed post-COVID-19 IBS. Our data should be further explored in correlation to each SARS-CoV-2 variants and to the protective effect of anti-COVID-19 vaccines,49, 50 which may be associated to less severe COVID-19 and therefore to a reduced risk of long COVID-19.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

GM and GB designed the systematic review and meta-analysis; GM, MM, CC, MRB performed the literature search, study selection and data extraction; GM performed statistical analyses; GM and MM drafted the paper; all authors critically reviewed the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal interests: We thank Dr. Laura Chierico (Medical Librarian). Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was supported in part by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research and funds from the University of Bologna (RFO) to G.B. G.B. is a recipient of an educational grant from Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna, and Fondazione Carisbo, Bologna, Italy. GB is a recipient of the European grant HORIZON 2020-SC1-BHC-2018-2020/H2020-SC1-2019-Two-Stage-RTD-DISCOVERIE PROJECT. M.R.B. is a recipient of a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata GR-2018-12367062). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

We declare no competing interests.

PERSONAL AND FUNDING INTERESTS

None.